ABSTRACT

Dihydrouridine (D) is a tRNA-modified base conserved throughout all kingdoms of life and assuming an important structural role. The conserved dihydrouridine synthases (Dus) carries out D-synthesis. DusA, DusB and DusC are bacterial members, and their substrate specificity has been determined in Escherichia coli. DusA synthesizes D20/D20a while DusB and DusC are responsible for the synthesis of D17 and D16, respectively. Here, we characterize the function of the unique dus gene encoding a DusB detected in Mollicutes, which are bacteria that evolved from a common Firmicute ancestor via massive genome reduction. Using in vitro activity tests as well as in vivo E. coli complementation assays with the enzyme from Mycoplasma capricolum (DusBMCap), a model organism for the study of these parasitic bacteria, we show that, as expected for a DusB homolog, DusBMCap modifies U17 to D17 but also synthetizes D20/D20a combining therefore both E. coli DusA and DusB activities. Hence, this is the first case of a Dus enzyme able to modify up to three different sites as well as the first example of a tRNA-modifying enzyme that can modify bases present on the two opposite sides of an RNA-loop structure. Comparative analysis of the distribution of DusB homologs in Firmicutes revealed the existence of three DusB subgroups namely DusB1, DusB2 and DusB3. The first two subgroups were likely present in the Firmicute ancestor, and Mollicutes have retained DusB1 and lost DusB2. Altogether, our results suggest that the multisite specificity of the M. capricolum DusB enzyme could be an ancestral property.

KEYWORDS: tRNA, post-transcriptional modification, dihydrouridine, multisite-specificity, mollicutes

Introduction

Dihydrouridine (D) is one of the most abundant post-transcriptional modified nucleosides of the transcriptome. It is found mainly in transfer RNA (tRNA) and occasionally in ribosomal RNAs (rRNA) [1]. D is produced via the reduction of uridine’s C5 = C6 double bond to give a non-aromatic base. This loss of aromaticity, which is a unique feature among nucleic acids, disrupts the base planarity and consequently prevents D from participating in stacking interactions [2]. The physiological role of D is yet to be fully understood, although several convergent observations suggest its importance for structuring RNAs. Indeed, and as shown by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, the presence of D promotes the local flexibility and dynamics of RNA backbone [3]. While unmodified oligonucleotide can adopt several undefined conformations that interconvert in solution, it was shown that the presence of D triggers the folding of oligonucleotides into a specific hairpin with a stable stem and flexible loop region [4]. This may explain why D occurs mainly in single stranded loops and in regions of RNA that need flexibility such as the sensitive elbow region of tRNA formed by the association of the D- and TpsiC-loops that involves important tertiary interactions required to maintain the peculiar L-shaped structure of tRNA [5]. Other evidence in favour of a structural role lies in the observation that the highest D-levels are found in tRNAs from psychrophilic bacteria while the lowest D-levels are found in tRNAs from thermophiles, suggesting that these psychrophilic bacteria make use of D as a strategy to adapt their nucleic acid molecules for low temperatures [6]. In addition, tRNAs lacking D along with other modifications are shown to undergo rapid degradation by specific RNAse [7], probably due to a defect in conformational flexibility. This could perhaps explain how cancer cells could prevent tRNA turnover by significantly increasing D-level in tRNAs [8,9] and consequently promote cellular growth, even if this hypothesis remains to be validated experimentally.

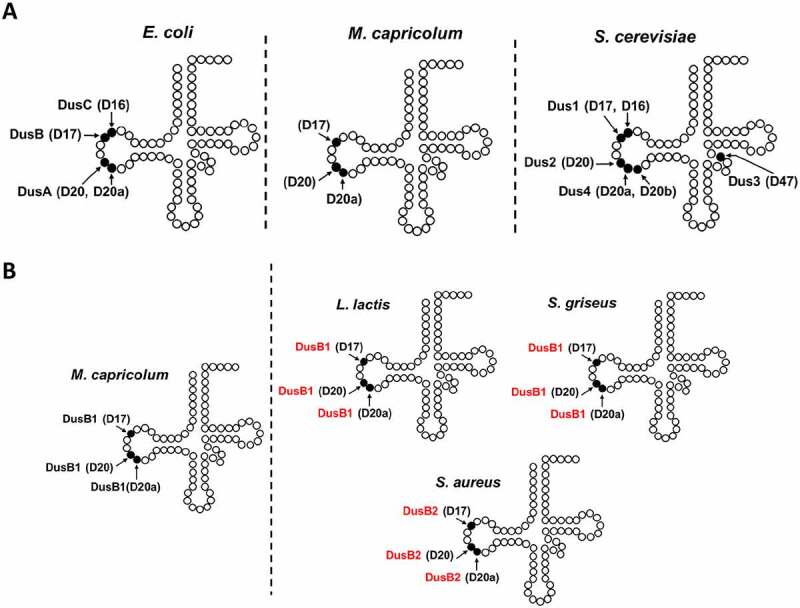

D modifications are not abundant in rRNAs. So far, D has been observed at a single location, 2449, in the central loop of domain V in Escherichia coli 23 S ribosomal RNA [10], and at two positions, 2449 and 2500, in 23S ribosomal RNA of Clostridium sporogenes [11]. In this last case, however, D2449 was found to be methylated at the N5 atom to give m5D2449. In contrast, D is often found at multiple sites in tRNAs of bacteria and eukaryotes and its abundance varies both with the organism and the type of tRNA [1]. For instance, there are up to five positions where D can be found in prokaryotes, most frequently at positions 16, 17, 20 and 20a, all localized in the ‘D-loop’, and at position 47 in the variable loop (V-loop) (Fig. 1A, left). Note that the D47 position has been so far observed only in one tRNA of Bacillus subtilis, the [12]. In eukaryotes, D is observed in no less than six sites, five of which are in the D-loop (D16, D17, D20, D20a and D20b) and one is in the variable loop (D47) (Fig. 1A, middle).

Figure 1.

Location of D-sites in tRNA, site specificity of the known Dus enzymes and predicted site specificity of DusB corresponding enzymes in Firmicutes. (A) Schematic representation of the secondary structure of tRNA, showing the location of D residues and the corresponding Dus enzyme responsible for their synthesis in E. coli, eukaryotes and Mollicutes. (B) The presence of three D modifications in each gram+ bacteria presented are obtained by analysis of the tRNA sequences from Modomics. The specificity of DusB1 of Mycoplama capricolum has been validated here, experimentally. In red is indicated the predicted site specificity of the DusB homologue found in Lactococcus lactis, Streptomyces griseus and Staphylococcus aureus.

D residues are introduced in tRNAs by a set of conserved flavoenzymes, the dihydrouridine synthases (Dus), which are members of the Cluster of Orthologous Group family COG0042 annotated in protein sequence databases as ‘predicted TIM-barrel enzymes, possibly dehydrogenases, nifR3 family’ [13,14]. Based on phylogenetic studies, this family of enzymes can be subdivided into eight subfamilies, namely DusA, DusB, DusC, Dus1, Dus2, Dus3, Dus4 and archaeal Dus [15]. The first three enzymes are found in bacteria while Dus1 to Dus4 are eukaryotic enzymes, the last one is the only Dus member observed in archaea. To date, three-dimensional structures, obtained by X-ray crystallography, are available for DusA from Thermus thermophilus [16], DusB [17] and DusC [18] from Escherichia coli and human Dus2 [19–21]. These structures have confirmed the common domain architecture of Dus enzymes consisting of an N-terminal domain adopting a TIM-BARREL fold wherein the binding site of the FMN redox coenzyme lies in its centre, and a C-terminal helical domain formed by 4-helix bundle, which is dedicated to tRNA recognition [16,18]. Apart from these two strictly conserved protein domains, there are additional domains that are exclusively observed among certain members of eukaryotic Dus [15,22,23].

The substrate specificity of Dus has been so far studied in three model organisms: E. coli [13,17] and Thermus thermophilus for prokaryotes [16,24], and Saccharomyces cerevisiae for eukaryotes [14]. These studies reveal that Dus can usually modify one or two positions in a tRNA substrate (Fig. 1A). Indeed, DusA, Dus1 and Dus4 are dual-site enzymes catalysing the formation of D20/D20a, D16/D17 and D20a/D20b, respectively. In contrast, DusB, DusC, Dus2 and Dus3 can only modify a single position and synthesize D17, D16, D20 and D47, respectively. The phylogenetic distribution of Dus family subgroups is complex, particularly in bacteria. However, as DusB is present in almost all bacteria [15], a model where DusB is the bacterial ancestor, and DusA and DusC are the products of DusB duplication events that took place shortly after the divergence of the main Proteobacteria groups has been proposed [15]. In eukaryotes, Dus3 has been proposed to be the ancestral enzyme from which the three others derived starting with Dus2, then Dus1 and lastly Dus4. From an evolutionary perspective, the dual-site specificity of Dus might thus be considered as a functional feature that evolved recently. Here we tested this hypothesis by experimentally characterizing the unique Dus family member found in Mollicutes, annotated as a DusB, using Mycoplasma capricolum as a model organism.

Mollicutes are parasitic bacteria that have evolved from a common Firmicute ancestor via massive genome reduction. Quite remarkably, we show here that DusBMCap is the only enzyme responsible for the synthesis of D17, D20 and D20a in tRNAs, whereas a set of two enzymes (DusA and DusB) are usually required to introduce these three modifications in proteobacteria. Our results are consistent with the idea that multi-site specificity is probably not a recently emerged enzymatic property in RNA biology.

Materials and methods

Cloning of the putative DusB MCap

We obtained a commercially supplied synthetic plasmid of DusB from Mycoplasma capricolum (pEX-DusBMCap ampicillin-resistant) from Eurofins (Fig. S1). We used this plasmid to amplify by PCR and clone into pET15b the gene of DusB Mycoplasma capricolum containing a sequence encoding for 6-histidine tag placed at the N-terminal region of the protein. The PCR fragment was amplified with these primers (FW-ctggtgccgcgcggca gccatatgATGAAAATTGGCAATATCCAG; REV-gttagcagccggatcctcgagcatatgTTATTCTTCGCGATATTCTTTG) and purified with QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen), before cloning with SLIC cloning method into pET15b previously linearized with NdeI and gel purified with QIAquick gel purification kit (Qiagen). Chemically competent DH5α cells were transformed with the plasmid and gene integrity was verified by DNA sequencing (Eurofins).

Expression and purification of DusB from mycoplasma capricolum

Chemically competent E. coli BL21DE3 star cells transformed with pET15b-DusBMCap plasmid were grown in LB (Luria-Bertani) medium supplemented with ampicillin (100 µg mL−1) at 37°C, until the optical density at 600 nm reached 1.8. Protein synthesis was induced by addition of isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside to a final concentration of 0.5 mM. Cells were grown overnight at 16°C, collected by centrifugation (6300g at 4°C for 15 min) and stored at −80°C until use. Cells were re-suspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8 containing 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM β-mercapto-ethanol, 5 mM imidazole and discontinuously sonicated for 15 min in water ice batch. Cellular extracts were centrifuged for 1 h at 148.000 g, which yielded a soluble fraction of DusBMCap. The soluble fraction was loaded on a HiTrap crude FF column (GE Heathcare) previously equilibrated with 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 300 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole, 5 mM β-mercapto-ethanol (Buffer A). After extensive wash with 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 300 mM NaCl, 30 mM imidazole, 5 mM β-mercapto-ethanol, the protein was eluted with linear gradient of buffer A supplemented with 500 mM imidazole. Fractions containing DusBMCap were pooled, concentrated by ultrafiltration and loaded on Superdex S200 16–600 equilibrated in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 250 mM NaCl, 5 mM β-mercapto-ethanol. Only fractions corresponding to the monomer were combined and concentrated giving a pure and homogenous protein. Finally, protein was concentrated to 42 mg/ml, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use. Protein concentrations were determined by Bradford assay (Biorad) with BSA used as a standard.

NAD(P)H oxidase activity

The ability of DusBMCap to oxidize NADH and/or NADPH under steady state conditions was determined in the presence of air, as final electron acceptor, in 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl and 10% glycerol. Assays were performed using 2 µM protein in the presence of various concentrations of NAD(P)H ranging from 50 to 500 µM. The amount of NAD(P)H oxidized was monitored by following the decrease of absorbance at 343 nm (ε343 = 6.21 mM−1 cm−1). The initial rate versus NAD(P)H concentration was analysed according to Michaelis-Menten formalism.

Activity assay and dihydrouridine quantification

In vitro activity was assayed for 1 hour at 30°C in 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM ammonium acetate, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 2 mM MgCl2, 10% v/v glycerol under anaerobic conditions. Bulk tRNAs (100 µM) issued from a BW25113, ΔdusA::kan, ΔdusB::kan or ΔdusC::kan E. coli strain were incubated with 10 µM of protein in a total volume of 50 µL and reaction was started with addition of 1 mM NADPH. Quenching was performed by adding 50 µL of acidic phenol (Sigma Aldrich) followed by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 10 minutes. tRNAs in the aqueous phase were ethanol precipitated and further purified using a MicroSpin G-25 column (GE-healthcare). Dihydrouridine quantification was carried out by means of a colorimetric method as followed. Briefly, samples were incubated at 40°C for 30 minutes after addition of 5 µL of 1 M KOH. The solutions were neutralized with 25 µL of 96% H2SO4 followed by 25 µL of a 3% solution 2,3-butanedione monoxime (Sigma Aldrich) and 25 µL of a saturated solution in N-Phenyl-p-phenylenediamine (Sigma Aldrich). Samples were then heated at 95°C for 10 minutes and cooled to 55°C. Following addition of 50 µL of 1 mM FeCl3, a violet-red colouration appeared allowing quantification via absorption at 550 nm. Concentration of D in tRNA was determined by using a standard curve obtained with variable amounts of dihydrouracil.

MS analysis of purified E. coli tRNAs

Bulk tRNA was extracted from E. coli strains BW25113 (F−, ∆(araD-araB)567, ∆lacZ4787::rrnB-3, λ−, rph-1, ∆(rhaD-rhaB)568, hsdR514) and its derivative ΔdusA::kan, ΔdusB ΔdusC. This strain was obtained following a procedure described elsewhere [25]. Cells were transformed with empty pBAD24 or a pBAD24 derivative (pBAD24::MCAP0837) containing the MCAP0837 (DusBMCap) cloned between the NcoI and HindIII sites and expressed under the control of an arabinose inducible promoter. Cells were grown in 500 ml of LB supplemented with ampicillin (100 µg.mL−1) and arabinose (0.02%) to an OD600 of 0.8 and treated as previously described [21]. Purification of , and was made with 5ʹ biotinylated complementary oligonucleotide (TGGTGCATCCGGGAGGATTCGAACCTCCGACCG, TGGTAGGCCTGAGTGGACTTGAACCACCG and GGACTTGAACCCCCACGTCCGTAAGGACACTAACACCTGAAGCTAGCG, respectively) coupled to Streptavidin Magnesphere Paramagnetic particles (Promega). Annealing of specific tRNA was made in 1xTMA buffer (Tris-HCl pH 7.5 10 mM, EDTA 0.1 mM, tetramethylammonium chloride 0.9 M) by heating the mixture at 95°C for 3 minutes and 60°C for 30 minutes. Paramagnetic particles were then washed three times with 1xTMA buffer and specific tRNA was recovered by heating the final suspension at 95°C for 3 minutes. Specific tRNAs were desalted and concentrated four times to 50 μl in Vivaspin 500 devices (Sartorius; 3,000 MWCO) using 100 mM ammonium acetate (pH 5.3) as a final buffer.

For mass spectrometry analysis, about 50 μg of tRNAs were digested with 10 μg of RNAse A (Euromedex), which cleaves after C and U and generates 3′-phosphate nucleosides, in a final volume of 10 μl at 37°C for 4 h. One microlitre of digest was mixed with 9 μl HPA (40 mg/ml in water: acetonitrile 50:50) and 1 μl of the mixture was spotted on the MALDI plate and air-dried (‘dried droplet’ method) as described previously. MALDI-TOF MS analyses were performed directly on the digestion products using an UltrafleXtreme spectrometer (Bruker Daltonique, France). Acquisitions were performed in positive ion mode. An identical strategy was applied for RNase T1 digests (cleavage after G generating 3ʹ-phosphate nucleosides).

Bioinformatic analyses

The resources of Uniprot [26] and NCBI [27] were routinely used to extract protein and gene sequences. Multiple sequence alignments were generated using Clustal Omega (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/). Multiple tools from the PATRIC database [28] were used to extract and manipulate protein sequences. A set of 91 Firmicute genomes containing reference and representative Firmicutes genomes with the addition of a few Mycoplasma genomes was selected for further analysis (see complete list Table S1). A taxonomic phylogenetic tree was generated using the PATRIC tree tool after adding seven non-Firmicutes genomes serving as outgroup (Table S1). Proteomes from these 98 organisms were searched using the PATRIC blast tool using default parameters and DusBMcap (MCAP_0837). This led to the identification of 143 DusB family proteins with 235 of these in Firmicutes (Supplemental Data sequences) covered by three global PATRIC families: PGF_00912265 corresponding to the DusB1/BSU00810 subgroup; PGF_03473104 corresponding to the DusB2/BSU08030 subgroup; PGF_03696321 corresponding to the DusB3/BT_3326 subgroup. A sequence similarity network (SSN) was generated with this set of DusB proteins from Firmicutes using Enzyme Function Initiative suite of webtools [29,30]. SSNs were visualized using Cytoscape [31]. The parameters used for the generation of the Firmicutes DusB SSNs were as follows: the input method ‘FASTA’ (option C) with an alignment score threshold of 40. ITol was used to generated the phylogenetic distribution graph [32].

Results

Biochemical characterization DusBMCap confirms it is a flavoprotein

A gene sequence (NC_007633.1:c969041-968,067) from Mycoplasma capricolum subsp. capricolum ATCC 27,343 (Fig. S1), also known as MCAP_RS04190, MCAP_0837, is annotated as a putative tRNA dihydrouridine synthase DusB (NCBI Reference Sequence: WP_036431687.1) in NCBI. The corresponding protein is composed of 324 amino-acids and presents 45%, 37%, 27%, 24% and 19% of sequence identity with B. subtilis DusB1 (BSU00810), E. coli DusB (UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot: P0ABT5.1), E. coli DusC (UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot: P33371.1), B. subtilis DusB2 (BSU08030) and E. coli DusA (UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot: P32695.4), respectively (see sequence alignment Fig S2).

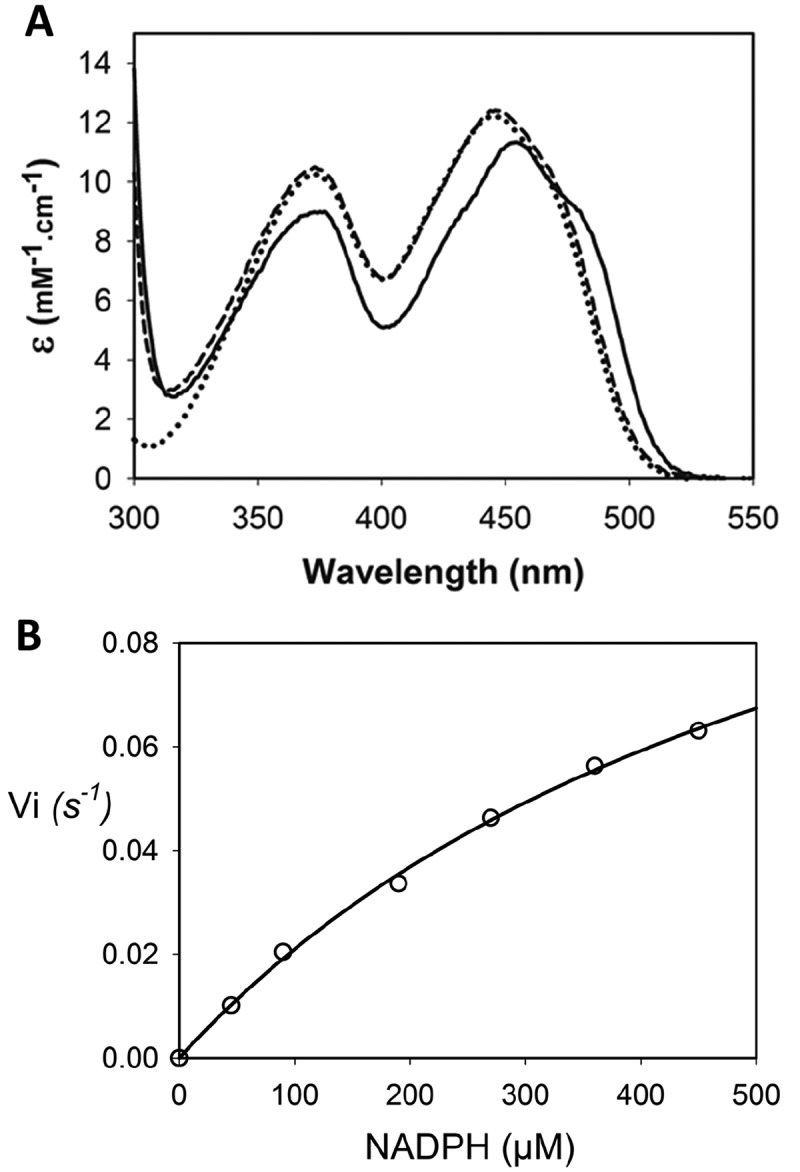

To verify if this gene encodes for a dihydrouridine synthase, we cloned it into a pET15b plasmid, overexpressed in E. coli BL21DE3 star cells and subsequently purified the recombinant protein. The SDS-PAGE gel shows that the overexpressed recombinant DusBMCap is present in the soluble fraction of E. coli and is readily purified to homogeneity (Fig. S3). Analytical gel filtration profile reveals that the protein elutes at an elution volume of 14.9 mL corresponding to a molecular weight of 32 kDa based on the standards calibration curve (Fig. S4). This result indicates that DusBMCap forms a monomer in solution like all other Dus proteins studied to date. The purified protein harbours a yellowish colour due to the presence of the flavin prosthetic group. Indeed, the absorbance spectrum of DusBMCap shows a typical spectrum of oxidized flavin as indicated by two major bands (Fig. 2A). The first absorption band is broad and localized between 370 and 378 nm while the second one is more structured with a peak at 454 nm characterized by an extinction coefficient of 11.3 mM−1 cm−1 along with the presence of a hyper-structure around 480 nm suggesting that the flavin is well anchored to its apoprotein. This is further corroborated by the fact that the addition of 0.1% SDS, an amount sufficient to denature proteins, causes significant changes in the absorbance spectrum, which is identical to that of the free FMN in solution, therefore suggesting that flavin is not covalently bound and readily dissociates from the holoprotein upon denaturation. Taken together, these results indicate that DusBMCap is a flavoprotein.

Figure 2.

Absorbance spectrum and NADPH oxidase activity of DusBMCap . (A) In solid line (▬) is the spectrum of oxidized DusBMcap alone while the spectrum in dashed line (–) is upon denaturing condition in the presence of 0.1% SDS. Spectrum of a solution of free FMN is in dotted line (•••). (B) Steady state for the NADPH oxidase activity of DusBMcap. The open circles are the raw data while the solid line is the fit with a Michaelis Menten equation

Both NADH and NADPH reduced the DusBMCap bound flavin

As in most flavoenzymes, flavin is employed as a redox catalyst. In the case of the enzymatic reaction catalysed by Dus enzymes, FMN is expected to be first reduced by NAD(P)H to the flavin hydroquinone, FMNH−, and then oxidized by the tRNA to produce D modification according to the following reactional equations: (E1) NAD(P)H + FMN ⇔ NAD(P)+ + FMNH− and (E2) FMNH− + U-tRNA + H+ ⇔ FMN + D-tRNA [33] (see Fig. S4 for details regarding the chemical mechanism). In order to determine if the flavin of DusBMCap is reducible, we first checked the effect of the artificial electron donor, dithionite, on the absorbance spectrum of the protein (Fig. S6, upper panel). Upon addition of one molar equivalent of dithionite, the spectrum of oxidized FMN changed instantly with a complete disappearance of the band at 454 nm, giving rise to a new spectrum characterized by a broad band between 310 and 350 nm typical of that of a flavin hydroquinone species. Hence, FMN of DusBMCap is redox responsive and is able to form the redox active intermediate, FMNH−. We then verified if NAD(P)H is able to reduce DusBMCap. The addition of one molar equivalent of NADH led to a slow decrease of the protein spectrum consistent with a slow reduction of FMN (Fig. S6, middle panel). For instance, after 30-minute incubation time, only 9% of FMN was reduced. In drastic contrast, the reduction by NADPH was more efficient since 38% and 60% of the FMN-content were reduced in 10 and 30 minutes of reaction, respectively (Fig. S6, lower panel). On the other hand, when the concentration of NADH or NADPH was increased to 10 molar equivalents, then full FMN reduction was achieved in less than 10 minutes by the two reducing agents tested. These results clearly demonstrate that the two biological cofactors, NADH and NADPH, can reduce the FMN of DusBMCap but NADPH is the most effective one.

Analysis of DusBMCap NAD(P)H oxidase activity confirms a preference for NADPH

Oxidation of NADH or NADPH by air under steady state conditions is used here to further investigate their reactivity with DusBMCap. Fig. 2B shows that DusBMCap is, as expected, able to catalyse NADPH oxidation. The determined kcat and KM for this reaction are 0.1 ± 0.01 s−1 and 620 ± 90 µM, respectively. Unfortunately, we were not able to obtain any accurate values for the NADH oxidation due to a very low activity. These results are consistent with the reduction experiments and confirmed that DusBMCap exhibits a clear preference for NADPH.

DusBMCap can catalyse the formation of dihydrouridine in tRNA in vitro

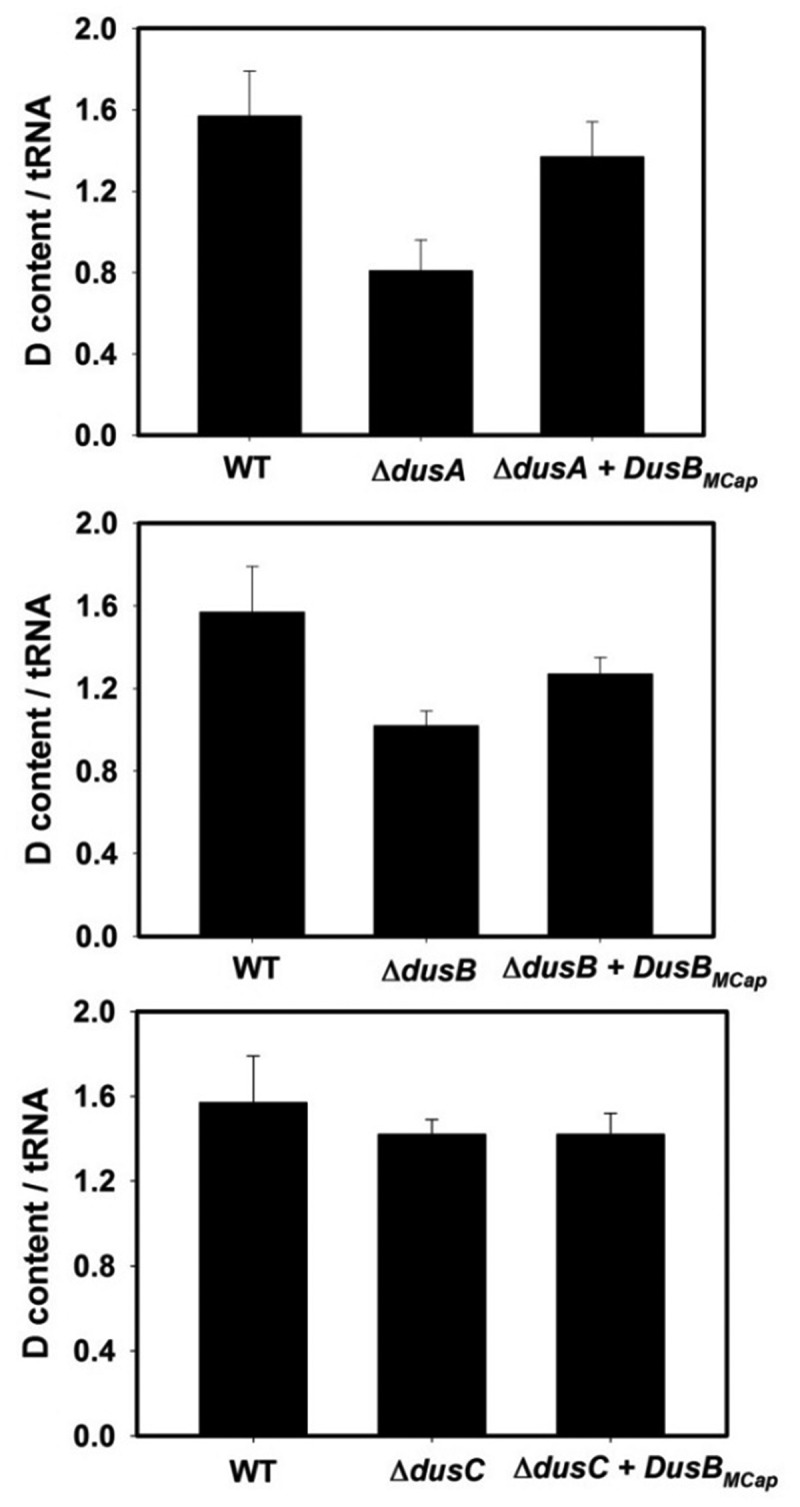

The ability of DusBMCap to catalyse the formation of D was then assayed in vitro using as substrate, E. coli bulk tRNAs prepared from mutant strains in which either dusA, dusB or dusC had been deleted (Fig. 3). The bulk tRNAs from wild type strain contains ~1.5 D per tRNA while this content is 0.6, 0.9 and 1.3 in the single dusA, dusB and dusC mutants, respectively. Incubation of DusBMCap with this bulk tRNAs from the ΔdusA strain increased the D content to 1.3 while this content was 1.2 in the presence of bulk tRNAs from the ΔdusB strain. No visible variation of the D content was observed with bulk tRNAs from the ΔdusC strain. These results suggest that DusBMCap is able of catalysing D20 and/or D20a and D17 but it is not able to synthetize D16.

Figure 3.

In vitro dihydrouridine synthase activity of DusBMCap. Average of D/tRNA value of E. coli bulk tRNA in the presence of DusBMCap + NADPH incubated for 1 h at 30°C under anaerobic conditions and determined by the colorimetric assay described in the material and methods. A standard curve obtained with variable amounts of dihydrouracil was used to determine the concentration of D in tRNA. The error bars are calculated from five different sets of experiments. The upper panel shows the D-content of bulk E. coli tRNAs from (I) wild-type strain, (ii) ΔdusA strain, (ii) ΔdusA in the presence of recombinant DusBMcap and NADPH. The middle panel shows the D-content of bulk E. coli tRNAs from (i) wild-type strain, (ii) ΔdusB strain, (ii) ΔdusB in the presence of recombinant DusBMcap and NADPH. The lower panel is the D-content in bulk E. coli tRNAs from (i) wild-type strain, (ii) ΔdusC strain, (ii) ΔdusC in the presence of recombinant DusBMcap and NADPH

E. coli complementation studies combined with mass spectrometry analysis of tRNAs confirm that DusBMCap can introduce D residues at positions 17, 20 and 20a

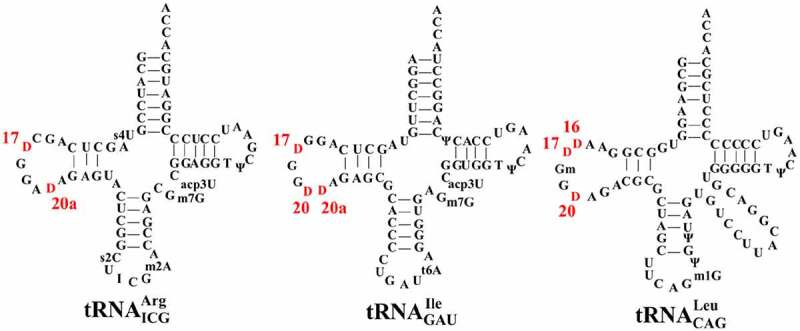

Genetic manipulations of Mollicutes are known to be intractable due to difficulties to culture these organisms, which renders impossible to determine the substrate site-specificity of DusBMCap in vivo. To circumvent this technical obstacle and determine the enzymatic property of DusBMCap, we opted for heterologous complementation assays of the triple E. coli dus mutants, ΔdusABC, with pBAD24::MCAP0837 expressing DusBMcap combined with analysis of tRNAs by MALDI-TOF after digestion with either RNAse T1 or A. Three tRNAs, namely , and , were chosen to identify the D sites modified by DusBMCap (Fig. 4 & Fig. S7).

Figure 4.

Secondary cloverleaf structure and sequence of E. coli , and . The positions of each D in the D-loop region are labelled in red

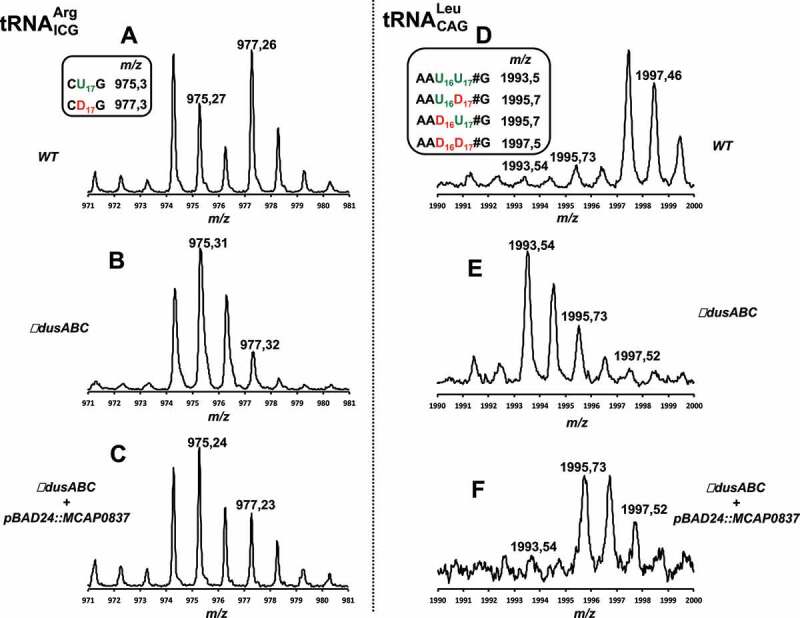

D17 formation was assessed in and via analysis of the MS relative isotope patterns of derived oligonucleotides after RNAse T1 treatment. Comparative analysis between the MS spectra of wild type and ΔdusABC tRNAs enabled us to identify four fragments that could be used as specific probes to unambiguously detect D17, namely RNAse T1 fragments CU17G (m/z 975.3) and CD17G (m/z 977.3) (Fig. 5A &B) and RNAse T1 AAU16U17GmG (m/z 1993.5) and AAU16D17GmG (m/z 1995.5) (Fig. 5D &E). While the intensity of peak m/z 975.3 (CU17G) is lower than that of m/z 977.3 (CD17G) in the wild type, the absence of D17 induce an inversion of intensity between those two peaks. In addition, the presence of D17 provokes the disappearance of m/z 1993.5 (AAU16U17GmG) and an increase in intensity of m/z 1995.5 (AAU16D17GmG). For tRNAs isolated from the ΔdusABC E. coli strain (BW25113 ∆dusA::kan, ∆dusB, ∆dusC) transformed with the pBAD24 derivative expressing DusBMCap (pBAD24::MCAP0837) the MS spectra show: (i) an increase of m/z 977.3 (, CD17G) compared to the ΔdusABC mutant, even though an inversion with m/z 975.3 (, CU17G) was not reached; (ii) the absence of m/z 1993.5 (, AAU16U17GmG); and (iii) the presence of m/z 1995.5 (AAU16D17GmG) (Fig. 5C & F). Hence, these results indicate that, as expected, expression of the dusBMCap gene complements the deletion of the E. coli dusB gene albeit partially, probably because of the heterologous systems used in these experiments.

Figure 5.

MALDI-TOF analysis of position 17 in tRNAs from E. coli ∆dusABC complemented with DusBMCap. (A), (B) and (C) are the MS relative isotope patterns of derived oligonucleotides after RNAse T1 treatment of isolated from wild type, ΔdusABC and ΔdusABC + pBAD24::MCAP0837, respectively. (D), (E) and (F) are the MS relative isotope patterns of derived oligonucleotides after RNAse T1 treatment of isolated from wild type, ΔdusABC and ΔdusABC + pBAD24::MCAP0837, respectively. Summary of the tRNA-derived oligonucleotide fragments and their sizes (m/z) used for the identification of MCAP_0837 specificity are shown in the small boxes and are further detailed in Table S2

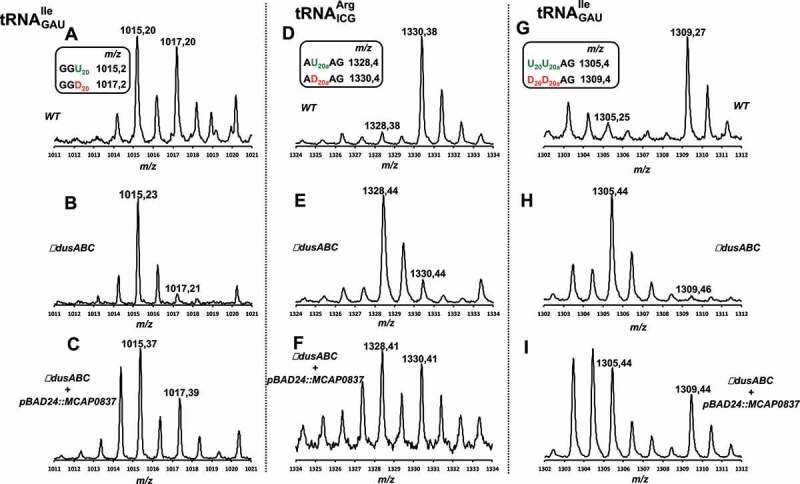

Using a similar approach, we then evaluated the ability of DusBMCap to insert D20 and D20a in and . The first tRNA allows the detection of D20a via its treatment with RNAse T1 while the second one allows detection of D20 after treatment with RNAse A or the double modification D20D20a after treatment RNAse T1. Apparition of m/z 1017 attributed to the RNAse A fragment GGD20 is a reliable indication for D20 formation (Fig. 6A & B) while the modification of position 20a can be observed by both the loss of RNAse T1 fragment AU20AG (m/z 1328) and the build-up of AD20AG (m/z 1330) (Fig. 6D & E). The dual D20D20a modification of , can be followed by the presence of RNAse T1 m/z 1309 (D20D20aAG) fragment and the loss of m/z 1305 (U20U20aAG) (Fig. 6G & H). Remarkably, even if these effects are not complete, the MS spectra clearly showed that DusBMCap can, like the E. coli DusA, modify both the positions 20 and 20a (Fig. 6C & F& I).

Figure 6.

MALDI-TOF analysis of positions 20 and 20a in tRNAs from E. coli ∆dusABC complemented with DusBMCap.(A), (B) and (C) are the MS relative isotope patterns of derived oligonucleotides after RNAse A treatment of isolated from wild type, ΔdusABC and ΔdusABC + pBAD24::MCAP0837, respectively. (D), (E) and (F) are the MS relative isotope patterns of derived oligonucleotides after RNAse T1 treatment of isolated from wild type, ΔdusABC and ΔdusABC + pBAD24::MCAP0837, respectively. (G), (H) and (I) are the MS relative isotope patterns of derived oligonucleotides after RNAse T1 treatment of isolated from wild type, ΔdusABC and ΔdusABC + pBAD24::MCAP0837, respectively. Summary of the tRNA-derived oligonucleotide fragments and their sizes (m/z) used for the identification of MCAP_0837 specificity are shown in the small boxes and are further detailed in Table S2

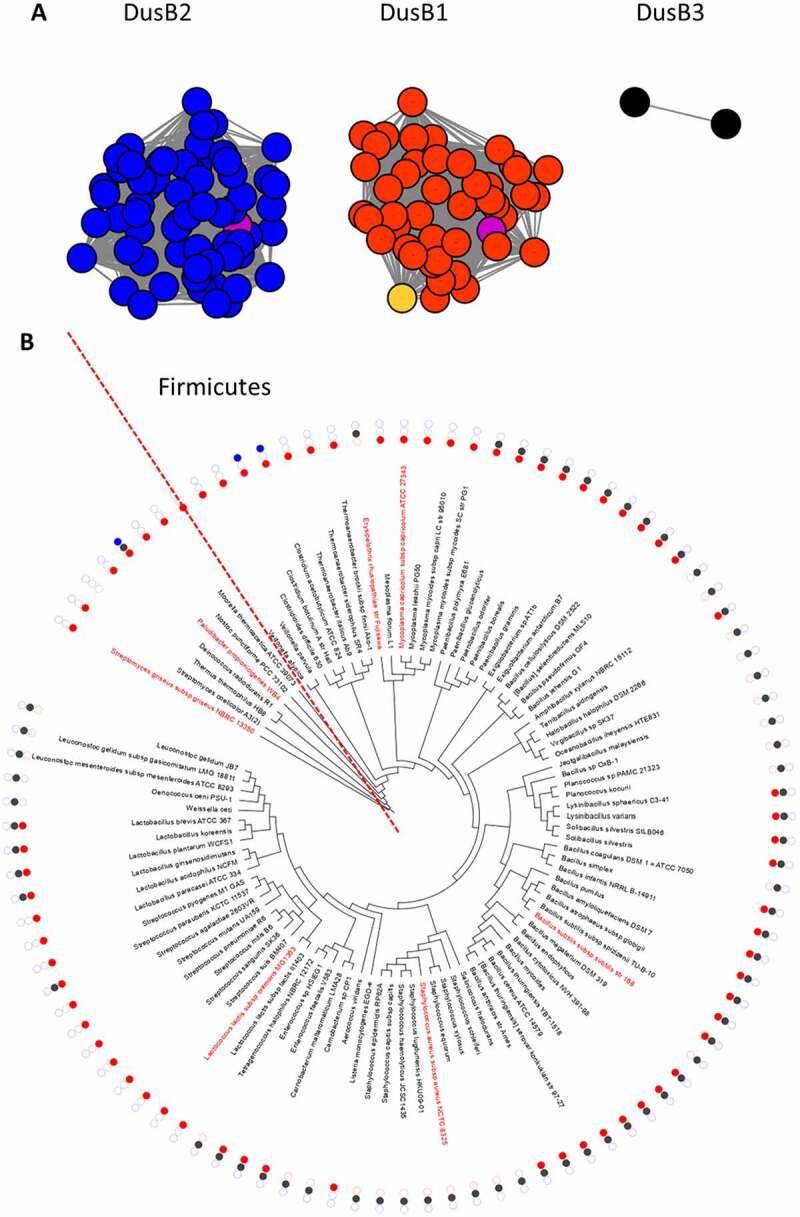

Analysis of the distribution of DusB family proteins in Firmicutes suggests the lost of an ancestral copy in Mollicutes

Previous analyses of the evolution of Dus enzymes in all kingdoms of life already established that DusB was certainly the ancestral bacterial enzyme and that Firmicutes lacked DusC and DusA homologs [15]. In addition, the same analysis detected two DusB duplications events in Firmicutes, one in B. subtilis and the other in Clostridium acetobutylicum without specifying if these were independent. As M. capricolum had not been included in this 2012 study and with so many additional genome sequences available, we decided to analyse the distribution of DusB family sequences in 95 Firmicutes as described in the methods section and summarized in Fig. 7. We recapitulated the results from a previous study by identifying three DusB subgroups (Fig. 7A). The first two DusB1 and DusB2 correspond to the paralogs found in B. subtilis. Nearly half of the Firmicutes analysed (40/95 or 42%) harboured both a DusB1 and DusB2 homolog, while 27% (26/95) harboured only a DusB1 homolog and 30% (29/95) harboured only a DusB2 homolog. DusBMcap like all other Dus from Mycoplasma is part of the DusB1 subgroup. The duplication of DusB1 and DusB2 must have occurred before the Mycoplasma split as the most closely related Firmicute in the tree Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae str. Fujisawa harbours only a DusB2 homolog suggesting the last common ancestor harboured both protein families and that DusB2 was lost in Mollicutes and DusB1 was lost in E. rhusiopathiae (Fig. 7B). The DusB1/DusB2 duplication must have occurred before the Firmicute radiation as DusB2 proteins are found in non-Firmicutes gram-positive such as Bacteroides. A third DusB subgroup, DusB3, is found mainly in Clostridia that also contains DusB1 homologs. This duplication could even have occurred before the Firmicute split as we identified a bacteroides, Paludibacter propionicigenes WB4, that containing members of the three subgroups (Fig. 7B), even if one cannot rule out horizontal gene transfer events at this stage without more extensive analyses. Finally, a recent duplication of DusB2 proteins occurred in a few sporadic genomes such as Staphylococcus aureus subsp. aureus COL that contains both a full length (SACOL0067) and a version truncated by half (SACOL0059).

Figure 7.

Analysis of DusB subgroups in Firmicutes. (A) Results from the sequence similarity network analysis of 143 DusB proteins from Firmicutes performed on the EFI website using an alignment score threshold of 40 and visualized with Cytoscape, the DusB1 proteins are in red, the DusB2 proteins in blue, the DusB3 proteins in black, the M. capricolum DusB1 protein is in orange, the B. subtilis DusB1 and DusB2 proteins are in magenta; (B) Phylogenetic distribution analysis of the three DusB subgroups. Organisms discussed in the text are in red, the dotted line delineates the Firmicute radiation

Discussion

Our biochemical results clearly show that DusBMCap retains the general features of Dus family members. It is a flavoenzyme that uses FMN as coenzyme and employs NADPH as a reducing agent to catalyse the reduction of uridine. However, the M. capricolum Dus enzyme have a low affinity for NADPH, which would explain why the reduction of the flavin by NADPH via a hydride transfer is slow, in contrast to other Dus enzymes 20, [21,33]. For comparison, the KM of DusBMCap for NADPH is more than 15 times greater than that for hDus2, the enzyme responsible for the synthesis of D20 in human.

Based on the in vitro activity tests in combination with E. coli complementation experiments, we have unambiguously established that DusB of mycoplasma is the enzyme responsible for the synthesis of dihydrouridines found at three different positions in the D-loop of tRNAs, namely D17, D20 and D20a. The availability of the 29 tRNAs sequences from M. capricolum allowed us to analyse the dihydrouridine distribution profile in this organism (Table S3). Interestingly, D20 is the most abundant as it is observed in 17 tRNAs, followed by D17 found in 13 tRNAs and finally by D20a present in 11 ARNts. tRNAs harbouring one unique D are the most prevalent with 17 tRNAs (eigth tRNAs contain a D20, five a D17 and four a D20a). Less tRNAs have more than one D residue with three tRNAs having both D17D20, one both D17D20a, two both D20D20a while four tRNAs harbour the three D17D20D20a modifications. This analysis suggests that the DusA-like activity (modification of position 20/20a) of DusBMCap must be greater than its DusB-like activity (modification of position 17). This is consistent with the observation that expressing the DusBMCap gene in the E. coli ΔdusABC strain led to a more efficient modification of position 20/20a than of the position 17. Although most tRNA modifying enzymes are mono-site specific, some are well known for their ability to display multi-site specificity and can insert identical modifications at contiguous and/or non-contiguous sites. For instance, Aquifex aeolicus Trm1, catalyzes the dimethylation of G26 and G27 in tRNA to m22G26 and m22G27 [34]. In E. coli, the pseudouridine synthase TruA synthesizes Ψ38, Ψ39 and Ψ40 in the anticodon stem loop of tRNAs [35]. The pseudouridine synthase Pus1p of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is able to modify positions U26, 27, 28, 34, 35, 36, 65 and 67 [36] and m5C found at four positions (34, 40, 48 and 49) in yeast tRNAs are inserted by the same SAM-dependent methyltransferase, Trm4 [37]. Pyrococcus abyssi TrmI methylates two adjacent adenines into m1A57m1A58 located in the TpsiC loop of tRNA [38,39] while Archaeosine tRNA-guanine transglycosylase from Thermoplasma acidophilum is responsible for the formation of both Archaeosine G(+)13 and G(+)15 modifications [40].

In the case of dihydrouridine synthases, DusA and Dus4 have been shown to modify up to two positions in tRNAs; however, DusBMCap represents the first case of a Dus enzyme capable of modifying three different sites, namely U17, U20 and U20a. More importantly, this is the first reported tRNA-modifying enzyme able to target nucleobase substrates placed at two spatially opposite sides of an RNA-loop. This implies that DusBMCap carries the tRNA binding mode of both DusA and DusB. The crystallographic structures of T. thermophilus DusA and E. coli DusC in complex with a tRNA as well as a structural model of E. coli DusB/tRNA complex have shed light on the exquisite substrate specificity of these RNA-modifying enzymes [16–18]. These structures show that despite an overall conservation of the Dus fold (a N-terminal TIM-Barrel catalytic domain followed by a C-terminal helical domain, HD), the Dus enzymes gain access to their respective uridine substrates by using drastically distinct tRNA orientations. These orientations are allowed by well distinct electrostatic potential surfaces resulting from patches of solvent exposed lysine and arginine residues specific to each paralog. Dus enzymes that modify uridines at positions 16 and 20 bind their tRNA substrates in completely different orientations where the binding modes of the two Dus subfamilies differ by a major (∼160°) rotation of the whole tRNA molecule. As far as position 17 is concerned, we previously showed that DusC-oriented tRNA is well adapted to the positive patches on the surface of DusB that appears complementary in shape and in charge to the tRNA [17]. In the absence of a DusBMCap three-dimensional structure, the mechanism underlying its functional multisite specificity remains difficult to establish. However, by combining the analysis of the D distribution in M. capricolum tRNA sequences with the dihydrouridine synthase activity assays showing that the insertion of one modification is not required for the insertion of the other, we expect that the DusA-like and DusB-like activities are independent. Consequently, DusBMCap would probably bind the tRNAs in two completely different orientations to gain access to U17 and U20/U20a without any preferential order. Such a scenario is preferred over the single-orientation binding accompanied by the partial melting of the tRNA observed with the archaeosine tRNA-guanine transglycosylase [41], wherein the enzyme disrupts the L-shaped tertiary structure of tRNA into a lambda form to access to G15 in the D-loop. Hence, obtaining the crystal structure of DusBMCap would definitely clarify this interesting issue.

Our phylogenetic analysis of Dus family proteins in Firmicutes allowed the identification of three DusB subgroups, namely DusB1, DusB2 and DusB3 (Fig. 7A). The distribution of these proteins shows that if many of these organisms (~ 40%) harbour both DusB1 and DusB2, the majority encode only a DusB1 or DusB2 (Fig. 7B). This suggests that these two Dus were present in the common ancestor of Firmicutes and that they are the product of an ancestral DusB duplication event. For instance, most of the Bacillus has retained both DusB1 and DusB2 whereas Mollicutes have conserved DusB1 and lost DusB2. It should be noted that the low abundance of DusB3 found mainly in Clostridiae suggests that this Dus homolog could have appeared more recently. Conversely, most of the Staphylococcus has retained DusB2 and lost DusB1.

One of the remarkable questions this work raises is: why during evolution these three DusB orthologues emerged among Firmicutes and, hence what is their exact function? We have unambiguously established that unlike the protobacteria, Mollicutes only use DusB1 to introduce the total D content in their tRNAs, namely, D17, 20 and 20a (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, the availability of the modification profiles for tRNAs in Modomics of two other gram-positive bacteria namely, Lactococcus lactis and Streptomyces griseus, showing the presence of D17, 20 and 20a as well as the fact that both organism present only a DusB1 also suggest that this DusB homologue introduces all D-residues in the tRNAs of these other Gram-positive bacteria (Fig. 1B). Therefore, this multisite-specificity is likely a general feature of DusB1.

Similarly, it can be hypothesized that DusB2 is probably like DusB1, a multisite specific enzyme, responsible for the synthesis of these three D in organisms harbouring these modifications and only a DusB2 homolog. This is the case of Staphylococcus aureus showing the presence of D17, D20 and D20a in its tRNA [42] and, (ii) a DusB2 (Fig. 1B). This hypothesis will of course require experimental validation.

Eventually, it remains to be understood why some organisms have kept two or even three of the DusB homologues and what their function is. The study of these Dus will be key for understanding the complex functional evolution of the Dus family and to propose a plausible evolutionary scenario of this family of enzymes. Nonetheless, DusB can be considered the oldest member of the Dus family because it is distributed throughout the whole bacteria taxa [15]. Although the specificity of DusB has been so far studied exclusively in E. coli, demonstrating its monospecific character [17], here, the establishment that DusB1 from M. capricolum, a monophyletic class that is derived from Firmicutes, is multisite specific suggests that this enzymatic property is likely a vestige of ancestral RNA biology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, the university Pierre et Marie Curie (Emergence Program), the French State Program ‘Investissements d’Avenir’ (Grants ANR-15-CE11-0004-01 to DH and Grants “LABEX DYNAMO”, ANR-11-LABX-0011 to MF and DH) as well as by National Institutes of Health (Grant R01 GM70641 to V dC-L).

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche [ANR-15-CE11-0004-01]; Agence Nationale de la Recherche [ANR-11-LABX-0011]; Foundation for the National Institutes of Health [GM70641].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

References

- [1].Boccaletto P, Machnicka MA, Purta E, et al. MODOMICS: a database of RNA modification pathways. 2017 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D303–D7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Suck D, Saenger W, Zechmeister K.. Conformation of the tRNA minor constituent dihydrouridine. FEBS Lett. 1971;12:257–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Dalluge JJ, Hashizume T, Sopchik AE, et al. Conformational flexibility in RNA: the role of dihydrouridine. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:1073–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Dyubankova N, Sochacka E, Kraszewska K, et al. Contribution of dihydrouridine in folding of the D-arm in tRNA. Org Biomol Chem. 2015;13:4960–4966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kim SH, Suddath FL, Quigley GJ, et al. Three-dimensional tertiary structure of yeast phenylalanine transfer RNA. Science. 1974;185:435–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Dalluge JJ, Hamamoto T, Horikoshi K, et al. Posttranscriptional modification of tRNA in psychrophilic bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1918–1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Alexandrov A, Chernyakov I, Gu W, et al. Rapid tRNA decay can result from lack of nonessential modifications. Mol Cell. 2006;21:87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kuchino Y, Borek E.. Tumour-specific phenylalanine tRNA contains two supernumerary methylated bases. Nature. 1978;271:126–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kato T, Daigo Y, Hayama S, et al. A novel human tRNA-dihydrouridine synthase involved in pulmonary carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5638–5646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].O’Connor M, Lee WM, Mankad A, et al. Mutagenesis of the peptidyltransferase center of 23S rRNA: the invariant U2449 is dispensable. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:710–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kirpekar F, Hansen LH, Mundus J, et al. Mapping of ribosomal 23S ribosomal RNA modifications in Clostridium sporogenes. RNA Biol. 2018;15:1060–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Yamada Y, Ishikura H. Nucleotide sequence of non-initiator methionine tRNA from Bacillus subtilis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980;8:4517–4520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bishop AC, Xu J, Johnson RC, et al. Identification of the tRNA-dihydrouridine synthase family. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:25090–25095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Xing F, Hiley SL, Hughes TR, et al. The specificities of four yeast dihydrouridine synthases for cytoplasmic tRNAs. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:17850–17860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kasprzak JM, Czerwoniec A, Bujnicki JM. Molecular evolution of dihydrouridine synthases. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13:153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Yu F, Tanaka Y, Yamashita K, et al. Molecular basis of dihydrouridine formation on tRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:19593–19598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Bou-Nader C, Montemont H, Guerineau V, et al. Unveiling structural and functional divergences of bacterial tRNA dihydrouridine synthases: perspectives on the evolution scenario. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:1386–1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Byrne RT, Jenkins HT, Peters DT, et al. Major reorientation of tRNA substrates defines specificity of dihydrouridine synthases. Proc Natl Sci USA. 2015; 112:6033–6037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Whelan F, Jenkins HT, Griffiths SC, et al. From bacterial to human dihydrouridine synthase: automated structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2015;71:1564–1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Bou-Nader C, Pecqueur L, Bregeon D, et al. An extended dsRBD is required for post-transcriptional modification in human tRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:9446–9456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bou-Nader C, Bregeon D, Pecqueur L, et al. Electrostatic potential in the tRNA binding evolution of dihydrouridine synthases. Biochemistry. 2018;57:5407–5414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Bou-Nader C, Barraud P, Pecqueur L, et al. Molecular basis for transfer RNA recognition by the double-stranded RNA-binding domain of human dihydrouridine synthase 2. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:3117–3126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Bou-Nader C, Pecqueur L, Barraud P, et al. Conformational stability adaptation of a double-stranded RNA-binding domain to transfer RNA ligand. Biochemistry. 2019;58:2463–2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kusuba H, Yoshida T, Iwasaki E, et al. In vitro dihydrouridine formation by tRNA dihydrouridine synthase from Thermus thermophilus, an extreme-thermophilic eubacterium. J Biochem. 2015;158:513–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6640–6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].The UniProt Consortium the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D158–D69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Agarwala R, Barrett T, Beck J. Database resources of the national center for biotechnology information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D8–D13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Davis JJ, Wattam AR, Aziz RK, et al. The PATRIC bioinformatics resource center: expanding data and analysis capabilities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:D606–D12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Gerlt JA, Bouvier JT, Davidson DB, et al. Enzyme function initiative-enzyme similarity tool (EFI-EST): a web tool for generating protein sequence similarity networks. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1854:1019–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Zallot R, Oberg NO, Gerlt JA. ‘Democratized’ genomic enzymology web tools for functional assignment. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2018;47:77–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL): an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:127–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Rider LW, Ottosen MB, Gattis SG, et al. Mechanism of dihydrouridine synthase 2 from yeast and the importance of modifications for efficient tRNA reduction. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:10324–10333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Awai T, Kimura S, Tomikawa C, et al. Aquifex aeolicus tRNA (N2,N2-guanine)-dimethyltransferase (Trm1) catalyzes transfer of methyl groups not only to guanine 26 but also to guanine 27 in tRNA. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:20467–20478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hur S, Stroud RM. How U38, 39, and 40 of many tRNAs become the targets for pseudouridylation by TruA. Mol Cell. 2007;26:189–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Motorin Y, Keith G, Simon C, et al. The yeast tRNA:pseudouridine synthase Pus1p displays a multisite substrate specificity. RNA. 1998;4:856–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Motorin Y, Grosjean H. Multisite-specific tRNA:m5C-methyltransferase (Trm4) in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: identification of the gene and substrate specificity of the enzyme. RNA. 1999;5:1105–1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Roovers M, Wouters J, Bujnicki JM, et al. A primordial RNA modification enzyme: the case of tRNA (m1A) methyltransferase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:465–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Hamdane D, Guelorget A, Guerineau V, et al. Dynamics of RNA modification by a multi-site-specific tRNA methyltransferase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:11697–11706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kawamura T, Hirata A, Ohno S, et al. Multisite-specific archaeosine tRNA-guanine transglycosylase (ArcTGT) from Thermoplasma acidophilum, a thermo-acidophilic archaeon. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:1894–1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Ishitani R, Nureki O, Nameki N, et al. Alternative tertiary structure of tRNA for recognition by a posttranscriptional modification enzyme. Cell. 2003;113:383–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Antoine L, Wolff P, Westhof E, et al. Mapping post-transcriptional modifications in Staphylococcus aureus tRNAs by nanoLC/MSMS. Biochimie. 2019;164:60–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.