Abstract

Disruption of redox homeostasis in mycobacteria causes irreversible stress induction and cell death. Here, we report the dioxonaphthoimidazolium scaffold as a novel redox cycling antituberculosis chemotype with potent bactericidal activity against growing and nutrient-starved phenotypically drug-resistant nongrowing bacteria. Maximal potency was dependent on the activation of the redox cycling quinone by the positively charged scaffold and accessibility to the mycobacterial cell membrane as directed by the lipophilicity and conformational characteristics of the N-substituted side chains. Evidence from microbiological, biochemical, and genetic investigations implicates a redox-driven mode of action that is reliant on the reduction of the quinone by type II NADH dehydrogenase (NDH2) for the generation of bactericidal levels of the reactive oxygen species (ROS). The bactericidal profile of a potent water-soluble analogue 32 revealed good activity against nutrient-starved organisms in the Loebel model of dormancy, low spontaneous resistance mutation frequency, and synergy with isoniazid in the checkerboard assay.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

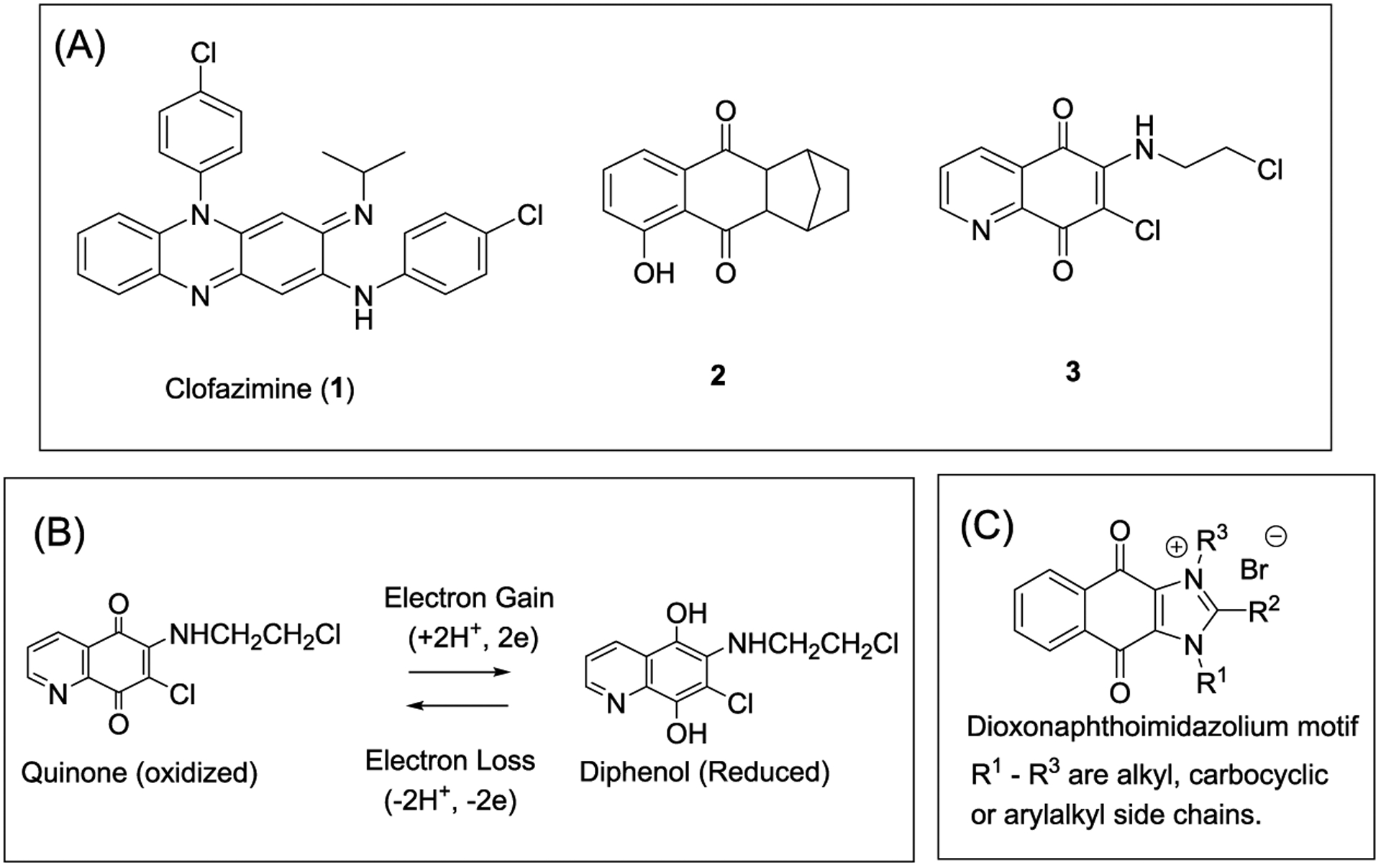

Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the causative organism of tuberculosis (TB), is one of the oldest and most successful pathogens known to infect humanity. Until the outbreak of SARS-CoV-2, more deaths were attributed to M. tuberculosis than any other infectious agent.1 The pervasiveness of TB is attributed to the ability of the organism to create defensible niches against stressful stimuli within the host environment. A major source of stress are the reactive oxygen and nitrogen species released by immune cells during the phagocytosis of M. tuberculosis.2 To this end, mycobacteria have evolved defensive strategies to oppose host-generated oxidative stress. These include radical scavengers (lipoarabinomannan, glycolipids) embedded within the cell envelope, secretory antioxidant enzymes (superoxide dismutases, catalase-peroxidases) to neutralize exogenous oxidants, cytosolic reducing buffers like mycothiol to maintain intracellular redox homeostasis, and redox stress-responsive transcription factors.2–4 The ultimate stress to the microorganism is that inflicted by antibiotic therapy, and here, contrarian views have been raised on the role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) to antibiotic lethality.5–9 One version posits that structurally and mechanistically diverse antibiotics interact with canonical targets to initiate target-specific stress responses, which alter core redox-related processes and increase ROS levels.5–7 In this interpretation, ROS are causal to antibiotic lethality with the implicit corollary that ROS-generating redox-based molecules are promising anti-TB drugs. Clofazimine (CFZ, 1, Figure 1A), which is used to treat multidrug-resistant (MDR) TB, attests to the therapeutic potential of this approach.10 The mode of action of CFZ is proposed to involve a redox cycling pathway initiated by the reduction of its quinone diimine moiety by type II NADH dehydrogenase (NDH2), the primary respiratory chain NADH:quinone oxidoreductase in mycobacteria.11,12 The hexahydroanthracenedione 2 and quinolinequinone 3 also leverage on redox cycling for antimycobacterial activity (Figure 1A).13,14 In both molecules, redox cycling of the quinone produced bactericidal levels of ROS. Evidence from 2 point to the diminished capacity of M. tuberculosis to quench elevated levels of ROS generated within cells as opposed to those generated extracellularly.13 In the case of the quinolinequinone 3, redox cycling involved reduction of the quinone by NDH2 and the release of ROS when the diphenol undergoes spontaneous reoxidation (Figure 1B).14

Figure 1.

(A) Structures of redox cycling antimycobacterial agents: clofazimine (1), hexahydroanthracenedione 2, and quinolinequinone 3. (B) Redox cycling of the quinone moiety in 3.14 Electrons are supplied by NADH for the NDH2-mediated reduction of the quinone. Reoxidation of the diphenol occurs spontaneously with electrons transferred to oxygen to form ROS. (C) Structure of the cationic amphiphilic dioxonaphthoimidazolium motif.

We have previously reported several potent N,N-disubstituted dioxonaphthoimidazoliums against Plasmodium falciparum.15 These compounds were found to generate ROS in an in vitro redox cycling assay but were not followed up in plasmodia. Here, we propose the dioxonaphthoimidazolium scaffold as a membrane-directed redox cycling mycobactericidal chemotype (Figure 1C). Our hypothesis is predicated on the localization of the cationic amphiphilic scaffold in the mycobacterial cell membrane, wherein the redox cycling quinone could potentially engage the respiratory electron transport chain to generate bactericidal levels of ROS. Cationic amphiphiles are intrinsically drawn to the lipid-rich mycobacterial cell membrane because of their lipophilic character and electrostatic attraction for the abundant negatively charged phospholipids and polyanionic surface groups on bacterial membranes.16–18 The dioxonaphthoimidazolium scaffold is the prototypical cationic amphiphile with a permanent positive charge and side chains (R1, R3) on the ring N atoms that can be modified to achieve the desired balance of lipophilicity for optimal activity. In this report, we describe lead optimization of the chemotype to yield potent and selective antimycobacterial candidates and present corroborative evidence from microbiological, biochemical, and genetic investigations to support redox cycling and the coupling of ROS generation to NDH2 as causal to the outstanding bactericidal properties of these compounds.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Chemistry.

The three rings in the dioxonaphthoimidazolium scaffold were investigated to establish their contributions to antimycobacterial activity. Modifications to the imidazolium ring were investigated in series 1–4 (Figure 2). In series 1, R2 was kept as methyl and homologation of the alkyl side chains (methyl to n-dodecyl) was explored at R1 and R3. Branching of selected R1/R3 alkyl side chains was also examined. In series 2, the alkyl side chain at R3 was replaced by a ring-based structure (cycloalkyl, benzyl, cyclohexylalkyl, morpholinyl-4-propyl, spiro[5.5]undecane) with methyl at R2 and an alkyl side chain (n-butyl to n-octyl) at R1. Next, we prepared series 3, in which the R2 methyl was replaced by ethyl while keeping R1 and R3 as n-hexyl or n-octyl. Removal of R3 from the azomethine N gave the uncharged analogues of series 4. In this series, R2 was methyl and side chains of varying lengths (methyl to n-decyl) were explored at R1. In series 5, the quinone ring was omitted from the scaffold to give benzimidazoles, and in series 6, an azomethine N was inserted into the scaffold to give dioxoimidazoquinoliniums and dioxoimidazoisoquinoliniums (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Overview of the structural motifs of compounds in series 1–6.

In all, 80 compounds were synthesized and their structures are presented in Table 1. Of these, several (4–37 in series 1, 66–70 in series 4) have been synthesized and screened for antiplasmodial activity.15 The reported synthetic pathways were employed to obtain the other compounds in series 1–4 (Scheme 1). Briefly, the reaction involved substituting the chlorine atom in 2,3-dichloronaphthalene-1,4-dione with a nucleophilic R1-amine, acylation of the amine to introduce R2, and another nucleophilic substitution at the remaining chlorine atom to install the R3 amine. The final step was cyclization under acidic conditions to give the imidazolium ring in series 1–3. As for the uncharged naphthoimidazolediones in series 4, the same sequence of reactions was followed except that the first nucleophilic displacement reaction involved ammonia.

Table 1.

Structures, cLogP Values, and Antimycobacterial Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Values of Series 1–6 Compounds on M. bovis Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG)

|

Minimum inhibitory concentration required to reduce growth by 90% compared to untreated controls. Mean (±SD) of n = 3 separate determinations. For n = 2, the value of each determination is indicated. MIC90’s of clofazimine and isoniazid (INH) were 0.40 and 3.2 μM, respectively.

cLogP is an estimate of lipophilicity, and values were determined using ChemDraw Professional Version 15.1.0.144.

Scheme 1.

aReagents and conditions: (a) R1NH2, EtOH, room temperature (RT), 1 h, 89–99%; (b) (R2CO)O, conc. H2SO4 (cat.), RT, 1 h, 55–96%; (c) R3NH2, acetonitrile (ACN), 45 °C, 1 h, 36–98%; (d) 48% HBr, EtOH/EtOAc 1:1, 45 °C, overnight, 60–98%; (e) 7N NH3 in MeOH, EtOH, 35 °C, 3 h, 85%; (f) Ac2O, conc. H2SO4 (cat.), RT, 2 h, 29%.

As for series 5, the N-substituted benzimidazoles were prepared by reacting 2-methylbenzimidazole (99) with bromoalkanes in the presence of KOH. The quaternary benzimidazolium 75 was obtained by reacting 1-n-butyl-2-methylbenzimidazole (76) with 1-bromooctane (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

aReagents and conditions: (a) AcOH, 120 °C, 5 h, 32%; (b) KOH, R1Br, 60 °C, 7 h, 54–98%; (c) C4H9Br, ACN, reflux, 47 h, 86%.

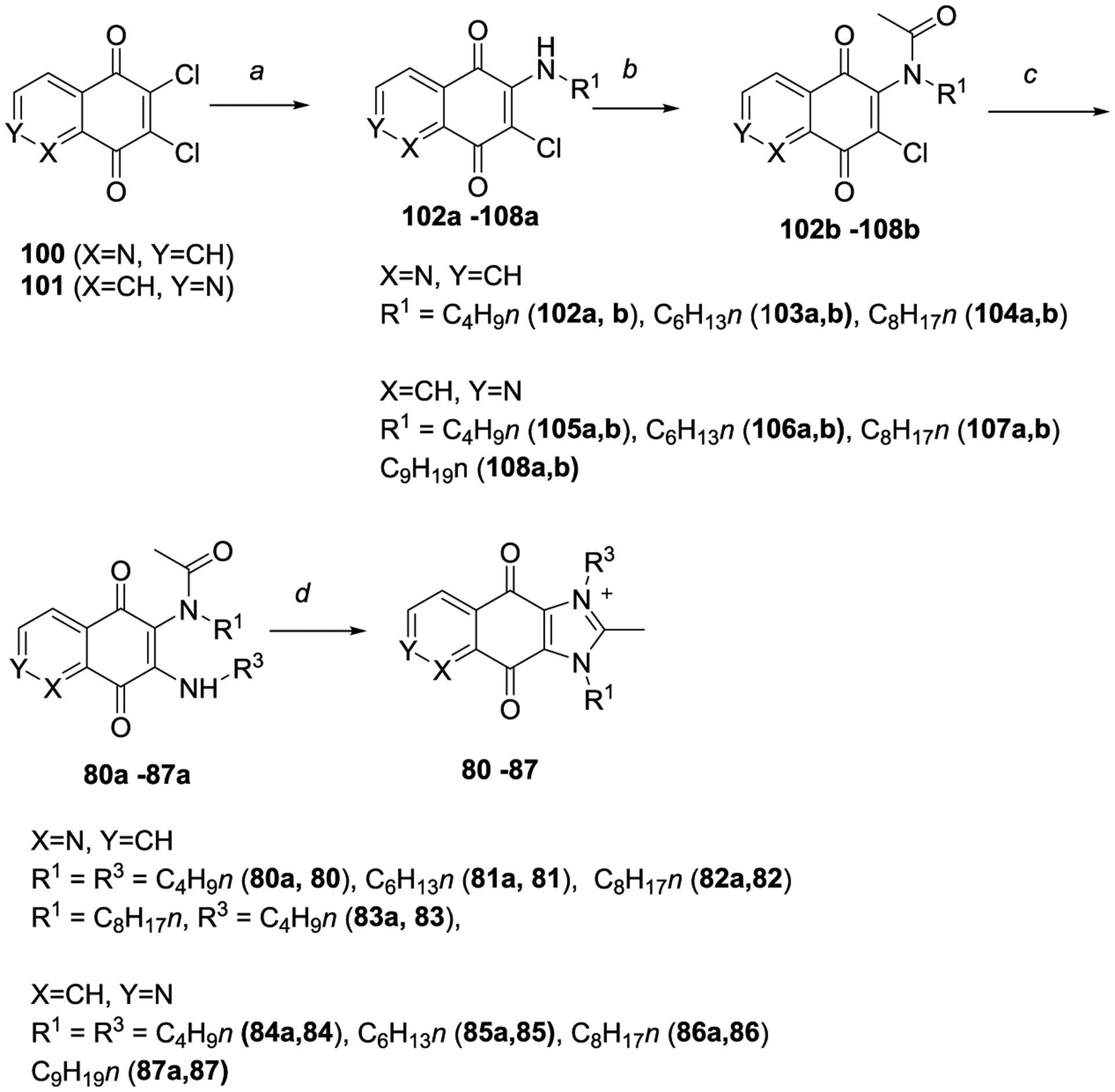

Scheme 3 outlines the synthesis of the dioxoimidazoquinoliniums 80–83 and dioxoimidazoisoquinoliniums 84–87 of series 6. Briefly, the starting diones 100 and 101 were synthesized using reported methods.19,20 They were then reacted with an R1-amine, acylated with acetic anhydride, substituted with a nucleophilic R3-amine and cyclized to afford the target compounds (80–87).

Scheme 3.

aReagents and conditions: (a) R1NH2, EtOH, RT, 1 h, 47–89%; (b) Ac2O, conc. H2SO4 (cat.), RT, 1 h, 62–98%; (c) R3NH2, ACN, 45 °C, 1 h, 49–75%; (d) 48% HBr, EtOH/EtOAc 1:1, 45 °C, overnight, 47–95%.

Antimycobacterial Activity of Dioxonaphthoimidazoliums Is Dependent on the Presence of Quinone, Positive Charge, and Lipophilic/Conformational Features of R1 and R3 Side Chains.

The synthesized compounds were screened for growth inhibition (minimum inhibitory concentration, MIC) using the broth dilution method and M. bovis BCG as test organism (Table 1).21–24 M. bovis BCG is a widely used surrogate of M. tuberculosis for activity profiling of compounds.25,26 This strain presents an attenuated tubercle bacillus and is thus closely related to M. tuberculosis. The two bacteria show 99.9% genome identity, with 97% of M. tuberculosis proteins having conserved orthologs in M. bovis BCG.25–27 The advantage of using the attenuated BCG strain is that this bacterium can be grown and tested under biosafety level 2 conditions, as opposed to biosafety level 3 conditions required for working with M. tuberculosis. Thus, for biosafety reasons and convenience, many screening and drug discovery campaigns use M. bovis BCG for hit identification and compound characterization and only progress M. bovis BCG actives to M. tuberculosis testing for confirmation of activity.25,26 We followed the same rationale in our investigations.

We first considered the structure–activity relationship of series 1, which made up two-thirds of the compound library. Only permutation of the alkyl chain length was explored in series 1, and as such, this series is well placed to provide insights into the relationship between lipophilicity and potency. Here, we found that the lipophilicities (expressed as cLogP) of series 1 ranged from −3 to 8 (1011-fold), whereas growth inhibitory MIC90’s varied from 0.2 to 40 μM (200-fold). A plot of cLogP versus pMIC90 revealed an asymmetrical inverted U-shaped curve with pronounced losses in activity at cLogP < 0 as opposed to a gradual tapering off as cLogP exceeded 5 (Figure 3). Fourteen compounds with cLogP of 1–4 had pMIC90 values > 0 (MIC90 < 1 μM). Five of these compounds (32, 34, 35, 48, 50) had pMIC90 > 0.5 (MIC90 ≤ 0.3 μM) and were arbitrarily recognized as actives, pending confirmation on M. tuberculosis H37Rv. Interestingly, cLogP’s of these actives varied within a narrower range of 0.9 to 2.1.

Figure 3.

Plot of pMIC90 versus cLogP of series 1 analogues (n = 51).

Next, the replacement of the N-alkyl side chain at R3 with a ring-based structure was explored. We noted that the n-propyl to cyclopropyl conversion in series 1 did not improve activity, but this was more likely due to the polar nature of the cyclopropyl analogues (cLogP < −1) rather than an adverse outcome of cyclization. Hence, in the design of series 2, we intentionally introduced larger-sized rings at R3 and longer n-alkyl side chains at R1 to achieve a wider lipophilicity coverage. Gratifyingly, three of the nine compounds in series 2 qualified as potential actives (MIC90 ≤ 0.3 μM). We noted that these compounds (61–63) were more lipophilic (cLogP 2.4–4.5) than the series 1 actives and, intriguingly, have in common a spiro[5.5]undecane ring at R3. This spirobicyclic ring is unusual among the other rings in having a unique three-dimensional framework, wherein the two rings are constrained to perpendicular planes. Tentatively, we ascribe the outstanding activities of these series 2 actives to the unique conformational attributes of the bicyclic ring. This would implicate different structure–activity requirements for the series 1 and 2 actives, with lipophilicity ostensibly directing activity in the di-alkyl-substituted series 1 compounds and conformational considerations predominating in the ring-based members of series 2.

Thus far, R2 in series 1 and 2 was kept as methyl. In series 3, it was replaced by ethyl while keeping the same N-alkyl substituents as those found in the actives 32 and 50. No discernible change in MIC90’s was observed in the resulting analogues (64, 65), indicating that R2 had a minimal effect on activity.

Series 4 was designed to interrogate the importance of the positive charge on the dioxonaphthoimidazolium ring. To this end, R3 was removed to give an uncharged scaffold with alkyl side chains at R1 and R2. Without the charge, the series 4 compounds were predictably more lipophilic (cLogP 2–7) and, as anticipated, less potent than the series 1 actives. Curiously, the loss in activity for most members was disproportionately large when juxtaposed against their lipophilicities, suggesting that other factors may have contributed to the striking losses in activity. A conceivable option is that the electron-withdrawing positive charge on the imidazolium N serves to activate redox cycling in the quinone. This notion would dovetail with reports that electron-withdrawing groups increase the reduction potential of quinones, hence facilitating reduction and the propensity to redox cycle.19,28 As the activity of the dioxonaphthoimidazolium chemotype is predicated on redox cycling, it follows that in the absence of charge, activity would be diminished.

In series 5, we removed the quinone ring from the scaffold to give the N-substituted benzimidazolium 75 and benzimidazoles 76–79. Without the quinone, the benzimidazolium 75 (MIC90 > 50 μM) was predictably less potent than its quinone-bearing series 1 analogue 32 (MIC90 0.26 μM). On the other hand, some benzimidazoles (76, 77) had MIC90’s (20 μM, >50 μM) that were broadly comparable to their corresponding quinone counterparts in series 4 (70, 73). It would seem that these analogues with nonactivated quinones were no better than those without the quinone altogether.

Finally, we modified the naphthoquinone (NQ) core in the scaffold by substituting a methine CH with an azomethine N to give the dioxoimidazoquinoliniums (80–83) and dioxoimidazoisoquinoliniums (84–87) of series 6. The inclusion of the electron-withdrawing azomethine N was posited to complement the charged imidazolium N and enhance activation of the redox cycling quinone. Disappointingly, neither scaffold yielded analogues that were more potent than the existing actives. Clearly, electron withdrawal by the uncharged azomethine N (a weak base) was insufficient to further activate the quinone and had in fact adversely affected activity for reasons that remain to be established.

Collectively, the modifications undertaken in series 1–6 have identified the minimum structural requirements for potent antimycobacterial activity in the dioxonaphthoimidazolium chemotype. These are the charged imidazolium N for activation of the quinone and the substituents at R1 and R3, which presumably defined the lipophilicity limits for access into the mycobacterial membrane. Lipophilicity considerations dominated the optimal alkyl chain lengths but were ostensibly less important in ring-bearing side chains where conformational features of the ring appear to take precedent.

Antimycobacterial Profiles of Selected Dioxonaphthoimidazolium Actives.

Phenotypic screening of series 1–6 led to a shortlist of eight actives (32, 34, 35, 48, 50, 61–63) with MIC90 BCG values ≤ 0.3 μM. The growth inhibitory activities of these compounds were reconfirmed on the pathogenic organism M. tuberculosis H37Rv (Table 2). Here, we found MICs across the two species to be comparable, except for 34 and 35, which were 10- to 20-fold less potent against M. tuberculosis. As both compounds are structurally related to 32, we excluded them from further profiling without additional follow-up. Encouragingly, the remaining compounds were bactericidal against M. bovis BCG and M. tuberculosis H37Rv at concentrations (MBC99.9) ≤ 5× MIC90. When evaluated for cytotoxicity against mammalian Vero cells, selective indices of these actives qualified them as hit compounds (SI > 10),29 with 32, 48, and 61 displaying the best selectivities (SI > 25).

Table 2.

Profiling of Antimycobacterial Activities of Actives Identified Against M. bovis BCG (32, 34, 35, 48, 50, 61–63)

| no. | M. tuberculosis H37Rv (μM)a | M. bovis BCG (μM)a |

M. tuberculosis H37Rv MBC99.9 (μM)b |

M. bovis BCG MBC99.9 (μM)b |

Vero IC50 (μM)c | SId | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC50 | MIC90 | |||||

| 32 | 0.82 (±0.13) | 1.5 (±0.1) | 0.15 (±0.05) | 0.26 (±0.08) | 6.3 (6.3, 6.3) | 0.64 (0.64, 0.64) | 24 (±1) | 29 |

| 34 | 4.0 (4.0, 4.0) | 6.0 (6.0, 6.0) | 0.18 (±0.10) | 0.30 (±0.10) | not done | not done | not done | not done |

| 35 | 2.0 (2.0, 2.0) | 3.0 (3.0, 3.0) | 0.14 (±0.04) | 0.25 (±0.10) | not done | not done | not done | not done |

| 48 | 0.77 (±0.25) | 1.2 (±0.7) | 0.16 (±0.03) | 0.27 (±0.09) | 6.3 (6.3, 6.3) | 0.64 (0.64, 0.64) | 20 (±3) | 26 |

| 50 | 0.67 (±0.21) | 1.5 (±0.2) | 0.11 (±0.07) | 0.22 (±0.12) | 6.3 (6.3, 6.3) | 0.64 (0.64, 0.64) | 14 (±4) | 21 |

| 61 | 0.28 (±0.05) | 0.53 (±0.10) | 0.13 (±0.02) | 0.28 (±0.12) | 1.6 (1.6, 1.6) | 1.3 (1.3,1.3) | 15 (±2) | 54 |

| 62 | 0.30 (0.3, 0.3) | 0.40 (0.4, 0.4) | 0.08 (±0.03) | 0.15 (±0.06) | 1.6 (1.6, 1.6) | 0.20 (0.20, 0.20) | 6.3 (±0.1) | 21 |

| 63 | 0.30 (0.3, 0.3) | 0.40 (0.4, 0.4) | 0.11 (±0.04) | 0.20 (±0.09) | 1.2 (0.8, 1.6) | 0.20 (0.20, 0.20) | 5.0 (±0.4) | 17 |

Minimum inhibitory concentration required to reduce growth by 50% (MIC50) or 90% (MIC90) compared to untreated controls. MIC50 Mtb and MIC90 Mtb values: (i) INH = 1.6, 3.2 μM; (ii) CFZ = 0.2, 0.8 μM; MIC50 BCG and MIC90 BCG values: (i) INH = 1.6, 3.2 μM; (ii) CFZ = 0.2, 0.4 μM.

Minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) required to kill 99.9% of mycobacteria.

Concentration required to reduce growth of Vero (African Green Monkey kidney epithelial cells) by 50% compared to untreated controls.

Selectivity index = IC50 Vero/MIC50 Mtb. MIC, MBC99.9, and IC50 values are reported as mean (±SD) of n = 3 separate determinations or mean of two separate determinations (values given).

Having established that the actives were bactericidal, we proceeded to determine if their bactericidal effects on M. bovis BCG were time-dependent. To this end, the time-kill profiles of two actives 32 and 48 were monitored over 28 days at 4× MIC90BCG. As shown in Figure 4A, both compounds induced a steady reduction in colony-forming unit (CFU) count, reducing the viability of the cultures 100 000-fold over 14 days before leveling off and settling to an apparently suppressed steady state that continued until day 28. In comparison, the killing kinetics of isoniazid was characterized by an initial fall in colony count preceded by a rebound at Day 7. By Day 28, colony growth was in fact comparable to the drug-free cultures, consistent with the emergence of isoniazid-resistant mutants.30 When the time-kill profile was repeated at different concentrations of 32 (Figure 4B), the highest test concentration (8× MIC90) successfully reduced growth such that CFUs were not detected from day 21 onward. Thus, 32 may prevent the emergence of resistant mycobacteria.

Figure 4.

Mid-log-phase M. bovis BCG cultures diluted at OD600 0.1 were treated with (A) 32 and 48 at 4× MIC90 and (B) 32 at 2×, 4×, and 8× MIC90 at 37 °C for 28 days with shaking. At indicated time points, culture aliquots were plated out for CFU counting. Isoniazid (INH) at 4× MIC90 (12.8 μM) was included as control. (C) Bactericidal activities of 32 and 48 under oxygen-deprived conditions (Wayne model). WCC90, WCC99, and WCC99.9 are concentrations required to reduce CFU by 10×, 100×, and 1000×, respectively, compared to drug-free (DF) control at time zero (D0). (D) Bactericidal activities of 32 and 48 under nutrient-deprived conditions (Loebel model). LCC90, LCC99, and LCC99.9 are concentrations required to reduce CFU by 10×, 100× and 1000×, respectively, compared to drug-free (DF) control at time zero (D0). Isoniazid (INH) and rifampicin (RIF) were employed as negative and positive controls in (C) and (D), respectively. DF D5 and DF D7 are the CFU counts on days 5 and 7 corresponding to the end of drug treatments for (C) and (D), respectively. At least two biological repeats were carried out for each experiment. Figures depicted in (A)–(D) are from representative experiments.

The in vitro antimycobacterial activities of hit compounds identified by phenotypic screening are susceptible to artifacts caused by the growth media.31,32 Of particular concern is glycerol, a favored carbon source of M. tuberculosis and M. bovis BCG in laboratory growth media. Nearly 10% of antimycobacterial hits display glycerol-dependent activity due to their ability to dysregulate glycerol metabolism and form metabolites that are toxic to mycobacteria.32 To exclude the confounding effects of glycerol, MICBCG determinations of actives 32, 34, 35, 48, 50, and 61 were repeated in glycerol-free 7H9 media and compared to values obtained in standard (glycerol-containing) 7H9 media. Gratifyingly, MIC values did not differ by more than 2-fold, signaling the absence of glycerol dependency (Figure S2 and Table S3).

Next, we evaluated 32 and 48 against nongrowing phenotypically drug-tolerant organisms in cultures grown under oxygen-deprived (Wayne model) and nutrient-deprived (Loebel model) conditions. On the Wayne model, both compounds reduced viability by only 10-fold, even at the highest concentrations (40× MIC90, 12 μM) (Figure 4C). Clearly, oxygen deprivation adversely affected the bactericidal activities of 32 and 48. By contrast, both compounds exhibited robust activity against nutrient-deprived M. tuberculosis (Figure 4D). Notably, 32 and 48 at 40× MIC90 (64 μM) substantially reduced CFUs to levels equivalent to or below the detection limit. The pronounced bactericidal effect of these compounds against nutrient-starved mycobacteria is noteworthy considering that most anti-TB drugs that are bactericidal against growing bacteria lose this property against the physiological form of the bacillus.33

Dioxonaphthoimidazolium Actives 32, 48, and 61 Did Not Permeabilize or Depolarize Mycobacterial Cell Membrane or Upregulate Cell Envelope Stress Reporter Genes.

Disruptions to the structural and functional integrity of the mycobacterial cell membrane by cationic amphiphilic antimycobacterial agents is well precedented.22–24,34–36 These perturbations trigger multiple effects on the cell membrane such as impaired permeability, loss of membrane potential, induction of cell membrane stress reporter genes, and aberrations in membrane protein function. To determine if the cationic amphiphilic dioxonaphthoimidazolium is a membrane disruptor, we monitored the time-dependent uptake of DiOC2 (to detect membrane depolarization) and fluorescent probes SYTO-9/propidium iodide (PI) (to detect membrane permeabilization) by M. bovis BCG cultures treated with actives 32 and 48 (Figure 5A,B). Neither compound induced depolarizing or permeabilizing effects after 8 h of exposure. At longer time points, some indications of permeabilization and depolarization were observed, but these were arguably linked to the onset of cell death (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

(A) Membrane depolarization of M. bovis BCG cultures by 32 and 48 at 4× MIC90 (1.2 μM) over 48 h was investigated using DiOC2, which emits red fluorescence in polarized membranes and green fluorescence in depolarized membranes. The red/green fluorescence ratio is correlated to membrane potential and decreases when membranes are depolarized. Compounds 32 and 48 significantly decreased the ratio at 48 and 24 h, respectively, but this coincided with the onset of cell death, as seen from (C), which monitors CFU over time in cultures treated with test compounds (4× MIC90). RIF and carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP) were negative and positive controls, respectively. The antibacterial activity of RIF is due to the inhibition of DNA-dependent RNA polymerase. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 compared to drug-free (DF) sample at each time point, Student’s t-test, GraphPad Prism Ver. 8.4.3. (B) Membrane permeabilization was investigated with fluorescent probes SYTO-9 (green fluorescence, taken up by all cells) and propidium iodide (PI, red fluorescence, taken up by cells with compromised membranes). The green/red ratios of treated cultures were normalized against values obtained from untreated cultures (no permeabilization) and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-treated cultures (complete permeabilization) to give % permeabilization. RIF was employed as negative control. Permeabilization of treated cultures was observed at 24 h (32 only) and 48 h and attributed to the onset of cell death, as evident from (C). (D) piniBAC promoter activity (RFU/OD600) in recombinant M. bovis BCG-piniBAC red fluorescent protein (RFP) treated with 32, 48, and 61 over 24 h at concentrations of 0.4–25 μM. Normalized fluorescence readings (RFU/OD600) were recorded to account for changes in cell number during incubation. An increase in the normalized signal indicates induction of the gene cluster. INH is the positive control and induces promoter activity at 1.6 μM (0.5× MIC90). Experiments in (A–D) were performed in biological replicates, and data shown are from representative experiments.

Next, we probed the mycobacterial piniBAC promoter, which is transcriptionally upregulated when the cell envelope is subjected to stressful stimuli elicited by cell wall inhibitors and membrane targeting agents.37 To verify induction of the promoter, a strain of M. bovis BCG in which red fluorescent protein (RFP) expression was controlled by the piniBAC promoter was employed. As seen from Figure 5D, there was no increase in fluorescence from cultures treated with the actives (32, 48, 61), even at the highest concentration (~100× MIC90), signifying that these compounds did not induce cell envelope stress. Isoniazid, which disrupts mycobacterial cell wall biosynthesis, duly increased piniBAC promoter activity as seen from the elevated fluorescent signals.

Collectively, the fluorescence-based and genetic reporter assays corroborate the absence of stress-inducing membrane disruptive effects by the dioxonaphthoimidazolium actives. We found this puzzling given the cationic amphiphilic character of the scaffold but noted that several quinones such as menaquinone and vitamin K have been reported to be membrane stabilizers.38,39 Thus, we reasoned that if the quinone in the dioxonaphthoimidazolium ring is membrane-stabilizing, it could negate the anticipated perturbative effects of the cationic amphiphilic scaffold, giving rise to the present observations. On a related note, CFZ is also a cationic amphiphile but has pronounced membrane disruptive effects.40–42 Two factors could account for this intriguing difference. First, redox cycling in CFZ involves a quinone diimine, which has not been associated with membrane stabilization, and second, in view of its exceptional lipophilicity (cLogP 7.5), it is conceivable that CFZ accumulates in membranes to levels that could trigger promiscuous nonspecific effects.43 Related to its lipophilicity is the poor water solubility of CFZ, a factor that has hindered investigations into its biological activity.11 Hence, in spite of its suitability as a redox cycling comparator to our compounds, we did not employ CFZ in this capacity for our investigations.

Dioxonaphthoimidazolium Actives 32, 48, and 61 Generated Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in M. bovis BCG.

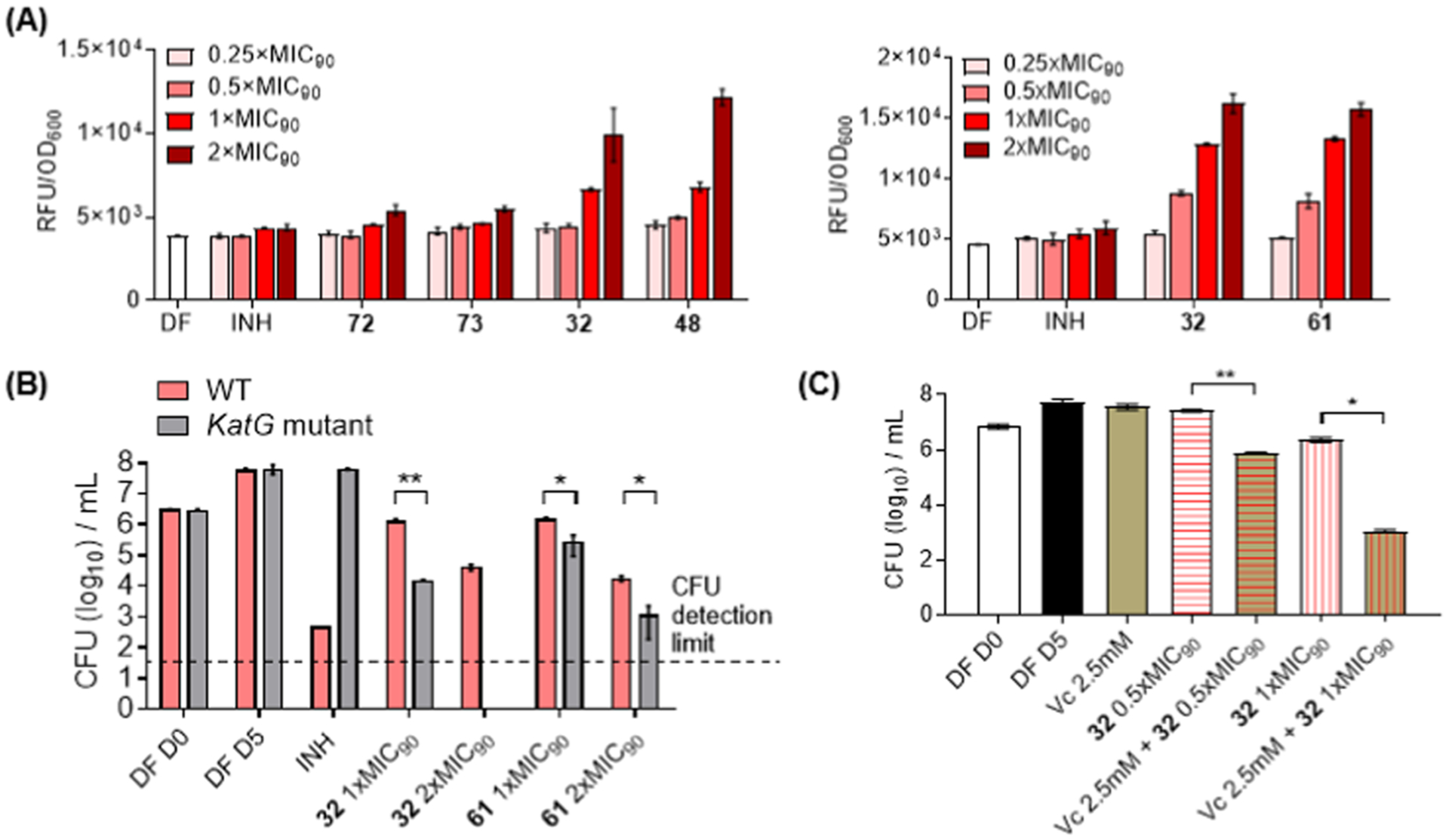

In an earlier investigation, we verified that several series 1 analogues generated hydrogen peroxide via redox cycling in an in vitro horseradish peroxidase-phenol red assay.15 To determine if this phenomenon also occurs in mycobacterial cultures, we monitored ROS production using CellROX Green Reagent (Invitrogen). Briefly, the reagent contains a cell permeant dye, which is converted to a strongly fluorescent species when oxidized by ROS in the cellular milieu. The compounds tested were the actives (32, 48, 61), naphthoquinone (positive control), and isoniazid (negative control). Also included were two uncharged series 4 compounds (72, 73), which had weak antimycobacterial activity. First, we asked if the test compounds induced dose-dependent ROS production. This was duly observed for actives 32, 48 (Figure 6A), and 61 (Figure 6D) but not 72 and 73 at low doses of ≤1× MIC90 (Figure 6A). However, when tested at a higher dose of 2× MIC90, both 72 and 73 increased ROS levels but not to the levels induced by the actives at comparable doses. Next, we queried if ROS levels were transient or persisted over time. A short-lived elevation of ROS levels would not contribute to bactericidal activity as was noted for some antimycobactericidal imidazoles where ROS levels rapidly dissipated by 24 h.44 To this end, we monitored ROS levels in cultures treated with test compounds (2× MIC90) for up to 24 h (Figure 6D,E). Gratifyingly, ROS levels were sustained over time in all test cultures, hence affirming the longevity of the phenomenon and the likelihood of its contribution to the bactericidal properties of the actives.

Figure 6.

(A) Detection of ROS levels in M. bovis BCG cultures treated with varying concentrations of 32, 48, 72, and 73 after 90 min of incubation. (B) Detection of ROS levels over time (30 min to 24 h) in the presence of 32, 48, 72, and 73 at 2× MIC90. (C) Concurrent CFU monitoring of cultures treated with 32, 48, 72, and 73 (2× MIC90) over 24 h. (D–F) Same as (A–C) but with test compounds 32 and 61. ROS levels were detected using CellROX Green Reagent (Invitrogen). The fluorescent signal from the dye (GFU) was normalized against OD600 of treated cultures to account for variations in cell number. DF is drug-free control. Isoniazid (INH) and naphthoquinone (NQ) were negative and positive controls, respectively. MIC90 BCG of NQ was 50 μM. At least two biological repeats were carried out for each experiment. Figures depicted in (A)–(F) are from representative experiments.

Dioxonaphthoimidazolium Actives Induced the Oxidative Stress-Inducible Promoter pfurA in M. bovis BCG.

FurA is a mycobacterial redox-sensing transcriptional repressor, which negatively regulates its own transcription by binding to an oxidative stress-responsive promoter (pfurA) located upstream of the fur coding sequence.45 Binding of FurA to pfurA displaces mRNA polymerase from its site of action and represses furA transcription. Under conditions of oxidative stress, the FurA protein undergoes a conformational change, which reduces its binding affinity to pf urA. Consequently, pfurA is activated and transcriptional competency is restored.46,47 Here, we monitored the fluorescence emitted by a strain of M. bovis BCG, in which RFP expression is controlled by pfurA. An increase in the fluorescent signal is indicative of an activated pfurA, and by extrapolation, the presence of oxidative stress. As shown in Figure 7A,B, the actives 32, 48, and 61 at 0.5× to 2× MIC90 induced dose-dependent increases in fluorescence, indicating activation of pfurA. This trend was less evident in cultures treated with the less active analogues 72 and 73, although some increases were observed at the highest dose of 2× MIC90. Thus, perturbation of mycobacterial redox equilibrium by the actives was of sufficient magnitude to activate an oxidative stress regulon in mycobacteria.

Figure 7.

(A) pfurA Promoter activity in a recombinant strain of M. bovis BCG-pfurA-RFP (mid-log phase, inoculum at OD600 = 0.2) treated with test compounds (32, 48, 61, 72, and 73) over a range of concentrations for 24 h. Fluorescent signal (RFP) was normalized against OD600 of treated cultures to account for variations in cell number. DF and INH were employed as drug-free and negative controls. (B) Colony formation by wild-type M. bovis BCG and a katG loss-of-function mutant strain in the presence of test compounds (32, 61) at 1× and 2× MIC90. The control INH was inactive against the mutant strain. (C) Colony formation by M. bovis BCG in the presence of vitamin C (2.5 mM), 32 (0.5×, 1× MIC90), and combinations of vitamin C and 32. For (B) and (C), experiments were carried out in catalase-free 7H9 broth and aliquots withdrawn from the liquid media for CFU counting. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01, Student’s t-test (GraphPad Prism, Ver 8.4.3). DF D0 and DF D5 were drug-free controls monitored on day 0 and day 5 of incubation, corresponding to start and end of drug exposure. At least two biological repeats were carried out for each experiment. Figures depicted in (A)–(C) are from representative experiments.

Dioxonaphthoimidazolium Actives Exhibit Greater Growth Inhibitory Activity against a katG Loss-of-Function Mutant Strain of M. bovis BCG.

The catalase peroxidase KatG protects M. tuberculosis against ROS in activated macrophages.48 It follows that mycobacteria lacking a functional KatG would be more susceptible to oxidative stress and hence display greater sensitivity to ROS-generating agents compared to the parental (wild-type) strain. To generate a katG loss-of-function mutant strain of M. bovis BCG, we selected spontaneously resistant mutants on agar containing isoniazid, a prodrug that requires redox activation by KatG.49 One resistant strain that was subjected to whole genome sequencing revealed a CG deletion at 633–634 bp of the katG coding sequence, resulting in a truncated aberrant protein product. The mutation in katG was verified by targeted sequencing with reported primers,50 and the expected phenotype of the mutation was confirmed by MIC determinations on isoniazid (Figure S3). We observed that 32 and 48 had lower (2- to 4-fold) growth inhibitory MICs against the mutant strain, indicating enhanced potency against the katG loss-of-function mutant (Figure S3). Curiously, a shift to lower MICs was not evident for 61 in liquid media but was observed when aliquots of the growth media were plated out onto solid agar for CFU enumeration (Figure 7B). In contrast, the sensitivity of the mutant to 32 was evident in both liquid and solid media (Figure 7B).

Growth Inhibitory Activity of 32 Is Augmented by Vitamin C Supplementation but Unaffected by the Addition of Antioxidants.

The mycobactericidal activity of vitamin C has been ascribed to ROS production linked to iron-dependent Fenton/Haber–Weiss reactions.30,51 Here, we asked if augmenting ROS levels by treating M. bovis BCG to a combination of a dioxonaphthoimidazolium active and vitamin C would increase the susceptibility of the organism to cell death. To this end, the bactericidal activity of 32 (0.5× and 1× MIC90) was determined in the presence of a nonlethal concentration (2.5 mM) of vitamin C. As shown in Figure 7C, significant reductions in CFU counts were encountered when vitamin C was added to 32, particularly when added to 32 at its MIC90 where Log10 CFU counts were nearly halved. Thus, the addition of vitamin C to 32-treated cultures led to greater bactericidal activity. The implicit corollary was that losses in activity would be incurred if ROS levels were reduced, and this led us to examine the growth inhibitory MICBCG of 32 in the presence of three antioxidants, N-acetylcysteine, 2,2′,6,6′-tetramethylpiperidinyl-1-oxyl (TEMPO), and thiourea. Disappointingly, the antioxidants did not diminish the growth inhibitory potency of 32 (Figure S5). However, antioxidant effects have been noted to be inconsistent. For instance, antioxidants failed to rescue M. tuberculosis from the inhibitory effects of ROS-generating imidazoles44 but successfully reversed the bactericidal effects of clofazimine on M. smegmatis.11 Factors like the intrinsic reactivity of the antioxidant, its lipophilicity which would determine access into mycobacteria, and experimental conditions may conceivably account for the contrasting outcomes.

Dioxonaphthoimidazolium 32 and Isoniazid Display a Synergistic Interaction against M. tuberculosis H37Rv.

The potentiating effects of vitamin C on the bactericidal activity of 32 prompted us to ask if there were beneficial interactions between 32 and other antimycobacterial agents. To test this possibility, we carried out a checkerboard assay to investigate the interactions of 32 with several anti-TB agents selected to reflect a broad spectrum of mechanistic targets (Table 3). In all, only one synergistic interaction was found, namely, 32 and isoniazid, while the other combinations were indifferent.

Table 3.

Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Indices (FICI) of Drug Combinations with 32 as Determined on M. tuberculosis H37Rv Cultures

| Combination (Drug + 32) | primary antimycobacterial target of drug52 | FICIa |

|---|---|---|

| isoniazid + 32 | NADH-dependent enoyl acyl carrier protein reductase (InhA) | 0.31 |

| rifampicin + 32 | DNA-dependent RNA polymerase | 0.75 |

| bedaquiline + 32 | ATP synthase | 0.75 |

| clofazimine + 32 | NDH2 | 0.75 |

| kanamycin + 32 | 30S ribosomal subunit | 1 |

| moxifloxacin + 32 | DNA gyrase | >1 |

| SQ109 + 32 | MmpL3 | 0.63 |

Synergy between 32 and isoniazid could be explained by considering the role of katG, which encodes the enzyme required to convert isoniazid (a prodrug) to its bioactive form.49 Briefly, KatG converts isoniazid to a reactive acyl radical, which then reacts with NAD to form covalent isoniazid–NADH adducts. These adducts inhibit the enoyl acyl carrier protein reductase InhA, which is required for the synthesis of mycolic acids, an essential component of the mycobacterial cell wall. katG expression is regulated by furA, and the gene is located downstream of furA, and co-transcribed with it.45,46,55 Thus, both genes represent an operon, which is negatively regulated by the transcriptional repressor FurA.55 Both furA and katG are induced by oxidative stress, and as we have shown that 32 activated transcription from the pfurA promoter through its oxidant effects, katG expression should also be upregulated in the presence of 32. Hence, the observed synergy is underpinned by the oxidant properties of 32, which primes the conversion of isoniazid to a reactive radical species, hence augmenting its disruptive effects on cell wall biosynthesis.

No Spontaneous Resistant Mutants Could Be Raised in Cultures of M. tuberculosis H37Rv Treated with the Dioxonaphthoimidazolium Actives 32 and 48.

ROS disrupt cellular homeostasis by perturbing multiple targets56 and as such, the ability of bacteria to acquire resistance to agents that generate ROS may be limited. To verify this notion, 3 × 108 M. tuberculosis H37Rv cells were plated on complete Middlebrook 7H10 agar containing 32 or 48 at concentrations ranging from 1× to 8× MIC90 and incubated for 8 weeks. At the end of 8 weeks, no resistant colonies were isolated, confirming the low spontaneous mutation frequencies (<3 × 10−9/CFU) of 32 and 48.

Redox Cycling of 32 in Mycobacteria Involved the Respiratory Chain Enzyme Type II NADH Dehydrogenase (NDH2).

Thus far, we have shown that the bactericidal activity of the dioxonapthoimidazolium actives is causally linked to ROS generation by the activated quinone moiety. This prompted the question of whether the reduction of the quinone is dependent on an intracellular redox cycling pathway that relies on electron flow in the mycobacterial respiratory chain, as proposed for clofazimine and the quinolinequinone 3.11,14 Redox cycling would then require the quinone to be reduced by an electron donor derived from carbon catabolism (NADH, malate, succinate) in a reaction catalyzed by membrane-bound primary dehydrogenases. In the case of CFZ and 3, the reduction was catalyzed by NDH2—the primary entry point for electrons from central metabolism to the electron transport chain—followed by nonenzymatic reoxidation by O2 and ROS production.11,14 To ascertain if NDH2 is involved in the redox cycling of 32 in a similar capacity, we first determined the ability of 32 to stimulate NADH oxidation in inverted membrane vesicles (IMVs) prepared from M. smegmatis. Compound 32 readily activated NADH oxidation, with an effective concentration for 50% stimulation (EC50) of ~250 nM (Figure 8A). To determine if this was due to a direct interaction with NDH2, other respiratory enzymes were inhibited using cyanide (Figure 8A). Compound 32 retained the ability to stimulate NADH oxidation, consistent with other NDH2 activators clofazimine and 3.11,14 Next, we tested the ability of 32 to activate NADH oxidation in IMVs that overexpressed the M. tuberculosis NDH2 enzyme, analogous to experiments with 3.14 There was indeed an increase in NADH oxidation (~4.7-fold) relative to the parental strain (Figure 8B), suggesting that the M. tuberculosis NDH2 enzyme is specifically activated by 32. As the activation of NDH2 by 32 would generate ROS via reduction of oxygen, we tested the ability of 32 (1 μM) to increase oxygen consumption and generate hydrogen peroxide. Gratifyingly, increases in both oxygen consumption (~7-fold) and hydrogen peroxide production (~4-fold) were observed (Figure 8C), suggesting that electrons transferred to 32 via NDH2 were at least partially accepted by oxygen. Next, we tested the specificity of 32 for NDH2 by comparing the stimulation of NADH oxidation to that of malate oxidation. As shown in Figure 8D, 32 induced higher levels of oxygen consumption (~1.8-fold) in IMVs energized by NADH compared to malate. Compound 32 performed poorly as a protonophore, showing only moderate rates of pH gradient dissipation at 1 and 2 μM (Figure 8E). The IMVs used in these experiments were leaky, as indicated by the lack of stimulation of oxygen consumption by CCCP (Figure 8E), which in turn shows that stimulation of oxygen consumption by 32 is independent of the proton motive force. Overall, these experiments demonstrate that the formation of ROS by 32 in mycobacteria is dependent on its reduction by NDH2.

Figure 8.

(A) NADH oxidation of IMVs of M. smegmatis mc2155 in the presence of varying concentrations of 32 with or without cyanide (KCN, 20 mM). (B) NADH oxidation of IMVs derived from M. smegmatis mc24517 or mc24517 overexpressing M. tuberculosis NDH2 (pYUB-Ndh) at different concentrations of 32. LOD: Limit of detection. (C) Simultaneous monitoring of oxygen consumption and hydrogen peroxide production rates by M. smegmatis mc2155 IMVs, treated with either 32 or a vehicle control. (D) Oxygen consumption rates of M. smegmatis mc2155 IMVs treated with the indicated energy sources (NADH, malate) at varying concentrations of 32. The generation of a transmembrane gradient was also followed in this experiment (Figure S6). (E) Simultaneous measurements of oxygen consumption and transmembrane pH gradient generation in M. smegmatis IMVs derived from the parental strain mc24517 and NDH2 overexpressing strain pYUB-Ndh. Quenching of acridine orange (AO) was initiated by adding 0.5 mM NADH at the time indicated with an asterisk. Compound 32 and CCCP were added as indicated by gray vertical lines. Error bars in (A–C) represent standard deviation from triplicate measurements. Results in (D, E) are representative of triplicate measurements.

Physicochemical and Pharmacokinetic (PK) Assessment of Dioxonaphthoimidazoliums 32 and 61.

The physicochemical and in vivo mice pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters of 32 and 61 were determined (Table S4). In keeping with their charged states, both compounds displayed outstanding aqueous solubilities (~118 μM, pH 7.4) and poor parallel artificial membrane permeability assay (PAMPA) effective permeabilities (Pe ~ 10−6 cm/s). The validity of the Pe values was, however, in question because of poor analyte recoveries (~30%) from both donor and acceptor compartments, in spite of our effort to reduce nonspecific adsorption to the plastic surfaces of the plates. We attributed the poor recoveries to the retention of the compounds in the lipid layer separating the two compartments, in accordance with the amphiphilic nature of these compounds.

Both 32 and 61 were reasonably stable to metabolic degradation by rat microsomes with half-lives of 20–23 min. They were also not mutagenic on the mini-Ames test. The in vivo PK of 32 and 61 were determined in mice dosed at 1 mg/kg (intravenous, IV) or 50 mg/kg (oral). Here, we found poor oral bioavailability (F) of 1–2% for both compounds, extensive distribution into tissues as seen from the large volumes of distribution (27–35 L/kg), moderate rates of clearance (38–55 mL/(min kg)), and relatively long half-lives (7–10 h). The charged state of the compounds is the main factor accounting for the observed pharmacokinetic profiles.57

CONCLUSIONS

The investigations described in this report were designed to address two specific objectives: first, to establish that calibrated modification of the dioxonaphthoimidazolium scaffold would yield potent and selective antimycobacterial lead compounds, and second, to provide granular evidence corroborating ROS generation and interception of the mycobacterial respiratory chain as pivotal to the bactericidal activity of these compounds.

The first objective was successfully fulfilled with the identification of several dioxonaphthoimidazoliums (32, 48, 61) as potent bactericidal agents against M. tuberculosis H37Rv. Bactericidal activity was characterized by the eradication of nutrient-starved phenotypically resistant nongrowing bacteria in the Loebel model of dormancy and prolonged suppression of colony formation after a single exposure, properties that suggest that these actives could potentially hinder the emergence of resistant organisms. The minimal structural requirements for maximal potency were the quinone, positive charge imparted by the imidazolium N, and specific features associated with the N-substituted side chains R1 and R3. Unusually, the quinone is a necessary but not sufficient requirement for potent activity. Potent activity was manifested only when the quinone is activated by the electron-withdrawing imidazolium N. Hence, in the absence of a charged scaffold as exemplified by the naphthoimidazolediones of series 4, growth inhibitory activity was significantly diminished. The role of N-substituted side chains is more nuanced. The lengths of the alkyl R1 and R3 side chains defined the optimal lipophilicity for activity, which in series 1 corresponded to a relatively narrow cLogP range (0.9–2.1). This level of lipophilicity is presumably required for the positively charged compounds to gain access into the mycobacterial cell membrane. It would explain why series 1 compounds with cLogP’s that were out of range displayed weak to moderate activity even though they possess the core features for activity. A notable deviation from this lipophilicity–activity correlate is seen in the spirobicyclic actives of series 2. This anomaly may allude to alternative interactions that are not solely driven by lipophilicity but dependent on the conformational features of the side chains. Notwithstanding the attractive bactericidal profiles of several naphthoimidazolium actives, the translational potential of these compounds has yet to be verified. Notably, in vivo efficacy has not been assessed in an acute TB mouse model and preliminary toxicity profiles are lacking. When these issues are addressed in future work, caution should be exercised in interpreting the results as some actives have been shown to have suboptimal pharmacokinetic profiles.

With regard to the second objective, we have provided substantial evidence to support a redox-driven bactericidal mode of action that is reliant on electron flow in the mycobacterial respiratory chain. Specifically, we have identified a pivotal role for the respiratory enzyme NDH2 in promoting redox cycling of the dioxonaphthoimidazolium actives. The reciprocal requirement of the positively charged scaffold for both activities that was observed early in our investigations alluded to a correlation between potency and ROS generation. This association was strengthened by the robust activation of the redox-sensing mycobacterial transcription factor pfurA and failure to raise M. tuberculosis mutants. The fact the potency of actives was enhanced by supplementation with vitamin C (which produces ROS) and in a katG loss of function mutant strain further vindicates our hypothesis. Finally, the involvement of NDH2 was demonstrated by the ability of 32 to stimulate NADH oxidation and oxygen consumption in M. smegmatis-derived IMVs, even in the presence of cyanide (a respiratory chain inhibitor) as well as the significantly elevated rates of NADH oxidation in IMVs overexpressing the M. tuberculosis NDH2 enzyme. In this regard, the mode of action of this chemotype bears many similarities to CFZ and the quinolinequinone 3. However, the dioxonaphthoimidazolium actives are distinguished by their superior potencies (compared to 3, MIC90 Mtb 8 μM),14 outstanding water solubilities (unlike CFZ), and the absence of membrane perturbative effects (in contrast to CFZ). The leverage afforded by these attractive attributes even when juxtaposed against their limitations justify continued interest in this scaffold as potential leads for antimycobacterial drug discovery.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

General Chemistry.

Commercially available reagents of synthetic grade (or better) were used without further purification. Air-sensitive experiments were carried out under N2 atmosphere in oven-dried glassware fitted with rubber septa. Reactions were monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on aluminum-backed sheets coated with silica gel (Merck 60 F254, 250 μm thickness). Compounds were purified by column chromatography on silica gel 60 (230–400 mesh, Merck), and compounds were detected on TLC sheets by ultraviolet light or with appropriate stains (phosphomolybdic acid (PMA), potassium permanganate). 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3, CD3OD-d4, DMSO-d6, or acetone-d6 on a Bruker Avance 300, 400, or 500 MHz spectrometer (Bruker Corp., MS). Chemical shifts were reported in ppm on the δ scale using residual protiosolvent signals (1H NMR: CDCl3 δ 7.26, DMSO-d6 δ 2.50, CD3OD-d4 δ 3.31, acetone-d6 δ 2.50; 13C NMR: CDCl3 δ 77.00, DMSO-d6 δ 39.50, CD3OD-d4 δ 49.00, acetone-d6 δ 206.68) as internal references. Coupling constants (J) were reported in Hz, and splitting patterns as singlet (s), broad singlet (br s), doublet (d), doublet of doublets (dd), triplet (t), triplet of doublets (td), quartet (q), quintet (quint), sextet (sext), or multiplet (m). Nominal mass spectra were captured on an LCQ Fleet Ion Trap LC-MS system (Thermo Scientific) by ESI or EI, run in either positive or negative ionization mode. High-resolution mass spectra were recorded on a Bruker MicroTOF-QII mass spectrometer (Bruker Corp., MA) by ESI (positive or negative ionization mode). Purities of final compounds were analyzed by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Shimadzu Nexera SR, Japan) and found to be >95% pure.

General Procedure for the Synthesis of 3-Alkylamino-2-chloro-1,4-naphthoquinones (88a–94a, 97).

2,3-Dichloro-1,4-naphthoqui-none was suspended in 5 mL of ethanol. The corresponding amine (3 equiv) was added with stirring, and the resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h. Upon completion, the reaction mixture was diluted with 10 mL of dichloromethane (DCM) and loaded onto silica gel for purification by column chromatography. Elution with DCM afforded the desired products as red solids. This procedure is referred to as Procedure A in the Supporting Information (SI).

General Procedure for the Acylation of 3-Alkylamino-2-chloro-1,4-naphthoquinones with Acid Anhydrides to Give Intermediates (88b–94b, 95, 96, 98).

The corresponding 3-alkylamino-2-chloro-1,4-naphthoquinone was treated with the corresponding acid anhydride (10 equiv) and conc. H2SO4 (2 drops), and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h. Upon completion, distilled water was added to quench excess anhydride and the mixture was extracted with 3 × 15 mL of DCM. The combined organic layer was sequentially washed with water and brine (20 mL), dried over Na2SO4, concentrated under reduced pressure, and purified by column chromatography (16:1 to 4:1 hexane/EtOAc or DCM/EtOAc) to give the desired products as yellow liquids. This procedure is referred to as Procedure B in the SI.

General Procedure for the Reaction of Acylated 3-Alkylamino-2-chloro-1,4-naphthoquinones with Alkylamines to Give Intermediates (38a–65a, 71a–74a).

The acylated 3-alkylamino-2-chloro-1,4-naphthoquinone was dissolved in 5 mL of acetonitrile and heated to 45 °C. The corresponding alkylamine (3 equiv) was added to the stirred solution, and the resulting mixture was stirred at 45 °C for 1 h. Upon completion, the reaction mixture was adsorbed onto silica gel and purified by column chromatography (8:1 to 1:1 hexane/EtOAc or DCM/EtOAc) to give the product, usually as a reddish liquid. This procedure is referred to as Procedure C in the SI.

General Procedure for the Synthesis of Series 1–4.

HBr solution (48%) in water (15 equiv) was added dropwise to a stirred solution (45 °C) of the N,N-disubstituted or N-substituted dioxonaphthalenylacetamide intermediate dissolved in 1:1 ethanol/EtOAc. Stirring was continued overnight at 45 °C, after which the reaction mixture was purified by silica column chromatography (2–10% MeOH/DCM) to give the desired product as a yellow solid. This procedure is referred to as Procedure D in the SI.

Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv (ATCC 27294) and Mycobacterium bovis BCG (ATCC 35734) were grown at 37 °C in complete Middlebrook 7H9 broth supplemented with 0.05% Tween-80, 0.5% glycerol, and 10% Middlebrook albumin-dextrose-catalase or complete Middlebrook 7H10 agar supplemented with 0.5% glycerol and 10% oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase. Catalase-free complete Middlebrook 7H9 broth was supplemented with 0.05% Tween-80, 0.5% glycerol, 0.5% bovine albumin, 0.2% glucose, and 0.085% NaCl. Complete Middlebrook 7H9 medium without 0.5% glycerol was prepared and used in experiments to detect glycerol dependency.

Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (MICs).

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of test compounds were determined on M. bovis BCG and M. tuberculosis H37Rv following a previously described broth dilution method.24 Briefly, mid-log phase M. bovis BCG and M. tuberculosis H37Rv cultures (OD600 = 0.4–0.6) were adjusted to OD600 = 0.1 in complete 7H9 broth. Aliquots (100 μL) of bacterial suspension were dispensed into flat-bottom transparent 96-well plates (Costar Corning) containing 100 μL of 2-fold serially diluted test compounds per well. Plates were then sealed with Breathe-Easy sealing membrane (Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated for 5 days at 37 °C at 110 rpm (M. bovis BCG) or for 7 days at 37 °C at 80 rpm (M. tuberculosis H37Rv). After incubation, cultures were manually resuspended and absorbance at 600 nm was read on a Tecan Infinite M200 PRO plate reader. MIC50 and MIC90 are the concentrations needed to inhibit 50 and 90% of bacterial growth, respectively, compared to untreated drug-free controls.

Determination of Minimum Bactericidal Concentrations (MBCs).

Minimum bactericidal concentrations (MBCs) of test compounds were determined by colony-forming unit (CFU) enumeration on complete Middlebrook 7H10 agar as described previously.23 Briefly, mid-log phase M. bovis BCG (or M. tuberculosis H37Rv) cultures at OD600 = 0.4–0.6 were adjusted to OD600 = 0.05 (approximately 5 × 106 CFU/mL) in complete 7H9 broth. The diluted cultures were then exposed to 0.5-, 1-, 2-, and 4-fold MIC90 concentrations of respective compound at 37 °C, 110 rpm for 5 days (or at 37 °C, 80 rpm for 7 days for M. tuberculosis H37Rv). Drug-free (DF) cultures were plated out at the start of the experiment to determine the initial bacterial inoculum. After drug treatment, appropriate dilutions of compound-treated cultures were plated out on complete 7H10 agar to determine CFUs. MBC90, MBC99, and MBC99.9 are the concentrations required to reduce CFUs by 10-, 100-, and 1000-fold, respectively, compared to the untreated inoculum at time point zero.

Determination of Time-Kill Kinetics.

The 28-day time-kill kinetic profiles of test compounds were determined as follows. Briefly, pellets of mid-log-phase M. bovis BCG (OD600 0.4–0.8) were spun down (3200g, 10 min) and resuspended in fresh complete Middlebrook 7H9 broth at OD600 0.1. Diluted cultures were treated with test compounds at different concentrations and incubated at 37 °C for 28 days with shaking. At selected time points, the samples were removed for CFU determination on complete Middlebrook 7H10 agar. Isoniazid (INH) at 4× MIC90 (12.8 μM) was employed as control.

Determination of Wayne-Cidal Concentrations (WCCs).

The Wayne-cidal concentrations (WCCs) of test compounds against hypoxic, nongrowing, phenotypically drug-tolerant M. bovis BCG were determined following a method described previously.58,59 Briefly, mid-log phase M. bovis BCG culture (OD600 = 0.4–0.6) was adjusted to OD600 = 0.005 in complete Dubos broth (BD Difco) containing 0.05% Tween-80 and 10% Dubos medium albumin. Diluted cultures (17 mL) were aliquoted and incubated in sealed glass tubes at 37 °C with stirring at 170 rpm for 20 days to deplete oxygen. The generation of a hypoxic culture was visualized by decolorization of methylene blue (1.5 μg/mL) in one control tube. By day 20, compounds at indicated concentrations were injected into tubes via septa in the caps, and tubes were immediately sealed again to minimize the influx of oxygen. CFUs of day 20 culture were plated out on complete 7H10 agar to determine the bacterial inoculum at the start of drug treatment (time point zero of drug treatment). Tubes added with drugs were incubated for another 5 days under similar conditions. After the 5-day incubation period, appropriate dilutions of cultures were plated out to determine CFUs. WCC90, WCC99, and WCC99.9 are defined as the minimum concentrations needed to cause 10-, 100-, and 1000-fold reductions in CFUs, respectively, compared to the untreated inoculum at time point zero of drug treatment (day 20). INH (15 μM) and rifampicin (RIF, 15 μM) were employed as negative and positive controls, respectively.

Determination of Loebicidal Concentrations (LCCs).

A previously reported method was followed to determine the Loebicidal concentrations of test compounds against nutrient-starved, non-replicating, phenotypically drug-tolerant M. tuberculosis H37Rv cells.23,60 Briefly, mid-log-phase M. tuberculosis H37Rv cultures (OD600 = 0.4–0.6) in complete 7H9 broth were spun down and washed three times in 1× PBS supplemented with 0.025% Tween-80. Pellets were then resuspended in 1× PBS-Tween-80 (0.025%) at OD600 = 0.1 and incubated for 14 days at 37 °C under nutrient-starved conditions. Thereafter, cultures were adjusted to OD600 = 0.05 in 1× PBS-Tween-80 (0.025%) and treated with indicated concentrations of test compounds for 7 days at 37 °C, 80 rpm. Appropriate dilutions of cultures were plated out at the start and at the end of drug treatment to determine CFUs. LCC90, LCC99, and LCC99.9 are the minimum concentrations required to bring about 10-, 100-, and 1000-fold reductions in CFUs, respectively, compared to the drug-free inoculum at time point zero. INH and RIF both at 15 μM were employed as negative and positive controls, respectively.

Membrane Potential and Permeability Determinations.

Reported methods were followed to determine the membrane depolarizing and permeabilizing activities of test compounds on M. bovis BCG cultures.23,24 Briefly, M. bovis BCG cultures at mid-log phase were diluted at OD600 0.1 in complete 7H9 broth. Diluted cultures were treated with test compounds at 4× MIC90 for 48 h. At selected time points, aliquots were removed from culture media and tested for changes in membrane potential using BacLight Bacterial Membrane Potential kit (Life Technologies, CA) and membrane permeability using fluorescent probes SYTO-9 and propidium iodide (PI) (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen, MA). RIF at 4× MIC90 (0.08 μM) was used as the negative control for both assays. Carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP) at 100 μM and a detergent SDS (sodium dodecyl sulfate) at 5% (v/v) were used as the positive controls in membrane potential and permeability tests, respectively. In the membrane permeability assay, drug-treated samples were normalized against drug-free cultures (0% permeabilization) and SDS-treated cultures (100% permeabilization) to give % permeabilization.23

piniBAC Cell Membrane Stress Reporter System.

A previously reported method was followed.24 Briefly, test compounds and the positive control INH (0.4–25 μM) were incubated with the recombinant M. bovis BCG-piniBAC-RFP strain at OD600 0.2 for 24 h. Thereafter, red fluorescence (RFU, λEx 587 nm/λEm 630 nm) and OD600 readings of cultures were recorded on a Tecan Infinite M200 PRO plate reader to assess induction of promoter activity. INH was employed as positive control. Normalized fluorescence readings (RFU/OD600) were recorded to account for changes in cell number during the incubation period.

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Detection by CellROX Green Reagent.

The generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in test compound-treated M. bovis BCG cultures was monitored using CellROX Green Reagent (Invitrogen, MA). To monitor the dose-dependent ROS generation, M. bovis BCG pellets at mid-log phase were harvested by centrifugation (3200g, 10 min) and adjusted to OD600 0.3 in complete 7H9 broth. Diluted cultures were treated with test compounds at 0.25×, 0.5×, 1×, and 2× MIC90 at 37 °C for 1 h. Aliquots of CellROX Green Reagent were added to test cultures to give a final concentration of 10 μM. Cultures were then incubated at 37 °C for another 30 min in the dark. OD600 and green fluorescence (GFU, λEx 485 nm/λEm 520 nm) readings were then recorded on a Tecan Infinite M200 PRO plate reader to give normalized fluorescence readings (GFU/OD600). In this assay, INH and naphthoquinone were employed as negative and positive controls, respectively. To monitor the time-dependent ROS generation, a similar procedure was followed, but with some modifications. Briefly, OD600 0.3 M. bovis BCG cultures were treated with test compounds at 2× MIC90 for 24 h. During this time, aliquots (500 μL) of the cultures were withdrawn at the start (0 min) and thereafter at 30, 90, 270 min, and 24 h. Upon withdrawal, the aliquots were treated with 10 μM CellROX Green Reagent dye for 30 min, after which GFU and OD600 readings were recorded. At the same time, additional aliquots of culture media were withdrawn, serially diluted, and plated on complete 7H10 agar for CFU counting.

pfurA Oxidative Stress Reporter System.

A recombinant strain M. bovis BCG-pfurA-RFP was used as a reporter system to detect the oxidative stress caused by test compounds. To generate this recombinant strain, M. bovis BCG was transformed via electroporation with an integrative plasmid carrying a kanamycin resistance gene and the mCherry red fluorescent protein (mRFP) gene under the control of the promoter pfurA. Details of the plasmid constructs are provided in the Supporting Information (Section S17). Recombinant strains were selected using kanamycin (25 μg/mL)-containing 7H10 agar plates. The evaluation of compound-induced oxidative stress was carried out as follows. Briefly, M. bovis BCG-pfurA-RFP at mid-log phase were spun down (3200g, 10 min) and resuspended in fresh complete 7H9 broth at OD600 0.2. Diluted cultures were treated with test compounds at 0.25×, 0.5×, 1×, and 2× MIC90 at 37 °C, 110 rpm for 24 h. Thereafter, OD600 and red fluorescence (RFU, λEx 587 nm/λEm 630 nm) readings were taken on a Tecan Infinite M200 PRO plate reader and expressed as normalized fluorescence readings (RFU/OD600) to account for changes in cell number during the incubation period. INH was employed as the negative control.

Antimycobacterial Activity of Test Compounds on the M. bovis BCG katG Mutant Strain.

M. bovis BCG katG mutant strain harboring a CG deletion mutation at 633–634 bp showing a significantly truncated aberrant protein product of only 211 amino acids was spontaneously isolated in vitro against INH at an approximate mutation frequency of 10−6/CFU. Whole genome sequencing (Novogene AIT, Singapore) and targeted sequencing (Bio Basic, Singapore) were performed to identify and confirm the katG mutation. Reported primers used in the targeted sequencing were: 5′-TCCTGTTGGACGAGGCGGAG-3′ and 5′-CCGTCTCGTCATCCCCGTCT-3′ to amplify the katG gene; 5′-TGGGAGCCCGATGAGGTCTA-3′, 5′-AGATCCTGTACGGCTACGAG-3′, 5′-GGCGAAGCCGAGATTGCCAG-3′, 5′-ACAGCCACCGAGCACGAC-3′, 5′-GTCCCGTCATCTGCTGGCGA-3′, and 5′-CCATGGGTCTTACCGAAAGT-3′ to confirm the observed katG mutation (Bio Basic, Singapore).50

To determine the antimycobacterial activity of test compounds on the M. bovis BCG katG mutant strain, 5-day MIC determinations were carried out as described earlier using catalase-free complete 7H9 broth as culture media. Concurrent determinations were carried out on the wild-type strain. Dose response curves were plotted to detect MIC shifts. INH was employed as the control drug. For test compounds 32 and 61, antimycobacterial activity was also determined by CFU enumeration on complete 7H10 agar. Briefly, test compound (1×, 2× MIC90) was separately incubated with the katG mutant and wild-type M. bovis BCG in catalase-free complete 7H9 media for 5 days at 37 °C, 110 rpm. Thereafter, aliquots of the cultures were serially diluted and plated on complete 7H10 agar for CFU counting. INH at 4× MIC90 (12.8 μM) was employed as the control.

Supplementation with Vitamin C.

To determine the potentiating effects of vitamin C (L-ascorbic acid, Merck) on antimycobacterial activity, mid-log-phase M. bovis BCG cultures diluted to OD600 0.05 in catalase-free complete 7H9 broth was treated with test compound 32 (0.5×, 1× MIC90) at 37 °C, 110 rpm for 5 days with and without the presence of 2.5 mM vitamin C. After 5 days of drug treatment, aliquots of the cultures were serially diluted and plated on complete 7H10 agar for CFU counting.

Supplementation with Antioxidants.

To evaluate the rescue effects of antioxidants (N-acetylcysteine, TEMPO, thiourea), 5-day MIC determinations of test compounds with or without supplementation of antioxidant were carried out on M. bovis BCG cultures grown in catalase-free complete 7H9 broth. Dose response curves were plotted to detect MIC shifts. The antioxidant was tested at two concentrations that had no growth inhibitory effects on M. bovis BCG.

Isolation of Resistant Mutants.

Attempts to raise spontaneous drug-resistant mutant strains from the parental strain M. tuberculosis H37Rv was carried out as previously described.23 Two independent attempts at mutant selection were made. Briefly, 3 × 108 M. tuberculosis H37Rv cells at mid-log phase were plated on complete 7H10 agar plates containing 32 or 48 at 1×, 2×, 4×, and 8× MIC90. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 8 weeks. Colonies that appeared on selection plates would be isolated and restreaked on agar containing the same concentration of 32 or 48 for colony purification and verification of drug resistance.

Checkerboard Titration Assay.

A previously reported method was followed to test the synergistic interactions of 32 with anti-TB drugs.53,54,61 Twofold serial dilutions of 32 and one interested anti-TB drug were made in complete 7H9 broth in a flat-bottom transparent 96-well plate (Costar Corning). Eight concentrations of 32 were tested for synergy against 11 concentrations of the interested anti-TB drug, resulting in 88 different combinations tested in one 96-well plate. To each well which contains 100 μL of drug combination mixture was added an aliquot (100 μL) of mid-log-phase M. tuberculosis H37Rv suspension adjusted to OD600 0.1. Plates were then sealed with a Breathe-Easy sealing membrane (Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated for 7 days at 37 °C with agitation at 80 rpm. Each plate had media-only and drug-free controls. After 7-day incubation, cultures were manually resuspended and OD600 was recorded on a Tecan Infinite M200 PRO and used to calculate the bacterial growth inhibition percentage of each well. The fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI) was calculated using the concentrations of the drugs at which at least 90% of bacterial growth was inhibited in the well compared to the drug-free culture, using the formula shown below53

Synergy is defined as FICI ≤ 0.5, indifference as 0.5 < FICI ≤ 4, and antagonism as FICI > 4. Experiments were performed at least twice independently with technical replicates.

Interference Compounds.

A quinone is embedded within the naphthoimidazolium and other scaffolds in the compound library (series 1–4, 6). We have shown that redox cycling by the quinone contributes to the bactericidal activity of these compounds. On the other hand, redox cycling is flagged out as subversive reactivity, commonly associated with Pan Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS). Thus, we asked if the activities of our best candidates are in fact artifacts arising from promiscuous redox cycling by the quinone. This possibility was discounted for two reasons. First, all 80 compounds in series 1 have the same quinone-bearing scaffold, but their MIC90 BCG values ranged from 40 to 0.22 μM (Table 1). This is evidence of a dynamic structure–activity relationship, which would not be observed if these compounds are nonspecific redox cyclers. Second, active candidates (32, 48, 61) and less active candidates (72, 73) were clearly differentiated in their ability to generate intracellular ROS in M. bovis BCG cultures at growth inhibitory MIC90 concentrations (Figure 6). Yet both classes of compounds have a common quinone-bearing scaffold that differ only in the presence of a positively charged center. Hence, we conclude that notwithstanding the presence of the quinone moiety, the compounds investigated in this report are not PAINS.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by the Ministry of Education (MoE) Academic Research Fund R148000286114 to M.L.G., and Ministry of Health National Medical Research Council NMRC/TCR/011-NUHS/2014 (Singapore) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (USA) R01AI132374 to T.D. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The authors gratefully acknowledge MoE Singapore for scholarships to K.T.F. and D.A.N., Dr. David Alland, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, for providing the piniBAC reporter plasmid, Dr. Yoshiyuki Yamada, National University of Singapore, for constructing the reporter strains of M. bovis BCG-piniBAC-RFP and M. bovis BCG-pfurA-RFP, Dr. Annanya Shetty for the isolation and whole genome sequencing of the spontaneous isoniazid-resistant katG mutant in M. bovis BCG, and Prof. Nicholas Paton for BSL3 core facility of NUHS.

ABBREVIATIONS

- BCG

Bacillus Calmette-Guerin

- CFU

colony-forming unit

- CFZ

clofazimine

- CCCP

carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazine

- cLogP

calculated logarithm to base 10 of partition coefficient P

- DiOC2

3,3-diethyloxacarbocyanine iodide

- MIC

minimum inhibitory concentration

- MBC

minimum bactericidal concentration

- NDH2

type II NADH dehydrogenase

- PI

propidium iodide

- R(G)FP

red (green) fluorescent protein

- PAMPA

parallel artificial membrane permeability assay

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- PK

pharmacokinetics

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c01383.

Syntheses of series 5 and 6; characterization of intermediates and final compounds; purity data of final compounds; NMR, MS, and HPLC data of compounds 32, 48, and 61; Vero cells IC50; solubility; PAMPA Pe; in vitro rat microsomal stabilities; mini-Ames test of selected actives; in vivo mouse PK of 32 and 61; dose response curves of M. bovis BCG in the presence of test compounds and glycerol, antioxidants, and vitamin C; dose response curves of wild-type and katG loss-of-function mutant M. bovis BCG in the presence of selected test compounds; plasmid and primers used in the construction of pfurA-RFP reporter system; NADH oxidation; and O2 consumption by inverted membrane vesicles (PDF)

Molecular formula strings (CSV)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c01383

Contributor Information

Kevin T. Fridianto, Department of Chemistry, National University of Singapore, 117543, Singapore.

Ming Li, Department of Pharmacy, National University of Singapore, 117543, Singapore.

Kiel Hards, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Otago, Dunedin 9054, New Zealand;.

Dereje A. Negatu, Center for Discovery and Innovation, Hackensack Meridian Health & Department of Medical Sciences, Hackensack Meridian School of Medicine, Nutley, New Jersey 07110, United States

Gregory M. Cook, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Otago, Dunedin 9054, New Zealand

Thomas Dick, Center for Discovery and Innovation, Hackensack Meridian Health & Department of Medical Sciences, Hackensack Meridian School of Medicine, Nutley, New Jersey 07110, United States; Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Georgetown University, Washington, District of Columbia 20057, United States;.

Yulin Lam, Department of Chemistry, National University of Singapore, 117543, Singapore;.

Mei-Lin Go, Department of Pharmacy, National University of Singapore, 117543, Singapore;.

REFERENCES

- (1).World Health Organisation. Fact Sheet, Tuberculosis, 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis (accessed Oct 14, 2020).

- (2).Cumming BM; Lamprecht D; Well RM; Saini V; Mazorodze JJ; Steyn AJC The physiology and genetics of oxidative stress in mycobacteria. Microbiol. Spectrum 2014, 2, No. MGM2-0019-2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Kumar A; Farhana A; Guidry L; Saini V; Hondalus M; Steyn AJC Redox homeostasis in mycobacterial: the key to tuberculosis control? Expert Rev. Mol. Med 2011, 13, No. e39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Voskuil MI; Bartek IL; Visconti K; Schoolnik GK The response of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Front. Microbiol 2011, 2, No. 105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Kohanski MA; Dwyer DJ; Hayete B; Lawrence CA; Collins JJ A common mechanism of cellular death induced by bactericidal antibiotics. Cell 2007, 130, 797–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Dwyer DJ; Belenky PA; Yang JH; MacDonald IC; Martell JD; Takahashi N; Chan CTY; Lobritz MA; Braff D; Schwarz EG; Ye JD; Pati M; Vercruysse M; Ralifo PS; Allison KR; Khalil AS; Ting AY; Walker GC; Collins JJ Antibiotics induce redox-related physiological alterations as part of their lethality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2014, 111, E2100–E2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Lobritz MA; Belenky PA; Porter CBM; Gutierrez A; Yang JH; Schwarz EG; Dwyer DJ; Khalil AS; Collins JJ Antibiotic efficacy is linked to bacterial cellular respiration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2015, 112, 8173–8180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Liu Y; Imlay JA Cell death from antibiotics without the involvement of reactive oxygen species. Science 2013, 339, 1210–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Keren I; Wu Y; Inocencio J; Mulcahy LR; Lewis K Killing by bactericidal antibiotics does not depend on reactive oxygen species. Science 2013, 339, 1213–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).WHO. WHO Consolidated Guidelines on Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis Treatment; World Health Organization, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Yano T; Kassovska-Bratinova S; Teh JS; Winkler J; Sullivan K; Isaacs A; Shechter NM; Rubin H Reduction of clofazimine by mycobacterial type 2 NADH: quinone oxidoreductase. J. Biol. Chem 2011, 286, 10276–10278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Beites T; O’Brien K; Tiwari D; Engelhart CA; Walters S; Andrews J; Yang HJ; Sutphen ML; Weiner DM; Dayao EK; Zimmerman M; Prideaux B; Desai PV; Masquelin T; Via LE; Dartois V; Boshoff HI; Barry CE III; Ehrt S; Schnappinger D Plasticity of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis respiratory chain and its impact on tuberculosis drug development. Nat. Commun 2019, 10, No. 4970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Tyagi P; Dharmaraja AT; Bhaskar A; Chakrapani H; Singh A Mycobacterium tuberculosis has diminished capacity to counteract redox stress induced by elevated levels of endogenous superoxide. Free Radical Biol. Med 2015, 84, 344–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Heikal A; Hards K; Cheung CY; Menorca A; Timmer MSM; Stocker BL; Cook GM Activation of type II NADH dehydrogenase by quinolinequinones mediates antitubercular cell death. J. Antimicrob. Chemother 2016, 71, 2840–2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]