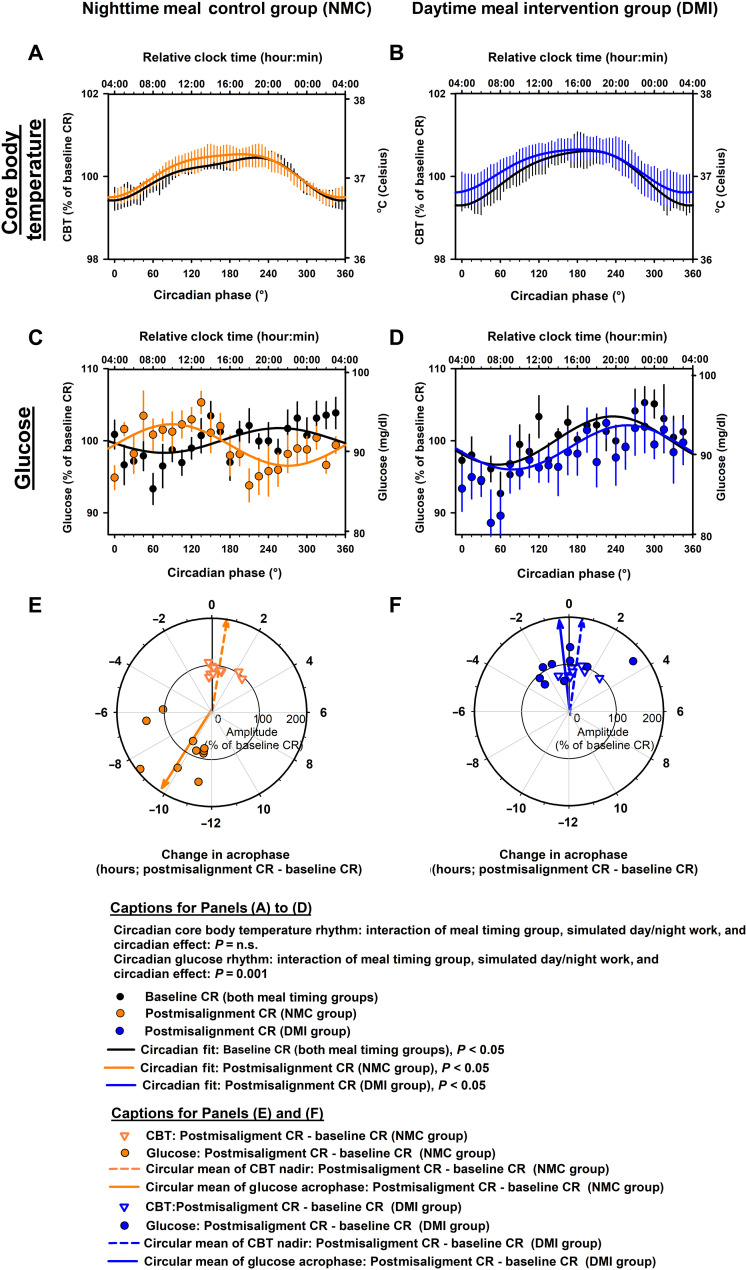

Fig. 2. Effects of meal timing intervention on central and peripheral circadian rhythms after simulated night work.

(A and B) The meal timing intervention did not significantly modify the impact of simulated night work on the endogenous circadian CBT rhythms. Accordingly, simulated night work did not significantly affect the endogenous circadian CBT rhythms, as compared to baseline, in the NMC group (A) or in the DMI group (B). (C and D) The meal timing intervention significantly modified the impact of simulated night work on the endogenous circadian glucose rhythms. Accordingly, simulated night work significantly affected the endogenous circadian glucose rhythms, as compared to baseline, in the NMC group (C), but not in the DMI group (D). (E and F) The change from baseline to simulated night work in the phase of the endogenous circadian CBT rhythms did not significantly differ between groups [inverted triangles in (E) and (F)]. In contrast, the change from baseline to simulated night work in the phase of the circadian glucose rhythms significantly differed between groups [circles in (E) and (F)]. In the NMC group, the phase shift of the endogenous circadian glucose rhythms closely matched the 12-hour shift of the sleep/wake cycle induced by the 28-hour FD protocol (which was not observed in the DMI group). Data in (A) to (D) were grouped into 15°-circadian windows (~1-hour resolution) with SEM error bars and the top x axes were scaled to the approximate group-averaged time of the CBT minimum for reference (i.e., relative clock time). Data in (A) to (D) correspond to the average (mean ± SEM) across participants per simulated day/night work condition and per meal timing group (n = 10 in the NMC group and n = 9 in the DMI group). Individual (symbols) and group-averaged (arrows) data are presented in (E) to (F).