Abstract

The current study explores the parental perspectives of children with intellectual disabilities (ID) on the effectiveness of inclusive education in Greek mainstream schools. The participants were 83 parents, whose children had different degrees of ID and all of them were attending mainstream schools at the time of the study. They completed a questionnaire examining their perspectives with regard to (a) the most effective educational placement in mainstream schools (special class, mainstream class or co-teaching), (b) their satisfaction with the inclusive mainstream education, (c) their cooperation with the teachers, (d) the perceived benefits of their children’s educational placement and (e) their suggestions regarding the improvement of the inclusive educational model. Results indicated that most parents of children with ID would like their child to attend a mainstream class with a co-teaching arrangement. The perceived benefits are mostly related to the development of their children’s social skills. Significant considerations regarding cooperation with the teachers, lack of individualized information and guidance, administrative and organizational issues were expressed.

Keywords: parental perspectives, children with intellectual disabilities, inclusive education

Introduction

The inclusion of children with special needs in mainstream education has grown into a prevalent practice and has led to remarkable changes to schools conceptually and operationally (Gavish and Shimoni 2011). The embrace of inclusion has been boosted by its reported gains. Students with special educational needs are better able to learn, improve their academic skills and develop adaptive behaviour in inclusive settings in comparison to students educated in special schools (Alevriadou and Lang 2011, Dessemontet et al. 2012).

Nevertheless, the process towards an inclusive school environment is complex and the alterations and transformations involve multiple settings and stakeholders: parents, teachers, students and members of community. Parents have played a crucial role in supporting and promoting inclusion. In fact, they have been the advocates of the movement to include children with disabilities in mainstream education (De Boer et al. 2010). Thus, we cannot ignore the role of families in this process, since the family is the first field of intervention in dealing with diversity. In fact, the beliefs of families become very important in the process of educational reform. Attitudes, intentions and an inclusive or exclusive behaviour are built on these beliefs (Doménech and Moliner 2014). Furthermore, the in-depth knowledge and information that parents can provide to school about their child’s needs and how to be managed is both useful and helpful for teachers as well as support staff (Ashman 2015, Turnbull et al. 2015).

Most of the studies on the parents’ perceptions on inclusion show that families of children with special educational needs or disability support the inclusive educational model for many reasons (De Boer et al. 2010, Hu et al. 2018, Leyser and Kirk 2004, Lufti 2009). In fact, Leyser and Kirk (2004) concluded that parents identify social and emotional outcomes as one of the primary benefits of inclusive education. Additionally, the parents of children with mild intellectual disabilities have more positive attitudes towards inclusion than the parents of children with severe intellectual disabilities (Byrne 2013, Hilbert 2014).Parents of children with moderate-to-severe disabilities have identified academic and social benefits for children with disabilities educated in inclusive schools (Lui et al. 2017, Mann et al. 2016).

Although quantitative investigations into the parents’ perceptions have revealed their strong, and even increasing support for inclusive education, qualitative analyses of the parents’ satisfaction with inclusion have unveiled significant considerations regarding the classroom practices that promote inclusion. Parental concerns include social isolation (Lalvani 2015), negative attitudes as well as poor quality of instruction (De Boer et al. 2010) and untrained teachers in inclusive classrooms (Stevens and Wurf 2018). Parental reports verify the educational marginalization that is more likely to be tied in a disability label (Wendelborg and Tøssebro 2010). Lui et al. (2015) reported in their study how perceived social norm influences the attitude towards inclusion of parents of a child with special educational needs. Their findings suggest that the attitude towards inclusion of parents of children with special needs is positive if they perceive that stakeholders (teachers, principals, politicians, etc.) support inclusive education (Lalvani 2015).

Another major concern, identified by parents, has been the need for teachers to receive regular training in inclusive education. Significant concern about the teachers’ ability to support children with disabilities has been consistently noted (Leyser and Kirk 2004, Starr and Foy 2012, Whitaker 2007). Parents of children with disabilities have also reported that administrative paperwork, planning time, materials and personnel attitude influence student success in inclusive settings (Bennett and Gallagher 2013, Gurgur and Uzuner 2010). In their study, Ingólfsdóttir et al. (2018) found that parents raising young children with intellectual disabilities experienced welfare support services in Iceland often as fragmented and uncompromising, hard to reach and not in accordance with the needs of the family.

Parents who prefer separate placement also express deep reservations about the practical enactment of inclusion, especially for children with moderate-to-severe behavioural or cognitive difficulties. They are concerned about the readiness and potential of mainstream schools to manage and educate their child(De Boer et al. 2010, Duhaney and Salend 2000). Similarly, pedagogical barriers such as limited resources, insufficient teacher training in special needs, and absence of inclusive teaching practices render children with disabilities unable to deal with curricular demands (Pivik et al. 2002, Runswick-Cole 2008).

Families typically want frequent, informal, individualized and positive exchanges with educators (Turnbull et al. 2015). However, studies have found that parents of children with disabilities face difficulties in obtaining accurate and useful information (Brown et al. 2012, Ryan and Quinlan 2018). Dissatisfaction with the communication between parents and professionals has also been reported (Janus et al. 2008, O’Connor et al. 2005).

Another significant factor that plays a vital role in the promotion and enhancement of the inclusive educational model is the family–professional partnerships (Lendrum et al. 2015).Trusting family-professional partnerships arise when families and school professionals (principals, teachers, support staff) view each other as trustworthy allies and families have numerous opportunities for purposeful involvement in their children’s education and in the life of the school (Haines et al. 2013).Family–professional partnerships lead to enhanced student learning, positive behaviour and decreased achievement gaps between groups of students, including those with special educational needs and/or disabilities (Bryan and Henry 2012, Tschannen-Moran 2014). It should also be noted that family–professional partnerships improve educator efficacy and instruction and result in positive family outcomes which include enhanced satisfaction, understanding, social connections, development and parenting skills (Haines et al. 2013)

Although scientific studies on trusting family-professional partnerships demonstrate benefits for all stakeholders, schools appear not to nurture them (LaRocque et al. 2011). The latter can be attributed to the absence of a school-wide-organized approach to cultivating partnerships (Bryk 2010, Hoover-Dempsey et al. 2010). Teachers and professionals in general focus on simply informing parents, rather than building relationships (Mapp and Hong 2010). Different perceptions between professionals and families on what constitutes meaningful parent involvement may also hamper partnerships. Finally, educators receive limited guidance and support on how they can engage families in these relationships (LaRocque et al. 2011).

Parents of typically developing children are also part of the inclusive educational system and as such, their perceptions on inclusive education, either positively or negatively, influence its implementation. It has been shown that positive attitudes of parents with typically developing students are related to their knowledge of disabilities and their experience of inclusive education (De Boer et al. 2010, Rafferty and Griffin 2005). However, they appear to be less positive towards children with behavioral problems and severe cognitive impairment, compared with children with physical disabilities and sensory impairments. In addition, they have expressed concerns related to lower levels of instruction being used by the teacher, the modelling of inappropriate behaviour by peers, and the lack of teacher training in effectively managing inclusive classrooms (De Boer et al. 2010, Stevens and Wurf 2018).

As the implementation of inclusive practices is constantly growing, the evaluation of their effectiveness becomes of vital importance. Parents of children with special educational needs have been the advocates of inclusion and their beliefs play a major role in the educational reform towards inclusion. Thus, the aim of the present study was to explore the parental perspectives on inclusive education for children with ID.

Methodology

Research design

The primary variables of the present study, which were the multifaceted parents’ perspectives of children with ID, regarding their education in mainstream schools were identified and analysed with the implementation of a quantitative research design. In particular, the research questions were set as follows:

Which educational placement in mainstream schools (special class, mainstream class or co-teaching) do parents of children with ID consider to be the best educational setting?

To what extent are the parents of children with ID satisfied with the education of their children in mainstream schools?

To what extent do parents of children with ID cooperate with their children's teachers?

What do parents of children with ID consider to be the benefits of attending a mainstream school?

What are the parents’ suggestions regarding the improvement of their children's education in mainstream schools?

Data collection

The research was conducted between November 2017and February 2018. During this time, two researchers contacted the Principals of 62 schools, which were located in 4 regions of Northern Greece. The researchers informed the Principals for the purpose of the study and asked for the provision of the parents’ personal details as well as for their consent to mail the questionnaires. All participants were first fully written informed of the study and what is being asked of them, including the potential risks/benefits and exclusion criteria, in order to make a fully informed decision about whether or not to participate in the research and then a written consent was obtained from them. It was also emphasized that all data were confidential and anonymous in the final report. The questionnaire and consent form were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Board (University of Western Macedonia, Greece).

Hundred and eight questionnaires were sent to the parents of children with ID by post. The response was calculated at 76.9% (83 questionnaires).

Participants

The sample consisted of a total of 83 parents, whose children had different degrees of ID and all of them were attending mainstream schools in the school year 2017–2018.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the participants according to their sex, age and education level. It is noted that the vast majority of the parents were female, whose age was between 36 and 45 years old and they had a high school leaving certificate.

Table 1.

Characteristics of parents according to their sex, age and education level.

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 38 | 46.3 |

| Female | 44 | 53,7 |

| Total | 82 | 100 |

| Age | ||

| 25–35 years | 4 | 4.9 |

| 36–45 | 33 | 40.2 |

| 46-55 | 34 | 41.5 |

| 55 < | 11 | 13.4 |

| Total | 82 | 100 |

| Education level | ||

| Middle school | 22 | 26.8 |

| High school | 32 | 39.0 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 22 | 26.8 |

| Master’s degree | 6 | 7.4 |

| Total | 82 | 100 |

Table 2 shows the characteristics of students with ID, according to their sex and age. The vast majority of the students were boys and their age was between 7 and 12 years old.

Table 2.

Characteristics of children according to their sex and age.

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Boys | 69 | 84.1 |

| Girls | 13 | 15.9 |

| Total | 82 | 100 |

| Age | ||

| 2–6 | 14 | 17.2 |

| 7–12 | 55 | 67.1 |

| 13–18 | 9 | 11.0 |

| 19 < | 4 | 4.9 |

| Total | 82 | 100 |

Placement

As stated by the parents, in a total οf 82 students, 44 of them (53.7%) were in elementary school, 16 (19.5%) were in kindergarten, 13 (15.9%) were in secondary school and 9 (11%) attended technical education. In addition, according to the parents’ estimate, it was reported that 43 students (52.4%) had low verbal abilities, 23 (28.0%) had moderate verbal abilities and 16 (19.5%) had very low verbal abilities.

The degree of ID in relation to their placement (x2=13,385a, df = 6, p = 0.03 < 0.05) is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Educational Placement in relation to the degree of ID.

| Educational Placement | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Degree of ID | Special class N-% | Mainstream class with co-teaching N-% | Mainstream class N-% | Else N-% | Total N-% |

| Mild ID | 7–41.2% | 6–35.3% | 4–23.5% | 0–0% | 17–100% |

| Moderate ID | 11–20.7% | 24–45.3% | 17–32.1% | 1–1.9% | 53–100% |

| Severe ID | 5–41.7% | 1–8.3% | 4–33.3% | 2–16.7% | 12–100% |

| Total | 23–28.1% | 31–37.8% | 25–30.5% | 3–3.7% | 82–100% |

Description of the Questionnaire

The parents were asked to complete a questionnaire consisted of four sections. In the first section, parents were asked to provide detailed personal demographic information (sex, age and educational level). The rest of the questionnaire was composed of five-point Likert-type scale questions with response anchors (1 = the least, 2 = a little, 3 = moderately, 4 = quite a bit and 5 = very much). In the second section, parents were asked about their perceptions on educational placement issues (e.g. degree of satisfaction, intention of changing educational setting). In the third section, the parents’ perceptions regarding the benefits children with ID have from their attendance in mainstream schools were explored. Finally, in the fourth section, parents were asked about issues concerning co-operation with the teachers. An open-ended question was used to explore the parents’ suggestions regarding the improvement of their children's education in mainstream schools. The credibility and internal coherence of the questionnaire were tested by the Cronbach’s Alpha criterion (Cronbach’s Alpha: 0.801).

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis of the data was carried out with the statistical software SPSSv. 24.

The questionnaire was composed of nominal and ordinal variables obtained by using five-point Likert-type scale questions. Statistical analysis of the questionnaire included descriptive and inferential statistical methods.

In order to test the existence of independence between two qualitative variables (educational placement and level of ID) between groups, the χ2 independence test was applied through crosstabulation. Z- test was used to identify the differences in the percentages per category of variables with Bonferroni correction.

An exploratory factor analysis with varimax rotation was conducted in order to determine the number of factors obtained by the grouping of items. Criterion for selecting the number of factors were those with eigen values > 1.

Results

The parents reported that (a) 7 (43.8%) out of the 16 children with very low verbal abilities were placed in special class, (b) 21 (48.9%) out of 43 children with low verbal abilities were placed in mainstream class with co-teaching arrangement and (c) 10 (43.5%) out of 23 children with moderate verbal abilities were placed in mainstream class without co-teaching arrangement (χ2=11703 a, df = 5, p < 0.05).

With regard to the differences by parents’ educational level, a Z-test with Bonferroni correction at the 0.5 level was implemented. The majority of the parents of children with mild and moderate ID want a change in the educational placement, while 9 (75%) of the 12 parents of children with severe ID do not wish a change in their children’s educational setting.

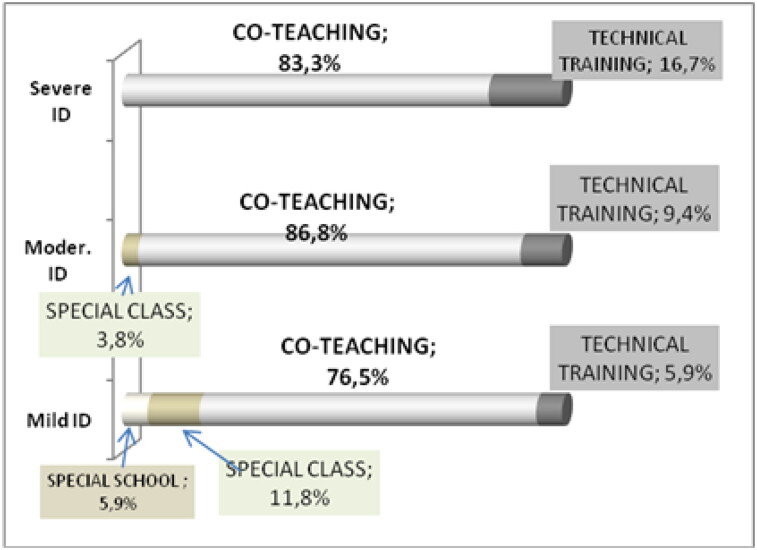

Our findings revealed that parents generally wish their intellectually disabled child to be placed in mainstream school (mean = 3.2, s.d. = 1.06). More specifically, most parents of children with mild ID responded ‘very much’, while half of the parents with severe ID responded ‘a little’. The observed differences, were statistically significant (χ2 = 32.408a, df = 8, p = 0.000).The vast majority of the parents (69, 84.1%), regardless of the degree of their children’s ID, want their child to be in a mainstream class with co-teaching arrangement. Figure 1 shows the preferred educational placement in relation to the degree of ID (x2 = 7.213 a, df = 6, p < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Educational placement by degree of ID.

Most of the parents of children with mild ID stated (χ2 = 9.139a, df = 8, p < 0.05) that they were moderately satisfied with their children’s educational placement (special class, mainstream class with co-teaching arrangement, mainstream class), while parents of children with moderate ID and severe ID replied that they were a little satisfied.

From the sample’s answers (Ν = 79, 3 missing), it is concluded that most parents (Ν = 62, 78.5%) evaluated the level of their cooperation with the teachers either as ‘moderate’ or ‘little’. Similar answers were given, regarding the level of cooperation in relation to their children’s degree of ID (χ2 = 14.900a, df = 8, p < 0.05).

The correlation between the perceived benefits and the child's educational placement in relation to the degree of ID was investigated as well. Parents responded to six questions related to: (1) relations and friendship with peers, (2) peers as behavioral models, (3) teachers, (4) peer-to-peer parents, (5) location of mainstream school, (6) curriculum and (7) other benefits.

An exploratory factor analysis with varimax rotation yielded three (3) factors:

Academic skills: reading, writing and math skills

Social skills: collaboration with peers, social interaction with peers, friendships with students without disabilities and verbal communication

Functional skills: self-care, autonomy and emotional skills

Questions with a load greater than 0.45 were considered to be grouped into a specific factor. Three factors explain the 72.67% of the total variance of the answers to questions (Table 4).

Table 4.

Factor analysis.

| Factors |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | F2 | F 3 | Mean | SD | |

| F1 Academic skills | |||||

| Writing | 0.842 | 3.74 | 0.93 | ||

| Reading | 0.831 | 3.68 | 0.83 | ||

| Math skills | 0.723 | 3.01 | 0.91 | ||

| F2 Social skills | |||||

| Collaboration with peers | 0.852 | 3.16 | 0.65 | ||

| Social interaction with peers | 0.762 | 3.23 | 0.71 | ||

| Friendships with students without disabilities | 0.799 | 3.10 | 0.70 | ||

| Verbal communication | 0.801 | 3.69 | 0.73 | ||

| F3 Functional skills | |||||

| Self-care | 0.920 | 3.34 | 0.81 | ||

| Autonomy | 0.846 | 4.03 | 0.93 | ||

| Emotional skills | 0.774 | 3.72 | 0.72 | ||

| Eigenvalues | 4.37 | 1,89 | 1.75 | ||

| Cronbach’s a | 0.973 | 0.844 | 0.762 | ||

| Variation per factor (%) | 30.43% | 23.12% | 19.12% | Total | 72.67% |

The factors of the questionnaire (academic, social and other benefits) were analyzed by using ANOVA repeated measures. The results showed statistically significant differentiation only for the academic skills factor. Parents of children with mild ID believe that the attendance in a mainstream school greatly helps the development of academic skills (mean = 4.16, s.d. = 1.18, p = 0.008), while the parents of children with moderate ID (mean = 2.78, s.d. = 0.86) and severe ID (mean = 2.39, s.d. = 0.84) evaluated the effectiveness with ‘moderately’ and ‘a little’.

From the respondents’ answers, it is concluded that most of the parents of children with mild and moderate ID consider their children's relationships with their peers to be of an important benefit (quite a bit and very much). However, 66.6% of the parents of children with severe ID responded ‘moderately’. The majority of the parents, without being differentiated by the degree of their children’s ID, responded that peers are behavioral models for their children. More than half of the parents of children with mild and severe ID replied that their children's teachers are an asset to their child's learning environment, but most of the parents of children with moderate ID responded with ‘moderately’ or ‘little’. Finally, the area, where the mainstream school was located, seemed to be related with the perceived benefits, while the curriculum was not considered to be an asset for most parents. There was no statistical significance (p > 0.05) of whether Peer-to-peer parents or the received services are an advantage of the educational placement for children with ID.

Participants were asked to make suggestions about the improvement in the education of children with ID in mainstream schools. Out of 71 parents (11 parents did not answer), 29 (41%) suggested less bureaucracy, 17 parents (24%) asked for solutions to administrative issues (e.g. timely recruitment of special education teacher, the same special education teacher to support the child with ID for two consecutive years), 15 parents (21%) suggested the improvement of the cooperation with stakeholders (e.g. mainstream teachers, special education teachers, schools principals, school advisor). Moreover, 7 parents (10%), suggested a curriculum suited for the needs of their children and 3 parents (4%) suggested more appropriate materials and educational resources. The differences between the observed and theoretical frequencies were statistically significant (χ2 = 89.472, df = 4, p < 0.001.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to explore the parental perspectives on the inclusive education for children with intellectual disabilities in Greece.

Preference of educational placement

Most parents responded that they would like their child to attend a mainstream class with a co-teaching arrangement and they perceive co-teaching as an attractive idea. The above finding is in line with previous studies that confirmed parents’ positive attitudes towards inclusive educational models (De Boer et al. 2010, Hu et al. 2018, Leyser and Kirk 2004, Lufti 2009).This belief stems from the fact that students' problems and difficulties (e.g. low academic performance, social isolation, etc.) are decreased, since there is a special education teacher working together with a general education teacher, who might not have the academic background and the skills required to meet the needs of all class students (Stevens and Wurf 2018).

Parents’ satisfaction related to education in mainstream schools

Another finding of the present study was that most of the parents of children with mild ID were found to be moderately satisfied with their children’s educational placement (special class, mainstream class with co-teaching arrangement and mainstream class), while parents of children with moderate ID and severe ID were a little satisfied Byrne 2013, Hilbert 2014Previous studies exploring the parents’ satisfaction with regard to inclusion have also reported significant considerations concerning the classroom inclusive practices (De Boer et al. 2010, Lalvani 2015, Lui et al. 2015, Janus et al. 2008, O’Connor et al. 2005; Runswick-Cole 2008). It seems that despite the changes and adjustments made in accordance with legislative interventions, as far as the inclusive education is concerned, the education of children with ID in mainstream schools is neither unobstructed nor without difficulties. The latter relates to issues concerning the development of the child's socio-emotional and academic skills. Barriers such as stereotypical views of disability and prejudiced behaviour have a significant negative influence on the emotional development of children with disabilities (De Boer et al. 2010; Duhaney and Salend 2000). In a study conducted by Koster et al. (2010), it was shown that placing a student with ID in mainstream school does not automatically ensure its social participation in the educational setting. The child may face difficulties in forming friendships and rejection by his classmates. Besides, social inclusion was defined by Cartledge and Johnson (1996) as a situation where each student is an accepted member of the group which he/she belongs to, has at least one active friendship and participates actively and equally in classroom activities. Therefore, social inclusion is associated with peer-friendly relationships, the acceptance of the peers, but also with students' self-understanding of the degree of the others’ acceptance.

Cooperation with the teachers

In the present study, most parents evaluated the cooperation with their children's teachers either moderate or low. The concept of cooperation involves mainly offering, the development of relationships, but also the achievement of common goals and outcomes of those working with each other on a common ground, such as school. Research data have shown that schools do not nurture inclusive practices (LaRocque et al. 2011). This finding may be due to reduced cooperative skills that teachers might have. Teachers and professionals in general focus on simply informing parents, rather than building relationships (Mapp and Hong 2010). Moreover, the absence of a school-wide systematic and structured approach to cultivating partnerships sets barriers on cooperation (Bryk 2010, Hoover-Dempsey et al. 2010). In addition, different perceptions between professionals and families on what constitutes meaningful parent involvement may also hamper partnerships. Finally, educators receive limited guidance and support on how they can engage families in these relationships (LaRocque et al. 2011).Moreover, one of the main problems that parents of children with ID report to face in our study, is the lack of information regarding their child’s education and the lack of guidance on how to support them. It has been proved that trusting family–professional partnerships result in positive family outcomes which include enhanced satisfaction, understanding, social connections, development and parenting skills (Haines et al. 2013). On the other hand, the in-depth knowledge and information parents can provide to school about their child’s needs and how to be managed is both useful and helpful for teachers as well as support staff (Ashman 2015, Turnbull et al. 2015). Parents of children with special educational needs play a dual role in educating their children. They become teachers and advocates of their children’s rights. This dual role requires them to be educated and informed on all issues related to the education of their children. However, previous studies have confirmed that parents of children with disabilities face difficulties in obtaining accurate and useful information (Brown et al. 2012, Ryan and Quinlan 2018).

Benefits of attending a mainstream school

The services provided by co-teaching to students with special educational needs are part of the inclusion process. Children benefit in a variety of ways, such as reduced stigma for students with special educational needs, increased level of understanding and respect by their peers as well as social acceptance in the classroom. Our results are consistent with the results of previous studies, reporting that parents perceive inclusion as a platform for children with developmental disabilities to interact, form friendships with typically developing peers and develop greater social skills (Mann et al. 2016, O’Connor 2007). Due to the aforementioned benefits of co-teaching, teachers, students and their parents recognize its importance as an inclusive practice (De Boer et al. 2010, Mulholland and O’Connor 2016). Moreover, Theoharis (2007) reports that the education of children with disabilities in mainstream schools is also a matter of social justice, since it enables students, who have been excluded from mainstream education, to co-exist and attend the same curricula with their peers. In addition, many parents of children with special educational needs consider co-teaching to be of great importance, since they believe that their children benefit to a great extent, when most of their education takes place in the context of mainstream education, while coexisting with other children without special educational needs (Cardona 2009).

Moreover, the parents who participated in the survey responded that the degree of development of their children's academic skills is related to the degree of their ID. The above finding can be explained, since the higher the degree of disability, the more difficulties the students face on issues such as (a) understanding the content in school textbooks, due to reduced reading ability, (b) activities that involve cognitive skills, (c) the amount of the new vocabulary and terminology in school textbooks, which makes it difficult for them to understand (Cawley and Parmar 2001, Ormsbee and Finson 2000) and (d) the school performance demands and marking especially at secondary schools (Mavropalias and Anastasiou 2016). Also, students with ID have certain characteristics that negatively affect their education in mainstream schools such as reduced cognitive functions and metacognitive skills (Hallahan and Kauffman 2006). Consequently, students with ID are less effective in using strategies and tend to have worse self-regulation at designing, monitoring and repeating during the learning process or problem solving (Kibby et al. 2004).

Parents’ suggestions

Furthermore, most parents responded that the decrease of bureaucracy and changes in administrative and organizational issues will foster a more effective educational setting for children with ID in mainstream schools. For example, in Greece and according to the latest law on special education (3699/2008), a child with ID can attend a mainstream school and receive co-teaching service, provided that the parent asks for a certificate from the Educational and Counselling Support Centres, each year, which they have to hand it in to the Principal of the mainstream school together with other documents and wait for a response (positive or negative) from the Greek Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs. Moreover, a significant percentage of parents responded that the Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs should have better planning with regard to the recruitment procedures of co-teachers. For example, several co-teachers are recruited two or three months later rather than September when the schools open. The above findings are in agreement with the results of previous studies reporting that parents of children with disabilities consider administrative paperwork, planning time, materials and personnel attitude to be negatively influential factors for student success in inclusive settings (Bennett and Gallagher 2013, Gurgur and Uzuner 2010, Lalvani 2015).

Additionally, parents stated that curriculum should be improved and mainstream schools should be equipped with appropriate materials and resources. Appropriate materials and resources are necessary to improve the conditions of placement and education of children with special educational needs in mainstream schools (Pivik et al. 2002, Runswick-Cole 2008). Although both recent laws in Greece on special education (Law 3699/2008 & Law 2817/2000) emphasize that appropriate means and services are essential for the objectives, set for the education of children with disabilities, to be achievable, the recent years of recession and austerity in Greece have hampered their provision.

Conclusion

Our study shows that although parents of children with ID prefer their child to attend school alongside with their typically developing peers, they express significant considerations concerning the effectiveness of the inclusive practices, such as the cooperation with the teachers, the provision of appropriate resources and materials as well as administration and organizational issues. On the other hand, the role of school effectiveness in the promotion of inclusiveness has been well documented, with emphasis given on teacher development and organisational change. Since parents have played a major role in promoting inclusion, educational policies should focus on training educators how to cooperate with the parents of children with ID and what inclusive practices to use. Besides, the gap between inclusive education policy and its implementation practice is not only due to the shortcomings of both legislative measures and financial resources, but it is also a matter of a policy related to the conflict of different ideologies and interests. Taking into account, the deeper economic and social inequalities, building trusty parent–teacher relationships will foster equity in inclusive mainstream education and will lead to desirable educational reforms.

Limitations

There are limitations to this study such as the sample size and the absence of the father’s perspective. Also, the method employed could not guarantee the generalizability of the findings, since participant selection was based on voluntary participation. In addition, the use of an alternative methodology, such as individual semi-structured interviews, would allow for a deeper insight into the individual parent attitudes. However, this study adds to the current literature, providing small scale, yet valuable parental perspectives on the inclusion of children with intellectual disabilities into mainstream educational settings in Greece.

Future research

Parental perceptions of children with disabilities can provide a deeper insight into the factors that families find most significant, thus facilitating the implementation of the inclusive educational model. However, parents of children with disabilities are not alone in the inclusive educational system. Parents of typically developing children are also part of the inclusive model and as such, their perceptions on inclusion positively or negatively influence its implementation. Thus, future research should more investigate the parents’ attitudes with typically developing children towards school inclusion, helping to identify the aspects that are important to families and the ones that can be improved. In addition, future research should investigate the school leaders’ perceptions on inclusion, since their attitudes are related to the shaping of an inclusive school culture. Finally, and most importantly, the perspectives of students with disabilities on inclusive education services should be explored as well as those of students without disabilities.

References

- Alevriadou, A. and Lang, L.. 2011. Active citizenship and contexts of special education: education for the inclusion of all students. London: Cice Central Coordination Unit. [Google Scholar]

- Ashman, A. 2015. Embracing inclusion. In: Ashman A., ed. Education for inclusion and diversity. (5th ed.). Melbourne: Pearson Australia, pp. 2–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, S. M. and Gallagher, T. L.. 2013. High school students with intellectual disabilities in the school and workplace: Multiple perspectives on inclusion. Canadian Journal of Education, 36, 96–124. [Google Scholar]

- Boer, A.A.D. and Munde, V.S.. 2014. Parental attitudes toward the inclusion of children with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities in general primary education in the Netherlands. The Journal of Special Education, 49, 179–187. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, H.K., et al. . 2012. Unmet needs of families of school-aged children with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 25(6), 497–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, J. and Henry, L.. 2012. A model for building school–family–community partnerships: principles and process. Journal of Counseling & Development, 90, 408–420. [Google Scholar]

- Bryk, A. S. 2010. Organizing schools for improvement. Phi Delta Kappan, 91(7), 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, A. 2013. What factors influence the decisions of parents of children with special educational needs when choosing a secondary educational provision for their child at change of phase from primary to secondary education? A review of the literature. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 13(2), 129–141. [Google Scholar]

- Cardona, C. M. 2009. Teacher education students' belief of inclusion and perceived competence to teach students with disabilities in Spain. Journal of the International Association of Special Education, 10, 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Cartledge, G. and Johnson, C. T.. 1996. Inclusive classrooms for students with emotional and behavioural disorders: Critical variables. Theory into Practice, 35(1), 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Cawley, J. F. and Parmar, R. S.. 2001. Literacy proficiency and science for students with learning disabilities. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 17, 105–125. [Google Scholar]

- De Boer, A. A., Pijl, S. J. and Minnaert, A.. 2010. Attitudes of Parents towards Inclusive Education: A Review of the Literature. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 25, 165–181. [Google Scholar]

- Dessemontet, R. S., Bless, G. and Morin, D.. 2012. Effects of inclusion on the academic achievement and adaptive behaviour of children with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 56(6), 579–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doménech, A. and Moliner, O.. 2014. Families beliefs about inclusive education model. Procedia – social and behavioral sciences, 116, 3286–3291. [Google Scholar]

- Duhaney, L. M. G. and Salend, S. J.. 2000. Parental perceptions of inclusive educational placements. Remedial and Special Education, 21, 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Gavish, B. and Shimoni, S.. 2011. Elementary school teachers’ beliefs and perceptions about the inclusion of children with special needs in their classrooms. Journal of International Special Needs Education, 14, 49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Gurgur, H. and Uzuner, Y.. 2010. A phenomenological analysis of the views on co-teaching applications in the inclusion classroom. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 10, 311–331. [Google Scholar]

- Haines, S. J., McCart, A. and Turnbull, A. P.. 2013. Family engagement within early childhood response to intervention. In: Buysse V. and Peisner-Feinberg E., eds. Handbook on response to intervention (RTI) in early childhood. New York: Brookes, pp. 313–324. [Google Scholar]

- Hallahan, D. P. and Kauffman, J. M.. 2006. Exceptional learners: An introduction to special education (10th ed.). Boston: Pearson Education, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Hilbert, D. 2014. Perceptions of parents of young children with and without disabilities attending inclusive preschool programs. Journal of Education and Learning, 3(4), 49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hoover-Dempsey, V. K., Whitaker, C. M. C. and Ice, L. C.. 2010. Motivation and commitment to family–school relationships. In: Christenson S. L. and Rechley A. L., eds. Handbook of Family Partnerships. New York, NY: Routledge, pp. 30–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, B. Y., et al. . 2018. Chinese parents’ beliefs about the importance and feasibility of quality early childhood inclusion. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 65(2), 163–182. [Google Scholar]

- Ingólfsdóttir, J. G., Egilson, S. T. and Traustadóttir, R.. 2018. Family-centred services for young children with intellectual disabilities and their families: Theory, policy and practice. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 22(4), 361–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janus, M., et al. . 2008. In transition: Experiences of parents of children with special needs at school entry. Early Childhood Education Journal, 35(5), 479–485. [Google Scholar]

- Kibby, M. Y., et al. . 2004. Specific impairment in developmental reading disabilities: A working memory approach. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 37(4), 349–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koster, M., et al. . 2010. Social participation of students with special needs in regular primary education in the Netherlands. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 57(1), 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Lalvani, P. 2015. Disability, stigma and otherness: Perspectives of parents and teachers. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 62(4), 379–393. [Google Scholar]

- LaRocque, M., Kleiman, I. and Darling, S. M.. 2011. Parental involvement: The missing link in school achievement. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 55(3), 115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Lendrum, A., Barlow, A. and Humphrey, N.. 2015. Developing positive school–home relationships through structured conversations with parents of learners with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND). Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 15(2), 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Leyser, Y. and Kirk, R.. 2004. Evaluating inclusion: An examination of parent views and factors influencing their perspectives. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 51(3), 271–285. [Google Scholar]

- Lufti, H. 2009. Attitudes toward inclusion of children with special needs in regular schools (a case of study of parents’ perspective). Educational Research and Review, 4, 164–172. [Google Scholar]

- Lui, M., et al. . 2015. Knowledge and perceived social norm predict parents’ attitudes towards inclusive education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 19(10), 1052–1067. [Google Scholar]

- Lui, M., Yang, L. and Sin, K.F.. 2017. Parents’ perspective of the impact of school practices on the functioning of students with special educational needs. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 64(6), 624–643. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, G., Moni, K. and Cuskelly, M.. 2016. Parents’ views of an optimal school life: using Social Role Valorization to explore differences in parental perspectives when children have intellectual disability. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 29(7), 964–979. [Google Scholar]

- Mapp, K. L. and Hong, S.. 2010. Debunking the myth of the hard to reach parent. In Christenson S. L. & Reschly A. L., eds. Handbook of School–Family Partnerships. New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mavropalias, T. and Anastasiou, D.. 2016. What does the greek model of parallel support have to say about co-teaching?. Teaching and Teacher Education, 60, 224–233. [Google Scholar]

- Mulholland, M. and O’Connor, U.. 2016. Collaborative classroom practice for inclusion: perspectives of classroom teachers and learning support/resource teachers. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20(10), 1070–1083. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, U. 2007. Parental concerns on inclusion: The Northern Ireland perspective. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 11, 535–550. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, U., McConkey, R. and Hartop, B.. 2005. Parental views on the statutory assessment and educational planning for children with special educational needs. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 20, 251–269. [Google Scholar]

- Ormsbee, C. K. and Finson, K. D.. 2000. Modifying science activities and materials to enhance instruction for students with learning and behavioral problems. Intervention in School and Clinic, 36(1), 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- Pivik, J., Mccomas, J. and Laflamme, M.. 2002. Barriers and facilitators to inclusive education. Exceptional Children, 69, 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, J. and Ha, A.S.. 2012. Inclusion in physical education: A review of literature. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 59(3), 257–281. [Google Scholar]

- Rafferty, Y. and Griffin, K.W.. 2005. Benefits and risks of reverse inclusion for preschoolers with and without disabilities: Perspectives of parents and providers. Journal of Early Intervention, 27(3), 173–192. [Google Scholar]

- Runswick-Cole, K. 2008. Between a rock and a hard place: Parents’ attitudes to the inclusion of children with special educational needs in mainstream and special schools. British Journal of Special Education, 35(3), 173–180. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, C. and Quinlan, E.. 2018. Whoever shouts the loudest: Listening to parents of children with disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 31, 203–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr, E.M. and Foy, J.B.. 2012. In parents’ voices: The education of children with autism spectrum disorders. Remedial and Special Education, 33(4), 207–216. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, L. and Wurf, G.. 2018. Perceptions of inclusive education: A mixed methods investigation of parental attitudes in three Australian primary schools. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Theoharis, G. 2007. Social justice educational leaders and resistance: Toward a theory of social justice leadership. Educational Administration Quarterly, 43(2), 221–258. [Google Scholar]

- Tschannen-Moran, M. 2014. Trust Matters: Leadership for Successful Schools. (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull, A. A., et al. . 2015. Families, professionals, and exceptionality: Positive outcomes through partnerships and trust (7th ed.) Boston: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Wendelborg, C. and Tøssebro, J.. 2010. Marginalisation processes in inclusive education in Norway: a longitudinal study of classroom participation. Disability & Society, 25, 701–714. [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker, P. 2007. Provision for youngsters with autistic spectrum disorders in mainstream schools: What parents say – and what parents want. British Journal of Special Education, 34(3), 170–178. [Google Scholar]