Abstract

Superior corrosion resistance along with higher mechanical performance is becoming a primary requirement to decrease operational costs in the industries. Nickel-based phosphorus coatings have been reported to show better corrosion resistance properties but suffer from a lack of mechanical strength. Zirconium carbide nanoparticles (ZCNPs) are known for promising hardness and unreactive behavior among variously reported reinforcements. The present study focuses on the synthesis and characterization of novel Ni-P-ZrC nanocomposite coatings developed through the electrodeposition technique. Successful coelectrodeposition of ZCNPs without any observable defects was carried out utilizing a modified Watts bath and optimized conditions. For a clear comparison, structural, surface, mechanical, and electrochemical behaviors of Ni-P and Ni-P-ZrC nanocomposite coatings containing 0.75 g/L ZCNPs were thoroughly investigated. The addition of ZCNPs has a considerable impact on the properties of Ni-P coatings. Enhancement in the mechanical properties (microhardness, nanoindentation, wear, and erosion) is observed due to reinforcement of ZCNPs in the Ni-P matrix, which can be attributed to mainly the dispersion hardening effect. Furthermore, corrosion protection efficiency (PE%) of the Ni-P matrix was enhanced by the incorporation of ZCNPs from 71 to 85.4%. The Ni-P-ZrC nanocomposite coatings provide an exciting option for their utilization in the automotive, electronics, aerospace, oil, and gas industry.

1. Introduction

Corrosion can be regarded as a slow poison for metals and numerous alloys, thus affecting various industries, namely, water treatment plants,1 onshore pipelines,2,3 offshore pipelines,3,4 steelmaking processes,5 refineries,6,7 oil and gas industries,4,7 concrete structures,8,9 arthroplasty,10,11 storage tanks,12 geothermal equipment,4 biomedical devices,13 automobiles,14 microelectronics,7,14 textile industry,15 and aerospace and aeronautical applications.16−18 Adverse effects of corrosion and erosion due to harsh operating conditions have set difficult challenges and thus must be timely addressed, leading to obtaining various smart solutions.19−21 It is worth mentioning that the corrosion cost reaches 3–4% of the developed countries’ GDP.22 Moreover, the estimated cost of the metal deterioration in oil and gas is 170 billion USD per year.22 The corrosion risk can be extended to health and the environment due to failure in oil and gas equipment as a result of the wall thinning of the pipelines. Accordingly, many strategies are developed to mitigate corrosion in a harsh atmosphere, such as organic coatings, corrosion inhibitors, and metallic-based coatings.

Surface engineering of metal–metal alloys using metallic coatings grabbed researchers’ attention because of their promising corrosion solution and improved mechanical strength.20,23−25 Among inorganic coatings, nickel-based coatings are famous for their improved corrosion resistance and superior mechanical properties.26−29 Furthermore, the concept of composites is applied in nickel-based coatings to enhance their wear and erosion capabilities.21,29,30 Nickel-based coatings are synthesized through various methods, namely, direct current electrodeposition, pulse current electrodeposition, and electroless deposition.26,31−33 Direct current electrodeposition of a nickel-based composite coating is utilized by researchers due to its simplicity, stability of chemical bath, ease of tailoring the chemical bath, ease of scaling up and modifying the microstructure, and being economically feasible.34 Various aspects of electrodeposition are extensively studied, such as current density, pH, effects of additives, the effect of change in temperature, and deposition time to tailor the properties of coatings for different applications.26,35−39

The production and characterization of nanoscale species have provided the research community with opportunities to explore attractive improvements in the properties of various matrix materials.40 Reinforcing the Ni-P matrix with hard ceramics to improve its mechanical performance and enhancing its corrosion resistance ability are a comparatively novel idea that becomes tempting when the reinforcements are at the nanoscale. This reinforcing of hard ceramic nanoparticles improves the mechanical strength of the Ni-P coating.41,42 Enhancement in the characteristics of the Ni-P matrix has been obtained by considering numerous reinforcements as reported in the literature such as SiC,42 TiO2,43 C3N4,44 and WC,45 ZrO2,46 TiC,47 etc.

The main objective of the current research is to reinforce the Ni-P matrix with ZCNPs through an electrodeposition technique to develop novel Ni-P-ZrC metallic coatings and explore their impact on its structural, mechanical, wear, erosion, and corrosion characteristics. As per our literature survey, the synthesis of Ni-P-ZrC nanocomposite coatings through an electrodeposition technique and their characterization have not been previously reported. It is observed that the incorporation of ZCNPs into the Ni-P matrix has a significant effect and thus has resulted in remarkable development in properties such as corrosion, mechanical, erosion, and wear. The superior characteristics of Ni-P-ZrC alloys can be attributed to the combination of various factors such as (i) the dispersion hardening effect, (ii) blocking of pores using the inert ZCNPs, and (iii) reduction of active sites existing in the Ni-P matrix.

2. Materials and Methodology

2.1. Materials

The tailored chemical bath was modified from a Watts bath containing nickel chloride hexahydrate, nickel sulfate hexahydrate, sodium chloride, orthophosphoric acid, boric acid, and sodium hypophosphite monohydrate. Zirconium carbide (ZrC) nanopowder of <80 nm average size with a purity of 99.9% was purchased from Sigma Aldrich and used in the chemical bath. Nickel sheets and mild steel sheets were locally purchased to be used as the anode and cathode.

2.2. Sample Preparation

Synthesis of Ni-P-ZrC nanocomposite coatings was accomplished on polished mild steel substrates. In the first step, steel was made to a size of 32 mm coupons by metal sheet operation. Coupons were ground to produce polished samples on abrasive papers (silicon carbide) with gradings of 120, 220, 320, 500, 800, 1000, and 1200. The samples were washed with soap and water. Sonication with acetone was carried out after polishing for 25 min. In order to prevent electrodeposition on both sides of the substrates, tape was used to cover the unpolished sides. The steel specimens were etched in a 15% HCl solution for 40 s and rinsed in warm distilled water before placing it in the coating bath. The schematic representation of the electrodeposition experimental system is represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the employed electrodeposition process.

During the electrodeposition process, a nickel sheet was the anode, the polished steel substrate was the cathode, and they were placed parallel to each other at a distance of ∼30 mm in the chemical bath. The electrodeposition of Ni-P and Ni-P-ZrC (0.75 g/L) nanocomposite coatings was carried out at 65 ± 2 °C. The deposition time was fixed to be 30 min from the initiation of the power supply. In order to thoroughly disperse and prevent the settling down of the ZCNPs, the chemical bath was stirred at 300 ± 5 rpm before an hour of initiating electrodeposition. The tailored chemical bath and optimized deposition conditions are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Tailored Chemical Bath Composition and Optimized Deposition Conditions for Coelectrodeposition of Ni-P and Ni-P-ZrC Nanocomposite Coatings.

| chemical bath and deposition conditions | Ni-P-ZrC |

|---|---|

| nickel sulfate hexahydrate | 250 g L–1 |

| nickel chloride hexahydrate | 15 g L–1 |

| boric acid | 30 g L–1 |

| sodium chloride | 15 g L–1 |

| orthophosphoric acid | 6 g L–1 |

| sodium hypophosphite monohydrate | 20 g L–1 |

| ZrC nanoparticles (<80 nm) | 0 and 0.75 g L–1 |

| pH | 2.0 ± 0.2 |

| temperature | 65 ± 2 °C |

| deposition time | 30 min |

| current density | 48 mA cm–2 |

| bath agitation | 300 rpm |

2.3. Sample Characterization

Structural characterization of the sample was done utilizing an X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku. Miniflex2 Desktop, Tokyo, Japan) employing Cu Kα radiations with a step size of 0.02° in the range of 2θ from 10 to 90°. The morphological study of the developed coatings was explored using a field-emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM; Nova Nano-450, Netherlands). A topographical study was carried out through an atomic force microscopy (AFM-USA) device MFP-3D from Asylum Research (USA). The equipment containing a silicon probe (Al reflex coated Veeco model OLTESPA, Olympus; spring constant, 2 N m–1; resonant frequency, 70 kHz) was used in these tests. All AFM investigations were performed at room temperature using tapping mode in air. Mechanical properties of the samples were tested on a Vickers microhardness tester (FM-ARS9000, USA) and an MFP-3D nanoindenter coupled with an AFM. The measurement of the microhardness was conducted at 25 gf with a dwell time of 10 s. The nanoindentation was evaluated using a Berkovich tip equipped with a diamond indenter bearing a maximum indentation load of 1 mN. More details about testing can be found elsewhere at refs (48) and (49). During wear testing, the sliding velocity was kept constant at a rate of 0.11 m s–1, keeping the constant diameter of the wear scar of 4 mm. The nanocomposite coatings acted as the disc and stainless-steel balls as a sliding medium. This test was carried out at 25 °C under 4 N normal loads and with a total sliding distance of 55 m. Erosion testing was done for the as-synthesized nanocomposite coatings using an air-jet erosion tester. Alumina particles were employed as an erodent as it is commonly used for corrosion testing. The particle size of the as-received alumina (Al2O3) is in the range of 53–84 μm. The experimental setup for performing the erosion tests followed the ASTM G76.50,51 The erodent particles flowed with a 0.94 g min–1 feed rate and were then ejected from the nozzle with a velocity range from 19 to 101 m s–1. The nozzle diameter is 2 mm, and the particle speeds were calculated based on the double-disc approach as Ruff and Ives presented a brief elucidation for calculating the particle speed by directly adjusting the gas pressure. The working distance between the nozzle outlet and the test specimen is 10 mm. The coating sample was mounted on a sample holder facing the nozzle with a 90° incident angle for different exposure times to achieve the maximum effect of surface deformation and depth. The depth and volume loss measurements for the exposed specimens were done using a 3D optical surface metrology system Leica DCM8 profilometer. The corrosion resistance of all the as-synthesized Ni-P and Ni-P-ZrC nanocomposite coatings was investigated using a Gamry 3000 potentiostat/galvanostat/ZRA (Warminster, PA, USA). A saturated silver/silver chloride electrode (Ag/AgCl) was utilized as per reference; however, graphite was used as a counter electrode, and the synthesized coating was employed as a working electrode. At an open-circuit potential, EIS spectra were determined by the AC signal at an amplitude of 10 mV within the 105–10–2 Hz frequency range. Furthermore, the Tafel experiments were conducted at 25 °C using a scan rate of 1 mV s–1. An area exposure of 0.785 cm–2 of the synthesized coating was maintained during all the corrosion measurements.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Structural and Compositional Analysis

Structural analysis of the as-prepared Ni-P and Ni-P-ZrC metallic coatings was investigated using XRD, see Figure 2. The wide peak in the spectra of Ni-P coatings and Ni-P-ZrC nanocomposite coatings indicates the amorphous structure of the as-prepared coatings. The peak at 2θ = 45 represents a face-centered cubic lattice structure of the Ni(111) plane, which has been disturbed by the incorporation of phosphorus atoms resulting in the entire structure being amorphous, which is consistent with the previous finding.37,52,53 Peaks of ZrC cannot be distinguished in the spectra due to the low concentration of ZCNPs, and also, the broad peak of amorphous Ni may have shielded the peaks of ZCNPs.19,54 The broad peak of nickel has sharpened in Ni-P-ZrC nanocomposite coatings, which can be attributed to the presence of ZCNPs, leading to a shift in the structure from amorphous to semiamorphous.52 However, as a comparison, the XRD spectrum of ZCNPs shows a well-defined crystalline behavior.

Figure 2.

XRD diffractograms of ZrC nanoparticles, Ni-P coating, and Ni-P-ZrC nanocomposite coatings containing 0.75 g/L ZCNPs.

3.2. XPS Analysis

Figure 3 represents the XPS survey for the Ni-P-0.75ZrC nanocomposite coating, and the presence of ZCNPs in Ni-P-0.75ZrC nanocomposite coatings was confirmed from XPS analysis. The presence of the main peaks and the corresponding phases for the main elements, which correspond to Ni2p, O1s, C1s, Zr3d, and P2p, can be noticed. It is worth mentioning that oxygen on the coating surface could be due to the incorporation with the other elements.55

Figure 3.

XPS survey spectrum for the Ni-P-0.75ZrC nanocomposite coating.

The individual photoionization fitted data of coating constituent elements and their respective bonding states are shown in Figure 4. High-energy resolution (HER) spectra located at 850.9 and 868.5 eV are ascribed to Ni2p3/2 and Ni2p1/2 in their metallic form, respectively, while, all the peaks positioned at 852.5, 856.8, and 871.9 eV are attributed to nickel oxide or/and nickel hydroxide of Ni2p3/2 and Ni2p1/2 chemically represented as NiO and Ni(OH)2, see Figure 4a, respectively. The construction of Ni(OH)2 and/or NiO could be ascribed to the reaction with hydroxyl ions (OH–) present in the aqueous solution used for electrolysis and other oxidation phenomena.46,48 Moreover, the peaks located at 127.4 and 128.3 eV are linked to 2p2/3 and 2p1/2, see Figure 4b. The peak of 130.5 eV can probably be attributed to (i) phosphorus hypophosphite in its elemental form or/and (ii) the phosphorus species in their intermediate forms (P(I) or/and P(III)), which remain existing inside Ni-P coatings. Nevertheless, the fitted peak at 133.8 eV corresponds to a mixture of hydroxides or/and oxides (P-OH or/and P2O3) with corresponding chemical states.48Figure 4c displays the high-resolution (HER) spectra of Zr 3d. The Zr 3d peaks presented at 180.4 and 183.1 clearly confirm the existence of the ZrC phase within the coating matrix.56,57 Furthermore, the peak situated at 282.5 eV is assigned to the Zr–C bond. Moreover, the peaks at binding energies of 284.3 and 285.2 are attributed to sp2 and sp3 hybridization of carbon, respectively.58,59

Figure 4.

XPS spectra presenting the elemental composition of Ni-P-ZrC nanocomposite coatings, with (a) nickel (Ni2p), (b) phosphorus (P2p), (c) zirconium (Zr3d), and (d) metal carbide.

3.3. Surface Morphology

AFM and FESEM were used to study the morphological and topographical characteristics of the as-prepared alloys. FE-SEM micrographs of Ni-P and Ni-P-ZrC nanocomposite coatings are depicted in Figure 5. As seen in the micrographs, Ni-P coatings (Figure 5a,c) have a plain type of structure, which is modified by the incorporation of ZCNPs. The growth of nodules is observed as a result of introducing ZCNPs in the chemical bath (Figure 5b,d). As for the Ni-P coating, a plain morphology is observed, which has changed to nodular by the addition of ZCNPs in the chemical bath, see Figure 5a,c. This can be assigned to the growth in the number of sites for nucleation of Ni and P ions, which can be deposited on the substrate owing to the large surface area of ZCNPs.54,60,61 Moreover, the surface of as-prepared coatings is crack-free and pore-free, indicating the good quality of the developed Ni-P and Ni-P-ZrC nanocomposite coatings. The thickness of as-prepared Ni-P alloys is around ∼12.0 μm and is achieved under the optimized experimental conditions.

Figure 5.

Highly magnified micrographs (FE-SEM) of developed nanocomposite coatings; Ni-P (a,c) and Ni-P-ZrC nanocomposite coatings (b,d), at two different magnifications.

EDX analysis was further used to evaluate the presence of ZCNPs within the as-prepared alloy matrix, see Figure 6. It can be observed in Figure 6a that in the pure Ni-P coating, nickel (Ni), phosphorus (P), carbon (C), and iron (Fe) peaks are present, confirming the deposition of Ni-P. However, iron and carbon peaks could be due to the steel substrate. The presence of zirconium (Zr), carbon (C), nickel (Ni), and phosphorus (P) confirms the ZCNP inclusion into the Ni-P alloy, see Figure 6b. Additionally, the distribution of each element within Ni-P-ZrC nanocomposite coatings is also provided, indicating the uniform incorporation of ZrC nanospecies in the Ni-P matrix to form the Ni-P-ZrC nanocomposite coating, see Figure 6c.

Figure 6.

EDS elemental mapping of (a) Ni-P and (b) Ni-P-ZrC nanocomposite coatings and (c) detailed elemental mapping.

The composition of Ni-P coating and Ni-P-ZrC nanocomposite coatings is presented in Table 2. The existence of nickel and phosphorus is evident in all the coatings in large percentages. However, a relatively higher presence of carbon can be ascribed to the inference from the substrate and surrounding environmental carbon integrated along with the occurrence of carbon from ZCNPs.62

Table 2. Quantitative Elemental Analysis of Ni-P and Ni-P-ZrC Nanocomposite Coatings.

| sample no. | coating composition | nickel | phosphorus | zirconium | carbon |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ni-P | 88.62% | 11.38% | ||

| 2 | Ni-P-0.75 g/L ZrC | 66.76% | 8.18% | 1.69% | 23.92% |

Many researchers have suggested the codeposition process of several reinforcements within the Ni-P composite system. According to the Guglielmi model,63 particles first gently adsorb at the surface of the cathode through forces attributed to van der Waals attraction and then Coulomb forces responsible for heavy adsorption and bonding. This model does not account for the size of the particle and hydrodynamics of the deposition. The correction factor to resolve for the magnetic stirring was proposed by Berçot et al.64 Bahadormanesh and Dolati improved the original model to account for the significant percentage of the second phase deposition.65 Furthermore, Fransaer et al.66 developed a spherical particle trajectory model in which they listed out different forces acting on any spherical particle, which is revolving in a disc electrode device. Celis et al.67 reported that the electrodeposition process of incorporating reinforcements is said to involve five stages, including (a) reinforcement species being surrounded by an ionic cloud, (b) migration of reinforcement species directed by convective forces near the hydrodynamic layer of the cathode film, (c) adsorption of the reinforcement species accompanied by the cloud of ions at the surface of the cathode, (d) diffusion of reinforcement species by a double layer, and (e) contributing to the permanent incorporation of reinforcement species by the reduction of the ionic cloud within the alloy matrix. To summarize, the electrodeposition process requires the following step: the migration of reinforcement species to the hydrodynamic layer of the cathodic surface from the bulk of the electrolyte. Particles in this layer are attributable to forced convection and electrophoresis. Particles attached to the cathode surface owing to van der Waal forces, and finally, reduction of the ionic cloud around reinforcement species results in irreversible entrapment of the reinforcement species, see Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Schematic illustration of incorporation of ZrC nanoparticles at the cathode (polished steel substrate) to produce Ni-P-ZrC nanocomposite coatings.

A comparison of the surface topography of Ni-P and Ni-P-ZrC nanocomposite coatings is displayed in Figure 8. The incorporation of ZCNPs has enhanced the grain growth and increased the surface roughness of the coatings, which can be observed in the 3D AFM images, see Figure 8a,b. The corresponding profiles of roughness for Ni-P and Ni-P-ZrC nanocomposite coatings are also displayed for a clear comparison, see Figure 8a,b. The Ra (average roughness) of the Ni-P coating is ∼7.7 nm, which increases to 11.6 nm on the addition of 0.75 g/L ZCNPs into the matrix, which can be essentially ascribed to the existence of unsolvable and hard ceramic species into the Ni-P matrix. Moreover, Rq (RMS roughness) also increases from 10.4 to 15.4 nm for the nanocomposite coating compared to the Ni-P coating, which is in agreement with the average roughness. ZCNPs have boosted the surface roughness of the deposited coating.46,48,54

Figure 8.

Three-dimensional AFM micrographs of as-prepared coatings and their profile of surface roughness: (a) Ni-P and (b) Ni-P-ZrC nanocomposite coatings.

3.4. Mechanical Properties

The mechanical properties of the prepared Ni-P coating and Ni-P-ZrC nanocomposite coating were explored by Vickers microhardness testing and nanoindentation techniques. Microhardness outcomes for Ni-P and Ni-P-ZrC nanocomposite coatings are presented in Figure 9a. The addition of ZCNPs has enhanced the coating hardness proving the classical concept of matrices and reinforcements to improve their individual properties. The Ni-P coatings demonstrate a hardness of ∼520 ± 10 HV25, whereas the hardness of Ni-P-ZrC nanocomposite coatings is enhanced to ∼580 ± 15 HV25 contributing an increase of ∼12%. This development in the hardness can be attributed to the resistance to deformation offered by high-strength ZCNPs by inhibiting the dislocation movement and restricting the plastic flow of the Ni-P matrix. It can be considered that a combination of dispersion hardening and construction of the composite structure led to the improvement in microhardness.46,49

Figure 9.

Mechanical characteristics of Ni-P and Ni-P-ZrC nanocomposite coatings; (a) Vickers microhardness and (b) load indentation depth graph of Ni-P and Ni-P-0.75ZrC nanocomposite coatings.

Mechanical properties of the as-fabricated coatings were further analyzed through the nanoindentation technique, and the outcomes are presented in Figure 9b. It can be noted that the loading and unloading curve of Ni-P is a relatively larger area than that of Ni-P-ZrC metallic coatings. The indentation depth of the Ni-P coating decreased from ∼43.6 to ∼33.1 nm by incorporating 0.75 g/L ZCNPs, revealing an enhancement in the indentation resistance.46,48,68 It is noteworthy that the deficiency of discontinuity in the nanoindentation pots indicates that the as-electroplated alloys contain minimum defects (porosity, inhomogeneity, cracks, etc.).

The nanoindentation profiles were utilized for the quantitative investigation of the hardness of the as-electroplated coatings. For a clear comparison, various parameters resulting from load vs indentation depth profiles are also tabulated in Table 3. The mechanical hardness of as-prepared metallic coatings was explored using the Oliver–Pharr technique applying a maximum 1 mN indentation force through the Berkovich diamond indenter. The loading and unloading rate was set at 200 μN/s; meanwhile, a dwell time of 5 s was fixed at a full load. The hardness of the Ni-P alloy improved from 4.98 to 5.75 GPa upon the addition of 0.75 g L–1 ZCNPs. The presence of ZrC nanospecies in the Ni-P alloy obstructs the movement of the dislocations leading to the development of the mechanical properties of the Ni-P-ZrC nanocomposite coatings. Similarly, stiffness of the Ni-P-0.75ZrC nanocomposite coating is observed to increase from 7.49 for the Ni-P alloy to 7.90 kN/m, indicating that an improvement in the deformation resistance was due to the incidence of ZCNPs in the Ni-P matrix within the elastic limit. Moreover, the modulus of elasticity of the Ni-P alloy is boosted from 14.1 to 15.8 GPa by the incorporation of 0.75 g/L ZCNPs.69

Table 3. Derived Parameters from Load Indentation Profiles of Ni-P and Ni-P-ZrC Nanocomposite Coatings.

| sample no. | composition | elasticity (GPa) | stiffness (kN/m) | hardness (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ni-P | 14.05 | 7.49 | 4.98 |

| 2 | Ni-P-ZrC | 15.88 | 7.90 | 5.75 |

3.5. Wear Test

The coefficient of friction (COF) as a function of time for the coelectroplated Ni-P and Ni-P-0.75ZrC nanocomposite coatings is displayed in Figure 10. The friction coefficient decreased from 0.34 for electrodeposited Ni-P to 0.2 after 0.75 g/L ZrC was incorporated in the Ni-P matrix. The COF was boosted at the initial stage of the friction time due to contact friction between the protruding part of the as-electroplated substrates and the stainless-steel ball. The COF of the metallic Ni-P coating oscillated after 400 s and significantly increased to a higher value after 800 s, which could be ascribed to the coating removed from the substrate resulting from destruction (shear) of attachment between the metallic alloy and counterface asperities. It is noteworthy that the presence of COF fluctuation can be categorized among vast and brief domains. These instabilities could be ascribed to the ejection and accretion of the wear debris.49,68−70 On the contrary, in the case of Ni-P-ZrC, a smooth and constant COF was observed after 200 s of friction time, which could be attributed to the lubrication influence of the nanospecies.

Figure 10.

Wear test of the as-electrodeposited nanocomposite coatings prior to and after the incorporation of ZrC nanospecies.

The wear rate (ws) of the metallic Ni-P coatings prior to and after incorporation of ZrC is calculated by the following equation.71

| 1 |

where w is the loss of weight (g), l represents total sliding displacement (m), and L is attributed to the load applied (N) during the test. The wear rate (ws) of Ni-P is lessened from ∼89 to 38 μg N–1 m–1 due to the incorporation of ZrC nanospecies. Moreover, the wear track and depth of Ni-P alleviated from 456 and 8.1 μm to 295 and 4.4 μm as a result of the incorporation of 0.75 g/L ZrC nanoparticles (Figure 11c,d).

Figure 11.

SEM images of (a) Ni-P and (b) Ni-P-0.75 g/L ZrC after wear tests with their wear depth profile (c,d).

Figure 12a illustrates the SEM image of the worn surface of the Ni-P metallic coatings at higher magnification. The formation of fatigue microcracks in the Ni-P metallic coating as a result of inherent properties, such as low hardness, ductility, an apparent poor adhesion, and internal stress in the coating matrix, can be observed. The attendance of cavities or grooves could be attributed to the removal of tribolayers or surface oxide layers, aiding slipping wear by resting with the worn metallic coatings and abrasive as a separate identity.71 Accordingly, the wear regime in Ni-P coatings is adhesive. Figure 12b shows characteristic plowing furrows without any visible microcracks, which are attributed to the enhanced hardness value of nanocomposite coatings. The incorporation of ZCNPs into Ni-P exhibits linear wear tracks, indicating an abrasive wear approach.72

Figure 12.

Highly magnified SEM images of wear track areas of (a) Ni-P and (b) Ni-P/0.75ZrC metallic alloy.

3.6. Erosion Test

Figure 13a represents the maximum measured depth versus particle speed dependence at the same exposure time. It can be estimated that the depth is proportional to the particles’ velocity, indicating higher coating loss at a higher speed. Moreover, the maximum erosion depth is lessened from 16.3 to 13.5 μm with amending 0.75 g/L ZrC to the coating matrix at 101 m s–1. In the meantime, Figure 13b depicts the volume loss of Ni-P and Ni-P-0.75ZrC nanocomposite coatings at different speeds of the erodent particles. The volume loss rate is derived from the average erosion depth and the measured eroded area per exposure time. As expected, the Ni-P-0.75ZrC nanocomposite coatings have better erosion resistance than the Ni-P coating. Moreover, the volume loss rate at 19 m s–1 diminished from 1.23 to 0.38 μm3 s–1 for Ni-P and Ni-P-0.75ZrC alloys, respectively, indicating that damage in the Ni-P-0.75ZrC coating is three times lower than that of the bare coating at low erodent speed. Meanwhile, the volume loss rate at 101 m s–1 of the erodent particles is reduced from 3.7 to 2.9 μm3 s–1 for Ni-P and Ni-P-0.75ZrC coatings.

Figure 13.

(a) Maximum erodent depth and (b) volume loss for the Ni-P and Ni-P-0.75ZrC nanocomposite coatings at different particle velocities after 30 s of erosion time.

Figure 14 depicts the optical profilometry of the eroded substrates of the Ni-P and Ni-P-0.75ZrC nanocomposite coatings after 30 s of erosion time at 101 m s–1. It can be seen that the surface roughness for the Ni-P coating is lower when compared to as-synthesized Ni-P-0.75ZrC nanocomposite coatings after erosion tests, as seen in Figure 14a,b. Additionally, the penetration depth of the Ni-P alloy is higher than that of the Ni-P-0.75ZrC nanocomposite coating, as demonstrated in Figure 14c,d.

Figure 14.

Topographic images of (a) Ni-P and (b) Ni-P-0.75ZrC and their respective depth and width profile (c,d) after 30 s of erosion time at a 101 m/s particle velocity.

3.7. Corrosion Studies

3.7.1. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS)

EIS is a widely accepted method for exploring the corrosion mitigation of the as-fabricated coatings. EIS graphs of the polished carbon steel, Ni-P, and Ni-P-0.75ZrC nanocomposite coatings are shown in Figure 15. Experimental data for the substrate were fitted using the modified version of the Randle cell in which a pure capacitor was improvised with a constant phase element to account for the pure capacitance, as shown in Figure 16a. For describing the degradation behavior of Ni-P and Ni-P-ZrC nanocomposite coatings, a two-time constant cascaded electrical equivalent circuit was employed to fit the EIS data set, as shown in Figure 16b. The electric circuits consist of Rs for the resistance of the brine solution used for the test, whereas Rpo and Rct account for the resistance due to pores and resistance due to transfer of charge of coatings. Constant phase elements (CPE1 and CPE2) were utilized instead of a pure capacitor to justify the discrepancy at the surface and interface of the metallic coating computed from the following equation46

| 2 |

in which Q stands for admittance, ω is the angular frequency, and n is the exponent for the constant phase element, which is responsible for the nature of capacitance such that closer to unity means a pure capacitor.

Figure 15.

(a) Bode plot of the polished carbon steel, Ni-P, and Ni-P-0.75 g/L-ZrC nanocomposite coatings containing the frequency impedance magnitude curve and (b) frequency phase angle curve after 2 h of immersion in 3.5 wt % NaCl solution.

Figure 16.

Equivalent electric circuits applied to fit EIS data for (a) substrate and (b) Ni-P and Ni-P-0.75ZrC nanocomposite coatings.

The Bode plots of the polished steel substrate, Ni-P coating, and nanocomposite coating are presented in Figure 15. It can be perceived that the corrosion resistance of the polished steel substrate is relatively small (260 Ω cm2). Ni-P coatings possess more corrosion resistance than carbon steel as the impedance value of the Ni-P coating is 1782.8 Ω cm2, which can be ascribed to the construction of a protective film of hypophosphite as a result of the electrochemical reaction of saline solution with the Ni-P coating.54,73 Further incorporation of secondary phase ZCNPs in the Ni-P matrix changed the impedance response, resulting in widening of the phase angle plot. This implies an additional protective nanocomposite coating (move toward higher frequencies) and, conversely, the existence of other activities (reduced corrosion).48,49,71 The improvement in the impedance of nanocomposite coatings can be attributed to reducing the dynamic corrosion sites due to the trapping of hard, inactive, and corrosion-resistant ZrC nanoparticles. Interestingly, the incorporation of 0.75 g/L ZrC nanoparticles increased the Rct value to 8353 Ω cm2, which is four times higher than that of the Ni-P alloy.

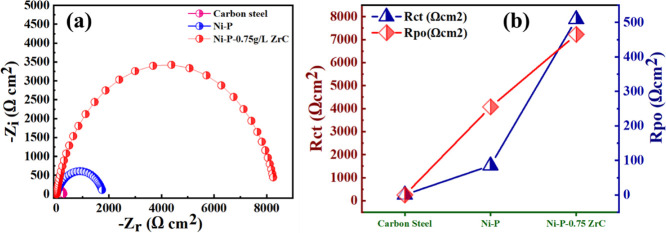

Figure 17a shows the Nyquist plots for the polished carbon steel substrate, Ni-P, and Ni-P-0.75ZrC nanocomposite coatings. The two-time constant equivalent circuit was used to fit experimental data as exhibited in Figure 16b. The semicircular radius of the Nyquist curve reveals a successive increase, pointing to high corrosion impedance resulting from incorporating ZrC nanoparticles. The incorporation of ZrC nanospecies in the Ni-P alloy increased the polarization and pore resistance of the as-fabricated coatings, see Figure 17b. Enhancement in the corrosion resistance of the Ni-P alloy as a result of reinforcing the inert ZrC nanospecies that fill the defects existing in the Ni-P matrix such as pores and microcracks leads to a burden in the entrance of the hydrated Cl– species to reach the carbon steel surface.46,48,71

Figure 17.

(a) Nyquist plot for carbon steel and the as-fabricated Ni-P and Ni-P-0.75ZrC nanocomposite coatings in 3.5 wt % NaCl solution and (b) variation of Rpo and Rct on the substrate, Ni-P, and Ni-P-0.75ZrC nanocomposite coatings.

3.7.2. Tafel Test

Tafel polarization was further utilized to evaluate the corrosion resistance of the polished steel substrate, pure Ni-P coating, and as-prepared Ni-P-ZrC nanocomposite coatings with 0.75 g/L ZrC nanoparticles by setting the rate of scan at 1 mV s–1 described in Figure 18. Electrochemical corrosion currents (icorr) were acquired from the fitted curve and are presented in Table 4. In addition, the efficiency of corrosion protection (PE%) was estimated utilizing the following formulation71

| 3 |

where i1 is the current density of the polished steel substrate and i2 is the current density of coated samples. Polished carbon steel is observed to have the highest current density of 56.9 μA cm–2 with an electrode potential of 658 mV. However, the maximum value of current density for the Ni-P coating is observed to be 16.5 μA cm–2 at a potential of 486 mV, showing development in the corrosion resistance of 71.03%. On the other hand, the incorporation of 0.75 g/L ZCNPs considerably alleviated the icorr to 8.3 μA cm–2 with almost 85.4% development in the corrosion resistance.

Figure 18.

Tafel plots of polished carbon steel, Ni-P coating, and Ni-P-0.75ZrC nanocomposite coating in 3.5 wt % NaCl solution.

Table 4. Comparison of the Corrosion Protection Efficiency (PE%) Obtained from icorr for the Current Study and Numerous Reported Results from the Literature.

| sample no. | sample | deposition technique | icorr (μA cm–2) | PE% | ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | polished steel | electrodeposition | 56.86 | current study | |

| Ni-P | 16.47 | 71% | |||

| Ni-P-0.75 g/L ZrC | 8.3 | 85% | |||

| 2 | uncoated steel | electrodeposition | 39.3 | (48) | |

| Ni-P | 28.6 | 28.4% | |||

| Ni-P-Y2O3-0.25 g/L | 19.6 | 49.1% | |||

| Ni-P-Y2O3-0.5 g/L | 15.4 | 61.5% | |||

| Ni-P-Y2O3-0.75 g/L | 8.9 | 77.7% | |||

| Ni-P-Y2O3-1.0 g/L | 3.7 | 90.8% | |||

| 3 | carbon steel | electrodeposition | 55.94 | (47) | |

| Ni–P | 38.43 | 31.3% | |||

| Ni–P 0.5 g L–1 TiC | 25.62 | 54.2% | |||

| Ni–P 1.0 g L–1 TiC | 7.79 | 86.0% | |||

| Ni–P 1.5 g L–1 TiC | 6.49 | 88.4% | |||

| Ni–P 2.0 g L–1 TiC | 4.91 | 91.2% | |||

| 4 | mild steel | electrodeposition | 79 | (49) | |

| Ni–B | 50 | 36% | |||

| Ni–P | 31 | 60% | |||

| Ni–B/Ni–P | 17 | 78% | |||

| Ni–B/Ni–P–CeO2 | 7.5 | 90% | |||

| 5 | HSLA steel | pulse electrodeposition | 50 | (76) | |

| Ni–P | 30 | 40% | |||

| Ni–P/0.25TiC | 16 | 68% | |||

| Ni–P/0.50TiC | 7 | 86% | |||

| Ni–P/0.75TiC | 3 | 94% | |||

| 6 | substrate | electroless deposition | 40.3 | (73) | |

| Ni-P coating | 7.1 | 74.8% | |||

| duplex Ni-P-ZrO2 coating | 3.717 | 87.8% | |||

| 7 | substrate | electroless deposition | 8.0 | (77) | |

| Ni–P coating | 4.0 | 50% | |||

| Ni–P–WC coating | 1.0 | 87.5% | |||

| 8 | uncoated | electroless deposition | 20.3 | (78) | |

| Ni-P | 4.17 | 79.5% | |||

| Ni-P CNT 0.25 | 3.28 | 83.8% | |||

| Ni-P CNT 0.5 | 2.38 | 88.3% | |||

| Ni-P CNT 1.0 | 2.01 | 90.1% | |||

| 9 | Ni–P (as-deposited) | electrodeposition | 177 | 86.7% | (79) |

| Ni–P–C (as-deposited) | 170 | 87.3% | |||

| Ni–P (heat-treated) | 139 | 89.6% | |||

| Ni–P–C (heat-treated) | 88 | 93.3% | |||

| 10 | substrate | electroless deposition | 2.65 | (80) | |

| Ni–P (used bath A) | 0.47 | 82% | |||

| Ni–P (used bath B) | 0.58 | 78% | |||

| Ni–P (used bath C) | 0.65 | 75% |

Figure 19 shows the SEM images of (a) Ni-P and (b) Ni-P-0.75ZrC after corrosion tests in 3.5 wt % NaCl solution. It can be observed that the Ni-P coating is significantly corroded; however, Ni-P-0.75ZrC exhibited a slight influence on the deposited coating with the formation of few pits. The improvement can be associated with incorporating ZCNPs in the Ni-P coating matrix, which has enhanced corrosion mitigation after the addition of the ZCNPs by reducing the active positions for the adsorption of Cl– ions on the flaws of coatings such as pores and cracks.74,75

Figure 19.

SEM images of (a) Ni-P and (b) Ni-P-0.75ZrC after corrosion tests in saline water.

Table 4 compares the protection efficiency of the as-electrodeposited Ni-P-0.75ZrC with the reported nanocomposite coatings in the literature.

4. Conclusions

Ni-P and Ni-P-ZrC nanocomposite coatings containing 0.75 g/L ZrC nanoparticles (ZCNPs) were successfully developed through the electrodeposition technique. A comparison of structural, surface, mechanical (hardness, nanoindentation, wear, and erosion), and electrochemical properties (corrosion resistance) indicates that Ni-P-0.75ZrC nanocomposite coatings demonstrate improved properties when compared with Ni-P coatings. The improvement in mechanical properties can be ascribed to the dispersion hardening effect and formation of a composite structure. The enhancement in the corrosion resistance properties can be regarded as the effect of reduction in the active area of the Ni-P matrix by the presence of inactive ZCNPs. The tempting properties of Ni-P-0.75ZrC nanocomposite coatings provide their potential application in various industries.

Acknowledgments

The present work is supported by the Qatar University Grant IRCC-2020-006. The opinions expressed in this article are solely the responsibility of the authors. The authors acknowledge the services of the Central Laboratory Unit (CLU), Qatar University for microstructural analysis (FE-SEM/EDS). The XPS facility of the Gas Processing Center (GPC), Qatar University, was utilized to study compositional analysis. Open access funding provided by the Qatar National Library.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Xu X.; Liu S.; Liu Y.; Smith K.; Cui Y. Corrosion of stainless steel valves in a reverse osmosis system: Analysis of corrosion products and metal loss. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2019, 105, 40. 10.1016/j.engfailanal.2019.06.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Melchers R. E. Corrosion of carbon steel in presence of mixed deposits under stagnant seawater conditions. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2017, 45, 29–42. 10.1016/j.jlp.2016.11.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Renpu W.Chapter 11 - Oil and Gas Well Corrosion and Corrosion Prevention. In Advanced Well Completion Engineering; (3rd Edition), Renpu W., Ed. Gulf Professional Publishing: 2011, pp. 617–700. [Google Scholar]

- Nogara J.; Zarrouk S. J. Corrosion in geothermal environment Part 2: Metals and alloys. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev 2018, 82, 1347–1363. 10.1016/j.rser.2017.06.091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teng L.Chapter 3.2 - Refractory Corrosion During Steelmaking Operations. In Treatise on Process Metallurgy; Seetharaman S., Ed. Elsevier: Boston, 2014; pp. 283–303. [Google Scholar]

- Speight J. G.Corrosion. In Subsea and Deepwater Oil and Gas Science and Technology; Speight J. G., Ed. Gulf Professional Publishing: Boston, 2015; pp. 213–256. [Google Scholar]

- Shakoor R.; Kahraman R.; Gao W.; Wang Y. Synthesis, characterization and applications of electroless Ni-B coatings-A review. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2016, 11, 2486–2512. [Google Scholar]

- Singh R.Corrosion Principles and Types of Corrosion. In Corrosion Control for Offshore Structures; Singh R., Ed. Gulf Professional Publishing: Boston, 2014, pp. 7–40. [Google Scholar]

- Popov B. N.Corrosion of Structural Concrete. In Corrosion Engineering; Popov B. N., Ed. Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2015, pp. 525–556, 10.1016/B978-0-444-62722-3.00012-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pivec R.; Meneghini R. M.; Hozack W. J.; Westrich G. H.; Mont M. A. Modular Taper Junction Corrosion and Failure: How to Approach a Recalled Total Hip Arthroplasty Implant. J. Arthroplasty 2014, 29, 1–6. 10.1016/j.arth.2013.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H. J. The Local Effects of Metal Corrosion in Total Hip Arthroplasty. Orthop. Clin. 2014, 45, 9–18. 10.1016/j.ocl.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panossian Z.; Almeida N. L. d.; Sousa R. M. F. d.; Pimenta G. d. S.; Marques L. B. S. Corrosion of carbon steel pipes and tanks by concentrated sulfuric acid: A review. Corros. Sci. 2012, 58, 1–11. 10.1016/j.corsci.2012.01.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwood D. J.Corrosion in Body Fluids. In Reference Module in Materials Science and Materials Engineering; Elsevier: 2016, 10.1016/B978-0-12-803581-8.01614-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng T.-H.; Wu A. T. Corrosion on automobile printed circuit broad. Microelectron. Reliab. 2019, 98, 19–23. 10.1016/j.microrel.2019.04.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radojković B.; Ristić S.; Polić S.; Jančić-Heinemann R.; Radovanović D. Preliminary investigation on the use of the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser to clean corrosion products on museum embroidered textiles with metallic yarns. J. Cult. Heritage 2017, 23, 128–137. 10.1016/j.culher.2016.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song D.; Li C.; Liang N.; Yang F.; Jiang J.; Sun J.; Wu G.; Ma A.; Ma X. Simultaneously improving corrosion resistance and mechanical properties of a magnesium alloy via equal-channel angular pressing and post water annealing. Mater. Des. 2019, 166, 107621. 10.1016/j.matdes.2019.107621. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zuleta A. A.; Galvis O. A.; Castaño J. G.; Echeverría F.; Bolivar F. J.; Hierro M. P.; Pérez-Trujillo F. J. Preparation and characterization of electroless Ni–P–Fe3O4 composite coatings and evaluation of its high temperature oxidation behaviour. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2009, 203, 3569–3578. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2009.05.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Czerwinski F. Controlling the ignition and flammability of magnesium for aerospace applications. Corros. Sci. 2014, 86, 1–16. 10.1016/j.corsci.2014.04.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Safavi M. S.; Rasooli A. Ni-P-TiO2 nanocomposite coatings with uniformly dispersed Ni3Ti intermetallics: Effects of current density and post heat treatment. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 372, 252–259. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2019.05.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Montemor M. F. Functional and smart coatings for corrosion protection: A review of recent advances. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2014, 258, 17–37. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2014.06.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil M. W.; Salah Eldin T. A.; Hassan H. B.; El-Sayed K.; Abdel Hamid Z. Electrodeposition of Ni–GNS–TiO2 nanocomposite coatings as anticorrosion film for mild steel in neutral environment. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2015, 275, 98–111. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2015.05.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi D.; Lepková K.; Becker T. Carbon steel corrosion: a review of key surface properties and characterization methods. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 4580–4610. 10.1039/C6RA25094G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. H.; Chen J. L.; Liu Z.; Yu M.; Li S. M. Fabrication of Zn–Ni/Ni–P compositionally modulated multilayer coatings. Mater. Corros. 2013, 64, 340. 10.1002/maco.201106140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grumezescu V.; Negut I.. Chapter 14 - Nanocoatings and thin films. In Materials for Biomedical Engineering; Grumezescu V.; Grumezescu A. M., Eds. Elsevier: 2019, pp. 463–477. [Google Scholar]

- Surmenev R. A. A review of plasma-assisted methods for calcium phosphate-based coatings fabrication. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2012, 206, 2035–2056. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2011.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wasekar N. P.; Haridoss P.; Seshadri S. K.; Sundararajan G. Influence of mode of electrodeposition, current density and saccharin on the microstructure and hardness of electrodeposited nanocrystalline nickel coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2016, 291, 130–140. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2016.02.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang-tao X.; Yu-jie D.; Wei Z.; Tian-dong X. Microstructure and texture evolution of electrodeposited coatings of nickel in the industrial electrolyte. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2017, 330, 170–177. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2017.09.078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salehikahrizsangi P.; Raeissi K.; Karimzadeh F.; Calabrese L.; Patane S.; Proverbio E. Erosion-corrosion behavior of highly hydrophobic hierarchical nickel coatings. Colloids Surf., A 2018, 558, 446–454. 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2018.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi A.Microstructure evolution and strengthening mechanism in Ni-based composite coatings; 2016.

- He Y.; Wang S. C.; Walsh F. C.; Chiu Y. L.; Reed P. A. S. Self-lubricating Ni-P-MoS2 composite coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2016, 307, 926–934. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2016.09.078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Shu X.; Wei S.; Liu C.; Gao W.; Shakoor R. A.; Kahraman R. Duplex Ni–P–ZrO2/Ni–P electroless coating on stainless steel. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 630, 189–194. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2015.01.064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shang W.; Zhan X.; Wen Y.; Li Y.; Zhang Z.; Wu F.; Wang C. Deposition mechanism of electroless nickel plating of composite coatings on magnesium alloy. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2019, 207, 1299–1308. 10.1016/j.ces.2019.07.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Do Q.; An H.; Wang G.; Meng G.; Wang Y.; Liu B.; Wang J.; Wang F. Effect of cupric sulfate on the microstructure and corrosion behavior of nickel-copper nanostructure coatings synthesized by pulsed electrodeposition technique. Corros. Sci. 2019, 147, 246–259. 10.1016/j.corsci.2018.11.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen L.; Fan M.; Qiu M.; Jiang W.; Wang Z. Superhydrophobic nickel coating fabricated by scanning electrodeposition. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 483, 706–712. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.04.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sknar Y. E.; Savchuk O. O.; Sknar I. V. Characteristics of electrodeposition of Ni and Ni-P alloys from methanesulfonate electrolytes. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 423, 340–348. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.06.146. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J.-X.; Zhao W.-Z.; Zhang G. F. Influence of electrodeposition parameters on the deposition rate and microhardness of nanocrystalline Ni coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2009, 203, 1815–1818. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2009.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knyazev A. V.; Fishgoit L. A.; Chernavskii P. A.; Safonov V. A.; Filippova S. E. Magnetic properties of electrodeposited amorphous nickel–phosphorus alloys. Russ. J. Electrochem. 2017, 53, 270–274. 10.1134/S1023193517030090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davalos C. E.; Lopez J. R.; Ruiz H.; Méndez A.; Antano-Lopez R.; Trejo G. Study of the Role of Boric Acid During the Electrochemical Deposition of Ni in a Sulfamate Bath. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2013, 8, 9785–9800. [Google Scholar]

- Akbari R.; Godeau G.; Mohammadizadeh M.; Guittard F.; Darmanin T. The influence of bath temperature on the one-step electrodeposition of non- wetting copper oxide coatings. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 503, 144094. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.144094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li B.; Zhang W. A novel Ni-B/YSZ nanocomposite coating prepared by a simple one-step electrodeposition at different duty cycles. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 1519. 10.1016/j.jmrt.2019.11.077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lelevic A.; Walsh F. C. Electrodeposition of NiP alloy coatings: A review. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 369, 198–220. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2019.03.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hansal W. E. G.; Sandulache G.; Mann R.; Leisner P. Pulse-electrodeposited NiP–SiC composite coatings. Electrochim. Acta 2013, 114, 851–858. 10.1016/j.electacta.2013.08.182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saravanan I.; Elayaperumal A.; Devaraju A.; Karthikeyan M.; Raji A. Wear behaviour of electroless Ni-P and Ni-P-TiO2 composite coatings on En8 steel. Mater. Today: Proc. 2020, 22, 1135. 10.1016/j.matpr.2019.12.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fayyad E. M.; Abdullah A. M.; Mohamed A. M. A.; Jarjoura G.; Farhat Z.; Hassan M. K. Effect of electroless bath composition on the mechanical, chemical, and electrochemical properties of new NiP–C3N4 nanocomposite coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 362, 239–251. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2019.01.087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zoikis-Karathanasis A.; Pavlatou E. A.; Spyrellis N. The effect of heat treatment on the structure and hardness of pulse electrodeposited NiP–WC composite coatings. Electrochim. Acta 2009, 54, 2563–2570. 10.1016/j.electacta.2008.07.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sliem M. H.; Shahzad K.; Sivaprasad V. N.; Shakoor R. A.; Abdullah A. M.; Fayyaz O.; Kahraman R.; Umer M. A. Enhanced mechanical and corrosion protection properties of pulse electrodeposited NiP-ZrO2 nanocomposite coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 403, 126340. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2020.126340. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fayyaz O.; Khan A.; Shakoor R. A.; Hasan A.; Yusuf M. M.; Montemor M. F.; Rasul S.; Khan K.; Faruque M. R. I.; Okonkwo P. C. Enhancement of mechanical and corrosion resistance properties of electrodeposited Ni–P–TiC composite coatings. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5327. 10.1038/s41598-021-84716-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahgat Radwan A.; Ali K.; Shakoor R. A.; Mohammed H.; Alsalama T.; Kahraman R.; Yusuf M. M.; Abdullah A. M.; Fatima Montemor M.; Helal M. Properties enhancement of Ni-P electrodeposited coatings by the incorporation of nanoscale Y2O3 particles. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 457, 956–967. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.06.241. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf M. M.; Radwan A. B.; Shakoor R. A.; Awais M.; Abdullah A. M.; Montemor M. F.; Kahraman R. Synthesis and characterisation of Ni–B/Ni–P–CeO2 duplex composite coating. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2018, 48, 391. 10.1007/s10800-018-1168-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ASTM G76-04 Standard Test Method for Conducting Erosion Tests by Solid Particle Impingement Using Gas Jets. 2004.

- C Okonkwo P.; H Sliem M.; Hassan Sk M.; Abdul Shakoor R.; Amer Mohamed A. M.; M Abdullah A. M.; Kahraman R. Erosion Behavior of API X120 Steel: Effect of Particle Speed and Impact Angle. Coatings 2018, 8, 343. 10.3390/coatings8100343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y.; Chen W.; Zhou C.; Xu H.; Gao W. Fabrication and characterization of electroless Ni–P–ZrO2 nano-composite coatings. Appl. Nanosci. 2011, 1, 19–26. 10.1007/s13204-011-0003-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nava D.; Dávalos C.; Martínez-Hernández A.; Federico M.; Meas Y.; Ortega R.; Perez Bueno J.; Trejo G.; Sanfandila P.; Escobedo P.; Querétaro M. Effects of Heat Treatment on the Tribological and Corrosion Properties of Electrodeposited Ni-P Alloys. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2013, 8, 2670–2681. [Google Scholar]

- Luo H.; Wang X.; Gao S.; Dong C.; Li X. Synthesis of a duplex Ni-P-YSZ/Ni-P nanocomposite coating and investigation of its performance. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2017, 311, 70–79. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2016.12.075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balaceanu M.; Braic M.; Braic V.; Vladescu A.; Negrila C. Surface Chemistry of Plasma Deposited ZrC Hard Coatings. J. Optoelectron. Adv. Mater. 2005, 7, 2557. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelkader A. M.; Fray D. J. Synthesis of self-passivated, and carbide-stabilized zirconium nanopowder. J. Nanopart. Res. 2013, 15, 2112. 10.1007/s11051-013-2112-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Won Y. S.; Kim Y. S.; Varanasi V. G.; Kryliouk O.; Anderson T. J.; Sirimanne C. T.; McElwee-White L. Growth of ZrC thin films by aerosol-assisted MOCVD. J. Cryst. Growth 2007, 304, 324–332. 10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2006.12.071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S. S.; Sharma A.; Rao G. M.; Suwas S. Investigations on the effect of substrate temperature on the properties of reactively sputtered zirconium carbide thin films. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 695, 1020–1028. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2016.10.225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Long Y.; Javed A.; Chen J.; Chen Z. k.; Xiong X. Phase composition, microstructure and mechanical properties of ZrC coatings produced by chemical vapor deposition. Ceram. Int. 2014, 40, 707–713. [Google Scholar]

- Ping Z.; He Y.; Gu C.; Zhang T. Y. Mechanically assisted electroplating of Ni–P coatings on carbon steel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2008, 202, 6023–6028. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2008.06.183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elias L.; Bhat K. U.; Hegde A. C. Development of nanolaminated multilayer Ni–P alloy coatings for better corrosion protection. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 34005–34013. 10.1039/C6RA01547F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pouladi S.; Shariat M. H.; Bahrololoom M. E. Electrodeposition and characterization of Ni–Zn–P and Ni–Zn–P/nano-SiC coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2012, 213, 33–40. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2012.10.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmi N. Kinetics of the Deposition of Inert Particles from Electrolytic Baths. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1972, 119, 1009. 10.1149/1.2404383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berçot P.; Peña-Muñoz E.; Pagetti J. Electrolytic composite Ni–PTFE coatings: an adaptation of Guglielmi’s model for the phenomena of incorporation. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2002, 157, 282–289. 10.1016/S0257-8972(02)00180-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bahadormanesh B.; Dolati A. The kinetics of Ni–Co/SiC composite coatings electrodeposition. J. Alloys Compd. 2010, 504, 514–518. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2010.05.154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fransaer J.; Celis J. P.; Roos J. R. Analysis of the Electrolytic Codeposition of Non-Brownian Particles with Metals. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1992, 139, 413–425. 10.1149/1.2069233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Celis J. P.; Roos J. R.; Buelens C. A Mathematical Model for the Electrolytic Codeposition of Particles with a Metallic Matrix. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1987, 134, 1402–1408. 10.1149/1.2100680. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fayyad E. M.; Hassan M. K.; Rasool K.; Mahmoud K. A.; Mohamed A. M. A.; Jarjoura G.; Farhat Z.; Abdullah A. M. Novel electroless deposited corrosion — resistant and anti-bacterial NiP–TiNi nanocomposite coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 369, 323–333. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2019.04.064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shakoor R. A.; Kahraman R.; Waware U.; Wang Y.; Gao W. Properties of electrodeposited Ni–B–Al2O3 composite coatings. Mater. Des. 2014, 64, 127–135. 10.1016/j.matdes.2014.07.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allahyarzadeh M. H.; Aliofkhazraei M.; Rouhaghdam A. S.; Alimadadi H.; Torabinejad V. Mechanical properties and load bearing capability of nanocrystalline nickel-tungsten multilayered coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 386, 125472. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2020.125472. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radwan A. B.; Shakoor R. A. Aluminum nitride (AlN) reinforced electrodeposited Ni–B nanocomposite coatings. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 9863–9871. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2019.12.261. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alirezaei S.; Monirvaghefi S. M.; Salehi M.; Saatchi A. Wear behavior of Ni–P and Ni–P–Al2O3 electroless coatings. Wear 2007, 262, 978–985. 10.1016/j.wear.2006.10.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo H.; Leitch M.; Zeng H.; Luo J. L. Characterization of microstructure and properties of electroless duplex Ni-W-P/Ni-P nano-ZrO2 composite coating. Mater. Today Phys. 2018, 4, 36–42. 10.1016/j.mtphys.2018.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farzaneh A.; Mohammadi M.; Ehteshamzadeh M.; Mohammadi F. Electrochemical and structural properties of electroless Ni-P-SiC nanocomposite coatings. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2013, 276, 697–704. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2013.03.156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sadreddini S.; Salehi Z.; Rassaie H. Characterization of Ni–P–SiO2 nano-composite coating on magnesium. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 324, 393–398. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2014.10.144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shahzad K.; Radwan A. B.; Fayyaz O.; Shakoor R. A.; Uzma M.; Umer M. A.; Baig M. N.; Raza A. Effect of concentration of TiC on the properties of pulse electrodeposited Ni–P–TiC nanocomposite coatings. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 19123–19133. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.03.259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo H.; Leitch M.; Behnamian Y.; Ma Y.; Zeng H.; Luo J. L. Development of electroless Ni–P/nano-WC composite coatings and investigation on its properties. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2015, 277, 99–106. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2015.07.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira M. C. L.; Correa O. V.; da Silva R. M. P.; de Lima N. B.; de Oliveira J. T. D.; de Oliveira L. A.; Antunes R. A. Structural Characterization, Global and Local Electrochemical Activity of Electroless Ni–P-Multiwalled Carbon Nanotube Composite Coatings on Pipeline Steel. Metals 2021, 11, 982. 10.3390/met11060982. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Madram A. R.; Pourfarzad H.; Zare H. R. Study of the corrosion behavior of electrodeposited Ni–P and Ni–P–C nanocomposite coatings in 1M NaOH. Electrochim. Acta 2012, 85, 263–267. 10.1016/j.electacta.2012.08.061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi Ashtiani A.; Faraji S.; Amjad Iranagh S.; Faraji A. H. The study of electroless Ni–P alloys with different complexing agents on Ck45 steel substrate. Arabian J. Chem. 2017, 10, S1541–S1545. 10.1016/j.arabjc.2013.05.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]