Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa senses extracellular heme via an extra cytoplasmic function σ factor that is activated upon interaction of the hemophore holo-HasAp with the HasR receptor. Herein, we show Y75H holo-HasAp interacts with HasR but is unable to release heme for signaling and uptake. To understand this inhibition, we undertook a spectroscopic characterization of Y75H holo-HasAp by resonance Raman (RR), electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR), and X-ray crystallography. The RR spectra are consistent with a mixed six-coordinate high-spin (6cHS), six-coordinate low-spin (6cLS) heme configuration and an H218O exchangeable FeIII–O stretching frequency with 16O/18O and H/D isotope shifts that support a two-body Fe–OH2 oscillator with (iron-hydroxy)-like character as both hydrogen atoms are engaged in short hydrogen bond interactions with protein side chains. Further support comes from the EPR spectrum of Y75H holo-HasAp that shows a LS rhombic signal with ligand-field splitting values intermediate between those of His-hydroxy and bis-His ferric hemes. The crystal structure of Y75H holo-HasAp confirmed the coordinated solvent molecule hydrogen bonded through H75 and H83. The long-range conformational rearrangement of HasAp upon heme binding can still take place in Y75H holo-HasAp, because the intercalation of a hydroxy ligand between the heme iron and H75 allows the variant to reproduce the heme binding pocket observed in wild-type holo-HasAp. However, in the absence of a covalent linkage to the Y75 loop combined with the malleability provided by the bracketing H75 and H83 hydrogen bonds, either the hydroxy sixth ligand remains bound after complexation of Y75H holo-HasAp with HasR or rearrangement and coordination of H85 prevent heme transfer.

Graphical Abstract

Iron is essential for the survival and virulence of nearly all bacterial pathogens. However, in the human body, iron is tightly bound by high-affinity binding proteins such as transferrin and ferritin.1 The innate immune response further limits bioavailable iron by upregulating iron binding proteins such as lipocalin-2 and ferritin.2 To combat iron deficiency within the host, bacterial pathogens have evolved systems that can scavenge iron and heme.3–6 Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a major cause of infection in immune-compromised patients7,8 and encodes several iron uptake systems, including the siderophore-based pyoverdine and pyochelin systems,9,10 the ferrous uptake system (Feo),11 and the heme assimilation (Has) and Pseudomonas heme uptake (Phu) systems.12,13 Within the host, P. aeruginosa senses and alters gene expression in response to the extracellular iron source through cell surface signaling (CSS) systems that encode alternative σ factors. Extra cytoplasmic function (ECF) σ factors are proteins that form a complex with the core RNA polymerase, direct binding to the promoter region of target genes, and activate transcription.14–17 P. aeruginosa encodes several ECF σ factors associated with the iron uptake systems, including iron starvation σ factors PvdS and FpvI. PvdS and FpvI respond to extracellular iron pyoverdine by upregulating expression of the pyoverdine biosynthesis genes and the cognate pyoverdine outer membrane (OM) receptor FpvA, respectively.18–23 Several heme-dependent σ factors associated with heme uptake systems have also been identified in Gram-negative pathogens such as Bordetella pertussis,24 Serratia marcescens,25,26 and P. aeruginosa.12

The P. aeruginosa “Has” system senses heme through the interaction of a secreted extracellular hemophore, HasAp, that captures and releases heme to OM receptor HasR. Capture of the heme by the N-terminal plug domain of HasR results in inactivation of anti-σ factor HasS and release of σ factor HasI. HasI then binds to the hasR promoter, recruits the core RNA polymerase, and upregulates transcription of the has operon. Simultaneously, heme released to HasR is transported through the receptor by the TonB-dependent coupling of the proton motive force of the cytoplasmic membrane. The Has system does not encode a periplasmic transport system, so heme is sequestered and translocated to the cytoplasm by the PhuT-PhuUV periplasmic ABC transport system. Within the cytoplasm, heme is transported to the iron-regulated heme oxygenase (HemO) by cytoplasmic heme binding protein PhuS.27 HemO catalyzes the oxidative cleavage of heme releasing CO, iron, and heme metabolites biliverdin IXβ (BVIXβ) and IXδ (BVIXδ).28 Furthermore, the P. aeruginosa Has and Phu systems have nonredundant roles in heme sensing and uptake, where the Has system is primarily required for sensing, and the Phu system is the major transporter.13 In addition to heme-dependent transcriptional activation of the Has system by σ factor HasI, the hasAp transcript is also subject to post-transcriptional regulation by heme metabolite BVIXβ and/or BVIXδ.29,30 Multiple layers of transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation over the Has system allow the bacteria to rapidly respond to changes in the host environment. The significance of heme sensing and uptake to P. aeruginosa pathogenesis is evident in the fact that clinical isolates from patients with chronic lung infection adapt over time to utilize heme while decreasing pyoverdine biosynthesis.31 Furthermore, in a murine acute lung infection, the has system is the most upregulated set of genes and deletion of the HasR signaling receptor leads to a significant reduction in bacterial load and virulence.32

Given the significance of the Has system to bacterial survival and virulence, we sought to further investigate the molecular mechanism of heme-dependent signaling by the HasAp-HasR complex. Heme in HasAp is coordinated between two loops, one that includes conserved residue Tyr-75 and the other His-32.33 Additionally, Tyr-75 engages in a hydrogen bond with His-83, stabilizing the loop in apo-HasAp and prepositioning Tyr-75 for coordination of the heme iron. Previous spectroscopic and kinetic studies of the HasAp wild-type (WT) protein and the corresponding H32A heme coordination variant concluded heme rapidly binds to the Tyr-75 loop with a slower conformational closure of the His-32 loop.33,34 Similar structural and kinetic studies of the HasAp Y75A and H83A variants concluded that hydrophobic π–π stacking and van der Waals interactions drive heme binding with the axial heme coordination, slowing the release of heme.35 Such a mechanism allows HasAp to capture heme efficiently and with high affinity for delivery to its cognate receptor. In recent studies, we have begun to investigate the role of HasAp axial coordination in the release of heme to HasR by direct analysis of the transcriptional upregulation of the has operon following activation of the ECF σ factor system.29,36 Taken together, our data utilizing WT holo-HasAp and the previously characterized Y75A, H32A, and H83A axial variants are consistent with a model in which holo-HasAp upon interaction with HasR causes a conformational rearrangement disrupting the hydrogen bond between Tyr-75 and His-83 that drives the concerted release of heme to HasR. In these same studies, we observed that a Y75H holo-HasAp variant did not activate the ECF σ factor system and interpreted this to be due to inhibition of the release of heme to HasR. Herein, we further show by surface plasmon resonance (SPR) that the Y75H holo-HasAp protein retains the ability to interact with the HasR receptor but is unable to support heme uptake on supplementation of the P. aeruginosa ΔhasAp strain. Spectroscopic and structural characterization of the Y75H holo-HasAp variant confirmed a similar overall structural fold and heme binding mode to that of WT holo-HasAp. However, rather than the anticipated bis-His ligation, the RR, EPR, and crystal structure are consistent with heme coordination through a water molecule that is strongly hydrogen bonded to H75 and H83. Furthermore, mutation of the Tyr-His motif causes a conformational rearrangement of the H32 loop that is also seen in the Y75A and H83A holo-HasAp crystal structures.35 We propose this strongly hydrogen bonded Fe-OH ligand inhibits the conformational rearrangement required to facilitate heme release.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Proteins.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study were as previously reported.29 Escherichia coli strains were routinely grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (American Bioanalytical) or on LB agar plates, and P. aeruginosa strains were freshly streaked and maintained on Pseudomonas isolation agar (PIA) (BD Biosciences). All strains were stored frozen at −80 °C in LB broth with 20% glycerol. All purified proteins were stored at −80 °C until further use.

Purification of HasAp WT and Y75H Proteins.

Protein expression was performed by a slight modification of the previously published method.29 Briefly, WT and Y75H HasAp were expressed by culturing a single colony from freshly transformed E. coli BL21(DE) cells for 16 h in LB medium (100 mL) containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin at 37 °C while being shaken. The cells were harvested by centrifugation and washed twice in M9, and the cell pellet was resuspended and used to inoculate 4 × 1 L of M9 medium containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin to a final OD600 of 0.05. The cells were grown to an OD600 of ~1.0, induced with a final concentration of isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) of 1 mM, and grown for a further 16 h at 30 °C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and stored at −80 °C until further use. Pellets were thawed and resuspended in 40 mL of lysis buffer [20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 20 mM NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA] containing a protease inhibitor tablet (Roche), 1 mg/mL DNase, and 25 mg/mL lysozyme, stirred at 4 °C for 1 h, and passed through a model LM-20 microfluidizer at 20000 psi. The lysis suspension was centrifuged at 25000 rpm for 1 h, and the supernatant applied to a Q-Sepharose column (3 cm × 10 cm) pre-equilibrated with equilibration buffer [20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and 20 mM NaCl]. The column was washed (3–5 column volumes) with equilibration buffer, and the protein eluted over a gradient from 20 to 600 mM NaCl in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). The purity of the eluted fractions was determined by SDS–PAGE, and the peak fractions were pooled and dialyzed in 4 L of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) containing 50 mM NaCl. The protein was concentrated and further purified on an AKTA FPLC instrument over a 26/60 Superdex 200 size exclusion column. Fractions containing purified protein were pooled, concentrated to 10 mg/mL, and stored at −80 °C. Apo-HasAp was reconstituted with heme prepared immediately prior to use by being dissolved in 0.1 mM NaOH and buffered with 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8). The final concentration of the heme stock was determined by the pyridine hemochrome method.37 WT and Y75H HasAp were reconstituted in a 1:1 ratio with hemin, incubated on ice for 30 min, and concentrated via an Amicon ultracentrifuge filter (30 MWCO). The integrity of protein secondary structure was determined by circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy recorded on a Jasco J-810 spectropolarimeter as previously described.29

Purification and Reconstitution of HasR in SMALPS.

HasR was prepared as previously described.38 Briefly, a single colony of freshly transformed E. coli BL21 (DE3) transformed with pHasR22b was used to inoculate 50 mL of non-inducing MDAG-135 medium containing 100 μg/mL Amp and grown overnight at 37 °C and 225 rpm. This culture was used to inoculate four 1 L flasks of autoinducing MDA-5052 medium containing 100 μg/mL Amp and grown for 10 h at 25 °C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 40 mL of lysis buffer, and passed through a model LM-20 microfluidizer at 20000 psi. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 12000 rpm for 15 min, and the supernatant was centrifuged for 1 h at 25000 rpm to pellet the cellular membranes. Pelleted membranes were resuspended in 30 mL of lysis buffer with an added EDTA-free protease inhibitor tablet (Roche) overnight. The cytoplasmic membrane proteins were solubilized by addition of 2% (v/v) Triton X-100 (Sigma) and 0.5% (v/v) N-lauroylsarcosine sodium salt (Sigma). The membrane fractions were stirred at room temperature for 1 h and pelleted at 25000 rpm for 1 h at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded, and the pelleted OM fraction was resuspended in 30 mL of lysis buffer containing an EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail tablet and stirred at 4 °C overnight.

The RC DC protein assay (Bio-Rad) was used to determine the total protein concentration, and the OM fragments were diluted to a final concentration of ~10 mg/mL. The styrene-maleic acid copolymer (Xiran SL30010 P20) was then added to the OM suspension to a final concentration of 2.5% (v/v) and inverted continuously at room temperature for 1 h. The suspension was frozen in liquid nitrogen and thawed at 42 °C a total of five times followed by passage through a microfluidizer at 20000 psi. This cycle was repeated once more; the final suspension was centrifuged at 25000 rpm for 1 h at 4 °C, and the supernatant containing the HasR in lipid nanodisc (HasR-SMALP) was collected. The supernatant was concentrated, and the HasR concentration was determined using an extinction coefficient of 126 mM−1 cm−1 after subtracting the blank containing the filtrate (to account for absorption of residual lipids and polymer).

Surface Plasmon Resonance of Holo-HasAp WT and Y75H Binding to HasR.

Holo-HasAp WT or Y75H protein was covalently bound to the surface of flow cells 2–4 of a CM5 chip to a final level of 50 RU using the NHS-EDC kit (GE Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ). Flow cell 1 was used as a blank. HasR-his (0–1000 nM) in 120 μL of HBS-EP buffer (GE Life Sciences) was injected into flow cells 1–4 at 25 °C until the signal reached saturation. The surface was then washed with buffer for 3 min, and the dissociation of analyte–ligand complexes was followed over time. The flow cells were regenerated by injecting 15 μL aliquots of 10 mM glycine (pH 1.5) followed by 15 μL aliquots of 10 mM NaOH, and the process was repeated. Values from the reference flow cell were subtracted to obtain the values for specific binding. The maximum response units during the steady-state phase were plotted as a function of HasR concentration, and data were fitted to a 1:1 binding model using BIAeval version 4.1 (Biacore).

[13C]Heme Uptake and Extraction of [13C]BVIX Isomers from Holo-HasAp WT- and Y75H-Supplemented Cultures.

[13C]Heme uptake studies were performed as previously described.36 Briefly, a single isolated colony of the ΔhasAp strain29 was picked, inoculated into 10 mL of LB broth, and grown overnight at 37 °C. The cultures were then harvested and washed in 10 mL of M9 minimal medium (Nalgene). The iron levels in M9 medium were determined by ICP-MS to be <1 nM. Following centrifugation, the bacterial pellet was resuspended in 10 mL of M9 medium and used to inoculate 50 mL of fresh M9 low-iron medium to a starting OD600 of 0.04. Cultures were grown at 37 °C while being shaken for 3 h before the addition of 1 μM WT or Y75H [13C]holo-HasAp. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, and the BVIX isomers were extracted as previously described.30 Briefly, the cell medium was collected and filtered through a Nalgene vacuum filtration unit with a 0.22 μm PVDF membrane. The resulting flow-through was acidified to pH ~2.5 with 10% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), supplemented with a final concentration of BVIXα dimethyl ester of 10 nM as an internal standard and loaded over a C18 Sep-Pak column (Waters). The column was previously flushed with 2 mL of acetonitrile (ACN), H2O, 0.1% TFA in H2O, and methanol in 0.1% TFA (10:90). Following sample application, the columns were washed with 4 mL of 0.1% TFA, 4 mL of an ACN/0.1% TFA mixture (20:80), and 2 mL of a methanol/0.1% TFA mixture (50:50). Purified BVIX isomers were eluted in methanol, dried, and stored for up to 1 week at −80 °C prior to LC-MS/MS analysis.

LC-MS/MS Analysis of BVIX Isomers.

Samples were resuspended in 10 μL of DMSO, diluted to 100 μL with mobile phase ACN [50:50 (v/v)], centrifuged at 14000 rpm for 5 min at room temperature to remove particulates, and filtered through a 0.45 μm syringe filter prior to loading. BVIX isomers (2 μL) were separated and analyzed by LC-tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) (Waters TQ-XS triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer with an AQUITY H-Class UPLC instrument) as previously described with slight modification.30 BVIX isomers were separated on an Ascentis RP-amide 2.7 μm C18 column (10 cm × 2.1 mm) at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min. The mobile phase consisted of phase A (H2O/0.1% formic acid) and phase B (ACN/0.1% formic acid). The initial gradient is 64% A and 36% B. After 5 min, 55% A and 45% B, after 8 min 40% A and 60% B, after 8.5 min 5% A and 95% B, and after 10 min 64% A and 36% B. Fragmentation patterns of the precursor ions were detected at 583.21 ([12C]BVIX) and 591.21 ([13C]BVIX) using multiple-reaction monitoring (MRM). The source temperature was set to 150 °C, the capillary voltage to 3.60 kV, and the cone voltage to 43 V. The column was kept at 30 °C during separation. The precursor ions used in MRM for the α, β, and δ isomers of [12C]BVIX are at 297.1, 343.1, and 402.2, respectively, with collision energies of 38, 36, and 30 V, respectively. The product ions used in MRM for the α, β, and δ isomers of [13C]BVIX are at 301.1, 347.1, and 408.2, respectively, with a collision energy of 34 V for each.

Resonance Raman and EPR Spectroscopy.

All EPR and RR measurements were conducted on solutions containing 150–200 μM heme in 100 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.5). Water exchange with H218O and D2O was performed through concentration and redilution of the protein solution with the HEPES buffer prepared in labeled water to reach labeling levels of >80%. The RR spectra were recorded on a custom McPherson 2061/207 spectrograph equipped with a liquid N2-cooled CCD detector (LN1100PB, Princeton Instruments). The excitation wavelength at 407 nm was provided by a krypton laser (Innova 302C, Coherent) with attenuation of the Rayleigh scattering with a long-pass filter (RazorEdge, Semrock). Room-temperature RR spectra were recorded in a 90° scattering geometry, while RR spectra of frozen solutions maintained at 110 K with a liquid nitrogen coldfinger were recorded using a back-scattering geometry. Comparison of spectra obtained with short acquisition on rapidly spinning samples with longer acquisition on static samples confirmed the lack of photosensitivity of all samples with laser intensities maintained below 15 mW. Frequency calibrations using indene and aspirin standards are accurate with ±1 cm−1.

EPR spectra were recorded on a Bruker E-500 X-band EPR spectrometer equipped with a superX microwave bridge and a dual-mode cavity with a helium flow cryostat (ESR900, Oxford Instruments). The microwave frequency was 9.67 GHz, the microwave power 1 mW, the modulation frequency 100 kHz, and the modulation amplitude 4 G.

Crystallography.

Diffraction quality crystals of the Y75H HasA variant were obtained when the purified enzyme (0.5 μL at 10 mg/mL) was mixed in a 1:1 ratio with a precipitating solution containing 0.1 M sodium chloride, 0.1 M HEPES (pH 7.5), and 1.6 M ammonium sulfate (100 μL reservoir) using a Mosquito (tpplabtech, Boston, MA) protein crystallization robot. Crystals appeared 4 weeks after incubation at 18 °C. Crystals of the H32A HasA variant were obtained when the purified enzyme (1 μL at 10 mg/mL) was mixed in a 1:1 ratio with a precipitating solution of 1 M sodium citrate, 0.1 M Tris (pH 7.0), and 0.2 M sodium chloride. Crystals of HasA H32A were obtained via sitting drop diffusion. Crystals appeared after incubation for 1 week at 18 °C. Monochromatic data collection with 0.97 Å X-rays was performed at SER-CAT on beamline 22-ID at the Advanced Photon Source (Argonne, IL). Data were processed using SGXPRO, and 5% of the reflections were set aside for cross-validation.39 Phases were obtained by molecular replacement using the WT HasAp [Protein Data Bank (PDB) entry 3ELL] model, and initial phasing was performed using PHENIX. Successive rounds of model building and refinement were performed using COOT and PHENIX.40,41 Data collection and refinement statistics are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Data Collection and Refinement Statistics for HasAp Variant Y75H

| data collection | refinement | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| beamline | APS 22-ID | unit cell dimensions | a = 34 Å, b = 47 Å, c = 101 Å, α = β = γ = 90° |

| space group | P212121 | no. of protein atoms | 1385 |

| wavelength | 0.97 | no. of solvent atoms | 170 |

| resolution range (Å) | 50.0–1.32 | resolution limits (Å) | 50.0–1.31 |

| outer shell | 1.39–1.32 | Rcryst (%) | 16.6 |

| no. of unique observations | 48941 | Rfree (%) | 18.8 |

| completeness (%) | 98.5(96.2)a | rmsd for bonds (Å) | 0.006 |

| Rsym (%)b | 7.7(36.5) | rmsd for angles (deg) | 1.593 |

| CC1/2 | 1.0(0.982) | average B factor (Å2) | 11.6 |

| redundancy | 25.8(21.4) | PDB entry | 6U87 |

| I/σ | 52.7(6.8) |

Numbers in parentheses denote values for the outermost resolution shell.

, where Ihkl is the intensity of an individual measurement of the reflection with indices hkl and 〈Ihkl〉 is the mean intensity of that reflection.

RESULTS

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Analysis of Interaction of Holo-HasAp WT and Y75H with HasR.

We previously characterized the heme binding properties of Y75H HasAp along with that of the Y75A, H32A, and H83A variants.29 The heme binding affinity (KD) as determined by isothermal titration calorimetry for Y75H HasAp (1.1 ± 0.7 μM) is identical to that of WT HasAp (1.2 ± 0.8 μM). Whereas binding of heme to WT and Y75H HasAp was enthalpically driven, the Y75A variant showed an increase in entropy at the expense of enthalpic contributions that were attributed to stronger hydrophobic interaction of the heme with the Y75 loop and disorder in the loop upon loss of the coordinating ligand. Moreover, transcriptional reporter assays further showed the heme coordination mutants Y75A, H83A, and H32A holo-HasAp variants retained their ability to activate the ECF σ factor system. However, the holo-HasAp Y75H variant showed no transcriptional activation at the hasR promoter. We initially attributed this to the inability of holo-HasAp Y75H protein to release heme to HasR due to potentially stronger bis-His coordination. We previously determined the relative KD for binding of apo- and holo-HasAp WT to purified HasR WT in SMALPs as the analyte.38 The calculated KD for the binding of holo-HasAp to HasR as determined by steady-state association measurements with various analyte concentrations was 479 ± 20 nM. Herein, we determined the KD for holo-HasAp Y75H to be 394 ± 5 nM (Figure 1). The similar binding affinity of holo-HasAp WT and Y75H protein for HasR ruled out disruption of the protein–protein interaction as the reason for Y75H holo-HasAp’s inability to activate the ECF σ factor system. As transcriptional activation and heme transport require protein–protein interaction, conformational rearrangement, and energy-dependent uptake, any in vitro measurement of binding affinity (KD) merely represents a determination of relative associations of the holo-HasAp and HasR proteins. To further determine if the inability to signal is due to heme retention in Y75H holo-HasAp, we also evaluated heme uptake in vivo utilizing our previously developed [13C]heme uptake assay.

Figure 1.

Steady-state analysis of binding of holo-HasAp Y75H to HasR by SPR. (A) Increasing concentrations of HasR (0–1000 nM) were injected over amine-coupled holo-HasAp Y75H in triplicate. (B) Plot of the response units at equilibrium (Req) vs HasR concentration. The data were fit to a 1:1 binding model using Biacore BIAeval version 4.1. The results represent one of three independent replicates.

[13C]Heme Isotopic Labeling and LC-MS/MS Analysis of the BVIX Isomers.

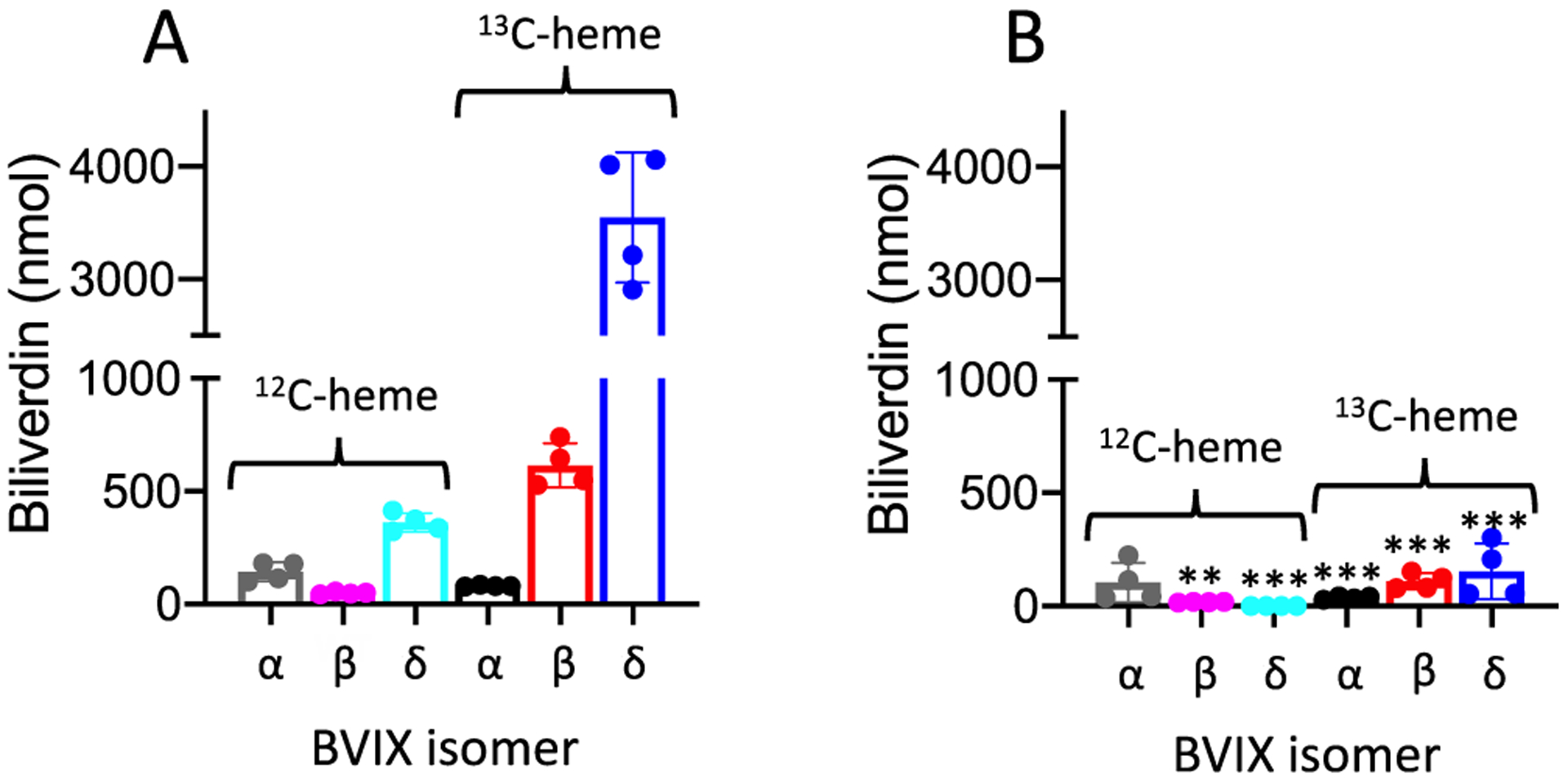

Heme release and transport were assessed by analysis of the BVIX metabolites following supplementation of cultures with either WT or Y75H [13C]heme-HasAp. Supernatants were collected 4 h following supplementation, and the BVIX metabolites extracted and analyzed by LC-MS/MS. We confirmed that PAO1 WT cultures supplemented with [13C]heme-HasAp were able to utilize the heme via the Has system (Figure 2A). The ΔhasAp cultures supplemented with Y75H [13C]heme-HasAp variant were unable to utilize heme as an iron source as judged by the lack of [13C]BVIXβ and BVIXδ metabolites (Figure 2B). This observation is consistent with recent studies of the heme uptake defective hasRH624A and hasRH221R allelic strains where free heme in solution, but not heme bound to HasAp, is accessible to the PhuR transporter.36 The inability of Y75H holo-HasAp to support heme uptake is also consistent with inhibition of heme release to HasR.

Figure 2.

Heme utilization by the ΔhasAp strain supplemented with [13C]holo-HasAp (A) WT or (B) Y75H. LC-MS/MS analysis of the BVIX isomers supplemented with 1 μM [13C]holo-HasAp at 4 h. Biliverdin values represent the standard deviation of four biological replicates. The indicated p values for each strain compared back to PAO1 WT for the respective BVIX isomers were <0.005 (two asterisks) or <0.001 (three asterisks).

Spectroscopic Characterization of the Holo-hasAp Y75H Variant.

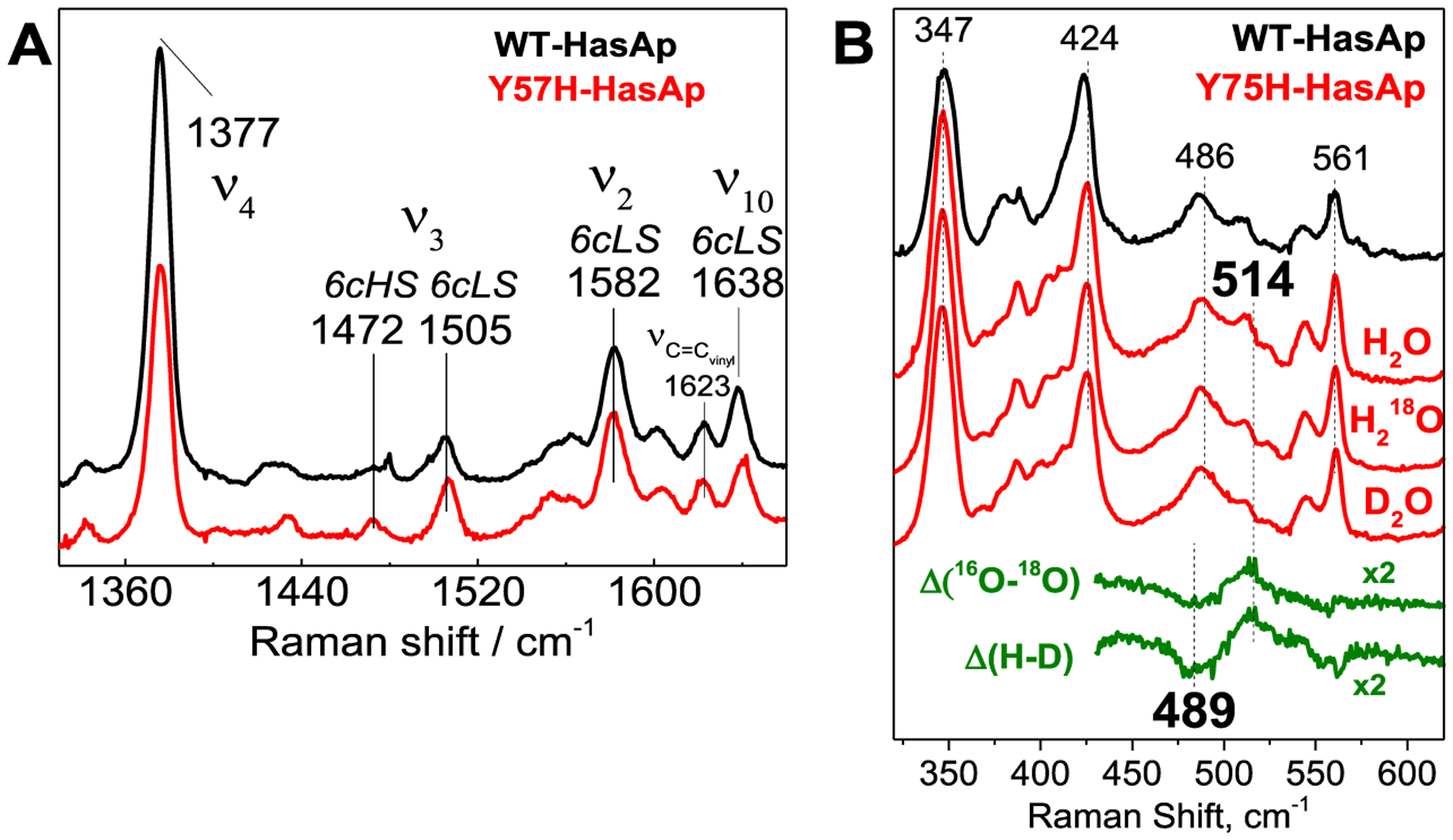

The room-temperature absorption spectra of WT and Y75H holo-HasAp show differences in their high-spin:low-spin ratios as judged by the increased intensity of the Q-bands at 537 and 570 nm and decreased high-spin marker at 618 nm in the holo-HasAp Y75H variant compared to WT (Figure 3A). To further confirm the coordination and the heme iron status of the Y75H holo-HasAp variant, we performed RR spectroscopy. The room-temperature RR spectrum of WT holo-HasAp obtained with Soret excitation shows a porphyrin skeletal frequency ν4 at 1370 cm−1 typical of ferric (Fe3+) hemes and ν3, ν2, and ν10 frequencies representative of both six-coordinate high-spin (6cHS) (1477, 1561, and 1605 cm−1, respectively) and six-coordinate low-spin (6cLS) (1503, 1579, and 1634 cm−1, respectively) conformers (Figure 3B,C). Y75H holo-HasAp shows similar RR frequencies from both 6cHS and 6cLS species compared to WT holo-HasAp, but the high-spin versus low-spin intensities are significantly lower in Y75H than in the WT. The vinyl stretching frequency at 1624 cm−1 and C–C–C deformation modes at 378 and 410–420 cm−1 from the porphyrin peripheral groups are not significantly affected by the Tyr-75 to His substitution, suggesting the heme seating is similar in both proteins. RR spectra of WT and Y75H holo-HasAp at 110 K show greatly decreased intensities for the 6cHS contribution and increased intensities for the 6cLS contribution (Figure 4A). Most importantly, low-frequency RR spectra of Y75H holo-HasAp recorded at 110 K show a ν(FeIII–OH) stretching frequency at 514 cm−1 identified through its downshift after incubation in H218O and D2O (Figure 4B). This low-spin ν(FeIII–OH) frequency is ~40 cm−1 lower than in hydroxy complexes of vertebrate globins in alkaline buffers and is more in tune with frequencies observed in bacterially truncated hemoglobins, where the presence of multiple hydrogen bond interactions with the coordinating hydroxy group weakens the FeIII–OH bond.42

Figure 3.

Room-temperature (A) UV–vis and (B and C) RR spectra of WT and Y75H holo-HasAp. The UV–vis spectra were recorded directly from the Raman capillaries with ~150 μM protein in 100 mM HEPES (pH 7.5).

Figure 4.

Low-temperature RR spectra of WT and Y75H holo-HasAp. The protein concentrations were ~200 μM in 100 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), and the level of H 182O or D2O enrichment is >80%.

While the 25 cm−1 downshift observed with 18O exchange matches reasonably well with the calculated shifts for a two-body Fe–OH harmonic oscillator (Δ18Ocalc = −21 cm−1), the large isotope shift observed with H/D exchange is more puzzling. One possible interpretation for these isotope shifts is that the 514 cm−1 band corresponds to a two-body Fe–OH2 oscillator with both H atoms engaged in short hydrogen bond interactions, leading to an iron(III)-hydroxo-like sixth ligand (Scheme 1). This analysis of the RR data is supported by the crystallography data (see the following section).

Scheme 1.

Proposed Fe–OH2 Oscillator

The EPR spectra of holo-HasAp WT and Y75H are dominated by a rhombic signal centered around g = 2, consistent with the 6cLS ferric heme species (Figure 5A). As previously observed for holo-HasAp WT,34 a minor resonance at g = 6.1 corresponding to an axial high-spin heme population is also present in the holo-HasAp Y75H variant. The holo-HasAp WT 6cLS resonances at g = 2.83, 2.20, and 1.71 are identical to those previously reported.34 In contrast, holo-HasAp Y75H shows broadened resonances at g = 2.89, 2.24, and 1.65. Using McGarvey’s analysis of the tetragonal low-spin d5 ferric heme EPR signature48 and Joshua Tesler’s DLD5 program to calculate ligand-field splitting parameters, we compare holo-HasAp Y75H with other low-spin heme proteins as initially carried out by Blumberg and Peisach.49 The resulting ligand-field splitting values are intermediate between those previously reported for bis-His and His-hydroxy ligated systems (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

(A) EPR spectra (10 K) of WT and Y75H holo-HasAp and (B) correlation of axial and rhombic ligand-field parameters for HasAp low-spin heme complexes as well as representative bis-His and His-hydroxy heme proteins. The protein concentrations were ~200 μM in 100 mM HEPES (pH 7.5). Splitting parameters for Y75H HasAp (this work) and Y75A HasAp35 and for alkaline sperm whale myoglobin (alk. Mb),43 alkaline horseradish peroxidase (alk. HRP),44 liver microsomal cytochrome b5 (b5 and alk. b5),45 mitochondrial cytochrome b2 (cyt b2)46, and horse heart cytochrome c (cyt c).47 Bis-His entries are colored black, and His-hydroxy entries are colored red; the entry for WT HasAp with its His-Tyr axial ligands is colored blue.

Crystal Structure of the Holo-HasAp Y75H Variant.

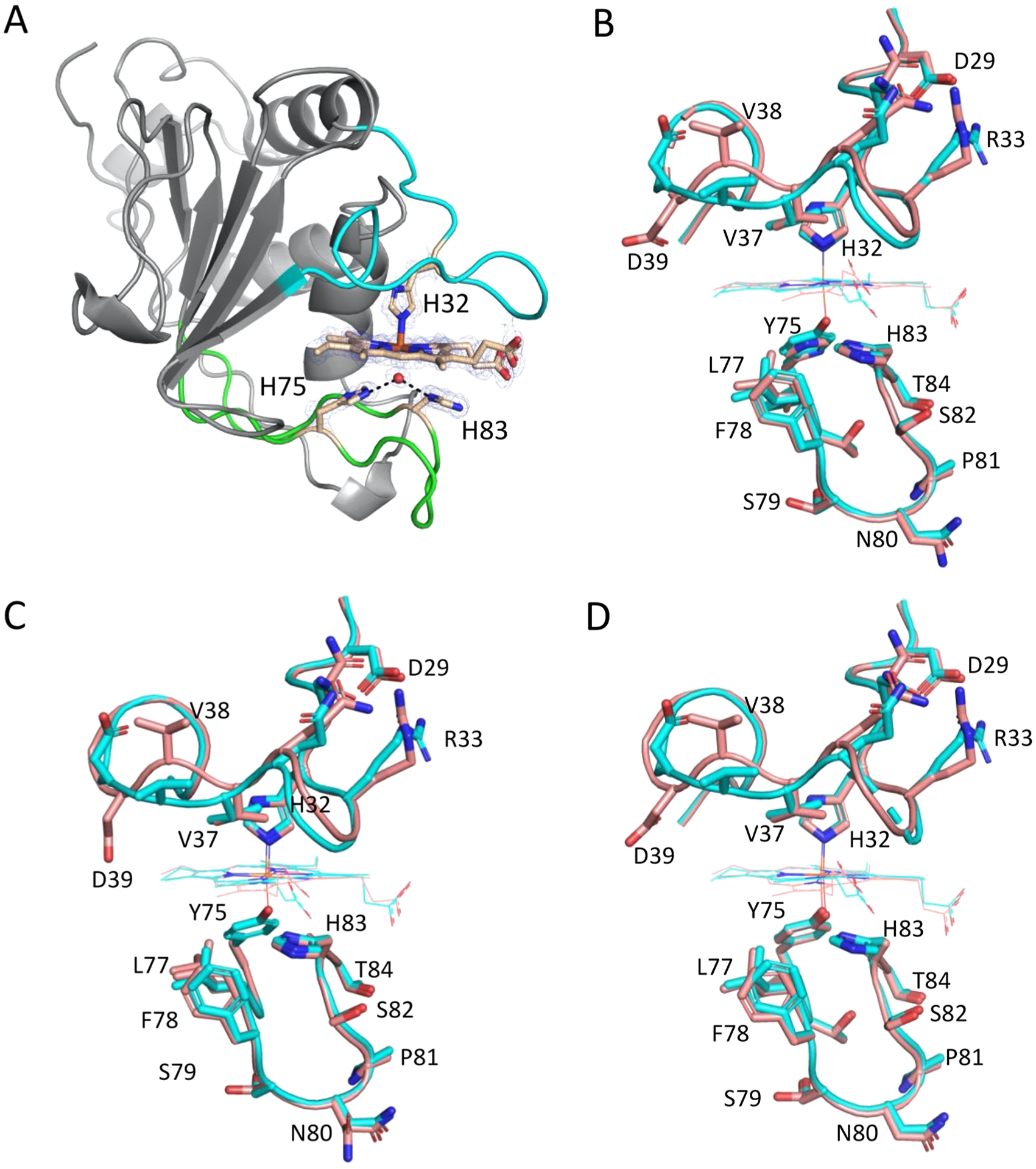

The holo-HasAp Y75H structure, determined to 1.3 Å resolution, shows an overall αβ fold similar to that of holo-HasAp WT (Figure 6A). As for the holo-HasAp WT, the holo-HasAp Y75H structure consists of an extended “β-sheet wall” comprised of eight antiparallel β-strands connected by hairpin loops. Opposite of this “β-sheet wall” four α-helices pack to form a “α-helix wall”. Additionally, the plane of the porphyrin ring for the heme in holo-HasAp Y75H is oriented in a similar manner when compared to that of the WT protein (Figure 6B). The Fe–NHis32 bond lengths in the WT and Y75H mutants are similar at 2.0 and 2.2 Å, respectively. The sixth coordination site of the heme iron is occupied by a solvent molecule in HasAp Y75H with an Fe–O bond length of 2.1 Å that mimics well the 2.0 Å Fe–OTyr75 distance observed in the WT structure (Figure 6B).50 The distance from the His-Nε of H75 or H83 to the iron-bound solvent molecule is 2.5 Å. Interestingly, the Nδ atom of H83 that is located in the loop linking strands β3 and β4 forms a hydrogen bond with the phenol oxygen of Y75 in the apo- and holo-HasAp WT structures.33 On the basis of stopped flow absorption and rapid freeze quench RR of heme binding to the WT, Y75A, and H83A variants, the authors proposed the Tyr75 Oη–His83 Nδ hydrogen bond facilitates heme loading by orienting Y75 to coordinate the heme iron. In the absence of the hydrogen bond in the Y75A variant, the conformational disorder in the loop may allow for transient coordination of H83 prior to loop closure and coordination of H32 that leads to displacement of H83 and coordination of a water molecule. A similar sequence of events may occur if heme binds to Y75H where coordination of H83 or H75 may occur prior to H32 loop closure and scission of the His coordination and replacement by a water molecule. The fact that the structures of the Y75 and H32 loops are very similar in the Y75H, Y75A, and H32A holo-HasAp structures with only a slight reorientation of R33, D39, and V38 rotating the H32 loop away from the heme is consistent with previous studies indicating heme binding is dominated by π–π stacking and hydrophobic interactions with side chains in the Y75 loop (Figure 6). The crystal structure at 1.32 Å resolution is a good predictor of the hydrogen bonding network, consistent with the Fe–OH2 oscillator predicted by RR where the coordinated water molecule replacing Y75 is strongly hydrogen bonded through H75 and H83.

Figure 6.

Cartoon and stick representations of (A) Y75H holo-HasAp and comparison of the heme-bound wild-type HasAp model with the heme-bound forms of (B) the Y75H HasAp variant, (C) the Y75A HasAp variant, and (D) the H83A HasAp variant. In panel A, the H32 loop and Y75 loop are colored cyan and green, respectively, and heme-coordinating ligands in stick format are colored gold. The ligating water molecule is shown as a sphere, and hydrogen bonds to H75 and H83 are represented by dashed lines. Carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen atoms are colored tan, blue, and red, respectively. The 2Fo − Fc composite omit map, generated using the simulated annealing protocol, is shown as the blue cage and contoured at 2σ. In panels B–D, the wild-type model (PDB entry 3ELL) is colored cyan and the variant model is colored salmon. PDB entries for the Y75A, H83A, and Y75H models are 4O6Q, 4O6S, and 6U87, respectively. Key amino acid residues in the heme binding loops are labeled, and oxygen and nitrogen atoms are colored red and blue, respectively. For the heme-bound Y75H variant, a water molecule occupies the position of the phenolic oxygen in the WT protein.

DISCUSSION

On the basis of previous studies supplementing the P. aeruginosa ΔhasAp strain with WT or holo-HasAp Y75A or H83A variants, we proposed a model for heme-dependent activation of the CSS cascade. In this model, the release of heme from HasAp to HasR involves a concerted release of H32 and Y75 facilitated by weakening of the tyrosinate ligand on transient protonation by H83. This was in part based on the observation of a significant increase in the level of hasR mRNA (a result of activation of the CSS cascade for the Y75A or H83A HasAp variant) compared to that of WT holo-HasAp. This increase in the level of transcription given the fact the total heme available to the strains is identical was attributed to a nonphysiological kinetically trapped “signaling” intermediate that transports heme at a slower rate.29 Interestingly, the crystal structure of the Y75A and H83A holo-HasAp proteins shows the overall fold and positioning of the heme to be almost identical to those of WT holo-HasAp.35 The primary factor of importance is the ligation state of the iron atom. In the H83A holo-HasAp structure, Y75 remains coordinated to the heme, whereas in Y75A holo-HasAp, an exogenous ligand replaces Y75 with H83A, occupying a similar position in the absence of the Y75 ligand. In the H83A holo-HasAp structures, a water molecule or an ethylene glycol from the cryoprotectant forms a hydrogen bond with Y75, essentially replacing the Y75 Oη–H83 Nδ hydrogen bond in WT holo-HasAp.35 RR and EPR analyses of H83A holo-HasAp are consistent with a 6cHS/6cLS mixture as seen here with the Y75H variant. Previous spectroscopic studies of the S. marcescens H83A holo-HasA suggested that disruption of the hydrogen bond resulted in loss of the Tyr ligand,51 but subsequent analysis of H83A holo-HasAp showed that the Tyr ligation is a weaker sixth ligand at room temperature but is retained and enforces the same rhombic low-spin ferric EPR signature at cryogenic temperatures as in WT holo-HasAp.35 While the conformation of the Y75 loop in the Y75A and H83A mutants is similar to that of WT holo-HasAp, the conformation of the H32 loop in both mutants is more affected than in WT holo-HasAp. The reorientation of the H32 loop and several side chains, including R33, D39, and V38, rotate the loop away from the heme, potentially weakening the steric clash upon interaction with HasR. While not true for all crystal forms, it is important to note that R33 forms an important crystal contact in the WT holo-HasAp crystal lattice, and therefore, structural differences in the H32 loop need to be carefully interpreted. The most feasible hypothesis at this time is that modulation of the tyrosinate character of Y75, during interaction with HasR, is required for the concerted release of heme. The loss or disruption of this controlled release leads to the formation of the “kinetically” trapped intermediate. Furthermore, the region of the H32 loop most affected by the previous Y75 loop mutations is the region not visible in the crystal structure of the S. marcescens HasA–HasR complex.52 Moreover, as the H32A mutation also gave a similar signaling profile, the data suggest that preferential loss of either ligand yields the “kinetically” trapped signaling intermediate.

In previous studies, we attributed the inability of the Y75H holo-HasAp to activate the CSS cascade to the potential of a stronger bis-His ligation.29 In an effort to further understand the significance of the His-Tyr motif in controlling the release of heme to HasR, we performed spectroscopic and structural analysis of the Y75H holo-HasAp variant. SPR analysis of the interaction of Y75H holo-HasAp with HasR confirmed the inability to trigger the CSS cascade was not due to disruption of the protein–protein interaction (Figure 1). Moreover, despite the retention of the protein–protein interaction, supplementation of the ΔhasAp strain with [13C]heme-loaded Y75H HasAp showed a growth defect consistent with the lack of [13C]heme-derived biliverdin metabolites compared to WT holo-HasAp supplementation (Figure 2). Taken together, the data are consistent with a stronger heme ligation inhibiting heme sensing and uptake by preventing the release of heme to the receptor.

The absorption, RR, and EPR spectroscopic analyses of Y75H holo-HasAp are consistent with predominantly 6CLS ferric heme species (Figures 3 and 4). Interestingly, rather than a bis-His signature, the detection of a ν(FeIII–OH) stretching frequency at 514 cm−1 in the Y75H holo-HasAp low-frequency RR spectrum is indicative of a hydroxy ligand that is strongly hydrogen bonded. Similarly, ligand-field analysis of the low-spin d5 ferric heme EPR signature reveals ligand-field splitting parameters that fall between a bis-His and His-hydroxy ligation to the heme. The crystal structure of Y75H holo-HasAp is further confirmation of a unique ligation within the heme pocket. As is the case for the Y75A and H83A holo-HasAp structures,35 the heme seating in Y75H holo-HasAp is unchanged from that of WT holo-HasAp (Figure 6). Similarly, the Fe–N and Fe–O ligand bond lengths are similar within 0.2 and 0.1 Å, respectively. The most notable change in the Y75H holo-HasAp structure is in the H32 loop, where similar to the Y75A and H83A holo-HasAp variants (Figure 6C,D), the alternate conformation is rotated away from the heme (Figure 6B). However, as previously mentioned, extreme care must be taken to interpret these conformational changes as R33 is involved in a crystal contact in WT holo-HasAp, but not in the Y75H holo-HasAp crystal lattice. An alternative origin for heme retention in Y75H may be the lack of a covalent linkage between the heme iron and the Y75 loop, providing sufficient flexibility to this His–hydroxy ligation motif to remain after complexation with HasR and to inhibit the transfer of the heme to HasR. Indeed, the hydrogen bonds from H83 and H75 optimize the coordination of a hydroxy group in place of the Tyr75 hydroxy group. More importantly, this new interaction provides sufficient malleability to this His-hydroxy-His binding motif, allowing significant rearrangement of the Y75 loop upon interaction with HasR without displacement and loss of the hydroxy ligating group. The current data suggest that a steric clash between the H32 loop of HasAp with L8 of HasR is not sufficient to drive the conformational rearrangement required to sever the Fe–N ligand but also modulation of the Fe–O bond on the opposite face of the heme to trigger the release of heme upon interaction with HasR.

The critical role of the Tyr-His motif in driving conformational rearrangement and heme release is further supported by the fact the H32 coordination is not conserved among HasA proteins. Yersinia pestis HasA encodes a Gln at position 32 with the heme solely ligated through the conserved Tyr-His motif.53 Interestingly, the Y. pestis apo-HasA (HasAyp) structure is in a closed loop conformation almost identical to the holo-HasA structure, with the only significant difference being rearrangement of the R40 side chain on the distal face of the heme in the holo structure.53 More evidence for the closed loop structure of apo-HasAyp is the extremely fast on rate of heme binding this hemophore displays compared to that of HasAp.53 Interestingly, the R33A HasAp variant disrupts the “zipper-like” interaction of the H32 loop with the protein core required for stabilizing the apo-HasAp open conformation, allowing the H32 loop to adopt a closed conformation similar to that of HasAyp.54 However, the R33A apo-HasAp closed conformation is less efficient in capturing heme than the apo-HasAyp conformation, suggesting there are subtle differences between R33A apo-HasAp and HasAyp in terms of the conformational dynamics and kinetics of heme binding. The authors concluded that the apo-HasAyp closed conformation has evolved to optimize binding to the hydrophobic Y75 platform whereas in R33A apo-HasAp the closed H32 loop obstructs the heme binding pocket. Moreover, the fact that the ability of the H32A holo-HasAp variant to support heme transport is compromised suggests there may be subtle differences between the conformational dynamics and rearrangement between holo-HasAp WT and the H32 loop mutants on interaction with HasR. In this context, it would be interesting to see if the closed conformation of Y. pestis holo-HasAyp upon supplementation of the P. aeruginosa ΔhasAp allelic strain has a signaling and uptake profile similar to that of WT holo-HasAp or the H32A HasAp variant. Taken together with current studies of Y75H holo-HasAp, the accumulated data suggest the Tyr-His motif is critical for coupling modulation of the Fe–O ligand with conformational rearrangements in the H32 and Y75 loops of HasAp required to release heme to HasR. We hypothesize that the Tyr-His motif and its ability to actuate long-range conformational changes within the H(Q)32 loop constitute a conserved mechanism irrespective of a coordinating ligand to the heme. We are further investigating the mechanism of heme release and transport structurally analyzing the HasAp mutants in complex with HasR together with in vivo heme signaling and transport assays. In conclusion, our studies highlight the unique nature of the Tyr-His motif that couples conformational rearrangement on protein–protein interaction to controlled heme release. As such, the unique properties of the conserved Tyr-His motif have been exploited in a variety of bacterial heme transport systems in both Gram-negative and Gram-positive pathogens.55–57

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Prof. Joshua Tesler (Roosevelt University) for helpful discussions regarding the analysis of low-spin d5 systems and for providing access to his ligand-field theory program DLSD5.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 AI134886 to A.W. and R01 GM124203 to W.N.L. A.T.D. was funded by a Ruth L. Kirschstein (NRSA) Individual Predoctoral Fellowship (GM126860).

ABBREVIATIONS

- Has

heme assimilation system

- Phu

Pseudomonas heme uptake system

- BVIX

biliverdin IX

- RR

resonance Raman

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Accession Codes

PSEAE, UniProtKB G3XD33.

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.biochem.1c00389

Contributor Information

Alecia T. Dent, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, School of Pharmacy, University of Maryland, Baltimore, Maryland 21201, United States.

Marley Brimberry, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Franklin College of Arts and Sciences, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 30602, United States;.

Therese Albert, Department of Chemical Physiology and Biochemistry, School of Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon 97239, United States.

William N. Lanzilotta, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Franklin College of Arts and Sciences, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 30602, United States;.

Pierre Moënne-Loccoz, Department of Chemical Physiology and Biochemistry, School of Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon 97239, United States;.

Angela Wilks, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, School of Pharmacy, University of Maryland, Baltimore, Maryland 21201, United States;.

REFERENCES

- (1).Otto BR, Verweij-Van Vught AM, and MacLaren DM (1992) Transferrins and heme-compounds as iron sources for pathogenic bacteria. Crit. Rev. Microbiol 18, 217–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Ganz T (2009) Iron in innate immunity: starve the invaders. Curr. Opin. Immunol 21, 63–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Payne SM, Mey AR, and Wyckoff EE (2016) Vibrio Iron Transport: Evolutionary Adaptation to Life in Multiple Environments. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev 80, 69–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Sheldon JR, and Heinrichs DE (2015) Recent developments in understanding the iron acquisition strategies of gram positive pathogens. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 39, 592–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Contreras H, Chim N, Credali A, and Goulding CW (2014) Heme uptake in bacterial pathogens. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 19, 34–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Huang W, and Wilks A (2017) Extracellular Heme Uptake and the Challenge of Bacterial Cell Membranes. Annu. Rev. Biochem 86, 799–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Costerton JW (2001) Cystic fibrosis pathogenesis and the role of biofilms in persistent infection. Trends Microbiol. 9, 50–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Sadikot RT, Blackwell TS, Christman JW, and Prince AS (2005) Pathogen-host interactions in Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 171, 1209–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Royt PW (1990) Pyoverdine-mediated iron transport. Fate of iron and ligand in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biol. Met 3, 28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Heinrichs DE, Young L, and Poole K (1991) Pyochelin-mediated iron transport in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: involvement of a high-molecular-mass outer membrane protein. Infect. Immun 59, 3680–3684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Hunter RC, Asfour F, Dingemans J, Osuna BL, Samad T, Malfroot A, Cornelis P, and Newman DK (2013) Ferrous iron is a significant component of bioavailable iron in cystic fibrosis airways. mBio 4, No. e00557–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Ochsner UA, Johnson Z, and Vasil ML (2000) Genetics and regulation of two distinct haem-uptake systems, phu and has, in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 146 (Part 1), 185–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Smith AD, and Wilks A (2015) Differential Contributions of the Outer Membrane Receptors PhuR and HasR to Heme Acquisition in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Biol. Chem 290, 7756–7766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Llamas MA, Imperi F, Visca P, and Lamont IL (2014) Cell-surface signaling in Pseudomonas: stress responses, iron transport, and pathogenicity. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 38, 569–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Mascher T (2013) Signaling diversity and evolution of extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors. Curr. Opin. Microbiol 16, 148–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Helmann JD (2002) The extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors. Adv. Microb. Physiol 46, 47–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Sineva E, Savkina M, and Ades SE (2017) Themes and variations in gene regulation by extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors. Curr. Opin. Microbiol 36, 128–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Cunliffe HE, Merriman TR, and Lamont IL (1995) Cloning and characterization of pvdS, a gene required for pyoverdine synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: PvdS is probably an alternative sigma factor. J. Bacteriol 177, 2744–2750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Leoni L, Ciervo A, Orsi N, and Visca P (1996) Iron-regulated transcription of the pvdA gene in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: effect of Fur and PvdS on promoter activity. J. Bacteriol 178, 2299–2313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Leoni L, Orsi N, de Lorenzo V, and Visca P (2000) Functional analysis of PvdS, an iron starvation sigma factor of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol 182, 1481–1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Beare PA, For RJ, Martin LW, and Lamont IL (2003) Siderophore-mediated cell signalling in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: divergent pathways regulate virulence factor production and side-rophore receptor synthesis. Mol. Microbiol 47, 195–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Redly GA, and Poole K (2003) Pyoverdine-mediated regulation of FpvA synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: involvement of a probable extracytoplasmic-function sigma factor, FpvI. J. Bacteriol 185, 1261–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Redly GA, and Poole K (2005) FpvIR control of fpvA ferric pyoverdine receptor gene expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: demonstration of an interaction between FpvI and FpvR and identification of mutations in each compromising this interaction. J. Bacteriol 187, 5648–5657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Vanderpool CK, and Armstrong SK (2003) Heme-responsive transcriptional activation of Bordetella bhu genes. J. Bacteriol 185, 909–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Rossi MS, Paquelin A, Ghigo JM, and Wandersman C (2003) Haemophore-mediated signal transduction across the bacterial cell envelope in Serratia marcescens: the inducer and the transported substrate are different molecules. Mol. Microbiol 48, 1467–1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Biville F, Cwerman H, Letoffe S, Rossi MS, Drouet V, Ghigo JM, and Wandersman C (2004) Haemophore-mediated signalling in Serratia marcescens: a new mode of regulation for an extra cytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factor involved in haem acquisition. Mol. Microbiol 53, 1267–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Lansky IB, Lukat-Rodgers GS, Block D, Rodgers KR, Ratliff M, and Wilks A (2006) The cytoplasmic heme-binding protein (PhuS) from the heme uptake system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an intracellular heme-trafficking protein to the delta-regioselective heme oxygenase. J. Biol. Chem 281, 13652–13662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Ratliff M, Zhu W, Deshmukh R, Wilks A, and Stojiljkovic I (2001) Homologues of neisserial heme oxygenase in gram-negative bacteria: degradation of heme by the product of the pigA gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol 183, 6394–6403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Dent AT, Mourino S, Huang W, and Wilks A (2019) Post-transcriptional regulation of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa heme assimilation system (Has) fine-tunes extracellular heme sensing. J. Biol. Chem 294, 2771–2785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Mourino S, Giardina BJ, Reyes-Caballero H, and Wilks A (2016) Metabolite-driven Regulation of Heme Uptake by the Biliverdin IXbeta/delta-Selective Heme Oxygenase (HemO) of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Biol. Chem 291, 20503–20515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Nguyen AT, O’Neill MJ, Watts AM, Robson CL, Lamont IL, Wilks A, and Oglesby-Sherrouse AG (2014) Adaptation of iron homeostasis pathways by a Pseudomonas aeruginosa pyoverdine mutant in the cystic fibrosis lung. J. Bacteriol 196, 2265–2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Damron FH, Oglesby-Sherrouse AG, Wilks A, and Barbier M (2016) Dual-seq transcriptomics reveals the battle for iron during Pseudomonas aeruginosa acute murine pneumonia. Sci. Rep 6, 39172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Jepkorir G, Rodriguez JC, Rui H, Im W, Lovell S, Battaile KP, Alontaga AY, Yukl ET, Moënne-Loccoz P, and Rivera M (2010) Structural, NMR spectroscopic, and computational investigation of hemin loading in the hemophore HasAp from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Am. Chem. Soc 132, 9857–9872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Yukl ET, Jepkorir G, Alontaga AY, Pautsch L, Rodriguez JC, Rivera M, and Moënne-Loccoz P (2010) Kinetic and spectroscopic studies of hemin acquisition in the hemophore HasAp from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochemistry 49, 6646–6654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Kumar R, Matsumura H, Lovell S, Yao H, Rodriguez JC, Battaile KP, Moënne-Loccoz P, and Rivera M (2014) Replacing the axial ligand tyrosine 75 or its hydrogen bond partner histidine 83 minimally affects hemin acquisition by the Hemophore HasAp from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochemistry 53, 2112–2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Dent AT, and Wilks A (2020) Contributions of the heme coordinating ligands of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa outer membrane receptor HasR to extracellular heme sensing and transport. J. Biol. Chem 295, 10456–10467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Fuhrop JH, and Smith KM, Eds. (1975) Porphyrins and Metalloporphyrins, pp 804–807, Elsevier, Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Centola G, Deredge DJ, Hom K, Ai Y, Dent AT, Xue F, and Wilks A (2020) Gallium(III)-Salophen as a Dual Inhibitor of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Heme Sensing and Iron Acquisition. ACS Infect. Dis 6, 2073–2085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Fu Z-Q, Rose J, and Wang B-C (2005) SGXPro: a parallel workflow engine enabling optimization of program performance and automation of structure determination. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr 61, 951–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, and Zwart PH (2010) PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr 66, 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Emsley P, and Cowtan K (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr 60, 2126–3212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Nicoletti FP, Bustamante JP, Droghetti E, Howes BD, Fittipaldi M, Bonamore A, Baiocco P, Feis A, Boffi A, Estrin DA, and Smulevich G (2014) Interplay of the H-bond donor-acceptor role of the distal residues in hydroxyl ligand stabilization of Thermobifida fusca truncated hemoglobin. Biochemistry 53, 8021–8030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Kraus DW, and Wittenberg JB (1990) Hemoglobins of the Lucina pectinata/bacteria symbiosis. I. Molecular properties, kinetics and equilibria of reactions with ligands. J. Biol. Chem 265, 16043–16053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Howes BD, Feis A, Indiani C, Marzocchi MP, and Smulevich G (2000) Formation of two types of low-spin heme in horseradish peroxidase isoenzyme A2 at low temperature. JBIC, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem 5, 227–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Ehrenberg A, and Poltarasky R (1967), Academic Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- (46).Watari H, Groudinsky O, and Labeyrie F (1967) Electron spin resonance of cytochrome b2 and of cytochrome b2 core. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg 131, 592–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Brautigan DL, Feinberg BA, Hoffman BM, Margoliash E, Preisach J, and Blumberg WE (1977) Multiple low spin forms of the cytochrome c ferrihemochrome. EPR spectra of various eukaryotic and prokaryotic cytochromes c. J. Biol. Chem 252, 574–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).McGarvey BR (1998) Survey of ligand field parameters of strong d5 complexes obtained form the g matrix. Coord. Chem. Rev 170, 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Blumberg WE, and Peisach J (1971) Low-spin compounds of heme proteins. Adv. Chem. Ser 100, 271–291. [Google Scholar]

- (50).Alontaga AY, Rodriguez JC, Schonbrunn E, Becker A, Funke T, Yukl ET, Hayashi T, Stobaugh J, Moënne-Loccoz P, and Rivera M (2009) Structural characterization of the hemophore HasAp from Pseudomonas aeruginosa: NMR spectroscopy reveals protein-protein interactions between Holo-HasAp and hemoglobin. Biochemistry 48, 96–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Caillet-Saguy C, Piccioli M, Turano P, Lukat-Rodgers G, Wolff N, Rodgers KR, Izadi-Pruneyre N, Delepierre M, and Lecroisey A (2012) Role of the iron axial ligands of heme carrier HasA in heme uptake and release. J. Biol. Chem 287, 26932–26943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Krieg S, Huche F, Diederichs K, Izadi-Pruneyre N, Lecroisey A, Wandersman C, Delepelaire P, and Welte W (2009) Heme uptake across the outer membrane as revealed by crystal structures of the receptor-hemophore complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 106, 1045–1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Kumar R, Lovell S, Matsumura H, Battaile KP, Moënne-Loccoz P, and Rivera M (2013) The hemophore HasA from Yersinia pestis (HasAyp) coordinates hemin with a single residue, Tyr75, and with minimal conformational change. Biochemistry 52, 2705–2707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Kumar R, Qi Y, Matsumura H, Lovell S, Yao H, Battaile KP, Im W, Moënne-Loccoz P, and Rivera M (2016) Replacing Arginine 33 for Alanine in the Hemophore HasA from Pseudomonas aeruginosa Causes Closure of the H32 Loop in the Apo-Protein. Biochemistry 55, 2622–2631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Gaudin CF, Grigg JC, Arrieta AL, and Murphy ME (2011) Unique heme-iron coordination by the hemoglobin receptor IsdB of Staphylococcus aureus. Biochemistry 50, 5443–5452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Grigg JC, Mao CX, and Murphy ME (2011) Iron-coordinating tyrosine is a key determinant of NEAT domain heme transfer. J. Mol. Biol 413, 684–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Smith AD, Modi AR, Sun S, Dawson JH, and Wilks A (2015) Spectroscopic Determination of Distinct Heme Ligands in Outer-Membrane Receptors PhuR and HasR of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochemistry 54, 2601–2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]