Abstract

3D bioprinting has emerged as an important tool to fabricate scaffolds with complex structures for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine applications. For extrusion-based 3D bioprinting, the success of printing complex structures relies largely on the properties of bioink. Methylcellulose (MC) has been exploited as a potential bioink for 3D bioprinting due to its temperature-dependent rheological properties. However, MC is highly soluble and has low structural stability at room temperature, making it suboptimal for 3D bioprinting applications. In this study, we report a one-step synthesis protocol for modifying MC with norbornene (MCNB), which serves as a new bioink for 3D bioprinting. MCNB preserves the temperature-dependent reversible sol-gel transition and readily reacts with thiol-bearing linkers through light-mediated step-growth thiol-norbornene photopolymerization. Furthermore, we rendered the otherwise inert MC network bioactive through facile conjugation of integrin-binding ligands (e.g., CRGDS) or via incorporating cell-adhesive and protease-sensitive gelatin-based macromer (e.g., GelNB). The adaptability of the new MCNB-based bioink offers an attractive option for diverse 3D bioprinting applications.

Keywords: methylcellulose, bioink, thiol-norbornene hydrogel, thermo-responsive, bioprinting

1. Introduction

Methylcellulose (MC) is a water soluble cellulose derivative synthesized by substitution of the hydrogen atom on hydroxyl group with a methyl group at the positions C-2, C-3, and/or C-6 [1]. MC is approved in Europe, USA, and many other countries for food additives and drug supplements. It has also been widely used as a building block for fabricating functional biomaterials such as tissue engineering scaffolds [2–4], drug delivery systems [5, 6], and smart culture surfaces [7, 8]. MC has excellent biocompatibility and exhibits a temperature-dependent reversible sol-gel transition, with a lower critical solution temperature (LCST) depending on its molecular weight. For instance, the LCSTs of high molecular weights MC (e.g., 400 cP, 2 wt% in H2O) are in the range of 50–60°C [9, 10], whereas that of low molecular weights MC (e.g., 15 cP, 8 wt% in H2O) are between 35–37°C [2, 3]. At a temperature above LCST, hydrophobic interactions among MC chains would increase, leading to rapid physical gelation. The degree of MC thermal gelation could also be controlled by the degree of methyl group substitution and polymer concentration, as well as additives (e.g., salts) in the solution [11]. As the MC concentration or molecular weight increases, hydrophobic interactions between MC chains are promoted even at a lower temperature [12]. For example, the gelation temperature of MC decreases from 38.5°C at 6wt% to 31.7°C at 12 wt% with increasing MC concentration. On the other hand, increasing ionic salts (e.g., NaCl, Na2HPO4, CaCl2) in the MC solution results in a lower LCST due to the salting-out effect [2, 3, 11]. In particular, with the same concentration (0.1 M) of salt, LCST of MC drops from 37°C to 32°C with calcium chloride (CaCl2) and to 29.1°C with sodium phosphate dibasic [11].

With its thermo-responsiveness, MC has been exploited as a bioink for 3D bioprinting [13–16], an emerging biofabrication tool to generate scaffolds with complex geometries and architectures needed for many regenerative medicine applications. In particular, extrusion-based 3D bioprinting is a simple and diverse printing process that accommodates a wide range of printable biomaterials. The success of extrusion-based bioprinting relies largely on the rheological properties of the bioink, which should possess high printability while preserving cell viability during the printing process [17, 18]. MC is a promising material for bioprinting both as a structural or sacrificial (i.e., removed after printing) material owing to its excellent biocompatibility and controllable thermo-sensitive properties [19, 20]. Compared with other bioinks (e.g., methacrylated-gelatin), MC-based bioinks showed high viscosity near the body temperature [21–26]. Bioinks with low viscosity cannot form uniform and continuous strand after passing through the nozzle. To mitigate this problem, bioink must be modified to rapidly solidify after extruding from the nozzle. Typically, the viscosity of polymer solution decreases with increasing temperature. As a result, the printability of polymer-based bioink decreases at higher temperature. However, MC has an unusual temperature-sensitive characteristic, with its viscosity increases as the temperature rises. Therefore, MC has been extensively studied as a viscosity-enhancing agent. It was commonly blended with other polymers to prepare bioinks for enhancing printability. Furthermore, due to its thermo-reversible property, MC can be easily removed from the printed constructs by lowering the temperature [20]. For example, Zineh et al. described the bioprinting of cartilage scaffolds using a combination of MC, alginate, halloysite, and polyvinylidine fluoride [27]. Alginate/hallosite did not show good printability because of their low viscosity. Hence, viscous MC was added to improve the mechanical properties and printability of alginate/hallosite. After printing, MC was removed by simply lowering the temperature to below its LCST. Non-modified MC is commonly used as a thermo-responsive sacrificial material or for short term cell culture matrix [1]. However, thermally crosslinked MC scaffolds exhibit relatively low structural stability, limiting its use in printing thick scaffolds. Furthermore, MC has low cell affinity since it contains no integrin binding ligands (e.g., arg-gly-asp or RGD), nor can it be degraded by cell-secreted proteases. To increase scaffold stability, Simone and colleagues designed methacrylated MC for photo-crosslinking into more stable MC hydrogels for long-term soft tissue reconstruction [28]. Li et al. presented alginate/MC blend hydrogel as thixotropic bioink [29]. In another example, Rastin et al. prepared 3D printed gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA)/MC interpenetrating network hydrogels [30]. While these approaches are effective in improving the structural stability of MC, the inherent temperature sensitive properties of MC are often lost in these macromers due to the changes in hydrophilic/hydrophobic segment balance of the modified MC.

More recently, Ji et al., designed photo-crosslinkable carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) bioink through norbornene (NB) functionalization [31]. While the NB functional group permit orthogonal photo-crosslinking, CMC itself does not exhibit thermo-reversible sol-gel transition since it lacks methoxy groups that give rise to thermosensitivity. Finally, Delplace et al. designed biorthogonal injectable low density MC hydrogel crosslinked by mutually reactive NB- and methylphenyltetrazine-functionalized MCs. The injectable and chemically crosslinked MC-based hydrogels showed excellent cytocompatibility and also has biodegradability owing to the di-sulfide bond present in the introduced 3,3’-dithiodipropionic acid dihydrazide group [32]. However, this work has not demonstrated the thermo-reversibility of MC, nor did it explore MCNB for bioprinting applications. In addition, the hydrogels reported exhibited relatively low mechanical stiffness (1–2 kPa, Young’s modulus) and slow gelation kinetics (~ 15 min).

Here, we report a one-step synthesis protocol for formulating norbornene-functionalized MC (MCNB) bioink for 3D bioprinting applications. MCNB exhibits good rheological properties and retains temperature sensitivity. Furthermore, the NB moiety readily reacts with a thiol group through light-mediated step-growth thiol-NB photopolymerization [33–36]. Due to its various merit for biological applications, thiol-NB photo click chemistry has been used extensively to form cell-laden hydrogels [33, 37–39], as well as for photo-patterning [40, 41] and 3D bioprinting [31, 42–44]. In this report, we demonstrate the thermo- and photo- dually responsive MCNB as a bioink for 3D bioprinting at 37°C to produce a network composed of both physical gelation and covalent thiol-norbornene crosslinks. The rheological properties, mechanical properties, and printability of the dually responsive MCNB were evaluated. Furthermore, we rendered the otherwise inert MC network bioactive through facile conjugation of integrin-binding and protease-labile motifs (i.e. CRGDS and GelNB). Finally, we demonstrated the usefulness of MCNB as a bioink to support the printing and culture of mouse mesenchymal stem cells (mMSCs).

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

The MC with a viscosity of 15 cP (Mw 110,000 g/mol, and DS 1.6–1.7) was obtained from LOTTE Fine Chemical Co., Ltd. Cold soluble gelatin was purchased from Instagel™. Carbic anhydride and triethyl amine (TEA) was purchased from Acros Organic. 4-arm-PEG-SH (PEG4SH) was purchased from Laysan Bio, Inc. Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. All other reagents were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific and used as received without further purification.

2.2. Synthesis of MCNB

MCNB was synthesized through the modification of hydroxyl group with carbic anhydride using TEA as a catalyst [45]. Briefly, 2.07 g of MC was dissolved in 100 ml distilled water for overnight. 5–10 mmol of carbic anhydride and 5–10 mmol of TEA were then added to the MC solution and the reaction was performed for 24 h. After this time, the products were purified by dialysis against water for 3 days (cellulose dialysis membrane, MWCO: 12,000–13,000). The final product was centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 5 min to remove insoluble aggregates during the process and lyophilized for 3 days. Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR, 500 MHz, ADVANCE III, Bruker, USA) was used to confirm the structural change, and the degree of NB substitution (DS, %) was defined as the number of substituents (δ 6.0–6.5 ppm, NB alkene proton) per total repeating unit in MC backbone (δ 2.5–3.2 ppm, H-2 proton). The DS was calculated using the following equation (1).

| (1) |

2.3. MCNB hydrogel fabrication and characterization

For experiments, MCNB hydrogels were fabricated by reacting PEG4SH via thiol-NB photoclick chemistry. Briefly, PEG4SH was mixed at a stoichiometric ratio of thiol to NB along with photoinitiator LAP (1 mM). The precursor solution with pre-defined compositions was injected between two glass slides separated by 1 mm Teflon spacers, followed exposure to 365 nm light (5 mW/cm2) for 2 min. In situ photo- and thermo- gelation studies were conducted using an oscillatory rheometer (Bohlin CVO 100). Briefly, MCNB solution containing thiol cross-linkers and photoinitiator LAP were mixed and vortexed for 5 s. Immediately after vortexing, 8 μl of the mixture was placed on the lower plate and the 8 mm plate geometry was lowered to 90 μm and in situ rheometry was performed in time sweep mode (0.5% strain at 1 Hz). To prevent gel from drying, the rim of the geometry was sealed with mineral oil. A temperature sweep from 25 to 45°C at a heating rate of 1°C/min was carried out to measure the gelation temperature. The gelation temperature of MC based bioink is defined as the cross-over point of storage modulus (G’) and loss modulus (G”). For light-mediated gelation, UV light was turned on 10 s after starting the measurement. Hydrogel shear moduli were measured using circular hydrogel discs fabricated between two glass slides. Gel discs were punched out with an 8 mm biopsy punch after 24 h incubation in PBS at 37°C. The hydrogels were carefully transferred to the rheometer prior to initiating the measurements and the frequency-sweep test was conducted at 1% strain. To determine the shear-thinning properties of MCNB bioink composition, steady rate sweeps were conducted by varying the shear rate from 0.1 s−1 to 100 s−1, and the stresses were measured at different shear rates. To evaluate recoverability of the material, oscillatory time sweeps were performed in 2 min intervals at alternating 100 and 1% strains performed at 1 Hz (n=4).

2.4. Printability test

To evaluate temperature-sensitivity of modified MC, we tested the printability of MCNB bioink at room temperature (25°C) and near LCST of MCNB (37°C). A Cellink BioX 3D printer (Cellink) was used for printing all constructs. Ink compositions were loaded into 3 ml cartridge at 25 and 37°C equipped with 22-gauge high-precision conical printing nozzle (15–30 kPa extrusion pressure, and 3–5 mm/s printing speed). STL files were generated from TinkerCad website and converted to G-code using Slicer (20×20×5 mm lattice structure-5 layers with 10–20% infill density, ear, nose, and liver structure). G-code files were then input into BioX printer which can controlled the printing parameter. Constructs were printing onto petri-dishes or in 3 wt% nanosilicate support bath [46]. A nanosilicate support bath was used to facilitate the printing of complex 3D structures. After printing, the constructs were crosslinked with built-in UV light (5 cm height for 2 min). Constructs were dyed with food coloring and imaged using digital camera and LionHeart (FX, Biotek). Images were processed and analyzed in ImageJ software to quantify the pore area (n=4).

2.5. Cell study and 3D bioprinting

Mouse mesenchymal stem cells (mMSCs) were cultured using DMEM high glucose supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% pentamycin/streptomycin. mMSCs cells were encapsulated in MCNB hydrogels at 2 M cells/ml. The cells were mixed with steriled-filtered (0.22 μm) pre-polymer solutions containing MCNB, PEG4SH, CRGDS, GelNB and LAP (1 mM). GelNB was synthesized according to previously reported method [30]. The solution was mixed and pipetted into a 1 ml syringe with cut-open tip. Cell-laden gels were formed upon exposure to 365 nm light (5 mW/cm2) for 2 min and were placed in a non-treated 24-well plate with fresh media. Media was refreshed every 2 days. At predetermined time periods (day 2, 4, 7 and 10), cell-laden hydrogels were stained with Live/Dead kit. To determine the spreading of the mMSCs, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) at 4°C for overnight. Samples were stained with F-actin using rhodamine phalloidin (1:200) at 4°C for overnight and washed. Finally, cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (1:1000) for 1 h, and washed. Samples were imaged by confocal microscopy (Olympus Fluoview FV100) at 10x and 20x objectives. All image processing and analysis was done using ImageJ. Thereafter morphology was quantified by calculating cell area and circularity, which corresponds to a value of 1 for a perfect circle using ImageJ software for each condition.

Inks for cell incorporation were fabricated by mix the bioink with mMSCs prior to the printing (2 M cells/ml). The cell-laden ink MCNB was loaded and printed as previously described onto petri-dishes. Constructs were then cross-linked with UV light for 2 min, rinsed with 1x PBS and incubated at 37°C until further analysis. In order to visualize cells encapsulated within bioinks, cells were stained with Live/Dead kit and imaged by confocal microscopy.

2.6. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8 software. Significance comparison between experimental groups was performed using two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post testing. All experiments were conducted a minimum of three times with data presentation as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). One, two, or three asterisks represent p < 0.05, 0.01, or 0.001, respectively.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Synthesis and gelation behavior of MCNB conjugates

NB moieties was conjugated to hydroxyl groups on MC using carbic anhydride in a single-step reaction (Figure 1A) and the resulting MCNB was characterized using 1H NMR (Figure S1A). Unmodified MC has strong signal at 3.6 ppm corresponding to the overlapping of methyl proton at C2 and C3, and at 3.4 ppm attributed to methyl protons at C6. Furthermore, H2, H4, H6 signals were represented at 3.0–3.2 ppm, 3.6 ppm (shoulder peak), and 3.7–4.0 ppm, respectively [4]. The signals at 6.2–6.4 ppm represent NB peaks that increased with increasing carbic anhydride/TEA concentration. NMR results show that MCNB was successfully synthesized, with the final DS ranged between 2.7% to 4.4% for 5 to 10 mmol of carbic anhydride, respectively. While norbornene-functionalized MC was recently reported by Delplace et al., the synthesis involves two sequential reactions [32]. First, MC was carboxylated via Williamson ether synthesis, followed by a secondary conjugation of NB functional group via amidation (DS approximately 1.6%). Methylphenyltetrazine was also reacted with disulfide-containing linker, namely, 3,3’-dithiopropionic acid dihydrizide functionalized MC (MC-DTP) via amidation to produce redoxcleavable MC-DTP-Tz (DS approximately 2.8%). The two functionalized MCs (i.e., NB and methyltetrazine-modified MCs) were mixed together for gelation through an inverse electron demand Diels-Alder reaction (iEDDA). In contrast, the MCNB reported in this study was synthesized by a simple one-step reaction, where NB was conjugated via esterification between hydroxylates of MC and carbic anhydride. Despite the simple process, we obtained higher functional group conversion (2.7% to 4.4%) as compared with the two-step synthesis protocol reported recently (~1.6%) [26].

Figure 1. Synthesis and gelation behavior of MCNB hydrogels.

(A) Schematic of MCNB synthesis. (B) Digital images of thermally gelled unmodified MC and MCNB hydrogels (at 37°C for 30 min). (C) Thermo-rheometry (8 wt% MCNB, 1°C/min), and (D) in situ photo-rheometry (8 wt% MCNB with PEG4SH, Rthiol/NB=0.8, 1mM LAP) of MCNB hydrogel crosslinking.

We reasoned that the thermo-responsivity of MC could improve the printability, while thiol-norbornene crosslinking would enhance the structural stability of the 3D printed structure. To assess the thermo-responsiveness of MCNB, rheological characteristics were characterized as a function of temperature. 8 wt% MCNB solutions stored at 37°C for 30 min formed a hydrogel through hydrophobic interaction (Figure 1B). Temperature-sweep rheological testing revealed typical LCST behavior of both MC and MCNB (Figure 1C). Specifically, unmodified MC and MCNB exhibited an LCST of 33°C and 38°C, respectively. Although the introduction of NB groups raised the LCST, the temperature required for thermal-induced gelation remained close to the body temperature [47]. However, as the DS increased from 2.7% to 4.4%, the temperature required for thermo-gelation increased to above 40°C (data not shown). Therefore, further experiment was carried out with 2.7% substitution of MCNB. Using in situ photo-rheometry, we demonstrated rapid thiol-NB gelation kinetics of MCNB and PEG4SH (Figure 1D, Figure S1B). Specifically, light-mediated sol-gel transition occurred rapidly (crossover of G’ and G” or gel point ~ 10 s) and reached completion within 30 s, which was on par with other UV light initiated thiol-NB gelation systems [48–51]. In comparison, the CMC-NB bioink previously designed by Ji et al. showed a gelation time of 29 to 90 min depending on the thiol/NB ratio, and the mechanism by which gelation occurred in the absence of UV light of CMC-NB was not described in detail [31]. In addition, despite the high degree of NB substitution on CMC (20–30% per repeating unit), there was no significant improvement in the gelation time using photopolymerization.

3.2. Shear thinning properties and 3D printability of MCNB bioinks

Unmodified MC, MCNB, and MCNB with PEG4SH were subjected to viscometry test. As shown in Figure 2A, viscosity of all three MC-based bioinks decreased with shear rate, suggesting that all of them are shear-thinning materials. However, NB modification lower the viscosity considerably, suggesting that NB modification reduced chain entanglement of MC, which is consistent with the temperature-sensitive gelation results (Figure 1C). However, as a result of introducing PEG4SH, the viscosity increases due to the salting-out effect. Specifically, PEG4SH is a highly hydrophilic macromer that may destabilize MC─H2O interactions and enhance the hydrophobic interactions between MC macromolecules. Therefore, the viscosity of the MCNB/PEG4SH mixture increased. In the optimization of printing parameters, viscosity of bioink is one of the crucial factors affecting printability and cell viability [52]. Modification of MC with NB groups decreased viscosity of the macromer. This negative effect was mitigated by the addition of PEG4SH, resulting in a bioink system with a good printability. After extruding from the nozzle, the high shear stress is relieved and should have the ability to recover the storage modulus and loss modulus of MCNB hydrogel quickly to its initial state [18, 23, 30, 53]. The shear thinning properties of MCNB bioink was also investigated by subjecting the bioink precursor solution to repeated low (1%) and high (100%) strains (Figure 2B) [54]. It was observed that storage modulus of MCNB bioink significantly decreased, from ~18 kPa to 0.25 kPa, when subjected to high strains, presenting a recovery of its G’ as the strain decreases to 1%. Next, extrusion study at different temperature was conducted to confirm the printability of MCNB bioink at different temperature (Figure 2C). MCNB bioink at 37°C formed a continuous line and extrude consistently from the nozzle. In contrast, at 25°C, the extruded MCNB bioink did not form a uniform strand and fell into droplets. Since MCNB exhibit an LCST at around 33°C, bioink extruded above LCST exhibited better resolution due to the increase in physical crosslinking through hydrophobic interaction. When printing at 37°C, both unmodified MC and MCNB showed good printability even in the absence of any rheological modifier (i.e. glycerol, cellulose nanofiber, silicate nanoparticles) or supporting bath (i.e. FRESH or Carbopol) (Figure 2D) [55]. However, when the temperature was dropped to ambient level, the printed 3-layer MC structure collapsed due to gel-sol transition. On the other hand, hydrogel structures printed with MCNB could be reinforced via thiol-NB photocrosslinking, resulting in a stable structure regardless of temperature. Due to the collapse of 3D printed lattice structure of unmodified MC, the lattice pore size decreased from 0.032 ± 0.003 mm2 to 0.014 ± 0.002 mm2, and the strand diameter increased form 202.4 ± 24.9 μm to 375.0 ± 26.5 μm respectively.

Figure 2. Shear-thinning and printability tests.

(A) Shear rate sweep revealing the shear-thinning property of MC and MCNB bioinks. (B) Shear-thinning (i.e., G’<<G”) of MCNB at high strain (100%). G’ of MCNB recovered rapidly when strain was dropped to 1%. (C) MCNB was extruded as droplets at 25°C, but formed a continuous string at 37°C. (D) Effect of thiol-norbornene photo-crosslinking on improving structural stability of three-layered lattice MCNB constructs.

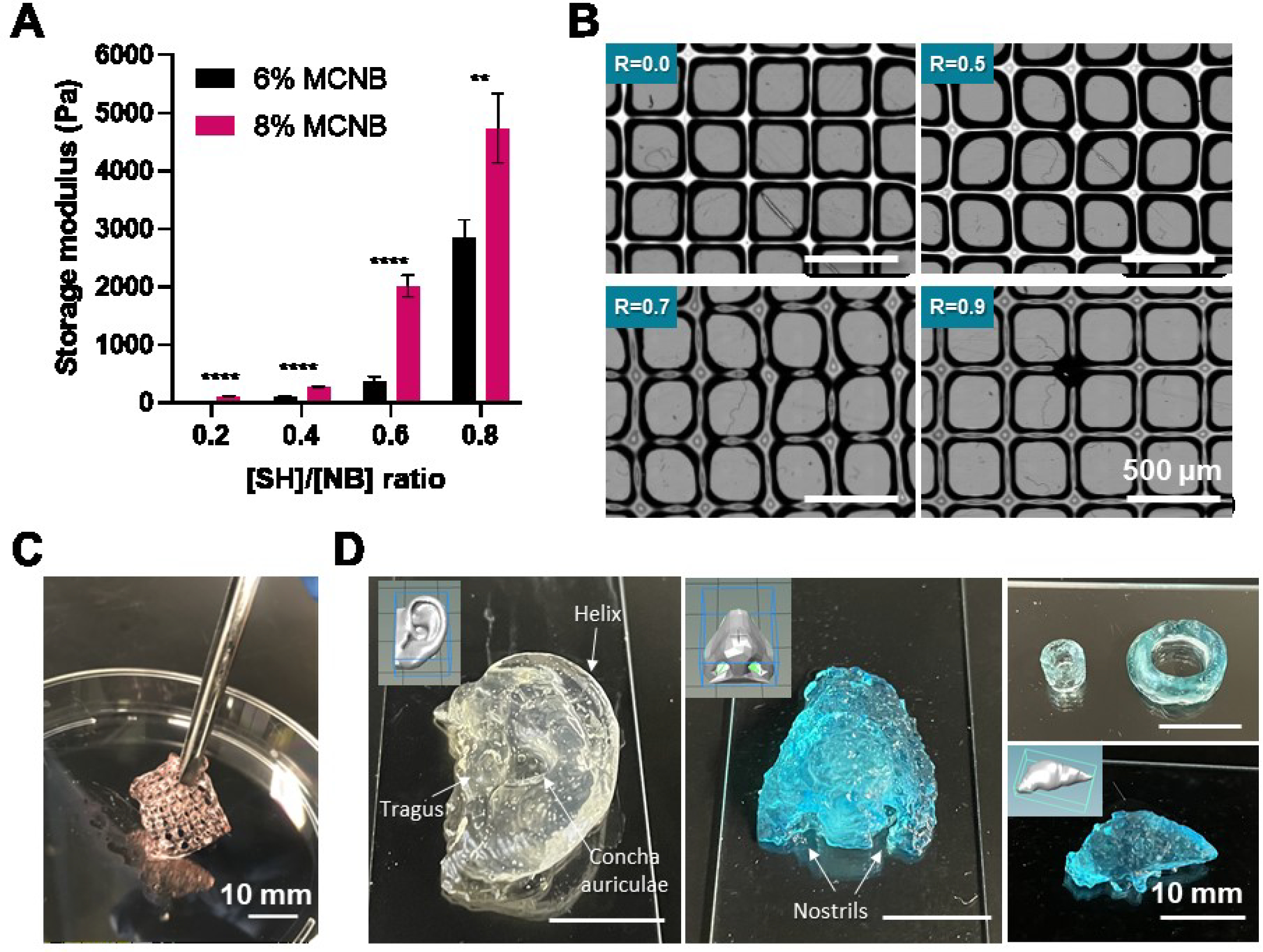

3.3. Bioprinting of MCNB

Prior to testing MCNB in bioprinting, mechanical properties of photo-crosslinked MCNB hydrogels were evaluated at 6% and 8% of MCNB, as well as macromers at different Rthiol/NB (Figure 3A). As expected, the shear moduli of MCNB-based thiol-norbornene hydrogels increased as the macromer concentration. Furthermore, adjusting Rthiol/NB ratio from 0.2 to 0.8 led to increased gel crosslinking density and shear moduli, from 105 ± 8 Pa to 4,738 ± 600 Pa. Interestingly, increasing Rthiol/NB did not affect printability (Figure 3B) because printing was carried out at a temperature above LCST of the bioinks [56]. In addition, additional thiol-NB photo-crosslinking improved the mechanical strength and structural stability of the printed scaffolds (Figure 3C). In previous bioprinting studies, MC only played a supporting role (i.e., as a thickener) through blending with other biomaterials. Beside increasing viscosity of the blended bioink, MC was used as a sacrificial material and was washed away post-printing [1]. On the other hand, the MCNB synthesized in this study served as a structural component. Bioinks composed of MCNB maintained proper viscosity for bioprinting. The printed structure can then be reinforced through an additional thiol-NB photocrosslinking.

Figure 3. 3D printing of MCNB.

(A) Effect of macromer concentration and [SH]:[NB] ratio on MCNB hydrogel stiffness. (B) Effect of [SH]:[NB] ratio on printability of MCNB bioinks. (C) Digital image of dually crosslinked MCNB 3D printing construct. (D) Digital images of 3D printed complex structure using MCNB bioinks in support bath (nanosilicate solution).

Generally, the complexity of 3D printed microstructures is limited when using soft hydrogel bioinks (<100 kPa) [57]. Direct printing of bioink in various support bath (i.e. gelatin particle, alginate microparticles, carbopol, nanosilicate suspension) have been used to improve the printing complexity of soft biological hydrogel bioinks [58, 59]. In order to demonstrate the ability to print complex shapes of MCNB bioinks, we printed a variety of constructs in 3 wt% nanosilicate support bath (Figure 3D). The MCNB bioinks can be used to print anatomical-size structures such as ear, nose, vessel and liver structure. The 3D printed complex structure was stabilized through photocrosslinking, and the nanosilicate support bath can be easily removed by immersing in distilled water.

3.3. Cytocompatibility and 3D bioprinting using MCNB bioinks

Ensuring cell viability during bioprinting is critical to bioink development [60]. To this end, Live/Dead staining was performed to assess viability of bioprinted mMSCs. Figure 4A showed that the almost all of the mMSCs remained alive after the extrusion-based bioprinting. Furthermore, encapsulated mMSCs in MCNB hydrogel showed excellent viability after 10 days of culture and few dead cells were observed (Figure S2). Biochemical properties of the thiol-norbornene hydrogels can be readily controlled by incorporating bioactive ligands (e.g., RGDS, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) sensitive peptides) [37]. Here, CRGDS was co-polymerized to improve the bioactive properties of MCNB hydrogels (Figure 4B). Upon detailed examination of cell morphology using confocal microscopy, we found that mMSCs encapsulated in MCNB hydrogels without CRGDS did not spread and the cells remained in a round morphology over 10 days of culture. However, mMSCs spreading was observed as early as day 4 post encapsulation in MCNB hydrogel immobilized with CRGDS. Circularity of mMSCs was characterized to confirm the effect of CRGDS on enhancing cell spreading (Figure 4C). Interestingly, spreading of mMSCs were observed in the absence of MMP degradable sequence. This is assumed to be due to the hydrolytic degradation of MCNB hydrogel (Figure S3). The degradation of MCNB hydrogel was expected as NB was conjugated to MC via an ester linkage between the hydroxyl group in MC and carboxyl group in carbic anhydride [50]. If undesirable, however, hydrolytic degradation can be prevented by synthesizing MCNB of amide-linkage using aminated MC which can be obtained through reaction with epichlorohydrin under basic condition [61].

Figure 4. Cytocompatibility of MCNB in 3D bioprinting.

(A) Live/Dead staining and confocal images of 3D bioprinted MCNB bioinks with mMSCs. (B) Representative immunostaining of encapsulated mMSCs in MCNB hydrogels with/without CRGDS. (C) Effect of CRGDS on cell circularity of the encapsulated mMSCs in MCNB hydrogels at D7.

3.4. Rheological properties and printability of MCNB/GelNB composite bioinks

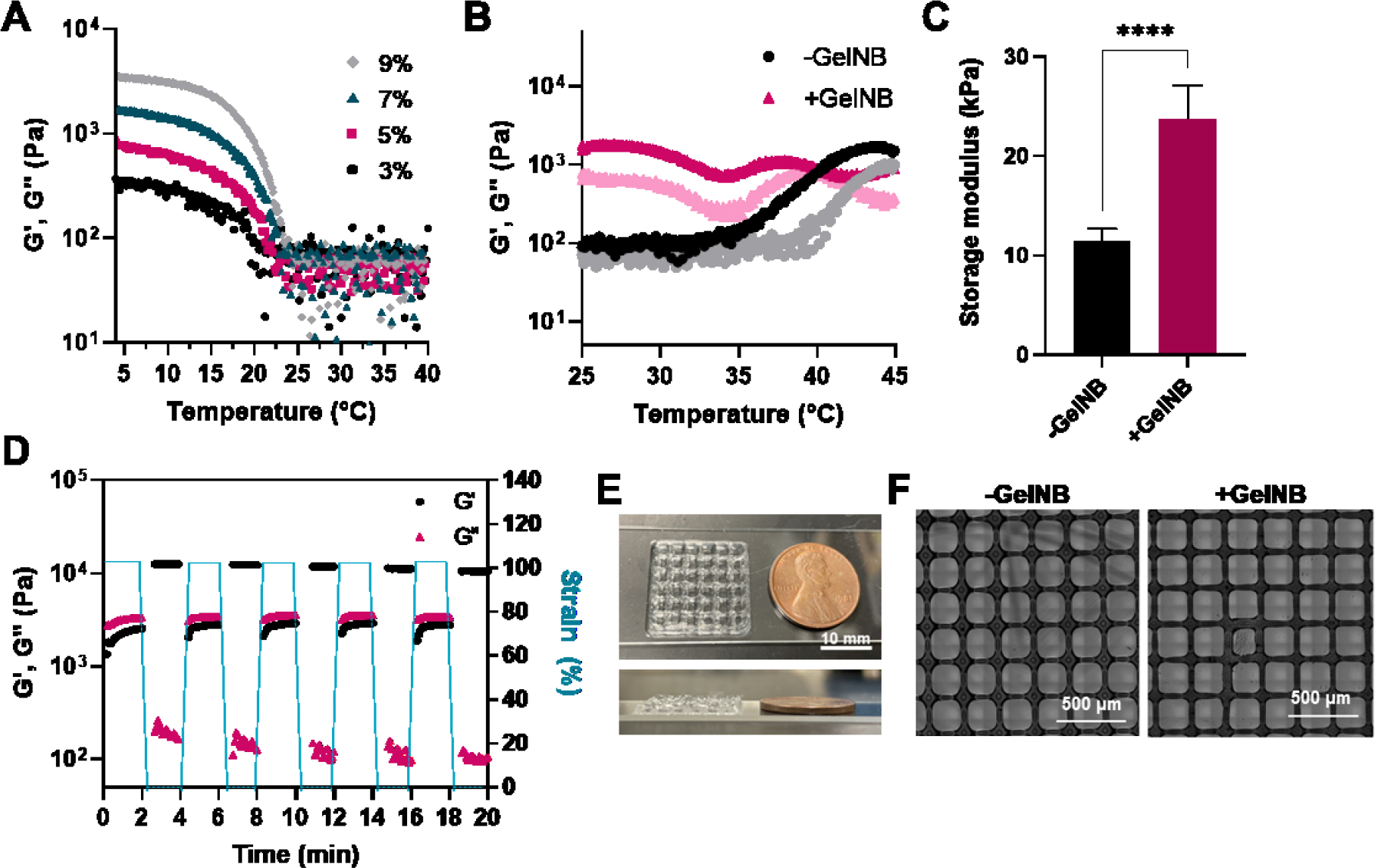

Another option to improve bioactivity of the otherwise inert MC/MCNB bioink is to blend with thiolated gelatin or norbornene-functionalized gelatin (i.e., GelNB) [36, 62, 63]. The use of thiolated gelatin can minimize the use of macromers used in bioink components [64–66]. However, the stability of thiolated gelatin made for bioink was low and easily oxidized to form disulfide crosslinking before the mixing. In addition, the synthesis of thiolated gelatin is carried out under acidic region which can minimized the oxidation of thiol, and it is troublesome to adjust the pH to the physiological range for bioprinting. Of note, gelatin has an opposite temperature-responsive characteristic to that of MC, and sol-gel transition occur due to the increase of hydrogen bonds at temperature below upper critical solution temperature (UCST). We hypothesized that the rheological properties of MCNB bioink at below the LCST can be reinforced by blend with gelatin macromer. GelNB was synthesized following a previous reported method using cold soluble gelatin [67]. The temperature-sensitivity of GelNB was characterized via temperature sweep rheometry. As the temperature increased, GelNB exhibited a gel-sol transition at around 21°C regardless of weight content (3–9 wt%), which affected the shear moduli of the physically crosslinked GelNB hydrogels at temperature below the UCST (Figure 5A).

Figure 5. Rheological properties and 3D printing of MCNB /GelNB composite bioinks.

(A) Thermo-responsive properties of GelNB conjugates according to concentration. (B) Effect of introduction of 3 wt% GelNB on thermo-responsive property of MCNB bioink. (C) Storage modulus of MCNB/GelNB composite hydrogel. (D) Shear-thinning (i.e., G’<<G”) of MCNB/GelNB composite bioink at high strain (100%). G’ of MCNB/GelNB composite bioink recovered rapidly when strain was dropped to 1%. (E) Digital images of 3D printed MCNB/GelNB composite bioink. (F) Effect of introduction of GelNB on printability of bioink at 37°C.

Given that GelNB and MCNB have the opposite direction in the thermo-responsiveness, we tested the temperature-responsiveness of blending GelNB with MCNB bioink (Figure 5B). In the absence of GelNB, sol-gel transition occurred at 37°C. However, in case of MCNB/GelNB composite bioink, gel-like behavior (G’>G”) was observed even at room temperature, and G’ value was maintained higher level than that of MCNB in the temperature range of 25°C to 37°C. This results showed that MCNB and GelNB, which have opposite temperature-sensitive properties, were mixed and complementarily affect gelation, resulting in gel-like behavior even at temperature above UCST of GelNB and below LCST of MCNB. At a temperature below LCST of MC, hydrogen bonding of gelatin is promoted by MC and gel-like behavior appears. Conversely, gel-sol transition of gelatin occurs above LCST and salting-out effect is promoted, resulting in gel-like behavior. Likewise, the mechanical properties of the composite hydrogel increased (11.4 kPa to 23.7 kPa) with introduction of GelNB (Figure 5C). The excellent recovery properties of MCNB/GelNB bioink was also observed that storage modulus of composite bioink decreased when subjected to alternating high and low strains, presenting a recovery of its G’ although enhanced the rheological property by GelNB (Figure 5D). One of our goal through composite with GelNB is to improve the printability of MCNB bioink. Therefore, the printability of MCNB/GelNB composite bioink was evaluated at 37°C (Figure 5E, 5F). MCNB/GelNB composite bioink showed excellent printability, and printing layer stacking property was improved with the introduction of GelNB (3 layer to 7 layer). In case of the pore structure of printed lattice constructs, more square-shaped pores were formed as GelNB was introduced, and the pore size was closer to the ideal pore size (Figure S4).

3.5. Printability and bioactivity of MCNB/GelNB composite bioinks

Given that MCNB/GelNB composite bioink exhibited desired rheological and shear-thinning property, we tested the printability of MCNB/GelNB composite bioink at room temperature (Figure 6A). As expected, the introduction of hydrophilic GelNB yielded a composite non-crosslinked bioink with gel-like property at room temperature (Figure 5B) and produced a clear lattice print even at temperature below LCST. In contrast, MCNB bioink (i.e., without GelNB) failed to form a stable lattice print since pure MCNB was in a solution state at temperature below its LCST. Furthermore, GelNB bioinks printed a clear lattice print at below UCST (10°C), but failed to form a stable lattice when printed at room temperature. This is because GelNB was not viscous enough at temperature above its UCST (Figure S5). Figure 6B showed that the majority of the encapsulated mMSCs were alive and showed excellent cell survival after 10 days of culture. To confirm the enhanced bioactive properties of MCNB/GelNB composite hydrogels, morphologies of encapsulated mMSCs following the introduction of GelNB were observed (Figure 6C). Spreading of mMSCs were observed in MCNB/GelNB composite hydrogels after 4 days, which was similar to the effect of CRGDS (Figure 6D). Cell circularity of mMSCs was also significantly reduced due to the introduction of GelNB in the MCNB hydrogel. The main drawback of MC-based hydrogels in 3D cell encapsulation is low cell adhesiveness and cell proliferation, since it contains no moieties linked to cellular adhesion. Gelatin is a denatured collagen derivative containing RGD sequence essential for cell adhesion to the matrix. It is possible to enhance the interaction between encapsulated mMSCs and bioinks through incorporating gelatin derivatives into MC as a composite hydrogel. In addition, spreading of mMSCs occurred without introducing MMP degradable sequence due to the hydrolytic degradable properties of MCNB/GelNB composite bioinks (Figure S3). Collectively, the introduction of GelNB into the MCNB bioink enhanced both printability and bioactivity of the printed constructs.

Figure 6. Bioprinting with GelNB/MCNB hybrid bioink.

(A) Effect of GelNB introduction on printability of bioinks at 25°C (8 wt% MCNB with 3 wt% GelNB crosslinked with PEG4SH Rthiol/NB=0.8, 1 mM LAP, 2 min light after printing). (B) Representative confocal live/dead images of mMSCs encapsulated in MCNB/GelNB composite hydrogel. (C) F-actin staining images of mMSCs encapsulated in MCNB and MCNB/GelNB composite hydrogel. (D) Effect of GelNB on cell circularity of the encapsulated mMSCs in MCNB hydrogels at D7.

4. Conclusion

In summary, we have prepared MCNB, a new bioink that can be crosslinked by temperature-induced gelation or orthogonal thiol-norbornene chemistry. The new MCNB retained temperature responsiveness of MC while permitting covalent crossliking post-printing to enhance the stability of the 3D structure. The new bioink was cytocompatible and protected cell ability during printing owing to its shear-thinning property. The MCNB bioinks can be used to print anatomical-size structures with a support bath. By incorporating bioactive GelNB with MCNB, the composite bioink formulations improved the bioactivity of the printed matrix and enhanced the printability over a wide range of temperature. This study demonstrates the potential of novel thermo- and photo-responsive MC as a versatile bioink for bioprinting applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This project was supported by the National Cancer Institute (R01CA227737) and Indiana University Comprehensive Cancer Center via a Walther Cancer Foundation Oncology Physical Sciences & Engineering Research Embedding Program grant. The authors thank Dr. Hiroki Yokota for providing mouse mesenchymal stem cells.

Footnotes

Ethical Statement

No human subject was involved in this project. Mouse mesenchymal stem cells (mMSCs) were kindly provided by Dr. Hiroki Yokota (IUPUI). mMSCs were harvested from bone marrow-derived adherent cells that were collected from a pair femora of C57BL/6 female mouse. The experimental procedures using mice were approved by the Indiana University Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol number: SC292R) and were complied with the Guiding Principles in the Care and Use of Animals endorsed by the American Physiological Society.

5. Reference

- [1].Ahlfeld T, Guduric V, Duin S, Akkineni AR, Schütz K, Kilian D, Emmermacher J, Cubo-Mateo N, Dani SWitzleben MV, Spangenberg J, Abdelgaber R, Richter RF, Lode A and Gelinsky M 2020. Methylcellulose–a versatile printing material that enables biofabrication of tissue equivalents with high shape fidelity Biomater. Sci 8 2102–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kim MH, Kim BS, Park H, Lee J and Park WH 2018. Injectable methylcellulose hydrogel containing calcium phosphate nanoparticles for bone regeneration Int. J. Biol. Macromol 109 57–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kim MH, Park H, Nam HC, Park SR, Jung J-Y and Park WH 2018. Injectable methylcellulose hydrogel containing silver oxide nanoparticles for burn wound healing Carbohydr. Polym 181 579–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Nasatto PL, Pignon F, Silveira JL, Duarte MER, Noseda MD and Rinaudo M 2015. Methylcellulose, a cellulose derivative with original physical properties and extended applications Polymers 7 777–803 [Google Scholar]

- [5].Liu Z and Yao P 2015. Injectable thermo-responsive hydrogel composed of xanthan gum and methylcellulose double networks with shear-thinning property e132 490–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Pakulska MM, Vulic K, Tam RY and Shoichet MS 2015. Hybrid crosslinked methylcellulose hydrogel: a predictable and tunable platform for local drug delivery Adv. Mater 27 5002–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chen C-H, Tsai C-C, Chen W, Mi F-L, Liang H-F, Chen S-C and Sung H-W 2006. Novel living cell sheet harvest system composed of thermoreversible methylcellulose hydrogels Biomacromolecules 7 736–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lee W-Y, Chang Y-H, Yeh Y-C, Chen C-H, Lin KM, Huang C-C, Chang Y and Sung H-W 2009. The use of injectable spherically symmetric cell aggregates self-assembled in a thermo-responsive hydrogel for enhanced cell transplantation Biomaterials 30 5505–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Itoh K, Hatakeyama T, Kimura T, Shimoyama T, Miyazaki S, D’Emanuele A and Attwood D 2010. Effect of D-sorbitol on the thermal gelation of methylcellulose formulations for drug delivery Chem Pharm Bull 58 247–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Tang Y, Wang X, Li Y, Lei M, Du Y, Kennedy JF and Knill CJ 2010. Production and characterisation of novel injectable chitosan/methylcellulose/salt blend hydrogels with potential application as tissue engineering scaffolds Carbohydr. Polym 82 833–41 [Google Scholar]

- [11].Park H, Kim MH, Yoon YI and Park WH 2017. One-pot synthesis of injectable methylcellulose hydrogel containing calcium phosphate nanoparticles Carbohydr. Polym 157 775–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Morozova S 2020. Methylcellulose fibrils: a mini review Polym. Int 69 125–30 [Google Scholar]

- [13].Valarmathi N and Sumathi S 2020. Biomimetic hydroxyapatite/silkfibre/methylcellulose composites for bone tissue engineering applications New J. Chem 44 4647–63 [Google Scholar]

- [14].Taghipour YD, Hokmabad VR, Bakhshayesh D, Rahmani A, Asadi N, Salehi R and Nasrabadi HT 2020. The application of hydrogels based on natural polymers for tissue engineering Curr. Med. Chem e 2658–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Yang Y, Lu YT, Zeng K, Heinze T, Groth T and Zhang K 2020. Recent Progress on Cellulose-Based Ionic Compounds for Biomaterials Adv. Mater e e2000717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Negrini NC, Bonetti L, Contili L and Farè S 2018. 3D printing of methylcellulose-based hydrogels e10 e00024 [Google Scholar]

- [17].Berg J, Hiller T, Kissner MS, Qazi TH, Duda GN, Hocke AC, Hippenstiel S, Elomaa L, Weinhart M, Fahrenson C and Kurreck J 2018. Optimization of cell-laden bioinks for 3D bioprinting and efficient infection with influenza A virus Sci. Rep 8 1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Daly AC, Prendergast ME, Hughes AJ and Burdick JA 2021. Bioprinting for the Biologist Cell 184 18–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gungor-Ozkerim PS, Inci I, Zhang YS, Khademhosseini A and Dokmeci MR 2018. Bioinks for 3D bioprinting: an overview Biomater. Sci 6 915–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Bonetti L, De Nardo L and Farè S 2020. Thermo-responsive methylcellulose hydrogels: from design to applications as smart biomaterials Tissue Eng. Part B Rev [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Jia J, Richards DJ, Pollard S, Tan Y, Rodriguez J, Visconti RP, Trusk TC, Yost MJ, Yao H and Markwald RR and Mei Y 2014. Engineering alginate as bioink for bioprinting Acta Biomater. 10 4323–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Axpe E and Oyen ML 2016. Applications of alginate-based bioinks in 3D bioprinting Int. J. Mol. Sci 17 1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Liu W, Heinrich MA, Zhou Y, Akpek A, Hu N, Liu X, Guan X, Zhong Z, Jin X, Khademhosseini A Zhang YS 2017. Extrusion bioprinting of shear-thinning gelatin methacryloyl bioinks Adv. Healthc. Mater 6 1601451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Billiet T, Gevaert E, De Schryver T, Cornelissen M and Dubruel P 2014. The 3D printing of gelatin methacrylamide cell-laden tissue-engineered constructs with high cell viability Biomaterials 35 49–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Müller M, Becher J, Schnabelrauch M and Zenobi-Wong M 2015. Nanostructured Pluronic hydrogels as bioinks for 3D bioprinting Biofabrication 7 035006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Chimene D, Lennox KK, Kaunas RR and Gaharwar AK 2016. Advanced bioinks for 3D printing: a materials science perspective Ann. Biomed. Eng 44 2090–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Zineh BR, Shabgard MR and Roshangar L 2018. Mechanical and biological performance of printed alginate/methylcellulose/halloysite nanotube/polyvinylidene fluoride bio-scaffolds Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl 92 779–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Stalling SS, Akintoye SO and Nicoll SB 2009. Development of photocrosslinked methylcellulose hydrogels for soft tissue reconstruction Acta Biomater. 5 1911–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Li H, Tan YJ, Leong KF and Li L 2017. 3D bioprinting of highly thixotropic alginate/methylcellulose hydrogel with strong interface bonding ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9 20086–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Rastin H, Ormsby R, Atkins G and Losic D 2020. 3D Bioprinting of Methylcellulose/Gelatin-Methacryloyl (MC/GelMA) Bioink with High Shape Integrity ACS Appl. Bio Mater e 1815–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Ji S, Abaci A, Morrison T, Gramlich WM and Guvendiren M 2020. Novel bioinks from UV-responsive norbornene-functionalized carboxymethyl cellulose macromers Bioprinting 18 e00083 [Google Scholar]

- [32].Delplace V, Pickering AJ, Hettiaratchi M, Zhao S, Kivijärvi T and Shoichet MS 2020. Inverse Electron-Demand Diels-Alder Methylcellulose Hydrogels Enable the Co-Delivery of Chondroitinase ABC and Neural Progenitor Cells Biomacromolecules 21 2421–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Nguyen HD, Liu H-Y, Hudson BN and Lin C-C 2019. Enzymatic Cross-Linking of Dynamic Thiol-Norbornene Click Hydrogels ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng 5 1247–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Shih H, Liu H-Y and Lin C-C 2017. Improving gelation efficiency and cytocompatibility of visible light polymerized thiol-norbornene hydrogels via addition of soluble tyrosine Biomater. Sci 5 589–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Shih H, Greene T, Korc M and Lin C-C 2016. Modular and adaptable tumor niche prepared from visible light initiated thiol-norbornene photopolymerization Biomacromolecules 17 3872–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Mũnoz Z, Shih H and Lin C-C 2014. Gelatin hydrogels formed by orthogonal thiol–norbornene photochemistry for cell encapsulation Biomater. Sci 2 1063–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Lin CC, Ki CS and Shih H 2015. Thiol–norbornene photoclick hydrogels for tissue engineering applications J. Appl. Polym. Sci 132 41563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Fairbanks BD, Schwartz MP, Halevi AE, Nuttelman CR, Bowman CN and Anseth KS 2009. A versatile synthetic extracellular matrix mimic via thiol-norbornene photopolymerization Adv. Mater 21 5005–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kim MH and Lin C-C 2021. Assessing monocyte phenotype in poly (γ-glutamic acid) hydrogels formed by orthogonal thiol-norbornene chemistry Biomed. Mater 16 045027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Gramlich WM, Kim IL and Burdick JA 2013. Synthesis and orthogonal photopatterning of hyaluronic acid hydrogels with thiol-norbornene chemistry Biomaterials 34 9803–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Lyon GB, Cox LM, Goodrich JT, Baranek AD, Ding Y and Bowman CN 2016. Remoldable thiol–ene vitrimers for photopatterning and nanoimprint lithography Macromolecules 49 8905–13 [Google Scholar]

- [42].Van Belleghem S, Torres L Jr, Santoro M, Mahadik B, Wolfand A, Kofinas P and Fisher JP 2020. Hybrid 3D Printing of Synthetic and Cell-Laden Bioinks for Shape Retaining Soft Tissue Grafts Adv. Funct. Mater 30 1907145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Dobos A, Van Hoorick J, Steiger W, Gruber P, Markovic M, Andriotis OG, Rohatschek A, Dubruel P, Thurner PJ and Van Vlierberghe S 2019. Thiol–Gelatin–Norbornene Bioink for Laser-Based High-Definition Bioprinting Adv. Healthc. Mater e1900752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Highley CB, Song KH, Daly AC and Burdick JA 2019. Jammed microgel inks for 3D printing applications Adv. Sci 6 1801076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Xin P-P, Huang Y-B, Hse C-Y, Cheng HN, Huang C and Pan H 2017. Modification of cellulose with succinic anhydride in TBAA/DMSO mixed solvent under catalyst-free conditions Materials 10 526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Jin Y, Compaan A, Chai W, Huang Y 2017. Functional nanoclay suspension for printing-then-solidification of liquid materials e9 20057–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Shin JY, Yeo YH, Jeong JE, Park SA and Park WH 2020. Dual-crosslinked methylcellulose hydrogels for 3D bioprinting applications Carbohydr. Polym 238 116192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Shih H and Lin C-C 2012. Cross-linking and degradation of step-growth hydrogels formed by thiol–ene photoclick chemistry e13 2003–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Nguyen HD, Liu H-Y, Hudson BN, Lin C-C 2019. Enzymatic cross-linking of dynamic thiol-norbornene click hydrogels ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng 5 1247–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Lin F-Y and Lin C-C 2021. Facile Synthesis of Rapidly Degrading PEG-Based Thiol–Norbornene Hydrogels e10 341–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Mũnoz Z, Shih H and Lin C-C 2014. Gelatin hydrogels formed by orthogonal thiol– norbornene photochemistry for cell encapsulation Biomater. Sci 2 1063–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Chopin-Doroteo M, Mandujano-Tinoco EA and Krötzsch E 2020. Tailoring of the rheological properties of bioinks to improve bioprinting and bioassembly for tissue replacement Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj 1865 129782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Chen Y, Xiong X, Liu X, Cui R, Wang C, Zhao G, Zhi W, Lu M, Duan K, Weng J, Qu S and Ge J 2020. 3D Bioprinting of shear-thinning hybrid bioinks with excellent bioactivity derived from gellan/alginate and thixotropic magnesium phosphate-based gels e8 5500–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Wilson SA, Cross LM, Peak CW and Gaharwar AK 2017. Shear-thinning and thermos-reversible nanoengineered inks for 3D bioprinting ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9 43449–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Chen S, Tan WS, Juhari MAB, Shi Q, Cheng XS, Chan WL and Song J 2020. Freeform 3D printing of soft matters: recent advances in technology for biomedical engineering e 1–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Kim MH, Lee JN, Lee J, Lee H, Park WH 2020. Enzymatically cross-linked poly (γ-glutamic acid) hydrogel with enhanced tissue adhesive property ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng 6 3103–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Hinton TJ, Jallerat Q, Palchesko RN, Park JH, Grodzicki MS, Shue H-J, Ramadan MH, Hudson AR and Feinberg AW 2015. Three-dimensional printing of complex biological structures by freeform reversible embedding of suspended hydrogels Sci. Adv 1 e1500758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Noor N, Shapira A, Edri R, Gal I, Wertheim L and Dvir T 2019. 3D printing of personalized thick and perfusable cardiac patches and hearts Adv. Sci 6 1900344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].McCormack A, Highley CB, Leslie NR and Melchels FPW 2020. 3D printing in suspension baths: keeping the promises of bioprinting afloat Trends Biotechnol. 38 584–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Ozbolat IT and Hospodiuk M 2016. Current advances and future perspectives in extrusion-based bioprinting Biomaterials 76 321–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Cook J. Amine Functionalization of Bacterial Cellulose for Targeted Delivery Applications. 2013.

- [62].Rajabi N, Kharaziha M, Emadi R, Zarrabi A, Mokhtari H, Salehi S 2020. An adhesive and injectable nanocomposite hydrogel of thiolated gelatin/gelatin methacrylate/Laponite® as a potential surgical sealant e564 155–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Kim MH, Nguyen H, Chang C-Y, Lin C-C 2021. Dual Functionalization of Gelatin for Orthogonal and Dynamic Hydrogel Cross-Linking ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Fu Y, Xu K, Zheng X, Giacomin AJ, Mix AW and Kao WJ 2012. 3D cell entrapment in crosslinked thiolated gelatin-poly (ethylene glycol) diacrylate hydrogels e33 48–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Russo L, Sgambato A, Visone R, Occhetta P, Moretti M, Rasponi M, Nicotra F and Cipolla L 2016. Gelatin hydrogels via thiol-ene chemistry e147 587–92 [Google Scholar]

- [66].Xu K, Cantu DA, Fu Y, Kim J, Zheng X, Hematti P and Kao WJ 2013. Thiol-ene Michael-type formation of gelatin/poly (ethylene glycol) biomatrices for three-dimensional mesenchymal stromal/stem cell administration to cutaneous wounds Acta Biomater. 9 8802–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Wang Z, Tian Z, Menard F and Kim K 2017. Comparative study of gelatin methacrylate hydrogels from different sources for biofabrication applications Biofabrication 9 044101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.