Abstract

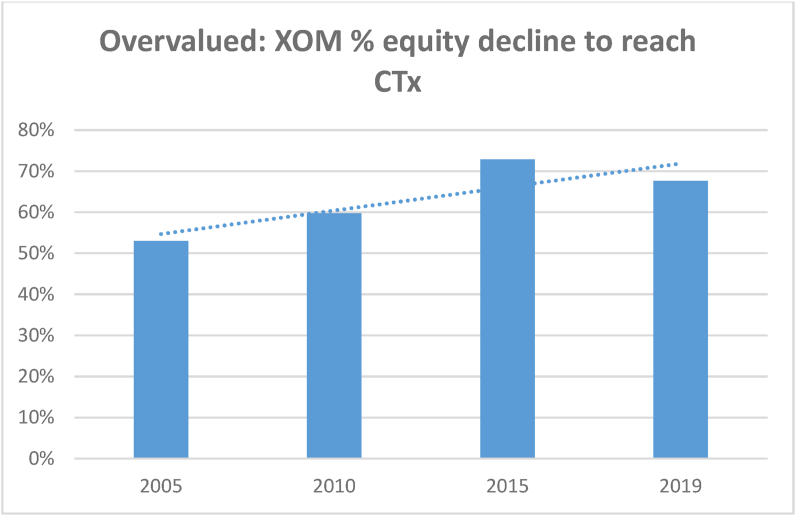

This paper examines ExxonMobil, a widely-followed, mature, large oil and gas producer using discounted cash flow valuation modeling under two scenarios: “Business as usual”; and an adequate climate policy response that would limit warming to 1.5C. The analysis across the last two decades shows the market continues to price in a “business as usual” future. ExxonMobil's overvaluation, relative to an adequate policy response scenario, has increased (pre-pandemic) from 50% to 70% of equity value at risk. Investors are taking significant energy transition risk without meaningful compensation. To avoid continued capital misallocation, negative externalities should be incorporated into underwriting.

Keywords: Energy transition, Asset pricing, Valuation, Carbon risk, Climate change

Energy transition, Asset pricing, Valuation, Carbon risk, Climate change.

1. Introduction1

By December 2019 (just prior to the pandemic), oil and gas producers underperformed the broader market for multiple years.2 Did underperformance reflect: a deep value bargain with outsized return prospects; or the classic “falling knife”- a beaten-up stock still too expensive given declining future prospects and high business risk? This article assesses the pricing of the energy transition, in magnitude and over time, by employing two discounted cash flow (DCF) valuation models with polar opposite assumptions. This framework examines ExxonMobil (Ticker: XOM), as a case study, and proxy for fossil fuel valuations. The analysis demonstrates that fossil fuel producers are significantly overvalued (equity value at risk of up to 70%) as energy transition risks have not been meaningfully priced in. From 2005 to 2019, market prices tracked “business as usual” valuations -seemingly ignoring the risk to fossil fuel producers' business models. Moreover, the discrepancy has grown between market prices and a valuation based on a 1.5C carbon policy.

To mitigate climate change, oil and gas producers need to shrink dramatically over the next 10–30 years, resulting in rapidly declining cash flows and terminal values descending toward zero at the equity level. Additionally, negative growth raises concerns about distress and business risk (Damodaran, 2009a; Altman, 1993). S&P Global Ratings warned that these companies, “face significant challenges and uncertainties engendered by the energy transition, including market declines due to the growth of renewables” (Robertson, 2021).

Despite the investment risks, investors and analysts are often slow to price significant secular transitions for reasons including: reliance on backward-looking data/models; difficultly/costs in arbitraging overvalued stocks over longer time periods; assumed career risk for short-term underperformance; seemingly gradual and uncertain timeframes; “herding” and “groupthink” biases, etc. (Riedl, 2020).

Of the two DCF valuations models, “business as usual” (BAU), relies on historic mean-reverting revenue growth, operating margins, and oil prices. BAU is a straightforward valuation of a commodity producer if climate change and improving renewable technologies didn't exist. At the other extreme, “Carbon Tax” (CTx) is a DCF valuation estimate based on immediate, adequate policy responses to meet 1.5C. CTx relies the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)'s estimates of the carbon budget and industry supply cost curves to determine price and quantity decline.

The investment implication is that BAU pricing provides adequate return for transition risk if there is no transition. BAU assumes a higher growth future than even OPEC expects. Any decelerating fossil fuel growth would deliver poor returns for current investors. A CTx valuation fully prices in transition risk and reduces the need to profit from negative externalities.3 Given the expected imprecision around any DCF valuation, modest differences between stock price and a carbon tax scenario would be inconclusive, suggesting energy transition risk may be accounted for. Yet, at least prior to the pandemic, valuation differences were 50% and generally continued to increase toward 70%.

While the secular dynamics are industry-wide, ExxonMobil provides an instructive and generalizable case study. If the energy transition has been priced into equity markets it should be readily apparent in ExxonMobil's stock price due to its size, maturity, relationship with oil prices, and extensive analyst coverage. Firm management has been highly resistant to transitioning away from fossil fuels,4 and its investments in high cost projects only heightens its operating leverage, further increasing transition risk sensitivity.

Fair value analysis should guide investment decisions so investors are paid for risks taken. Thoughtful investment underwriting should be forward looking, and incorporate near-term catalysts and impactful, measurable risks. At current valuations earning a market return is at risk since it is highly dependent on the continuation of large negative externalities and other subsidies (totaling approximately 6% of global GDP, Coady et al., 2019).

Identification of mispriced assets can generate strong risk-adjusted returns, particularly when catalysts can cause convergence toward “fair value”. However, profiting from overpriced assets is difficult since shorting has higher costs/risks, particularly over a multi-year timeframe. Still, if markets are underreacting to the energy transition, positive excess returns are available for those who avoid overvalued oil and gas producers (Cornell and Damodaran, 2020, p. 14).

This paper seeks to address questions that the literature is largely silent on: how close fossil fuel stocks are to “business-as-usual” assumptions? and how far these stocks would fall if an adequate policy response were put in place? The greater the mispricing, the greater the potential damage to investors, the economy and the environment. Misallocated capital will eventually require investors to write off assets. Financial leverage perpetuates and magnifies the cycle, as debt covenant violations and default rates increase, further exacerbating downward price pressure on fossil fuel assets and across the economy (Comerford and Spiganti, 2016). This article's analysis seeks to measure the magnitude of mispricing not only for investors but also for regulators and policy makers.

The approach here is not to formulaically assume that companies that “do good” are consistently more profitable and therefore superior investments. It is an assessment of the risk and return potential of a representative firm in an industry facing extreme transition. The approach also does not assume an increased cost of capital due to investor's morale distaste for climate pollution. A higher capital cost initially depresses value but thereafter increases future returns. In fact, after the transition risks are priced in, these stocks would provide an adequate investment return. In contrast, an ESG-based argument would continue to proscribe these stocks, regardless of share price.

The pre-pandemic era (pre-2020) is primarily examined to avoid excessive “noise”. Yet the drastic decline of 2020 and rapid recovery of early 2021 seems more consistent with a short-term market focus than either a long-view bull or bear thesis.

Following the Introduction: Section 2 reviews recent literature on the energy transition; Section 3 the carbon budget and reasons for mispricing; Section 4 details near term catalysts; Sections 5 discusses ExxonMobil's characteristics of decline; Section 6 delves into the BAU and CTx valuation framework, assumptions, and valuations; Section 7 discusses valuation differences by magnitude, across time, and in comparison to other estimates; Section 8 reviews alternative arguments; Section 9 explores the pandemic impact; followed by the Conclusion and the path ahead.

2. Literature review

Academic and practitioner research has indicated underpricing of energy transition risk and the downside potential of carbon-intensive business models. Griffin et al. (2015) find limited negative stock market reactions to concerns about a carbon bubble and stranded assets for the largest oil and gas firms, indicating risk pricing may be inadequate. More recently, Kumar et al.'s (2019) findings are consistent with market mispricing, as a firm's climate risk exposure aid in predicting returns. In et al. (2017) find evidence that a portfolio long low carbon stocks and short high carbon stocks will generate positive abnormal returns. This investment approach has been undertaken by Litterman (2011; 2013). However, to profit from shorter-term approaches, like swaps, the implication is that the valuation gap must be closing to some degree. Ilhan et al. (2019) found that the cost of option protection against downside tail risks increases for firms with greater carbon risk.

Yet transition risk may be not fully integrated by most investors, who look at future cash flow projections through judgment bias, heuristics, and intuitive inference derived from past observations and experiences (Gennaiolli and Shleifer, 2010). Generally, cash flow scenarios used by financial analysts exclude carbon emission references and possible future repricing of assets (Naqvi et al., 2017). The CFA Institute surveyed its community of financial analysts and only about 40% of all survey respondents incorporate climate change information into the investment process (Orsagh, 2020). Krueger et al. (2020) survey institutional investors and find that the “two most common approaches (analyses of carbon footprints and stranded asset risks) have been used by less than half of them.” Additionally, the average survey respondent “believes that equity valuations do not fully reflect the risks from climate change. Overvaluations are considered to be largest among oil firms,” although the magnitudes of the overvaluations are believed to be modest. The timeframe of many material physical climate risks may seem slow-moving, highly uncertain, and distant (Barnett et al., 2020). Unlike physical risks however, regulatory risks can occur abruptly and unpredictably (e.g., after an election).

Collectively these studies demonstrate the presence of energy transition risk in current market prices. The analysis below further demonstrates how little of this risk has actually been incorporated into fossil fuel company valuations, and the potential magnitude of investor equity at risk.

3. Fossil fuel “Bubble”?

“Carbon Bubble” primarily refers to the excess amount of fossil fuel reserves relative to what can be burned with current technology before reaching a critical warming threshold. In this case, overvaluation, or “bubble”, is not of the “irrational exuberance” dynamic, but illustrative of poor incentives and humanity's slow mental adaptation to rapid changes.5

Even with suboptimal risk/return prospects, investors may continue to invest in the fossil fuel industry. Many institutional investors place energy within its own category, or sub-category within natural resources, making movement away from such investments “stickier” (Silver, 2017). Investors are likely to view the exclusion of an entire industry, as increasing career risk (potentially increasing redemptions due to unique short-term underperformance). Abreu and Brunnermeier (2003) show significant mispricings persist, even when recognized, if investors have differing opinions regarding the time to reach fair value.

Damodaran (2009a) notes the challenge in valuing companies near the end of their life-cycle due to “psychological” reasons, as we are “hard wired for optimism”. Analysts often find that the “tools and approaches that served them adequately with healthy companies” fail them with declining firms. “This problem is worse when a sector with a history of financial health becomes troubled, since analysts are slow to let go of “old rules of thumb and metrics” (Damodaran, 2009a). These include continued use of positive growth rates in perpetuity, and modelling mean-reversion of prices and margins to historic averages, thereby underpricing secular transitions. For example, in 2019, the IEA forecasted roughly 0.5% annual oil demand growth through its peak around 2040 (Birol, 2019). Yet analysts' reports anticipated ExxonMobil's long-term growth to be between 4.7% to 15%, outpacing long-term economic growth expectations.6

Investment professionals may suffer from “groupthink” bias. Surveys indicate fossil fuel investment professionals: are more apathetic than the general population to climate change; tend to underestimate impacts from climate policies and technology; possess poor knowledge of market relevant climate change information; and maintain a disbelief in government's ability to meet climate targets (Critchlow, 2015; Naqvi et al., 2017). This is further compounded by the perceived slow pace of change (Critchlow, 2015; Weber, 2010; Reber et al., 1998).

The lack of corporate transparency makes these risks harder to price. For example, a KPMG (2008) study found that 68% of companies surveyed (nearly 1,500 companies) did not address climate change as a business risk. Additionally, 41% of the 250 largest global companies, reported “no information on their carbon footprint” (Solomon et al., 2011). Resultingly, investors are generally unaware of the carbon footprint within their portfolios, or a firm's “stranded asset” risk (Andersson et al., 2016).

4. Catalysts

Without catalysts, potential investment gains may prove elusive, as the subsequent move to “fair value” becomes highly uncertain over a reasonable period.7

There are at least three fast approaching catalysts:

4.1. Science is clear

A rapid scale transformation is required by 2030, with reduction of cumulative CO2 emissions to net zero by mid-century (Rogelj et al., 2018). The median 1.5C scenario with limited overshooting or reliance on CCS (Carbon Capture and Sequestration) shows roughly 90% declines in oil and gas by mid-century (Rogelj et al., 2018).

4.2. Additive policy impacts and increasing policy pressures

Meaningful polices have already been initiated (e.g., 20% of world's emissions covered by a carbon market/price, Orsagh, 2020). With the reentry of the USA, the Paris Agreement applies essentially to the entire globe. Carbon Tracker calculated that to be “Paris-aligned”, “the seven energy majors' average oil and gas production volumes would need to fall 35% by 2040” (Carbon Tracker, 2019a).

There is growing agreement among voters on climate action (Marlon et al., 2020), particularly those under 40, including Republicans (Luntz, 2019). This may be in part due to increasingly dramatic and observable climate impacts affecting non-fossil fuel businesses and individuals (e.g., increasing $1 Billion disasters, NOAA, 2021, and production and supply chain interruptions, Savitz, 2011). Furthermore, as fossil fuel profits decline and debt burdens grow, there will be less money for political contributions.

4.3. Increasingly cost competitive renewables

Rapidly increasing technology improvements and production cost efficiencies have dramatically decreased renewable energy costs. Bloomberg NEF analysis revealed renewables as the cheapest source of electricity production for 85% of the world8 (Carbon Tracker, 2019a). Electric cars are on pace to make up 50% of the global vehicle fleet by 2035 (Bloomberg NEF, 2019). BP's recent BP Energy Outlook (2020) presentation noted that solar costs are expected to fall 60% or more over the next 30 years (Dale, 2020). The falling costs create a virtuous cycle for further investments and cost efficiencies, as renewable investment returns over 10-years, ending in 2019, substantially exceed fossil fuel returns—despite an average nominal oil price over $70 (IEA and the Imperial College, 2020). Renewable price competition serves as a cap on fossil fuel prices, with any future price spikes accelerating demand shifts (Kemp, 2020).

5. ExxonMobil case study analysis

5.1. Why ExxonMobil?

Formed in 1999 by the merger of Exxon and Mobil, ExxonMobil has business lines in exploration and production, refining, marketing and petrochemicals. With extensive analyst coverage as one of the largest publicly-traded integrated oil and gas companies, the firm is a solid proxy for how investors are pricing the energy transition. Pre-pandemic, ExxonMobil appeared unlikely to undergo financial distress within the next decade,9 reducing a significant individual firm risk from the base valuation. As a mature, commodity producer, ExxonMobil's revenue variance is highly linked to macro commodity price determinants. The firm further amplified its transition risk sensitivity by deploying significant capital in high cost projects, with its lowest cost projects expected to require $40-$50 oil prices to breakeven (Carbon Tracker, 2020b).

5.2. Positioned today: characteristics of decline

Using “Valuing distressed and declining companies” (Damodaran, 2009a) as a guide, do fossil fuel producers demonstrate characteristics of decline? For a commodity company these indicators could be cyclical “noise”. Nonetheless, the entire industry is late life cycle, with headwinds that should dampen growth further. BP and Shell's CEOs have suggested that 2019 may represent peak oil demand (Carbon Tracker, 2020c).

-

1.

Stagnant or declining revenues, with an inability to increase revenues over extended periods despite a strong economy, is a marker of decline. Flat revenues and/or growth less than inflation indicates operating weakness. Exxon's nominal revenues have steadily declined since 2011. Over longer periods, pre-pandemic, the trend was discouraging despite overall economic growth. Exxon's nominal revenues in 2019 are below what they were 15 years prior, even though nominal 2004 oil prices were then about 30% lower. In real terms, ExxonMobil had nearly twenty years of negative revenue growth (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Change in ExxonMobil's (XOM) Real Revenues. SOURCES: Real GDP data from FRED (https://fred.stlouisfed.org); CPI-U data from U.S. Dept. of Labor, BLS (https://www.usinflationcalculator.com/inflation/consumer-price-index-and-annual-percent-changes-from-1913-to-2008/); XOM Revenues (S&P Capital IQ); WTI Spot Oil from Mergent Online/FTSE Russell.

More telling is these aforementioned revenue patterns apply not only to ExxonMobil but also to its closest competitor, Chevron,10 and generally to the overall sector. This suggests the primary difficulties are less specific to Exxon management and more about the industry's dynamics (Damodaran, 2009a).

-

2.

ExxonMobil has experienced declining operating margins due to increased cost structures (Figure 2). Over the last 15 years, operating (production) costs per BOE (barrel of oil equivalent) almost quadrupled from $3.9 to $11.5 per BOE. Similarly, capital costs meant to grow the reserve base (including acquisition, exploration, and development expenses) rose from $9 billion in 2004 to $22.2 billion in 2019 yet proven reserves actually fell. The impact of these poor capital outlays resulted in doubling of deprecation expenses, which rose from $6.3 per BOE in 2004 to $13.1 in 2019 (S&P Capital IQ; Carbon Tracker, 2020b). Moody's Analyst Peter Speer estimates that Exxon needs an oil price of $55 BOE or more just to cover its spending needs (Brower, 2020). This positioning is perilous in an energy transition world, as high cost structures and high capital intensity11 quickly erode operating margins when revenue declines (i.e., operating leverage). Additionally, production costs could further escalate (e.g., due to CCS requirements).

Figure 2.

Production and depreciation costs.

Often, a declining firm's management is in “denial about their status and continue to invest in new assets as if they had growth potential” (Damodaran, 2009a). Growth and cash flows rapidly decline when firms earning well below their cost of capital, with little reason for optimism, continue to deploy capital into high cost projects within a declining sector (Krauss, 2020).

Despite almost tripling capital invested since 2004, ExxonMobil's investments failed to increase either production or proven reserves (Figure 3) (S&P Capital IQ and Carbon Tracker, 2020b). Exxon's acquisitions of Canadian oil sands, and gas producer, XTO Energy, are examples of past missteps. Oil sands are at the highest end of the global oil supply curve, beyond any reasonable “carbon budget” threshold. In early 2021, ExxonMobil wrote these assets off (Crowley, 2021). XTO, a short-cycle shale producer, acquired at a high price based on assumed future demand growth, was outside of Exxon's competitive advantage in managing, large, multi-year megaprojects (Jakab and Lee, 2021). In 2016, 70% of ExxonMobil's future potential projects were higher cost, such as LNG and Heavy Oil/Oil Sands, pointing to continued rising development costs and subsequently, depreciation costs if put into production (Source: ExxonMobil Financial Statements and Carbon Tracker, 2020b).

Figure 3.

XOM total oil equivalent production and total proven reserves.

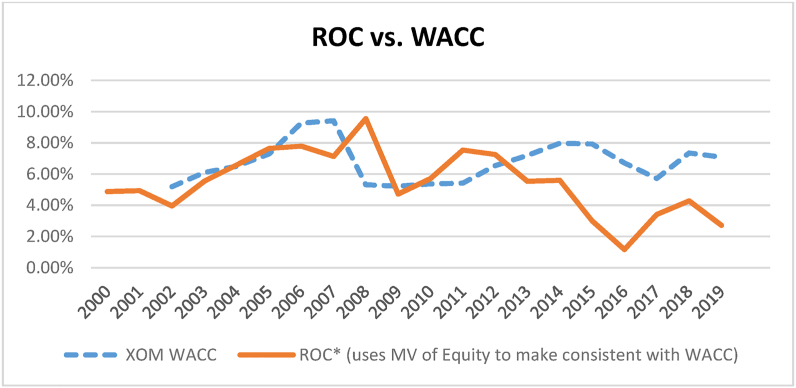

Since 2012, Exxon's return on capital invested has been below the firm's weighted average cost of capital, implying management's capital decisions have eroded shareholder value (Figure 4). Additionally, the cost of capital hurdle could increase as fossil fuel companies are increasingly shunned by large institutional investors (BlackRock, etc.)

-

3.

Declining firms maintain big payouts to shareholders in the form of dividends and stock buybacks, as there are insufficient growth opportunities to generate value. Firms without large in-place debt will “pay out large dividends, sometimes exceeding their earnings but also buy back stock.” ExxonMobil has prided itself on maintaining a generous dividend (Since 2015 the Payout Ratio has never fallen below 66% of Net Income).

-

4.

Asset divestitures are undertaken by declining firms to pay debt obligations, or sustain dividends, “the need to divest will become stronger”. When divestitures occur in an orderly fashion, management either holds assets to receive the present value of cash flows, or sells for a higher amount. The divestiture “follies” begin when declining firms increasingly divest to meet near-term cash flow needs despite poor-timing and weaker bargaining positions. If asset divestitures are viewed as reductions in invested capital, reinvestment rates and growth rates can be negative (Damodaran, 2009a).

Figure 4.

ExxonMobil's return on capital (ROC) and weighted average cost of capital (WACC).

Management tends to adjust slowly to reality and overestimates sales value. For example, ExxonMobil sought to raise cash through the sale of its North Sea assets, yet pricing quickly came in at a 25% to 50% discount to initial aspirations (Bousso and Nasralla, 2020a). During a secular, industry-wide liquidation, things could unravel quickly, resulting in significant “stranded” assets as oil and gas reserves, are difficult to repurpose.

Deteriorating industry dynamics and ExxonMobil's poor investment decisions and high cost structures will intensify divestiture pressure as Cash Flow from Operations (CFO) has generally been inadequate in covering capital expenditures, dividends, and net interest payments (Figure 5). In 2020, Exxon CFO Andrew Swiger said the company could ramp up its upstream asset sales in 2021, continuing “with our previously announced divestment program of $15 billion” and potentially expanding it to assets that were previously within its long-term development plan, such as its North American dry gas assets (Luhavalja, 2020).

-

5.

An Increasing Cost of Capital is likely for declining industries. Financial leverage acquired when firms were in a healthier phase of their life cycle becomes harder to refinance. As of 2019, ExxonMobil's balance sheet (15% debt12) was not highly levered. However, a lengthy phase of low commodity prices could prove challenging (Damodaran, 2009a) and is partially reflected in the firm's repeated, credit downgrades.13 Uncertainty around a firm's revenues and operating income, increase risk as a going concern (which is captured by the cost of capital). The increase of energy market transition risk relative to 10- to 20 years ago, implies discount rates may tend to be more buoyant for the fossil fuel system than long term historic data suggests (Even disregarding ESG-investor shunning of these stocks). At the very least a lower growth rate, reduces terminal values even if the Cost of Capital is constant (as “r-g” increases).

Figure 5.

Cash Flow from Operations less capital expenses and investor payments.

6. Methodology

6.1. Model

A streamlined model of ExxonMobil and oil prices can tease out an approximation of valuation under two “extreme” scenarios. First, without the need to address climate change (“BAU”), long-term assumptions about oil prices, operating margins, and revenue growth could be “normalized” (assuming mean reversion) to smooth out cyclical factors (Damodaran, 2009b). Additionally, valuations for a sizable secular change (i.e., the energy transition) can be obtained in part by altering the net to producer price and growth rates (the CTx model).

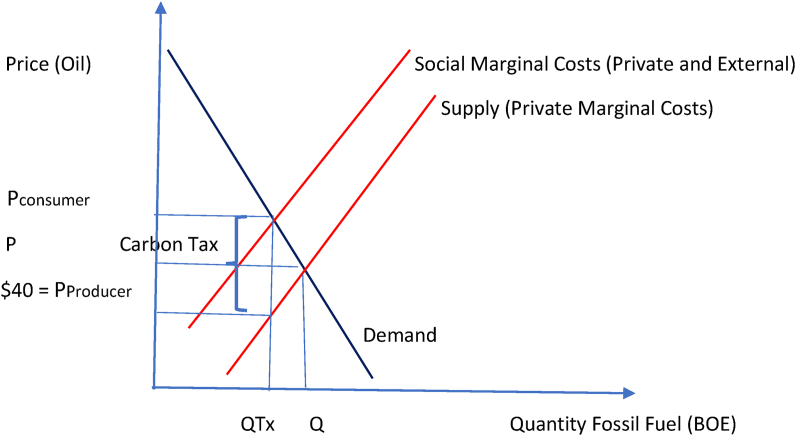

An effective carbon policy (like a Carbon tax) would push down what a producer receives and reduce quantity demanded to meet the carbon budget for 1.5C (Figure 6). As a result, oil prices net to producers would result from the intersection of quantity budgeted (QTx) and an industry aggregated supply curve resulting from marginal costs (including adequate capital returns) and natural decline rates (Carbon Tracker, 2019b).

Figure 6.

Carbon Tax's price and quantity impacts. CTx model: Producers' revenues = QTx ∗ PProducer ($40).

6.1.1. Price impact

Historical oil prices occurred in an environment of rising oil demand. Yet, relatively small market imbalances can lead to sharp price changes, as in 2014–15 when a market disequilibrium of roughly 2 million barrels a day (3% total) contributed to prices falling from over $100 to less than $30 (Landell-Mills, 2018). As a potential precursor, the COVID-19 crisis created a 20% rapid decline in demand overwhelming storage and causing prices to fall over 80% in a few months14 (Toplensky, 2020). Due to operating leverage, net income impacts are even greater. For example, Total's 2017 financial statements, indicate a roughly 50% net income reduction resulting from a 10% oil price decline (Landell-Mills, 2018). ExxonMobil, warned in a regulatory filing, that low energy prices (of around $40/BOE, which incidentally is in line with prices required to meet the carbon budget) could remove as much as one-fifth of its oil and natural gas reserves off its books. If prices persist at these levels, “certain quantities of crude oil, bitumen and natural gas will not qualify as proved reserves” (Crowley and Carroll, 2020).

The BAU model assumes oil prices revert to the inflation-adjusted average since 2000. While CTx assumes long-term oil prices converge around the industry supply curve based on the marginal cost of production, and a quantity demanded approximately consistent with the 1.5 C carbon budget. By examining and aggregating industry-wide production costs (marginal cost curves), an aggregate supply curve can be created by using the “least-cost economic framework to model future supply at the asset level” (Carbon Tracker, 2019b). For 1.6C of warming, Carbon Tracker determined the highest cost field to enter production would need to breakeven at $38 to $40 per BOE for the period 2019–2040 (Carbon Tracker, 2019b, p. 15). Given natural decline rates, Carbon Tracker finds there is little, if any, room for new projects while staying at 1.5C without substantial reliance on CCS technology (currently unproven and uneconomical at any meaningful scale).

Other estimates point to similar pricing.15 In early 2021, energy consultancy, Wood Mackenzie, analyzed the impacts of an accelerated energy transition to limit warming to 2C, and found oil prices falling to approximately $40 by 2030, $30 by 2040 and as low as $10 by 2050 (Hittle et al., 2021). Among oil majors, BP “announced its plan to be break-even for its overall business at $35-$40 BOE by 2021”, and Shell determined that capex must cover its internal rate of return at $40 per BOE (Landell-Mills, 2018).

Prices could crater rapidly even if a carbon tax may not be of consequence for a few years. As the IEA warns, with “a structural reduction in demand, and a clear deadline for full decarbonization”, OPEC members “focus could shift to getting one's own fossil fuels out before others” (Landell-Mills, 2018).

Of the possible regulatory and policy alternatives that would limit emissions for 1.5C world, a carbon tax provides greater transparency and is considered the most efficient economically (Nordhaus, 1993). The Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA) Institute advocates for carbon price expectations to be included in analyst reports.

“A realistic market price on carbon will send a price signal that analysts need in order to properly value the externalities that come with greenhouse gas emissions. CFA Institute recommends that investment professionals account for carbon prices and their expectations thereof in climate risk analysis. The externality of climate change has a cost, and that cost will be the future impact of climate change on our markets and society” (Orsagh, 2020)

Given the range of estimated prices for a 1.5C policy outcome, $40 per BOE net to producers, is a fairly favorable-to-producers interpretation. However, given this favorable price input, the CTx model assumes oil prices stay nominally at $40. This helps keep inputs and comparisons across recent periods more tractable, as this oil price is an approximation. Notably, even adding 2% inflation to the CTx oil price (implemented by changing growth by 2%), would only raise ExxonMobil's valuation to about $26 per share for 2019, still very far from market price of $69.78.

6.1.2. Quantity and growth impacts

Damodaran (2009b) notes fossil fuels are finite resources, that operate as a constraint on “our normal practice of perpetual growth” in terminal value calculations. However, rather than supply, the binding constraint for fossil fuel is the amount of CO2 that the atmosphere can reasonably absorb (i.e., carbon budget).

Fossil fuel demand, even under more optimistic assumptions, is expected to experience very low, or negative, growth. Even pre-pandemic, demand growth was forecast to be roughly 0.5% a year (Birol, 2019; Carbon Tracker, 2020a). According to BP, in a “Business as usual” world: 1) government policies, technologies, and social preferences will cause carbon emissions to peak by mid-2020s and; 2) fossil fuels will fall from 85% of primary energy to 65% in 2050 (Dale, 2020).

The IPCC's Special Report on Global Warming (IPCC, 2018), outlined demand scenario, “P1”, which constrains warming to 1.5C with limited overshooting. For P1, “afforestation is the only carbon dioxide removal option considered”, with no meaningful contribution from CCS technology (a presently non-viable technology in cost and scale), or bioenergy (BECCS). Carbon Tracker analysis indicates a -4.1% annual industry-wide natural decline rate from existing oil projects (Carbon Tracker, 2020d, pp. 15–16), compared to the -6.1% decline required in the P1 scenario. For natural gas, production declines match P1 demand declining -4.5% annually (Carbon Tracker, 2019b.; IPCC, 2018).

Since P1 oil demand falls faster than natural production declines, new project costs must fall below that of existing projects to avoid being stranded (Carbon Tracker, 2020d, p. 15; Carbon Tracker, 2020c). IEA analysis of 1.5C scenarios, found that, “there is very little, if any, justification for adding new oil supply. Essentially production from existing wells is enough to meet demand in a 1.5C scenario” (Gardiner et al., 2021). A 2021 Wood Mackenzie study noted that under a 2C scenario, the “world needs no new oil supply”, as “after 2030, the industry can rely largely on production from assets already on line” (Hittle et al., 2021). The implication is that other than limited maintenance capital expenditures, essentially all new project expenditures should cease (Carbon Tracker, 2020a). Under the IEA's net-zero pathway, which incorporates CCS, low-cost OPEC producers increase their share of declining oil production, implying non-OPEC oil production falls -5.4% annually (IEA, 2021).

Since the CTx valuation is meant to be on a boundary of measuring energy transition impacts, P1, which does not rely on CCS technology, provides better estimates. ExxonMobil's production tilts toward oil, which, under P1, will undergo a steeper decline than gas. As oil is the commodity used for regressions throughout this paper, -6.1% quantity growth is employed for CTx modelling. As discussed later, reducing growth declines to natural gas levels (−4.5% per annum), will not alter the broad conclusions.

6.2. Model assumptions

The DCF models are parsimonious forecasts, as overly complicated models can provide false precision. When the number of estimated terms increases, so does the complexity and error potential. Moreover, as the valuation differences are substantial, modest estimate improvements are unlikely to meaningfully close the gap. As part of this analysis, various detailed valuation scenarios16 were examined, generating modest differences that didn't alter the conclusion - that the market has fundamentally priced in business-as-usual and largely ignored transition risks. Even within a 20% cushion, ExxonMobil's share price, hovering near the BAU valuation, is consistently and significantly higher than the CTx valuation. The Appendix details formulas and Table A outlines assumptions for both approaches.

-

1)

Using a standard 3-year17 DCF model, Free Cash Flow to the Firm (FCFF) is discounted by the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) to result in the Value of Operating Assets. Share value is obtained by subtracting debt, and minority interests, adding cash and dividing by outstanding shares.

-

2)

Historic analysis of ExxonMobil and oil prices begin in 2000, the first post-merger year, and are inflation-adjusted ($ terms, in the valuation year).

-

3)

Commodity companies are essentially “price takers” as even the largest oil companies must sell output at prevailing market prices. The relationship between ExxonMobil's revenues and oil prices is strong (R2 of .808) (Figure 7). This relationship would likely be noisier at a smaller, nascent producer (see Table 1).

| Revenues ($Mlns) = 127,752.4 + 3,103.6 (Average Real WTI Spot Oil Price) |

-

4)

Damodaran (2009b) offers a simple valuation method that employs Exxon's operating income and oil prices. However, as ExxonMobil invested in higher cost projects, its operating margin has continued to shrink. Therefore, a regression of operating income on oil prices alone is insufficient. Rather, a regression of operating margin on oil price and year provides adequate estimates (Adjusted R2 of 0.798) (see Figure 8 and Table 2).

| BAU Operating Margin % = Average Operating Margin since 2000. (Mean Reversion assumption) |

| CTx Operating Margin % = 10.7041 + .0010 ∗ (Average Real WTI Spot Oil Price) - .0053 ∗ Year |

-

5)

The combination of estimated revenues and operating margin provides a strong fit of historic patterns (R2 of .832, Figure 9) and flexibility to model various price and operating margin scenarios.

| Operating Income = Revenues ∗ Operating Margin |

Figure 7.

XOM's revenues, actual and predicted (2019$'s Mlns).

Table 1.

Regression estimates of revenue ($Mlns).

| Observations | 20 | |||

| R2 | 0.808 | |||

| Standard Error | 41,392.8 | |||

|

F-stat |

75.735 |

P-value |

0.0000 |

|

|

Parameter |

Value |

Std. Error |

t Stat |

P-value |

| Constant | 127,752.4 | 27,455.1 | 4.6531 | 0.0002 |

| Avg. Real WTI Spot Oil Price | 3,103.6 | 356.6 | 8.7026 | 0.0000 |

Note: Under CTx assumptions, 2020 Revenues are capped at 2019 ∗ (1 + g), where growth is negative, as an immediate policy response would not boost revenues.

Figure 8.

XOM's operating margin, actual and predicted.

Table 2.

Regression estimates of operating margin %.

| Observations | 20 | |||

| R2 | 0.819 | |||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.798 | |||

| Standard Error | 0.018 | |||

|

F-stat |

38.506 |

P-value |

0.0000 |

|

|

Parameter |

Value |

Std. Error |

t Stat |

P-value |

| Constant | 10.7041 | 1.4264 | 7.5040 | 0.0000 |

| Avg. Real WTI Spot Oil Price | 0.0010 | 0.0002 | 6.2450 | 0.0000 |

| Year | -0.0053 | 0.0007 | -7.4660 | 0.0000 |

Figure 9.

XOM's operating income, actual and predicted (2019$'s Mlns).

The two “paradigms”, while both likely fictions, represent the boundaries of future transition scenarios (Tables 3 and 4, detail DCF figures and share valuations under BAU and CTx, respectively). At year-end 2019, ExxonMobil closed at $69.78 per share.

Table 3.

Business as ususal (BAU) DCF.

|

Expected Free Cash Flow to Firm - XOM | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Business as Usual (BAU) DCF | |||||

| YEAR | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | Terminal Year |

| Rev. growth rate | 1.9% | 1.9% | 1.9% | ||

| Revenues | $255,583 | $352,762 | $359,535 | $366,438 | $373,400 |

| Operating Margin | 4.6% | 10.6% | 10.6% | 10.6% | 10.6% |

| Operating Income ("EBIT") | $11,631 | $37,393 | $38,111 | $38,842 | $39,580 |

| Taxes | $3,059 | $9,834 | $10,023 | $10,216 | $10,410 |

| After-tax Operating Income | $8,572 | $27,558 | $28,088 | $28,627 | $29,171 |

| -Reinvestment (incl Divestiture proceeds) | $5,463 | $11,063 | $11,556 | $12,070 | $7,795 |

| Change in Non-Cash WC | $(1,583) | ||||

| FCFF | $4,692 | $16,495 | $16,532 | $16,557 | $21,376 |

| Terminal Value | $410,261 | ||||

| Present Value | $15,400 | $14,410 | $347,335 | ||

| Return on Capital | 3.4% | 10.6% | 10.4% | 10.1% | 7.1% |

| Capital Invested | $248,616 | $259,679 | $271,235 | $283,305 | |

| Tax rate | 26.3% | 26.3% | 26.3% | 26.3% | 26.3% |

| Cost of Capital (WACC) | 7.1% | 7.1% | 7.1% | 7.1% | 7.1% |

| Value of Operating Assets= | $377,145 | ||||

| + Cash & Other non-operating assets | $3,089 | ||||

| -Debt | $(52,767) | ||||

| -Minority Interest | $(7,288) | ||||

| Value of Equity= |

$320,179 |

||||

| Value per share= | 75.62 | ||||

Note: The BAU Terminal Year ROC has Terminal Value as the denominator.

Table 4.

Carbon tax (CTx) DCF.

|

Expected Free Cash Flow to Firm - XOM | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Tax (CTx) DCF | |||||

| YEAR | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | Terminal Year |

| Rev. growth rate | -6.1% | -6.1% | -6.1% | -6.1% | |

| Revenues | $255,583 | $239,992 | $225,353 | $211,606 | $198,698 |

| Operating Margin | 4.6% | 1.8% | 1.3% | 0.8% | 3.9% |

| Operating Income ("EBIT") | $11,631 | $4,360 | $2,898 | $1,597 | $7,739 |

| Taxes | $3,059 | $1,147 | $762 | $420 | $2,035 |

| After-tax Operating Income | $8,572 | $3,213 | $2,136 | $1,177 | $5,704 |

| -Reinvestment (incl Divestiture proceeds) | $5,463 | $(11,787) | $(22,864) | $(28,823) | $(9,296) |

| Change in Non-Cash WC | $(1,583) | ||||

| FCFF | $4,692 | $15,000 | $25,000 | $30,000 | $15,000 |

| Terminal Value | $113,547.77 | ||||

| Present Value | $14,004 | $21,791 | $116,816 | ||

| Return on Capital | 3.4% | 1.4% | 1.2% | 1.0% | 7.1% |

| Capital Invested | $248,616 | $227,186 | $181,457 | $117,407 | $80,222 |

| Change in BV | $5,463 | $(21,430) | $(45,729) | $(64,050) | $(37,185) |

| Divestiture proceeds/Capital | 55.0% | 50.0% | 45.0% | 25.0% | |

| Divestiture Proceeds ($) | $11,787 | $22,864 | $28,823 | $9,296 | |

| BV Debt | $52,767 | $52,767 | $42,767 | $27,767 | $27,767 |

| BV Debt/ Capital invested | 21.2% | 23.2% | 23.6% | 23.7% | 34.6% |

| Tax rate | 26.3% | 26.3% | 26.3% | 26.3% | 26.3% |

| Cost of Capital (WACC) | 7.1% | 7.1% | 7.1% | 7.1% | 7.1% |

| Value of Operating Assets= | $152,611 | ||||

| + Cash & Other non-operating assets | $3,089 | ||||

| -Debt | $(52,767) | ||||

| -Minority Interest | $(7,288) | ||||

| Value of Equity= |

$95,645 |

||||

| Value per share= | 22.59 | ||||

Note: For CTx, Terminal Year ROC has Terminal Year Capital Invested as the denominator.

7. Discussion

Examining ExxonMobil, valuations do not seem to incorporate a future energy transition. Its share price history reflects the market's worldview resembling continued “business as usual” fossil fuel consumption (Figure 10 charts BAU, CTx valuations and ExxonMobil's share price since 2005). The BAU DCF closely tracks past market values (within 20% in 2005 and 2010 and within 10% in 2015 and 2019, as more post-merger data is employed). The BAU valuation represents 12x P/E,18 and a terminal firm value 14x after-tax operating income. These ratios are in-line with analyst models of terminal values representing 10–20x expected profit (Carbon Tracker, 2020a).

Figure 10.

ExxonMobil's Market Price, and BAU and CTX valuations.

CTx valuations are generally stable with an overall downward trend over the period. Yet, the market price overvaluation relative to the CTx valuation is large, representing 50% equity value at risk, and increasing toward 70% (Figure 11). In part this reflects ExxonMobil's deteriorating operating margins. An additional factor is the impact of delays in implementing an adequate policy response. While a strong, immediate regulatory regime is unlikely, policy delays actually decrease share value due to continued wasted capital expenditures on “stranded assets” and steeper required growth rate declines to achieve net zero. For example, a 2019 “Delay” model shows a further valuation decrease of almost 33% to approximately $15 per share. The “Delay” model relies on BAU cash flows through 2023 and then $40 oil and a steeper growth plunge to match CTx by 2050. The impact of delays on values is further visible in the overall gradual CTx value step downs, largely reflecting shorter time-frames remaining, and therefore steeper required quantity declines.

Figure 11.

ExxonMobil's overvaluation – % equity decline to reach CTx.

Retrospectively, ExxonMobil's share price has been grossly and consistently overvalued (Figure 12). If year-end 2019 (pre-pandemic) is considered the sell date, no acquisition date since 1993 with a long-term hold and reinvested dividends would have matched either the S&P 500 or a 9% annual return. In fact, over that period to obtain a 9% or market return rate through 2019, on a median basis, one should have paid roughly 2/3 rds of market price.

Figure 12.

ExxonMobil's historic overvaluation. NOTE: XOM stock price data obtained from Yahoo finance website (historical “Adjusted Close” prices adjusted for both dividends and splits). SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust (SPY) passively tracks S&P 500 Index, and was used to measure S&P 500 returns with reinvested dividends.

As an additional check, ExxonMobil's 2019 year-end valuations were evaluated with a simple Gordon-growth Dividend Discount Model (DDM) for a stable, mature company (Table 5). Inputs included Net Income, and payout ratio based on Free Cash Flow to Equity (FCFE)/Net Income. ExxonMobil's market price implies perpetual growth at 3.28%, versus expected long-term economic growth of 1.92%, as implied by Treasury bonds. It seems unlikely oil and gas products should grow so much faster than the overall economy. If the T-bond rate of 1.92% is used for growth, ExxonMobil's stock is fairly-priced at $53.49, a 23% discount to 2019 year-end market price. The CTx DCF valuation of $22.59 is consistent with -5.4% growth within the DDM framework, not dissimilar from the -6.1% DCF growth assumption.

Table 5.

ExxonMobil valuation using Gordon Growth Dividend Discount Model.

| Gordon Growth Dividend Discount Model | ||

|---|---|---|

| Stable firm, pays out Dividends equal to its Free Cash Flow to Equity (FCFE) | ||

| Price = D1 / (r-g) , where: | ||

| D1 is next period's dividends, D1 = current Dividends ∗ (1+g); | ||

| r = cost of equity | ||

| g = stable growth rate; typically at or below the growth rate of the economy. | ||

| 2019 Earnings (Net Income) per share | $3.39 | |

| 2019 Assumed Payout Ratio (FCFE/NI) |

94.5% |

FCFE = FCFF - (principal repaid - debt issued) |

|

2019 Dividend paid per share |

$3.20 |

|

| Beta of XOM | 1.174 | |

| Rf rate | 1.92% | |

| Equity Risk Premium |

5.20% |

|

|

Rate (Cost of Equity) |

8.02% |

|

|

Valuation |

Growth Rate |

|

|

Market Year-End 2019 |

$69.78 |

3.28% |

|

Growth equal to Assumed LT Economic Growth (Rf rate) |

$53.49 |

1.92% |

| CTx DCF Value | $22.58 | -5.40% |

Other models and analysis are consistent with a significant decline in ExxonMobil's valuation from an energy transition. In early 2021, Rystad Energy, an independent energy consultancy, released its assessment of an energy transition on various exploration and production companies' upstream portfolios. It found a 30–40% NPV impact to upstream assets, and oil prices effectively $10 lower than without a transition. Rystad determined that 41.7% of ExxonMobil's upstream portfolio value was at risk. The firm had “higher revenue risk than its peers, primarily because its portfolio includes several large, capital-intensive projects such as Permian tight oil and its Guyana assets” (Rystad Energy, 2021a). As of year-end 2019, 68% of ExxonMobil's assets, by book value, were upstream, A rough-cut extrapolation (and after accounting for debt), implies a 33% share price reduction, as of year-end 2019. However, this is a certain underestimate as downstream assets would be meaningfully impacted.

Bloomberg New Energy Finance created a “Bloomberg Carbon Risk Valuation Tool” (Caldecott and Elders, 2013) which runs DCF valuations based on five pre-built energy transition scenarios (Table 6). Overall, these valuations are in-line with the CTx valuation of $22.58 per share (The mean and median of these Bloomberg NEF scenarios is in the $20's per share).19

Table 6.

Bloomberg CRVT scenario values for XOM.

| Bloomberg Carbon Risk Valuation Tool Scenario | XOM DCF Valuation Year-End 2019 |

|---|---|

| 5% annual decrease in oil prices starting from 2020 relative to the futures price | $13.36 |

| $50 a barrel for oil from 2020 | $65.70 |

| $25 a barrel for oil from 2030 | $28.06 |

| Prompt Decarbonization: 80% decrease in EBIT fading in from 2020 and peaking in 2035 | $11.38 |

| Last-Ditch Decarbonization: 80% decrease in EBIT fading in from 2030 and peaking in 2035. | $24.80 |

8. Alternative views

Alternative viewpoints note fossil fuels’ essential economic nature (i.e., demand is nearly perfectly inelastic over short-to-medium periods) and the long “time-frame” before reserves risk being stranded. Yergin and Pravettoni (2016) in an IHS Markit report dismiss a carbon bubble for producers, since their valuations are “based primarily on reserves produced over 10–15 years with no value beyond that”.

The five supermajors have 9–17 years' worth of oil and gas reserves (2019 year-end proved reserves divided by current production, “R/P”), with Exxon at 17 (Toplensky, 2020). However, declining growth, even over long-time frames significantly impacts DCF valuations. The mean-reverting BAU DCF valuation consistently approximates ExxonMobil's stock price (roughly within 8% of actual market value on 12/31/19). It derives roughly 50% of its value after 15 years. In fact, the CTx DCF value equates to full value of BAU cash flows for 11 years and nothing thereafter. To obtain the 2019 year-end share price, 55 years (2019–2074) of the mean-reverting BAU model would be realized, with 0 thereafter. Deviation before 2074 represents downside at 2019 market prices.

Yergin and Pravettoni estimate that proved reserves represent 20% of global oil reserves by volume, but 80% of a firm's market capitalization. According to BP's 2020 Energy Outlook, to reach net zero by 2050, future cumulative oil and gas demand would equal about 50% of current proved reserves (BP, 2020; Newcomb and Jhaveri, 2020). Interestingly, ExxonMobil's 2019 financial statements reported a proved reserves DCF value of $89.9 billion.20 This figure translates into about $21 per share, or $8 if other claims (debt and minority interests) are satisfied first, compared to a year-end share price of about $70.

Yergin and Pravettoni's (2016) timeframe reached out to 2026 to 2031. Now, the transition must be more rapid. Some current projections (BP, 2020; Birol, 2020; Rystad Energy, 2021b; Taplin, 2021) estimate peak oil demand occurred in 2019 or will occur before 2030. Even OPEC's favorable projections indicate annual global growth of less than 0.5%, until oil demand peaks in 2040 (Hodari and Elliott, 2020).21

9. Pandemic impact (2020)

The global pandemic shook world economies and oil and gas producers in particular. Below is a brief evaluation, of this extraordinary year, in which the average WTI spot oil price fell 30% in real terms to just under $40. The pandemic presents a unique circumstance and certainly excessive weight should not be placed on 2020's events going forward. Yet in more ways than can be adequately covered in this article, it did reveal how lower oil and gas prices could impact producers' cash flows and capital decisions. In early 2020, ExxonMobil increased borrowing, and cut its capital expenditures by 30% in order to maintain its dividend (Matthews, 2020a).

ExxonMobil's actual revenues, operating margins and income underperformed model predictions given $40 WTI average spot price (perhaps due to extreme and unanticipated volatility). The firm posted an operating income loss of $10.2 billion, as opposed to the $0.7 billion predicted from inputs. During the year, XOM's share price fell from $69.78 to $41.22.

As of year-end 2020, the CTx DCF estimated a $15.40 per share value, falling 32% from 2019's valuation. As operating income begins from a very negative starting point (even worse than predicted), the firm quickly faces difficult tradeoffs within one-to-two years, as debt cannot easily be staved off by divestitures given large operating losses. The upcoming distress implies that the dividend payments would need to be shifted toward paying down debt. S&P Global downgraded ExxonMobil in March 2020 in part due to increasing leverage and large outflows to fund its dividend (DiLallo, 2020).

Interestingly, the 2020 BAU DCF22, held steady at $75.52, compared to $75.62 a year prior.23 While not entirely surprising given the mean reversion assumptions, there was movement under the surface. Since debt increased $20 billion, and equity market value fell, debt's share of the capital structure doubled from 15% to 29%. Somewhat perversely, increased debt, which has a lower cost of capital than equity, in conjunction with dramatically falling interest rates, outweighed the credit downgrade impact - resulting in WACC falling from 7.1% to 6.2%. This decrease served to boost DCF values, negating modest operating income declines in the future. Moreover, the net impact of changes to the WACC and growth rates24 implied a lower reinvestment rate to reach steady state growth. This reduction in net capital expenditures increases terminal year FCFF.

Unlike observations of past years, XOM's market value was closer to CTx value than BAU. To reach the market share price of $41.22 at year-end 2020 within the BAU model, an implied oil price of $35 would be needed, in conjunction with operating margins mean reverting to almost 10%, and a still positive, but lower 0.9% growth rate. So, while 2020 offered a glimpse of falling price and quantity, there may still be room to fall. It's too early to confirm if the market has begun to meaningfully price energy transition risk or just a short-term pandemic impact. Some of the answer is the continued and significant rise of XOM's stock in early 2021, where energy transition risk would have seemed to increase (greater chance of near-term policy changes) but vaccinations improved short-term outlooks.

Additionally, the market seemed caught off-guard by 2020's write-down announcements (Figure 13). The write-downs25 were often due to the lack of project viability at prices of $40-$55 per barrel of oil, which is slightly above the net to producer price needed to get to 1.5C. Overall, the market reacted negatively, declining by 2% on average relative to the broader energy index; perhaps indicating write-downs due to lower oil prices was unexpected. Notably, ExxonMobil bucked this trend, perhaps since these assets were overdue for a write down.26 The modest relative declines are consistent with the market not fully accounting for transition risk. If it had, one would expect no difference in pricing, or perhaps even an increase, as it would convey management's intention to reduce wasteful capital spending in higher cost projects.

Figure 13.

Write-down relative return impact - O&G Producers vs. Energy Index. ∗Note: Vanguard Energy ETF (VDE) passively tracks the performance of a benchmark index that includes stocks of companies involved in the exploration and production of energy products such as oil, natural gas, and coal.

10. Conclusion: the path ahead

Investors must grapple with climate change and the energy transition. What approach is best: divestment; engagement; ESG-focused screens; or relying on comprehensive risk underwriting and price discipline. Excess returns are produced by exploiting mispricing, often due to the transition from one world state to another. This is not an ESG perspective per se, where good corporate behavior, leads to greater growth or better valuations. The approach here is to evaluate an investment in the face of an upcoming business transition. Divestment may be right on the basis of moral choice; however, these companies are not attractively priced given the transition risk.

One alternative for producers is transition to renewable energy however, such an approach is not without risk. For example, what are a fossil fuel company's competitive advantages in the renewable space? Often incumbents are not well-positioned to transition to a new business model (e.g., Sears versus Amazon). An exception is Orsted, which began in 1973 as the Danish Oil and Natural Gas Company and switched to renewable energy in 2017. Recently Orsted traded “at over three times book value, compared with below par for European supermajors” (Toplensky, 2020). Investors should gage management's nimbleness and capital investment track record in assessing odds for successful repositioning.

Another firm approach, “shrink to profitability”, is consistent with climate budgets, shareholder interests, and the firm's core competencies. If acquired at an attractive price, investors' returns will compensate for a shrinking scope. By cutting costs and capital investment, while maintaining dividend payouts, the returns can be strong as the firm focuses on only its lowest cost prospects.

The more complicated rationale advanced by some institutional investors is to engage while not “sacrificing returns”. If the argument is purely return-driven, they implicitly believe that at current valuations, fossil fuel stocks present attractive return prospects. Simultaneously, these purely return-driven investors claim to use their influence as shareholders to persuade management to substantially change their business products and practices while generating attractive returns (Faust, 2013).27

Often the point will be raised that divesting leads to a narrowed, sub-optimal portfolio set. First, pure divestment, or ESG-screens, may lead to lower returns28 but, the approach here is to divest of over-priced assets. Second, many institutional portfolios contain natural resources as an asset/sub-asset class, which often largely comprises oil and gas producers and/or assets.29 A larger opportunity set is not much help if the worst opportunities are over-weighted.

Finally, market actors, regulators and policymakers can undertake a number of initiatives to remedy the agency, governance and incentive problems that distort markets (Riedl, 2020). First among these is an explicit and adequate carbon price/tax (Nordhaus, 1993). In addition, lending to high transition risk companies should be highly monitored and curtailed to mitigate financial contagion potential (Carney, 2015). Moreover, regulators should require climate-related financial disclosures demonstrating impacts at various carbon budgets to better inform investors.

Investment valuation is an art and a science. Of the two extreme valuation scenarios, ExxonMobil's share price consistently tracks BAU. If one of the mostly widely covered fossil fuel producers is priced near BAU, it provides evidence that fossil fuel producers are overvalued and financial markets have largely ignored transition risk. While CTx assumptions are unlikely to unfold exactly, underwriting should incorporate large measurable externalities (particularly with near-term, identifiable catalysts). While not precluding short-to-medium rallies, this article indicates oil and gas producers present significant downside risk.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Drew Riedl: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Unless otherwise noted, all financial data is sourced from the S&P Capital IQ database and ExxonMobil's financial statements. All stock price data, obtained from Yahoo finance website (historical “Adjusted Close” prices adjusted for both dividends and splits. https://finance.yahoo.com/). Upon request, data is available in Excel format for those who wish to replicate reported results.

For example, from year-end 2009 to year-end 2019 (reinvesting dividends), the S&P 500 (as measured by SPY ETF) returned 13.4% annualized. While ExxonMobil returned 3.5%, Chevron 8.6%, and passively managed Vanguard Energy Index Fund ETF (VDE Ticker) returned 1.9% (Source: Yahoo Financial historic “adjusted close” prices. https://finance.yahoo.com/).

Underwriting reliant upon unsustainable externalities is a fairly pessimistic assumption. “To believe that democracy does not matter as a check on detrimental developments, one would have to argue that the majority of people will be consistently making wrong (or irrational) choices for a long time. This seems unlikely” – (Milanovic, 2019, p. 208).

As an example, refer to ExxonMobil's 2014 report, “Energy and Carbon - Managing the Risks”, in response to a shareholder resolution regarding potential carbon asset risk. https://biotech.law.lsu.edu/blog/Report-Energy-and-Carbon-Managing-the-Risks.pdf, Accessed April 28, 2021.

The run-up in share prices is not a necessary condition for overvaluation. A 5,000 foot fall off a canyon cliff or a mountain peak, is still probably fatal.

Analysts reports within the S&P Capital IQ's database. Long-term economic growth expectations as reflected in the 1.9% Treasury Bond rate.

As Keynes, perhaps apocryphally, said “Markets can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent”.

Based on Bloomberg NEF's LCOE Calculator of electricity, first half 2020 (Carbon Tracker, 2020a).

As of year-end 2019, ExxonMobil had an AA + credit rating and an Altman Z-score of 3.54. Z-scores above 3.0 are generally considered safe credits (Altman, 1968) and AA credit rating companies have historic cumulative default probabilities less than 1% over the next 10 years (Altman and Sabato, 2007).

Source: SP Capital IQ and Chevron financials.

The think-tank Oil Change International using Rystad Energy marginal cost data 2018–2040, incorporating a 10% IRR, determined a long-term equilibrium BOE price between $20 to $35. The 2 °C threshold based on 66% probability. The 1.5 °C threshold assumes a 50% probability (Oil Change International, IEEFA, 2018, Figure 12, Landell-Mills, 2018).

Scenarios evaluated include: utilizing oil futures; 30-year DCF models; various divestment proceeds as a % of book value; and increasing growth rates by 1–2% for the CTx case.

Expected after-tax operating income less anticipated debt costs (adjusting for their after-tax benefit).

To highlight a few of the analytical differences with this paper. Rather than the $40 oil price, Bloomberg NEF's highest valuation utilizes $50 oil prices based on an older analysis (Robins et al., 2013). Additionally, the lowest Bloomberg NEF valuation assumes an 80% EBIT reduction based on McKibben (2012), and the idea that 80% of fossil fuel reserves will stay in the ground. The analysis in this paper assumes ExxonMobil's revenues will fall through natural decline rates and as quantity demanded shrinks through 2050. Moreover, management is assumed to stabilize operating margins by undertaking cost reductions and retaining the most profitable assets so that by 2035, EBIT falls 70%.

The DCF uses the standard accounting 10% discount rate. According to ExxonMobil's own financial statements, as of 2019 year-end, its proved reserves had a discounted cash flow value of about $89.9 billion, representing just 36% of book value of all its' exploration and production, or “Upstream”, assets. On a book value basis, upstream assets represented 68% of the firm's total assets, with downstream and petrochemical comprising the bulk of the rest. Since Exxon was trading at 1.55x on a Price-to-Book, P/B, basis, it would seem that the market is attributing significant value to future exploration and development of reserves.

OPEC assumes the growth will come largely from China and India, despite both being Paris signatories and China's recent pledge to be a net zero economy by 2060 (Hodari and Elliott, 2020; Myers, 2020).

No taxes were imposed in the CTx DCF due to operating income losses. For the BAU DCF, the 2019 effective tax rate was employed but the 2020 net operating losses reduced taxes for 2021.

Employing the futures curve into the 2020 BAU DCF modestly reduced the valuation to around $70/share.

Due to lower long-term economic expectations based on falling Treasury Bond rates from 1.9% to 0.9%.

In 2014, Shell (2014) stated that their stranded asset exposure was minimal due to the decades needed to transform to a less fossil fuel dependent world. Yet on June 30, 2020 and again in late December 2020, Shell wrote down assets. On June 15, 2020, BP wrote-down assets when it moved its long-term price assumption from $70 to $55 per barrel of oil equivalent (BOE). Chevron wrote down $6 billion worth of assets in July. Exxon also announced write-downs near year end 2020.

For example, XTO was acquired by ExxonMobil for $31 billion in 2009, with $2.5 billion written down in late 2017. According to a SEC whistle-blower complaint filed by a former Exxon senior accounting analyst, Exxon should be writing down the book value of XTO by at least $17 billion, representing a roughly 60% write-down (Matthews, 2020b; Matthews and Glazer, 2021).

Paradoxically, they maintain that while they hold enough influence as shareholders to command attention, they simultaneously are too small to influence if they threaten to divest.

However, this can still be justified on moral grounds. Divestment from South Africa by University endowments during Apartheid is an example where risk/return was not a decision driver. That is, without the end of Apartheid, it is unlikely that University endowments would have reentered that equity market simply because the stocks were trading at discounts with strong forward returns.

For example, institutional investors who would be wary of private equity groups focused on a specific industry sector (e.g., retail, defense, etc.) - due to a valid concern that the manager will “force” capital into the sector regardless of valuations - will seek out oil and gas-specific private equity managers.

Fossil fuel production is especially capital intensive, as reflected by Fixed asset turnover ratio (revenue divided by fixed assets). For the last five years Exxon's fixed asset turnover has hovered near 1.0x.

Calculated with Book Value of Debt and Market Value of Equity.

S&P downgraded ExxonMobil from AAA to AA+ in 2016, to AA in 2020, and then AA-in 2021 (Reuters, 2021).

The “terminal year” is NOT the final year of the firm's existence but simply the final year of the projection period. The “terminal year” assumes a repetition of growth and discount rates, with the terminal year's FCFF as the starting point. This allows a present value calculation of Terminal Value so as to capture the value beyond the projection period. 10-year and 30-year projection period DCFs were examined however, in comparison to the 3-year DCF, they tended to depress the CTx values, and add unnecessary complexity. For example, a 3-year DCF assumes ExxonMobil can continue to maintain a high level of FCFF. If the pro forma continues to 10-years, divestments alone would be insufficient to maintain this FCFF. Either debt would increase and/or operating margins would need to significantly recover, conceivably as the remaining asset quality improves. As projection periods increase, a great deal of assumptions on the levers management would have available, and choose, would be necessary. The 3-year approach avoids gaming out management's decisions over 3 + years from now, and avoids potentially overly pessimistic extrapolation. For tractability, and since the discrepancy generally favors ExxonMobil, the 3-year CTx is used.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- Abreu D., Brunnermeier M.K. Bubbles and crashes. Econometrica. 2003;71(1):173–204. [Google Scholar]

- Altman E.I. Financial ratios, discriminant analysis and the prediction of corporate bankruptcy. J. Finance. 1968;23(4):589–609. [Google Scholar]

- Altman E.I., Sabato G. Modelling credit risk for SMEs: evidence from the US market. Abacus. 2007;43(3):332–357. [Google Scholar]

- Altman E.I. second ed. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1993. Corporate Financial Distress and Bankruptcy. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson M., Bolton P., Samama F. Hedging climate risk. Financ. Anal. J. 2016;72(3):13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett M., Brock W., Hansen L.P. Pricing uncertainty induced by climate change. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2020;33(3):1024–1066. [Google Scholar]

- Birol F. International Energy Agency; 2019. World Energy Outlook 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Birol F. International Energy Agency; 2020. World Energy Outlook 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomberg N.E.F. 2019. Electric Transport Revolution Set to Spread Rapidly into Light and Medium Commercial Vehicle Market.https://about.bnef.com/blog/electric-transport-revolution-set-spread-rapidly-light-medium-commercial-vehicle-market/ [Google Scholar]

- Bousso R., Nasralla S. Reuters; 2020. Exclusive: Exxon Set to Revive North Sea Sale after Months of Delays – Sources. June 11. [Google Scholar]

- BP Energy Outlook 2020. https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/business-sites/en/global/corporate/pdfs/energy-economics/energy-outlook/bp-energy-outlook-2020.pdf

- Brower D. Financial Times; 2020. Why ExxonMobil Is Sticking with Oil as Rivals Look to a Greener Future. Oct. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Caldecott B., Elders G. Bloomberg NEF; 2013. White Paper: Bloomberg Carbon Risk Valuation Tool.https://data.bloomberglp.com/bnef/sites/4/2013/12/BNEF_WP_2013-11-25_Carbon-Risk-Valuation-Tool.pdf November 25. [Google Scholar]

- Carbon Tracker . 2019. Nov. “Balancing the Budget: Why Deflating the Carbon Bubble Requires Oil & Gas Companies to Shrink”.https://carbontransfer.wpengine.com/reports/balancing-the-budget/ [Google Scholar]

- Carbon Tracker . 2019. Breaking the Habit.https://carbontracker.org/reports/breaking-the-habit/ Sept. [Google Scholar]

- Carbon Tracker . 2020. Decline and Fall: the Size and Vulnerability of the Fossil Fuel System.https://carbontracker.org/reports/decline-and-fall/ June. [Google Scholar]

- Carbon Tracker . 2020. How the Mighty Are Fallen: How Chasing Growth Destroyed Shareholder Value in ExxonMobil.https://carbontracker.org/reports/exxonmobil-how-the-mighty-are-fallen/ Oct. [Google Scholar]

- Carbon Tracker . 2020. Fault Lines: How Diverging Oil and Gas Company Strategies Link to Stranded Asset Risk.https://carbontracker.org/reports/fault-lines-stranded-asset/ Oct. [Google Scholar]

- Carbon Tracker . 2020. Handbrake Turn: the Cost of Failing to Anticipate an Inevitable Policy Response to Climate Change.https://carbontracker.org/reports/handbrake-turn/ Jan. [Google Scholar]

- Carney Mark. Bank of England Speech; 2015. Breaking the Tragedy of the Horizon - Climate Change and Financial Stability. Sept. 29. [Google Scholar]

- Coady M.D., Parry I., Le N.P., Shang B. Global fossil fuel subsidies remain large: an update based on country-level estimates. Int. Monetary Fund Work. Pap. 2019;19(89):39. [Google Scholar]

- Comerford D., Spiganti A. The carbon bubble: climate policy in a fire-sale model of deleveraging. Centr. Banki. Clim. Change Environ. Sustain. 2016 Nov. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Cornell B., Damodaran A. NYU Stern School of Business; 2020. Valuing ESG: Doing Good or Sounding Good?https://ssrn.com/abstract=3557432 Available at SSRN: [Google Scholar]

- Critchlow K. Mimeo. London School of Economics and Political Science; 2015. Irrational Apathy: Investigating Behavioural Economic Explanations for the Carbon Bubble. [Google Scholar]

- Crowley K., Carroll J. Bloomberg Green; 2020. Exxon Says 20% of Oil, Gas Reserves Threatened by Low Prices.https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-08-05/exxon-20-of-its-oil-gas-reserves-threatened-by-low-prices August 6. [Google Scholar]

- Crowley Kevin. World Oil; 2021. Exxon Takes Canadian Oil Sands off its Books in Historic Reserves Revision.https://www.worldoil.com/news/2021/2/25/exxon-takes-canadian-oil-sands-off-its-books-in-historic-reserves-revision Feb., 25. [Google Scholar]

- Dale S. 2020. BP Energy Outlook 2020, Presentation with Script.https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/business-sites/en/global/corporate/pdfs/energy-economics/energy-outlook/bp-energy-outlook-2020-presentation-with-script.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Damodaran A. 2009. Valuing Declining and Distressed Companies.https://ssrn.com/abstract=1428022 June. Available at SSRN: [Google Scholar]

- Damodaran A. 2009. Ups and Downs: Valuing Cyclical and Commodity Companies.https://ssrn.com/abstract=1466041 Sept. Available at SSRN: [Google Scholar]

- DiLallo M. 2020. Exxon Mobil's Credit Rating Downgraded a Notch by S&P.https://www.nasdaq.com/articles/exxon-mobils-credit-rating-downgraded-a-notch-by-sp-2020-03-16 Available at: Nasdaq, March 16. [Google Scholar]

- Faust . 2013. Fossil Fuel Divestment Statement.https://www.harvard.edu/president/news-faust/2013/fossil-fuel-divestment-statement/ October 3. Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner D., Sullivan R., Dietz S., Valentin J. 2021. The Oil and Gas Industry Will Need to Scale Back Much Faster to Limit Warming to 1.5C.https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/businessreview/2021/02/10/the-oil-and-gas-industry-will-need-to-scale-back-much-faster-to-limit-warming-to-1-5c/ Feb. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Gennaioli Nicola, Shleifer Andrei. What comes to mind. Q. J. Econ. 2010;125(4):1399–1433. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin P.A., Jaffe A.M., Lont D.H., Dominguez-Faus R. Science and the stock market: investors’ recognition of unburnable carbon. Energy Econ. 2015;52:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hittle A., Odoardo M., Gelder A., Mielke E. Wood Mackenzie; 2021. Reversal of Fortune: Oil and Gas Prices in a 2-degree world.https://www.woodmac.com/horizons/reversal-of-fortune-oil-and-gas-prices-in-a-2-degree-world/ April. [Google Scholar]

- Hodari D., Elliott R. Peak oil? OPEC says the world’s richest countries are already there. Wall St. J. 2020 Oct. 8. [Google Scholar]

- IEA . IEA; Paris: 2021. Net Zero by 2050.https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-by-2050 [Google Scholar]

- IEA and the Imperial College’s Centre for Climate Finance & Investment . 2020. Energy Investing: Exploring Risk and Return in the Capital Markets.https://imperialcollegelondon.app.box.com/s/f1r832z4apqypw0fakk1k4ya5w30961g June. [Google Scholar]

- Ilhan E., Sautner Z., Vilkov G. Carbon tail risk. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2021;34(3):1540–1571. [Google Scholar]

- In S.Y., Park K.Y., Monk A. Is ‘being green ‘rewarded in the market? an empirical investigation of decarbonization risk and stock returns. Int. Assoc. Energy Econom. (Singapore Issue) 2017;46:48. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC . 2018. Global Warming of 1.5ºC Summary for Policy Makers.https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2019/05/SR15_SPM_version_report_LR.pdf October 2018. Available at. [Google Scholar]

- Jakab S., Lee J. Exxon: Heavy lies the dividend crown. Wall St. J. 2021 May 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp J. Reuters; 2020. Global Energy Transition Already Well Underway. Sept. 11. [Google Scholar]

- KPMG . KPMG International; The Netherlands: 2008. International Survey of Corporate Responsibility Reporting 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Krauss C. New York Times; 2020. Oil Companies on Tumbling Prices: ‘Disastrous, Devastating. March 31. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger P., Sautner Z., Starks L.T. The importance of climate risks for institutional investors. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2020;33(3):1067–1111. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Xin W., Zhang C. 2019. Climate sensitivity and predictable returns. Available at SSRN 3331872. [Google Scholar]

- Landell-Mills Natasha. Sarasin &Partners; 2018. Are Oil and Gas Companies Overstating Their Position?https://sarasinandpartners.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/NLM-Are-oil-and-gas-companies-overstating-NB.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Litterman Robert. Pricing climate change risk appropriately. Financ. Anal. J. 2011;67:4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Litterman Robert. Ensia Magazine; 2013. The Other Reason for Divestment. November 5. [Google Scholar]

- Luhavalja A. S&P Global Market Intelligence; 2020. Exxon Could Step up Divestitures, Write Down $30B in Gas Assets. Oct. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Luntz Frank. 2019. National Survey Results on the Climate Leadership Council’s Carbon Dividend Plan.https://www.clcouncil.org/media/Luntz-Carbon-Dividends-Polling-May-20-2019-FINAL.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Marlon J., Howe P., Mildenberger M., Leiserowitz A., Wang X. Yale Program on Climate Change Communication; 2020. Yale Climate Opinion Maps 2020.https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/visualizations-data/ycom-us/ Sep. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews C. Wall Street Journal; 2020. Exxon Cuts Capital Spending by 30% in Response to Coronavirus. April 7. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews C. Exxon Mobil resists write-downs as oil, gas prices plummet. Wall St. J. 2020 June 30. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews C., Glazer E. Exxon draws SEC probe over permian basin asset valuation. Wall St. J. 2021 Jan. 15. [Google Scholar]

- McKibben B. Rolling Stone; 2012. Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math.http://www.rollingstone.com/politics/news/global-warmings-terrifying-new-math-20120719 [Google Scholar]

- Milanovic B. Harvard University Press; 2019. Capitalism, Alone: the Future of the System that Rules the World. [Google Scholar]

- Myers S.L. New York Times; 2020. China’s Pledge to Be Carbon Neutral by 2060: what it Means. Sept. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Naqvi M., Burke B., Hector S., Jamison T., Dupre S. 2017. All Swans Are Black in the Dark. How the Short-Term Focus of Financial Analysis Does Not Shine Light on Long-Term Risks. Tragedy of Horizon Report. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb J., Jahveri K. Rocky Mountain Institute; 2020. The Map Is Not the Territory: New Routes to a 1.5°C Future. October 9. [Google Scholar]

- NOAA . Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters; 2021. National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) U.S.https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/billions/ [Google Scholar]

- Nordhaus W.D. Optimal greenhouse-gas reductions and tax policy in the" DICE" model. Am. Econ. Rev. 1993;83(2):313–317. [Google Scholar]

- Oil Change International, IEEFA . 2018. Off Track – How the International Energy Agency Guides Energy Decisions towards Fossil Fuels Dependence and Climate Change.http://priceofoil.org/content/uploads/2018/04/Off-Track-IEA-climate-change1.pdf April. [Google Scholar]

- Orsagh M. CFA Institute; 2020. Climate Change in the Investment Process.https://www.cfainstitute.org/-/media/documents/article/industry-research/climate-change-analyis.ashx Available at. [Google Scholar]

- Reber R., Winkielman P., Schwarz N. Effects of perceptual fluency on affective judgments. Psychol. Sci. 1998;9(1):45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Reuters . 2021. S&P Downgrades Exxon and Chevron on Climate Risk, Dour Earnings.https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-oil-credit/sp-downgrades-exxon-and-chevron-on-climate-risk-dour-earnings-idUSKBN2AC29C Feb. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Riedl D. Why market actors fuel the carbon bubble. The agency, governance, and incentive problems that distort corporate climate risk management. J. Sustain. Fin. Invest. 2020:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Robins N., Mehta K., Spedding P. HSBC Global Research; 2013. Oil & Carbon Revisited: Value at Risk from Unburnable Reserves. [Google Scholar]