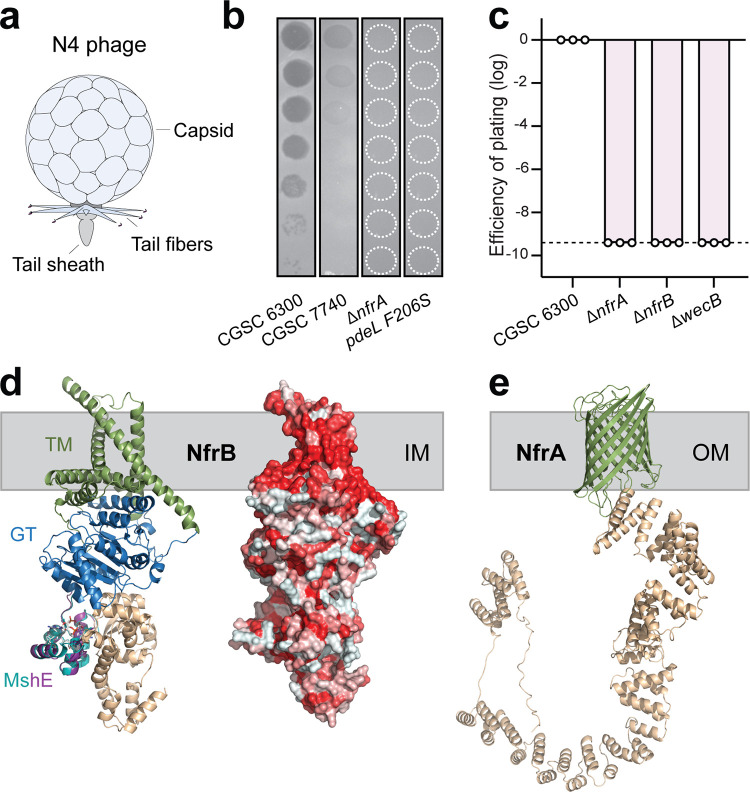

FIG 1.

Infection of E. coli by bacteriophage N4 requires components of a putative surface glycan secretion system. (a) Schematic of bacteriophage N4. (b) Plaque assay with serial 10-fold dilutions of bacteriophage N4 spotted on lawns of different E. coli host strains as indicated. Stippled white circles indicate regions of phage application where no lysis was observed. (c) The efficiency of plating (EOP) is displayed for several E. coli host strains as the number of PFU relative to E. coli wild-type strain CGSC6300. All mutants are in an CGSC 6300 background. Circles indicate the average of two technical replicates of one biological repeat, and the bar indicates the mean of the log-transformed EOP values. The stippled line marks the detection limit. (d) Model of the structure of NfrB as predicted by AlphaFold (30). (Left) Colored domains of NfrB with homology to glycosyltransferases (GT, blue), the c-di-GMP binding domain (cyan, purple), and a domain with unknown function (sand). Putative transmembrane helices (TM) incorporated in the inner membrane (IM) are indicated in green. The putative c-di-GMP binding domain of NfrB (purple) is shown as overlap with the c-di-GMP binding domain of the MshE ATPase from V. cholerae (33) with bound ligand (teal). (Right) Depiction of the NfrB surface with hydrophobic amino acids indicated in red. (e) Structural model of NfrA as predicted by AlphaFold (30). The outer membrane (OM) beta-barrel structure is indicated in green, and the TPR domains and unstructured regions are shown in sand.