Abstract

Background:

Asian healthcare professionals hold that patients’ families play an essential role in advance care planning.

Aim:

To systematically synthesize evidence regarding Asian patients’ perspectives on advance care planning and their underlying motives.

Design:

Mixed-method systematic review and the development of a conceptual framework (PROSPERO: CRD42018099980).

Data sources:

EMBASE, MEDLINE, Web of Science, and Google Scholar were searched for studies published until July 27, 2020. We included studies concerning seriously-ill Asian patients’ perspectives on advance care planning or their underlying motives for engaging or not engaging in it.

Results:

Thirty-six articles were included; 22 were quantitative and 27 were from high-income countries. Thirty-nine to ninety percent of Asian patients were willing to engage in advance care planning. Our framework highlighted that this willingness was influenced not only by their knowledge of their disease and of advance care planning, but also by their beliefs regarding: (1) its consequences; (2) whether its concept was in accordance with their faith and their families’ or physicians’ wishes; and (3) the presence of its barriers. Essential considerations of patients’ engagement were their preferences: (1) for being actively engaged or, alternatively, for delegating autonomy to others; (2) the timing, and (3) whether or not the conversations would be documented.

Conclusion:

The essential first step to engaging patients in advance care planning is to educate them on it and on their diseases. Asian patients’ various beliefs about advance care planning should be accommodated, especially their preferences regarding their role in it, its timing, and its documentation.

Keywords: Asian continental ancestry group, critical illness, attitude, patient preference, mixed design, systematic review

What is already known about the topic?

Asian healthcare professionals hold that patients’ family play a central role in advance care planning and rarely engage patients in it.

Despite the wide range of studies on advance care planning in different populations in Asian countries, and despite their variety of methodologies and conceptualizations of advance care planning, there has been no systematic synthesis of their results.

What this papers adds

This study demonstrates that although a majority of Asian patients regarded advance care planning as necessary, more varied results were produced by studies that examined their actual willingness to engage in it.

Willingness to engage in advance care planning was affected not only by patients’ knowledge of their disease and advance care planning, but also by their beliefs: (a) about its advantages or disadvantages; (b) that its concept should be in accordance with patients’ faith and their families’ or physicians’ wishes; and (c) about the presence of barriers to it (e.g. complexities of future planning, socioeconomic dependence, and the unreadiness of the healthcare system).

Implications for practice, theory, or policy

Initial steps toward engaging Asian patients in advance care planning should include: (a) an exploration of their understanding of their disease; and (b) the correction of common misperceptions through education on what advance care planning entails.

Advance care planning for Asian patients needs to accommodate: (a) patients’ widely differing beliefs on it; (b) their preferences regarding the way in which values are communicated, that is, when and by whom; and (c) whether or not it is documented.

Introduction

The implementation of advance care planning has become one of the indicators for high-quality palliative care. 1 Advance care planning enables patients to define, discuss, and record their goals and preferences for future medical treatment and care, and to review these preferences if appropriate. 2 It also aims to clarify and document patients’ values and preferences regarding future medical care, and to ensure these are taken into account at the time of incapacity. 2 To ensure that these values and preferences are acknowledged and can be used to facilitate respectful and responsive care, patients’ involvement in this process is deemed essential. 3

The practice of advance care planning may be affected by societal norms and values.4,5 In our systematic review of Asian healthcare professionals’ perspectives on advance care planning, we found that professionals regard families as playing the leading role in it. 6 However, we also observed that these professionals rarely engage patients in advance care planning, even when the patients retain their decision-making capacity. Among the reasons for not engaging patients was healthcare professionals’ concern about patients’ lack of readiness to engage in advance care planning. 6

To better understand how advance care planning can best be delivered to Asian patients, it is essential to understand their preferences. Although various studies have been conducted in different Asian countries, they used various methodologies and conceptualizations of advance care planning. We therefore aimed to summarize and systematically synthesize the evidence on native Asian patients’ perspectives on advance care planning and their underlying motives.

Methods

This systematic review is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020. 7

Design

This study obtained a phenomenological approach in which we integrated findings of primary quantitative and qualitative studies to build a network of related concepts that together provide a comprehensive understanding of Asian patients’ perspectives on advance care planning.8–10

Data sources and searches

With the aid of a biomedical information specialist (WMB), we developed and deployed a systematic strategy for searching four electronic databases, EMBASE.com (1971-); MEDLINE ALL Ovid (1946-); Web of Science Core Collection (1975-); and Google Scholar from inception to July 27, 2020 (date last searched). Whenever applicable, search terms for each database were tailored using thesaurus terms (Emtree and MeSH; see Supplemental Appendix 1 for the full search strategies). The searches contained terms to describe advance care planning and advance directives, and were also designed to retrieve articles on end-of-life decision-making in Asian countries or among Asian populations. Conference papers, letters, notes, and editorials were excluded from the search, as were articles on children, and articles in languages other than English. We used no limit for publication date or study design. To ensure a comprehensive search, we scanned the reference lists in relevant literature reviews and in the included articles. Lastly, we inquired among different experts on advance care planning in Asia whether we had missed important studies that would met our inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Study selection

Studies were included on the basis of the following inclusion criteria: an original empirical study published in English in peer-reviewed journals that focused on patients with serious illness living in the southern, eastern, and southeastern Asia; and that reported patients’ perspectives on advance care planning, their agreement or willingness to engage in it, the role of decision maker, and the motivational drivers for their willingness or unwillingness to engage in it.

We defined serious illness as a health condition that carried a high risk of mortality and either negatively impacted a person’s daily function or quality of life, or placed an excessive burden on their caregivers. 11 This definition covers severe chronic conditions (such as cancer, renal failure, and advanced liver disease); dementia; and elderly patients living in long-term care facilities.

We further operationalized advance care planning as: (1) activities the authors had labeled as “advance care planning”; and/or (2) activities that involve patients, their family and/or healthcare professionals in discussions of the patients’ goals and/or preferences for future medical care and/or treatment; (3) activities that involve documentation processes of patients’ preferences, including (a) the appointment of a personal representative and (b) writing an advance directive. 2 Due to the vast area of the Asian continent, we focused our search on its southern, eastern, and southeastern regions, whose cultural backgrounds are relatively comparable. 12 We excluded studies on patients under 18 years old or on those diagnosed with mental disorders other than early dementia according to the criteria of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders V. 13

On the basis of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, three authors (DM, MSK, and OG) were involved in independently screening titles and abstracts for eligibility and then reviewing the full-text articles. If necessary, disagreements were discussed and resolved with JR and/or CR. References were managed using Endnote bibliographic software version X9.

Quality assessment and data extraction

Two of the three authors (DM and CPL or DM and OG) were involved in independently assessing the methodological quality of the included studies using the QualSyst tool, which has been described as suitable for various study designs. 14 We employed the 10 standard criteria for qualitative studies and the 14 standard criteria for quantitative studies. Mixed-method studies were evaluated using both sets of criteria. We divided the sum of the scores by the total numbers of criteria. Any disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussion. The summary scores were defined as strong (score of >0.80), good (0.71–0.80), adequate (0.51–0.70), or low (<0.50). 15 Studies were not excluded on the basis of their methodological quality. To ensure that the quality assessment was free of bias, the author who conducted the quality assessment of an included study had not authored that specific paper.

A tailored data-extraction form was developed by DM. After piloting by JR, it was used by DM to extract data that included: (a) study characteristics; (b) patients’ perspectives on advance care planning, including their agreement with its concept and necessities, their willingness to engage in it, and their perspectives on the decision maker in it; (c) motives underlying patients’ willingness or unwillingness to engage in it. The extracted data was then reviewed by OG.

Data synthesis and analysis

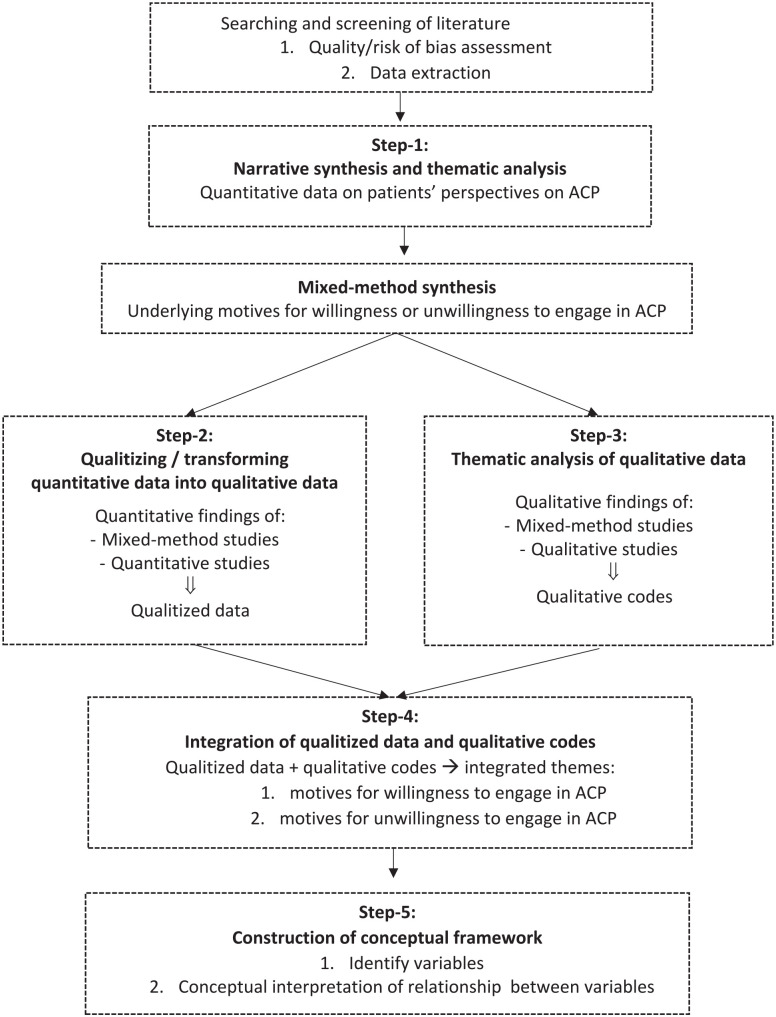

Figure 1 shows the multi-step synthesis and analysis performed on the data. First, to explore patients’ perspectives on advance care planning, we conducted a narrative synthesis and thematic analysis according to Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews (Step-1), 16 which includes textual description of the extracted data, tabulation, grouping, and clustering of data obtained from quantitative findings of quantitative or mixed-method studies. In the second step, we further synthesized patients’ underlying motives for willingness or unwillingness to engage in advance care planning, which we then analyzed on the basis of the type of data. The quantitative data was qualitized—that is, transformed into qualitative data—by attributing a qualitative thematic description to quantitative findings following the Bayesian conversion method.17,18 In the second step, the qualitative data was analyzed separately by DM and OG on the basis of Boeije’s 19 procedure for thematic analysis. Any disagreements were resolved through consensus. In the fourth step, DM and OG further integrated the qualitized data with qualitative codes, using a data-based convergent integrative synthesis design to produce a set of integrated themes. 20 This process was facilitated through a discussion with JR and CR. Qualitative analysis software (NVivo 12 Pro) was used to organize all qualitative data. Finally, in the fifth step we constructed a conceptual framework adapted from the Theory of Planned Behavior in order to visually display the interactions of the underlying motives with regard to patients’ willingness or unwillingness to engage in advance care planning.9,21

Figure 1.

Multi-step synthesis and analysis.

ACP: advance care planning.

Results

Study characteristics

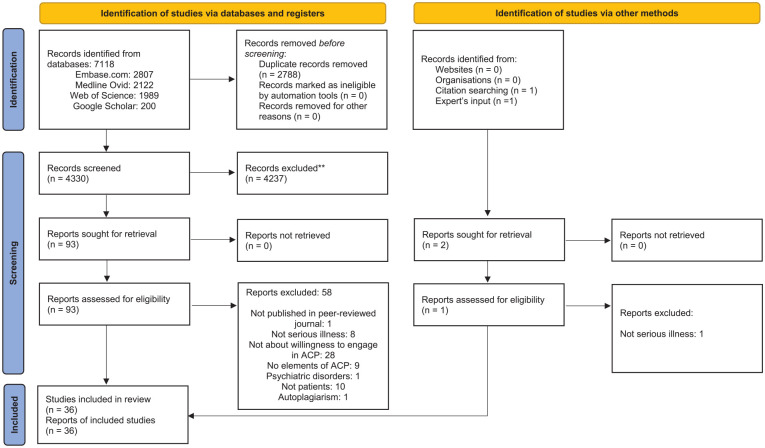

Through our systematic search, we identified 7118 potential studies. After de-duplication, 4330 studies remained, which were then screened on the basis of their titles and abstracts. We further excluded 4237 studies, primarily because they had not studied specific elements of advance care planning. After the addition of two studies identified by expert’s input and a manual search of reference lists, 94 studies were assessed full-text. Ultimately, 36 were included (Figure 2), 22 of which had used quantitative methods, 10 of which had used qualitative methods, and 4 of which had used mixed methods (Table 1 and Supplemental Appendix 2). A majority of the studies (N = 25) had been conducted in high-income countries 22 : Japan,23–26 South Korea,24,27–35 Hong Kong,36–41 Singapore,42–44 and Taiwan.45–50 The term advance care planning was used in 15 studies, most of which had been published in the last decade. Other studies, many of them less recent, used terms such as advance directive or do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order that were related mainly to advance care planning documents; or terms such as end-of-life discussion that were related to advance care planning. Fourteen studies conceptualized advance care planning as the completion of documents (advance directives or DNR orders), while 22 conceptualized advance care planning as a conversation process with or without documentation. Elderly patients (n = 16) and cancer patients (n = 14) were the most-studied patient populations. A majority of studies were conducted in a hospital-based setting (n = 23). Methodological quality was categorized as being strong in 11 studies, good in 11, adequate in 12, and low in 2 (Supplemental Appendices 3 and 4).

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram for study selection.

ACP: advance care planning.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies (n = 36).

| Study characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Type of study | |

| Quantitative study | 22 (61) |

| Qualitative study | 10 (28) |

| Mixed-methods study | 4 (11) |

| Country/region a | |

| South Korea a | 10 |

| China a | 6 |

| Hong Kong | 6 |

| Taiwan | 6 |

| Japan a | 4 |

| Singapore | 3 |

| Malaysia | 3 |

| Term related to ACP used b | |

| Advance care planning | 15 |

| Term related to ACP documents: | |

| Advance directive | 19 |

| DNR order/directive | 2 |

| Physician order for life-sustaining-treatment | 3 |

| Term related to ACP conversation: | |

| End-of-life decision-making | 5 |

| Advance directive decision-making | 1 |

| The element of ACP studied | |

| ACP as completion of documents | 14 |

| ACP as process of discussion on preferences | 13 |

| Both | 9 |

| Number of patients in the study | |

| 0–100 | 15 |

| 101–500 | 17 |

| 501–1000 | 1 |

| >1000 | 3 |

| Type of subjects studied | |

| Patients: | |

| - Cancer | 14 |

| - Non-cancer: | |

| Elderly with chronic serious illnesses | 16 |

| Chronic dialysis | 1 |

| - Not-specified non terminal serious illnesses | 4 |

| - Not-specified terminal illness | 1 |

| Setting | |

| Hospital | 23 |

| Palliative care unit or hospice | 3 |

| Elderly facility | 9 |

| No restriction in the setting | 1 |

ACP: advance care planning; DNR: do-not-resuscitate.

One study was conducted in South Korea, China, and Japan.

Several studies used more than one terms related to advance care planning.

Patients’ perspectives on advance care planning

Patients’ agreement with the importance of advance directive

Seven quantitative studies reported on whether or not patients thought advance directives were important24,31,34,46,51,52,54 (Supplemental Appendix 5). Three-quarters or more of Asian patients in six studies considered they were necessary: Malaysia (75%) 54 ; South Korea (85% 24 ; 87% 31 ; 93% 34 ); China (74% 51 ; 80% 24 ); Japan (96%) 24 ; Taiwan (77%). 46 In the seventh study, also from China, 22% of patients agreed on it. 51

Patients’ willingness to engage in advance care planning or to draft an advance directive

Seven quantitative studies reported that 39%–90% of Asian patients were willing to engage in advance care planning (Table 2). Two of these reported that 62%–82% of patients’ were willing to engage in it together with their family or healthcare professionals. The first of these studies involved patients with advanced cancer in South Korea; 62% of these patients were willing to engage in advance care planning with their family, and 61% with healthcare professionals. 27 In the second of these studies, from China, 82% of patients were willing to engage in advance care planning with their family and/or with their healthcare professionals). 55 In Japan, the willingness to engage in advance care planning with the family (mean score 3.3 ± 0.61, range 1–4) was similar to the willingness to engage in advance care planning without families (mean score 3.2 ± 0.52) among older patients with chronic diseases. 23 Four other studies reported Asian patients’ willingness to engage in advance care planning (39%–68%) without detailing their preferences on whom they would have the conversation with: Singapore (39%–49% of older patients with mild dementia)43,44; Taiwan (42% of nursing home residents) 49 ; and Malaysia (68% of patients with kidney failure). 54

Table 2.

Patients’ willingness to engage in advance care planning or to draft an advance directive.

| No | First author | Year | Country | Type of patient | Conceptualization of ACP | Patients’ willingness to engage in ACP | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Cheong K 44 | 2015 | Singapore | Patients with early cognitive impairment | Advance care planning is a process that aims to inform and facilitate medical decision-making to reflect patients’ values and preferences in the event that they cannot communicate their wishes. | Willing to engage in ACP | 39% |

| 2. | Hing Wong A 54 | 2016 | Malaysia | Patients on routine hemodialysis | Advance care planning is a process of communication among the patients, their families, and professional caregiver, which include, but is not limited to discussing preferences for life-sustaining treatments. | Willing to engage in ACP | 68% |

| 3. | Lo TJ 43 | 2017 | Singapore | Patients with early cognitive impairment | Advance care planning is a process that facilitates decision-making on future care and helps patients with chronic or terminal illnesses make known their wishes before they lose their ability to do so. | Willing to engage in ACP | 49% |

| 4. | Sung HC 49 | 2017 | Taiwan | Elders living in long-term care facility | Advance care planning is a process of discussion between individuals and their physicians, formal caregivers, families, and friends about their preferences and wishes for future care if the individual lacks the capacity to express their wishes. | Willing to engage in ACP | 42% |

| 5. | Hou XT 55 | 2018 | China | Patients with advanced cancer | Advanced care planning is the process whereby there is a discussion between individuals and their physicians, family, and friends about their preferences and wishes for future care at a time when they may lack the capacity to express such wishes. | Willing to engage in ACP: (a) With HCPs and families (b) With HCPs only (c) With families only |

a) 59% b) 12% c) 11% |

| 6. | Kizawa Y 23 | 2020 | Japan | Elderly patients with chronic disease | Not defined | Willingness to engage in ACP

a

: (a) By themselves (b) With families (Mean score ± SD; Range: 1–4) |

a) 3.2 ± 0.52 b) 3.3± 0.61 |

| 7. | Yoo SH 27 | 2020 | South Korea | Patients with advanced solid and/or hematologic cancer | Not defined | (a) Willing to engage in ACP with family • In total • Among those who understand their illness • Among those who don’t understand their illness (b) Willing to engage in ACP with physician • In total • Among those who understand their illness • Among those who don’t understand their illness |

(a) 62% • 67% • 58% (b) 61% • 68% • 56% |

| No | First author | Year | Country | Type of patient | Conceptualization of AD | Patients’ willingness to draft an AD | Percentage |

| 1. | Chu LW 39 | 2011 | Hong Kong | Elderly living in long-term care facility | An advance directive is a statement, usually in writing, in which a person, when mentally competent, indicates the form of healthcare he or she would like to have in a future time when he or she is no longer competent | Willing to draft an AD | 88% |

| 2. | Ting FH 37 | 2011 | Hong Kong | Elderly in-patients with chronic diseases | Not defined | Willing to draft an AD if formally legalized | 49% |

| 3. | Ni P 56 | 2014 | China | Elders living in long-term care facility | An advance directive is a legal document that outlines a person’s care preferences and wishes, should their decision-making ability be diminished as a result of a critical illness or cognitive impairment. | Willing to draft an AD | 32% |

| 4. | Park J 35 | 2016 | South Korea | Elders living in long-term care facility | An advance directive is a written document specifying medical treatments that people want or do not want to receive in the event where the ability to communicate or make decisions is lost due to a progression of illness. | Willing to draft an AD | 59% |

| 5. | Hui EC 38 | 2017 | Hong Kong | Patients with solid cancer (any stage) | Not defined | Willing to draft an AD | 22% (and list treatment preferences); 12% (and assign proxy decision-maker) |

| 6. | An HJ 30 | 2019 | South Korea | Patients with terminal cancer | An advance directive is a legal document written by

anyone regardless of his/her illness, and it includes a

future medical care plan, living will, or designation of

power of attorney. The POLST form is a medical document that mainly pertains to a patient’s future care, including end of life care preferences in case they lose the capacity to make decisions. |

Willing to sign AD (POLST) | 52% |

| 7. | Kim JW 28 | 2019 | South Korea | Patients with advanced solid cancer | POLST is a part of an advance care planning with advance directives and is written by a doctor based on the patient’s wishes at the terminal stage. | Willing to draft AD (POLST) | 71% |

| 8. | Park HY 33 | 2019 | South Korea | Patients with cancer (any stage) | Advance directives are statement that an adult could write about the determination of life-sustaining treatment and utilization of hospice at a terminal stage. | Willing to draft an AD: (a) In a healthy condition (b) When diagnosed with serious illness (c) When the terminal stage is difficult to predict (d) When the condition of serious illness worsened (e) When the terminal stage is easy to predict (f) When diagnosed with terminal stage |

(a) 59% (b) 69% (c) 68% (d) 73% (e) 73% (f) 74% |

| 9. | Feng C 53 | 2020 | China | Patients with lung cancer (any stage) | Advance directives are legal documents in which people choose the medical treatments they are, or are not, willing to receive if in the future they lose the capacity to talk about their wishes. | Willing to sign AD | 80% |

| 10. | Yoo SH 27 | 2020 | South Korea | Patients with advanced solid and/or hematologic cancer | Not defined | (a) Willing to draft an AD: • Among those who understand their illness • Among those who don’t understand their illness (b) Willing to draft POLST • Among those who understand their illness • Among those who don’t understand their illness |

(a) • 55% • 45% (b) • 59% • 49% |

ACP: advance care planning; AD: advance directive, CPR: cardiopulmonary resuscitation; HCPs: healthcare professionals; POLST: physician order for life-sustaining-treatment; SD: standard deviation.

Higher score indicates greater willingness.

Ten studies reported that 32%–88% of Asian patients were willing to draft an advance directive: Hong Kong (88% of nursing home residents, 49% of critically-ill elderly patients, and 34% of cancer patients)37–39; China (32% of nursing home residents and 80% of cancer patients)53,56; and South Korea (52%–74% of advanced cancer patients; 59% of nursing home residents).27,28,30,33,35

Patient’s perspectives on the decision maker in advance care planning

Seven quantitative studies reported the perspectives of Asian patients on their own role, and the roles of their family and physicians, regarding decision-making in advance care planning (Supplemental Appendix 6). Fifty-one to ninety-five percent of Asian patients considered the main decision maker in advance care planning to be themselves, either alone or together with their family members and/or physicians.24,26,28,31,37,38 Five to thirty-one percent of Asian patients preferred their family or physician to be the main decision maker in advance care planning.24,26,28,31,37,38

Four studies compared preferred styles of decision-making, reporting a stronger preference for collective decision-making (i.e. patients together with their family and/or their physicians) than for individualistic decision-making: Japan (61% vs 33%), 24 South Korea (67% vs 27%), 24 China (48% vs 26%), 24 and Hong Kong (71% vs 21%). 38 These findings contrast with two studies among older people with serious illnesses in which individualistic decision-making was preferred: in Hong Kong (14% vs 55%) 37 and South Korea (32% vs 39%). 31

Underlying motives for patients’ willingness or unwillingness to engage in advance care planning

Twenty-two studies (8 quantitative, 10 qualitative, and 4 mixed-method) examined patients’ underlying motives for being willing or unwilling to engage in advance care planning. We summarized the quantitative data in Supplemental Appendix 7 and further transformed them into qualitized data (Table 3). Our analysis of the qualitative data produced 29 qualitative codes (Supplemental Appendix 8), 5 related to willingness, and 24 related to unwillingness to participate in advance care planning.

Table 3.

Underlying motives for patients’ willingness or unwillingness to engage in advance care planning.

| Motivational drivers for engagement in advance care planning | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitized data | Qualitative codes | Integrated themes | Conceptual framework variables |

| Patients’ belief that ACP would ensure their wishes to be respected 37 | Patients’ belief that ACP would promote autonomy25,42,44,57,58 | Patients’ belief that ACP would promote autonomy | Behavioral beliefs |

| Patients’ awareness of future incapacity35,56 | |||

| Patients’ wish to exercise self-determination28,35 | |||

| Patients’ belief that ACP would ensure a comfortable end of life 37 | Patients’ wish to have comfort near the end of their life40,57,58 | Patients’ belief that ACP would enable a comfortable end of life | |

| Patients’ belief that quality of life is more important than length of life 37 | |||

| Patients’ belief that ACP would prevent them from the suffering due to meaningless treatment 28 | |||

| Patients’ belief that ACP would avoid causing burden to the family with end of life decision35,37 | Patients’ wish to avoid being a burden to their family25,42,44,57 or the society 47 | Patients’ belief that ACP would avoid causing burden to the family or society | |

| Patients’ belief that ACP would avoid burdening the society 37 | |||

| Patients’ wish to ease the economic burden on the family 28 | |||

| Patients’ belief that ACP would prevent conflict between family members 37 | Patients’ belief that ACP would create connection with the family 42 | Patients’ belief that ACP would facilitate shared understanding between patient and family | |

| Patients wish that ACP would help family understand their wishes at an early stage 56 | |||

| Patients’ experience with the death of a relative/friend 37 | Patients’ positive experience with ACP45,58 | Patients’ belief that ACP is beneficial after their experience with end of life or ACP | |

| Patients’ religious beliefs 37 | Patients’ religious beliefs | Normative beliefs | |

| Patients’ wish to follow physician’s recommendation for ACP 28 | Patients’ wish to follow physician’s recommendation for ACP | ||

| Motivational drivers for non-engagement in advance care planning | |||

| Qualitized data | Qualitative codes | Integrated themes | Conceptual framework variables |

| Patients’ lack of knowledge of own disease state 30 | Patients’ lack of illness understanding25,36,44,57 | Patients’ lack of illness understanding | Knowledge |

| Patients’ concern of lacking the information needed for decision-making 55 | |||

| Patients’ lack of awareness of AD35,37,56 | Incomplete understanding/lack of awareness regarding ACP41–44,48,50,57,58 | Patients’ limited understanding of ACP | |

| Patients’ lack of knowledge about AD30,33 | Patients’ lack of understanding of ACP relevance for planning beyond financial arrangements43,44 | ||

| Patients’ need of more information 38 | |||

| Patients’ lack of understanding of the policy 28 | |||

| Patients’ lack of idea on how to approach end of life communication 55 | |||

| Patients’ belief that ACP is not useful 56 | Patients inability to appreciate what intent of ACP43,50 | Patients’ belief that ACP is not necessary or beneficial | Behavioral beliefs |

| Patients’ belief that talking about ACP would make their relatives sad 55 | Patients’ concern that ACP would cause distress or burden for family members41,42,48,50,58 | Patients’ concern of implications of ACP | |

| Patients’ concern that ACP would cause conflict within their family members44,50,58 | |||

| Patients’ concern of the psychological discomfort produced when thinking about a terminal illness 33 | Patient’s concern that they would feel uncomfortable discussing end of life issues/lose of hope29,41,42 | ||

| Patients’ discomfort in talking about death 30 | |||

| Patients’ belief that talking about ACP would make them sad 55 | |||

| Patients’ belief that drafting AD would mean giving up or result to being abandoned by the physicians 30 | Patient’s belief that discussing end of life would bring bad luck (taboo)50,58 | ||

| Patients’ belief that signing AD would lead to bad things 30 | |||

| Patients’ uncertainty whether their wish would be respected 33 | Patients’ doubted about the effectiveness of ACP in conveying their wishes 44 | Patients’ doubted about the effectiveness of ACP in conveying their wishes | |

| Motivational drivers for non-engagement in advance care planning | |||

| Qualitized data | Qualitative codes | Integrated themes | Conceptual framework variables |

| Patients’ belief that family does not support their engagement in ACP43,44,47 | Patients’ belief that family does not support their engagement in ACP | Normative beliefs | |

| Patients’ belief that HCPs do not advocate ACP41,43 | Patients’ belief that HCPs do not advocate ACP | ||

| Patients’ wish to let the nature take its course 37 | Patients’ wish to seek harmony with the mandate of nature 50 | Patients’ belief that ACP goes against their faith/religious beliefs | |

| Patients’ religious beliefs 37 | Patients’ belief in providence41,44,48,50,57,58 | ||

| Patients’ concern of difficulties of making decisions in advance 38 | Patients’ concern of difficulty in planning for the unknown/unpredictable disease course25,41,45,50 | Patients’ concern of difficulty in planning for the unknown | Control beliefs |

| Patients’ concern that their decision may change later33,37 | Patients’ concern that their decisions may change in the future29,42 | ||

| Patients considered ACP irrelevant due to their socioeconomic dependency25,43,44,58 | Patients’ sense of limited options for future care | ||

| Patients’ belief of limited options available for them in the future care 25 | |||

| Patients’ belief that limited care continuity hampers ACP 41 | Patients’ sense of the lack of healthcare supporting system for ACP | ||

| Patients’ belief that time constraint from HCPs side hampers ACP 41 | |||

| Patients’ belief that HCPs lack the communication skills and empathy for ACP 41 | Patients’ belief that HCPs lack the skills for ACP | ||

| Willingness to engage in ACP in particular approaches | |||

| Qualitized data | Qualitative codes | Integrated themes | Conceptual framework variables |

| Patient act as sole primary decision maker in ACP24,28,31,37,38 | Patient as independent decision maker in ACP25,42,57,58 | Patients’ preference for active involvement in decision-making, individually | Actors and roles |

| Patient, together with family and/or HCPs, as decision maker in ACP24,31,37,38 | Patient, together with family and/or HCPs, as decision maker in ACP 42 | Patient preference for active involvement in decision-making, together with the family and/or HCPs | |

| Patients’ wish to discuss with the family 28 | |||

| Patients’ wish to entrust decision-making to the relatives30,35,37,38,55,56 | Patients’ wish to entrust decision-making to family members25,36,41–44,50,57,58 | Patients’ preference for passive involvement in decision-making | |

| Patients belief the family will make the best decision on their behalf33,43 | |||

| Patients’ wish to entrust decision-making to the physicians30,35,37,55 | Patients’ belief that the physicians would “do what is right”41,50,57,58 | ||

| Patients’ belief that there is no need to think about drafting an AD now 37 | Patients’ belief that it’s too early to engage in ACP25,50 | Patients’ preference of timing for initiation of ACP | Timing |

| Patients’ belief that it’s too early for ACP 56 | |||

| Patients’ belief that ACP is not necessary in their current age 35 | |||

| Patients’ belief that it’s not the right time yet 28 | |||

| Patients’ need of more time to think28,38 | |||

| Patients belief that drafting an AD is important24,31,34,54 | Patients’ preference of ACP formality | Formality | |

| Patients’ preference to further discuss with family 43 | Patients’ belief that informal planning would suffice29,44,57 | ||

ACP: advance care planning; AD: advance directive, HCPs: healthcare professionals.

By integrating the qualitized and qualitative data, we developed seven integrated themes regarding patients’ motives for willingness to engage in advance care planning (Table 3): (a) their belief that it would promote autonomy; (b) their belief that it would enable a comfortable end-of-life; (c) their belief that it would avoid burden on the family; (d) their belief that it would facilitate shared understanding between patient and family; (e) their past experiences with end-of-life or advance care planning; (f) their religious beliefs; and (g) their wish to follow their physician’s recommendations.

Eleven integrated themes were developed as motives for patients’ unwillingness to engage in advance care planning: (a) their lack of understanding of their illness; (b) their limited understanding of advance care planning; (c) their concerns about its implications; (d) their belief that it was not necessary or beneficial; (e) their uncertainty about its effectiveness in conveying their wishes; (f) their belief that healthcare professionals did not advocate advance care planning; (g) their belief that family did not support their engagement in it; (h) their belief that it went against their faith or religious beliefs; (i) their sense that the options for future care were limited; (j) their sense that it was not yet partially or fully supported by the healthcare system; and (k) their belief that healthcare professionals lacked the skills needed for advance care planning.

Conceptual framework for patients’ willingness to engage in advance care planning

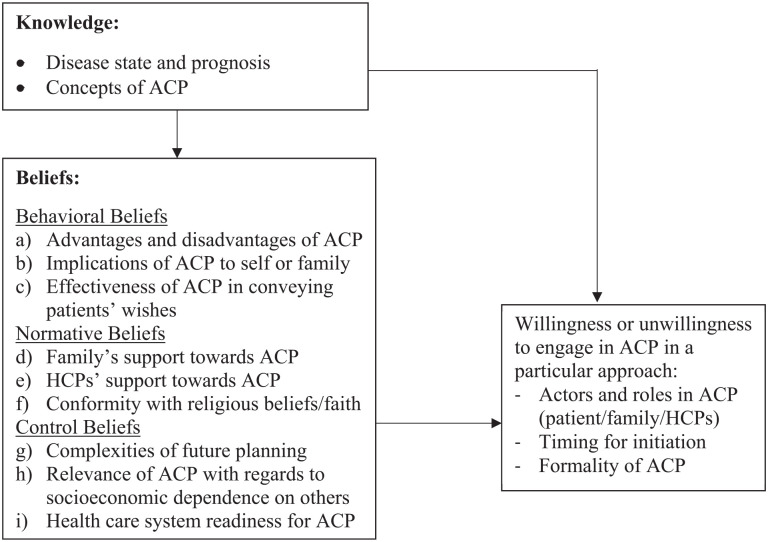

Next, we used these integrated themes to develop a conceptual framework organized on the basis of knowledge, beliefs, and willingness to engage in advance care planning (Figure 3). According to the Theory of Planned Behavior, 21 beliefs in advance care planning were further divided into three types: (a) behavioral beliefs in advance care planning (i.e. patients’ beliefs regarding the likely consequences of engaging in advance care planning); (b) normative beliefs in advance care planning (i.e. the normative expectations of others regarding their engagement in advance care planning); and (c) control beliefs in advance care planning (i.e. the presence of factors that might facilitate or hinder their engagement in advance care planning).

Figure 3.

Conceptual framework for patients’ willingness to engage in ACP.

ACP: advance care planning; HCPs: healthcare professionals.

Patients’ knowledge

Patients who lacked awareness of their disease severity and prognosis25,30,36,44,55,57,58 and/or knowledge regarding advance care planning27,28,30,33,35,37,38,41–44,48,50,55–58 were less likely to engage in it. For instance, patients who had mistakenly understood that advance care planning was merely a discussion about financial arrangements decided not to engage in it if their planning was already sufficient or if they had no assets to plan for.43,44 Our model was based on the hypothesis that patients’ beliefs and willingness to engage in advance care planning were influenced by their knowledge of its concept and of their illness.

Patients’ behavioral beliefs about advance care planning

Studies reported that patients’ beliefs about the benefits of advance care planning were important motivators of their engagement in it; such benefits include the belief that advance care planning promoted autonomy,25,28,35,37,42,44,56–58 enabled a comfortable end-of-life,28,37,40,57,58 avoided burdening family members,25,28,35,37,44,57 and facilitated shared understanding with family members.37,42,56 Conversely, five groups of patients would be less likely to engage in advance care planning: (a) those who believed that it was not beneficial 43,56; (b) those who believed that engaging in it might cause conflict between their family members or distress to them41,42,44,48,50,55,58 or to themselves29,30,33,41,42,55; (c) those who believed that discussing death would bring bad luck30,50,58; (d) those who believed that signing the advance care planning document would lead to substandard care 30 ; and (e) those who were not sure that it would guarantee their wishes were respected.33,44

Patients’ normative beliefs about advance care planning

We identified three normative components of beliefs pertaining to engagement in advance care planning. The first was related to family: patients who believed that their family did not support their engagement in advance care planning43,44,47 would be less likely to engage in it. The second was related to healthcare professionals: patients would be less likely to engage in advance care planning if their physicians did not advise them to do so.41,43 The third was related to faith or religious belief. Seven studies found that patients’ faith or spiritual beliefs were motives for non-engagement in advance care planning.37,41,44,48,50,57,58 Like those who believed that their future was predetermined by God or their past actions and those who believed in the mandate of nature would be likely to accept what they regarded as their predetermined fate rather than attempting to take control of it or modify it through advance care planning.

Patients’ control beliefs about advance care planning

Patients were particularly concerned about the complexities of advance care planning with regard to the difficulties of planning for the unknown25,38,41,45,50 and the possibility of a future change of mind.29,33,37,42 As their socioeconomic dependency on others gave them only limited options for future care, they were concerned that planning for various future scenarios might not be relevant to them.25,44,58 Patients were also concerned that, as they had never had the chance to develop a long-term relationship with a healthcare professional that would make advance care planning possible, the healthcare system might not be supportive of it. 41 They were also concerned that healthcare professionals lacked the skills and empathy needed to engage in it. 41

Patients’ willingness or unwillingness to engage in advance care planning

Our data also shows that willingness or unwillingness depended on three factors: (a) which role people have in advance care planning; (b) when it is initiated; and (c) how formally it is carried out. Patients tended to expect one of the following: (a) active engagement that involved the patient with their family members and/or healthcare professionals24,28,31,37,38,42; or (b) passive involvement in which they preferred to extend their autonomy and entrust decision-making to their family members or healthcare professionals.25,30,33,35–38,41–44,50,55–58 The motivations for entrusting decision-making to family included beliefs that: the family knew the appropriate decision for the patient,41,43,44,50 such decision making was the children’s responsibility to the parents, 50 family would carry out the patient’s wishes, 43 and the patients would have no control over future decision-making. 58 A further motivation was patients’ experience of being treated well by the family. 25 A reason for entrusting decision-making to physicians was a belief that physicians would do what was best for the patient.41,50,57,58 Those who preferred to be their own primary decision maker were motivated by their doubts that the family would honor their wishes, 57 and by their expectation that they would be able to maintain control of their life.25,58

Our findings also show that patients were willing to initiate advance care planning at a particular time in the future or later in the course of their illness.25,28,33,35,37,38,50,56 With regard to patients’ preferences for documenting their conversations, our findings were varied: while some preferred a written document,24,31,34,54 others preferred verbal communication with their family, and/or healthcare professionals without drafting or signing a written document.29,43,44,57

Discussion

To better understand Asian patients’ perspectives on advance care planning and the motives underlying their willingness or unwillingness to engage in it, we systematically synthesized and integrated outcomes from different types of studies, and then developed a conceptual framework on the basis of our findings. Most of these findings originated in high-income Asian countries. Acknowledging the limit we set to our search, the term “Asian patients” we used to describe our findings refers to Asian patients in southern, southeastern, and eastern Asia. Our most important finding is that a majority of Asian patients agreed that advance care planning was necessary. The main motive for their engagement in it concerned its benefits, such as promoting autonomy, allowing a comfortable end of life, avoiding burden on family members, and facilitating shared understanding with family members. Conversely, a range of motives characterized those who were unwilling to engage in it: patients’ lack of understanding of their disease, their misperceptions about advance care planning, and the following beliefs: that it was not beneficial, that it was potentially harmful, that it was not consistent with their religious beliefs or with the wishes of their family or healthcare professionals, and that there were various barriers to it. Our findings suggest that Asian patients would benefit from an individual approach with regard to the individual(s) who should communicate values or be present during advance care planning, the right time for initiating advance care planning conversations, and the formality of advance care planning.

Our study confirms previous findings suggesting that proper understanding of their illness (e.g. prognosis) is an important initial step to patients’ realization of whether or not they would need further conversations on their goals and future care plan.59,60 The poor illness understanding identified in our study is likely to have been caused by limited truth-telling—a common aspect of communication with seriously ill patients in Asia, 6 which leads to their exclusion from conversations about poor diagnosis and prognosis. Healthcare professionals’ tendency toward partial disclosure or non-disclosure is not compatible with most Asian patients’ reported preference for truth-telling communication.61–64 Our study thus provides further confirmation of the fact that clarifying patients’ understanding of their illness (including prognosis) by encouraging truth-telling communication is an important prerequisite for engagement in advance care planning.

Our study also shows that Asian patients have only a limited understanding of what advance care planning entails. Three misperceptions of advance care planning are particularly common: that it is purely a financial planning process, a completion of a formal document, or a conversation related to death and dying. These may be due to the facts that advance care planning is a relatively new concept in Asia that is both complex and continuously evolving, various terms of legislation on advance directives in different countries, and that there is little or no public education on it in Asia.3,65 Correcting these misperceptions whilst simultaneously taking proper account of the Asian context—for example by engaging family members earlier—is central to the promotion of positive attitudes to it. A similar phenomenon has been reported by studies from non-Asian countries, which solidify the influence of participants’ knowledge regarding advance care planning on its delivery across different cultures.66–68

Our earlier systematic review showed that Asian healthcare professionals rarely engaged patients in advance care planning and, in the event of disagreement between patients’ advance directive and the family’s wishes, would defer to the family. 6 However, it is clear from our current findings that a meaningful number of Asian patients expect and prefer active participation in advance care planning, either together with their families, or, to a lesser extent, individually. This suggests that the commonly stereotyped Asian values of passive or family-centered decision-making may in fact be too narrow, and, due possibly to modernization and globalization, that a shift may also be taking place toward more autonomous forms of decision-making. 69 This evidence further emphasizes the importance of avoiding East-West cultural stereotypes and of identifying individual patients’ personal values and preferences for engaging in medical decision-making.

Other important motives for patients’ willingness or unwillingness to engage in advance care planning are beliefs about its harms and benefits. Central to these beliefs is the motivation to protect oneself and one’s loved ones from future suffering, whether (a) physical (such as that due to unwanted treatment in the absence of advance care planning, or to substandard treatment after signing an advance directive); (b) financial (such as that caused by economic burdens on the family); (c) social (such as that due to family conflict); or (d) psychological (such as the distress caused by decision-making as a surrogate or by loss of hope).

Our findings also suggest that certain normative beliefs play an important role in patients’ engagement in advance care planning. Asian patients will favor advance care planning when it is in accordance with a physician’s advice, families’ wishes, or patients’ religious beliefs about the end of life. Particularly in Asian collectivist culture, it is essential to seek harmony with others, including family members, society, and nature. While death is often regarded as God’s will or the mandate of nature, discussing it openly may also be believed to cause bad luck. Open and honest communication on these beliefs and related concerns is therefore essential, not only to allow misperceptions or false beliefs to be corrected, but also to allow approaches to the topic that are more acceptable to a specific patient’s personal values. Acknowledging such beliefs is essential to facilitating an appropriate and patient-centered approach to advance care planning.

Our model also suggests that these beliefs have led to various preferences for role in advance care planning, one of which involves granting autonomy to their family or healthcare professionals, and thus allowing their own values to be communicated, and decisions to be made, by family or healthcare professionals. In this case, advance care planning should facilitate mutual understanding of patients’ values. This would allow for the further translation of these values into relevant goals and preferences without limiting the context of conversations and the patient’s eventual role in the process.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to explore Asian patients’ perspectives on and willingness to engage in advance care planning, and also their underlying motives for this. As advance care planning is an emerging concept in Asia, our comprehensive conceptualization of it made it possible to conduct a sensitive search that did not necessarily use advance care planning as a search term, but nonetheless identified studies examining its relevant elements. The use of mixed-method systematic review enabled us to gain a deeper understanding of the findings by integrating different types of evidence from various types of studies.

When interpreting this systematic review, three main limitations should be taken into account. Firstly, our inclusion solely of studies published in English may have led valuable contributions to be excluded. However, we believe that our comprehensive search strategy, wide inclusion criteria, and mixed-method strategy enabled us to identify sufficient number of studies to answer our research questions. Secondly, there was a possibility of selection bias, as patients with a greater interest in advance care planning may have been more inclined to participate in the studies in question. Finally, our results may lack generalizability to low and middle-income Asian countries, other regions of Asia (i.e. northern, western, and central Asia), and patients with mental disorders.

What this review adds

Our study suggests the importance of developing a culturally sensitive model of advance care planning for Asia. Because decision-making in Asia is primarily family driven, advance care planning should focus on achieving a shared understanding of patients’ values by encouraging open communications and establishing the connection between patients and their family. Our findings may also be relevant to the practice of advance care planning in Western countries, particularly when engaging patients or family members of Asian descent. Healthcare professionals who engage in advance care planning with patients of Asian origin should avoid stereotyping Asian collectivist culture and bear in mind that these patients may prefer active involvement in it. To facilitate a proper approach to advance care planning conversations, healthcare professionals should also familiarize themselves with various beliefs about advance care planning that are commonly found in Asian culture. With regard to these beliefs, our findings suggest that the focus of advance care planning conversations should be shifted from merely communicating care objectives toward exploring and establishing values, and thereby achieving truly value-concordant care. A separate review is currently underway and aims to explore whether the phenomenon in Asians living in foreign countries is comparable to our current findings and how acculturation may play role in it. 70

Conclusion

The essential first steps toward engaging Asian patients in advance care planning involve a process of education and clarification, in which various misperceptions about their illness and prognosis are resolved, and it is clearly established what advance care planning entails. Advance care planning for Asian patients should be able to accommodate the diversity of patients’ beliefs; their preferences with regard to their role in it, either as active participants, or by delegating responsibility to family members or healthcare professionals; decisions on the best time to initiate it; and decisions on formally documenting it.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-pmj-10.1177_02692163211042530 for Asian patients’ perspectives on advance care planning: A mixed-method systematic review and conceptual framework by Diah Martina, Olaf P Geerse, Cheng-Pei Lin, Martina S Kristanti, Wichor M Bramer, Masanori Mori, Ida J Korfage, Agnes van der Heide, Judith AC Rietjens and Carin CD van der Rijt in Palliative Medicine

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Maarten F.M. Engel for his support with the search process.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Conception and design: DM, OG, WMB, MM, AH, CR, JR; Collection and assembly of data: DM, OG, CPL, MSK, WMB, MM, CR, JR; Data analysis and interpretation: All authors; Manuscript writing: All authors; Final approval of manuscript: All authors.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval was not required due to the type of review (narrative review of literature).

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education (Lembaga Pengelola Dana Pendidikan, LPDP) of the Indonesian Ministry of Finance (grant number 201711220412068). The funding body had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

ORCID iDs: Diah Martina  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0889-223X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0889-223X

Olaf P Geerse  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8864-4887

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8864-4887

Cheng-Pei Lin  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5810-8776

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5810-8776

Martina S Kristanti  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6609-6285

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6609-6285

Ida J Korfage  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6538-9115

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6538-9115

Judith AC Rietjens  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0538-5603

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0538-5603

Data management and sharing: All the relevant data are available. The method of data collection and screening process was reported in the main text (Figure 2). The search strategy can be found in the Supplemental Appendix 1. The data used from the included study are clearly described in the manuscript.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Planning and implementing palliative care services: a guide for programme managers. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/250584 (2016, accessed 19 May 2020).

- 2. Rietjens JAC, Sudore RL, Connolly M, et al. Definition and recommendations for advance care planning: an international consensus supported by the European association for palliative care. Lancet Oncol 2017; 18(9): e543–e551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lin CP, Cheng SY, Mori M, et al. 2019 Taipei declaration on advance care planning: a cultural adaptation of end-of-life care discussion. J Palliat Med 2019; 22: 1175–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McDermott E, Selman LE. Cultural factors influencing advance care planning in progressive, incurable disease: a systematic review with narrative synthesis. J Pain Symptom Manag 2018; 56: 613–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zager BS, Yancy M. A call to improve practice concerning cultural sensitivity in advance directives: a review of the literature. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2011; 8: 202–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Martina D, Lin CP, Kristanti MS, et al. Advance care planning in Asia: a systematic narrative review of healthcare professionals’ knowledge, attitude, and experience. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2021; 22: 349.e1–349.e28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The Prisma 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021; 372: n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Purssell E, McCrae N. Reviewing qualitative and quantitative studies and mixed-method reviews. In: How to perform a systematic literature review: a guide for healthcare researchers, practitioners and students. 1st ed. London: Springer, 2020, pp.113–116. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jabareen Y. Building a conceptual framework: philosophy, definitions, and procedure. Int J Qual Methods 2009; 8: 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health research. 4th ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kelley AS, Bollens-Lund E. Identifying the population with serious illness: the “denominator” challenge. J Palliat Med 2018; 21: S7–S16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. United Nations. Standard country or area codes for statistical use (m49), https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/ (1999, accessed 29 October 2020).

- 13. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: APA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kmet LM, Cook LS, Lee RC. Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. Edmonton, AB: AHFMR, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Best M, Aldridge L, Butow P, et al. Treatment of holistic suffering in cancer: a systematic literature review. Palliat Med 2015; 29: 885–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Chapter 3: Guidance on narrative synthesis-an overview. In: Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme (version 1). Swindon: ESRC, 2006, pp.16–20. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lizarondo L, Stern C, Carrier J, et al. Chapter 8: mixed-methods systematic reviews. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z. (eds) JBI manual for evidence synthesis. Adelaide: JBI, 2020, pp.121–131. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pearson A, White H, Bath-Hextall F, et al. A mixed-methods approach to systematic reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015; 13: 121–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Boeije HR. Analysis in qualitative research. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hong QN, Pluye P, Bujold M, et al. Convergent and sequential synthesis designs: implications for conducting and reporting systematic reviews of qualitative and quantitative evidence. Syst Rev 2017; 6: 61–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ajzen I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. J Appl Soc Psychol 2002; 32: 665–683. [Google Scholar]

- 22. World Bank. World bank country and lending groups. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (2020, accessed 5 January 2020).

- 23. Kizawa Y, Okada H, Kawahara T, et al. Effects of brief nurse advance care planning intervention with visual materials on goal-of-care preference of Japanese elderly patients with chronic disease: a pilot randomized-controlled trial. J Palliat Med 2020; 23: 1076–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ivo K, Younsuck K, Ho YY, et al. A survey of the perspectives of patients who are seriously ill regarding end-of-life decisions in some medical institutions of Korea, China and Japan. J Med Ethics 2012; 38: 310–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hirakawa Y, Chiang C, Hilawe EH, et al. Content of advance care planning among Japanese elderly people living at home: a qualitative study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2017; 70: 162–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Voltz R, Akabayashi A, Reese C, et al. End-of-life decisions and advance directives in palliative care: a cross-cultural survey of patients and health-care professionals. J Pain Symptom Manag 1998; 16: 153–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yoo SH, Lee J, Kang JH, et al. Association of illness understanding with advance care planning and end-of-life care preferences for advanced cancer patients and their family members. Support Care Cancer 2020; 28: 2959–2967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kim JW, Choi JY, Jang WJ, et al. Completion rate of physician orders for life-sustaining treatment for patients with metastatic or recurrent cancer: a preliminary, cross-sectional study. BMC Palliat Care 2019; 18: 84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Koh SJ, Kim S, Park J, et al. Attitudes and opinions of elderly patients and family caregivers on end-of-life care discussion. Ann Geriatr Med Res 2017; 21: 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- 30. An HJ, Jeon HJ, Chun SH, et al. Feasibility study of physician orders for life-sustaining treatment for patients with terminal cancer. Cancer Res Treat 2019; 51: 1632–1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Park SY, Kim OS, Cha NH, et al. Comparison of attitudes towards death and perceptions of do-not-resuscitate orders between older Korean adults residing in a facility and at home. Int J Nurs Pract 2015; 21: 660–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lee J, Kim KH. Perspectives of Korean patients, families, physicians and nurses on advance directives. Asian Nurs Res 2010; 4: 185–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Park HY, Kim YA, Sim JA, et al. Attitudes of the general public, cancer patients, family caregivers, and physicians toward advance care planning: a nationwide survey before the enforcement of the life-sustaining treatment decision-making act. J Pain Symptom Manag 2019; 57: 774–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Keam B, Yun YH, Heo DS, et al. The attitudes of Korean cancer patients, family caregivers, oncologists, and members of the general public toward advance directives. Support Care Cancer 2013; 21: 1437–1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Park J, Song JA. Predictors of agreement with writing advance directives among older Korean adults. J Transcult Nurs 2016; 27: 574–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cheng HB, Shek PK, Man CW, et al. Dealing with death taboo: discussion of do-not-resuscitate directives with Chinese patients with noncancer life-limiting illnesses. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2019; 36: 760–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ting FH, Mok E. Advance directives and life-sustaining treatment: attitudes of Hong Kong Chinese elders with chronic disease. Hong Kong Med J 2011; 17: 105–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hui EC, Liu RK, Cheng AC, et al. Medical information, decision-making and use of advance directives by Chinese cancer patients in Hong Kong. Asian Bioeth Rev 2016; 8: 109–133. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chu LW, Luk JKH, Hui E, et al. Advance directive and end-of-life care preferences among Chinese nursing home residents in Hong Kong. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2011; 12: 143–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chan CWH, Wong MMH, Choi KC, et al. What patients, families, health professionals and hospital volunteers told us about advance directives. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs 2019; 6: 72–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cheung JTK, Au D, Ip AHF, et al. Barriers to advance care planning: a qualitative study of seriously ill Chinese patients and their families. BMC Palliat Care 2020; 19: 80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Menon S, Kars MC, Malhotra C, et al. Advance care planning in a multicultural family centric community: a qualitative study of health care professionals’, patients’, and caregivers’ perspectives. J Pain Symptom Manag 2018; 56: 213–221.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lo TJ, Ha NH, Ng CJ, et al. Unmarried patients with early cognitive impairment are more likely than their married counterparts to complete advance care plans. Int Psychogeriatr 2017; 29: 509–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cheong K, Fisher P, Goh J, et al. Advance care planning in people with early cognitive impairment. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2015; 5: 63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lin CP, Evans CJ, Koffman J, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of a culturally adapted advance care planning intervention for people living with advanced cancer and their families: a mixed methods study. Palliat Med 2020; 34: 651–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chou HH. Exploring the issues of advance directives in patients with mild dementia in Taiwan. Acta Med Okayama 2020; 74: 215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lin CP, Evans CJ, Koffman J, et al. What influences patients’ decisions regarding palliative care in advance care planning discussions? Perspectives from a qualitative study conducted with advanced cancer patients, families and healthcare professionals. Palliat Med 2019; 33: 1299–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lee HTS, Chen TR, Yang CL, et al. Action research study on advance care planning for residents and their families in the long-term care facility. BMC Palliat Care 2019; 18: 95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sung HC, Wang SC, Fan SY, et al. Advance care planning program and the knowledge and attitude concerning palliative care. Clin Gerontol 2019; 42: 238–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lee HT, Cheng SC, Dai YT, et al. Cultural perspectives of older nursing home residents regarding signing their own DNR directives in eastern Taiwan: a qualitative pilot study. BMC Palliat Care 2016; 15: 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zheng RJ, Fu Y, Xiang QF, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and influencing factors of cancer patients toward approving advance directives in China. Support Care Cancer 2016; 24: 4097–4103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zhang Q, Xie C, Xie S, et al. The attitudes of Chinese cancer patients and family caregivers toward advance directives. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2016; 13: 816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Feng C, Wu J, Li J, et al. Advance directives of lung cancer patients and caregivers in China: a cross sectional survey. Thorac Cancer 2020; 11: 253–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hing Wong A, Chin LE, Ping TL, et al. Clinical impact of education provision on determining advance care planning decisions among end stage renal disease patients receiving regular hemodialysis in University Malaya Medical Centre. Indian J Palliat Care 2016; 22: 437–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hou XT, Lu YH, Yang H, et al. The knowledge and attitude towards advance care planning in Chinese patients with advanced cancer. Psycho-Oncol 2018; 27: 65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ni P, Zhou J, Wang ZX, et al. Advance directive and end-of-life care preferences among nursing home residents in Wuhan, China: a cross-sectional study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2014; 15: 751–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Htut Y, Shahrul K, Poi PJ. The views of older Malaysians on advanced directive and advanced care planning: a qualitative study. Asia Pac J Public Health 2007; 19: 58–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Jiao NX, Hussin NA. End-of-life communication among Chinese elderly in a Malaysian nursing home. J Patient Exp 2018; 7: 62–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ng QX, Kuah TZ, Loo GJ, et al. Awareness and attitudes of community-dwelling individuals in Singapore towards participating in advance care planning. Ann Acad Med Singap 2017; 46: 84–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Tang ST, Chen CH, Wen FH, et al. Accurate prognostic awareness facilitates, whereas better quality of life and more anxiety symptoms hinder end-of-life care discussions: a longitudinal survey study in terminally ill cancer patients’ last six months of life. J Pain Symptom Manag 2018; 55: 1068–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yun YH, Kwon YC, Lee MK, et al. Experiences and attitudes of patients with terminal cancer and their family caregivers toward the disclosure of terminal illness. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 1950–1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Rajasooriyar C, Kelly J, Sivakumar T, et al. Breaking bad news in ethnic settings: perspectives of patients and families in northern Sri Lanka. J Glob Oncol 2017; 3: 250–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Sankar SD, Dhanapal B, Shankar G, et al. Desire for information and preference for participation in treatment decisions in patients with cancer presenting to the department of general surgery in a tertiary care hospital in India. J Glob Oncol 2018; 4: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ghoshal A, Salins N, Damani A, et al. To tell or not to tell: exploring the preferences and attitudes of patients and family caregivers on disclosure of a cancer-related diagnosis and prognosis. J Glob Oncol 2019; 5: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Cheng SY, Lin CP, Chan HY, et al. Advance care planning in Asian culture. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2020; 50: 976–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Johnson S, Butow P, Kerridge I, et al. Advance care planning for cancer patients: a systematic review of perceptions and experiences of patients, families, and healthcare providers. Psychooncology 2016; 25: 362–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. El-Jawahri A, Paasche-Orlow MK, Matlock D, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of an advance care planning video decision support tool for patients with advanced heart failure. Circulation 2016; 134: 52–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Carter G, McLaughlin D, Kernohan WG, et al. The experiences and preparedness of family carers for best interest decision-making of a relative living with advanced dementia: a qualitative study. J Adv Nurs 2018; 74: 1595–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Alden DL, Friend J, Lee PY, et al. Who decides: me or we? Family involvement in medical decision making in eastern and western countries. Med Decis Making 2018; 38: 14–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zhu T, Martina D, Rietjens J, et al. The role of acculturation on the process of ACP among Chinese adults living in western countries. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=231822 (2021, accessed 28 June 2021).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-pmj-10.1177_02692163211042530 for Asian patients’ perspectives on advance care planning: A mixed-method systematic review and conceptual framework by Diah Martina, Olaf P Geerse, Cheng-Pei Lin, Martina S Kristanti, Wichor M Bramer, Masanori Mori, Ida J Korfage, Agnes van der Heide, Judith AC Rietjens and Carin CD van der Rijt in Palliative Medicine