Abstract

Teamwork skills are recognized as a core competency of physicians. To more effectively prepare trainees for the demands of their future work, medical educators are increasingly turning to group-based instructional formats. We employ case-based collaborative learning (CBCL) — a format which requires daily in-class discussion and collaboration in assigned small groups. While students overwhelmingly embraced CBCL as stimulating and thought-provoking, some students reported that social dynamics among group members adversely impacted their experience. Using mixed methods, we demonstrate that a short intervention that asked students to discuss how they can best learn together improved small group dynamics, and promoted psychological safety among peers. Importantly, no specific instruction in team work was required, students overall had a clear understanding how they could improve, but they did not know how to start this conversation with each other. To promote team learning, we propose that educators emphasize students’ accountability to their peers’ learning in addition to their own, and devote some time in class for teams to reflect and discuss how to improve learning with each other. Our observations are of interest to anyone frequently relying on group work without peer assessment or formal feedback on group performance.

Keywords: Case-based collaborative learning, Team-based learning, Educational quality improvement, Psychological safety

Introduction

Teamwork skills are increasingly recognized as a core competency of physicians and a necessity for safe, high-quality patient care [1–3]. Recent decades have seen a steady increase in group-based instructional formats that educators hope will promote deeper learning and teamwork, preparing their learners for the demands of their future careers [4]. The most well-established and widely used group-based methods in undergraduate medical education are problem-based learning (PBL) [5] and Team-Based Learning™ (TBL) [6, 7]. The original paradigm of TBL is that dedicated instruction in teamwork is not necessary since students will gain these skills through the processes of peer assessment and feedback embedded in the format itself [6]. PBL, in contrast, relies on faculty to facilitate the small group process, and as such faculty have a large effect on how well groups work [8]. However, educators increasingly recognize that explicit instruction in team learning, regardless of the specific instructional method used, might be essential for learners to acquire these complex skills [9–11].

Borrowing principles form both PBL and TBL, Harvard Medical School (HMS) developed a novel approach called case-based collaborative learning (CBCL) [12]. In this “flipped classroom” model, students acquire new information by completing preparatory assignments as individuals before applying that knowledge in class, where they work with peers to solve clinical problems. Once presented a case, small groups of three to four students struggle with the problem independently before faculty moderate a discussion with the other small groups in the classroom to consolidate the main points. CBCL was incorporated as the predominant format of the preclinical curriculum with the implementation of the Pathways curriculum in the fall of 2015 [13].

While students generally enjoyed the CBCL format as highly stimulating and engaging [12], they also occasionally reported interpersonal conflicts that lead to disruption and disengagement from classroom activities in confidential conversations with faculty, course evaluation data, and meetings with student curriculum representatives [14]. Neither the peer assessment and feedback components that support teams in TBL nor the extent of faculty facilitation that supports teams in PBL are currently present in CBCL. These anecdotal complaints prompted us to determine the scale of this problem, and further understand how we could support CBCL group dynamics conducive to learning of all members.

Materials and Methods

In designing this educational quality improvement project, we adopted a constructivist approach under which the research questions evolved over the course of the study in light of our preliminary findings [15]. More specifically, we used a mixed-methods triangulation design where equal status was given to the qualitative and quantitative data [16]. The HMS Institutional Review Board deemed this study exempt, as the data was collected for educational quality improvement.

Context

This study was conducted with first-year medical and dental students enrolled in the HMS Pathways curriculum. Pathways involves one course at a time, and students spend four mornings a week in class. Each day, there are 4 concurrent classrooms with 1–3 facilitator(s) and ~ 42–44 students each. The discussion alternates between the students working in small groups of 3–4 followed by a class-wide debrief. This sequence unfolds several times in an iterative fashion as the case materials grow more complex. In total, students spend roughly half of their time in class working independently in their small groups. This study’s data were collected during a required course on the physiology and pathophysiology of the respiratory, cardiovascular, and hematologic systems that runs in the spring term for 9 weeks. Student group assignments changed once, mid-course.

Measures

In 2017, baseline data without an intervention were gathered at three time points (week 2, week 4, week 6) to look for changes in group dynamics over time. In 2018, data were gathered at week 4 (first group rotation, no intervention), and compared with data gathered at week 8 (second group rotation, with intervention) (see Fig. 1 for a timeline). To measure team dynamics, we used a previously validated Team Performance Survey (TPS) initially developed for TBL medical school formats [17]. The TPS is a short, 18-item questionnaire (< 5 min to complete) that assesses team interactions overall in context of a collaborative classroom environment. The original TPS included a 7-option scale (0 = none of the time, 6 = always) that we adapted to 5 options (never, rarely, sometimes, often, always) for simplicity. In addition, we added two open-ended questions to the TPS asking the students to comment on the following: (1) What is one thing that your team has done well? (2) What is one thing that your team could improve on?

Fig. 1.

Median TPS score by data collection time point. Students were randomly assigned to a small group by course leadership. After 4 weeks, group rotations were switched. To understand how they were doing in their small groups, students were asked to complete the TPS survey at weeks 2, 4, and 6 in 2017. No intervention took place that year, and no difference in median TPS score was observed across the course. In 2018, students were asked to complete the TPS survey at the end of each group rotation (week 4 and week 8). A team norming intervention was piloted in the second half of the course. Upon intervention, a small but significant improvement in the median TPS score was detected using the Mann–Whitney U test (U = 103,315.5, p = 0.005) with a Cohen’s d effect size of 0.394

In 2017, students completed the surveys on their own time, and TPS and free responses were anonymous besides the level of the class section (collected on Qualtrics, Provo, UT). No change in TPS score was observed over time, and the aggregated 2017 data were used (1) to serve as historic control (Fig. 1), and (2) to develop a codebook for qualitative analysis of the 2018 data. In 2018, students were provided class time to complete the surveys via the online course management platform Canvas (Instructure, Inc., Salt Lake City, UT). Using student identifiers in Canvas, one of the authors (H.B.) linked responses between surveys for the 2018 data set, and introduced a unique identifier for each CBCL group. Once the linkage was established, all identifiable information was permanently deleted prior to analysis. In all situations, participation in the surveys was voluntary.

Intervention

CBCL teams are randomly assigned for 4 weeks at a time. In 2018, TPS baseline data were gathered after the first team rotation (18w4). For their second team rotation, all students participated in an intervention, and TPS data were gathered at the end of that rotation (18w8). The intervention consisted of two short sessions during regular class time in which students were instructed to discuss how to best work together and develop team norms. Norming is a common practice in business and this specific norming intervention was designed by a medical student with experience in management consulting (Supplemental File 1 contains the description of the intervention).

Quantitative Data Analysis

Across the three survey administrations in the 2017 cohort, response rates decreased from 90 of 170 students (53.0%) in week 2 to 68 students (40.0%) in week 6, not surprising since this survey was given outside of class. In contrast, for the 2018 cohort which received class time to complete the survey, the response rate was 165 out of 169 students (97.6%) in week 4 (18w4, no norming intervention), and 161 out of 169 students (95.3%) in week 8 (18w8, groups with norming intervention). TPS scores were normalized to range from 20 to 100. Differences between groups were assessed using the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test through an online calculator (SocSciStatistics.com) due to the non-normal, independent nature of the data. Cohen’s d effect size was calculated through a different online calculator (Lenhard, W. & Lenhard, A. (2016). Calculation of Effect Sizes. Retrieved from: https://www.psychometrica.de/effect_size.html. Dettelbach (Germany): Psychometrica. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.17823.92329).

Qualitative Data Analysis

We analyzed 416 free response comments for each of the “Done well” and “Improve” questions across all data sets using an inductive coding approach [18]. H.B. and M.K. independently reviewed all free responses and developed a preliminary codebook involving descriptions of each theme and inclusion and exclusion criteria. M.K. and D.K. then independently coded the 2017 free responses according to this scheme before resolving discrepancies and further refining the codebook (Table 1). They finally used this revised codebook to code the 18w4 and 18w8 free responses. Quotations serving to illustrate each theme were selected by M.K. and evaluated by D.K. to ensure adequate representativeness. Cohen’s kappa was calculated using Stata 14. Students’ comments were thematically rich, with an average of 1.5 codes assigned per “Done well” comment, 1.1 codes assigned per “Improve” comment, and very few comments not receiving any codes. Cohen’s kappa averaged across all codes was 0.765, indicating excellent inter-rater reliability [19]. The student free responses in the Done well and Improve prompts of a given theme often addressed the same underlying behaviors and issues, implying the themes had strong construct validity. The same codebook was then used by M.K. to code the group norms developed during the intervention. M.K. also selected representative quotations to illustrate particularly compelling group stories.

Table 1.

Theme development. Representative quotations from the question “What is one thing your team has done well?”

| Theme | Representative quotations |

|---|---|

| Preparedness |

“We are able to apply concepts from the reading to the cases effectively because we are well prepared.” “We are an engaged group. We are all interested in the material, pay attention, and seek to answer the questions.” |

| Promoting balanced participation | “We use a systematic approach to idea-sharing to ensure that everyone has a chance to take the lead and voice their opinion. We all take time to develop our own answers before sharing them with the group. When it comes time to share with the group, we rotate leadership around the four of us, with each subsequent person taking the lead each time we tackle a new question.” |

| Ensuring universal understanding | “We always take extra time to explain to a team member who doesn’t understand the concept to ensure that we cover gaps in each other’s learning.” |

| Psychological safety |

“I think members in the team are willing to listen to different ideas without interrupting or without being rude and giving consideration to each idea.” “We were really positive and fostered a ‘low stakes’ learning environment where members could feel comfortable throwing around ideas without the pressure of feeling like they had to get the ‘right’ answer.” |

| Grappling and synthesis |

“Discussing lots of ideas before deciding what the correct answer is.” “Take each person’s points of view to help further our overall team consensus.” |

| Large group learning | “Speak up when no one else in the class was speaking. Volunteered our discussion.” |

Results

Conceptual Model of CBCL

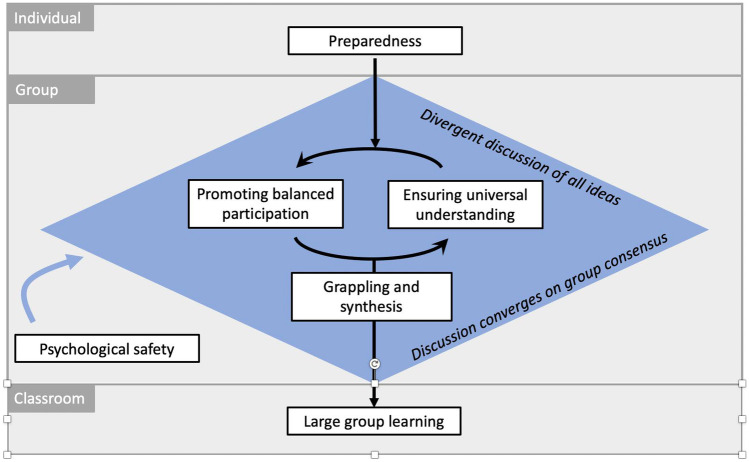

To understand how CBCL teams work, we asked each student to complete a validated team performance scale [17] paired with two open-ended questions to name one thing that was working well, and another that could be improved. Our analysis of free responses revealed six key themes—preparedness, promoting balanced participation, ensuring universal understanding, grappling and synthesis, psychological safety, and large group learning (Table 1). The six themes encompass three domains: Individual, Group, and Classroom processes and together yield a conceptual model of the idealized interactions and processes that occur in CBCL groups (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Conceptual model of functional CBCL processes. Preparedness describes responsibilities of individual students to prepare for class (i.e., having done the assigned readings as homework, timeliness, etc.). The next domain encompasses the small group discussion where students debate the case-based problems without direct faculty supervision. The small group discussion involves an initial divergent stage, in which students solicit their peers’ ideas. This involves two co-existing themes: promoting balanced participation and ensuring universal understanding. The former describes how groups actively solicit the different points of view of all of their members. For example, going around in a circle to ensure everyone has a chance to speak, or reserving some quiet time at the start of their discussion to ensure that everyone has had a chance to formulate their own thoughts before they hear from others. Separate is a commitment to ensuring that all group members understand the topics of discussion and explain their proposed solutions to those who might not. Once all group members are on the same page, groups engage in a second-stage convergent discussion in which they settle on one group answer that they can present to the class. This often involves students reconciling discrepant interpretations and grappling with and synthesizing views that differ from ones they initially held. When done well, these small group behaviors create psychological safety [20] by normalizing risk-taking as part of daily practice and promoting learning as a joint endeavor with all members accountable to each other, not just themselves. Once the group has settled on a solution, they then have the opportunity to report it out to the other groups in their classroom in a discussion moderated by faculty. CBCL classes toggle between small group discussion and large group learning iteratively while progressively solving the case

In this model the actions in the Group domain are divided into two phases, a diverging discussion in which students solicit new ideas, and a converging phase in which they settle on a single group response. Psychological safety [20] emerges in groups where participation is balanced and students work to ensure everyone understands the topics of discussion. It also provides the basis for grappling and synthesis until the group arrives at a consensus that they are willing to present to faculty and other classmates.

Individual Students’ Experience

Having created a conceptual model for how CBCL teams work, we wanted to understand what distinguished teams that worked well from those that worked less well. While the majority of students were somewhat in the middle, nearly a fifth of students rated their groups with almost perfect scores, while an approximately equal number of students comprised a left-sided tail of notably lower scores (Fig. 3A). In order to allow stratification of the qualitative data by TPS scores, we empirically divided TPS scores into three categories: Low (red bars, TPS score less than or equal to 75), Middle (blue bars, TPS score greater than 75 to 95), and High (green bars, TPS greater than 95). Little difference in results was seen by changing these margins slightly while ensuring the n of each group was large enough to make meaningful comparisons.

Fig. 3.

TPS scores and free responses stratified by theme frequencies. A Histogram of TPS % scores from groups that were assigned without norming intervention (2018w4). Low-, Middle-, and High-TPS scores categories denoted in different colors. B Free responses to “name one thing your team could improve on” were coded, and theme frequencies stratified by TPS score category corresponding to panel A. Comments about a lack of psychological safety, balanced participation, and universal understanding were comparatively overrepresented in Low-TPS groups. C Histogram of TPS % scores from groups that were presented with the norming intervention (2018w8). The median TPS score was higher in this groups, illustrated by fewer low-TPS groups and an increase in high TPS groups. D Free responses to “name on thing your team could improve on” were coded and stratified by TPS score category corresponding to panel C. The overall number of “improve” comments was slightly reduced by ~ 18%

When comparing the qualitative comments about what was working well and what could be improved, they were remarkably rich across TPS scores. To our surprise, comments were very similar between middle and high TPS scores, suggesting that after reaching a certain threshold, a small difference in the TPS score may be more indicative of personal preferences than granular differences in how well teams function. However, the low-TPS group was different. Comments about needing to improve psychological safety were enriched in the low-TPS group (Fig. 3B), indicating that some students did not find their teams conducive to their learning. For example, one student wrote “There was one dominant personality in my group who often came across as condescending and not valuing the opinions of women… I never brought it up because the guy who was the main issue had been doing this from the beginning”.

These findings indicated that the TPS tool was useful in identifying low-performance groups that lacked psychological safety in the CBCL context. They also suggested that students were inherently aware of issues with their teams, but did not know how to address them. Interestingly, even students that rated their teams highly still had many ideas for further improvement, suggesting that a conversation about how to learn together benefited all students regardless of how well teams seemed to be working.

Intervention

We piloted an intervention that was designed to build on the students’ inherent awareness of what was working and what needed improvement in their groups. We arranged for students to have 20 min class time to share preferences about learning in CBCL groups and agree on group norms (see Supplemental File 1 for a detailed description of the intervention). A couple of weeks later, we gave them another 15 min to check in with each other and adjust norms if needed. Group norms for all 42 groups were analyzed using the code book developed earlier (Table 1), with representative examples displayed in Table 2. Group norms addressed an average of 3.0 of the six unique themes. The most commonly mentioned themes were promoting balanced participation (in 80% of groups), individual preparation and focus, ensuring universal understanding, and psychological safety (each in about 55% of groups).

Table 2.

Examples of group norms developed by 2 different well-performing teams

| Group norms | Themes |

|---|---|

| Group 1 (group TPS 92, SD 9) | |

| Encourage dissenting opinions | Grappling and synthesis |

| Do not interrupt other people | Psychological safety |

| Ensure that everyone is ready before discussion (using name cards to indicate readiness) | Balanced participation |

| Explain thought processes behind answers | Ensuring understanding |

| Take turns leading the questions so that everyone has a chance to speak | Balanced participation |

| Group 2 (group TPS 95, SD 5) | |

| Be as punctual as possible. Things happen and it’s okay to be late sometimes, but not all the time | Preparedness |

| Reach group consensus on an answer and make sure each person understands why a particular answer was reached (recap of conclusions and summarize what remains confusing towards end of discussion) | Grappling and synthesis |

| Be sure to elicit differing opinions and bring it up (have person explain their POV or thoughts) to ensure that everyone is on the same page | Ensuring understanding |

| No team leader but everyone should feel comfortable initiating table discussions; if this becomes problem (awkward silences during table discussions), we will re-assess | Balanced participation |

| Person who has best grasp of an answer can share it with the larger group/class if they are comfortable doing so; if it’s the same person every time, we can re-evaluate and discuss how to ensure more participation in large group discussions |

Ensuring understanding Balanced participation Large group |

| Let table know if there’s anything confusing from lecture or larger group discussions; if time allows, we can discuss and go over concepts as a group | Ensuring understanding |

Despite the commonality of the themes, there were important differences in the particulars of students’ decisions. For example, one group specified that they would identify a group leader for each discussion question; another group explicitly decided not to appoint a leader and noted that the group would reconsider if things were not going as well as they would like. In all, we found that there was no one “right” way to go about CBCL group work. Rather, the norming activity seemed to make students aware of what they were doing, and to empower them to shape their group dynamics to what worked best for them.

The median TPS score of the intervention data set was 92.2%, which was statistically significantly greater (p < 0.005) than the median TPS score for those groups earlier in the course, that had not spent time setting norms, as well as the historic control data (Fig. 1). With the norming intervention, fewer students rated their groups in the Low-TPS category, our empirical threshold for dysfunction (Fig. 3C). The stratified thematic analysis showed a ~ 18% reduction in “needs improvement” comments overall (Fig. 3D). Comments about needing improvement related to psychological safety, universal understanding, and grappling and synthesis were reduced across all groups, regardless of TPS category. Notably, all groups also continued to have ideas on how to improve, suggesting that they embraced the spirit of continuous improvement in which the norming activity was presented.

Group-Level Experience

The TPS score histograms indicated that individual students had a range of experiences in their CBCL groups. As a second step, we were interested to understand how consistent these experiences were among students within a single team. To answer that question, we aggregated TPS scores by team and compared both scores and free responses between different teams. Figure 4 compares the mean and SD of groups in the no intervention group with those groups that were given the norming intervention. The median team TPS % score pre-intervention was 78%, and post intervention 82%. This presents a significant improvement in overall team TPS % scores using the Mann–Whitney U test (U = 664.5, p = 0.01) with a Cohen’s d effect size of 0.561.

Fig. 4.

Team profile distribution, with and without norming intervention. The vertical bar at 75 separates Low-TPS “Toxic” groups from “Well-Performing” Middle- and High-TPS groups. The “Asymmetric” region contains groups with a high team TPS SD, indicating discrepant experiences among group members (SD of 14.0 = one SD above the mean SD of all groups). The intervention was associated with an improvement of group profiles as indicated by the disappearance of Toxic groups, a decrease in the number of Asymmetric groups, and an increase of Well-Performing groups

The previous stratified qualitative analysis suggested that individuals who rated their groups below 75 were more likely to identify the environment as unsafe. If a group’s average TPS score was below that cutoff, we characterized the team as “Toxic.” Since the previous analysis demonstrated that students in Middle- and High-TPS groups had roughly the same perceptions on areas for improvement, those data points were grouped into a single “Well-Performing” profile. However, to also capture students that may have discrepant experiences within a group, we created an “Asymmetric” profile to denote groups with a group TPS SD one SD above the mean SD of all groups.

Figure 4 shows that the intervention was associated with elimination of groups labeled as Toxic, and a decrease in the number of groups labeled as Asymmetric. Analysis of the comments suggested that the norming intervention created a more consistent and cohesive experience in class, and may have prevented interactions that otherwise would have led to toxic relationships.

Consider, for example, this comment from a student in a Toxic team in the no intervention group, illustrating the emotional strain these teams can take on students:

I think it was very hard for me at the table at first because often one member would jump into answering the question immediately and respond with the answer as opposed to the process. This was frustrating, as we often skipped the thought process and thus important misconceptions […]. I also felt hesitant to speak up because the pattern had been to jump directly to the answer, which is not how I am able to think. It was exhausting trying to counteract this every day, especially at the end of the day. I felt like there was no effort to try and reign their responses in. Sometimes, it felt like there was no room for wrong answers as well, because some group members discounted someone else's response. I noticed that the other female member of the group became quieter over time as well. It did not feel like a collaborative effort.

The low-TPS ratings and needs improvement comments of the other students on the team indicated that they were at least somewhat aware of this dynamic, and that this adverse experience may have been prevented by setting norms. Compare this with a comment from a student in a well-functioning team:

We were all very self-aware and never had one individual speak too much or overpower the conversation. We generally alternated the person who shared ideas first, but not in a too organized or structured way (sometimes I think it is draining to always assign people to talk or answer a specific question, so it is nice when people are aware enough to alternate and share ideas naturally). […] I also think we did a really nice job of having all members share our answers with the large group. I really felt like everyone fully participated.

Interestingly, no discernable qualitative difference was found between norms of different teams, suggesting that once students reached a certain threshold of psychological safety fueled by balanced participation, ensuring understanding, and active synthesis, teams worked together happily in many different ways. We conclude that the norming intervention helped all teams to maximize learning, and made learning in class more inclusive and consistently positive for all members of the class.

Discussion

This study presents a “look under the hood,” characterizing first-year medical student interactions in a small group learning format. While students in both cooperative and team learning arrangements can benefit from efforts to teach and analyze group process skills, such attention can be especially helpful for smaller, shorter-term groups like those used in CBCL [7]. Prior to this analysis, it was not clear that CBCL groups would behave as real teams, since the CBCL setting is not easily classified as either team-based or cooperative based on the literature [7]. Our data clearly indicate that most CBCL groups indeed engage in interdependent work like a true “team” that is more than the sum of its parts [21].

Teamwork is critical to the modern workplace in almost any field, and our understanding of how teams work has expanded greatly in the last several decades. A team is simply put a group of more than two people working interdependently towards a shared goal. To be successful, they must master both goal-related tasks and team-related processes, including establishing effective and inclusive communication patterns, approaching conflict proactively, and creating a culture that embraces similarities and values differences, among others [22]. All of these themes were echoed in our analysis suggesting that CBCL provides students with a valuable opportunity to practice teamwork skills.

However, we also learned that about a fifth of all students experienced team dynamics suboptimal for their learning. CBCL does not include formal peer assessment, an element that is considered critical in TBL. The quality of team interactions was noticeably improved with an intervention that simply asked students to spend a few minutes on discussing team process and how to learn together. This relatively small investment of class time (~ 30 min total over a 1-month group rotation) was associated with quantitative and qualitative improvements in individual- and group-level assessments. This finding is in line with a study by Chen et al. describing that supplementing TBL with guided reflections and other activities resulted in increased appreciation for teamwork [23].

How is it that such a norming intervention can promote group learning? Implicit in peer-learning arrangements like CBCL is the notion that peers are “safer” learning partners than faculty because they are at the same status level [24]. This study presents data that would challenge this notion: within peer groups, there were a significant number of individuals who perceived the learning environment as psychologically unsafe [20]. A number of features including dissimilarities in personality types, different prior experiences and expertise, unconscious bias, and diverging goals for the class may all result in different status assessments among peers [25, 26]. The literature on psychological safety in medical school contexts primarily relates to mistreatment and the implications of its absence [27]. This project indicates that a relatively low-key norming intervention can promote psychological safety among peers and may be an important curricular element to consider for anyone relying on group work without peer assessment or formal feedback on group performance.

A second factor promoting group learning behaviors is accountability [20]. The free responses indicated that even though students were able to identify a number of ways in which their groups could improve, including the most well-functioning teams, they had little incentive to seek this conversation with their peers. Creating time and space during class for students to discuss their team process sends a message that students are accountable not only for their own learning but also for that of their peers. This sets in motion a process where the individual awareness can rise to group-level awareness and eventually alter the group-level interactions and “group learning” can occur [28]. By providing groups an opportunity to explicitly discuss team goals and in-class activities, the norming intervention was a way to ensure everyone was committed to working towards shared objectives in both the group and larger classroom setting [29, 30]. Similarly to how educators promote accountability to prepare for class by assigning quizzes on the homework and recording classroom attendance, educators considering group- or team-based formats need to promote the expectation that students will actually contribute to their teams [31].

Limitations

Our assessments and interventions occurred within the context of a fully operational curriculum with minimal opportunity for manipulation; a trial with a concurrent control group was not possible. The consistency in TPS scores across the three time points in the 2017 cohort and first time point in the 2018 cohort would strongly suggest that the increase in TPS score seen in the second time point of 2018 is attributable to the intervention, but without randomly assigned control group we cannot be certain.

Our primary outcomes related to students’ voluntary contribution of TPS scores and free responses, rather than objective data on team performance. Given limited demographic data, we cannot ensure a lack of systematic differences between students who participated and those who did not. In addition, many factors could have influenced the particular elements of their group work that a student decided to share or withhold, and future studies may be able to shed more light on this.

Conclusions

Group-based learning formats like CBCL provide students an opportunity to develop teamwork skills that will be fundamental to their careers, but negative interpersonal dynamics may impair students’ ability to benefit fully from these formats. Students may benefit from support in addressing these dynamics. A minimal investment of classroom time for students to discuss group process can help improve the learning environment. Educators should be mindful of promoting psychological safety and group-level accountability in their classrooms.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Alex Kazberouk for designing the pilot intervention while an MD/MBA candidate at HMS, Dr. Amy Sullivan for advice on the analysis, and Dr. Richard Schwartzstein for giving us permission to pilot this intervention during his course.

Funding

NA.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

The Harvard Medical School Institutional Review Board deemed this study exempt from formal review.

Informed Consent

NA.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hughes AM, Salas E. Hierarchical medical teams and the science of teamwork. Virtual Mentor. 2013;15(6):829–833. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2013.15.6.msoc1-1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weller J, Boyd M, Cumin D. Teams, tribes and patient safety: overcoming barriers to effective teamwork in healthcare. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90(1061):149–154. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosen MA, et al. Teamwork in healthcare: key discoveries enabling safer, high-quality care. Am Psychol. 2018;73(4):433–450. doi: 10.1037/amp0000298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Medical Association. Creating a Community of Innovation. Chicago, IL. American Medical Association; 2017.

- 5.Davis MH, Harden RM. AMEE Medical Education Guide No. 15: problem-based learning: a practical guide. Med Teach. 1999;21(2):130–140. doi: 10.1080/01421599979743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parmelee D, Michaelsen LK, Cook S, Hudes PD. Team-based learning: a practical guide: AMEE Guide No. 65. Med Teach. 2012;34(5):e275–e287. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.651179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fink LD. Beyond small groups: harnessing the extraordinary power of learning teams. In: Michaelsen LK, Knight AB, Fink LD, editors. Team-based learning: a transformative use of small groups. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2002. pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hmelo-Silver CE. Problem-based learning: what and how do students learn? Educ Psychol Rev. 2004;16(3):235–266. doi: 10.1023/B:EDPR.0000034022.16470.f3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheakley ML, Bauler LD, Tanager CL, Newby D. Student perceptions of a novel approach to promote professionalism using peer evaluation in a Team-Based LearningTM setting: a quality improvement project. Med Sci Educ. 2019;29(4):1229–1232. doi: 10.1007/s40670-019-00830-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Earnest MA, Williams J, Aagaard EM. Toward an optimal pedagogy for teamwork. Acad Med. 2017;92(10):1378–1381. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peterson M. Skills to enhance problem-based learning. Med Educ Online. 1997;2(1):4289. doi: 10.3402/meo.v2i.4289. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krupat E, Schwartzstein RM, Fleenor TJ, Sullivan AM, Richards JB. Assessing the effectiveness of case-based collaborative learning via randomized controlled trial. Acad Med. 2015;91(5):723–729. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwartzstein RM, et al. The Harvard Medical School Pathways Curriculum: reimagining developmentally appropriate medical education for contemporary learners. Acad Med. 2020;95(11):1687–1695. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scott KW, et al. Fostering student-faculty partnerships for continuous curricular improvement in undergraduate medical education. Acad Med. 2019;94(7):996–1001. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Willig C. Introducing qualitative research in psychology. J Chem Inf Model. 2013;9:1689–1699. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schifferdecker KE, Reed VA. Using mixed methods research in medical education: basic guidelines for researchers. Med Educ. 2009;43(7):637–644. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson BM, et al. Evaluating the quality of learning-team processes in medical education: development and validation of a new measure. Acad Med. 2009;84(10):S124–S127. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b38b7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas DR. Method Notes A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval. 2006 doi: 10.1177/1098214005283748. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleiss JL. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. 2. New York: John Wiley; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edmondson A. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Adm Sci Q. 1999;44(2):350. doi: 10.2307/2666999. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hackman JR. A real team. In: Hackman JR, editor. Leading teams: setting the stage for great performances. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press; 2002. pp. 37–60. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salas E, Shuffler ML, Thayer AL, Bedwell WL, Lazzara EH. Understanding and improving teamwork in organizations: a scientifically based practical guide. Hum Resour Manage. 2015;54(4):599–622. doi: 10.1002/hrm.21628. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen W, McCollum MA, Bradley EB, Nathan BR, Chen DT, Worden MK. Using instrument-guided team reflection and debriefing to cultivate teamwork knowledge, skills, and attitudes in pre-clerkship learning teams. Med Sci Educ. 2018;29:45–50. doi: 10.1007/s40670-018-00669-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lockspeiser TM, O’Sullivan P, Teherani A, Muller J. Understanding the experience of being taught by peers: the value of social and cognitive congruence. Adv Heal Sci Educ. 2008;13(3):361–372. doi: 10.1007/s10459-006-9049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dee, T., & Gershenson, S. (2017). Unconscious Bias in the Classroom: Evidence and Opportunities. 2017.

- 26.Knowles MS, Holton EF, III, Swanson RA. The adult learner: the definitive classic in adult education and human resource development. Sixth: Elsevier; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Te Tsuei SH, Lee D, Ho C, Regehr G, Nimmon L. Exploring the construct of psychological safety in medical education. Acad Med. 2019;94(11):S28–S35. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Argyris C, Schön D. What is an organization that it may learn?, in Organizational learning II: theory, method, and practice. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley; 1992. pp. 3–29. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grenny J. The best teams hold themselves accountable. Harv Bus Rev. 2014;1–4.

- 30.Nawaz S. How to create executive team norms — and make them stick. Harv Bus Rev. 2018;1–5.

- 31.Michaelsen LK. Getting started with team-based learning. In: Michaelsen LK, Knight AB, Fink LD, editors. Team-based learning: a transformative use of small groups. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2002. pp. 27–52. [Google Scholar]