Abstract

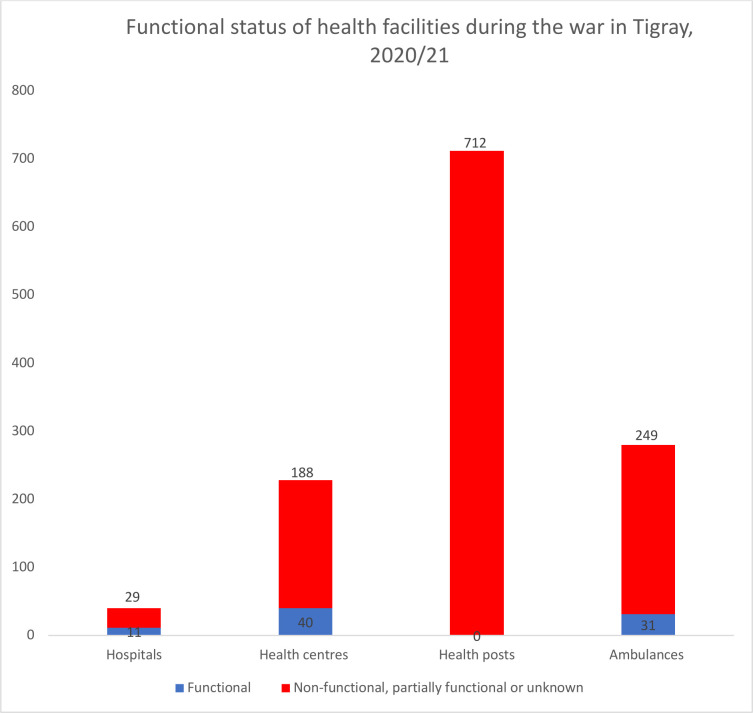

The war in Tigray region of Ethiopia that started in November 2020 and is still ongoing has brought enormous damage to the health system. This analysis provides an assessment of the health system before and during the war. Evidence of damage was compiled from November 2020 to June 2021 from various reports by the interim government of Tigray, and also by international non-governmental organisations. Comparison was made with data from the prewar calendar year. Six months into the war, only 27.5% of hospitals, 17.5% of health centres, 11% of ambulances and none of the 712 health posts were functional. As of June 2021, the population in need of emergency food assistance in Tigray increased from less than one million to over 5.2 million. While the prewar performance of antenatal care, supervised delivery, postnatal care and children vaccination was 94%, 73%, 63% and 73%, respectively, but none of the services were likely to be delivered in the first 90 days of the war. These data indicate a widespread destruction of livelihoods and a collapse of the healthcare system. The widespread use of hunger and rape during the brutal war and the targeting of healthcare facilities seem to be key components of the war. To avert worsening conditions, an immediate intervention is needed to deliver food and supplies and rehabilitate the healthcare delivery system and infrastructure.

Keywords: epidemiology, public health, infections, diseases, disorders, injuries

Summary box.

Large-scale full-fledged civil wars, such as the one in Tigray where foreign forces from Eritrea were involved, cause significant infrastructural damage, and enormous consequences on the physical, mental and psychosocial health of millions of people.

This is the first analysis to report the damage comprehensively and systematically to the health system in Tigray because of the ongoing war in Tigray.

The war has led to unprecedented and significant attrition of health workers, reduction in maternal and child health services and increase in rates of malnutrition, burden of infectious and non-infectious illness and gender-based violence.

The proper quantification of infrastructural damage and, measurement of key indicators in comparison to the prestate situation is critical to the short, medium and long-term postwar recovery and reconstruction plans.

Introduction

Tigray is one of the ten regional states of Ethiopia, with a population of 7.3 million in 2021 based on the 2007 Ethiopian housing and population census.1 Since 4 November 2020, the Tigray regional state in Northern Ethiopia has faced a devastating armed conflict.2 The occupying forces that entered and ravaged Tigray via military campaign (hereafter referred to as Ethiopian government allied invading forces unless mentioned individually) are the Ethiopian National Defence Forces ENDF (from east, southeast and south), Amhara special forces and Amhara militia (south and southeast), and Foreign Eritrean army (across the northern border). The forces fighting on behalf of the Tigray Regional government and people are called Tigray Defence Forces (TDF).3 As a result of the war, it is estimated that more than 52 000 civilians have been killed, 2.3 million people displaced, while 70 000 people have crossed to the neighbouring Sudan in the first 3 months of the war.3 In addition, 7 months in to the war, the World Food Programme reported that 91% of the region’s population required emergency humanitarian assistance.4 Many have reported that the deliberate destruction, vandalisation and looting of the entire health system have been the hallmarks of the ongoing conflict.2 5 6

In this analysis, we examined the extent of the health system collapse between November 2020 and June 2021 (the war is still ongoing) and made comparisons with the previous year (prewar state). The Global Society of Tigray Scholars and Professionals7 brought together the members of this team and helped to coordinate the activities to compile evidence on the extent of the health crisis due to the war. Accordingly, we: (1) reviewed reports from the Tigray Regional Health Bureau (the then Tigray interim administration) and (2) mapped opinion pieces, press releases and humanitarian situation updates from major multilateral organisations such as from the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA), UNICEF, WHO, USAID, from November 2020 to June 2021. We then compared the current status (during-war) with the 2019 health performance of the region (prewar). The prewar data we used for comparison were obtained from: (1) unpublished 2019 report of the Tigray regional Health Bureau8 and (2) latest Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey report.9

From the above data sources, we compiled: (1) functional status of health facilities, (2) functional status of ambulances, (3) number and employment status of health workers, (4) antenatal care (ANC), (5) delivery care, (6) postnatal care, (7) immunisation, (8) malnutrition, (9) food insecurity, (10) rape and gender based sexual violence, (11) non-communicable diseases (NCDs), (12) chronic infectious illnesses and (13) outbreak status of selected ailments. We then categorised the status of healthcare performance into four main themes: attacks on healthcare facilities and the attrition of health workers; the maternal and child health services and malnutrition; chronic non-infectious and infectious diseases and outbreaks; and gender based sexual violence and rape.

Attacks on healthcare facilities and attrition of health workers

Before the war, Tigray had three tiers of health system: primary healthcare unit which includes health posts, health centres and primary hospitals; secondary care provided by general hospitals; and tertiary care served by specialised referral hospitals. There were two specialised hospitals, 16 general hospitals, 29 primary hospitals, 233 health centres and 712 health posts in the region. A health post, staffed by two community health extension workers (HEWs) implementing the health extension programme (HEP), is the lowest health institution structure in the rural areas and is designed to serve one kebele (the smallest administrative unit in Ethiopia). Five Kebeles (five health posts) form a catchment area for a health centre catering to 15 000–25 000 rural or 40 000 urban population.

Prior to the war, there was also a functional healthcare financing system in the region, a system which implemented revenue retention used at health facility level, systematised fee-waiver system for the poor, standardised exemption services, set and revised user fees, introduced a private wing in public hospitals, outsourced nonclinical services and promoted health facility autonomy through the introduction of a governance system. Health information systems, electronic records of patient data, were also functional at each health centre and hospital. There were 280 functional ambulances facilitating the referral system in 2019/2020 of which 59% were serving mothers going into labour. These were fully functional before the breakout of the war.

After the onset of the war, a report by the Health Bureau of the Interim Tigray Administration10 revealed that the HEP has become completely non-functional. The status of the community HEWs who were in charge of the HEP became unknown, with their salaries completely cut-off, and their safety not guaranteed. This is important due to the rampant incidents of sexual violence in the region, given that almost all HEWs are women. Two-thirds of the Woreda Health Offices in the region became non-functional, while the status of the remaining one third (south Tigray, southeast, western and some part of eastern Zones) is unknown as they were under the control of the occupying Eritrean and/or Amhara forces.

Figure 1 describes the average functionality of hospitals and health centres during the war. Out of the assessed 40 hospitals, 14 were non-functional, nine were partially functional although with severe limitations, and 11 were fully functional but the status of the remaining six was unknown11 as they were still under the occupation of the Amhara forces and militia.10 Out of the assessed 228 health centres in the region, only 40 (17.5%) were functional, while the remaining were either completely non-functional, partially non-functional or their status was unknown due to occupation by the Amhara or Eritrean forces.10 The whereabouts of 90% of the 280 ambulances which have been serving before the onset of the war is unknown.11

Figure 1.

Functional status of health facilities during the war in Tigray, 4 November 2020 to 24 February 2021—figure 1 describes the functional status of health facilities during the war in Tigray, 4 November 2020 to 24 February 2021.

Before the war excluding the two referral hospitals in Ayder (Mekelle) and Axum which are administered by the federal government, there were a total of 19 324 health workers including specialist physicians (69), general practitioner physicians (411), nurses (4402), midwives (1394), pharmacists (296), laboratory specialists (494), health officers (935), public health specialists (43), HEWs (1918), supportive staffs (5344) and others (4018). After the onset of the war, more than 50% of members of the regional health work force were unable to report to their working institutions.10 The interim government report10 revealed that a total of 2000 healthcare workers were reportedly registered in internally displaced people camps in the capital city, Mekelle, as of May 2021. As described by several international organizations and media outlets including the MSF12 the intentional damage of healthcare facilities in Tigray as a potential weapon of war with deliberate destruction and looting has led to displacement of thousands of healthcare workers including death of more than ten workers.

Following the war, the healthcare financing programme (including community-based health insurance) has collapsed completely, and people cannot afford to pay for medical services even when there is access to medical care.10 The health information system has totally collapsed across the region as majority of the tools such as computers and hard-copy medical records are looted or destroyed.10 There is an added obstacle against a rapid flow of information as the region still remains in a total internet and other communications blackout.

Maternal and child health services, and malnutrition

Before the war, 94% of women in Tigray had access to ANC (vs 74% of the national average), 73% of mothers benefited from skilled delivery (vs 48% of the national average), and 63% received postnatal care services (vs 33.8% of the national average).8 9 Moreover, 73% of children received all basic vaccinations, and 83% of children received measles vaccination,8 compared with the respective 39% and 54% of the national average.9 After the war, virtually the entire MCH service was collapsed and none of the services above were available.5 In addition, 85% of the health centres and 70% of the hospitals are partially or completely non-functional leaving only 15% of health centres and 30% of hospitals to provide services to mothers and children.10

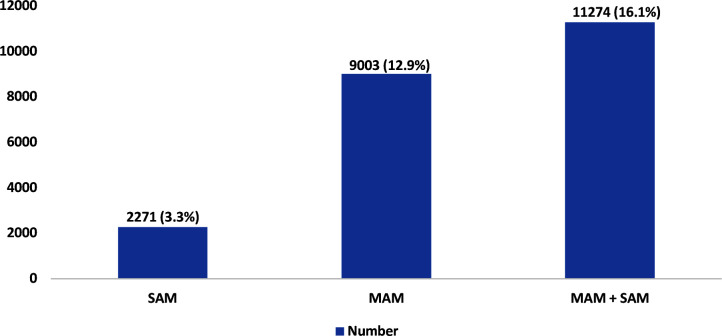

The impact of the all-out war on child malnutrition and food insecurity has been staggering. Before the war, there were 600–950 thousand food insecure people in Tigray.13 14 In a recent report during the war, the World Food Programme reported that 5.2 million people (91% of the total population in the region) are food insecure requiring immediate humanitarian assistance, of which 1.2 million people women and children will be assisted with nutritionally fortified food by WFP.4 UNICEF revealed that the level of severe acute malnutrition (SAM) in Tigray in January 2021 was three times of the global WHO emergency threshold, putting 70 000 children at risk.15 The twelve weeks combined malnutrition is described in figure 2. Moreover, as of May 2021, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) found that 26.6% of 309 children screened in mobile clinics at several locations in Northwest Tigray were malnourished and 6% of them were severely acutely malnourished, leading them to conclude this ‘warrants immediate action’.16

Figure 2.

SAM (severe acute malnutrition) and MAM (moderate acute malnutrition) in Tigray, 2021—figure 2 describes the malnutrition status of children in Tigray.

Chronic non-infectious and infectious diseases, outbreaks and diseases surveillance system

Reports from Tigray Regional Health Bureau show that the estimated 1 80 000 patients with chronic communicable and non-communicable diseases in the region, including 24 000 with diabetes, 20 000 with hypertension, 43 000 with HIV and more than 1500 with active tuberculosis, have missed clinical follow-ups and disease management plans in the first 3 months of the war.10 Moreover, MSF17 and other orgaizations5 18 also revealed that chronically ill patients have missed routine clinical follow-ups. Although there is no reported outbreak to date, given the collapse of the healthcare system, interruption of childhood vaccination, poor sanitation and massive internal displacement, common outbreaks such as cholera, measles, malaria, yellow-fever and COVID-19 are likely to arise or worsen. There are reports from the WHO which indicate signs of acute watery diarrhoea cases in different towns of Tigray19 such as Adwa, Bora, Selewa and Negsege.10 Moreover, the then interim government of Tigray reported 880 cases of eye disease (bacterial conjunctivitis) outbreak from Edaga-Arbi town. In general, the disease surveillance system, as with the overall healthcare system, has been severely destroyed. As per the interim government’s report, the early warning and response system across Tigray region is destroyed, although there were attempts to restore it in 44 health facilities. There are also many anecdotal reports of patients with insulin dependent diabetes dying after they run out of their insulin supplies.

Gender-based sexual violence and rape

Sexual violence and abuse, including rape cases appear to be on an alarming scale. The issue has gained international attention and has been widely reported.20–22 A political figure in United Kingdom, during a debate in the United Kingdom Parliament on Tigray war on 25 March 2021 stated that an estimated 10 000 girls and women were raped in the first five months of the war.20 The USAID23 also released a detailed document on its analysis report using a sample of 36 reported incidents of sexual violence among victims including 106 women and girls by 144 different perpetrators during the period of November 2020 and March 2021. The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) report found that 39% of victims reported being raped inside their homes, and 33% of them were gang-raped.23 Moreover, 44% and 33% of the victims were raped by Ethiopian and Eritrean soldiers respectively, 6% by Amhara Militia, 6% by combinations of Ethiopian and Eritrean soldiers, and 11% did not know who raped them.23 The New York Times released a story of an 18 years old girl who lost her limbs while defending herself against the perpetrators, identified as Ethiopian and Eritrean solders.21 Amnesty international24 revealed that health facilities in Tigray recorded 1288 cases of gender-based violence between February and April 2021. Adigrat Hospital alone recorded 376 rape cases from the beginning of the conflict to the 9 June 2021.

Ongoing responses

As the war is still ongoing and Tigray is under complete siege and communication blackout, it is difficult to gather the evidence related to response strategies. Even though the Ethiopian ministry of health with its partners has attempted to deliver limited medicines and vaccines, the delivery was blocked or looted by the allied forces.10 There are news reporting emergency responses by international humanitarian organisations. MSF’s mobile clinics16 were implemented as an alternative response, until suspended by the Federal government.25 Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) used to support refugees at Hitsats and Shimelba refugee camps in Tigray until the federal government suspended it.25 NRC used to support about 33 000 Eritrean refugees in Tigray, who later were forced to flee the camps at the onset of the conflict.25 Other humanitarian organisation such as the UNAID and other UN agencies were responding to crisis by refilling medications and providing therapeutic food for malnutrition. Even though the UN agencies and other international humanitarian organisations continued to respond using any window of opportunity they got, the support was not enough to fulfil Tigray’s urgent need, due to the obstruction of transport access to Tigray imposed by the Ethiopian federal government.

As to the role of Tigray’s government, as of June 2021, though nominally the regional and zonal governments have returned to their positions, they have to deal with a near total destruction of the health system and are not in a position to completely restore it. In addition, many of the woredas and kebeles are out of reach of the interim government due to the ongoing war. We believe the administrative structure of many health facilities has been restored, and many of the healthcare workers have returned, but the government does not have cash to pay their salaries. In addition, due to the defacto blockade and siege imposed on the region, no medications and medical equipment can enter Tigray and therefore the facilities could not be made functional.

Implications

Tigray, once touted as a region with one of the best healthcare systems in Ethiopia,9 now has a collapsed healthcare system. The reality facing the people of Tigray is a shattered health system, unknown but scary burden of diseases, unattended trauma due to widespread use of rape as a weapon, displacement crises– all painting a very dire situation. Despite international humanitarian law which states that healthcare facilities ought to be protected during an armed conflict, reports by reputed organisations including MSF, UNOCHA and others indicate that the Ethiopian army, Eritrean army, and Amhara militia deliberately attacked the health facilities and professionals, looted equipment, and converted some of them into military camps. Thus, the complete non-functionality of the HEP and district health offices, the partial or complete non-functionality of 85% of health centres and 70% of hospitals, the limited supply to the functional hospitals and health centres, and the substantial attrition of health workers, ranging from HEWs to specialist physicians, show the total collapse of the health system in Tigray.

The complete non-functionality of HEP has several implications for Tigray, a region which was the first to launch the programme in 2003 and had been one of the best performers in Ethiopia until the outbreak of the war.9 HEWs were the pillars of the healthcare system contributing significantly to maternal and child health programmes in the region.26 27 For example, a study in Tigray revealed that HEWs provided family planning related information to 72% of mothers, and ANC, delivery, and PNC services to 44%, 26% and 4%, respectively.26 The HEWs had critical role in chronic disease management including HIV, tuberculosis and education of personal hygiene.28

In Tigray, virtually all health posts, three out of four hospitals and four out of five health centres are non-functional as result of the war. The documented widespread destruction of healthcare facilities has profound implications on the healthcare services and the health of the people of Tigray now and in the future. Internal and external displacements of millions living in besieged areas, countless attacks on various medical facilities, and brain drain of healthcare workers are increasing at an alarming rate and will have profound and long-lasting impact on the healthcare delivery system. Above all, the conflict is being increasingly characterised by violations of international humanitarian laws, and disregard for the protection of health workers against international humanitarian laws, leading to further attrition and loss of critical manpower needed for recovery.

Harrowingly, 91% of the total population in Tigray now needs emergency assistance. There have been reports by international media that Ethiopian government allied forces are burning or looting cash crops, are denying farmers the chance to farm their lands and/or collect their harvests and killing or looting their domestic animals including oxen (the backbone of livelihood traditional farming in Tigray), making the future prospects for the region alarmingly dire. Similar reports in other armed conflict areas have also shown the worsening of food insecurity during and after similar atrocities. For example, an estimated 14·4 million people were unable to secure their food needs and about 0.37 million children were suffering from severe malnutrition in Yemen.29 While the short-term effects of malnutrition are death, failure to thrive and stunting (irreversible height loss), SAM adversely affects educational performance, cognitive development, and negative impacts on broad economic parameters.30 In sub-Saharan Africa, poor cognitive functioning and increased healthcare costs associated with stunting costs the region about 2%–3% of economic growth.31 Accordingly, in the long term, we may be looking at an increased financial burden on the region’s healthcare system and its economy.

Evidence shows that there is a risk of exacerbation or emergence of new outbreaks during an ongoing war, and our analysis revealed the likelihood of outbreaks such as COVID-19, measles, malaria and other illnesses. Polio in Syria,32 and cholera in Yemen and Rwanda33 were examples of outbreaks in armed conflict areas. Our study also found that significant number of NCDs patients were interrupted from their regular follow-up. Discontinuation of regular follow-ups and interruptions in refill of drug of these patients for an extended period carries the risk of disease progression, drug resistance, and increased transmission of disease for communicable illnesses—all potentially leading to death, and therefore can be used as a surrogate for morbidity and mortality.

Finally, we would like to acknowledge that the war is still ongoing and the conflict has expanded beyond the borders of the Tigray region into Afar and Amhara regions. However, the scope of our analysis and discussions is limited to the first 8 months of the war, before June 2021—which mainly involved at that time the Tigray region. The primary and senior authors of this paper, however, have highlighted the issue in the recent piece published at The Conversation.34

Evidence also shows that there is a lack of post-war baseline data in war torn areas. Recent responses to humanitarian emergencies in Syria, Yemen and Rohingya are some of examples of conflicts of similar nature, even though the scale and intensity of the conflicts vary greatly.35 36 In Syria and Yemen, there were shortcomings of baseline health system data, weak public health information systems, and interrupted data collection system making the humanitarian response challenging.35 36 Hence, this study will contribute to Tigray’s future recovery plans as a baseline.

Limitations

The assessment of the impact of civil war on health, nutrition and health services are fraught with difficulties.35 37 Without exception, data and statistics are political and humanitarian tools for all parties directly or indirectly involved in an armed conflict. Massive displacement of people and lack of access to insecure areas are just a few consequences of war that further hamper objective assessment of the situation. The assessment of the situation in Tigray suffers from similar limitations. Yet, the consistency and breadth of information summarised in our paper are an important indication of the devastating impact of the conflict on Tigray’ health services and system which was functioning very well prior to the war.

Conclusions

In summary, the loss of healthcare manpower and damaged infrastructure will have a lasting consequence in rehabilitating the healthcare system of Tigray once the war is over. In addition, a complete blackout of communications, as well as complete interruption of electricity, and banking services exacerbates the problem and the ability to accurately understand it—severely limiting the capacity to provide help. Furthermore, the well documented intentional denial of access to international humanitarian aid including food, the widespread use of rape and sexual harassment, possibly as a systemic weapon of war, and the occurrence of widely reported ethnic cleansing and atrocities throughout Tigray pose additional challenges to the healthcare delivery and healthcare systems in Tigray. Co-operative international push to stop the collective punishment of Tigray should be of the highest priority in order to open up basic public services including healthcare.

The focus of WHO for the past several months has been understandably on COVID-19 prevention and control. Maybe as result of that, the health crisis emanating from the Tigray war did not get the necessary attention that it deserves. Even though it was late in happening, WHO has already declared its grave concern about the humanitarian and health crises in Tigray.38 This implies the need for WHO to apply every effort to support the collapsed health structure in the region. The findings from the current study will strengthen local and international actors’ responses to the humanitarian health emergencies amid the protracted conflict. Noting the plight of Tigrayan civilians, individual health professionals and researchers working with children, women and men, and in local, national and global professional medical/public health organisations, should use their powerful collective voices to lobby the Ethiopian and Eritrean governments for enforcement of international humanitarian laws.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge GSTS for bringing together this team of experts to conduct the study and prepare this analysis paper.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Twitter: @Azebdej

Presented at: All authors are members of the Global Society of Tigray Scholars and Professionals (GSTS).

Contributors: HG, KB, ESS, DS, MG, YGG, SAG, FA, AGT, MA, SG, AS and FHT conceived the idea. YGG and FA participated in the interim report preparation and provided relevant data from the report for this study. HG and FHT searched and compiled all other relevant reports, and HG drafted the manuscript. All authors critically review and approve the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Data were extracted from publicly available reports and ethics approval was not required.

References

- 1.World Population Review . Ethiopia population 2021: world population review, 2021. Available: https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/ethiopia-population [Accessed 01 Feb 2022].

- 2.Devi S. Tigray atrocities compounded by lack of health care. Lancet 2021;397:1336. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00825-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plaut M. The International community struggles to address the Ethiopian conflict. RUSI Newsbrief RUSI, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 4.WFP . WFP Ethiopia Tigray Emergency Response: Situation Report #1. Rome, Italy: World Food Program, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tesfay FH, Gesesew HA. The health crisis in Ethiopia’s war-ravaged Tigray. Ethiopoan Insight, 2021. Available: https://www.ethiopia-insight.com/2021/02/24/the-health-crisis-in-ethiopias-war-ravaged-tigray/ [Accessed 4 Apr 2021.].

- 6.MSF . People left with few healthcare options in Tigray as facilities looted, destroyed: Médecins sans Frontières (MSF), 2021. Available: https://www.msf.org/health-facilities-targeted-tigray-region-ethiopia [Accessed 4 Apr 2021].

- 7.GSTS . Global Society of Tigray Scholars & Professionals, 2018. Available: http://scholars4tigrai.org/ [Accessed 19 May 2021].

- 8.TRHB . Tigray regional health bureau II ten years health Bulletin (EFY 1998-2007 or 2006/7-2014/5). Mekele, Tigray, Ethiopia: Tigray Regional Health Bureau (TRHB), 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI) [Ethiopia] and ICF . Ethiopian mini demographic health survey 2019. key indicators. Rockville, Maryland, USA: EPHI and ICF, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tigray Regional Health Bureau . Health care crisis in a war ravaged Tigray. Unpublished Report, 2021.

- 11.Reuters . Update 2-'People die at home': Tigray medical services struggle after turmoil of war, 2021. Available: https://www.reuters.com/article/ethiopia-conflict-health-idUSL1N2KE11S 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32669-6 [DOI]

- 12.MSF . People left with few healthcare options in Tigray as facilities looted, destroyed, 2021. Available: https://www.msf.org/health-facilities-targeted-tigray-region-ethiopia [Accessed 15 Mar 2021].

- 13.Devi S. Humanitarian access deal for Tigray. Lancet 2020;396:1871. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32669-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.OCHA . Ethiopia- Tigray region humanitarian update. Geneva: United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 15.UNICEF . Tigray’s children in crisis and beyond reach, after months of conflict: UNICEF, 2021. Available: https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/01/1083102#:~:text='70%2C000%20children%20at%20risk'&text=According%20to%20UNICEF%2C%20within%20Tigray,%E2%80%9D%2C%20Ms.%20Fore%20maintained [Accessed 20 May 2021].

- 16.MSF . ‘Alarming’ malnutrition in Ethiopia’s war-hit Tigray: Doctors Without Borders, 2021. Available: https://english.alarabiya.net/News/world/2021/05/05/-Alarming-malnutrition-in-Ethiopia-s-war-hit-Tigray-Doctors-Without-Borders [Accessed 20 May 2021].

- 17.MSF . Widespread destruction of health facilities in Ethiopia's Tigray region, 2021. Available: https://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/what-we-do/news-stories/news/widespread-destruction-health-facilities-ethiopias-tigray-region [Accessed 20 May 2021].

- 18.Tesema A. Food and healthcare in war-torn Tigray: preliminary insights on what’s at stake Canberra, Australia: The Conversation, 2021. Available: https://theconversation.com/food-and-healthcare-in-war-torn-tigray-preliminary-insights-on-whats-at-stake-153021 [Accessed Apr 2021].

- 19.Schlein L. WHO Warns of diseases spreading in Tigray because of conflict, 2021. Available: https://www.voanews.com/africa/ethiopia-tigray/who-warns-diseases-spreading-tigray-because-conflict?amp=&__twitter_impression=true&s=07&fbclid=IwAR2TMP7hGMSqiSwezU9ZZs8lBDA8ql8FH4wmmSurAMfBmHGb2Iz2ein7t3o [Accessed 20 May 2021].

- 20.Helen H. 2021 speech on the Tigray region of Ethiopia London, United Kingdom, 2021. Available: https://www.ukpol.co.uk/helen-hayes-2021-speech-on-the-tigray-region-of-ethiopia/ [Accessed 04 Apr 2021].

- 21.The New York Times . ‘They Told Us Not to Resist’: Sexual Violence Pervades Ethiopia’s War, 2021. Available: https://us.newschant.com/world/they-told-us-not-to-resist-sexual-violence-pervades-ethiopias-war/ [Accessed 20 May 2021].

- 22.Aljazeera . ‘A Tigrayan womb should never give birth’: Rape in Tigray, 2021. Available: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/4/21/a-tigrayan-womb-should-never-give-birth-rape-in-ethiopia-tigray [Accessed 20 May 2021].

- 23.USAID . Sexual Violence in Ethiopia’s Tigray Region. Geneva: USAID, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amnesty International . Ethiopia: troops and militia rape, abduct women and girls in Tigray conflict – new report Nairobi, Kenya, 2012. Available: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2021/08/ethiopia-troops-and-militia-rape-abduct-women-and-girls-in-tigray-conflict-new-report/ [Accessed 08 Oct 2021]. 10.1186/1472-6963-12-352 [DOI]

- 25.Jerving S. Ethiopia suspends MSF and NRC over ‘dangerous’ accusations, 2021. Available: https://www.devex.com/news/ethiopia-suspends-msf-and-nrc-over-dangerous-accusations-100541 [Accessed 10 Sep 2021]. 10.1371/journal.pone.0131195 [DOI]

- 26.Medhanyie A, Spigt M, Kifle Y, et al. The role of health extension workers in improving utilization of maternal health services in rural areas in Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:352. 10.1186/1472-6963-12-352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gebrehiwot TG, San Sebastian M, Edin K, et al. The health extension program and its association with change in utilization of selected maternal health services in Tigray region, Ethiopia: a segmented linear regression analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0131195–e95. 10.1371/journal.pone.0131195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsolekile LP, Puoane T, Schneider H, et al. The roles of community health workers in management of non-communicable diseases in an urban township. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med 2014;6:E1–8. 10.4102/phcfm.v6i1.693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eshaq AM, Fothan AM, Jensen EC, et al. Malnutrition in Yemen: an invisible crisis. Lancet 2017;389:31–2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32592-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martorell R. The nature of child malnutrition and its long-term implications. Food Nutr Bull 1999;20:288–92. 10.1177/156482659902000304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woldehanna T, Behrman JR, Araya MW. The effect of early childhood stunting on children's cognitive achievements: evidence from young lives Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev 2017;31:75–84. 10.1007/s00213-011-2550-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cousins S. Syrian crisis: health experts say more can be done. Lancet 2015;385:931–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60515-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.The Lancet . Yemen and cholera: a modern humanity test. Lancet 2017;390:626. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32210-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tesfay FH, Gesesew HA. How conflict has made COVID-19 a neglected epidemic in Ethiopia Kenya: the conversation, 2021. Available: https://theconversation.com/how-conflict-has-made-covid-19-a-neglected-epidemic-in-ethiopia-167499 [Accessed 14 Oct 2021]. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31353-3 [DOI]

- 35.Checchi F, Warsame A, Treacy-Wong V, et al. Public health information in crisis-affected populations: a review of methods and their use for advocacy and action. Lancet 2017;390:2297–313. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30702-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Samarasekera U, Horton R. Improving evidence for health in humanitarian crises. Lancet 2017;390:2223–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31353-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Checchi F, Roberts L. Documenting mortality in crises: what keeps us from doing better. PLoS Med 2008;5:e146. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jerving S. WHO chief calls Ethiopia's Tigray conflict 'very horrific': DEVEX, 2021. Available: https://www.devex.com/news/who-chief-calls-ethiopia-s-tigray-conflict-very-horrific-99927 [Accessed 20 May 2021].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.