Abstract

Adaptation of cellular function with the nutrient environment is essential for survival. Failure to adapt can lead to cell death and/or disease. Indeed, energy metabolism alterations are a major contributing factor for many pathologies, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes. In particular, a primary characteristic of cancer cells is altered metabolism that promotes survival and proliferation even in the presence of limited nutrients. Interestingly, recent studies demonstrate that metabolic pathways produce intermediary metabolites that directly influence epigenetic modifications in the genome. Emerging evidence demonstrates that metabolic processes in cancer cells fuel malignant growth, in part, through epigenetic regulation of gene expression programs important for proliferation and adaptive survival. In this review, recent progress towards understanding the relationship of cancer cell metabolism, epigenetic modification, and transcriptional regulation will be discussed.

Specifically, the need for adaptive cell metabolism and its modulation in cancer cells will be introduced. Current knowledge on the emerging field of metabolite production and epigenetic modification will also be reviewed. Alterations of DNA (de)methylation, histone modifications, such as (de)methylation and (de)acylation, as well as chromatin remodeling, will be discussed in the context of cancer cell metabolism. Finally, how these epigenetic alterations contribute to cancer cell phenotypes will summarized. Collectively, these studies reveal that both metabolic and epigenetic pathways in cancer cells are closely linked, representing multiple opportunities to therapeutically target the unique features of malignant growth.

Keywords: cancer, metabolism, glycolysis, oxidative phosphorylation, histone, acetylation, methylation, acylation, DNA methylation

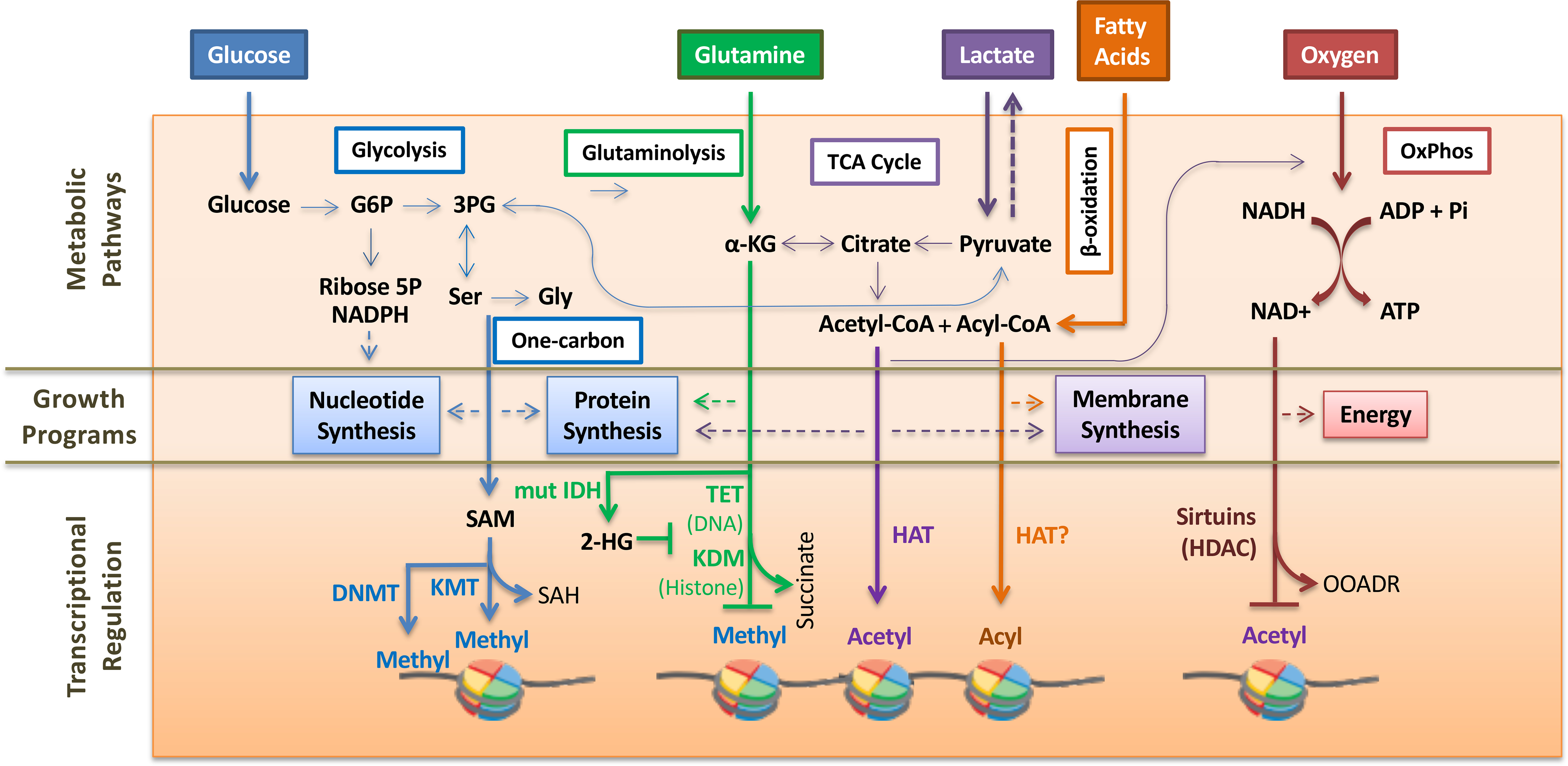

Graphical Abstract

Cancer cell metabolism fuels malignant growth, in part, through epigenetic regulation of gene expression programs important for proliferation and adaptive survival. Specifically, extracellular metabolites feed metabolic pathways that promote cancer cell growth. These metabolic pathways also produce intermediary metabolites required for histone modifications, which in turn regulates transcription of genes in cell growth pathways.

The coordination of metabolic function with the environment

The interdependence of nutrient availability, cell growth and division have long been recognized [1–3]. Growth (i.e. the production of cellular building blocks, or biomass) is required for creation of a new cell during division and is directly connected to metabolic pathways, such as glycolysis, the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation [4] (Fig. 1). For example, yeast mutants originally identified as having defects in cell growth and division were later found to have metabolic deficiencies. Indeed, an abundance of Cell Division Cycle (CDC) genes are involved in energy metabolic and biosynthetic pathways [4]. For example, Cdc53 is a cullin and structural component of SCF complex involved in the G1-S transition, as well as a regulator of methionine biosynthesis genes that contribute to nucleotide and protein synthesis [5].

Figure 1. Epigenetic modifications linked to cancer cell metabolism.

Cancer cells have increased consumption of glucose for aerobic glycolysis that supports nucleotide and protein synthesis. G6P, glucose-6-phosphate. 3-PG, 3-phosphoglycerate. Ser and Gly is serine and glycine, respectively. One carbon metabolism produces s-adenosyl-methionine (SAM), a required cofactor for DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) and lysine methyltransferase (KMT). The methyltransferase reaction produces S-adenosyl-homocysteine (SAH). Glutamine metabolism supports lipid biosynthesis via the TCA cycle. α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) produced during glutaminolysis is a required cofactor for DNA demethylase TET enzymes and lysine demethylases (KDM). A byproduct of the demethylase reaction is succinate. Mutant isocitrate dehydrogenase (mut IDH) converts α-ketoglutarate to 2-hydroxyglutarate (2-HG), which inhibits demethylase reactions. Acetyl-CoA produced in the TCA cycle and β-oxidation is used by histone acetyltransferases (HAT). Fatty acid β-oxidation is important for membrane synthesis and also produces acyl-CoA that can be used by HATs for additional histone acylation reactions. Neoplastic cells also exhibit oxidative phosphorylation (OxPhos) to produce energy. Class III histone deacetylation (HDAC) reactions by sirtuins require NAD+ produced during oxidative phosphorylation. The deacetylation reaction produces O-acetyl ADP-ribose (OAADR) as a byproduct.

In changing nutrient-rich or -limiting environments, cells have the remarkable ability to sense these dynamic environments and reprogram their energy metabolism and/or proliferative capacity accordingly. Indeed, dynamic nutrient environments are ubiquitous throughout nature and include competitive growth environments of proliferating microorganisms and tissue niches in multicellular organisms. Prime examples of metabolic plasticity can be found in biological systems that display oscillations in environmental nutrients and intracellular metabolism. For example, in metabolically-synchronized S. cerevisiae, homeostasis is observed through elegant organization of energy availability and cellular programs related to growth and division [4,6,7], called the Yeast Metabolic Cycle. Corresponding temporal oscillations in metabolite abundance were also observed as early as the 1960s [8–10]. Such organization entails temporal separation of metabolic processes, such that biogenesis (production of building blocks for a new cell) occurs before cell division. Importantly, this metabolic coordination allows cells to quickly organize and adapt their metabolic output and proliferation in synchrony with changing environmental conditions.

These Yeast Metabolic Cycles are not unlike circulating glucose and insulin oscillations observed in the sleep-wake cycles of circadian rhythms in mammals. Indeed, pancreatic β cells exhibit exquisitely synchronized fluctuations of glucose metabolism, ATP production, calcium signaling, and insulin secretion [11]. In addition, oscillations in mitochondrial respiration and glycolysis have been observed in the heart, liver, and neurons [12]. Collectively, these observations demonstrate the importance of metabolic plasticity in coordination with the nutrient environment in order to optimize cellular survival, fitness and growth programs.

Metabolic reprogramming in cancer cells

Cancer cells exhibit profound metabolic plasticity in order to survive and proliferate in diverse microenvironments in vivo, including expansion of the primary tumor, dissemination and migration into new tissue with differing nutrient availability, and growth of secondary tumors requiring high metabolic demands for proliferation [13,14].

The metabolism of cancer cells differs dramatically from that of normal cells in several ways. First observed by Otto Warburg in 1924, many cancer cells metabolize glucose via aerobic glycolysis, rather than oxidative phosphorylation, thus prioritizing biosynthesis over energy production. Later studies expanded these observations and determined that elevated rates of glucose and glutamine consumption, lipid biosynthesis, pentose phosphate metabolism, autophagy and redox maintenance are all characteristics of rapidly proliferating cancer cells [13] (Fig. 1). The metabolic signature of cancer cells is so distinguishable from that of normal cells that current clinical use of positron emission tomography (PET) measuring regional glucose metabolism has a greater than 90% accuracy in the detection of epithelial metastases [15].

Although many of the advantages of cancer cell metabolism in vivo are still being determined, there are several selective pressures that may explain the evolution of these distinct metabolic signatures [16]. For example, increased use of glycolytic pathways decreases the dependence on highly aerobic conditions that may not be available prior to stimulation of angiogenesis in surrounding tissue. Furthermore, intermediates of the glycolytic pathway can also be used for anabolic reactions, such as pyruvate for alanine and malate synthesis.

Importantly, cancer cells must cohabitate with non-cancerous surrounding tissue, thus a symbiotic relationship develops that supports maintenance of normal and growth of cancer cells. For example, cancer cells produce lactate as an end product of aerobic glycolysis. Lactate may be transported into neighboring stromal cells to regenerate and secrete pyruvate, thus refueling cancer cell metabolism [17]. In addition, ‘Reverse Warburg Effect’ has been observed and is consistent with high glycolytic activity in stromal cells that produce by-products to feed cancer cell metabolism [18]. This type of cell-to-cell metabolic cooperation is reminiscent of ‘quorum-sensing’, which enacts coherent cellular changes in response to population density. Quorum-sensing mechanisms have been observed in pathogenic and microorganisms, and have also been proposed to assist cancer cells during metastatic colonization in different tissues [19,20]. Indeed, because tumor microenvironments are extremely cell dense with signaling among cancer cells and between cancer and stromal cells, cooperative behavior that enhances metabolic function and fitness is likely to occur. These types of cooperative behaviors are particularly important given the fluctuations in nutrient availability in circulating blood.

Cancer cells can achieve this metabolic reprogramming through multiple genetic alterations. For example, oncogenic mutations in RAS and BRAF, which are commonly found in melanoma and cancers of the pancreas, lung, colon and rectum, result in increased glucose uptake even in the presence of limiting nutrients [21,22]. In addition, the Myc oncogene, which is overexpressed in many cancers, regulates a transcriptional program associated with increased glucose and glutamine consumption in cancer cells [23]. Indeed, cancers that depend on Myc overexpression for survival often exhibit ‘oncogene addiction’ [24], the dependency on a single activated oncogenic protein or pathway to maintain their malignant properties [25], the origins of which may have roots in addiction to glutamine.

Epigenetic regulation facilitates metabolic reprogramming in cancer cells

Adaptive cellular responses, including metabolic adaptation, are often achieved by inducible changes in gene expression programs [26]. An ideal mechanism to achieve this is through epigenetic modification, which is rapid and reversible, and can occur through numerous enzymes, such as DNA and histone (de)methylases and (de)acetylases.

Indeed, changes in chromatin architecture are known to regulate inducible gene expression in response to intra- and extracellular signals. For example, temporal metabolic oscillations in the Yeast Metabolic Cycle are largely attributed to dynamic chromatin changes that influence the expression of metabolic genes. For example, bursts of mitochondrial respiration produce elevated intracellular acetyl-CoA levels generated by the TCA cycle [27]. A corresponding increase in acetyl-CoA-dependent histone acetylation and increased expression of genes related to cell growth and division is also observed during respiration [28,29].

This connection between metabolic pathways and histone modifications is not limited the Yeast Metabolic Cycle. Interestingly, in mammalian systems, required cofactors for several epigenetic modifications are intermediary metabolites produced during metabolic pathways, such as glycolysis and the TCA cycle (Fig. 1). Moreover, periodic histone acetylation, methylation, and chromatin-remodeling coincides with changes in expression of circadian and metabolic genes at specific times of the circadian clock in mammals [30,31]. For example, different studies demonstrate that 3–20% of genes from different mouse tissues exhibit periodic expression in tune with circadian rhythms [32]. In mouse livers, histone acetylation across the genome, and particularly on genes that regulate circadian cycles and metabolism of glucose and lipids, promotes gene expression [31,33–36]. NAD+-dependent deacetylation of circadian gene loci also exhibits periodic rhythms and helps to create a tightly-regulated circadian transcriptional program [37]. Importantly, the core circadian transcription factor, CLOCK, is an acetyltransferase itself [38], illustrating the interdependent nature of circadian metabolism, histone modification, and transcriptional regulation.

Clearly, epigenetic regulation of metabolic processes is an ideal mechanism to elicit rapid adaptive changes in gene expression, which would provide survival and proliferative advantages for cancer cells. In the subsequent sections, several metabolic pathways and their related epigenetic modifications will be discussed in relation to cancer cell metabolism.

One-carbon metabolism promotes DNA and histone methylation

One-carbon metabolism includes the folate and methionine cycles that generate one-carbon units (i.e. methyl groups). These methyl groups are donated to methionine recycling pathway, thymidylate synthesis, and purine synthesis needed for the production of new nucleotides during DNA replication (Fig 1).

The significance of one-carbon metabolism for malignant growth was identified over 60 years ago by Sydney Farber, MD, who found that disruption of the folate cycle with a folic acid antagonist resulted in temporary remission in children with acute leukemia [39]. During one-carbon metabolism, serine donates its side chain to tetrahydrofolate to drive the folate cycle, which in turn recycles methionine from homocysteine. Inhibition of serine synthesis, a major source of one-carbon units, has also been found to disrupt cancer progression [40]. Cancer cells can potentiate one-carbon metabolism through overexpression of metabolic enzymes, such as of 3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PGDH), which redirects glycolysis intermediates to the serine synthesis pathway [41].

Serine and ribose-5-phosphate can also be used for de novo purine synthesis in cancer cells [42]. The resulting ATP and methionine contributed by serine catabolism can then be used by methionine adenosyl-transferase to generate S-adenosyl-methionine (SAM) [43], the required cofactor for cellular methylation reactions, including DNA and histone methylation [44]. A by-product of this methylation reaction is S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH), a potent inhibitor of methyltransferases [45]. In order to prevent its accumulation, SAH is hydrolyzed to homocysteine and adenine by S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase (AHCY) [43]. Subsequently, homocysteine can be remethylated to methionine in the folate cycle [40]. Interestingly, dietary consumption of methionine directly influences SAM/SAH ratios, resulting in corresponding changes in methylation patterns and gene expression [46].

DNA methylation, in particular, is one of the most abundant and well-studied epigenetic modification, occurring in approximately 70% of CpG di-nucleotides in the mammalian genome. Virtually all types of cancers have reported alterations in DNA methylation [47]. DNA hypomethylation, and gene expression activation, has been observed at repetitive elements and oncogenes, whereas DNA hypermethylation, and repression, is observed at tumor suppressor loci [48].

Conversely, histone methylation predominately regulates gene expression by recruiting transcriptional activators or repressors to genic loci. While the histone (de)methylases are termed ‘writers’, factors that bind these modifications are collectively termed ‘readers’. Several writers and readers have gain-of-function or loss-of-function mutations in cancer cells. For example, the enhancer of zeste homologue 2 (EZH2) methyltransferase is both mutated and overexpressed in many cancers, leading to aberrant abundance of its methylated product H3 lysine 27 (H3K27) [49]. Methylated H3K27 is important for the temporal regulation of developmental gene expression. Increased and altered localization of H3K27 methylation can result in repression of lineage-specific genes, resulting in a stem cell-like transcriptional program that supports carcinogenesis.

α-ketoglutarate is required for DNA and histone demethylation

As mentioned, cancer cells also have increased consumption of glutamine, which can contribute to different growth promoting pathways, such as amino acid synthesis, nucleotide synthesis, and TCA cycle-related biosynthesis. The first step of glutamine catabolism is its conversion to glutamate, which can promote proliferation through protein synthesis, incorporation in redox pathways, and conversion to α-ketoglutarate for replenishing TCA intermediates [50] (Fig 1).

α-ketoglutarate is also a required cofactor for Jumonji C (JmjC)-containing histone demethylases, which are 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases. This demethylase reaction also requires oxygen and Fe(II) and is specific to removal of methyl groups from tri-methylated histones, creating succinate as a byproduct [51].

Another epigenetic modifier that is a 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases, is the Ten-Eleven Translocation (TET) DNA demethylases. TET was originally named after a translocation between chromosomes 10 and 11, creating a fusion with the Mixed Lineage Leukemia (MLL) gene [52]. Although TET proteins were discovered quite some time ago, their function as DNA demethylases was only recently discovered to be iterative oxidation of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to 5-hydroxymethyl cytosine (5hmC), then 5-formylcytosine (5fC), then 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC), by TET1–3 respectively [53–55].

The cellular abundance of these oxidized variants are much lower than that of 5mC [55], with variation in different organisms, tissues, and during development and differentiation [56]. Some technical challenges exist in discriminating 5mC from its oxidized variants in genome mapping experiments [57]. Nevertheless, initial studies reveal that 5hmC is abundant in genic regions, including promoters and exons [58]. Cancers cells exhibit both increases and decreases of 5hmC, however current trends indicate that decreases are more common, particularly in melanoma and colon cancer.

Alteration of the α-ketoglutarate metabolism pathway is also altered cancers. Specifically, mutations in isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 and 2 (IDH1 and 2), which converts isocitrate to α-ketoglutarate during glutamine metabolism, has been observed in human brain cancers and other hematological malignancies [59,60]. These mutations result in the ability of IDH1 and 2 to convert α-ketoglutarate to the oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate, which inhibits DNA and histone demethylase reactions through depletion of the cofactor α-ketoglutarate, and enzymatic inhibition of demethylase activity by the oncometabolite [61] (Fig. 1). Inhibition of mutant IDH activity results in decreased cell proliferation and increased differentiation in glioma cells [61].

Acetyl Co-A is a central growth metabolite and feeds histone acetylation

As previously mentioned, the TCA cycle provides essential intermediary metabolites for nitrogen utilization in building amino acids and nitrogenous bases in nucleic acids. Also, pyruvate derived acetyl-CoA in the TCA cycle is required for biosynthesis of fatty acids, sterols and amino acids. Moreover, acetyl-CoA is also a required cofactor for histone acetylation, an abundant histone modification [62] (Fig. 1).

Recent studies demonstrate that enzymes involved in acetyl-CoA metabolism can translocate to the nucleus to supply nuclear acetyl-CoA pools [63]. This is contradictory to the long-standing assumption that restricts the location of these enzymes to the mitochondria and/or cytoplasm. Histone acetylation levels appear to be coordinated with cellular abundance of acetyl-CoA, as exogenous supplementation of acetate increases histone acetylation. Furthermore, metabolic enzymes, such as ATP-citrate lyase (ACLY) protein, which converts citrate to acetyl-CoA, and acetyl-CoA synthetase (ACCS2) are often overexpressed in cancer cells concomitant with elevated histone acetylation [64–66]. Reduction of these metabolic enzymes markedly decreases histone acetylation and tumor growth [64,65].

Histone acetyltransferases use nuclear acetyl-CoA during high glucose conditions to acetylate histones, creating a permissive state for transcription [67]. Histone acetylation also promotes the expression of genes involved in the TCA cycle [4], thereby creating a feedback mechanism that supports the acetyl-CoA production pathway. Furthermore, histone acetylation regulates the expression of genes involved in cell growth and proliferation, namely ribosome biogenesis, translation, amino acid metabolism, further demonstrating the link between high nutrient environments and promotion of cell proliferation.

Oncogene activation can also promote histone acetylation and subsequent transcriptional growth programs. For example, constitutive expression of oncogenic KRAS (G12D) activates the AKT kinase, which increases glycolytic-production of citrate, as well as ACLY phosphorylation and activation [68]. The result is global increase of histone acetylation in cancer cells expressing oncogenic KRAS.

As previously mentioned, the Myc oncogene regulates glutamine metabolism and biogenesis pathways through altered metabolic gene expression [23,69]. The oncogenic potential of Myc is closely linked to its associated chromatin-modifying abilities. When overexpressed, Myc binds ubiquitously throughout the genome at both canonical Myc binding sites (E box motifs) and intergenic regions, regulating nearly 15% of all genes [70–72]. A mechanism of Myc-induced transcriptional activation involves the recruitment of a coactivator complex that contains the GCN5 histone acetyltransferase [73], which requires acetyl-CoA. This coactivator complex is critical to the function of Myc as a transcription factor and oncogene, as siRNA-mediated GCN5 knockdown blocks Myc-induced histone acetylation and activation of target genes [74]. Myc overexpression also leads to increased production of mitochondrial acetyl-CoA [75], thereby establishing a feed-forward pathway for production and use of acetyl-CoA.

Fatty acid oxidation and histone acylation

It is widely known that fatty acids are used by proliferating cancer cells to promote membrane synthesis. Fatty acid oxidation is also another pathway to produce acetyl-CoA during low glucose conditions. By products of β-oxidation include acetyl-CoA and other acyl-CoAs depending on the carbon chain length of the fatty acid substrate. These acyl-CoA include propionyl-, malonyl-, crotonyl-, butyryl-, succinyl-, glutaryl, 2-hydroxy-isobutyryl-, and β-hydroxy-butyryl-CoA. Interestingly, expression of fatty acid metabolism genes and corresponding histone modifications have also been observed in cultured cells, indicating that, much like histone acetylation, other histone acylation levels are closely linked to the abundance of required cofactors [76,77]. Indeed, known acetyltransferases have been identified to facilitate the histone acylation [78], again suggesting common modes of regulation between acetylation and other acylations.

In cultured cells with ample abundance of glucose and glutamine, these acylations were found to be in low abundance compared to acetyl-CoA [79]. Furthermore, the functions of many acylations are still under investigation. However, initial studies suggest that histone crotonylation, in particular, play roles in transcriptional activation based on in vitro experiments where crotonate was exogenously added to culture media of mammalian cells [80,81]. Furthermore, in the Yeast Metabolic Cycle that spontaneously undergoes distinct periodic expression of metabolic enzymes associated with the TCA cycle and fatty acid oxidation pathway, a transcriptionally repressive role for histone crotonylation was identified [77]. Specifically, histone crotonylation and acetylation were temporally segregated in relation to the gene activation and repression. During oxidative phosphorylation and acetyl-CoA production, histone acetylation and gene activation at ‘growth gene’ loci was observed. However, during fatty acid oxidation, histone crotonylation increases at these same loci, concomitant with decreased expression. Exogenous addition of crotonic acid also reduces expression of ‘pro-growth’ genes. Collectively, these results suggest that histone acylations may have diverse roles in different cellular and organismal contexts.

Clearly, additional research is needed to clarify the roles of histone acylations in transcriptional regulation and their impact in cancer cells. However, initial studies demonstrate that disruptions in fatty acid metabolism from dietary lipid uptake have been linked to cancer progression [82]. Indeed, because histone acylations are extremely responsive to cellular metabolic status, it is likely that they play important roles in cancer cells that need to rapidly adapt to changing nutrient conditions. For example, initial studies demonstrate that histone crotonylation is decreased in hepatocellular carcinoma, and increasing crotonylation inhibits cell motility and proliferation [83].

Oxidative phosphorylation and histone deacetylation

Oxidative phosphorylation produces energy in the form of ATP for numerous cellular processes important for proliferating cancer cells. In the process NADH is converted to NAD+, which are required cofactors for class III histone deacylases, namely sirtuins [84,85] (Fig. 1).

Sirtuins (SIRT) are implicated in aging, diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular disease, inflammatory disease, and neurodegenerative disease, the origins of which have many links to metabolic dysfunction [86]. An initial connection to cancer cell metabolism was identified when SIRT1 was found to deacetylate and repress the activity of the tumor suppressor TP53 [87,88]. These results suggest an oncogenic function for SIRT1, however, because of its diverse roles in different cellular processes, sirtuins have also been associated with tumor suppressor function [89]. Specifically, SIRT2, 3 and 4 can maintain genome integrity through regulation of the cell cycle and/or mitochondrial metabolism [90–92]. SIRT6 or SIRT4 deletion has been observed in several cancers and leads to increased expression of glycolytic and glutamine metabolism genes concomitant with tumor growth in mice [92,93].

Given the important role of histone acylation in regulating growth transcriptional programs, deacylases are expected similarly be regulated by cancer cell metabolism and control proliferative capacity.

Chromatin remodelers promote cancer cell metabolism

Not only are histone modifications directly linked to energy metabolism, but chromatin remodelers are as well. Chromatin remodelers use the energy of ATP to alter the contacts between histones and the DNA to reposition or edit nucleosome composition [94]. Chromatin remodelers have diverse roles in many DNA-templated processes, such as transcription, DNA repair, and replication [95,96]. The first characterized ATP-dependent remodeling complex was the S. cerevisiae SWI/SNF (switch/sucrose non-fermenting) complex [97,98], the subunits of which were originally identified as transcriptional regulators of metabolic pathways fueled by alternative fermentable carbon sources [99,100].

The SWI/SNF complex is highly conserved and regulates energy metabolism in both yeast and mammals. Mammalian SWI/SNF complexes are a family of BRG-/BRM-associated factor (BAF) and Polybromo-associated BAF (PBAF) complexes. The link between BAF/PBAF and mammalian disease has been repeatedly demonstrated, as loss of function contributes to developmental disorders and cancer [101–103].

Intriguing similarities exist between the metabolism of cancer cells and S.cerevisiae, in that both are optimized for rapid proliferation in diverse nutrient environments. S. cerevisiae have also evolved metabolic diversity in carbon catabolism pathways. Specifically, in glucose-rich environments, budding yeast preferentially utilize glycolysis followed by fermentation. When glucose is limiting, cells shift their energy metabolism to respiration [104]. Growth in high glucose results in “glucose repression,” which is characterized by transcriptional repression of genes involved in alternate carbon source metabolism, including those in respiration [105]. The state of “glucose repression” is not unlike that of the “Warburg effect”, where cancer cells utilize aerobic glycolysis to feed growth pathways, such as lipid and protein biogenesis, over energy production via respiration [106].

One type of cancer that is clearly dependent on the Warburg effect is clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), named after its cellular histological appearance caused by elevated glycogen and lipid storage resulting from increased glycolysis. Approximately, 46% of ccRCCs have mutations in Polybromo-1 (PBRM1) [107], a subunit of the PBAF chromatin-remodeling complex. It is the second most mutated gene after the Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor gene, which is mutated in 48% of ccRCCs. A mouse model of ccRCC caused by inactivation of both PBRM1 and VHL recapitulated the histological features of patient-derived ccRCCs [108]. Importantly, increased glycogen storage and decreased expression of genes in the oxidative phosphorylation pathway are dependent on loss of PBRM1 and VHL [109], demonstrating that BAF/PBAF complexes plays a critical role in the regulation of cancer cell metabolism.

BAF/PBAF are not the only chromatin remodelers known to regulate energy metabolism. The INO80 complex, originally identified for its role in inositol metabolism [110,111], also regulates glycolytic and respiration pathways in budding yeast [112]. Similar to the SWI/SNF complex, the INO80 complex regulates “glucose repression” in yeast. In glucose-rich environments, mutants of the INO80 complex display increased expression of nearly every gene involved in the respiration pathway, while genes in glycolysis are decreased [112]. Accordingly, mitochondrial potential and oxygen consumption are increased in INO80 mutants.

Subunits of the INO80 complex exhibit multiple alterations in a variety of cancers, with notable amplification of the ACTL6A subunit in lung squamous cell carcinomas [107]. Additional studies demonstrate that overexpression of the INO80 subunits are needed to maintain proliferation and anchorage-independent growth of lung cancer cells [113]. Expression analysis also reveal that several INO80 subunits exhibit increased expression in metastatic melanoma compared to primary melanoma and benign nevi [114]. Silencing of INO80 subunit expression impairs melanoma cell growth in culture and in mouse xenografts. Furthermore, in a mouse model for colon cancer, Ino80 haplo-insufficiency decreases tumor formation and increases survival [115]. Taken together, these results suggest that, unlike the BAF/PBAF remodeler, the INO80 complex has oncogenic roles during carcinogenesis.

The roles of INO80 in cancer development may be multi-faceted. For example, alterations in cancer gene expression are observed in cells with increased INO80 subunit expression [113,114]. DNA damage checkpoint activation has also been observed in Ino80 haplo-insufficient cells [115]. However, yeast studies hint that INO80 function may also be related to metabolic reprogramming. As mentioned, loss of INO80 results in decreased glycolytic metabolism [112]. In addition, INO80 deficiency results in uncontrolled proliferation in low nutrient (i.e. metabolically unfavorable) environments [116]. Interestingly, yeast genetic screens identify novel connections between INO80 and the Target of Rapamycin (TOR) signaling pathway [117], which is responsible for coordinating stress and growth responses with environmental cues in both yeast and mammals. The mammalian TOR (mTOR) kinase is deregulated in numerous metabolic disorders and cancers [118]. Recent research reveals that INO80 regulates TOR-dependent transcriptional pathways [116], and suggests that INO80 promotes histone acetylation on growth genes downstream of TOR signaling [117].

Future Directions

The intersection of epigenetics and metabolism has just emerged in the last decade. Thus, knowledge of how these processes are co-opted to fuel cancer evolution has only begun to be collected. Nevertheless, growing evidence demonstrates that the specialized metabolism of cancer cells elicits corresponding changes in the epigenome to promote growth and survival transcriptional programs. Future research may be focused on imposing controlled metabolic fluctuations in mammalian cells and unbiased profiling of corresponding histone marks and gene expression changes. In addition, how chromatin remodelers may be influenced by dynamic changes in metabolism and corresponding histone modifications has yet to be investigated. These studies are critical to understanding the influence of chromatin remodelers in disease and may reveal novel epigenetic therapies to combat carcinogenesis.

Because cancer cells depend on metabolic reprogramming for survival, targeting of cancer cell metabolism has proven successful to limit tumor growth in mouse studies [13,119]. For example, PIK3CA mutant-derived lung adenocarcinomas in mice respond to combinatorial therapies that inhibit both PI3K activity and mTOR, a central regulator of cellular response to environmental nutrients and stress [120]. Also, inhibition of lactate dehydrogenase A in mouse models of non-small cell lung cancer alters pyruvate metabolism in cancer cells and inhibits tumorigenesis [121]. Inhibition of acetyl Co-A catabolism in energy metabolism pathways also reduces tumor burden in mouse models [64]. As siRNA and CRISPR technologies have increased abilities for genetic screens in mammalian cells, several metabolic pathways, including glucose and serine metabolism, have been found to be essential for survival and proliferation of a number of cancer cells [122–124].

As many therapies have already been developed to treat other metabolic disorders, such as heart disease and diabetes, opportunities exist to repurpose them for cancer therapy. Indeed, several have proven effective in limiting growth and proliferation of cancer cells, particularly in combination with other chemotherapies [119], and are currently being tested in clinical trials [125]. The influence of these metabolic therapeutics on epigenetic modifications and transcriptional growth programs are largely unknown, yet studies are growing in number. Likewise, thorough examinations of metabolic alteration in response to epigenetic therapies is lacking. Future research will be needed to resolve these questions and many other in order to expand our understanding of the links between cancer cell metabolism and epigenetic modification.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grant R35GM119580 to AJM.

Abbreviations:

- TCA

tricarboxylic acid

- acetyl-CoA

acetyl coenzyme A

- NAD

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- SAM

s-adenosyl-methionine

- SAH

s-adenosylhomocysteine

- TET

Ten-Eleven Translocation

- 5mC

5-methylcytosine

- IDH

isocitrate dehydrogenase

- BAF

BRG-/BRM-associated factor

- PBAF

Polybromo-associated BAF

- TOR

Target of Rapamycin

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None

References

- 1.JOHNSTON G, PRINGLE J & HARTWELL L (1977) Coordination of growth with cell division in the yeast. Exp Cell Res 105, 79–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jorgensen P & Tyers M (2004) How Cells Coordinate Growth and Division. Current Biology 14, R1014–R1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jorgensen P, Nishikawa JL, Breitkreutz B-J & Tyers M (2002) Systematic identification of pathways that couple cell growth and division in yeast. Science 297, 395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cai L & Tu BP (2012) Driving the Cell Cycle Through Metabolism. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 28, 59–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patton EE, Willems AR, Sa D, Kuras L, Thomas D, Craig KL & Tyers M (1998) Cdc53 is a scaffold protein for multiple Cdc34/Skp1/F-box proteincomplexes that regulate cell division and methionine biosynthesis in yeast. Genes Dev 12, 692–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tu BP, Kudlicki A, Rowicka M & McKnight SL (2005) Logic of the Yeast Metabolic Cycle: Temporal Compartmentalization of Cellular Processes. Science 310, 1152–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klevecz RR, Bolen J, Forrest G & Murray DB (2004) A genomewide oscillation in transcription gates DNA replication and cell cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101, 1200–1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghosh A & Chance B (1964) Oscillations of glycolytic intermediates in yeast cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 16, 174–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chance B, Schoener B & Elsaesser S (1964) Control of the Waveform of Oscillations of the Reduced Pyridine Nucleotide Level in a Cell-Free Extract. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 52, 337–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chance B, Estabrook RW & Ghosh A (1964) Damped Sinusodial Oscillations of Cytoplasmic Reduced Pyridine Nucleotide in Yeast Cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 51, 1244–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacDonald PE & Rorsman P (2006) Oscillations, Intercellular Coupling, and Insulin Secretion in Pancreatic β Cells. PLoS Biol 4, e49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iotti S, Borsari M & Bendahan D (2010) Oscillations in energy metabolism. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics 1797, 1353–1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Vander Heiden MG & Kroemer G (2013) Metabolic targets for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov 12, 829–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cairns RA, Harris IS & Mak TW (2011) Regulation of cancer cell metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer 11, 85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mankoff DA, Eary JF, Link JM, Muzi M, Rajendran JG, Spence AM & Krohn KA (2007) Tumor-specific positron emission tomography imaging in patients: [18F] fluorodeoxyglucose and beyond. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 3460–3469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kroemer G & Pouyssegur J (2008) Tumor Cell Metabolism: Cancer“s Achilles” Heel. Cancer Cell 13, 472–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koukourakis MI, Giatromanolaki A, Bougioukas G & Sivridis E (2007) Lung cancer: a comparative study of metabolism related protein expression in cancer cells and tumor associated stroma. Cancer Biol. Ther. 6, 1476–1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Migneco G, Whitaker-Menezes D, Chiavarina B, Castello-Cros R, Pavlides S, Pestell RG, Fatatis A, Flomenberg N, Tsirigos A, Howell A, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Sotgia F & Lisanti MP (2010) Glycolytic cancer associated fibroblasts promote breast cancer tumor growth, without a measurable increase in angiogenesis: Evidence for stromal-epithelial metabolic coupling. Cell Cycle 9, 2412–2422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ben-Jacob E, S, Coffey D & Levine H (2012) Bacterial survival strategies suggest rethinking cancer cooperativity. Trends in Microbiology 20, 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hickson J, Diane Yamada S, Berger J, Alverdy J, O’Keefe J, Bassler B & Rinker-Schaeffer C (2009) Societal interactions in ovarian cancer metastasis: a quorum-sensing hypothesis. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 26, 67–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yun J, Rago C, Cheong I, Pagliarini R, Angenendt P, Rajagopalan H, Schmidt K, Willson JKV, Markowitz S, Zhou S, Diaz LA, Velculescu VE, Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B & Papadopoulos N (2009) Glucose deprivation contributes to the development of KRAS pathway mutations in tumor cells. Science 325, 1555–1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ying H, Kimmelman AC, Lyssiotis CA, Hua S, Chu GC, Fletcher-Sananikone E, Locasale JW, Son J, Zhang H, Coloff JL, Yan H, Wang W, Chen S, Viale A, Zheng H, Paik J-H, Lim C, Guimaraes AR, Martin ES, Chang J, Hezel AF, Perry SR, Hu J, Gan B, Xiao Y, Asara JM, Weissleder R, Wang YA, Chin L, Cantley LC & DePinho RA (2012) Oncogenic Kras maintains pancreatic tumors through regulation of anabolic glucose metabolism. Cell 149, 656–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wise DR, DeBerardinis RJ, Mancuso A, Sayed N, Zhang X-Y, Pfeiffer HK, Nissim I, Daikhin E, Yudkoff M, McMahon SB & Thompson CB (2008) Myc regulates a transcriptional program that stimulates mitochondrial glutaminolysis and leads to glutamine addiction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105, 18782–18787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luo J, Solimini NL & Elledge SJ (2009) Principles of cancer therapy: oncogene and non-oncogene addiction. Cell 136, 823–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weinstein IB & Joe A (2008) Oncogene addiction. Cancer Res 68, 3077–80–discussion 3080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.López-Maury L, Marguerat S & Bähler J (2008) Tuning gene expression to changing environments: from rapid responses to evolutionary adaptation. Nat Rev Genet 9, 583–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tu BP, Mohler RE, Liu JC, Dombek KM, Young ET, Synovec RE & McKnight SL (2007) Cyclic changes in metabolic state during the life of a yeast cell. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104, 16886–16891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cai L, Sutter BM, Li B & Tu BP (2011) Acetyl-CoA induces cell growth and proliferation by promoting the acetylation of histones at growth genes. Mol Cell 42, 426–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuang Z, Cai L, Zhang X, Ji H, Tu BP & Boeke JD (2014) High-temporal-resolution view of transcription and chromatin states across distinct metabolic states in budding yeast. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 21, 854–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rutter J, Reick M & McKnight SL (2002) Metabolism and the control of circadian rhythms. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71, 307–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feng D & Lazar MA (2012) Clocks, Metabolism, and the Epigenome. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 47, 158–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Green CB, Takahashi JS & Bass J (2008) The meter of metabolism. Cell 134, 728–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akhtar RA, Reddy AB, Maywood ES, Clayton JD, King VM, Smith AG, Gant TW, Hastings MH & Kyriacou CP (2002) Circadian cycling of the mouse liver transcriptome, as revealed by cDNA microarray, is driven by the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Current Biology 12, 540–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Etchegaray J-P, Lee C, Wade PA & Reppert SM (2003) Rhythmic histone acetylation underlies transcription in the mammalian circadian clock. Nature 421, 177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naruse Y, Oh-hashi K, Iijima N, Naruse M, Yoshioka H & Tanaka M (2004) Circadian and light-induced transcription of clock gene Per1 depends on histone acetylation and deacetylation. Molecular and Cellular Biology 24, 6278–6287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feng D, Liu T, Sun Z, Bugge A, Mullican SE, Alenghat T, Liu XS & Lazar MA (2011) A circadian rhythm orchestrated by histone deacetylase 3 controls hepatic lipid metabolism. Science 331, 1315–1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Masri S & Sassone-Corsi P (2014) Sirtuins and the circadian clock: bridging chromatin and metabolism. Science Signaling 7, re6–re6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doi M, Hirayama J & Sassone-Corsi P (2006) Circadian Regulator CLOCK Is a Histone Acetyltransferase. Cell 125, 497–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.FARBER S & DIAMOND LK (1948) Temporary remissions in acute leukemia in children produced by folic acid antagonist, 4-aminopteroyl-glutamic acid. N. Engl. J. Med. 238, 787–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Serefidou M, Venkatasubramani AV & Imhof A (2019) The Impact of One Carbon Metabolism on Histone Methylation. Frontiers in Genetics 10, 919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Locasale JW, Grassian AR, Melman T, Lyssiotis CA, Mattaini KR, Bass AJ, Heffron G, Metallo CM, Muranen T, Sharfi H, Sasaki AT, Anastasiou D, Mullarky E, Vokes NI, Sasaki M, Beroukhim R, Stephanopoulos G, Ligon AH, Meyerson M, Richardson AL, Chin L, Wagner G, Asara JM, Brugge JS, Cantley LC & Vander Heiden MG (2011) Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase diverts glycolytic flux and contributes to oncogenesis. Nat Genet 43, 869–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maddocks ODK, Labuschagne CF, Adams PD & Vousden KH (2016) Serine Metabolism Supports the Methionine Cycle and DNA/RNA Methylation through De Novo ATP Synthesis in Cancer Cells. Mol Cell 61, 210–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cantoni GL (1953) S-Adenosylmethionine; a new intermediate formed enzymatically from L-methionine and adenosinetriphosphate. J Biol Chem 204, 403–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Teperino R, Schoonjans K & Auwerx J (2010) Histone Methyl Transferases and Demethylases; Can They Link Metabolism and Transcription? Cell Metabolism 12, 321–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.GIBSON KD, WILSON JD & UDENFRIEND S (1961) The enzymatic conversion of phospholipid ethanolamine to phospholipid choline in rat liver. J Biol Chem 236, 673–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mentch SJ, Mehrmohamadi M, Huang L, Liu X, Gupta D, Mattocks D, Gómez Padilla P, Ables G, Bamman MM, Thalacker-Mercer AE, Nichenametla SN & Locasale JW (2015) Histone Methylation Dynamics and Gene Regulation Occur through the Sensing of One-Carbon Metabolism. Cell Metabolism 22, 861–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Greenberg MVC & Bourc’his D (2019) The diverse roles of DNA methylation in mammalian development and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio 20, 590–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schübeler D (2015) Function and information content of DNA methylation. Nature 517, 321–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Michalak EM, Burr ML, Bannister AJ & Dawson MA (2019) The roles of DNA, RNA and histone methylation in ageing and cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio 20, 573–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cluntun AA, Lukey MJ, Cerione RA & Locasale JW (2017) Glutamine Metabolism in Cancer: Understanding the Heterogeneity. Trends in Cancer 3, 169–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tsukada Y-I, Fang J, Erdjument-Bromage H, Warren ME, Borchers CH, Tempst P & Zhang Y (2006) Histone demethylation by a family of JmjC domain-containing proteins. Nature 439, 811–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lorsbach RB, Moore J, Mathew S, Raimondi SC, Mukatira ST & Downing JR (2003) TET1, a member of a novel protein family, is fused to MLL in acute myeloid leukemia containing the t(10;11)(q22;q23). Leukemia 17, 637–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ito S, D’Alessio AC, Taranova OV, Hong K, Sowers LC & Zhang Y (2010) Role of Tet proteins in 5mC to 5hmC conversion, ES-cell self-renewal and inner cell mass specification. Nature 466, 1129–1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ito S, Shen L, Dai Q, Wu SC, Collins LB, Swenberg JA, He C & Zhang Y (2011) Tet Proteins Can Convert 5-Methylcytosine to 5-Formylcytosine and 5-Carboxylcytosine. Science 333, 1300–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tahiliani M, Koh KP, Shen Y, Pastor WA, Bandukwala H, Brudno Y, Agarwal S, Iyer LM, Liu DR, Aravind L & Rao A (2009) Conversion of 5-Methylcytosine to 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine in Mammalian DNA by MLL Partner TET1. Science (New York, N.Y.) 324, 930–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ruzov A, Tsenkina Y, Serio A, Dudnakova T, Fletcher J, Bai Y, Chebotareva T, Pells S, Hannoun Z, Sullivan G, Chandran S, Hay DC, Bradley M, Wilmut I & De Sousa P (2011) Lineage-specific distribution of high levels of genomic. Cell Res. 21, 1332–1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Skvortsova K, Zotenko E, Luu P-L, Gould CM, Nair SS, Clark SJ & Stirzaker C (2017) Comprehensive evaluation of genome-wide 5-hydroxymethylcytosine profiling approaches in human DNA. Epigenetics & Chromatin 10, 1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yu M, Hon GC, Szulwach KE, Song C-X, Zhang L, Kim A, Li X, Dai Q, Shen Y, Park B, Min J-H, Jin P, Ren B & He C (2012) Base-Resolution Analysis of 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine in the Mammalian Genome. Cell 149, 1368–1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dang L, White DW, Gross S, Bennett BD, Bittinger MA, Driggers EM, Fantin VR, Jang HG, Jin S, Keenan MC, Marks KM, Prins RM, Ward PS, Yen KE, Liau LM, Rabinowitz JD, Cantley LC, Thompson CB, Vander Heiden MG & Su SM (2009) Cancer-associated IDH1 mutations produce 2-hydroxyglutarate. Nature 462, 739–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dang L, Jin S & Su SM (2010) IDH mutations in glioma and acute myeloid leukemia. Trends in Molecular Medicine 16, 387–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rohle D, Popovici-Muller J, Palaskas N, Turcan S, Grommes C, Campos C, Tsoi J, Clark O, Oldrini B, Komisopoulou E, Kunii K, Pedraza A, Schalm S, Silverman L, Miller A, Wang F, Yang H, Chen Y, Kernytsky A, Rosenblum MK, Liu W, Biller SA, Su SM, Brennan CW, Chan TA, Graeber TG, Yen KE & Mellinghoff IK (2013) An inhibitor of mutant IDH1 delays growth and promotes differentiation of glioma cells. Science 340, 626–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brownell JE, Zhou J, Ranalli T, Kobayashi R, Edmondson DG, Roth SY & Allis CD (1996) Tetrahymena Histone Acetyltransferase A: A Homolog to Yeast Gcn5p Linking Histone Acetylation to Gene Activation. Cell 84, 843–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li X, Egervari G, Wang Y, Berger SL & Lu Z (2018) Regulation of chromatin and gene expression by metabolic enzymes and metabolites. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio 19, 563–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Comerford SA, Huang Z, Du X, Wang Y, Cai L, Witkiewicz AK, Walters H, Tantawy MN, Fu A, Manning HC, Horton JD, Hammer RE, McKnight SL & Tu BP (2014) Acetate Dependence of Tumors. Cell 159, 1591–1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wellen KE, Hatzivassiliou G, Sachdeva UM, Bui TV, Cross JR & Thompson CB (2009) ATP-Citrate Lyase Links Cellular Metabolism to Histone Acetylation. Science 324, 1076–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Migita T, Narita T, Nomura K, Miyagi E, Inazuka F, Matsuura M, Ushijima M, Mashima T, Seimiya H, Satoh Y, Okumura S, Nakagawa K & Ishikawa Y (2008) ATP Citrate Lyase: Activation and Therapeutic Implications in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Res 68, 8547–8554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shi L & Tu BP (2015) Acetyl-CoA and the regulation of metabolism: mechanisms and consequences. Curr Opin Cell Biol 33, 125–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lee JV, Carrer A, Shah S, Snyder NW, Wei S, Venneti S, Worth AJ, Yuan Z-F, Lim H-W, Liu S, Jackson E, Aiello NM, Haas NB, Rebbeck TR, Judkins A, Won K-J, Chodosh LA, Garcia BA, Stanger BZ, Feldman MD, Blair IA & Wellen KE (2014) Akt-Dependent Metabolic Reprogramming Regulates Tumor Cell Histone Acetylation. Cell Metabolism 20, 306–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gordan JD, Thompson CB & Simon MC (2007) HIF and c-Myc: sibling rivals for control of cancer cell metabolism and proliferation. Cancer Cell 12, 108–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cotterman R, Jin VX, Krig SR, Lemen JM, Wey A, Farnham PJ & Knoepfler PS (2008) N-Myc regulates a widespread euchromatic program in the human genome partially independent of its role as a classical transcription factor. Cancer Res 68, 9654–9662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lin CY, Lovén J, Rahl PB, Paranal RM, Burge CB, Bradner JE, Lee TI & Young RA (2012) Transcriptional Amplification in Tumor Cells with Elevated c-Myc. Cell 151, 56–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zeller KI, Zhao X, Lee CWH, Chiu KP, Yao F, Yustein JT, Ooi HS, Orlov YL, Shahab A, Yong HC, Fu Y, Weng Z, Kuznetsov VA, Sung W-K, Ruan Y, Dang CV & Wei C-L (2006) Global mapping of c-Myc binding sites and target gene networks in human B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103, 17834–17839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McMahon SB, Wood MA & Cole MD (2000) The essential cofactor TRRAP recruits the histone acetyltransferase hGCN5 to c-Myc. Molecular and Cellular Biology 20, 556–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Knoepfler PS, Zhang X-Y, Cheng PF, Gafken PR, McMahon SB & Eisenman RN (2006) Myc influences global chromatin structure. EMBO J 25, 2723–2734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.F M, J N, C P-O, PR G, M F, J K, M V & D H (2010) Myc-dependent mitochondrial generation of acetyl-CoA contributes to fatty acid biosynthesis and histone acetylation during cell cycle entry. Journal of Biological Chemistry 285, 36267–36274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Simithy J, Sidoli S, Yuan Z-F, Coradin M, Bhanu NV, Marchione DM, Klein BJ, Bazilevsky GA, McCullough CE, Magin RS, Kutateladze TG, Snyder NW, Marmorstein R & Garcia BA (2017) Characterization of histone acylations links chromatin modifications with metabolism. Nature Communications 8, 1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gowans GJ, Bridgers JB, Zhang J, Dronamraju R, Burnetti A, King DA, Thiengmany AV, Shinsky SA, Bhanu NV, Garcia BA, Buchler NE, Strahl BD & Morrison AJ (2019) Recognition of Histone Crotonylation by Taf14 Links Metabolic State to Gene Expression. Mol Cell 76, 909–921.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Khan A, Bridgers JB & Strahl BD (2017) Expanding the Reader Landscape of Histone Acylation. Structure 25, 571–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tan M, Luo H, Lee S, Jin F, Yang JS, Montellier E, Buchou T, Cheng Z, Rousseaux S, Rajagopal N, Lu Z, Ye Z, Zhu Q, Wysocka J, Ye Y, Khochbin S, Ren B & Zhao Y (2011) Identification of 67 histone marks and histone lysine crotonylation as a new type of histone modification. Cell 146, 1016–1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Li Y, Sabari BR, Panchenko T, Wen H, Zhao D, Guan H, Wan L, Huang H, Tang Z, Zhao Y, Roeder RG, Shi X, Allis CD & Li H (2016) Molecular Coupling of Histone Crotonylation and Active Transcription by AF9 YEATS Domain. Mol Cell 62, 181–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sabari BR, Tang Z, Huang H, Yong-Gonzalez V, Molina H, Kong HE, Dai L, Shimada M, Cross JR, Zhao Y, Roeder RG & Allis CD (2015) Intracellular Crotonyl-CoA Stimulates Transcription Through p300-Catalyzed Histone Crotonylation. Mol Cell 58, 203–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Peck B & Schulze A (2019) Lipid Metabolism at the Nexus of Diet and Tumor Microenvironment. Trends in Cancer 5, 693–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wan J, Liu H & Ming L (2019) Lysine crotonylation is involved in hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 111, 976–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Klar AJ, Fogel S & Macleod K (1979) MAR1-a Regulator of the HMa and HMalpha Loci in SACCHAROMYCES CEREVISIAE. Genetics 93, 37–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Imai S, Armstrong CM, Kaeberlein M & Guarente L (2000) Transcriptional silencing and longevity protein Sir2 is an NAD-dependent histone deacetylase. Nature 403, 795–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chalkiadaki A & Guarente L (2012) Sirtuins mediate mammalian metabolic responses to nutrient availability. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 8, 287–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.J L, AY N, S I, D C, F S, A S, L G & W G (2001) Negative control of p53 by Sir2alpha promotes cell survival under stress. Cell 107, 137–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Vaziri H, Dessain SK, Eaton EN, Imai S-I, Frye RA, Pandita TK, Guarente L & Weinberg RA (2001) hSIR2SIRT1 Functions as an NAD-Dependent p53 Deacetylase. Cell 107, 149–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chalkiadaki A & Guarente L (2015) The multifaceted functions of sirtuins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 15, 608–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kim H-S, Vassilopoulos A, Wang R-H, Lahusen T, Xiao Z, Xu X, Li C, Veenstra TD, Li B, Yu H, Ji J, Wang XW, Park S-H, Cha YI, Gius D & Deng C-X (2011) SIRT2 Maintains Genome Integrity and Suppresses Tumorigenesis through Regulating APC/C Activity. Cancer Cell 20, 487–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kim H-S, Patel K, Muldoon-Jacobs K, Bisht KS, Aykin-Burns N, Pennington JD, van der Meer R, Nguyen P, Savage J, Owens KM, Vassilopoulos A, Ozden O, Park S-H, Singh KK, Abdulkadir SA, Spitz DR, Deng C-X & Gius D (2010) SIRT3 is a Mitochondrial Localized Tumor Suppressor Required for Maintenance of Mitochondrial Integrity and Metabolism During Stress. Cancer Cell 17, 41–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jeong SM, Xiao C, Finley LWS, Lahusen T, Souza AL, Pierce K, Li Y-H, Wang X, Laurent G, German NJ, Xu X, Li C, Wang R-H, Lee J, Csibi A, Cerione R, Blenis J, Clish CB, Kimmelman A, Deng C-X & Haigis MC (2013) SIRT4 Has Tumor-Suppressive Activity and Regulates the Cellular Metabolic Response to DNA Damage by Inhibiting Mitochondrial Glutamine Metabolism. Cancer Cell 23, 450–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sebastián C, Zwaans BMM, Silberman DM, Gymrek M, Goren A, Zhong L, Ram O, Truelove J, Guimaraes AR, Toiber D, Cosentino C, Greenson JK, Mac Donald AI, McGlynn L, Maxwell F, Edwards J, Giacosa S, Guccione E, Weissleder R, Bernstein BE, Regev A, Shiels PG, Lombard DB & Mostoslavsky R (2012) THE HISTONE DEACETYLASE SIRT6 IS A NOVEL TUMOR SUPPRESSOR THAT CONTROLS CANCER METABOLISM. Cell 151, 1185–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhou CY, Johnson SL, Gamarra NI & Narlikar GJ (2016) Mechanisms of ATP-Dependent Chromatin Remodeling Motors. In Annual Review of Biophysics pp. 153–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Morrison AJ & Shen X (2009) Chromatin remodelling beyond transcription: the INO80 and SWR1 complexes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio 10, 373–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Clapier CR & Cairns BR (2009) The biology of chromatin remodeling complexes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 273–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cairns BR, Kim YJ, Sayre MH, Laurent BC & Kornberg RD (1994) A multisubunit complex containing the SWI1/ADR6, SWI2/SNF2, SWI3, SNF5, and SNF6 gene products isolated from yeast. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 91, 1950–1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Peterson CL, Dingwall A & Scott MP (1994) Five SWI/SNF gene products are components of a large multisubunit complex required for transcriptional enhancement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 91, 2905–2908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Stern M, Jensen R & Herskowitz I (1984) Five SWI genes are required for expression of the HO gene in yeast. - PubMed - NCBI. Journal of Molecular Biology 178, 853–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Neigeborn L & Carlson M (1984) Genes affecting the regulation of SUC2 gene expression by glucose repression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 108, 845–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hodges C, Kirkland JG & Crabtree GR (2016) The Many Roles of BAF (mSWI/SNF) and PBAF Complexes in Cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 6, a026930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kadoch C & Crabtree GR (2015) Mammalian SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complexes and cancer: Mechanistic insights gained from human genomics. Science Advances 1, e1500447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Alfert A, Moreno N & Kerl K (2019) The BAF complex in development and disease. Epigenetics & Chromatin 12, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Fiechter A, Fuhrmann GF & Käppeli O (1981) Regulation of glucose metabolism in growing yeast cells. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 22, 123–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gancedo JM (1998) Yeast carbon catabolite repression. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 62, 334–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Diaz-Ruiz R, Rigoulet M & Devin A (2011) The Warburg and Crabtree effects: On the origin of cancer cell energy metabolism and of yeast glucose repression. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics 1807, 568–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, Jacobsen A, Byrne CJ, Heuer ML, Larsson E, Antipin Y, Reva B, Goldberg AP, Sander C & Schultz N (2012) The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov 2, 401–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Nargund AM, Pham CG, Dong Y, Wang PI, Osmangeyoglu HU, Xie Y, Aras O, Han S, Oyama T, Takeda S, Ray CE, Dong Z, Berge M, Hakimi AA, Monette S, Lekaye CL, Koutcher JA, Leslie CS, Creighton CJ, Weinhold N, Lee W, Tickoo SK, Wang Z, Cheng EH & Hsieh JJ (2017) The SWI/SNF Protein PBRM1 Restrains VHL-Loss-Driven Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cell Reports 18, 2893–2906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Chowdhury B, Porter EG, Stewart JC, Ferreira CR, Schipma MJ & Dykhuizen EC (2016) PBRM1 Regulates the Expression of Genes Involved in Metabolism and Cell Adhesion in Renal Clear Cell Carcinoma. PLoS ONE 11, e0153718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ebbert R, Birkmann A & Schüller HJ (1999) The product of the SNF2/SWI2 paralogue INO80 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae required for efficient expression of various yeast structural genes is part of a high-molecular-weight protein complex. Mol. Microbiol. 32, 741–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Shen X, Mizuguchi G, Hamiche A & Wu C (2000) A chromatin remodelling complex involved in transcription and DNA processing. Nature 406, 541–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Yao W, King DA, Beckwith SL, Gowans GJ, Yen K, Zhou C & Morrison AJ (2016) The INO80 Complex Requires the Arp5-Ies6 Subcomplex for Chromatin Remodeling and Metabolic Regulation. Molecular and Cellular Biology 36, 979–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zhang S, Zhou B, Wang L, Li P, Bennett BD, Snyder R, Garantziotis S, Fargo DC, Cox AD, Chen L & Hu G (2017) INO80 is required for oncogenic transcription and tumor growth in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncogene 36, 1430–1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zhou B, Wang L, Zhang S, Bennett BD, He F, Zhang Y, Xiong C, Han L, Diao L, Li P, Fargo DC, Cox AD & Hu G (2016) INO80 governs superenhancer-mediated oncogenic transcription and tumor growth in melanoma. Genes Dev 30, 1440–1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lee S-A, Lee H-S, Hur S-K, Kang SW, Oh GT, Lee D & Kwon J (2017) INO80 haploinsufficiency inhibits colon cancer tumorigenesis via replication stress-induced apoptosis. Oncotarget 8, 115041–115053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Gowans GJ, Schep AN, Wong KM, King DA, Greenleaf WJ & Morrison AJ (2018) INO80 Chromatin Remodeling Coordinates Metabolic Homeostasis with Cell Division. Cell Reports 22, 611–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Beckwith SL, Schwartz EK, Garcia-Nieto PE, King DA, Gowans GJ, Wong KM, Eckley TL, Paraschuk AP, Peltan EL, Lee LR, Yao W & Morrison AJ (2018) The INO80 chromatin remodeler sustains metabolic stability by promoting TOR signaling and regulating histone acetylation. PLoS Genet 14, e1007216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Zoncu R, Efeyan A & Sabatini DM (2010) mTOR: from growth signal integration to cancer, diabetes and ageing. 12, 21–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Zhao Y, Butler EB & Tan M (2013) Targeting cellular metabolism to improve cancer therapeutics. Cell Death Dis 4, e532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Engelman JA, Chen L, Tan X, Crosby K, Guimaraes AR, Upadhyay R, Maira M, McNamara K, Perera SA, Song Y, Chirieac LR, Kaur R, Lightbown A, Simendinger J, Li T, Padera RF, García-Echeverría C, Weissleder R, Mahmood U, Cantley LC & Wong K-K (2008) Effective use of PI3K and MEK inhibitors to treat mutant Kras G12D and PIK3CA H1047R murine lung cancers. Nature Medicine 14, 1351–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Xie H, Hanai J-I, Ren J-G, Kats L, Burgess K, Bhargava P, Signoretti S, Billiard J, Duffy KJ, Grant A, Wang X, Lorkiewicz PK, Schatzman S, Bousamra M II, Lane AN, Higashi RM, Fan TWM, Pandolfi PP, Sukhatme VP & Seth P (2014) Targeting Lactate Dehydrogenase-A Inhibits Tumorigenesis and Tumor Progression in Mouse Models of Lung Cancer and Impacts Tumor-Initiating Cells. Cell Metabolism 19, 795–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Possemato R, Marks KM, Shaul YD, Pacold ME, Kim D, Birsoy K, Sethumadhavan S, Woo H-K, Jang HG, Jha AK, Chen WW, Barrett FG, Stransky N, Tsun Z-Y, Cowley GS, Barretina J, Kalaany NY, Hsu PP, Ottina K, Chan AM, Yuan B, Garraway LA, Root DE, Mino-Kenudson M, Brachtel EF, Driggers EM & Sabatini DM (2011) Functional genomics reveal that the serine synthesis pathway is essential in breast cancer. Nature 476, 346–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Birsoy K, Possemato R, Lorbeer FK, Bayraktar EC, Thiru P, Yucel B, Wang T, Chen WW, Clish CB & Sabatini DM (2014) Metabolic determinants of cancer cell sensitivity to glucose limitation and biguanides. Nature 508, 108–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Shalem O, Sanjana NE, Hartenian E, Shi X, Scott DA, Mikkelsen TS, Heckl D, Ebert BL, Root DE, Doench JG & Zhang F (2014) Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screening in human cells. Science 343, 84–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Peiris-Pagés M, Pestell RG, Sotgia F & Lisanti MP (2017) Cancer metabolism: a therapeutic perspective. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 14, 11–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]