Abstract

Objective

The COVID-19 pandemic led to unprecedented temporary federal and state regulatory flexibilities that rapidly transformed medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) treatment delivery. This study aimed to understand changes in treatment providers' care during COVID-19, provider experiences with the adaptations, and perceptions of which changes should be sustained long-term.

Methods

We conducted in-depth, semi-structured interviews with 20 New Jersey MOUD providers, purposively sampled to reflect diversity in provider setting, specialty, and other characteristics. Using a rapid analysis approach, we summarized content within interview domains and analyzed domains across participants for recurring concepts and themes.

Results

MOUD treatment practice changes taking place during the COVID-19 pandemic included a rapid shift from in-person care to telehealth, reduction in frequency of toxicology testing and psychosocial/counseling services, and modifications to prescription durations and take-home methadone supplies. Modifications to practice were positively received and reinforced a sense of autonomy for providers as well as enhancing the ability to provide patient-centered care. All respondents expressed support for making temporary regulatory flexibilities permanent, but differed in their implementation of the flexibilities and the extent to which they planned to modify their own practices long-term.

Conclusion

Findings support sustaining temporary regulatory and payment changes to MOUD practice, which may have improved treatment access and allowed for more flexible, individually tailored patient care. Few negative, unintended consequences were reported by providers, but more research is needed to evaluate the patient experience with changes to practice during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: Medication for opioid use disorder, Medication for addiction treatment, COVID-19, Telehealth, Methadone, Buprenorphine

1. Introduction

The spread of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) through the United States has required the implementation of extensive infectious disease control measures that have changed how health care is delivered to patients. Historical practices in providing opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment, reliant on frequent in-person contact, run directly counter to the COVID-19 response strategy of social distancing. The COVID-19 pandemic has stress-tested these practices and, in the process, created “natural experiments” in more-flexible provision of services, the results of which are of great importance for maintaining access to and continuity of treatment for OUD, even in non-pandemic circumstances. Continuity of care is critical for patients with OUD, yet inadequate care coordination and early treatment dropout is common even under non-pandemic circumstances (Samples et al., 2018; Williams et al., 2019). Ensuring ongoing access to care for people with OUD is even more vital in the context of COVID-19, given evidence that the pandemic may have contributed to drug use and overdoses (CDC, 2020a; Panchal et al., 2020; Slavova et al., 2020), exacerbation of mental health symptoms (Czeisler et al., 2020), and worsened social and economic hardships associated with substance use (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2020). Maintaining access is especially important when it comes to medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD), the single most effective treatment for OUD (Connery, 2015; Sofuoglu et al., 2019). Policies that maintain access even when the ability to access in-person care is challenged, whether by epidemics, natural disasters or personal circumstances, are also important long-term considerations in maintaining a treatment system that is robust in the face of contingencies that could lead to unnecessary loss of life through treatment disruptions.

In response to the need to reduce in-person interaction in 2020, federal and state authorities implemented several temporary regulatory changes affecting MOUD treatment. These regulations impacted prescribers across treatment settings, including those in methadone-dispensing opioid treatment programs (OTPs), as well as office-based addiction treatment (OBAT) providers and those working in non-OTP specialty treatment clinics. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA, 2020a) implemented temporary flexibilities allowing for increased take-home methadone supply of up to 28 days for stable patients and 14 days for less stable patients. In New Jersey (NJ), the Division of Mental Health and Addiction Services (NJDMHAS, 2020), NJ's Single State Authority for Substance Abuse, issued more-detailed criteria for determining take-home supplies, while still allowing providers a great deal of flexibility. The Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) temporarily waived a provision of the Ryan Haight Act of 2008 that required an in-person initial medical evaluation by any practitioner issuing a prescription for a controlled substance. This waiver now temporarily permits buprenorphine prescribers to use telehealth (including telephone only) for the initial patient visit (SAMHSA, 2020b). Subsequent federal and state guidance allowed for additional flexibility in MOUD treatment including expansion of mid-level provider prescribing capabilities, cross-state prescribing, permission to use any non-public facing videoconferencing products, and changing reimbursement structures, including payment parity for services delivered via telehealth and in-person (Center for Connected Health Policy, 2020; Long, 2020; SAMHSA, 2020b).

There is a need to understand how MOUD providers implemented these flexibilities, their experiences with these adaptations, and their views on which changes should be sustained long-term. Prior studies have described clinicians' experiences early in the pandemic (e.g., Uscher-Pines et al., 2020), but much remains unknown about how providers adapted their practices in the period after the initial changes had been implemented and how patients, clinics, and providers were affected over the months to follow. Capturing provider experiences with these changes is critical for informing future MOUD practice, both during recurring COVID-19 infection peaks and beyond.

1.1. The current study

This study sought to understand the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on MOUD treatment through in-depth interviews with MOUD treatment providers in NJ, a state that has been especially hard hit by both COVID-19 and the opioid crisis (Bean, 2020; CDC, 2020b). Study aims were to: 1) Describe MOUD practice changes induced by the pandemic; 2) Understand provider experiences with those practice changes; and 3) Elicit provider perspectives on which (if any) changes should be sustained long-term.

2. Methods

2.1. Recruitment and eligibility

We used purposive sampling to capture a broad range of provider experiences. Based on lists of active NJ MOUD practitioners, we generated a pool of 12 OTP and 58 OBAT providers from which to recruit for the study. Maximum variation sampling (Palinkas et al., 2015) generated a sampling frame of providers that varied based on treatment setting (e.g., OTP, OBAT); provider type (MD, APN, PA); geographic location and prevalence of COVID-19 infections in the community; characteristics of the patient population (e.g., race/ethnicity, age); and practice size. We recruited potential respondents by email and/or phone from the sample lists, supplemented by additional targeted outreach to assure inclusion of diverse provider types. Recruitment continued until we achieved the goal of 20 providers, at which point we reached thematic saturation and additional interviews would not likely reveal significantly new information. To be eligible for the study, respondents had to: 1) be an MOUD prescriber or other practitioner employed in a treatment setting with detailed knowledge on MOUD and related practice changes during COVID-19; and 2) the respondent or clinic they represented had to prescribe MOUD at the time of interview and prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants received a $200 gift card in recognition of their time and effort.

2.2. Data collection

The study employed a pragmatic qualitative inquiry framework (Patton, 2014). We developed a semi-structured interview guide based on an environmental scan of MOUD practice changes during COVID-19 and through consultation with a Stakeholder Advisory Board, comprised of clinical, policy, and payer experts across NJ. Interview domains included: telehealth (defined here as two-way, real time telephonic or video communication), prescribing practices, OTP practices, staffing and clinic procedures, and overall impact of COVID-19 (see interview guide in supplementary materials). Following the first two interviews, we made minor changes to the interview guide to avoid redundancy and streamline the interview. Interviewers were three graduate-level study team members with expertise in qualitative health services research, who completed interviews between September and November of 2020 using phone or video conferencing software. Interviews lasted approximately 1 h and were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim with identifying information removed.

2.3. Analysis

We employed a rapid analysis approach (Hamilton, 2013; Taylor et al., 2018). We developed a domain summary template containing a priori domains derived deductively from the interview guide as well as space to add domains that emerged inductively during analysis. Three trained analysts coded the first three transcripts independently to test the template, and the team then assessed coding for consistency by examining the level of detail captured, use of quotes, and categorization of information across domains. Team discussions resolved discrepancies in styles to generate a consistent approach. Each transcript was then assigned a primary and secondary coder; the primary coder conducted the initial round of coding and produced the transcript summary while the secondary coder carefully reviewed the transcript and summary to ensure all relevant content was captured. Discussions between the primary and secondary coders resolved coding discrepancies and involved a third study team member when needed. We then analyzed domains for recurring concepts and themes (Hamilton, 2013), as well as potential differences between provider types. The study team produced memos for each domain and met frequently to discuss memos and themes both within and across concepts.

3. Results

A total of 20 MOUD providers (6 OTP and 14 OBAT) completed interviews (Table 1 ). Physicians comprised 45% of the sample, nurse practitioners made up 25%, and the remainder were non-prescribing behavioral health clinicians (e.g., psychologist, social worker). Practice specialties of prescribers were predominantly primary care (50%) and psychiatry (36%). Participants represented OTPs, private practices, community medical and mental health centers, and non-OTP OUD treatment facilities, and were located in urban and suburban communities. Respondents varied in the number of MOUD patients treated in their clinic, ranging from less than 30 to over 500.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics (N = 20)a.

| Characteristic | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Participant | ||

| Female | 10 | 50% |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Black or African American | 2 | 10% |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 2 | 10% |

| White | 12 | 60% |

| Other | 4 | 20% |

| Profession | ||

| Physician | 9 | 45% |

| Nurse practitioner | 5 | 25% |

| Other (e.g., psychologist, master's level practitioner) | 6 | 30% |

| If physician or nurse practitioner, specialty | ||

| Primary care | 7 | 35% |

| Psychiatry | 5 | 25% |

| Other | 2 | 10% |

| Clinic/practice | ||

| Setting | ||

| Opioid treatment program (OTP) | 6 | 30% |

| Solo or group private practice | 7 | 35% |

| Non-OTP SUD treatment facility | 2 | 10% |

| Community medical or mental health center | 4 | 20% |

| Hospital-based or affiliated health clinic | 1 | 5% |

| Urbanicity | ||

| Urban | 7 | 35% |

| Suburban | 12 | 60% |

| Both; multiple locations | 1 | 5% |

| Average # MOUD patients in past 12 months | ||

| Less than 30 | 5 | 25% |

| 30–74 | 2 | 10% |

| 75–124 | 4 | 20% |

| 125–274 | 3 | 15% |

| 275+ | 6 | 30% |

| Clinic MOUD prescriber typesb | ||

| Physician | 19 | 95% |

| Nurse practitioner | 18 | 90% |

| Physician's assistant | 1 | 5% |

In cases where more than one person participated in the interview, only characteristics of the primary respondent are reported.

Percentages exceed 100% because respondents could select more than one MOUD prescriber type in their clinic/practice.

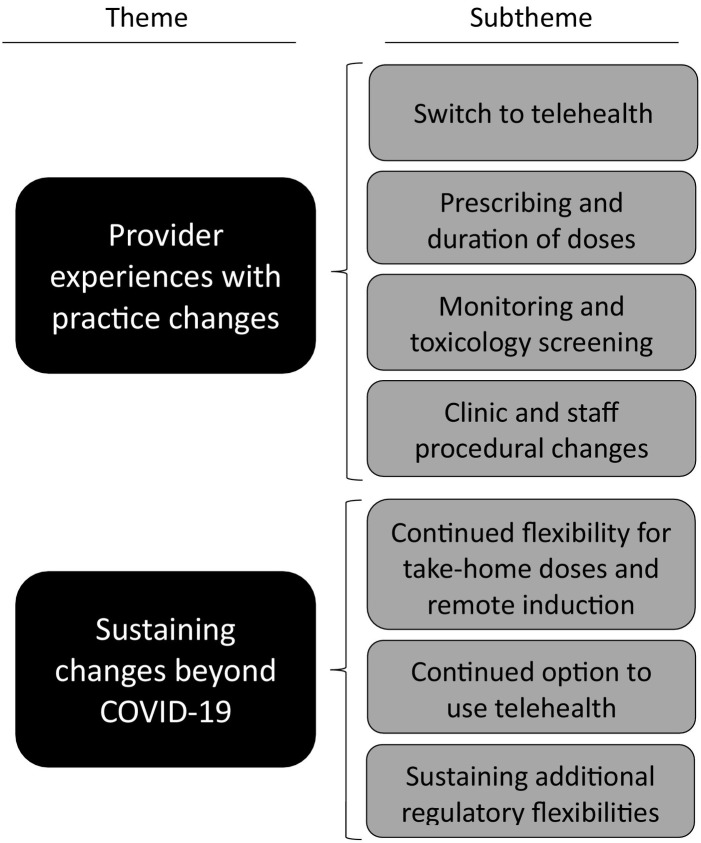

Results were organized into two broad themes based on project aims: provider experiences with practice changes; and sustaining changes beyond COVID-19. These broad themes were the domains of analysis, predetermined by our analytic approach. Each theme contains detailed sub-themes that emerged during analysis of the broader themes (Fig. 1 ). Exemplar quotes are provided below and supplementary quotes are shown in Table 2 .

Fig. 1.

Themes and subthemes.

Table 2.

Exemplary quotes organized by subtheme.

| Theme | Quote |

|---|---|

| Practice changes and provider experiences | |

| Switch to Telehealth |

“So, we're not 100% requiring telehealth, but we are absolutely making it available to as many patients as are able to take advantage of it and who we feel comfortable with that type of communication as opposed to in-person” (OTP3). “But I think there's something to be said to speaking to somebody that's sitting in the comfort of their own living room at their couch… There's a lot of contextual information that I think we can get as providers by watching people in their home environment that I think is really positive” (OBAT12). “[Telehealth] helps with the stigma, that being able to access from the privacy of your home they don't have to deal with the stigma of going to a clinic” (OBAT4). “I feel, [telehealth] kept the patients safer from relapsing because of the ways that we can engage the patient through the telepsychiatry” (OBAT1). |

| Prescribing and duration of doses |

“Our nurses are doing a great job because every week they look at, okay, who's doing well, how many take-home bottles a week. It's really assessing them individually. Are they actively participating? Do we have any concerns or they have a safe place?” (OTP1). “There might've been a fair amount of loosening between two weeks and a month in say March and April into May, but like since say May or June we're business as usual… COVID had a very minor and very temporary impact” (OBAT4). “[We need] better control of our patients because of the stresses of COVID, and the medication is the best control that we have… So we've been seeing them more frequently. We've been limiting prescriptions to no more than one month. So there are no refills on prescriptions” (OBAT11). |

| Monitoring and toxicology screening |

“We did slack a little bit… we give some leeway toward more stable established patients” (OBAT10). “The urine and drug screens have been challenging, but I really try to… Again, one, is we've sent people to just [outside lab provider], what have you, and done them that way, which I think is actually more than sufficient honestly because we're not watching. We're not doing witness. We're not a court system. We're not going into the bathroom with people, and so if they go to [outside lab provider], [outside lab provider] probably has more of a workflow than our offices do. They're going to have a routine to it” (OBAT13). |

| Clinic and staff procedural changes |

“We never stopped admissions. It was a brief period … I'm going to say maybe two to three weeks where we stopped inpatient admissions because we just had to come up with some protocols… We never stopped out-patient admissions. We decreased them, but we never stopped them” (OTP4). “Everything is running as per usually and we're still just wearing masks, sanitizing, PPE, just in that very rigid sanitization schedule” (OTP2). |

| Sustaining Changes Beyond COVID-19 | |

| Continued flexibility for take-home doses and remote induction |

“We didn't see a whole bunch of people just die. I mean, that certainly was our fear, like, ‘Oh, my God, we're going to give all these people take homes. Within a month, they're all going to be dead.’ That didn't happen. So, that was good” (OTP3). “I would love to keep the increase in take-home bottles, I would have loved to keep the change in testing too” (OTP6). “But at the end of the day, a regulatory requirement that we must see people face-to-face for that visit, there is no question that there are people that will not be able to access care during that windowed timeframe. There will be people that overdose and die because, I mean, that will happen. We strongly advocate for that not being reinstated and that we are able to continue to deliver care” (OBAT12). “I think the biggest thing is around deregulation, around access that the DEA doesn't then require them to do the first time face-to-face. I think that's the biggest thing. That's the biggest thing. That was the biggest game-changer in my mind” (OBAT13). |

| Continued option to use telehealth |

“Trying to get patients into a practice for care is simply not necessary for many, many, many diagnoses. And this is one of them. In fact, I will go so far as to say many patients likeneed that little bit of anonymity that first approach to telehealth allows and permits. So what I would do is offer it to the patient. And many patients jumped on it” (OBAT9). “We just decrease the number of barriers to getting somebody into care. I think that's been probably the most transformative thing” (OBAT12). “People are able to have their visits during the day, and not have to worry about if they have to have an afternoon … I really think it offers my clients a little more freedom. Those who work and have children, a little more freedom to express themselves and for them to give me information that I would not have known” (OBAT14). |

| Sustaining additional regulatory flexibilities |

“[Licensing rules make it] so difficult to deliver the integrated care model that we want to deliver” (OBAT12). “I think it would be reasonable to allow the counselor interns to just do telehealth, period. They're still supervised, they're providing the same service that they are live, so I'm not sure why they're not allowed to provide it via Telehealth” (OTP5). |

3.1. Provider experiences with practice changes

3.1.1. Switch to telehealth

Prior to COVID-19, few providers we interviewed utilized telehealth for MOUD patients, for reasons that included unclear regulations and inadequate reimbursement. At the onset of COVID-19, most providers reported immediately transitioning most of their services to telehealth. Several providers said they “never had a time where we weren't seeing patients in person” (OBAT1) because they did not want to diminish access, even if services were provided via telehealth once at the office. In-person care remained available in OTPs for induction and medication dispensing, but most other services were conducted via telehealth starting in March 2020. Providers offering both in-person and telehealth services determined the appropriate modality based on several factors, such as patients' vulnerability to COVID-19 or risk of relapse. For some providers, the move to operating entirely via telehealth was temporary and maintained only while they outfitted their offices for safety, while others continued to provide fully remote services.

Counseling services provided alongside MOUD, available in approximately half of facilities whose staff we interviewed, were profoundly impacted by COVID-19. Many noted they ceased group counseling altogether at the start of the pandemic, while individual counseling continued primarily by telehealth. Some subsequently resumed group counseling using a combination of in-person and telehealth options, depending on patients' preferences and access to technology. “We're following the hybrid model in which we assess the client's needs and the resources that they have, and based on that, we offer either an appointment for virtual services or they can come in” (OTP1).

Most respondents viewed the shift to telehealth positively, stating that the ability to work from home saved commuting time, allowed them to see patients more efficiently, and made childcare easier. Others, however, noted downsides of remotely delivered care, including that patients relied on them more heavily and during off-hours. “They'll call at like 1:36 at night, ‘I'm having a panic attack. I need to talk to you,’ and I answer and we talk” (OBAT6). Across provider types, telehealth was said to make patient scheduling easier, since patients did not have to build in time to get to and from the office and appointments were less likely to be delayed or canceled. Providers reported differing perspectives on the impact of the changes on their ability to coordinate and provide team-based care. Some felt the shift to remote care brought their professional teams closer, demonstrated how well their staff worked together to address challenges, and facilitated care coordination. Others, however, felt that remote work negatively impacted staff productivity, caused staff to feel isolated, and made consultations and informal case discussions with colleagues more challenging. As recounted by one participant, “I actually think we have staff members that still have not met each other in person just because it hasn't worked out that way. It changes the dynamic” (OBAT12).

Providers reported that telehealth removed barriers for many patients by allowing them to connect to care from where they are. This was seen as especially critical for patients with transportation or childcare needs, those who lived far away from their providers, and patients with work schedules that made daytime appointments difficult. “I think that's a really big deal because there's so many socioeconomic things that get in the way when people are trying to get time off work and come to an office, even just geographic barriers that aren't an issue when we're doing telehealth” (OBAT5). The flexibility of telehealth as it related to patients' employment stability was important for providers, as maintaining employment was often an important aspect of recovery. “If someone's working I definitely think that's part of their recovery and so, I want to try to minimize any disruptions to their work schedule. And I think that the telehealth provides a little bit more flexibility in that regard” (OBAT8). The successes that some providers experienced was supported by telehealth payment parity, which allowed them to spend more time checking in with patients via phone, a practice that was cost-prohibitive before the pandemic. “I'm able to see my patients right now every two weeks as opposed to every four to eight weeks” (OBAT8). Several providers discussed telehealth as improving their retention and engagement rates, as it reduced patient access barriers and allowed for more frequent contact. A few providers described an unexpected benefit of telehealth as allowing them to see and assess patients' living environments.

On the other hand, the shift to telehealth was reported by some respondents as being detrimental for certain patients. Technological limitations were a particular challenge, either because patients were not tech-savvy or because they did not have the technology or data allowance to access telehealth platforms. “The internet service is not good. If they want to use the phone, for example, they pay for the minutes on their cell phone and they're worried about how much this is going to cost” (OTP1). Other patients had difficulty finding a private place for telehealth appointments or distractions in their environment that interfered with communication. For some patients, the clinic was a “safe haven” that gave them a place to “stop by and meet with the case manager… or hang out and get coffee or whatever” (OBAT5), so losing it was akin to losing a pillar of recovery.

Respondents shared that patients and providers alike missed the face-to-face contact they had before the pandemic, which they felt was important for building rapport and forming connections. “I miss the personal aspect of it. You know, I've been in healthcare [for decades] and, to me, [losing] the face to face, the eye contact, and being able to touch and feel on your own, that's a drawback” (OTP4). Providers also shared that some specific aspects of care were ill-suited for a telehealth environment. Assessing and monitoring patients was reportedly more challenging, especially when using telephone rather than video platforms. “With mental status examination, a lot of that's observational. I actually want to see my patients. It sounds silly but I want to be able to smell my patients. If they're not taking care of themselves, if they look disheveled, I can't get that from an audio assessment” (OBAT8).

3.1.2. Prescribing and duration of doses

All but one OBAT provider reported no changes to the type of medication prescribed to patients due to the pandemic. Regarding prescription days' supply, most OBAT providers reported little to no change for naltrexone and buprenorphine, largely because telehealth allowed for visits with the same frequency as in-person care. “We're able to do the number of visits, in theory, if patients will show, that we would if we were doing in person. It hasn't caused us to change that” (OBAT12). Other providers who reported changing their prescribing patterns varied in their approaches. Early on, some issued prescriptions with greater days' supply or issued early refills due to uncertainty around the course of the COVID-19 pandemic; others shortened the days' supply for patients early in the pandemic because they wanted to “keep an eye on” patients who were thought to be at high risk of relapse and overdose. Almost all providers whose prescribing practices changed reported that these were temporary and occurred early in the pandemic when they had to rapidly adapt to changing circumstances. A few participants noted that they had not used electronic prescribing before the pandemic but shifted to this practice following the onset of COVID-19. One prescriber employed in a larger specialty treatment clinic felt this change was long overdue: “Nothing except COVID made that possible. We've been asking for that for five years” (OBAT11).

Despite the regulatory flexibilities permitting telehealth initial buprenorphine visits, approximately half of OBAT respondents elected to continue in-person initial evaluations during the pandemic. Some indicated that the practice was simply not consistent with the way they historically treated patients. One provider emphasized the importance of in-person visits to complete an initial drug screen due to “risk of seizures and other issues” (OBAT3) when patients are using other substances such as benzodiazepines. Others indicated that lack of clarity around regulations made them apprehensive about conducting remote evaluations. “If you look at the guidelines, they're very inconsistent. We've reached out to the DEA for clarification, and we've gotten two different stories or answers, so we personally chose not to do it” (OBAT6). A few providers who continued in-person evaluations did so because they were licensed by the state as ambulatory withdrawal management clinics and were not permitted to conduct home inductions.1

Approximately half of OBAT providers conducted fully remote initial visits for some or all new patients since the onset of COVID-19, for reasons including concern for patient and staff safety; desire to remove barriers to MOUD utilization; or because they operated a fully remote practice. “Even if we haven't been able to complete our initial assessment [in person], we don't let that get in the way of prescriptions” (OBAT4). Among these providers, most reported increasing follow-up patient contacts beyond their normal practice in the days and weeks after induction: “The follow-up is a lot more, I guess because we're not meeting in person, that we want to be more sure of how they're doing” (OBAT2). Some providers who did fully remote initial evaluations during NJ's COVID-19 peak in the spring of 2020 had returned to a hybrid practice for induction at the time of the interview, but indicated they would remain flexible in the event of recurring peaks. None of the providers who conducted remote initial visits reported unintended consequences (e.g., precipitated withdrawal, diversion) of this modified approach and most did not see the need to conduct in-person initial visits in all cases.

OTP providers' responses to the regulatory changes around medication supply varied as well; while some fully applied the pandemic-induced regulatory flexibilities, others took a more conservative approach. One OTP provider “markedly increased the ability of our patients to get take-home methadone” (OTP3), adjusting their protocols to provide take-homes to many patients who otherwise would not qualify. Other OTP providers stated they issued additional take-homes for many of their patients early in the pandemic but soon retreated, believing that state flexibilities exposed patients and providers to greater risk. “Our corporate compliance person was just like ‘We've got to give them, we've got to give them.’ I'm like ‘I don't feel comfortable.’ So, as the weeks went by, we just kind of went back to our old process” (OTP4). Although most providers gradually reduced the flexibilities as new procedures were established, take-home schedules generally remained more flexible than they were prior to the pandemic, but less so than in the early months.

Of OTP respondents, a few noted that, unexpectedly, the increased take-home doses permitted during the pandemic seemed to increase adherence to treatment; patients who initially got extended take-home supplies due to the pandemic soon became eligible for take-homes even by pre-pandemic criteria. “This was the most surprising thing… getting the take-home medications that they have not earned, actually motivated them to change that they are now meeting the criteria… So that for them it's no longer a pandemic bottle, it is another bottle that I have earned” (OTP6). Other OTP providers viewed the loss of rigidity in the structure of appointments and requirements for take-home bottles negatively. “As a contingency management tool, we've lost the ability to grant or remove take-home dosages from patients, either as an incentive for doing better or as something they would lose if they did worse. So, we've definitely lost a lot of tools” (OTP3). A few reported that they had anticipated the increase in take-home doses would have caused more problems – including diversion and overdoses – than it did. “Our initial thinking that it was just going to be a complete mess… and it ended up not turning out that way at all” (OTP2). No providers reported an increase in overdoses among their patients since the onset of the pandemic, and some observed a decrease.

3.1.3. Monitoring and toxicology screening

Historically, treatment providers have used toxicology testing to monitor patient drug use, although in OBATs particularly, testing was increasingly viewed as less essential and conducted relatively infrequently even before the pandemic. During NJ's severe first wave of COVID-19 in the spring of 2020, testing was noted to be either stopped completely or severely limited for many providers, given difficulties in seeing patients in-person. OBAT providers said that toxicology testing “took a back seat” and it became more about “making sure these folks don't go back out, relapse and overdose” (OBAT7). Several interviewees stated that the inability to see patients in clinical sites impacted the practice of random toxicology screenings, which was more common before COVID-19. Interviewees reported that testing levels gradually returned to pre-pandemic levels after the initial pandemic surge in Spring 2020.

Changes in testing modalities also occurred during the pandemic. “The biggest problem was trying to get urine testing, that was the problem for us… Because we're prescribing medications, but we're not getting the urines that we wanted to get” (OBAT7). Many OTP and OBAT providers introduced oral swab testing at the beginning of the pandemic to either replace or complement urine testing. In some cases, providers switched from urine to oral testing to avoid the challenges clinic staff faced while monitoring urine collection. Oral swabs allowed for reduced clinic volumes, as several OTP respondents reported using the oral swabs for testing while conducting curbside dosing. A few interviewees expressed concerns that oral swabs were not as reliable as urine toxicology screens and shifted back to urine testing. Some practices implemented other changes to facilitate continuation of testing safely and effectively, such as introducing remote testing modalities to get samples during telehealth appointments, which included mailing urine or oral testing kits to patients' homes and asking them to show results during a video visit. A few providers observed increases in drug use in their patients, primarily of alcohol and marijuana, and expressed that this could have been in part due to decreased drug testing.

OTP respondents described a range of steps to monitor patients' use of medication and minimize diversion when providing extended take-home methadone supply. Most reported using medication “callbacks,” which require patients to return empty methadone bottles to the clinic for staff to count. One provider reported using “virtual callbacks” by asking patients to display their remaining supply on camera to “see the number of bottles that they have at any given time” (OTP3). Other means by which providers monitored patients included periodic toxicology testing, monitoring for changes in speech and demeanor, assessing for over-sedation when observed doses were given at the clinic or remotely observed, and conducting regular wellness calls. When OTP providers we interviewed became concerned that patients were not adhering to treatment and could not properly assess adherence virtually by the means described above, patients were required to visit the clinic more frequently.

3.1.4. Clinic and staff procedural changes

All providers indicated that they imposed standard CDC guidelines for public accommodations during the pandemic, such as increased mask requirements, Plexiglas barriers between staff and patients, social distancing, temperature checks for staff and patients, and symptom questionnaires for patients. Many providers strictly limited numbers of patients in the building at a time through staggering appointments; reconfiguration or elimination of the waiting room; extending office hours; suspending group counseling; and/or providing curbside, in-vehicle, or outdoor dosing. One provider whose employer took steps to implement recommended guidelines noted how much they appreciated the efforts: “I feel like our agency is being more on the conservative end and I have really appreciated that. I think they've kept everyone feeling really safe” (OBAT5).

OTP providers reported that staffing levels remained fairly stable throughout the pandemic, but that state licensing regulations initially prohibited counselor interns from delivering telehealth, placing additional burden on fully credentialed staff members. This burden was eased, however, when the Division of Consumer Affairs issued regulations permitting counselor interns meeting certain experiential and educational requirements to deliver telehealth (NJDCA, 2020). A few OTP providers noted that some staff were either voluntarily or mandatorily furloughed, though not permanently laid off. OBAT practices seemed to have a more difficult time maintaining staffing levels during the pandemic. Two OBAT respondents reported permanent reductions in staffing and one interviewee indicated that the staffing reduction may have impacted patients, noting that they had not been able to fill vacancies left by the turnover. “There was times where there would be just one provider for the whole office” (OBAT2). Across settings, most providers reported minimal changes in patient capacity because of COVID-19. Although a few respondents briefly paused new admissions early in the pandemic, nearly all resumed admitting new patients within weeks.

Most providers reported that the pandemic and the need to change procedures created financial challenges due to lost revenue from delayed reimbursement, lower reimbursement for telephone-only visits (for certain payers), and increased costs from purchasing remote work technology (e.g., laptops), cleaning materials, and other supplies. “There was a lot of financial costs in the beginning of COVID. They had tremendous financial burdens because they had to have many things in place for COVID, including purchasing protective equipment at a huge rate” (OBAT1). Among providers that included psychosocial services as part of usual care, inability to conduct group sessions in a way that ensured adequate reimbursement (either due to the session length or number of attendees) also substantially reduced revenues.

3.2. Sustaining changes beyond COVID-19

All providers we interviewed expressed a desire for the temporary flexibilities to become permanent, including those allowing for more take-home methadone doses in OTPs without meeting the existing stringent criteria; the ability to conduct a remote initial evaluation for patients starting buprenorphine; and the ability to provide services via phone or video with reimbursement equal to in-person services. “I think the relative freedom that we have to do what we're doing now is a huge advantage and I would like to see that carried through, because I think given the time and given the data, we're going to be able to self-regulate and do what's best for our patients” (OTP3). While consistently expressing support for extending flexibilities, respondents differed in the extent to which they planned to modify their own practice long-term, with some providers expressing concern that the federal and state regulatory changes could have negative, unintended consequences. Providers agreed that retaining the flexibilities beyond COVID-19 would improve access to and quality of care, but some suggested that their MOUD treatment approach would ultimately look more similar to the pre-pandemic approach than that implemented during COVID-19. Notwithstanding this, giving providers the flexibility to adapt treatment processes to individual patient circumstances was seen as an important tool to allow providers to improve care for their patients.

3.2.1. Continued flexibility for take-home doses and remote induction

Respondents at OTPs generally saw the criteria for determining take-home doses prior to the pandemic as being too strict, placing limits on providers' ability to use their clinical judgment to guide their decision-making. “I don't know if there is a need for everybody to wait 90 days or two years [to increase take-home supply]. If you're an individual who's doing well and is progressing well, and is able to achieve their goals pretty quickly. More individualized treatment, not these regulations that everybody has to wait this number of months prior to moving up in phase” (OTP1). While all thought it was important to continue to allow greater flexibility, they varied in their plans for future practice with respect to take-home supply and most did not use the flexibilities to their maximum extent. For example, several OTP providers indicated that they now preferred to use take-home schedules somewhere between the pre-pandemic guidelines and the maximum flexibility temporarily allowed during the pandemic. Still, even these providers thought the pre-pandemic guidelines were too rigid, and that loosening them would allow them to better tailor treatment to individual needs. Thinking about what might happen if SAMHSA temporary regulations are lifted, one provider expressed concern over transitioning patients back to the pre-pandemic take-home schedules: “I don't know how to get back to normal. How do you get back to telling people ‘No, you've got to come on Saturday to dose?’” (OTP4).

Prescribers in OBAT settings consistently expressed support for permanently allowing buprenorphine prescriptions without an initial in-person patient examination; respondents preferred the option of having the initial visit via telehealth, even if they elected not to do so. “You had to do the face-to-face induction before, and now you don't. And I think, even though I still do the face to face, knowing that I don't have to do that is nice” (OBAT3). Some thought reinstating the in-person requirement would be detrimental and unnecessary, preventing some people from accessing needed treatment. The flexibility allowed during the pandemic to permit induction via telehealth was seen as a key aspect of patient-centered, lower-threshold treatment that is important to include in regulations going forward.

3.2.2. Continued option to use telehealth

All providers wanted the option of continued use of telehealth, noting that “the more options we have, the better we can serve our population” (OTP1). Providers emphasized that it would be important to ensure that reimbursement for telehealth is equivalent to in-person services, or providers would hesitate to continue using it. Providers generally wanted to be able to determine the best modality for their patients, with (comparably reimbursed) telehealth visits as one option. “I think telehealth is just another tool. It's just another option. Do I think it should replace face to face? No. Do I think it should not be used at all? No. I think it definitely has a place” (OBAT3). The option was seen as enabling more individualized care and potentially improving access for hard-to-reach populations.

For the future, providers envisioned treatment models that varied in the extent to which patients would be seen in-person versus via telehealth, but all favored a hybrid model. Although many providers supported the option of telehealth, they were eager to return to in-person care. Some indicated that they would ultimately return to a mostly in-person format, citing the importance of the office environment in making patients feel comfortable, the relational aspects of in-person care, and providing a routine for patients. Practitioners working in settings providing group counseling in addition to MOUD especially expected to return to greater use of in-person services, as virtual groups were said to be a challenge and barrier to peer-to-peer interaction. “We tried to run an IOP virtually, and that didn't go well because you had people sitting in their car, people sitting at work, and at home with their kids, and it's just very difficult” (OTP1). The common thread throughout the interviews was that respondents emphasized that they would prefer to determine how to see patients on a “case-by-case basis” (OTP5), depending on individuals' specific circumstances, resources, and needs.

3.2.3. Sustaining additional regulatory flexibilities

Some providers noted that the loosening of cross-state practice regulations during the pandemic was helpful and hoped these would continue. As described by one respondent, “I have a provider in [neighboring state] that wants to work for us. I can get her onboard so much more quickly right now because she can get an emergency provision under the state of New Jersey to start practicing whereas getting a full-blown New Jersey license takes months and months to do” (OBAT12). Another respondent noted that the waiver of the requirement for a collaborative physician for nurse practitioners has been useful during this time. Most providers were conducting toxicology tests regularly at the time of our interviews and thought continuing drug testing was important to ensure patients were taking medication as prescribed and to monitor for other substance use. Some respondents, however, noted that while toxicology testing was an important clinical tool, providers should be able to determine frequency without concern of legal ramifications.

4. Discussion

Results support the continuation of the federal MOUD flexibilities into permanent policies that allow for a more flexible, individualized approach to providing MOUD. We found a clear consensus, based on providers' experience with the COVID-19 era “natural experiment” of regulatory waivers, that the temporary flexibilities should be made permanent. While varying in the extent to which they preferred to apply the flexibility, all providers interviewed expressed a desire for federal policies to continue allowing expanded use of telehealth (including remote initial evaluation for patients starting buprenorphine and the option of audio as well as video platforms); the ability to flexibly adjust the use of take-home doses of methadone in OTPs; and reimbursement for telehealth on par with in-person visits. In light of experience with the COVID-19-era flexibilities, pre-pandemic federal regulatory restrictions were generally seen as overly rigid, burdensome, and unconducive to individualized, person-centered treatment processes. In their future practices, many providers envisioned being able to provide treatment on a hybrid model, adaptively using both telehealth and in-person strategies to provide individualized treatment, reducing barriers to treatment retention while maintaining accountability on a personalized basis.

These views are consistent with those of many clinical and policy experts, who have suggested that the recent changes represent long-overdue reforms that have the capacity to substantially improve service delivery even in the absence of a public health emergency, and have called for the temporary flexibilities to be made permanent (e.g., Davis & Samuels, 2020; Moran, 2020). The Ryan Haight Act requirement for in-person evaluation prior to controlled substance prescribing, for example, has been cited as a barrier to MOUD treatment, especially among individuals living in rural areas and those with disabilities and transportation barriers (Andrilla et al., 2017). Respondents in our study said that waiver of this requirement during COVID-19 helped hard-to-reach populations access care and supported permanent reform. Although few providers we spoke to (other than those operating fully remote practices) had plans to conduct initial visits solely via telehealth, all thought the option to conduct initial visits via telehealth was critical for ensuring that patients could engage in care at “windows of opportunity” when patients were motivated to begin treatment. Even if the application of the Ryan Haight Act to buprenorphine is not repealed, provision for emergency temporary induction followed by subsequent in-person evaluation could help in reducing overdose risk that can occur while a new patient is awaiting an appointment.

Telehealth has for several years been proposed as an important strategy for expanding access to MOUD (Yang et al., 2018). Our interviewees, most of whom had never used telehealth in their practice before the pandemic, universally agreed that the option to use telehealth improved patient care, especially for those unable to attend frequent in-person visits. Nevertheless, prior studies (e.g., Hughto et al., 2020; Kruse et al., 2018) have reported that numerous barriers to telehealth adoption – such as patients' lack of technology and insufficient reimbursement – can limit patients' access to needed treatment, and our findings were in agreement. Our interviewees were unanimous in advocating for maintenance of telehealth flexibilities, provided they were able to decide whether to utilize such flexibilities for individual patients.

Some respondents reported the need to overcome technical challenges to the use of telehealth in some cases. These finding suggest that policy changes permitting telehealth for MOUD should also be accompanied by investments in training, infrastructure, and equipment to facilitate the use of telehealth (Drake et al., 2020). This is particularly important for high-need patients who often have the fewest resources, such as access to computers, cell phones, and high-speed internet required for video communications. Efforts to permanently expand modes of care relying on advanced technology must be carefully designed so as not to further widen existing racial/ethnic and economic disparities in care access and utilization. A few providers expressed challenges around coordination and collaboration when working remotely; further development of software and other tools to facilitate secure provider communication could help address this challenge.

As providers in our study noted, for telehealth to be utilized it is critical that it be reimbursed at the same rates as in-person care, a requirement for payers in only seven states as of 2019 (Kwong, 2020). The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), state Medicaid agencies, and many private payers, have approved equivalent reimbursements for telehealth services during COVID-19 (Goldman et al., 2020), but approvals will need to continue for these services to be financially viable beyond the pandemic. An additional implementation challenge raised by our participants related to drug testing, which was generally described as a useful clinical tool but difficult to carry out without in-person visits. Providers noted that oral swab tests could be mailed to patients and viewed during a video visit, but many were concerned about the accuracy of such tests and their capacity to detect buprenorphine. Further development of drug testing technology and collection methods could help in addressing this challenge.

There is a need for additional research to evaluate the policy and practice changes occurring during COVID-19 (Del Pozo et al., 2020; Nunes et al., 2020). Our interviewees' reports suggest that more-flexible models do not reduce care quality or worsen patient outcomes, and may even be beneficial to patients with the ability to access care through telehealth. Important areas to be addressed by future research include whether models of care that reduce barriers to treatment entry lead to greater treatment initiation and retention; comparative effectiveness of telehealth and in-person care; unintended negative consequences of flexible care models and whether these outweigh benefits; risks and benefits of increased take-home methadone; and the impact of flexibilities on diversion. Federal funding prioritizing these areas of research would support timely results made possible by the natural experiment brought on by the pandemic. Given the many MOUD policy and practice changes taking place during COVID-19, there is a need to learn from these experiences in developing guidelines and practice recommendations specific to telehealth delivery of MOUD to promote high standards of care (Lin et al., 2020). Our interviewees reported a great desire to incorporate flexibility into their practices after COVID-19, and it will be critical to understand for whom and in what circumstances each modality is most appropriate. With greater practice flexibility in place, it will also be important to develop mechanisms for holding programs, payers, and providers accountable for high quality care (Goldman et al., 2020). Different health care payment structures for MOUD services may be able to create incentives for providers to use the modality that best serves the patient, but would require further development of quality measures and mechanisms for efficient collecting and reporting.

Methadone treatment in the US remains highly restrictive, with requirements for daily clinic attendance for many patients. Interviewees in this study working in OTPs universally agreed that regulatory flexibilities regarding take-home methadone supply should continue beyond the pandemic. Researchers and advocates have called for reform in this area to increase access to treatment, including permitting methadone prescribing in primary care clinics and pharmacy-based methadone dispensing (Del Pozo & Rich, 2020; Joudrey et al., 2020; Kleinman, 2020). Experiences of countries that allow methadone prescribing in less restrictive settings have shown that it can be done safely for the overall benefit of patients, providers, and communities (Samet et al., 2018). Promising technologies for technology-assisted methadone dispensing, such as electronic pillboxes that deliver split-doses (Dunn et al., 2020), could be deployed more widely to reduce likelihood of misuse with increased take-home supply.

Diversion is frequently cited as a reason for continuing strict regulation of MOUD; however, interviewees did not see evidence of increased diversion with loosened regulations in place during COVID-19. After a brief period of relaxation early in the pandemic, providers we spoke to generally quickly resumed their usual monitoring activities (e.g., medication callbacks for methadone and drug testing for buprenorphine) and felt that any efforts to reduce diversion were unaffected by the relaxed regulations. To the extent that concerns about diversion compete with efforts for prompt, low-barrier buprenorphine induction, it is relevant to note that many studies suggest that diverted buprenorphine is most often used to manage withdrawal symptoms rather than as a primary drug of abuse (Chilcoat et al., 2019), and could indeed be seen as a form of self-treatment (McLean & Kavanaugh, 2019). In a Baltimore survey of injection drug users, 91% of those using street-obtained buprenorphine did so to manage withdrawal symptoms, while recreational use was rare (Genberg et al., 2013). One study found that people who had used non-prescribed buprenorphine more frequently in the past six months were less likely to experience a drug overdose during that same time period, suggesting a potential harm reduction consequence of diversion (Carlson et al., 2020). A German study found that motives for the non-prescribed use of medications used to treat OUD were mostly related to potential shortcomings of formal MOUD, such as insufficient dosages, difficulties with transportation, and lack of access (Schulte et al., 2016). It has been argued that any benefits from reduced diversion are outweighed by the serious health consequences and fatalities associated with opioid addiction itself (Clark & Baxter, 2013).

Our findings complement those of other recent studies examining COVID-19 impact on MOUD. A qualitative study by Uscher-Pines et al. (2020) similarly found that providers rapidly changed practices in response to the pandemic, and that providers generally initially limited in-person visits, increased the amount of medication given to patients, and waived urine toxicology screening in the initial phases of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our research shows how providers viewed the practice changes after several months of implementation, and how they understood the changes impacted their practices and their patients' experiences with MOUD over that time period. Studies using prescription drug monitoring and health care claims data furthermore show that buprenorphine prescriptions remained stable in the early months of the pandemic, although new treatment initiation may have decreased modestly during this period (Huskamp et al., 2020; Nguyen et al., 2021; Thornton et al., 2020). Findings of these studies are consistent with reports from our 20 interviewees, who noted minimal disruptions in care in large part due to their ability to rapidly adapt service delivery to ensure continuity of care.

It is important to note limitations to this research. First, findings have limited generalizability due to the qualitative nature of our study. Although we utilized purposive sampling to explore a range of perspectives, our sample included 20 providers in a single U.S. state and may not represent other practice models in other states. And while it was not a goal to compare results by respondent type, the small number of interviews made it difficult to assess variations in perspective based on provider characteristics. Additional research with larger samples examining how context and provider characteristics (e.g., practice setting, training, treatment philosophy) influence perspectives could help explain the differences in treatment practice changes observed in this study.

5. Conclusion

While the COVID-19 pandemic placed enormous pressures and burdens on MOUD providers, it also afforded opportunities to implement creative care models and utilize new approaches. Providers generally experienced many changes in practice as positive and all providers we interviewed supported permanently extending the temporary flexibilities imposed during COVID-19, which allows them to tailor the care they provide to the individual patients that they serve as they see fit. Over the course of the study period, some providers chose to use the flexibilities to their greatest degree – issuing, for example, the near-maximum allowable doses of take-home methadone supply – while others elected to use the flexibilities in much more limited circumstances. Still, even those who did not substantially change their approach felt there were certain cases where implementation of the flexibilities increased access to and utilization of treatment. Thus, the availability of the flexibilities was consistently seen as a tool that should be available to allow for more adaptable, individually tailored patient care that could help to maintain access without a decline in care quality.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Rutgers University Institutional Review Board (IRB # Pro 2020000641).

Funding

This work was supported by the Foundation for Opioid Response Efforts, New York, NY; and the National Institute on Drug Abuse [NIDA; 1R01DA047347-01].

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Peter C. Treitler: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Cadence F. Bowden: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Visualization. James Lloyd: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Michael Enich: Investigation, Writing – original draft. Amesika Nyaku: Validation, Writing – review & editing. Stephen Crystal: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Footnotes

Note: Further state guidance was provided shortly after we completed interviews, to clarify that licensed substance use disorder treatment facilities were permitted to conduct home induction of buprenorphine.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108514.

Appendix A. Interview Guide

Supplementary material

References

- Andrilla C.H.A., Coulthard C., Larson E.H. Barriers rural physicians face prescribing buprenorphine for opioid use disorder. Annals of Family Medicine. 2017;15(4):359–362. doi: 10.1370/afm.2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean M. Becker’s hospital review. 2020. COVID-19 death rates by state: Dec. 18.https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/public-health/us-coronavirus-deaths-by-state-july-1.html Retrieved December 18, 2020, from. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson R.G., Daniulaityte R., Silverstein S.M., Nahhas R.W., Martins S.S. Unintentional drug overdose: Is more frequent use of non-prescribed buprenorphine associated with lower risk of overdose? The International Journal on Drug Policy. 2020;79:102722. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Connected Health Policy Telehealth coverage policies in the time of COVID-19. 2020. https://www.cchpca.org/resources/covid-19-telehealth-coverage-policies Retrieved December 22, 2020, from.

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities Tracking the COVID-19 recession's effects on food, housing, and employment hardships. 2020, December 16. https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/tracking-the-covid-19-recessions-effects-on-food-housing-and Retrieved December 18, 2020, from.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Increase in fatal drug overdoses across the United States driven by synthetic opioids before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. 2020, December 17. https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/2020/han00438.asp CDC Health Alert Network.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) CDC wonder. 2020. https://wonder.cdc.gov/ Retrieved November 22, 2020, from.

- Chilcoat H.D., Amick H.R., Sherwood M.R., Dunn K.E. Buprenorphine in the United States: Motives for abuse, misuse, and diversion. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2019;104:148–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2019.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R.E., Baxter J.D. Responses of state Medicaid programs to buprenorphine diversion: Doing more harm than good? JAMA Internal Medicine. 2013;173(17):1571–1572. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connery H.S. Medication-assisted treatment of opioid use disorder: Review of the evidence and future directions. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2015;23(2) doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeisler M.É., Lane R.I., Petrosky E., Wiley J.F., Christensen A., Njai R.…Rajaratnam S. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, June 24-30, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2020;69(32):1049–1057. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis C.S., Samuels E.A. Continuing increased access to buprenorphine in the United States via telemedicine after COVID-19. The International Journal on Drug Policy. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102905. (Advance online publication) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Pozo B., Beletsky L., Rich J.D. COVID-19 as a frying pan: The promise and perils of pandemic-driven reform. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2020;14(5):e144–e146. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Pozo B., Rich J.D. Revising our attitudes towards agonist medications and their diversion in a time of pandemic. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2020;119:108139. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake C., Yu J., Lurie N., Kraemer K., Polsky D., Chaiyachati K.H. Policies to improve substance use disorder treatment with telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2020;14(5):e139–e141. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn K.E., Brooner R.K., Stoller K.B. Technology-assisted methadone take-home dosing for dispensing methadone to persons with opioid use disorder during the Covid-19 pandemic. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2020;121:108197. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genberg B.L., Gillespie M., Schuster C.R., Johanson C.E., Astemborski J., Kirk G.D.…Mehta S.H. Prevalence and correlates of street-obtained buprenorphine use among current and former injectors in Baltimore, Maryland. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38(12):2868–2873. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman M.L., Druss B.G., Horvitz-Lennon M., Norquist G.S., Kroeger Ptakowski K., Brinkley A.…Dixon L.B. Mental health policy in the era of COVID-19. Psychiatric Services. 2020;71(11):1158–1162. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton A.B. Qualitative methods in rapid turn-around health services research. 2013. http://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/video_archive.cfm?SessionID=780 VA Women's Health Research Network.

- Hughto J.M., Peterson L., Perry N.S., Donoyan A., Mimiaga M.J., Nelson K.M., Pantalone D.W. The provision of counseling to patients receiving medications for opioid use disorder: Telehealth innovations and challenges in the age of COVID-19. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2020;120 doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huskamp H.A., Busch A.B., Uscher-Pines L., Barnett M.L., Riedel L., Mehotra A. Treatment of opioid use disorder among commercially insured patients in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;324(23):2440. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.21512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joudrey P.J., Edelman E.J., Wang E.A. Methadone for opioid use disorder – Decades of effectiveness but still miles away in the US. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(11):1105–1106. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman R.A. Comparison of driving times to opioid treatment programs and pharmacies in the US. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(11):1–9. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse S.C., Karem P., Shifflett K., Vegi L., Ravi K., Brooks M. Evaluating barriers to adopting telemedicine worldwide: A systematic review. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2018;24(1):4–12. doi: 10.1177/1357633X16674087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong M.W. Center for Connected Health Policy. 2020. State telehealth laws & reimbursement policies.https://www.cchpca.org/telehealth-policy/state-telehealth-laws-and-reimbursement-policies-report Retrieved December 22, 2020, from. [Google Scholar]

- Lin L.A., Fernandez A.C., Bonar E.E. Telehealth for substance-using populations in the age of Coronavirus Disease 2019: Recommendations to enhance adoption. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(12):1209–1210. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long K. States rapidly build their telehealth capacity to deliver opioid use disorder treatment. 2020, April 13. https://nashp.org/states-rapidly-build-their-telehealth-capacity-to-deliver-opioid-use-disorder-treatment/

- McLean K., Kavanaugh P.R. “They’re making it so hard for people to get help:” Motivations for non-prescribed buprenorphine use in a time of treatment expansion. The International Journal on Drug Policy. 2019;71:118–124. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran M. AMA house calls for continued flexibility of telehealth regulations beyond the pandemic. Psychiatric News. 2020 doi: 10.1176/appi.pn.2020.12b12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- New Jersey Division of Consumer Affairs (NJDCA) New Jersey Department of Law & Safety; Office of the Attorney General: 2020, July 15. Temporary certification of alcohol and drug counselor – Interns.https://www.njconsumeraffairs.gov/COVID19/Pages/Temporary-Certification-of-Alcohol-and-Drug-Counselor-Interns.aspx [Google Scholar]

- New Jersey Division of Mental Health and Addiction Services (NJDMHAS). (2020, March 17). Opioid treatment program guidance. New Jersey Department of Human Services. https://www.state.nj.us/humanservices/dmhas/information/stakeholder/.

- Nguyen T.D., Gupta S., Ziedan E., Simon K.I., Alexander G.C., Saloner B., Stein B.D. Assessment of filled buprenorphine prescriptions for opioid use disorder during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2021;181(4):562–565. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.7497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes E.V., Levin F.R., Reilly M.P., El-Bassel N. Medication treatment for opioid use disorder in the age of COVID-19: Can new regulations modify the opioid cascade? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2020;122:108196. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas L.A., Horwitz S.M., Green C.A., Wisdom J.P., Duan N., Hoagwood K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2015;42(5):533–544. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panchal N., Kamal R., Orgera K., Cox C., Garfield R., Munana C., Chidambaram P. The implications of COVID-19 for mental health and substance use. 2020. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/the-implications-of-covid-19-for-mental-health-and-substance-use/ Kaiser Family Foundation.

- Patton M.Q. 4th ed. Sage Publications; 2014. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. [Google Scholar]

- Samet J.H., Botticelli M., Bharel M. Methadone in primary care — One small step for congress, one giant leap for addiction treatment. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018;379(1):7–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1803982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samples H., Williams A.R., Olfson M., Crystal S. Risk factors for discontinuation of buprenorphine treatment for opioid use disorders in a multi-state sample of Medicaid enrollees. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2018;95:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2018.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte B., Schmidt C.S., Strada L., Götzke C., Hiller P., Fischer B., Reimer J. Non-prescribed use of opioid substitution medication: Patterns and trends in sub-populations of opioid users in Germany. The International Journal on Drug Policy. 2016;29:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavova S., Rock P., Bush HM., Quesinberry D., Walsh S.L. Signal of increased opioid overdose during COVID-19 from emergency medical services data. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;214 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofuoglu M., DeVito E.E., Carroll K.M. Pharmacological and behavioral treatment of opioid use disorder. Psychiatric Research and Clinical Practice. 2019;1(1):4–15. doi: 10.1176/appi.prcp.20180006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Opioid treatment program (OTP) guidance. 2020, March 19. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/otp-guidance-20200316.pdf U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) FAQs: Provision of methadone and buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid use disorder in the COVID-19 emergency. 2020, April 21. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/faqs-for-oud-prescribing-and-dispensing.pdf U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- Taylor B., Henshall C., Kenyon S., Litchfield I., Greenfield S. Can rapid approaches to qualitative analysis deliver timely, valid findings to clinical leaders? A mixed methods study comparing rapid and thematic analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton J.D., Varisco T.J., Bapat S.S., Downs C.G., Shen C. Impact of COVID-19 related policy changes on buprenorphine dispensing in Texas. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2020;14(6):e372–e374. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uscher-Pines L., Sousa J., Raja P., Mehrotra A., Barnett M., Huskamp H.A. Treatment of opioid use disorder during COVID-19: Experiences of clinicians transitioning to telemedicine. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2020;118:108124. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams A.R., Nunes E.V., Bisaga A., Levin F.R., Olfson M. Development of a cascade of care for responding to the opioid epidemic. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2019;45(1):1–10. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2018.1546862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y.T., Weintraub E., Haffajee R.L. Telemedicine’s role in addressing the opioid epidemic. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2018;93(9):1177–1180. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material