Abstract

Objectives

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in widespread morbidity and mortality with the consequences expected to be felt for many years. Significant variation exists in the care even of similar patients with COVID-19, including treatment practices within and between institutions. Outcome measures vary among clinical trials on the same therapies. Understanding which therapies are of most value is not possible unless consensus can be reached on which outcomes are most important to measure. Furthermore, consensus on the most important outcomes may enable patients to monitor and track their care, and may help providers to improve the care they offer through quality improvement. To develop a standardised minimum set of outcomes for clinical care, the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) assembled a working group (WG) of 28 volunteers, including health professionals, patients and patient representatives.

Design

A list of outcomes important to patients and professionals was generated from a systematic review of the published literature using the MEDLINE database, from review of outcomes being measured in ongoing clinical trials, from a survey distributed to patients and patient networks, and from previously published ICHOM standard sets in other disease areas. Using an online-modified Delphi process, the WG selected outcomes of greatest importance.

Results

The outcomes considered by the WG to be most important were selected and categorised into five domains: (1) functional status and quality of life, (2) mental functioning, (3) social functioning, (4) clinical outcomes and (5) symptoms. The WG identified demographic and clinical variables for use as case-mix risk adjusters. These included baseline demographics, clinical factors and treatment-related factors.

Conclusion

Implementation of these consensus recommendations could help institutions to monitor, compare and improve the quality and delivery of care to patients with COVID-19. Their consistent definition and collection could also broaden the implementation of more patient-centric clinical outcomes research.

Keywords: COVID-19, quality in healthcare, international health services

Strengths and limitations of this study.

These consensus recommendations were generated by a large international working group consisting of all relevant stakeholders with an interest in outcomes of care for patients with COVID-19.

The diversity of the working group means that the recommendations included in the standard set are applicable to all settings.

The methodology employed in the generation of the standard set meant that the focus was on outcomes of relevance to patients throughout and there is a deliberate emphasis on the use of patient-reported outcome measures in the set.

SARS-CoV-2 was discovered just over 1 year ago and so we cannot yet be certain about the long-term outcomes of the disease.

ICHOM (International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement) standard sets typically undergo an open review process prior to publication, in which the draft set is distributed to patients and their representative groups for feedback; however, this was not possible for this project given the timeframe.

Introduction

SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic, has infected almost 250 million people and resulted in the deaths of over 5 million.1 Although knowledge about the acute illness has rapidly expanded, there is increasing evidence that COVID-19 may have long-term sequelae, with adverse health outcomes and poor health-related quality of life lasting far longer than the acute disease.2

Significant variation exists in the care even of similar patients with COVID-19, including treatment practices within and between institutions and countries.3 Furthermore, outcome measures vary among the largest clinical trials on the same therapies.4 Understanding which therapies are of most value will remain a challenge unless consensus can be reached on which outcomes are most important to patients to measure. While survival or indirect measures of patient’s health status, for example, hospitalisation, the need for mechanical or non-invasive ventilation, as well as measures of resource utilisation, are frequently recorded in trials, direct measures of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are rarely measured and/or recorded.5 Furthermore, the follow-up period of many trials is insufficient to detect some outcomes affecting patients long after hospital discharge. There is, therefore, a need for a standardised approach to outcome measurement in COVID-19 to inform clinical practice and real-world therapeutic research and to allow healthcare providers to monitor outcomes and to identify areas for quality improvement. A standard set of outcomes, that is, standardised outcomes, measurement tools and time points and risk adjustment factors for COVID-19,6 could help benchmark best practice across institutions, facilitating improvements in care during future outbreaks and providing value in healthcare. It could also standardise approaches to global research for patient benefit.

To support the development of a standardised outcome set in COVID-19 for integration into clinical practice (and to inform clinical research), the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) convened an international multidisciplinary Working Group (WG) of experts and patient representatives. As a not-for-profit organisation, ICHOM has developed 38 standard sets of value-based outcomes for use in routine clinical practice in a range of medical conditions, such as coronary artery disease, stroke and cancer.7 Over 600 organisations have implemented ICHOM sets including 15 national registries. Standard sets are reviewed and updated annually by ICHOM.

The aim of this paper is to present a standardised minimum set of outcomes for COVID-19, focusing on the inclusion of PROs, and case-mix variables, for comparisons across treatment modalities and institutions.

Methods

Composition of the WG (including patient and public involvement)

WG members were identified through several avenues. A rapid review was conducted by the project team in the project initiation phase to identify relevant patient organisations, measurement initiatives, professional bodies and publications actively addressing questions relating to outcome measurement for COVID-19 with a particular focus on patient-centred outcomes. Relevant organisations were contacted and information about the role of WG members shared both directly as well as through social media channels. Open recruitment calls were then held inviting interested individuals to participate in the WG. A matrix of candidates was composed to facilitate the representation of diverse geographies, disciplines, types of expertise, and a balance of specialist interests, for example, infectious diseases, respiratory disease, mental health, primary care, intensive care. A shortlist was created that would represent different matrix cells, and ICHOM subsequently invited shortlisted individuals to participate. In addition, individuals or organisations were given the opportunity to recommend additional candidates for consideration by the ICHOM project team.

Development of the COVID-19 standard set

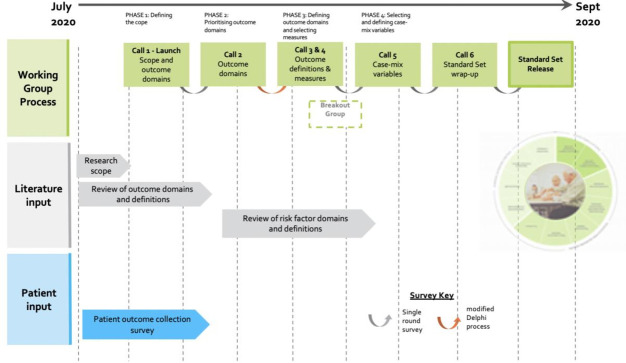

The WG convened during six teleconferences between July 2020 and September 2020, following a structured process similar to that of previous ICHOM WGs. The development of the standard set involved four phases, as illustrated in figure 1: defining the scope of the project; prioritising outcome domains; defining outcome domains; and evaluating and selecting outcome measures that would be used to measure these domains, including clinical data and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs); and selecting and defining case-mix variables.

Figure 1.

Timeline and data collection process.

Identification of potential outcomes, outcome measures and case-mix variables

The MEDLINE database was used to search for relevant publications from which potential outcome domains, outcome measures, PROMs and case-mix variables were extracted in order to generate a long-list for the WG to consider. The search strategy used for the MEDLINE search was:

((‘COVID-19’[Title]) OR (‘novel coronavirus’[Title])) AND (‘Outcome’[Title]).

Two members of the project team (WHS and NS) carried out the MEDLINE search using the above strategy on 1 July 2020, and included papers published in English language between 1 December 2019 and 1 July 2020.

Outcomes measured in published trials (apart from reviews which were excluded in order to generate a list of primary outcomes from trials) were extracted as well as outcomes being measured in ongoing trials, as identified by the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) database.8 Studies involving specific populations, such as gender, ethnicity, as well as interventions targeting specific clinical outcomes, for example, resolution of fever, and laboratory-based outcome measures such as inflammatory markers were excluded as these were deemed by the WG to represent process measures rather than outcomes that in and of themselves mattered directly to patients. In addition to extracting the outcomes, the outcome measures used to measure these outcomes in the trials included were also extracted. These outcome measures were discussed after the outcomes themselves had been selected.

In addition, an electronic survey was distributed at the start of the project to patients and patient representatives, through WG members’ healthcare institutions, in line with their ethical guidelines (see online supplemental file 1). It was also distributed through the ICHOM newsletter and social media platforms, as well as to the European Heart Network and European Lung Foundation patient fora, in order to identify any additional outcomes that were of particular importance to patients. Finally, outcomes were extracted from previously published ICHOM standard sets that were of potential relevance to patients with COVID-19, for example, patient-reported measures such as health-related quality of life, and clinical outcomes such as survival.

bmjopen-2021-051065supp001.pdf (1MB, pdf)

Consensus process

WG teleconferences were held every 2 weeks. Following each teleconference, the project team circulated an electronic survey via the Qualtrics platform to the WG to gather feedback on each key decision. An online modified Delphi process was performed over three rounds for the selection of outcomes, following the RAND/University of California (Los Angeles) methodology9 and based on a literature review,10 to achieve consensus on which outcomes should be included. Inclusion in the standard set required that at least 80% of the WG voted an item as ‘essential’ (score 7–9 on a 9-point Likert scale) in each voting round. WG members were given 1 week to complete each survey. Outcomes were excluded if at least 80% of the WG voted an item as ‘not recommended’ (score 1–3). Inconclusive domains were discussed and revised and put to a second round of voting. Outcomes that still had not garnered the required consensus for inclusion were put to a final third round vote. These three rounds were completed prior to considering the selection of outcome measures to capture the outcomes, which did not use the same Delphi methodology.

Selection of PROMs and case-mix variables

After PROs were chosen for inclusion in the standard set, corresponding measures were identified from the literature, from tools previously used in other ICHOM standard sets for similar outcome domains, and by outcome experts in the WG. The original and validation studies of the instruments were examined in order to evaluate the psychometric quality, domain coverage, and feasibility of measurement and implementation. A breakout group consisting of academics and clinicians with particular expertise in PRO measures convened to decide on the most appropriate measures to use.

A different consensus-gathering process, this time requiring 70% consensus from the WG for each item, was used to agree on which measures and case-mix variables should be recommended in line with the methodology used in all ICHOM standard sets for this part of the study, as well as the time points for measuring each outcome. The 70% consensus level is thought to be sufficient for the selection of outcome measures and case-mix variables, whereas a more stringent threshold of 80% or more of the WG voting an outcome as ‘essential to include’ on the Likert scale is required in ICHOM methodology for the selection of the outcomes themselves. The results of each vote were reviewed by the WG at the subsequent teleconference. The criteria by which outcome domains were assessed for inclusion in the set were in accordance with the concepts of value-based healthcare as described by Porter.11 Variables to be used as case-mix factors were assessed on: (1) relevance, (2) independence and (3) measurement feasibility.

Results

Working Group

ICHOM established a geographically diverse WG covering a broad range of specialties relevant to COVID-19. The WG consisted of 28 members, including clinicians, epidemiologists, research scientists, and patients and patient advocates/representatives from 13 countries across North and South America, Europe, Africa, the Middle East, South Asia and Australia (table 1). A project team (WS, LF, NS, CN and KB) guided the efforts of the WG.

Table 1.

Summary of ICHOM C19 standard set of outcomes

| Outcome domain | Outcome subdomains | Definition | Outcome measure |

| Functional status and quality of life | Health-related quality of life | The perceived quality of an individual’s daily life, assessing their health and well-being or lack thereof. A multidimensional concept that includes domains related to physical, mental, emotional and social functioning. | PROMIS Global Health 1.2 |

| General physical functioning | An individual’s ability to perform and/or participate in usual daily activities required to meet essential needs, fulfil usual roles, meet usual responsibilities, and maintain health and well-being. | PROMIS Global Health 1.2 | |

| Vitality/energy | Capacity for work and leisure activities, and efficiency of accomplishment related to a feeling of weariness or tiredness. | FLU-PRO | |

| Mental functioning | Mental health symptoms and emotional well-being | An individual’s emotional, psychological and social well-being, including negative feelings and fears, as well as moderate to high levels of anxiety or psychological distress. | PROMIS Global Health 1.2 |

| Cognitive status | An individual’s mental process of knowing, including awareness, perception, reasoning and judgement. | Clinician measures | |

| Social functioning | Feelings of loneliness and isolation | An individual’s negative feelings related to the perception of being alone, disconnected or isolated. | PROMIS Social Isolation 4 a |

| Productivity | An individual’s ability to carry out tasks, actions or participate in life situations. | PROMIS Global Health 1.2 | |

| Clinical outcomes | Survival | Any cause of death in a patient with COVID-19. | Clinician measures |

| Meeting criteria for critical care admission | Patients whose medical needs cannot be met through standard ward-based care in an acute hospital, who would meet criteria for a high dependency or critical care unit. Patients who meet criteria for critical care admission may not in fact be admitted to critical care facilities for other reasons, eg, resource constraints, however, should be included under this definition. | Clinician measures | |

| Disease course severity | Mild: No need for hospitalisation Moderate: Hospitalisation without need for non-invasive or mechanical ventilation Severe: Received non-invasive and/or mechanical ventilation, or died; admission to High Dependency Unit (HDU) or Intensive Care Unit (ICU). |

Clinician measures FLU-PRO |

|

| Persisting organ damage | End-organ damage, including the central or peripheral nervous system, as a result of the COVID-19 infection that results in impaired function in the individual. | Clinician measures | |

| Duration of hospitalisation | Number of nights spent in hospital being treated for symptoms related to COVID-19 (irrespective of whether COVID-19 was the reason for admission or if the patient developed COVID-19 while in hospital for another reason). This includes nights spent in hospital on subsequent hospital admissions during the follow-up period if the individual being readmitted was being treated for symptoms related to COVID-19 on that admission. | Clinician measures | |

| Symptoms | Symptoms | A subjective perception suggesting bodily impairment or malfunction, affecting the individual in a negative manner. | FLU-PRO |

ICHOM, International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement; PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System.

Scope

The outcomes and measures included in the COVID-19 standard set were defined for a target population of all adults over the age of 18 years with confirmed or highly suspected SARS-CoV-2 infection, as defined by WHO,12 in primary, secondary or tertiary care settings. Children under the age of 18 years, as well as asymptomatic individuals with positive diagnostic tests, were excluded from the set. Different geographical and resource contexts were considered so that the standard set can be applied globally.

Outcomes

About 86%, 89% and 82% of WG members participated in the first, second and third rounds of the modified Delphi process, respectively. Out of 64 possible outcomes (see online supplemental file 2) for a list of the sources of preliminary outcomes) identified through the methodology as described, the WG selected 13 outcomes. There was significant overlap between the outcomes identified from the different sources, and during the WG teleconferences, decisions were taken to merge or rename outcomes. The Reference Guide containing the definitions of all outcome domains included, as agreed by the WG, is published on the ICHOM website at wwwichomorg. The outcomes were categorised into five major groups: functional status and quality of life, clinical outcomes, mental functioning, social functioning and symptoms. The set of outcomes and measures that were selected are detailed in table 1.

bmjopen-2021-051065supp002.pdf (40.5KB, pdf)

Each domain has a number of subdomains to capture what is important to patients. The domain on clinical outcomes is to be assessed by clinicians. For each of the remaining domains, the WG identified an appropriate outcome measure to use. Considering the overlap among measures, the WG identified the following measures: Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Global 1.2,13 PROMIS Social Isolation 4a14 and FLU-PRO.15

Baseline characteristics and case-mix variables

In addition to the outcomes and outcome measures, the WG selected important baseline health characteristics to enable comparison between providers (table 2). These baseline health characteristics include demographic factors, for example, age, sex, race, ethnicity, level of education, clinical factors, for example, comorbidities and body mass index, and treatment-related factors, for example, need for ventilation, type of ventilation, duration of ventilation, duration of critical care admission.

Table 2.

Summary of COVID-19 standard set case-mix variables

| Case-mix category | Variable | Measure | Timing | Data source |

| Demographic factors | Age | Year of birth. | Baseline | Patient record |

| Sex | The patient’s sex at birth. | |||

| Race | The biological race of the patient. | Patient record | ||

| Ethnicity | The cultural ethnicity of the patient that they most closely identify with. | |||

| Level of education | Highest level of education completed based on local standard definitions of education levels. | Patient record | ||

| Clinical factors | Comorbidities | Prior and current diagnosis of disease or no presence of diagnosis. | Baseline | Patient/clinician |

| Body mass index | Height and weight are used to calculate BMI. | Clinician/healthcare provider | ||

| Treatment- related factors |

Need for ventilation | Did the patient require any ventilation during their hospital admission? | Baseline/ updated monthly | Clinician/healthcare provider |

| Type of ventilation | What type of ventilation was administered? | |||

| Duration of ventilation | How long did the patient require ventilation? | |||

| Duration of critical care admission | How long was the patient’s initial stay in critical care? |

BMI, body mass index.

Timeline for follow-up

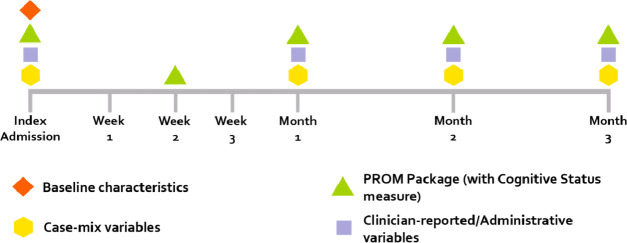

The WG decided to track patient outcomes over a 3-month period following the diagnosis or following criteria being met for highly suspected SARS-CoV-2 infection (figure 2). The outcome collection period can be extended for a further 3 months if the patient has not yet fully recovered. The WG delegated to the treating physicians the decision whether or not to extend data collection.

Figure 2.

Follow-up timeline and data collection guidance. PROM, patient-reported outcome measure.

Discussion

In this project, an international WG developed a consensus set of the most important outcomes and outcome measures in COVID-19. By measuring and reporting the same outcomes, and adjusting for the case-mix variables, providers may be able to improve the quality of care offered to patients by learning from other institutions using the same standard set. The standard set could also benefit patients directly by allowing them to track their progress over time and seek care when appropriate through heightened awareness of symptoms that they may not necessarily realise are problems, for example, mental health symptoms, or waning productivity. The standard set could also be considered for use in future respiratory viral pandemics.

This is the first global effort to develop a standardised minimum set of patient-centred outcomes in COVID-19 for use in clinical practice. While we cannot yet be certain about the long-term outcomes of the disease, this work provides a starting point and there is scope for additional measures to be included as our understanding of the disease improves. Other groups, including the WHO Clinical Characterisation and Management Working Group, have sought to define sets of standardised outcomes in COVID-19. This group published a core outcome set primarily for research use. As such, the outcomes recommended by that group have a clinical and technical focus and include many indirect measures of patient outcomes.16 Our project focused on clinical practice, however, could also be used to inform real-world clinical research by incorporating direct patient outcomes, both in evaluating the course of illness and the effects of therapeutics. This standard set is patient-centric, using PROs as a key component of the set, and focusing primarily on outcomes that matter to patients, for example, an individual’s ability to perform and/or participate in usual daily activities rather than on clinical metrics.

The predominant use of indirect outcomes in clinical trials of COVID-19 and in monitoring patients’ progress with the disease runs the risk of missing issues of equal or more significance to those suffering with the illness— the disease burden of symptoms and impaired function that may persist long after the acute illness. While measuring survival and clinician-reported outcomes like hospitalisations is essential, it is equally important to measure PROs which add valuable information in those who do survive or who are discharged/remain in hospital. PROs can be used for long-term follow-up to assess the effect of the disease on a patient’s quality of life, and to alert treating physicians to the development of complications.17 There is an increasing body of literature suggesting benefit to patients of various drugs and vaccines against COVID-19. Validated, standardised PROs that comprehensively assess the symptom experience and patient function in COVID-19 across multiple domains could also facilitate meta-analyses and more precise estimates of treatment effects.

When considering which PRO measures to use in the set to measure overall quality of life, the WG felt that a generic as well as respiratory-specific measure would be most appropriate given the multisystem nature of COVID-19. One such universal measurement system is the PROMIS. The PROMIS Global Health (V.1.2) instrument, which is freely available, consists of ten global health items that represent five core PROMIS domains (physical function, pain, fatigue, emotional distress, social health).18 The majority of PRO measures included in this set that are not symptoms are covered within the PROMIS Global Health questionnaire. One outcome that the WG felt important to include which is not adequately covered in this instrument is loneliness/isolation, which is captured via the short PROMIS Social Isolation 4a tool.

In addition to the PROs included in the set, there are a number of clinical outcomes that the WG felt it essential to include. The WG felt it important to ensure that the direct endpoints used took account of the varying practices and resources that exist across the world. As such, the standard set is suitable for any primary, secondary or tertiary care setting in any country. Of note, while many COVID-19 studies report Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admission as an outcome, the WG took the view that because ICU provision and therefore the thresholds for admission to ICU vary so significantly depending on the context in which one practices, a more appropriate outcome measure would be ‘meeting criteria for ICU admission’ rather than admission itself that is, explaining the reason for ICU admission and not solely the event. A similar approach was taken when considering the issue of non-invasive ventilation, the use of which varied from being widespread to prohibited based on factors such as availability of oxygen and concerns around staff infection. The WG considered that ‘need for non-invasive ventilation,’ while important, could not be classed as an outcome since the criteria determining ‘need’ varied too much. Instead, this is included as a case-mix factor so that it can be controlled for in analyses.

The presence or absence of symptoms was included in the set on the basis that persistence of symptoms, for example, as part of ‘long COVID-19’, may be modifiable and may represent a significant disease burden. The WG elected to use a symptom scale that has been developed and validated for comprehensively measuring symptoms in viral respiratory tract diseases—the FLU-PRO scale.15 The scale was developed with patient input and its psychometric properties have been evaluated in a study with over 500 patients including those with influenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, enterovirus, rhinovirus, adenovirus and endemic coronaviruses and is being used currently in studies of COVID-19.19–21 The scale was adapted during COVID-19, but in general, can be used to measure symptoms in any viral respiratory illness.

Consideration was given during WG discussions as to the appropriate timeline of data collection for patient symptoms. Although the FLU-PRO asks patients about symptoms in the previous 24 hours, the WG felt it infeasible to ask patients to rate their symptoms daily for the entire course of the 3-month follow-up period. The WG’s recommendation for practical use was to ask patients to complete the FLU-PRO fortnightly for the first month and then monthly thereafter, in line with the timeline for collection of other PRO measures as part of the ‘PROM package’ depicted in the timeline in figure 2.

An important aspect of this project is the standardisation of outcome measurement in COVID-19 across differing regions and healthcare systems. To achieve this, we have published a comprehensive reference guide summarising the set, outcome reporting tools, adjustment variables and collection time points which is freely available at wwwichomorg.

Our approach does have some limitations. The standard set methodology is reliant on the composition of the WG. Although the WG recruited as diverse members as was possible given the time constraints, it is possible that a different WG would have come to different conclusions. Our methodology is reliant on the continued involvement of WG members over several months, and although we did not experience significant attrition during the various stages of the consensus-gathering process, nevertheless there remains the potential for attrition bias to have affected the results of the rounds of voting. Further, ICHOM standard sets typically undergo an open review process prior to publication in which the draft set is distributed to patients and their representative groups for feedback. Unfortunately, this was not possible within the timeframe of this project. The standard set was developed not as a static document but firmly with implementation in mind. As such, feasibility of measuring outcomes was a key concern during the outcome selection stage and therefore not all outcomes could be included in the set, despite being recognised by some members of the WG as important. Furthermore, feasibility of measuring and global adoption of the set were important determinants of the symptom scales and PROs that were selected by the WG.

The next stage of this project is to promote implementation of the standard set. Issues to overcome when considering implementing the COVID-19 set include: (1) budget; (2) availability of clinical leaders to champion the set and promote its adoption given pressing clinical commitments to direct patient care in the ongoing pandemic; (3) ensuring efficient and intuitive means of collecting and storing clinical data; and (4) ensuring consistent and accurate collection of PROs. Implementation of the set involves several phases as described previously.22

Conclusion

We have developed a consensus recommendation for a standardised minimum set of outcomes that our WG considered most important to patients with COVID-19 comprising functional status and quality of life, clinical outcomes, mental functioning, social functioning and symptoms. The use of PROs is central to the set and makes the recommendations particularly relevant. This standard set is targeted for integration into routine clinical practice and research. Use of the set may enable institutions to monitor, compare, and most importantly improve the quality of the care they deliver for patients with COVID-19 as the pandemic unfolds.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and members of the public were involved at the centre of the work described in this manuscript. Patients were at the heart of the WG that produced the standard set, and patients (and their representatives at patient organisations) were directly asked which outcomes they felt were most important for them at the start of the project. Most of these outcomes are included in the final list of outcomes selected by the WG. The patient members of the WG contributed to the review and final drafts of this manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @Anzarfarhala, @anmari_russell

Contributors: The project was conceived by the ICHOM Project Team – LF, NS, CN and WHS. The WG was chaired by KB who provided oversight to the Project Team throughout. All other authors listed in the manuscript met the authorship requirement criteria through consistent engagement in WG teleconferences, voting in the Delphi consensus process, and reviewing drafts of the manuscript. WHS acts as the guarantor.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Data are available upon reasonable request. These include complete survey results as well as results of the consensus-gathering processes described within the manuscript.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . WHO coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard. Available: https://covid19.who.int/

- 2.Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F, et al. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA 2020;324:603–5. 10.1001/jama.2020.12603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azoulay E, de Waele J, Ferrer R, et al. International variation in the management of severe COVID-19 patients. Crit Care 2020;24:486. 10.1186/s13054-020-03194-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qiu R, Wei X, Zhao M. Outcome reporting from protocols of clinical trials of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong AW, Shah AS, Johnston JC, et al. Patient-Reported outcome measures after COVID-19: a prospective cohort study. Eur Respir J 2020;56:2003276. 10.1183/13993003.03276-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ICHOM standard sets. Available: https://www.ichom.org/healthcare-standardization/#:~:text=ICHOM%20Standard%20Sets%20are%20standardized,matters%20most%20to%20the%20patient [Accessed 29 Dec 2020].

- 7.ICHOM. Available: https://wwwichomorg/standard-sets/#standard-sets [Accessed 29 Dec 2020].

- 8.WHO . International clinical trials registry platform (ICTRP). Available: www.who.int/clinical-trials-registry-platform

- 9.Fitch K. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method User’s Manual. Santa Monica, CA: Rand, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boulkedid R, Abdoul H, Loustau M, et al. Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: a systematic review. PLoS One 2011;6:e20476. 10.1371/journal.pone.0020476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Porter ME. What is value in health care? N Engl J Med 2010;363:2477–81. 10.1056/NEJMp1011024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO . COVID-19: case definitions, 2020. Available: file:///Users/williamseligman/Downloads/WHO-2019-nCoV-Surveillance_Case_Definition-2020.1-eng.pdf [Accessed 23 Nov 2020].

- 13.Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, et al. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res 2009;18:873–80. 10.1007/s11136-009-9496-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.A brief guide to the PROMIS social isolation instruments. outcomes measurement information system, 2015. Available: http://wwwhealthmeasuresnet/administrator/components/com_instruments/uploads/15-09-01_16-44-48_PROMISSocialIsolationScoringManualpdf [Accessed 29 December 2020].

- 15.Powers JH, Guerrero ML, Leidy NK, et al. Development of the Flu-PRO: a patient-reported outcome (pro) instrument to evaluate symptoms of influenza. BMC Infect Dis 2016;16:1. 10.1186/s12879-015-1330-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.WHO Working Group on the Clinical Characterisation and Management of COVID-19 infection . A minimal common outcome measure set for COVID-19 clinical research. Lancet Infect Dis 2020;20:e192–7. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30483-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aiyegbusi OL, Calvert MJ. Patient-Reported outcomes: central to the management of COVID-19. Lancet 2020;396:531. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31724-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, et al. The patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS): progress of an NIH roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med Care 2007;45:S3–11. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000258615.42478.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Powers JH, Bacci ED, Guerrero ML, et al. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of influenza patient-reported outcome (FLU-PRO©) scores in Influenza-Positive patients. Value Health 2018;21:210–8. 10.1016/j.jval.2017.04.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu J, Powers JH, Vallo D, et al. Evaluation of efficacy endpoints for a phase IIb study of a respiratory syncytial virus vaccine in older adults using patient-reported outcomes with laboratory confirmation. Value Health 2020;23:227–35. 10.1016/j.jval.2019.09.2747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Powers JH, Bacci ED, Leidy NK, et al. Performance of the inFLUenza patient-reported outcome (FLU-PRO) diary in patients with inFLUenza-like illness (ILI). PLoS One 2018;13:e0194180. 10.1371/journal.pone.0194180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seligman WH, Das-Gupta Z, Jobi-Odeneye AO, et al. Development of an international standard set of outcome measures for patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the International Consortium for health outcomes measurement (ICHOM) atrial fibrillation Working group. Eur Heart J 2020;41:1132–40. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-051065supp001.pdf (1MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-051065supp002.pdf (40.5KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Data are available upon reasonable request. These include complete survey results as well as results of the consensus-gathering processes described within the manuscript.