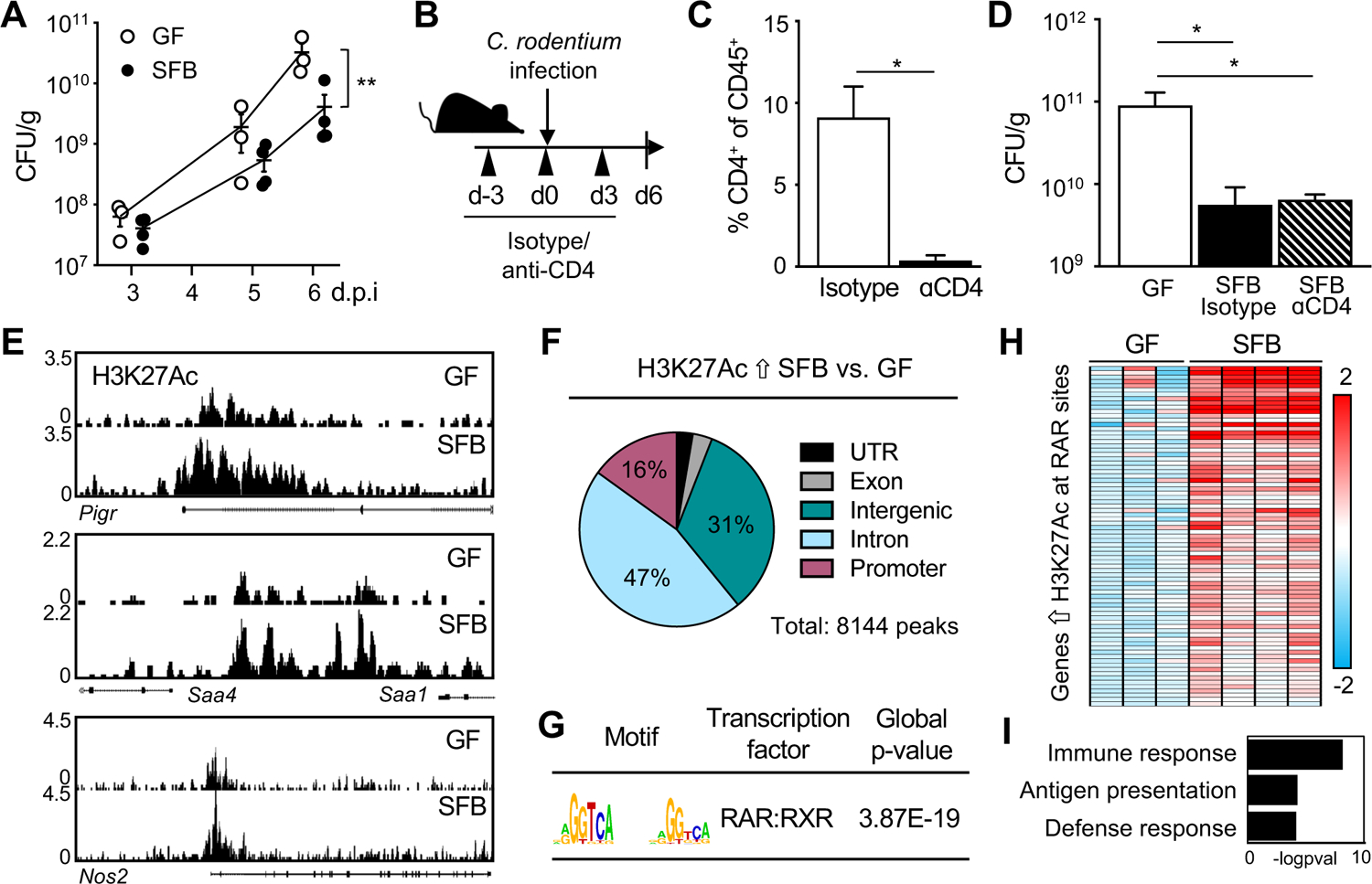

Figure 1: Commensal SFB primes the intestinal epithelium at retinoic acid receptor sites.

(A) Colony-forming units (CFUs) of C. rodentium in stool of infected germ-free (GF) and SFB-monoassociated mice, normalized to sample weight, days 3–6 post-infection (p.i.). (B) Experimental approach. (C) Percent CD4+ T cells in colon from isotype and anti-CD4 treated mice (n = 3). Gated on CD45+ cells. (D) C. rodentium CFUs in stool, normalized to sample weight, day 6 p.i. (n = 3). (E) Representative sequence tracks for H3K27Ac ChIP-seq from IECs isolated from ileum of GF and SFB-monoassociated mice, normalized to reads per million mapped reads. (F) Genomic distribution of H3K27Ac peaks increased in IECs of SFB versus GF mice, shown as percent of total number of differential peaks. (G) Motif enrichment of retinoic acid receptor (RAR) binding elements at SFB-induced H3K27Ac sites using JASPAR. (H) Heatmap of relative mRNA expression in ileal epithelium harvested from C. rodentium-infected GF and SFB mice at day 6 p.i., represented as relative fold change. (I) Gene ontology for RAR targets that are differentially induced in SFB-infected vs GF-infected from (H). Results are mean ± SEM. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. See also Figure S1.