Abstract

Background

Mutual support groups play an extremely important role in providing opportunities for people to engage in alcohol and other drug (AOD) treatment and support. SMART Recovery groups employ cognitive, behavioural and motivational principles and strategies to offer support for a range of addictive behaviours. COVID-19 fundamentally changed the way that these groups could be delivered.

Methods

A series of online meetings were conducted by the lead author (PK) and the SMART Recovery International Executive Officer (KM), with representatives from the SMART Recovery National Offices in the Ireland (DO), United States (MR), Australia (RM), and Denmark (BSH, DA), and the United Kingdom (AK). The meetings focused on discussing the impacts of COVID-19 on SMART Recovery in each of the regions.

Results

As a result of restrictions to prevent the transmission of COVID-19, the vast majority of SMART Recovery face-to-face meetings were required to cease globally. To ensure people still had access to AOD mutual support, SMART Recovery rapidly scaled up the provision of online groups. This upscaling has increased the number of groups in countries that had previously provided a limited number of online meetings (i.e., United States, England, Australia), and has meant that online groups are available for the first time in Denmark, Ireland, Hong Kong, Spain, Malaysia and Brazil.

Discussion

Whilst the urgent and rapid expansion of online groups was required to support people during the pandemic, it has also created an opportunity for the ongoing availability of online mutual support post-pandemic. The challenge for the research community is to critically evaluate the online delivery of mutual support groups, to better understand the mechanisms through which they may work, and to help understand the experience of people accessing the groups.

Keywords: SMART Recovery, COVID-19, Mutual support, 12-Step, e-Health, Telehealth, Internet

A major challenge in the alcohol and other drug (AOD) treatment field is increasing access to treatment for a greater proportion of people impacted by AOD use (Kohn, Saxena, Levav, & Saraceno, 2004; Ritter, Chalmers, & Gomez, 2019). This ‘treatment gap’ has significant health and wellbeing consequences for individuals, and major social and economic impacts on society more broadly. Mutual support groups play an important role in helping to address this gap. With no waiting list or cost to attend, and a range of group types and locations, it is not surprising that mutual support groups are one of the most widely accessed forms of AOD treatment globally (Dawson, Grant, Stinson, & Chou, 2006; England, 2013; Kelly, Bergman, Hoeppner, Vilsaint, & White, 2017). Mutual support groups also often compliment other forms of treatment approaches. Although twelve-step groups are the most well-known examples of mutual support, a range of other mutual support approaches help provide people with choice in relation to their treatment needs (Zemore, Lui, Mericle, Hemberg, & Kaskutas, 2018).

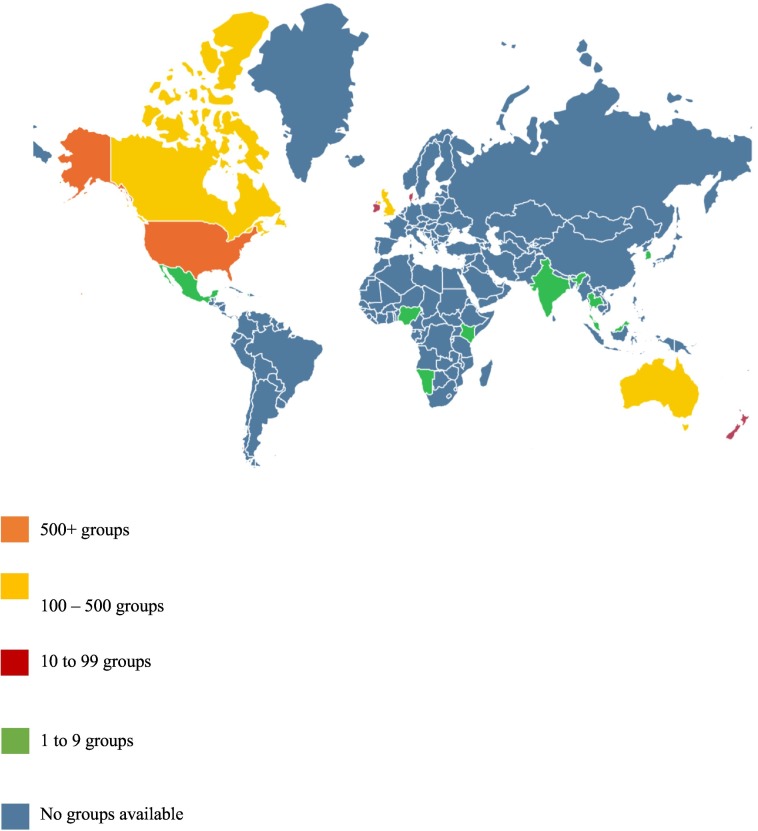

SMART Recovery is a widely available mutual support group. The groups are available across 23-countries (see Fig. 1 ). SMART Recovery was developed to reflect evidence based cognitive behaviour therapy and motivational interviewing approaches to AOD treatment. Each group is led by a trained facilitator, who may be a health professional or non-professional volunteer (e.g., a peer or person with a lived experience of problem substance use and recovery). There is a small but developing body of research supporting the use of SMART Recovery (Beck et al., 2017; Manning, Kelly, & Baker, 2020; Zemore et al., 2018).

Fig. 1.

Number of SMART Recovery groups available globally prior to COVID-19.

1. SMART Recovery International response to COVID-19

SMART Recovery was substantially impacted by COVID-19. Pre-COVID-19, there were more than 3000 face-to-face SMART Recovery groups provided globally (SMART Recovery International, 2021), almost all of which were required to close to comply with infection control restrictions, especially ‘social distancing’. To ensure that people still had access to mutual support during the COVID-19 restrictions, SMART Recovery International focused on a rapid transition to online delivery. The online groups are delivered in a consistent to way to the face-to-face groups. Like face to face groups (Horvath & Yeterian, 2012), they are supported by a trained facilitator and incorporate aspects of cognitive behavioural therapy, motivational interviewing, and goal setting.

As reported by the SMART Recovery national offices, pre-COVID-19 there was a relatively small number of online SMART Recovery groups in the United States (40-groups), England (5-groups) and Australia (6-groups). Across these three countries, the focus has been on rapidly increasing the proportion of online groups available. In the United States, for example, over 1200 online groups were made available during the pandemic. In countries where online groups were not previously available, the transition has been more challenging, requiring the development of local infrastructure to support online groups and to train online facilitators. The increased international collaboration required to support the proliferation of these online meetings, has been a particularly encouraging outcome. It has included countries sharing procedures and resources. As a result, online meetings are now available for the first time across Denmark, Ireland, Hong Kong, Spain, Malaysia and Brazil.

2. Benefits and opportunities

SMART Recovery's rapid and co-ordinated effort to expand online service provision has helped to ensure that mutual support has remained available during the pandemic. The expansion of online groups is important for people affected by AOD use, given the role that mutual support groups play in meeting the growing demand for treatment and support. Moreover, people affected by AOD use are disproportionately vulnerable to disconnection and loneliness (Ingram et al., 2020), and this has been heightened during the pandemic. Social connection and support are important aspects of recovery (Kaskutas, Bond, & Humphreys, 2002). Mutual support groups help maintain connectedness and a sense of belonging (Ingram, Kelly, Deane, Baker, & Dingle, 2020; Manning et al., 2020). The expansion of online meetings has meant that SMART Recovery has been able to address these important interpersonal needs (albeit at a different level to that of face-to-face (Gentry, Lapid, Clark, & Rummans, 2019)) under pandemic conditions.

The expansion of online mutual support groups has created additional opportunities. As demonstrated during COVID-19 and other types of disasters (e.g., 2019–2020 Australian bushfires), online groups provide opportunities to access mutual support where face-to-face meetings are not available (e.g. rural areas; Bergman, Greene, Hoeppner, & Kelly, 2018; Mellor & Ritter, 2020). They also provide increased opportunities for anonymity. For example, group members can choose to turn off their camera and use a pseudonym as their display name. This anonymity is particularly important for people who may be reluctant to attend face-to-face meetings due to stigma (Bliuc, Doan, & Best, 2018). They also help to provide much greater choice in terms of the increased range of meetings that people can attend. Online meetings also provide an opportunity for providers to creatively consider how they might structure or target meetings to increase access for people. For example, this might include offering groups for specific populations (e.g., veterans, people with co-occurring issues of concern, Indigenous populations, gender specific groups), or other forms of complementary group sessions (e.g., mindfulness groups).

3. What these changes will mean for the future of SMART Recovery and mutual support

As social distancing restrictions begin to ease, face-to-face mutual support groups will progressively return. There is a long-standing and strong tradition of face-to-face mutual support, and their resumption will once again help to provide opportunities for people to access AOD treatment. Whilst the urgent and rapid expansion of online groups was required to support people during the pandemic, it has also created an opportunity for SMART Recovery, and potentially other forms of mutual support, to continue to offer more online groups post-COVID-19. The greater provision of online groups has profound implications for meeting the growing need for accessible AOD support options.

Prior to COVID-19, there was limited up-take of online groups across the range of mutual support available (e.g., Alcoholics Anonymous, SMART Recovery). For example, in a nationally representative survey of US adults who had ‘resolved’ an AOD use concern (i.e. indicated that they previously had ‘a problem with drugs or alcohol but no longer do’ (Bergman et al., 2018; Kelly et al., 2017)), 45% of respondents reported using a mutual support group (Bergman et al., 2018; Kelly et al., 2017). However, only 4% of respondents reported that they had used any form of online mutual support group (Bergman et al., 2018). For SMART Recovery, the coordinated international experience of providing online groups during COVID-19 has demonstrated to the broader SMART Recovery community (i.e., group members, facilitators, and administrators) that online groups are a feasible way of providing mutual support. Now that the infrastructure to support online meetings has been developed, and there is increased expertise in the delivery of online SMART Recovery groups, SMART Recovery is well placed to continue to provide online groups. However, it is also important to acknowledge that online delivery of mutual support is costly (e.g., licences for online platforms, computers, internet). Government grants have helped to support the transition of SMART Recovery to online groups during the COVID-19 restrictions. Accordingly, SMART Recovery will need to increasingly work with governments, funding bodies, and other service providers to ensure that online groups are still available for participants following COVID-19.

4. Implications for research

The challenge for mutual support services and organisations is ensuring that online meetings meet the needs of group participants. Online service provision raises particular questions regarding confidentiality, infrastructure availability, engagement and group cohesion (Marhefka, Lockhart, & Turner, 2020; Weinberg, 2020). Whilst there is evidence of people in recovery utilising online mutual support (Bergman et al., 2018), there is a lack of research in this area (Ashford, Bergman, Kelly, & Curtis, 2019). As highlighted in recent editorials and reviews addressing COVID-19, it is likely that online mutual support groups (e.g., Alcoholics Anonymous, SMART Recovery) will offer benefit for individuals and help to utilise similar therapeutic mechanisms addressed in face-to-face groups (Bergman & Kelly, 2021; Bergman, Kelly, Fava, & Eden Evins, 2021). However, it is important that research continues to examine the effectiveness of online groups (e.g., comparing online and face-to-face groups), and in particular, examine the potential mechanisms through which these groups may work. Additionally, research is needed to understand who attends online groups, what the uptake of the groups are, how people use these groups (e.g., as the only form of treatment, as a supplement to face-to-face meetings), and why people attend online meetings (e.g., ease of access, anonymity). Group satisfaction and group member experience should also be examined using a combination of qualitative and quantitative research strategies (Davis et al., 2019; Hinsley, Kelly, & Davis, 2019). Research should also examine strategies to improve access to these groups and consider ways to enhance participant experiences and outcomes. For example, it may include strategies to strengthen group cohesion and maximise group attention and engagement in collective problem solving.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Authors PK, AB, VM, AS, LH and BL are voluntary members of the SMART Recovery Australia Research Advisory Committee. Authors DO, AK, RM, AA, MR, BSH, and DA are either paid or voluntary members of SMART Recovery in their respective regions. KM is the Executive Director for SMART Recovery International. All authors contributed to the development and writing of the manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

Authors PK, AB, VM, AS, LH and BL are voluntary members of the SMART Recovery Australia Research Advisory Committee. Authors DO, AK, RM, AA, MR, BSH, and DA are either paid or voluntary members of SMART Recovery in their respective regions. KM is the Executive Director for SMART Recovery International.

References

- Ashford R.D., Bergman B.G., Kelly J.F., Curtis B. Systematic review: Digital recovery support services used to support substance use disorder recovery. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies. 2019, Sep 10;2(1):18–32. doi: 10.1002/hbe2.148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A.K., Forbes E., Baker A.L., Kelly P.J., Deane F.P., Shakeshaft A.…Kelly J.F. Systematic review of SMART recovery: Outcomes, process variables and implications for research. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2017;31(1):1–20. doi: 10.1037/adb0000237. (Accepted 28th October 2016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman B.G., Greene M.C., Hoeppner B.B., Kelly J.F. Expanding the reach of alcohol and other drug services—Prevalence and correlates of US adult engagement with online technology to address substance problems. Addictive Behaviors. 2018, Dec 01;87:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman B.G., Kelly J.F. Online digital recovery support services: An overview of the science and their potential to help individuals with substance use disorder during COVID-19 and beyond. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2021, Jan;120(108152) doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman B.G., Kelly J.F., Fava M., Eden Evins A. Online recovery support meetings can help mitigate the public health consequences of COVID-19 for individuals with substance use disorder. Addictive Behaviors. 2021, Feb;113(106661) doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliuc A.-M., Doan T.-N., Best D. Sober social networks: The role of online support groups in recovery from alcohol addiction. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology. 2018, Nov 12;29(2):121–132. doi: 10.1002/casp.2388. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis E.L., Kelly P.J., Deane F.P., Baker A., Buckingham M., Degan T., Adams S. The relationship between patient-centered care and outcomes in specialist drug and alcohol treatment: A systematic literature review. Substance Abuse. 2019 doi: 10.1080/08897077.2019.1671940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson D.A., Grant B.F., Stinson F.S., Chou P.S. Estimating the effect of help-seeking on achieving recovery from alcohol dependence. Addiction. 2006;101(6):824–834. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England P.H. A briefing on the evidence-based drug and alcohol treatment guidance recommendations on mutual aid. 2013. http://scholar.google.comjavascript:void(0)

- Gentry M.T., Lapid M.I., Clark M.M., Rummans T.A. Evidence for telehealth group-based treatment: A systematic review. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2019, Jul;25(6):327–342. doi: 10.1177/1357633x18775855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinsley K., Kelly P.J., Davis E. Experiences of patient-centred care in alcohol and other drug treatment settings: A qualitative study to inform design of a patient-reported experience measure. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2019, Oct 02;38(6):664–673. doi: 10.1111/dar.12965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath A.T., Yeterian J. SMART recovery: Self-empowering, science-based addiction recovery support. Journal of Groups in Addiction & Recovery. 2012;7(2–4):102–117. doi: 10.1080/1556035x.2012.705651. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram I., Kelly P.J., Deane F.P., Baker A.L., Dingle G.A. Perceptions of loneliness among people accessing treatment for substance use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2020, Jul;39(5):484–494. doi: 10.1111/dar.13120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram I., Kelly P.J., Deane F.P., Baker A.L., Goh M.C.W., Raftery D.K., Dingle G.A. Loneliness among people with substance use problems: A narrative systematic review. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2020, Apr 20;4:106–137. doi: 10.1111/dar.13064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaskutas L.A., Bond J., Humphreys K. Social networks as mediators of the effect of alcoholics anonymous. Addiction. 2002, Jul 01;97(7):891–900. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J.F., Bergman B., Hoeppner B.B., Vilsaint C., White W.L. Prevalence and pathways of recovery from drug and alcohol problems in the United States population—Implications for practice, research, and policy. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2017, Dec 01;181:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn R., Saxena S., Levav I., Saraceno B. The treatment gap in mental health care. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2004, Nov 01;82:858–866. doi: 10.1590/S0042-96862004001100011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning V., Kelly P.J., Baker A.L. The role of peer support and mutual aid in reducing harm from alcohol, drugs and tobacco in 2020. Addictive Behaviors. 2020, Oct;109(106480) doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marhefka S., Lockhart E., Turner D. Achieve research continuity during social distancing by rapidly implementing individual and group videoconferencing with participants: Key considerations, best practices, and protocols. AIDS and Behavior. 2020, Jul;24(7):1983–1989. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02837-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellor R., Ritter A. Redressing responses to the treatment gap for people with alcohol problems: The overlooked role of untreated remission from alcohol problems. Sucht. 2020;66(1):21–30. doi: 10.1024/0939-5911/a000640. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter A., Chalmers J., Gomez M. Measuring unmet demand for alcohol and other drug treatment: The application of an Australian population-based planning model. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2019, Jan;(s18):42–50. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2019.s18.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMART Recovery International . 2021. What is SMART Recovery. (Retrieved 10th June 2021 from) [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg H. Online group psychotherapy: Challenges and possibilities during COVID-19—A practice review. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice. 2020;24(3):201–211. doi: 10.1037/gdn0000140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zemore S.E., Lui C., Mericle A., Hemberg J., Kaskutas L.A. A longitudinal study of the comparative efficacy of Women for Sobriety, LifeRing, SMART Recovery, and 12-step groups for those with AUD. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2018, May;88:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2018.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]