Abstract

Objectives: Chlorhexidine digluconate (chlorhexidine) and Listerine® mouthwashes are being promoted as alternative treatment options to prevent the emergence of antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. We performed in vitro challenge experiments to assess induction and evolution of resistance to these two mouthwashes and potential cross-resistance to other antimicrobials.

Methods: A customized morbidostat was used to subject N. gonorrhoeae reference strain WHO-F to dynamically sustained Listerine® or chlorhexidine pressure for 18 days and 40 days, respectively. Cultures were sampled twice a week and minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of Listerine®, chlorhexidine, ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin, cefixime and azithromycin were determined using the agar dilution method. Isolates with an increased MIC for Listerine® or chlorhexidine were subjected to whole genome sequencing to track the evolution of resistance.

Results: We were unable to increase MICs for Listerine®. Three out of five cultures developed a 10-fold increase in chlorhexidine MIC within 40 days compared to baseline (from 2 to 20 mg/L). Increases in chlorhexidine MIC were positively associated with increases in the MICs of azithromycin and ciprofloxacin. Low-to-higher-level chlorhexidine resistance (2–20 mg/L) was associated with mutations in NorM. Higher-level resistance (20 mg/L) was temporally associated with mutations upstream of the MtrCDE efflux pump repressor (mtrR) and the mlaA gene, part of the maintenance of lipid asymmetry (Mla) system.

Conclusion: Exposure to sub-lethal chlorhexidine concentrations may not only enhance resistance to chlorhexidine itself but also cross-resistance to other antibiotics in N. gonorrhoeae. This raises concern regarding the widespread use of chlorhexidine as an oral antiseptic, for example in the field of dentistry.

Keywords: Neisseria gonnorhoeae, antimicrobial resistance, mouthwash, Listerine®, chlorhexidine, cross-resistance

Introduction

The ongoing emergence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in Neisseria gonorrhoeae has motivated research into antibiotic-sparing treatment options to treat this pathogen (Chow et al., 2021; Van Dijck et al., 2021b). These have included the use of antiseptic mouthwashes to prevent and treat oropharyngeal infection with N. gonorrhoeae (Chow et al., 2017, 2020, 2021; Van Dijck et al., 2021a,b). The oropharynx is thought to play an important role in both the transmission of N. gonorrhoeae and the acquisition of AMR (Lewis, 2015). This is related to a number of factors, including poor antimicrobial penetration and horizontal gene transfer of AMR from commensal Neisseria at this site (Lewis, 2015; Fiore et al., 2020).

Two mouthwashes have been evaluated in clinical and in vitro studies thus far – Listerine® and chlorhexidine digluconate. Listerine Cool Mint® (henceforth termed Listerine®) is a bactericidal mouthwash containing three essential oils [eucalyptol (0.092%); menthol (0.042%) and thymol (0.064%)], methyl salicylate (0.060%) and ethanol (21.6%) (Supplementary Material 1). It exerts its bactericidal effect via a number of pathways, including disruption of the cytoplasmic membranes (Faleiro, 2011; Nazzaro et al., 2013). In vitro, Listerine® was effective against N. gonorrhoeae and in a clinical trial, a single Listerine® mouthwash and gargle reduced pharyngeal culture positivity by 84% (Chow et al., 2017). Results from subsequent studies suggest that this effect is transient. Two large randomized controlled trials have found that the regular use of Listerine® in men having sex with men does not reduce the incidence of N. gonorrhoeae or other STIs (Chow et al., 2021; Van Dijck et al., 2021b). Resistance to essential oils has been reported in several bacteria but never in N. gonorrhoeae. In Staphylococcus aureus, resistance to Melaleuca alternifolia (tea tree oil) has been detected (Nelson, 2000). After exposure to sub-inhibitory concentrations of the essential oils Leptospermum scoparium (manuka), Origanum majorana (marjoram) and Origanum vulgare (oregano), S. aureus acquired resistance to a wide range of antibiotics including ampicillin, erythromycin, neomycin and sulfamethoxazole (Turchi et al., 2019). In Salmonella senftenberg, exposure to the basil oil component, linalool, resulted in adaptation to the basil oil mixture, as well as cross resistance to the antibiotics trimethoprim, sulfamethoxazole, chloramphenicol and tetracycline - increasing their MICs by 2- to 32- fold (Kalily et al., 2017). At least one group of authors have claimed that Listerine does not induce resistance to essential oils but provided little experimental evidence to back this claim up (Hughes and Dean, 2016).

Chlorhexidine digluconate (henceforth termed chlorhexidine) is widely regarded as the gold standard oral antiseptic (Balagopal and Arjunkumar, 2013). Its antibacterial mechanism of action is based on damaging the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane and subsequent leakage of cytoplasmic components (Cieplik et al., 2019). In vitro studies have established that N. gonorrhoeae is highly susceptible to killing by chlorhexidine (Rabe and Hillier, 2000; Victoria et al., 2018; Van Dijck et al., 2020). However, a recent clinical trial was ended early since twice daily gargling with chlorhexidine for six days failed to eradicate N. gonorrhoeae in the oropharynx (Van Dijck et al., 2021a).

To the best of our knowledge, decreased susceptibility to chlorhexidine has never been reported in N. gonorrhoeae before. It has, however, been reported in several other bacteria including Enterobacter spp., Pseudomonas spp., Proteus spp., Providencia spp., Enterococcus spp., and an array of oral bacterial species (Emilson and Fornell, 1976; Wade and Addy, 1989; Kampf, 2016; Kitagawa et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2017). One of the mechanisms responsible for chlorhexidine resistance is alteration of bacterial cell membranes (Kampf, 2018; Cieplik et al., 2019).

For example, in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and P. stutzeri, alterations in the outer membrane and lipopolysaccharide profiles can act as a barrier to prevent chlorhexidine from entering the cell (Tattawasart et al., 2000; Guérin-Méchin et al., 2004). Upregulation of efflux pumps has also been found to confer resistance to chlorhexidine. For example, upregulation of the resistance-nodulation-division (RND) efflux protein, AdeABC, resulted in reduced chlorhexidine susceptibility in Acinetobacter baumannii and Escherichia coli (Hassan et al., 2013; Kampf, 2018; Cieplik et al., 2019). Upregulation of RND pumps results in resistance to a number of clinically important bacteria-antimicrobial combinations (Maris, 1991; Knapp et al., 2013; Fernández-Cuenca et al., 2015). In Klebsiella pneumoniae, for example, exposure to chlorhexidine led to resistance to the last-resort antibiotic, colistin, mediated by the major facilitator superfamily (MFS) efflux pump gene (Wand et al., 2017).

The use of antiseptic mouthwashes remains widespread (Walker et al., 2016). A representative sample of residents in the Grampian region of Scotland, for example, found that 62% reported using mouthwash, and 25.1% did so daily (Macfarlane et al., 2010). These considerations provided the motivation for the current study where we assessed if resistance to chlorhexidine and Listerine® could be induced in N. gonorrhoeae. We also evaluated if these antiseptics could induce cross-resistance to important antibiotics. Currently, N. gonorrhoeae infection is treated with ceftriaxone mono therapy, or dual therapy with ceftriaxone and azithromycin (Cyr et al., 2020; Unemo et al., 2020). An important alternative potential treatment option, when susceptibility has been confirmed, is ciprofloxacin (Klausner et al., 2021).

Materials and Methods

Experimental Procedures

We exposed N. gonorrhoeae reference strain WHO-F to increasing concentrations of Listerine Cool Mint® (Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, NH, United States) and Corsodyl containing chlorhexidine (Supplementary Material 1) using a continuous-culture device known as a morbidostat (Toprak et al., 2013; Verhoeven et al., 2019). According to the EUCAST (v11.0) breakpoints for antimicrobial susceptibility, WHO-F is susceptible to azithromycin, cefixime, ceftriaxone and ciprofloxacin with minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of 0.125, <0.016, <0.002, and 0.004 mg/L, respectively1 (Unemo et al., 2016).

The morbidostat was built following the detailed instructions by Toprak et al., modified for N. gonorrhoeae according to Toprak et al. (2013), Verhoeven et al. (2019). The experiment was carried out exactly as previously reported in the context of a N. gonorrhoeae morbidostat experiment selecting for azithromycin resistance in our laboratory (Laumen et al., 2021). In brief, N. gonorrhoeae cultures were put under sustained Listerine® (n = 6) and chlorhexidine pressure (n = 5), whereas two negative control cultures where exclusively exposed to gonococcal (GC) broth supplemented with 1% IsoVitaleX (BD BBLTM) and vancomycin, colistin, nystatin and trimethoprim selective supplement (VCNT), hereafter called GC medium. GC broth contained per liter, 15 g of proteose peptone 3 (Carl Roth, Karlsruhe), 1 g of soluble starch, 4 g of K2HPO4, 1 g of KH2PO4 and 5 g of NaCl supplemented with 1% IsoVitaleX (BBL). The initial concentrations used in these experiments were based on early in vitro experiments whereby the growth of N. gonorrhoeae was investigated after 60 min of exposure to ten-fold dilutions of the mouthwashes. The highest mouthwash concentration that resulted in a lawn of N. gonorrhoeae growth after inoculation, comparable to the control plate where no mouthwash was added, was used as a starting dilution of the mouthwash.

The initial chlorhexidine concentration used was 0.2 mg/L and was increased twice weekly until a concentration of 80 mg/L was attained in the morbidostat reservoir. The Listerine® concentration was increased in steps from a 100-fold to two-fold dilution. The antiseptics were diluted in GC medium.

Sampling and Agar Dilution

Twice a week, culture suspensions were inoculated on blood agar plates and incubated for 24 h at 36.5°C and 5-7% CO2. Cultures were checked for purity and transferred in 1 mL of skim milk supplemented with 20% glycerol and stored at –80°C. Once the morbidostat experiment was terminated, stored samples were cultured, a single colony was taken and used for MIC determination and whole genome sequencing.

Minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined using agar dilution for Listerine®, chlorhexidine, azithromycin, cefixime, ceftriaxone and ciprofloxacin according to the guidelines of CLSI (Wayne, 2020). Isolates with an increase in MIC for Listerine® or chlorhexidine were subjected to WGS, as were an isolate from the previous, first and last sampling occasion of the same morbidostat culture.

Spearman’s correlation was used to determine the correlation between the MIC of each mouthwash and the MIC of azithromycin, cefixime, ceftriaxone and ciprofloxacin. Only the first sampling timepoint and each timepoint the MICs of the mouthwashes increased were included for this analysis.

Whole Genome Sequencing and Analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated using MasterPure complete DNA and RNA purification kit (Epicenter, United States) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA concentration was assessed using the Qubit ds DNA HS Assay Kit in a Qubit Fluorometer 3.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States). Whole genome sequencing of clones was performed via 2 × 250 bp paired end sequencing (Nextera XT sample) preparation kit and Miseq, Illumina Inc United States.

Genetic changes facilitated by the mouthwashes were explored by comparing whole genome sequences against the reference genome.

Reads were mapped against the reference WHO-F (NZ_LT591897) and variants were extracted using the CLC Genomics Workbench v20 (CLC Bio, Cambridge, MA, United States). Variants were manually examined to establish true variants, which were consequently confirmed by de novo assemblies. In short, Shovill (v1.0.4) (Seemann, 2019) was used for assembly which uses SPAdes (v3.14.0) (Prjibelski et al., 2020) with the following parameters: –trim–depth 150–opts “–cov-cutoff auto –careful.” The quality of the contigs were verified with Quast (v5.0.2) (Gurevich et al., 2013) followed by annotation using Prokka (v1.14.6) (Seemann, 2014). All the sequences generated in this study were submitted to Bioproject PRJNA756860.

Results

Phenotypic Susceptibility Assessment of Neisseria gonorrhoeae Isolates Following Listerine® Exposure

All six cultures exposed to Listerine® lost viability within 18 days after the start of the experiment. This occurred right after the Listerine® concentration in the reservoir was increased from a 5-fold to a 2-fold dilution. The Listerine® MICs did not increase during the course of the experiment (Supplementary Material 2).

Phenotypic Susceptibility Assessment of Neisseria gonorrhoeae Isolates Following Chlorhexidine Exposure

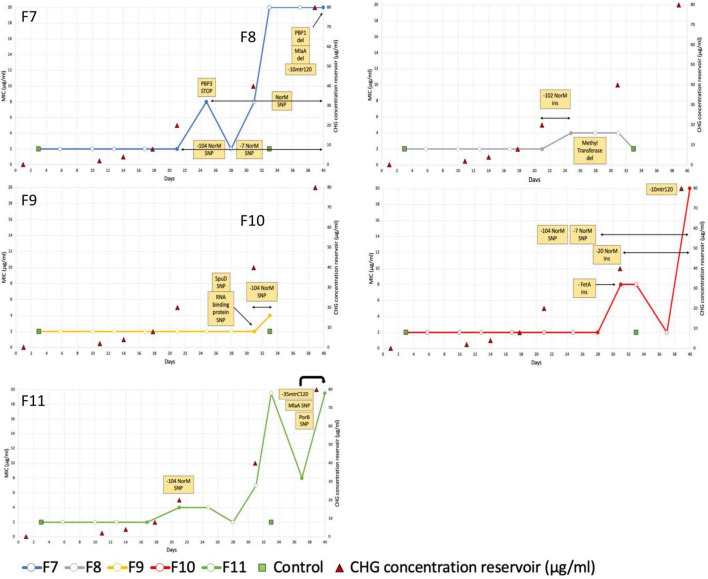

For the five cultures under chlorhexidine selection pressure, MICs of three cultures increased 10-fold (From 2 mg/L at baseline to 20 mg/L after 40 days of exposure) (Figure 1: F7, F10 and F11). For two other cultures, F8 and F9, exposure to GC medium with a chlorhexidine concentration of 20 mg/L added from day 21 revealed initial decreased growth (data not shown) and subsequent no growth after 37 days. The MICs of these cultures increased 4-fold from 2 to 8 mg/L (Figure 1: F8 and F9). The MICs of the two negative control cultures remained 2 mg/L.

FIGURE 1.

Minimal Inhibitory Concentration of 5 Neisseria gonorrhoeae WHO-F cultures under chlorhexidine selection pressure over time. Filled circles depict the timepoints that were sequenced. Variants observed in WGS data are indicated in the yellow boxes. Based on these data, the duration of their detection is depicted via black arrows.

The MICs of azithromycin, cefixime, ceftriaxone and ciprofloxacin increased from 0.125, 0.002, <0.001 and 0.004 mg/L to 0.5, 0.004, 0.002 and 0.06 mg/L, respectively (Supplementary Material 2). The MICs of azithromycin and ciprofloxacin correlated positively with the chlorhexidine MIC: rs = 0.743 (p = 0.003); rs = 0.620 (p = 0.018), respectively.

Whole-Genome Sequencing Analysis of Chlorhexidine-Adapted Strains

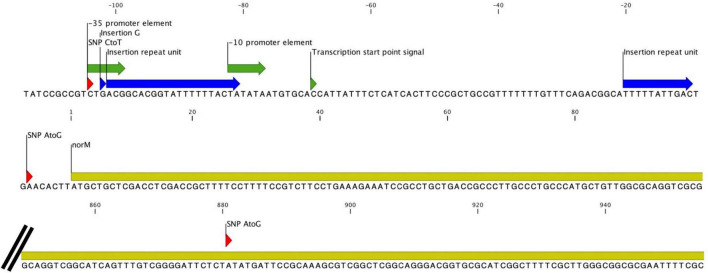

All five cultures developed variants in the gene encoding the multidrug efflux MATE transporter NorM (Figure 1 and Table 1). In total, six different variants were observed related to the norM gene: a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), a one base pair (bp) insertion and a 22-bp repeat unit within the putative –35 promoter element IV, a SNP and a 11-bp repeat unit at the putative ribosome binding site (RBS) and a SNP in the coding region (Figures 1, 2 and Table 1). In all except one culture (F8), a SNP in the putative –35 promoter element was observed, and in most cases this SNP arose at the timepoint before the MIC started to increase and remained present when a MIC of 20 mg/L was reached (Figure 1; F7, F10 and F11). In two of these cultures, F7 and F10, an additional SNP at the RBS was observed at the same timepoints. Once the MIC increased to 8 and 20 mg/L, either the repeat insertion at the RBS or the SNP in the NorM encoding region occurred.

TABLE 1.

Variants occurring in at least 2 cultures of N.gonorrhoeae strain WHO-F exposed to chlorhexidine in the morbidostat set-up.

| Locus tag | Variants in WHO-F cultures by vial number | |||||

| Gene | WHO-F NZ_LT591897 | F7 | F8 | F9 | F10 | F11 |

| 5′ UTR mtrR | C7S05_RS08275 | G131A*(Ohneck et al., 2011) | G131A* | delA57*(Hagman and Shafer, 1995) | ||

| (5′ UTR) norM | C7S05_RS02320 | C104T*(Rouquette-Loughlin et al., 2003), Tyr294Cys, A7G*(Rouquette-Loughlin et al., 2003) | Ins(GACGGCAC GGTATTTTTTA aCTA)102* | C104T* | C104T*, A7G*, insTTTTTATTG AC20* | C104T* |

| mlaA | C7S05_RS13185 | Asn122del | Pro144Ser | |||

Ins: insertion del: deletion UTR: Untranslated Region.

* Indicates the number of base pairs upstream of the translated region. Variants located within the UTR are described as nucleotide changes, variants in the translated region are described as amino acid changes. The numbers in superscript are references to previous studies that have found these same mutations in N. gonorrhoeae.

FIGURE 2.

All variants observed in the norM gene and its promoter. Insertions are indicated in blue while SNPs are indicated in red. The coding region of the gene is colored yellow, and the promoter elements are green.

All isolates with a MIC of 20 mg/L (10-fold increase compared to baseline), carried variants in the promoter of the MtrCDE multidrug efflux pump (Figure 1 and Table 1). In cultures F7 and F10, a C-to-T transition mutation 120 bp upstream of the mtrC start codon (mtr120) was observed, resulting in a consensus –10 element generating a novel promoter for MtrCDE transcription (Ohneck et al., 2011). Culture F11 acquired a single base pair deletion within the 13-bp inverted repeat sequence in the promoter of the MtrCDE repressor MtrR (Hagman and Shafer, 1995).

In addition, variants in the mlaA gene, part of the maintenance of lipid asymmetry (Mla) system were found in two of the three isolates with a MIC of 20 mg/L (Figure 1 and Table 1). In culture F7, asparagine at position 122 was deleted whilst in culture F11 a transition of proline to serine was detected at position 144.

A comprehensive list of all variants detected is provided in Supplementary Material 3. Variants found in only one culture included two penicillin binding proteins (PBP1a and PBP3, culture F7), an outer membrane porin (PorB, culture F11) and protein (FetA, culture F10) and an ABC transporter substrate-binding protein (SpuD, culture F9).

Discussion

We report the first experimental evidence that sustained chlorhexidine exposure can result in reduced susceptibility to chlorhexidine and other antimicrobials in N. gonorrhoeae. In our experiments, the first step in this pathway involved mutations in the gene encoding NorM.

The NorM protein is a Na+-drug antiporter and member of the multidrug and toxic compound extrusion (MATE) family (Kuroda and Tsuchiya, 2009). Two point mutations upstream of the norM gene have previously been reported to result in increased expression of norM and hence decreased gonococcal susceptibility to several cationic compounds and ciprofloxacin (Rouquette-Loughlin et al., 2003; Sánchez-Busó et al., 2021). These two variants were also observed in this current study: a C-to-T mutation in the putative –35 promoter element and an A-to-G mutation 7 bp upstream of the ATG codon resulting in an alteration of the putative RBS. In N. gonorrhoeae strain FA19, these mutations increased the MIC for ciprofloxacin 2 to 4-fold (Rouquette-Loughlin et al., 2003; Golparian et al., 2014). In our experiments, two isolates acquired both mutations in the absence of any other variants. The MIC for ciprofloxacin increased 2-fold in one of these isolates but did not increase in the other isolate. In both cases, the MICs for chlorhexidine remained similar to baseline. Besides other variants (insertion and repeat units) within the putative –35 promoter element and the RBS, one SNP was found in the coding region of norM. The tyrosine to cysteine substitution at position 294 is located at the cation-binding site.

Previous studies have found that sodium ion binding at the cation-binding site causes a conformational rearrangement which in turn leads to the disruption of the protein-drug interactions and triggers the extrusion of the bound drug into the periplasmic space (Lu et al., 2013; Leung et al., 2014). Residue 294 plays an important role in the stabilization of the sodium ion at the binding site, which is crucial for the subsequent drug extrusion stage (Supplementary Material 4) (Leung et al., 2014). Further experimental work will be required to assess the effect of this mutation.

Mutations in the mtrCDE efflux pump were also prominent. In all three cultures that showed a 10-fold increase in chlorhexidine MIC, a variant in the region between the mtrCDE efflux pump and its repressor MtrR was observed. In cultures F7 and F10 (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 1) this was the well-known SNP 120bp upstream of the mtrC start codon, resulting in a consensus –10 element generating a novel promoter for mtrCDE transcription (Warner et al., 2008; Ohneck et al., 2011). In culture F11, a single-base pair deletion in the inverted repeat sequence positioned within the mtrR promoter was found (Hagman and Shafer, 1995). This variant represses transcription of the repressor MtrR and hence enhances expression of mtrC. Since mutations in the MtrCDE efflux pump are well known determinants of resistance to tetracyclines, macrolides and cephalosporins, it is plausible that these mutations are responsible for the observed cross-resistance to these antimicrobial classes in our experiment (Unemo and Shafer, 2014).

Isolates with reduced susceptibility to chlorhexidine possessed mutations in mlaA. Similarly, mutations in the mlaA gene were previously identified in N. gonorrhoeae clones resistant to the quaternary ammonium surfactant dodecyl-prydinium bormide (C12PB) (Calado et al., 2021). The maintenance of lipid asymmetry system (Mla) is responsible for retrograde transport of phospholipids, which is crucial for maintaining and repairing the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, including N. gonorrhoeae (Baarda et al., 2019). The asymmetry of this membrane provides a more effective barrier to toxic lipophilic, hydrophilic and amphipathic molecules than a phospholipid bilayer would be (Baarda et al., 2019). By maintaining the lipid asymmetry of outer membrane, MlaA, may thus play a role in defense against compounds such as chlorhexidine that work by disturbing membrane function. Deletion of the MlaA protein has been shown to disrupt membrane asymmetry and increase susceptibility to antibiotics that target the outer-membrane/cell wall in N. gonorrhoeae (Baarda et al., 2019).

MlaA may also affect chlorhexidine susceptibility via its role in membrane vesicle genesis. Experiments in Porphyromonas gingivalis have found that membrane vesicles could bind to chlorhexidine and thereby protect the bacteria (Grenier et al., 1995). In N. gonorrhoeae, Haemophilus influenzae and Vibrio cholerae, deletion of mlaA has been shown to increase the production of membrane vesicles in vitro (Roier et al., 2016; Baarda et al., 2019). A number of factors such as the availability of iron, presence of human defensins and anatomical site of infection in murines have been shown to influence the expression of mlaA (Baarda et al., 2019). The complexity of this system in addition to the recent emphasis on the role of outer membrane vesicles in antimicrobial resistance in N. gonorrhoeae suggests that further in vivo work will be required to establish the phenotypic effects of the mutations we found in mlaA (Supplementary Material 5) (Unitt et al., 2021).

Previous studies reported similar chlorhexidine MICs in N. gonorrhoeae as in the current study (range 2–8mg/L) (Waitkins and Geary, 1975; Rabe and Hillier, 2000; Victoria et al., 2018). Here, we were able to effect a 10-fold increase in chlorhexidine MIC and concomitant minor increases in azithromycin, ciprofloxacin and cefixime MICs. One of the major limitations of this study is that we have not experimentally confirmed that specific genetic variants result in a particular resistant phenotype. Furthermore, there are important differences in the exposure of N. gonorrhoeae to antiseptic agents between our in vitro model and what might transpire in vivo. The 10-fold increase in chlorhexidine MIC required a long period of exposure (33–40 days) and considerably lower concentrations of chlorhexidine (highest concentration 80 mg/L), than those used in clinical practice (typically 2000 mg/L). This important limitation means that our results are best conceptualized as a worst-case scenario. We cannot conclude from our results that even extensive clinical use of chlorhexidine would have an influence on antimicrobial susceptibility. On the other hand, in vivo, chlorhexidine concentrations and substantivity in the oral cavity can be affected by food, drinks, pH, saliva and serum (Waitkins and Geary, 1975; Rabe and Hillier, 2000; Tomás et al., 2010; Abouassi et al., 2014; Cieplik et al., 2019). Furthermore, chlorhexidine is unlikely to penetrate and kill N. gonorrhoeae localized within pharyngeal epithelial cells intracellularly or in crypts (Veien et al., 1976; Lewis, 2015; Chow et al., 2020). Its penetration into biofilms is also likely incomplete (Cieplik et al., 2019). These factors might create concentration gradients of chlorhexidine that could in turn select for resistance. Chlorhexidine may also select for resistance in commensal Neisseria species. This resistance could then be passed on to N. gonorrhoeae via transformation (Spratt et al., 1989; Ameyama et al., 2002). Anticipating worst-case scenarios is vital for species such as N. gonorrhoeae which are at risk of becoming untreatable with antibiotics (Unemo and Shafer, 2014).

Increasing doses of Listerine® did not result in resistance to Listerine® or cross-resistance to antibiotics. Our results suggest that Listerine® may be a better option in this regard than chlorhexidine. One possible explanation for this difference between Listerine® and chlorhexidine is the number of active ingredients – five in Listerine® and one in chlorhexidine (Balagopal and Arjunkumar, 2013; Van Dijck et al., 2021b). Several targets need to be modified to hinder the effect of essential oils, which could reduce the potential of resistance induction (Yap et al., 2014). Overall, there is limited evidence from studies suggesting the spontaneous occurrence of essential oil resistance, and resistance to the combination of essential oils used in Listerine® has never been reported (Yap et al., 2014). Gonococci remained highly susceptible even after prolonged exposure to sub-inhibitory concentrations, while in vivo an even two times higher concentration of Listerine is used than the final bactericidal dilution added in this experiment. A limitation of this study was the use of VCNT, which was added to the medium to prevent contamination (Verhoeven et al., 2019). It may be possible that Listerine® increased the susceptibility of N. gonorrhoeae to VCNT.

If this occurred, it could have impeded the acquisition of mutants that conferred decreased susceptibility to Listerine®.

Although we cannot exclude this possibility, this study suggests that it is unlikely that resistance to Listerine will occur, making it an interesting antiseptic to use as a way to reduce selection pressure for gonococcal AMR (Chow et al., 2021; Van Dijck et al., 2021b). However, two large randomized controlled clinical trials recently showed that Listerine does not significantly reduce the incidence of oropharyngeal N. gonorrhoeae (Chow et al., 2021; Van Dijck et al., 2021b). On the other hand, we found that exposure to sub-lethal chlorhexidine concentrations may not only enhance resistance to chlorhexidine itself but also cross-resistance to other antibiotics. Intense exposure to chlorhexidine may result in resistance associated mutations in N. gonorrhoeae in three different efflux pumps: the MATE, RND and ABC transporters. We identified a number of mutations to assess in populations where the use of chlorhexidine is intense. In ventilated patients for example, chlorhexidine is used up to six times per day for the prevention of pneumonia (Hutchins et al., 2009). Mouthwashes containing chlorhexidine are used for over 40 years in the field of dentistry to treat gingivitis, periodontitis and tooth decay without being aware of the risk of bacterial resistance (Cieplik et al., 2019; Varoni et al., 2021). These results provide a cautionary note about the possible adverse effects of the excessive use of chlorhexidine. It may thus be prudent to restrict chlorhexidine mouthwash use to those indications with clear evidence of benefit.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

IDB, JGEL, and CK conceptualized the study. JGEL, CVD, SA, and BBX generated the laboratory results. JGEL, SSM-B, and TDB verified and analyzed the data. JGEL wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ivo Jansegers and Patrick Nijs (Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp) for their expertise and assistance throughout all the technical aspects of the morbidostat construction.

Footnotes

Funding

This study was supported by institutional funding from the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2021.776909/full#supplementary-material

References

- Abouassi T., Hannig C., Mahncke K., Karygianni L., Wolkewitz M., Hellwig E., et al. (2014). Does human saliva decrease the antimicrobial activity of chlorhexidine against oral bacteria?. BMC Res. Notes 7:711. 10.1186/1756-0500-7-711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ameyama S., Onodera S., Takahata M., Minami S., Maki N., Endo K., et al. (2002). Mosaic-like structure of penicillin-binding protein 2 gene (penA) in clinical isolates of Neisseria gonorrhoeae with reduced susceptibility to cefixime. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46 3744–3749. 10.1128/AAC.46.12.3744-3749.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baarda B. I., Zielke R. A., Le Van A., Jerse A. E., Sikora A. E. (2019). Neisseria gonorrhoeae MlaA influences gonococcal virulence and membrane vesicle production. PLoS Pathog. 15:e1007385. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balagopal S., Arjunkumar R. (2013). Chlorhexidine: the gold standard antiplaque agent. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 5 270–274. [Google Scholar]

- Calado R., Rodrgues J., Vieira O., Vaz W., Gomes J., Nunes A. (2021). Are Quaternary Ammonium Surfactants good prophylactic options for Neisseria gonorrhoeae “superbug”? 31st ECCMID. Paris: ECCMID. [Google Scholar]

- Chow E. P. F., Howden B. P., Walker S., Lee D., Bradshaw C. S., Chen M. Y., et al. (2017). Antiseptic mouthwash against pharyngeal Neisseria gonorrhoeae: a randomised controlled trial and an in vitro study. Sex. Transm. Infect. 93 88–93. 10.1136/sextrans-2016-052753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow E. P. F., Maddaford K., Hocking J. S., Bradshaw C. S., Wigan R., Chen M. Y., et al. (2020). An open-label, parallel-group, randomised controlled trial of antiseptic mouthwash versus antibiotics for oropharyngeal gonorrhoea treatment (OMEGA2). Sci. Rep. 10:19386. 10.1038/s41598-020-76184-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow E. P. F., Williamson D. A., Hocking J. S., Law M. G., Maddaford K., Bradshaw C. S., et al. (2021). Antiseptic mouthwash for gonorrhoea prevention (OMEGA): a randomised, double-blind, parallel-group, multicentre trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 21 647–656. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30704-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cieplik F., Jakubovics N. S., Buchalla W., Maisch T., Hellwig E., Al-Ahmad A. (2019). Resistance toward chlorhexidine in oral bacteria-is there cause for concern?. Front. Microbiol. 10:587. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyr S. S., Barbee L., Workowski K. A., Bachmann L. H., Pham C., Schlanger K., et al. (2020). Update to CDC’s Treatment Guidelines for Gonococcal Infection, 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 69 1911–1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emilson C. G., Fornell J. (1976). Effect of toothbrushing with chlorhexidine gel on salivary microflora, oral hygiene, and caries. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 84 308–319. 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1976.tb00495.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faleiro M. L. (2011). “The mode of antibacterial action of essential oils,” in Science Against Microbial Pathogens: Communicating Current Research and Technological Advances, ed. Mendez-Vilas A. (Badajoz: Formatex Research Center; ), 1143–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Cuenca F., Tomás M., Caballero-Moyano F. J., Bou G., Martínez-Martínez L., Vila J., et al. (2015). Reduced susceptibility to biocides in Acinetobacter baumannii: association with resistance to antimicrobials, epidemiological behaviour, biological cost and effect on the expression of genes encoding porins and efflux pumps. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 70 3222–3229. 10.1093/JAC/DKV262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore M. A., Raisman J. C., Wong N. H., Hudson A. O., Wadsworth C. B. (2020). Exploration of the neisseria resistome reveals resistance mechanisms in commensals that may be acquired by N. Gonorrhoeae through horizontal gene transfer. Antibiotics 9:656. 10.3390/antibiotics9100656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golparian D., Shafer W. M., Ohnishi M., Unemo M. (2014). Importance of multidrug efflux pumps in the antimicrobial resistance property of clinical multidrug-resistant isolates of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58 3556–3559. 10.1128/AAC.00038-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenier D., Bertrand J., Mayrand D. (1995). Porphyromonas gingivalis outer membrane vesicles promote bacterial resistance to chlorhexidine. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 10 319–320. 10.1111/j.1399-302X.1995.tb00161.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guérin-Méchin L., Leveau J. Y., Dubois-Brissonnet F. (2004). Resistance of spheroplasts and whole cells of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to bactericidal activity of various biocides: evidence of the membrane implication. Microbiol. Res. 159 51–57. 10.1016/j.micres.2004.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurevich A., Saveliev V., Vyahhi N., Tesler G. (2013). QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 29 1072–1075. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagman K. E., Shafer W. M. (1995). Transcriptional control of the mtr efflux system of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Bacteriol. 177 4162–4165. 10.1128/jb.177.14.4162-4165.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan K. A., Jackson S. M., Penesyan A., Patching S. G., Tetu S. G., Eijkelkamp B. A., et al. (2013). Transcriptomic and biochemical analyses identify a family of chlorhexidine efflux proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110 20254–20259. 10.1073/pnas.1317052110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes C. V., Dean J. A. (2016). Mechanical and Chemotherapeutic Home Oral Hygiene. 10th Edition. Amsterdam: Elsevier Inc. 10.1016/B978-0-323-28745-6.00007-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins K., Karras G., Erwin J., Sullivan K. L. (2009). Ventilator-associated pneumonia and oral care: a successful quality improvement project. Am. J. Infect. Control 37 590–597. 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalily E., Hollander A., Korin B., Cymerman I., Yaron S. (2017). Adaptation of Salmonella enterica serovar Senftenberg to linalool and its association with antibiotic resistance and environmental persistence. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 83 e03398–16. 10.1128/AEM.03398-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampf G. (2016). Acquired resistance to chlorhexidine – is it time to establish an ‘antiseptic stewardship’ initiative?. J. Hosp. Infect. 94 213–227. 10.1016/j.jhin.2016.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampf G. (2018). Antiseptic Stewardship: Biocide Resistance and Clinical Implications. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa H., Izutani N., Kitagawa R., Maezono H., Yamaguchi M., Imazato S. (2016). Evolution of resistance to cationic biocides in Streptococcus mutans and Enterococcus faecalis. J. Dent. 47 18–22. 10.1016/j.jdent.2016.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klausner J. D., Bristow C. C., Soge O. O., Shahkolahi A., Waymer T., Bolan R. K., et al. (2021). Resistance-Guided Treatment of Gonorrhea: a Prospective Clinical Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 73 298–303. 10.1093/cid/ciaa596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp L., Rushton L., Stapleton H., Sass A., Stewart S., Amezquita A., et al. (2013). The effect of cationic microbicide exposure against Burkholderia cepacia complex (Bcc); the use of Burkholderia lata strain 383 as a model bacterium. J. Appl. Microbiol. 115 1117–1126. 10.1111/jam.12320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda T., Tsuchiya T. (2009). Multidrug efflux transporters in the MATE family. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteom. 1794 763–768. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laumen J. G. E., Manoharan-Basil S. S., Verhoeven E., Abdellati S., De Baetselier I., Crucitti T., et al. (2021). Molecular pathways to high-level azithromycin resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 76 1752–1758. 10.1093/jac/dkab084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung Y. M., Holdbrook D. A., Piggot T. J., Khalid S. (2014). The NorM MATE transporter from N. gonorrhoeae: insights into drug and ion binding from atomistic molecular dynamics simulations. Biophys. J. 107 460–468. 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis D. A. (2015). Will targeting oropharyngeal gonorrhoea delay the further emergence of drug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains?. Sex. Transm. Infect. 91 234–237. 10.1136/sextrans-2014-051731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M., Symersky J., Radchenko M., Koide A., Guo Y., Nie R., et al. (2013). Structures of a Na+-coupled, substrate-bound MATE multidrug transporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110 2099–2104. 10.1073/pnas.1219901110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlane T. V., Kawecki M. M., Cunningham C., Bovaird I., Morgan R., Rhodes K., et al. (2010). Mouthwash Use in General Population: results from Adult Dental Health Survey in grampian, Scotland. J. Oral Maxillofac. Res. 1:e2. 10.5037/jomr.2010.1402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maris P. (1991). Resistance of 700 gram-negative bacterial strains to antiseptics and antibiotics. Ann. Rech. Vet. 22 11–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazzaro F., Fratianni F., De Martino L., Coppola R., De Feo V. (2013). Effect of essential oils on pathogenic bacteria. Pharmaceuticals 6 1451–1474. 10.3390/ph6121451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson R. R. S. (2000). Selection of resistance to the essential oil of Melaleuca alternifolia in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 45 549–550. 10.1093/jac/45.4.549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohneck E. A., Zalucki Y. M., Johnson P. J. T., Dhulipala V., Golparian D., Unemo M., et al. (2011). A novel mechanism of high-level, broad-spectrum antibiotic resistance caused by a single base pair change in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. mBio 2 e00187–11. 10.1128/mBio.00187-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prjibelski A., Antipov D., Meleshko D., Lapidus A., Korobeynikov A. (2020). Using SPAdes De Novo Assembler. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics 70 1–29. 10.1002/cpbi.102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabe L. K., Hillier S. L. (2000). Effect of chlorhexidine on genital microflora, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Trichomonas vaginalis in vitro. Sex. Transm. Dis. 27 74–78. 10.1097/00007435-200002000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roier S., Zingl F. G., Cakar F., Durakovic S., Kohl P., Eichmann T. O., et al. (2016). A novel mechanism for the biogenesis of outer membrane vesicles in Gram-negative bacteria. Nat. Commun. 7:10515. 10.1038/ncomms10515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouquette-Loughlin C., Dunham S. A., Kuhn M., Balthazar J. T., Shafer W. M. (2003). The NorM efflux pump of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis recognizes antimicrobial cationic compounds. J. Bacteriol. 185 1101–1106. 10.1128/JB.185.3.1101-1106.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Busó L., Yeats C. A., Taylor B., Goater R. J., Underwood A., Abudahab K., et al. (2021). A community-driven resource for genomic epidemiology and antimicrobial resistance prediction of Neisseria gonorrhoeae at Pathogenwatch. Genome Med. 13:61. 10.1186/s13073-021-00858-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seemann T. (2014). Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30 2068–2069. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seemann T. (2019). Shovill. Github. Available online at: https://github.com/tseemann/shovill (accessed April, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Spratt B. G., Zhang Q. Y., Jones D. M., Hutchison A., Brannigan J. A., Dowson C. G. (1989). Recruitment of a penicillin-binding protein gene from Neisseria flavescens during the emergence of penicillin resistance in Neisseria meningitidis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86 8988–8992. 10.1073/pnas.86.22.8988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tattawasart U., Maillard J. Y., Furr J. R., Russell A. D. (2000). Outer membrane changes in Pseudomonas stutzeri resistant to chlorhexidine diacetate and cetylpyridinium chloride. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 16 233–238. 10.1016/S0924-8579(00)00206-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomás I., Cousido M. C., García-Caballero L., Rubido S., Limeres J., Diz P. (2010). Substantivity of a single chlorhexidine mouthwash on salivary flora: influence of intrinsic and extrinsic factors. J. Dent. 38 541–546. 10.1016/j.jdent.2010.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toprak E., Veres A., Yildiz S., Pedraza J. (2013). Building a morbidostat: an automated continuous-culture device for studying bacterial drug resistance under dynamically sustained drug inhibition. Nat. Protoc. 8 555–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turchi B., Mancini S., Pistelli L., Najar B., Fratini F. (2019). Sub-inhibitory concentration of essential oils induces antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Nat. Prod. Res. 33 1509–1513. 10.1080/14786419.2017.1419237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unemo M., Golparian D., Sánchez-Busó L., Grad Y., Jacobsson S., Ohnishi M., et al. (2016). The novel 2016 WHO Neisseria gonorrhoeae reference strains for global quality assurance of laboratory investigations: phenotypic, genetic and reference genome characterization. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 71 3096–3108. 10.1093/jac/dkw288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unemo M., Ross J. D. C., Serwin A. B., Gomberg M., Cusini M., Jensen J. S. (2020). 2020 European guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of gonorrhoea in adults. Int. J. STD AIDS. 10.1177/0956462420949126 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unemo M., Shafer W. M. (2014). Antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the 21st Century: past, evolution, and future. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 27 587–613. 10.1128/CMR.00010-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unitt A., Rodrigues C., Bray J., Jolley K., Tang C., Maiden M., et al. (2021). Typing Outer Membrane Vesicle Proteins Of Neisseria Gonorrhoeae Provides Insight Into Antimicrobial Resistance. Sex. Transm. Infect. 97:37. 10.1136/sextrans-2021-sti.103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijck C., Kenyon C., Cuylaerts V., Sollie P., Spychala A., De Baetselier I., et al. (2020). The development of mouthwashes without anti-gonococcal activity for controlled clinical trials: an in vitro study. F1000Res. 8:1620. 10.12688/f1000research.20399.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijck C., Tsoumanis A., Rotsaert A., Vuylsteke B., Van den Bossche D., Paeleman E., et al. (2021b). Antibacterial mouthwash to prevent sexually transmitted infections in men who have sex with men taking HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PReGo): a randomised, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 21 657–667. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30778-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijck C., Tsoumanis A., De Hondt A., Cuylaerts V., Laumen J., Van Herrewege Y., et al. (2021a). Chlorhexidine mouthwash fails to eradicate oropharyngeal gonorrhea in a clinical pilot trial (MoNg). Sex. Transm. Dis. 10.1097/olq.0000000000001515 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varoni E., Tarce M., Lodi G., Carassi A. (2021). Chlorhexidine (CHX) in dentistry: state of the art. Minerva Stomatol. 61 399–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veien N., From E., Kvorning S. (1976). Microscopy of tonsillar smears and sections in tonsillar gonorrhoea. Acta Otolaryngol. 82:45. 10.3109/00016487609120932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeven E., Abdellati S., Nys P., Laumen J., de Baetselier I., Crucitti T., et al. (2019). Construction and optimization of a ‘NG Morbidostat’ - An automated continuous-culture device for studying the pathways towards antibiotic resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. F1000Res. 8:560. 10.12688/F1000RESEARCH.18861.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victoria M., Kariam K., Mabey D., Stablerm R. (2018). P1856 In vitro activity of chlorhexidine against reference and clinical strains of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. in 28th European congress of clinical microbiology and infectious diseases. Available online at: https://www.escmid.org/escmid_publications/escmid_elibrary/material/?mid=64157 [Google Scholar]

- Wade W. G., Addy M. (1989). In vitro Activity of a Chlorhexidine–Containing Mouthwash Against Subgingival Bacteria. J. Periodontol. 60 521–525. 10.1902/jop.1989.60.9.521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waitkins S. A., Geary I. (1975). Differential susceptibility of type 1 and type 4 gonococci to chlorhexidine (Hibitane). Br. J. Vener. Dis. 51 267–271. 10.1136/sti.51.4.267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker S., Bellhouse C., Fairley C. K., Bilardi J. E., Chow E. P. F. (2016). Pharyngeal gonorrhoea: the willingness of Australian men who have sex with men to change current sexual practices to reduce their risk of transmission- A qualitative study. PLoS One 11:e0164033. 10.1371/journal.pone.0164033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wand M. E., Bock L. J., Bonney L. C., Sutton J. M. (2017). Mechanisms of Increased Resistance to Chlorhexidine and Cross-Resistance to Colistin following Exposure of Klebsiella pneumoniae Clinical Isolates to Chlorhexidine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61 e01162–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Wang H., Ren B., Li H., Weir M. D., Zhou X., et al. (2017). Do quaternary ammonium monomers induce drug resistance in cariogenic, endodontic and periodontal bacterial species?. Dent. Mater. 33 1127–1138. 10.1016/j.dental.2017.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner D. M., Shafer W. M., Jerse A. E. (2008). Clinically relevant mutations that cause derepression of the Neisseria gonorrhoeae MtrC-MtrD-MtrE Efflux pump system confer different levels of antimicrobial resistance and in vivo fitness. Mol. Microbiol. 70 462–478. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06424.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayne P. A. (2020). Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 30th ed, Supplement M100. [Google Scholar]

- Yap P. S. X., Yiap B. C., Ping H. C., Lim S. H. E. (2014). Essential Oils, A New Horizon in Combating Bacterial Antibiotic Resistance. Open Microbiol. J. 8 6–14. 10.2174/1874285801408010006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.