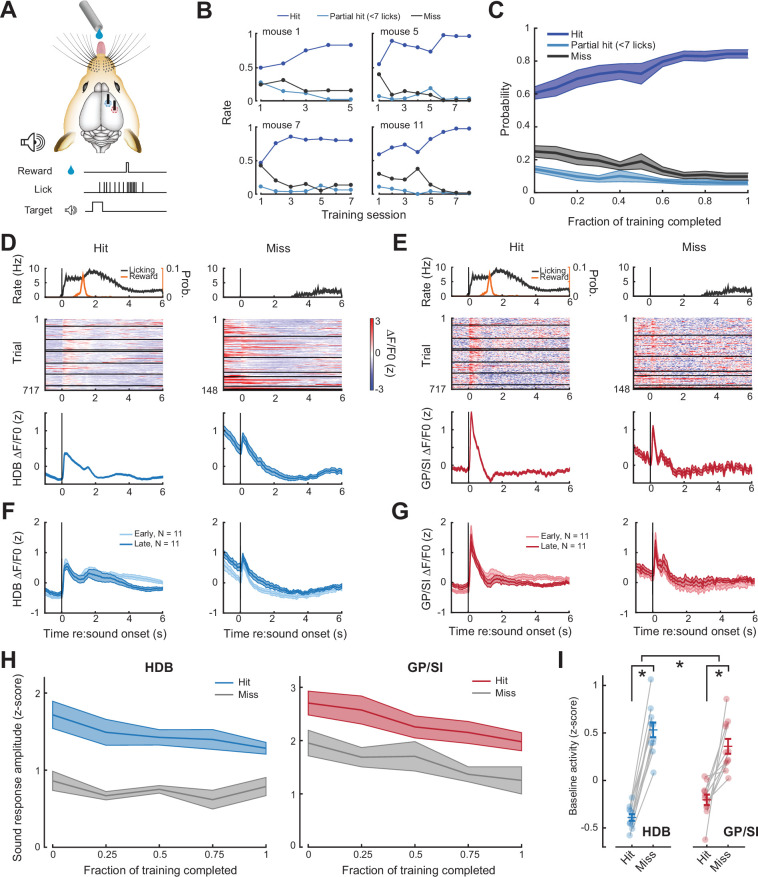

Figure 3. Pre-stimulus cholinergic basal forebrain activity distinguishes behavioral hit and miss trials during an auditory detection task.

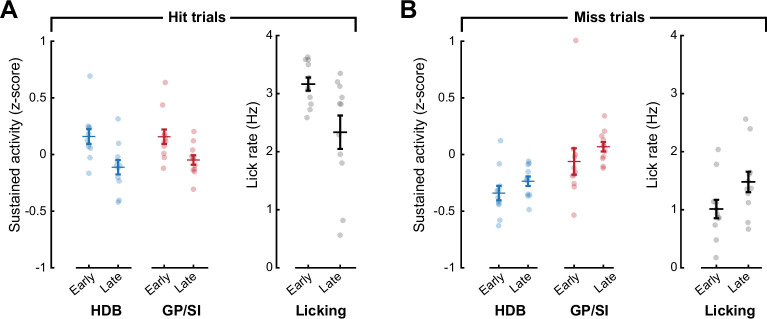

(A) Mice were rewarded for producing a vigorous bout of licking (at least 7 licks in 2.8 s) shortly after a low-, mid-, or high-frequency tone. (B) Learning curves from four example mice that became competent in the detection task at slightly different rates. (C) Mean ± SEM probability of hit, partial hit, and miss trial outcome as fraction of training completed in N = 11 mice. (D–E) Tone-evoked cholinergic GCaMP responses from the horizontal limb of the diagonal band of Broca (HDB) (D) and globus pallidus and substantia innominata (GP/SI) (E) of a single mouse from 717 hit and 148 miss trials distributed over eight appetitive conditioning sessions. Left columns present the timing of lickspout activity, reward probability, heatmaps single trial fractional change values, and mean ± SEM fractional change values. Right columns present the same data on miss trials. Horizontal black lines in heatmaps denote different daily recording sessions. Vertical lines denote tone onset. (F–G) Plotting conventions match D–E, except that data are averaged across all mice (N = 11) and the first third of training trials (early) are plotted separately from the last third of training trials (late). Training-related changes in the sensory-evoked responses were not observed, though see Figure 3—figure supplement 1 for an analysis of small differences in the sustained response. (H) Mean ± SEM sound-evoked response amplitudes in all 11 mice were calculated by subtracting the mean activity during a 2 s pre-stimulus baseline period from the peak of activity within 400 ms of sound onset. Each behavior session was assigned to one of five different discrete time bins according to the fraction of total training completed. Although sound-evoked responses are reduced on miss trials compared to hit trials, they remain relatively stable across all conditions as mice learn to associate neutral sounds with reward (three-way repeated measures ANOVA with training time, trial type, and structure as independent variables: main effect for training time, F = 2.46, p = 0.08; main effect for trial type, F = 14.74, p = 0.012; training time × trial type × structure interaction, F = 0.56, p = 0.7). (I) Mean baseline activity during a 1 s period preceding stimulus onset on hit and miss trials. Circles denote individual mice (N = 11 for all conditions), bars denote sample mean and SEM. Pre-stimulus baseline activity was significantly higher on miss trials than hit trials, particularly in HDB (two-way repeated measures ANOVA with trial type and structure as independent variables: main effect for trial type, F = 102.04, p = 1 × 10–6; trial type× structure interaction, F = 7.89, p = 0.02). Asterisks denote significant differences based on within-structure post hoc pairwise contrasts (p < 0.001 for both) or the trial type × structure interaction term (p = 0.2).