Abstract

Ethylene, of which about 170 million tons are produced annually worldwide, is a fundamental C2 feedstock that is widely used on an industrial scale for the synthesis of polyethylenes and polyvinylchlorides. Compared to other alkenes, however, the direct use of ethylene for the synthesis of fine chemicals such as pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals is limited, probably due to its small and gaseous character. We, herein, report a new radical difunctionalization strategy of ethylene, aided by quantum chemical calculations. Computationally proposed imidyl and sulfonyl radicals can be introduced into ethylene in the presence of an Ir photocatalyst under irradiation with blue light-emitting diodes (LEDs) (λmax = 440 nm). The present reaction systems led to the selective incorporation of two molecules of ethylene into the substrate, which could be rationally explained by computational analysis.

Introduction

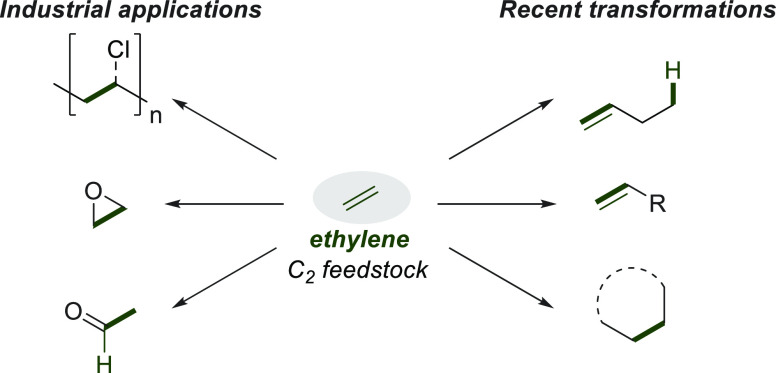

Ethylene (H2C=CH2) is a fundamental C2 feedstock that is usually prepared by naphtha cracking. The current state-of-the-art technology is based on the dehydrogenation of ethane extracted from shale gas. Approximately, 170 million tons of ethylene are produced per year worldwide, and these are used industrially for the synthesis of polyethylene and poly(vinyl chloride) in commercial quantities (Figure 1).1 Its major applications in the synthesis of small industrially relevant molecules are the preparation of ethylene oxide, acetaldehyde, and styrene.2 On the other hand, on a laboratory scale, the transition-metal-catalyzed incorporation of ethylene involving C–C bond-forming reactions, such as hydrovinylation, alkene metathesis, and cyclization, has been intensively studied over the last two decades.3

Figure 1.

Representative chemical transformations of ethylene.

However, the radical difunctionalization of ethylene has remained very limited, and only a few examples have been reported thus far;4,5 this dearth is probably due to difficulties associated with controlling the number of ethylene moieties that are incorporated in the products under radical conditions on account of the high reactivity of the resulting primary alkyl radicals. If ethylene could be difunctionalized without the undesirable ethylene polymerization, it would be a novel and practical strategy for the radical fixation of ethylene.

Results and Discussion

With this goal in mind, we adopted a theory-driven synthetic strategy for the radical difunctionalization of ethylene. First, we systematically screened potential heteroatom- and carbon-centered radicals by means of density functional theory (DFT) calculations using the artificial force induced reaction (AFIR) method with the GRRM program to determine what kind of radicals should be energetically feasible for a reaction with ethylene (Figure 2).6 The AFIR is a powerful calculation method that can automatically output reaction pathways using appropriate search options to specify reaction centers. In this project, the AFIR was used to search for the transition states (TSs) and equilibrium structures (EQs) as well as their connection via the reaction path.

Figure 2.

Calculated reactivities of various free radicals in the addition process to ethylene.

Among the calculated reactivities of sulfur-centered sulfonyl, sulfinyl, and thiyl radicals (Figure 2, entries 1–5), the p-toluenesulfonyl (Ts) radical exhibits the lowest activation barrier (ΔG‡ = 8.1 kcal/mol) with a negative ΔG (exothermic) during the radical-addition processes. Among the oxygen-centered radicals, the phenoxy radical exhibits a high ΔG‡, while the t-butoxy radical has a reasonably low ΔG‡ (9.9 kcal/mol) (entry 7). The reactivities of carbon-centered radicals were also calculated, and the results revealed that primary, secondary, and tertiary alkyl radicals exhibit moderately low ΔG‡ values (10.1, 9.9, and 9.7 kcal/mol, respectively) and highly negative ΔG values (entries 8–10). Then, we investigated the behavior of nitrogen-centered radicals (entries 11–18); imino radicals exhibit very high ΔG‡ values (∼18 kcal/mol) (entries 11 and 12), while amidyl and imidyl radicals show very low ΔG‡ (<4 kcal/mol) and highly negative ΔG values (up to −47.6 kcal/mol). Among the potential imidyl and amidyl radicals thus screened, the nitrogen-centered radicals generated from trifluoroacetoamide, succinimide, and phthalimide are expected to smoothly react with ethylene in an almost barrier-free fashion. The observed highly negative ΔG values lead to the stabilization of the resulting alkyl radicals, indicating that the reverse radical elimination can be neglected.

Encouraged by these positive computational results, we then turned our attention to the two most promising types of radicals, i.e., the imidyl and sulfonyl radicals with low ΔG‡ and negative ΔG values, for the radical difunctionalization of ethylene (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Our strategy for the difunctionalization of ethylene using imidyl and sulfonyl radicals.

The primary concern in the development of radical difunctionalization reactions of ethylene is experimentally generating the required heteroatom radicals. We considered halogen-attached succinimides such as N-chlorosuccinimide (NCS)/N-bromosuccinimide (NBS) and N-chlorophthalimide (NCP)/N-bromophthalimide (NBP) as potential imidyl-radical precursors under homolytic cleavage or one-electron-reduction conditions. For sulfonyl radicals, TsCl and TsCN were experimentally employed. In this paper, we successfully disclose new radical transformations of ethylene using these radical precursors under photochemical conditions. For most of the investigated cases, two molecules of ethylene were incorporated, and this unprecedented elongation was analyzed computationally.

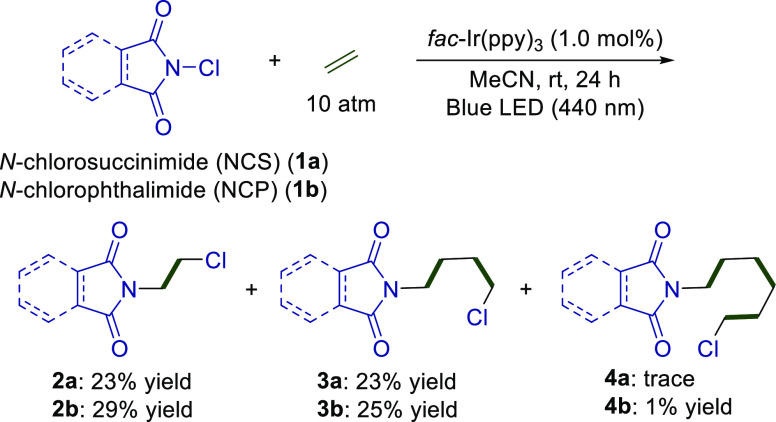

We first examined the reactions of NCS (1a) with ethylene (10 atm) in the presence of a 1.0 mol % Ir photocatalyst fac-Ir(ppy)3 under irradiation by a blue light-emitting diode (LED) (λmax = 440 nm) in MeCN (Scheme 1). After 24 h of irradiation, the expected difunctionalized product (2a) bearing succinimide and chloride on both sides of ethylene was obtained in a 23% yield. Moreover, 3a, which is derived from two molecules of ethylene, was also observed in a 24% yield, along with a trace amount of 4a, which is derived from three molecules of ethylene. A similar reaction profile was observed using NCP (2b) as a starting material (2b: 29% yield; 3b: 25% yield; 4b: 1% yield). The haloimidation of alkenes by NXS (X = halogen) is well known, but only one molecule of an alkene can be incorporated under UV irradiation.7 The reaction described herein is unique because two molecules of ethylene can be introduced simultaneously under very mild catalytic conditions using a blue LED. A reasonable explanation for the selective incorporation of two molecules of ethylene is discussed in Figure 5.

Scheme 1. Insertion of Ethylene into NCS and NCP under Photochemical Conditions.

Figure 5.

Mechanistic examination of the radical difunctionalization. (a) Trapping by NCP or NBP. (b) Reaction of IIIa with ethylene or NCP. (c) Reaction of IIIb arising from styrene with ethylene or NCP. (d) Reaction of IIIc arising from methyl acrylate with ethylene or NCP.

Subsequently, we investigated the corresponding bromo analogues NBS (5a) and NBP (5b). In both cases, difunctionalization proceeded smoothly, affording 6a and 6b, which contain only one molecule of ethylene, under blue-LED irradiation, even in the absence of a photocatalyst (Scheme 2). The reaction did not proceed without blue-LED irradiation, which excludes the possibility of a bromonium-mediated haloimidation.8 At present, we think that 5a and 5b can directly absorb blue light to homolytically cleave the N–Br bond.9 The product yield depends on the pressure of ethylene gas, i.e., higher pressure (10 atm) increased the yield to 85%.

Scheme 2. Insertion of Ethylene into NBS and NBP in the Absence of a Photocatalyst.

To increase the yield of 3b, which contains two molecules of ethylene, we undertook screening of the conditions (Table 1). The difunctionalization proceeded moderately with Ir photocatalyst 7a (entry 1); however, no reaction occurred in the absence of a catalyst, indicating that the catalyst can promote the cleavage of the N–Cl bond (entry 2). Using Ru photocatalyst 7b, the reaction became sluggish (entry 3). To our delight, when catalyst 7c, which bears electron-withdrawing groups on the ligand, was employed, the production of both 2b and 3b improved, whereby the yield of 3b was slightly higher than that of 2b (entry 4). Even when the reaction time was decreased to 30 min, the yield and the ratio of 2b/3b remained unchanged (entry 5). A comparison between the reported reductive potentials of 7a (−1.73 V), 7b (−0.81 V), and 7c (−0.89 V) indicates that 7a is the strongest reductant among these,10 but 7c was more efficient than the other catalysts. On the other hand, a comparison of the reported triplet-excited-state energies11 of 7a (58.1 kcal/mol), 7b (49.0 kcal/mol), and 7c (61.8 kcal/mol) indicates that 7c has the highest ability to transfer energy from the catalyst to the substrate. In combination with the fact that 5a and 5b could undergo radical difunctionalization without a catalyst, the Ir complex in this system acts as an energy-transfer catalyst, accelerating the homolytic cleavage of the N–Cl bond rather than promoting its reductive cleavage. After establishing a suitable catalytic system, we further screened the conditions to improve the yield of 3b. When the concentration was diluted to 0.05 M, the yield of 3b further improved to 51%, probably because more ethylene could be dissolved in the solvent MeCN (entry 6). In contrast, when NaBArF (BArF = tetrakis(3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)borate), which may change the counteranion of the photocatalyst to affect the product distribution, was used as an additive, the yield of 2b increased (entry 7). Although these yields were moderate, selective addition was possible depending on the reaction conditions employed (entry 6 vs entry 7).

Table 1. Screening Conditionsa,b.

Yields were determined via GC analysis using decane as an internal standard.

NaBArF (10 mol %) (BArF = tetrakis(3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)borate) was added.

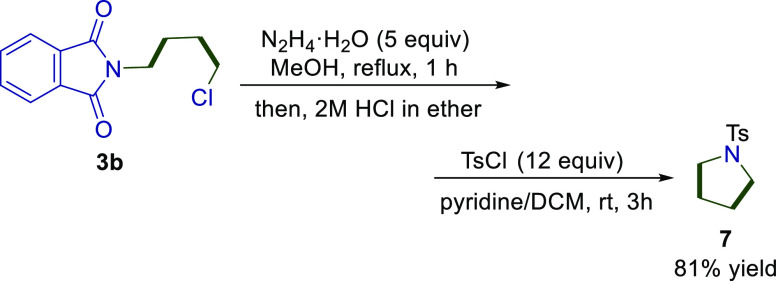

Product 3b, which contains two molecules of ethylene, was successfully transformed in a single step into a pyrrolidine motif through deprotection of the phthalimide moiety using N2H4·H2O, followed by cyclization (Scheme 3). After the resulting pyrrolidine was acidified with 2M HCl/Et2O due to its volatility, the protection was performed using TsCl in the presence of pyridine as a base. This nicely demonstrates that the pyrrolidine skeleton can be prepared from a nitrogen source and two molecules of ethylene. If the second molecule of ethylene could be replaced with another alkene, a variety of substituted pyrrolidine derivatives, which are often seen in pyrrolidine alkaloids,12 could be prepared efficiently.

Scheme 3. Conversion to Pyrrolidines.

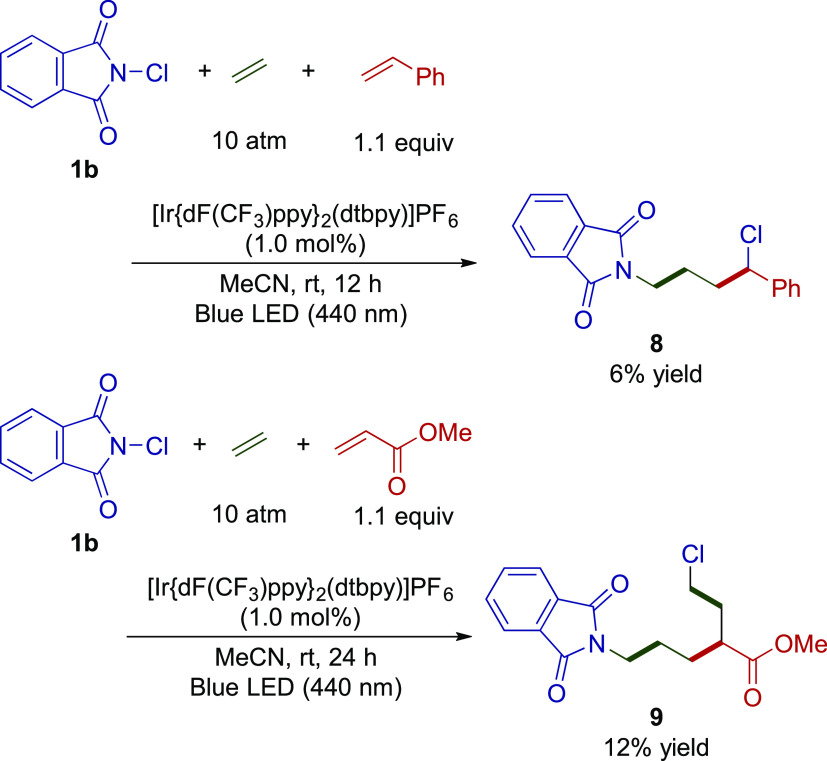

Accordingly, we investigated the possibility of replacing the second molecule of ethylene with other alkenes using DFT calculations with the AFIR method (Figure 4). We first calculated the ΔG‡ and ΔG values for the addition step of imidyl radical I derived from NCP (1b) to alkenes including ethylene, 1-hexene, styrene, methyl acrylate, and ethyl vinyl ether. Among these five alkenes, the activation energy of ethylene was ΔG‡ = 0.94 kcal/mol, indicating that the first insertion of ethylene seems promising. In contrast, the second addition of the resulting radical II derived from ethylene to alkenes exhibited different properties: styrene and methyl acrylate showed the lowest ΔG‡ values among the five alkenes (5.7 and 4.5 kcal/mol, respectively). It is difficult to predict the whole reaction process using DFT calculations precisely because the mechanism of the chloride-abstraction step is still elusive (vide infra). This rough estimation without the termination process motivated us to experimentally conduct the three-component reaction (3CR) of 1b, ethylene, and styrene or methyl acrylate. Since the differences in the activation energies were not very large, we expected that if the desired compound was generated, its production might be low.

Figure 4.

Radical additions to a variety of alkenes.

Initially, we conducted the 3CR of the imidyl radical derived from 1b, ethylene, and styrene (Scheme 4). The 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture suggested that the reaction generates several side products including 2b (6%), 3b (22%), phthNCH2CHClPh (5%), and styrene dimerized cyclobutene (trans/cis mixture: 10%);13 a closer inspection revealed that the expected 3CR product (8) was indeed generated in a 6% yield. As expected, the product yield was very low; however, our rough estimation successfully led to a new transformation of the imidyl radical toward two electronically similar alkenes. Furthermore, using methyl acrylate as the second alkene, the 3CR product 9 was obtained in a 12% yield together with 2b (16%) and 3b (23%). The generation of 9 was attributed to the further incorporation of ethylene at the α-position of the ester group, which was rationally explained by further DFT calculations (Figure 5).

Scheme 4. Reaction with Ethylene and Styrene.

To comprehend all of the reaction mechanisms described above, we examined the reactivities of all intermediates using DFT calculations. We first estimated the termination process of primary radical II arising from the reaction of ethylene with NCP (1b) via the radical chain mechanism, which is the generally accepted mechanism in previously reported haloimidations of alkenes (Figure 5a).7 The activation energy of trapping by 1b was found to be ΔG‡ = 13.4 kcal/mol. In comparison, the value for the insertion of a second molecule of ethylene (8.2 kcal/mol; Figure 4) is much lower, indicating that the second insertion of ethylene is expected to proceed predominantly. However, both 2b (incorporation of one molecule of ethylene) and 3b (incorporation of two molecules of ethylene) were obtained experimentally using 1b as a substrate (Scheme 1). This is because a radical–radical coupling might also be operative between the primary radical II and the chloro radical derived from the homolytic cleavage of the N–Cl bond triggered by the photocatalyst (vide supra). The radical–radical coupling is effectively barrierless (<1 kcal/mol), but it is not predominant in the reaction because the concentration of the chloro radical species is low. Therefore, the partial participation led to the formation of monoincorporation product 2b. Moreover, two chloro radicals, which are also present in low concentrations, may dimerize to form Cl2. As the activation energy of the trapping of II by Cl2 is very small (ΔG‡ = 1.9 kcal/mol; ΔG = −34.9 kcal/mol), this process is also possible. However, the homolytic cleavage of Cl2 by blue-light irradiation seems much more favorable.14

When 5b was employed as a substrate, the activation energy of the trapping by 5b after the ethylene insertion (ΔG‡ = 10.3 kcal/mol) is lower than that of 1b (ΔG‡ = 13.4 kcal/mol), indicating that the bromine abstraction proceeds more smoothly. Experimentally, 6b (incorporation of one ethylene) was obtained exclusively under blue-light irradiation (Scheme 2). The perfect selectivity toward the incorporation of one molecule of ethylene cannot be explained in terms of activation energies, as the activation energies for both possibilities are very similar (ΔG‡ = 8.2 kcal/mol and 10.3 kcal/mol), which strongly suggests the involvement of barrierless radical–radical coupling of the primary radical II and the bromo radical derived from the homolytic cleavage of the N–Br bond under blue-light irradiation. We also considered the side reaction of II with Br2, which also has a low energy barrier (ΔG‡ = 2.4 kcal/mol; ΔG = −12.8 kcal/mol).

Next, we calculated the reactivities of the radical insertion of IIIa arising from two molecules of ethylene toward ethylene and 1b (Figure 5b). Both additions have similar activation energies (ΔG‡ = 8.7 kcal/mol vs 9.2 kcal/mol). Considering the partial involvement of a radical–radical coupling process, trapping by 1b would be favored, which is consistent with the experimental result that the compound derived from three molecules of ethylene is a minor product (Scheme 1).

The reactivities of the radical insertion of IIIb arising from styrene toward both ethylene and 1b were also calculated (Figure 5c). Similar to the case of ethylene, both additions have very similar activation barriers (ΔG‡ = 15.1 kcal/mol and 15.8 kcal/mol). Considering the partial involvement of a radical–radical coupling process, trapping by 1b would be favored.

The reactivity of methyl acrylate-derived α-radical IIIc differs from that of styrene-derived radical IIIb. The reactivities of α-radical III toward both ethylene and 1b were calculated (Scheme 5d), and the activation energy of the ethylene insertion is ΔG‡ = 11.7 kcal/mol, while that of trapping by 1b is ΔG‡ = 20.2 kcal/mol. These values differ significantly, strongly suggesting that the chlorine abstraction is unproductive in this case, even when considering the radical–radical coupling. Therefore, electrophilic α-radical III should selectively react with ethylene to produce nucleophilic primary radical VI.

Scheme 5. Radical Difunctionalization Using Sulfonyl Radicals.

We also calculated the reactivities of VI toward ethylene and 1b to reveal that both additions have similar activation energies (ΔG‡ = 10.7 kcal/mol and 12.5 kcal/mol). Considering the partial involvement of a radical–radical coupling process, trapping by 1b would be preferable, which is consistent with the experimental result that 9 was obtained as the major product (Scheme 4).

Based on these calculations, we conclude that radical–radical coupling with a halogen radical and/or reaction with Cl2 could partially participate in the chlorine abstraction in addition to the proposed radical chain mechanism.7 Following this hypothesis, we can understand all of the ethylene difunctionalization reactions using 1b and 5b described in this paper.

Finally, we conducted the radical difunctionalization of ethylene with sulfonyl radicals (Scheme 5) using TsCl and TsCN as radical precursors.15,16 When TsCl was employed in the presence of the optimized Ir photocatalyst under blue-LED irradiation (λmax = 440 nm), difunctionalized product 12a, which contains two molecules of ethylene, was obtained in a 42% yield, together with 13a (incorporation of three molecules of ethylene) in a 20% yield. Moreover, when TsCN was used instead of TsCl as the radical precursor, 11b (incorporation of one molecule of ethylene) was obtained in a 19% yield along with 12b (incorporation of two molecules of ethylene) in a 39% yield. In the latter case, S–C- and two C–C-bond-forming reactions occur subsequently under mild conditions, which significantly strengthens our new methodology. In all of the examined cases, the products that bear two molecules of ethylene were the major products, irrespective of the counterpart of the Ts group.

Conclusions

In summary, we have developed a method for the radical difunctionalization of gaseous ethylene. Computational screening of potential radicals that could react with ethylene led to this new strategy, which is suitable for imidyl radicals and sulfonyl radicals. Using the radicals generated from NCS, NPS, NBS, NCP, TsCl, and TsCN, the radical difunctionalization of ethylene successfully proceeded under irradiation from blue LEDs in the presence of a photocatalyst. Most of the products thus obtained contained two molecules of ethylene. Furthermore, aided by computational estimation of the reactivities of the radical intermediates, we developed new 3CRs and 4CRs using styrene and methyl acrylate instead of the second equivalent of ethylene. These unprecedented reactions were rationalized using DFT calculations. Other radical difunctionalization reactions of ethylene are currently being investigated intensively in our laboratories, and the corresponding results will be reported elsewhere in due course.

Methods

In this study, the artificial force induced reaction (AFIR) method implemented in the global reaction route mapping (GRRM) program6a combined with the Gaussian 16 program17 was used, and all calculation results were obtained by the following process. The single-component artificial force induced reaction (SC-AFIR)6b,18 method with the kinetics-based navigation approach6c,19 (three reaction temperatures, 200, 300, and 400 K, were considered and the reaction time was set as 1 s) and the NoBondRearrange option (SC-AFIR is applied only to local minima that have the same bond connectivity with the initial structure) was adopted to obtain the equilibrium structures (EQs) and peak-top structures of the AFIR path (PTs) of radical additions to radical accepters (various alkenes or N-chlorophthalimide) with the UωB97X-D/Def2-SVPP, Grid=FineGrid, and SCFR (CPCM, solvent = CH3CN). The search was terminated after computing 20 paths. In the SC-AFIR search, the model collision energy parameter, γ, was set to 100 kJ/mol. After SC-AFIR calculation, the AFIR path having the lowest obtained PT was further optimized by the LUP method20,21 with the same level of theory to afford transition-state structures (TSs), which were the first-order saddle point and EQ structures before and after the radical addition. All EQs and TSs discussed in the text are local minima and first-order saddles, respectively, obtained by the final procedure and are not influenced by the artificial force.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by JST-ERATO (JPMJER1903), JSPS-WPI, and a Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Research (Exploratory) (21K1894501). T.M. thanks the Akiyama Life Science Foundation, the Ube Industries Foundation, the Fugaku Trust for Medical Research, and the Uehara Memorial Foundation for financial support.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.1c05102.

Experimental details, characterization data, and computational details (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

The version of this paper that was published ASAP November 5, 2021, contained an error in a label in the Table 1 header graphic. The corrected version was reposted November 30, 2021.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Ziegler K.; Holzkamp E.; Breil H.; Martin H. Das mülheimer normaldruck-polyäthylen-verfahren. Angew. Chem. 1955, 67, 541–547. 10.1002/ange.19550671902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Matsui S.; Mitani M.; Saito J.; Matsukawa N.; Tanaka H.; Nakano T.; Fujita T. Post-metallocenes: catalytic performance of new bis(salicylaldiminato) zirconium complexes for ethylene polymerization. Chem. Lett. 2000, 29, 554. 10.1246/cl.2000.554. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Eley D. D.; Pines H.; Weisz P. B., Eds.; Catalytic Oxidation of Olefins. Advances in Catalysis and Related Subjects; Academic Press Inc.: New York, 1967; Vol 17, pp 156–157. [Google Scholar]; b Smidt J.; Hafner W.; Jira R.; Sieber R.; Sedlmeier J.; Sabel A. The oxidation of olefins with palladium chloride catalysts. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1962, 1, 80–88. 10.1002/anie.196200801. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For selected examples of transition-metal-catalyzed ethylene incorporation via C–C-bond-forming processes, see:; a Rautenstrauch V.; Mégard P.; Conesa J.; Küster W. 2-Pentylcyclopent-2-en-1-one by catalytic Pauson-Khand reaction. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1990, 29, 1413–1416. 10.1002/anie.199014131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Jeong N.; Hwang S. H. Catalytic intermolecular Pauson-Khand reactions in supercritical ethylene. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 636–638. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c RajanBabu T. V. Asymmetric hydrovinylation reaction. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 2845–2860. 10.1021/cr020040g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Saini V.; Stokes B. J.; Sigman M. J. Transition-metal-catalyzed laboratory-scale carbon-carbon bond-forming reactions of ethylene. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 11206–11220. 10.1002/anie.201303916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Xia Y.; Ochi S.; Dong G. Two-carbon ring expansion of 1-indanones via insertion of ethylene into carbon-carbon bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 13038–13042. 10.1021/jacs.9b07445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected examples of the transition-metal-catalyzed difunctionalization of ethylene, see:; a Ohashi M.; Kawashima T.; Taniguchi T.; Kikushima K.; Ogoshi S. 2,2,3,3-Tetrafluoronickelacyclopentanes generated via the oxidative cyclization of tetrafluoroethylene and simple alkenes: A key intermediate in nickel-catalyzed C–C bond-forming reactions. Organometallics 2015, 34, 1604–1607. 10.1021/acs.organomet.5b00218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Ohashi M.; Shirataki H.; Kikushima K.; Ogoshi S. Nickel-catalyzed formation of fluorine-containing ketones via the selective cross-trimerization reaction of tetrafluoroethylene, ethylene, and aldehydes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 6496–6499. 10.1021/jacs.5b03587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Harper M. J.; Emmett E. J.; Bower J. F.; Russell C. A. Oxidative 1,2-difunctionalization of ethylene via gold-catalyzed oxyarylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 12386–12389. 10.1021/jacs.7b06668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Li J.; Luo Y.; Cheo H. W.; Lan Y.; Wu J. Photoredox-catalysis-modulated, nickel-catalyzed divergent difunctionalization of ethylene. Chem 2019, 5, 192–203. 10.1016/j.chempr.2018.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For the radical difunctionalization of ethylene, see:; a Joyce R. M.; Hanford W. E.; Harmon J. Free radical-initiated reaction of ethylene with carbon tetrachloride. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1948, 70, 2529–2532. 10.1021/ja01187a067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Asscher M.; Vofsi D. Chlorine-activation by redox-transfer. Part IV. The addition of sulphonyl chlorides to vinylic monomers and other olefins. J. Chem. Soc. 1964, 4962–4971. 10.1039/jr9640004962. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Haszeldine R. N.; Tipping A. E. Perfluoroalkyl derivatives of nitrogen. Part XVII. The reaction of N-bromobistrifluoromethylamine with olefins. J. Chem. Soc. 1965, 6141–6149. 10.1039/jr9650006141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Chang S.-C.; DesMarteau D. D. Addition reactions of N-bromoperfluoromethanamine with some olefins. J. Org. Chem. 1983, 48, 895–897. 10.1021/jo00154a034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Luning U.; McBain D. S.; Skell P. S. Free radical addition of N-bromoglutarimides and N-bromophthalimide to alkenes. Absolute and relative rates.. J. Org. Chem. 1986, 51, 2077–2081. 10.1021/jo00361a027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Singh S.; DesMarteau D. D. Chemistry of perfluoromethylsulfonyl perfluorobutylsulfonyl imide. Inorg. Chem. 1990, 29, 2982–2985. 10.1021/ic00341a026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Song L.; Luo S.; Cheng J.-P. Visible-light promoted intermolecular halofunctionalization of alkenes with N-halogen saccharins. Org. Chem. Front. 2016, 3, 447–452. 10.1039/C5QO00432B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; h Pan H.; Ge H.; He R.; Huang W.; Wang L.; Wei Y.; Sa R.; Wang Y.-J.; Yuan R. Photo-induced chloride atom transfer radical addition and aminocarbonylation reactions. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2019, 8, 1513–1518. 10.1002/ajoc.201900252. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Maeda S.; Ohno K.; Morokuma K. Systematic exploration of the mechanism of chemical reactions: The global reaction route mapping (GRRM) strategy using the ADDF and AFIR methods. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 3683–3701. 10.1039/c3cp44063j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Maeda S.; Harabuchi Y.; Takagi M.; Saita K.; Suzuki K.; Ichino T.; Sumiya Y.; Sugiyama K.; Ono Y. Implementation and performance of the artificial force induced reaction method in the GRRM17 program. J. Comput. Chem. 2018, 39, 233–251. 10.1002/jcc.25106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Sumiya Y.; Maeda S. Rate constant matrix contraction method for systematic analysis of reaction path networks. Chem. Lett. 2020, 49, 553–564. 10.1246/cl.200092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For UV-promoted haloimidation reactions, see:; a Day J. C.; Katsaros M. G.; Kocher W. D.; Scott A. E.; Skell P. S. Addition reactions of imidyl radicals with olefins and arenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978, 100, 1950–1951. 10.1021/ja00474a063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Lüring U.; Kirsch A. Imidyl radicals – Free-radical addition of N1-bromoimides to alkenes. Chem. Ber. 1993, 126, 1171–1178. 10.1002/cber.19931260517. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For the haloimidation of ethylene via an ionic mechanism, see:; Song L.; Luo S.; Cheng J.-P. Catalytic intermolecular haloamidation of simple alkenes with N-halophthalimide as both nitrogen and halogen source. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 5702–5705. 10.1021/ol402726d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima M.; Nagasawa S.; Matsumoto K.; Kuribara T.; Muranaka A.; Uchiyama M.; Nemoto T. A direct S0→Tn transition in the photoreaction of heavy-atom-containing molecules. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 6847–6852. 10.1002/anie.201915181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prier C. K.; Rankic D. A.; MacMillan D. W. C. Visible light photoredox catalysis with transition metal complexes: Applications in organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 5322–5363. 10.1021/cr300503r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strieth-Kalthoff F.; James M. J.; Teders M.; Pitzer L.; Glorius F. Energy transfer catalysis mediated by visible light: Principles, applications, directions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 7190–7202. 10.1039/C8CS00054A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson J.; Stevens K. Pyrrolizidine alkaloids: occurrence, biology, and chemical synthesis. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2017, 34, 62–89. 10.1039/C5NP00076A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagire S. K.; Hossain A.; Traub L.; Kerres S.; Reiser O. Photosensitised regioselective [2+2]-cycloaddition of cinnamates and related alkenes. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 12072–12075. 10.1039/C7CC06710K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For the UV-Vis spectrum of Cl2, see:; Maric D.; Burrows J. P.; Meller R.; Moortgat G. K. A study of the UV–visible absorption spectrum of molecular Chlorine. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 1993, 70, 205–214. 10.1016/1010-6030(93)85045-A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For a review on the reactivity of sulfonyl radicals, see:; Dong D.-Q.; Han Q.-Q.; Yang S.-H.; Song J.-C.; Li N.; Wang Z.-L.; Xu X.-M. Recent progress in sulfonylation via radical reaction with sodium sulfinates, sulfinic acids, sulfonyl chlorides or sulfonyl hydrazides. ChemistrySelect 2020, 5, 13103–13134. 10.1002/slct.202003650. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For the generation of tosyl radicals from TsCl or TsCN via photoredox catalysis, see:; a Wallentin C.-J.; Nguyen J. D.; Finkbeiner P.; Stephenson C. R. J. Visible light-mediated atom transfer radical addition via oxidative and reductive quenching of photocatalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 8875–8884. 10.1021/ja300798k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Liu X.; Cong T.; Liu P.; Sun P. Visible light-promoted synthesis of 4-(sulfonylmethyl)isoquinoline-1,3(2H,4H)-diones via a tandem radical cyclization and sulfonylation reaction. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016, 14, 9416–9422. 10.1039/C6OB01569G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Sun J.; Li P.; Guo L.; Yu F.; He Y.-P.; Chu L. Catalytic, metal-free sulfonylcyanation of alkenes via visible light organophotoredox catalysis. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 3162–3165. 10.1039/C8CC00547H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Hossain A.; Engl S.; Lutsker E.; Reiser O. Visible-light-mediated regioselective chlorosulfonylation of alkenes and alkynes: Introducing the Cu(II) complex [Cu(dap)Cl2] to photochemical ATRA reactions. ACS Catal 2019, 9, 1103–1109. 10.1021/acscatal.8b04188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Alkan-Zambada M.; Hu X. Cu-catalyzed photoredox chlorosulfonation of alkenes and alkynes. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 4525–4533. 10.1021/acs.joc.9b00238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Hell S. M.; Meyer C. F.; Misale A.; Sap J. B. I.; Christensen K. E.; Willis M. C.; Trabanco A. A.; Gouverneur V. Hydrosulfonylation of alkenes with sulfonyl chlorides under visible light activation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 11620–11626. 10.1002/anie.202004070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.; Trucks G. W.; Schlegel H. B.; Scuseria G. E.; Robb M. A.; Cheeseman J. R.; Scalmani G.; Barone V.; Petersson G. A.; Nakatsuji H.; Li X.; Caricato M.; Marenich A. V.; Bloino J.; Janesko B. G.; Gomperts R.; Mennucci B.; Hratchian H. P.; Ortiz J. V.; Izmaylov A. F.; Sonnenberg J. L.; Williams-Young D.; Ding F.; Lipparini F.; Egidi F.; Goings J.; Peng B.; Petrone A.; Henderson T.; Ranasinghe D.; Zakrzewski V. G.; Gao J.; Rega N.; Zheng G.; Liang W.; Hada M.; Ehara M.; Toyota K.; Fukuda R.; Hasegawa J.; Ishida M.; Nakajima T.; Honda Y.; Kitao O.; Nakai H.; Vreven T.; Throssell K.; Montgomery J. A. Jr.; Peralta J. E.; Ogliaro F.; Bearpark M. J.; Heyd J. J.; Brothers E. N.; Kudin K. N.; Staroverov V. N.; Keith T. A.; Kobayashi R.; Normand J.; Raghavachari K.; Rendell A. P.; Burant J. C.; Iyengar S. S.; Tomasi J.; Cossi M.; Millam J. M.; Klene M.; Adamo C.; Cammi R.; Ochterski J. W.; Martin R. L.; Morokuma K.; Farkas O.; Foresman J. B.; Fox D. J.. Gaussian 16, Revision C.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2016.

- Maeda S.; Harabuchi Y. Exploring paths of chemical transformations in molecular and periodic systems: An approach utilizing force. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2021, 11, e1538 10.1002/wcms.1538. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sumiya Y.; Maeda S. A reaction path network for Wöhler’s urea synthesis. Chem. Lett. 2019, 48, 47–50. 10.1246/cl.180850. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi C.; Elber R. Reaction path study of helix formation in tetrapeptides: Effect of side chains. J. Chem. Phys. 1991, 94, 751–760. 10.1063/1.460343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala P. Y.; Schlegel H. B. A Combined method for determining reaction paths, minima, and transition state geometries. J. Chem. Phys. 1997, 107, 375–384. 10.1063/1.474398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.