Abstract

Objective

To examine the impact of educational materials for chronic overlapping pain conditions (COPCs), the feasibility of delivering materials online, and to explore its impact on self-reported self-management applications at 3-month follow-up.

Design

Prospective cohort study

Setting

Online

Subjects

Individuals from a university-wide active research repository with ≥1 coded diagnostic COPC by ICD-9/10 in the medical record.

Methods

We determined the number of COPCs per participant as indicated by diagnostic codes in the medical record. Consenting participants completed self-report questionnaires and read educational materials. We assessed content awareness and knowledge pre- and post-exposure to education. Comprehension was assessed via embedded questions in reading materials in real time. Participants then completed assessments regarding concept retention, self-management engagement, and pain-related symptoms at 3-months.

Results

N = 216 individuals enrolled, with 181 (84%) completing both timepoints. Results indicated that participants understood materials. Knowledge and understanding of COPCs increased significantly after education and was retained at 3-months. Patient characteristics suggested the number of diagnosed COPCs was inversely related to age. Symptoms or self-management application did not change significantly over the 3-month period.

Conclusions

The educational materials facilitated teaching of key pain concepts in self-management programs, which translated easily into an electronic format. Education alone may not elicit self-management engagement or symptom reduction in this population; however, conclusions are limited by the study’s uncontrolled design. Education is likely an important and meaningful first step in comprehensive COPC self-management.

Keywords: Chronic Overlapping Pain Conditions, Pain, Chronic, Education, Fibromyalgia, Central sensitization

Chronic overlapping pain conditions (COPCs) are a highly prevalent subclass of 10 chronic pain conditions predominantly affecting females. The National Institutes of Health and US government now recognize COPCs as a set of conditions with a suspected shared etiology manifesting in a variety of body regions [1, 2]. The current 10 conditions recognized as COPCs by expert consensus include fibromyalgia (FM), chronic migraine, chronic tension type headache, irritable bowel syndrome, chronic low back pain, vulvodynia, interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome, encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, endometriosis, and temporomandibular joint disorder [2, 3].

In addition to pain that often varies in both intensity and location, additional COPC symptoms include fatigue, sleep difficulty, cognitive disturbance, and affective distress [1, 4]. Research to date has associated COPCs and this constellation of associated symptoms with a state of pain amplification resulting from peripheral or central sensitization [5]. Despite increased recognition of the role of central sensitization and COPCs on outcomes and symptom overlap, limited dissemination of this information has been offered to patients. For patients, pain that varies in intensity and location, in combination with associated functional limitations and psychological symptoms is distressing and interferes with daily functioning. Symptoms related to central sensitization (e.g., fatigue, cognitive difficulty) that result from complex pain states can be difficult for patients to understand and actively manage, particularly when no objective marker of pain exists. Patients often lack sufficient information or a framework for understanding their pain, and thus can become further distressed by a lack of “answers” or “visible” confirmation for their suffering [6].For some, the need for “objective proof of suffering” leads to a costly and perpetual referral cycle to specialists [7]. This can result in high utilization and low treatment satisfaction for patients, and associated breakdowns in patient-provider relationships [6–9]. Enhancing patients’ knowledge of the biological processes thought to underpin COPCs may provide a digestible rationale for the potential strategies often recommended to manage COPCs.

A key to the successful management of conditions involving central sensitivity includes the adoption of a self-management program [10].Such programs typically focus on non-pharmacological management of pain through lifestyle adjustments, coping skills acquisition and pain education [11].Self-management programs are generally delivered via individual interaction with a psychologist, and more recently through e- and m-health platforms, both in guided and unguided formats [12–16]. The inclusion of adequate pain education, in particular regarding pain mechanisms, has been determined as one of the top priorities in any pain psychological treatment program [17].

Over the past 20 years, pain education has evolved to focus toward altering a person’s conceptualization of their pain by emphasizing the process of pain in the body, including its function biologically and mechanistic underpinnings [18].The goal is to present the biological aspects of pain underlying the biopsychosocial approach to its management. Studies show that pain education programs alone have the potential to correct misconceptions about pain, reduce symptoms, and improve overall quality of life in chronic pain patients [19].When combined with physiotherapy, pain education has the ability to reduce disability in the short term, even when delivered in isolation [20].Importantly, a recent systematic review indicated that unguided interventions, including educational interventions, have the ability to improve short- and intermediate-term pain-related outcomes in individuals with chronic pain [14].

Common barriers to engagement in self-management practices include a lack of awareness and information about the availability of treatments, access to trained providers, and affordability [21].The Institute of Medicine (2011) referred to current deficits in pain education as inadequate diffusion of knowledge about pain to those who need it the most [22]. Currently, the Department of Health and Human Services is encouraging increased delivery of materials via electronic platforms to increase scalability of and access to low-burden, cost-effective pain education [21]. A recent meta-analysis [14] concluded that outcomes (effect sizes) on pain were slightly lower, but comparable between interventions delivered with and without the presence of an interventionist. The authors emphasized the potential for integration of eHealth platforms into treatment given their availability, low cost, and similar benefits. To date, evidence-based education to promote engagement in effective self-management programs for COPCs has not been developed—further, researchers are not yet clear on whether the information learned about unguided interventions will translate to this population [14]. As the research is rapidly evolving and new clinical trials emerge to treat COPCs, there is a need for COPC education that is clear, accessible, and relevant to patients. Having these materials available is timely clinically and for the conduct of future clinical trials.

This study aimed to conduct a pilot test of educational materials for COPCs via electronic delivery. We assessed patient understanding of COPCs, knowledge of central sensitivity as a mechanism of pain, and knowledge of self-management strategies for chronic pain after patients read the educational materials. As an exploratory aim, we sought to learn how brief online education could impact adoption of self-management strategies and any changes in symptoms over time. We hypothesized that following an online education intervention, patients would exhibit increased understanding of their condition and have a rationale for engaging in pain self-management. This study is the first in a larger vision to create standardized, scalable educational materials to operationalize in clinical trials for this class of pain conditions.

Methods

Study Procedures

All study procedures were approved by the institutional review board at Vanderbilt University Medical Center (#181628). This study occurred exclusively online and was facilitated through the use of REDCap [23].Eligible participants for study participation were identified from a large, university-wide active research database. This database contains medical records of over 18,000 individuals treated at a large academic medical center interested in research participation. Eligible study candidates were adults from this database with at least one diagnosed COPC in their health record later corroborated by self-report. Using an International Classification of Diseases, version 9 and 10 (ICD-9/ICD-10) code set informed by recent research [24] (see Supplemental Index), we prescreened records for potentially eligible adults with a diagnosis of at least one COPC defined as having two diagnostic codes associated with the same COPC from two separate medical encounters within the past 3 years. For example, an individual having medical visit associated with fibromyalgia (ICD-10 M79.7) on one occasion in 2017 and again in 2019 would be eligible for study participation. These potential study candidates were prescreened as study eligible and received an automated survey invitation requesting study participation. Those who met study eligibility criteria were then evaluated for any additional COPC codes in their health record .

Eligible individuals were contacted by automatic survey invitation offering the opportunity to participate in research. This automatic invitation included a unique online link to REDCap [23] to complete a brief set of validated self-report measures related to symptoms and functioning, and participants were then asked to read the educational materials. Prior to reading educational materials, we queried individuals about prior knowledge of the concepts presented. We then sought to assess whether patients learned from materials while reading. Thus, we embedded questions within the materials the patients were reading to assess real-time learning. Immediately following the online education, the original pre-test questions were re-administered. Participants also completed a second set of surveys at 3-months post-education to evaluate retention of material, current self-management application, symptoms, and functioning. In exchange for participation, we randomly selected 10 participants to receive a $100 gift card at both assessment time points.

Education Development and Distribution

Educational materials were developed in collaboration with experts in the areas of pain mechanisms, the study of COPCs, and intervention development. Content was informed by literature review, national patient advocacy and professional pain organizations, NIH-funded efforts supporting online self-management for pain [25], and current pain education groups conducted in person at both the University of Michigan and Vanderbilt University Medical Center. Educational material length was three pages and took participants approximately 15 minutes to read. The content covered information about COPCs and their mechanistic underpinnings, self-efficacy building strategies, and access to additional patient advocacy groups for support—all recognized as important domains for online self-management support for chronic pain [26].

The educational content addressed the following topics:

Definition and description of COPCs: a definition of COPCs, notation that these diagnoses often cannot be diagnosed by scans or blood tests, and a listing of all 10 conditions.

Matching mechanisms to type of pain being experienced (nociceptive vs neuropathic vs nociplastic/central): reviewed three types of pain, differentiating each type as pain caused by damage to the tissue, damage to nerves, or how the brain processes pain and providing associated examples.

A description of common signs and symptoms of central pain, including widespread pain in varying day-to-day intensity and location, allodynia, hyperalgesia, extreme sensitivity to other sensations such as noise or smell, and changes in cognition, mood, and sleep.

A summarized description of the common nociplastic/central pain symptoms using “s.p.a.c.e” acronym—sleep, pain, affect, cognition, and energy [4].

Current treatments for central pain and COPCs, describing current treatments and medicines used to target s.p.a.c.e symptoms.

Factors that may worsen central pain and COPCs.

Self-management strategies for COPCs via “e.r.a.s.e” acronym—emotions, reflections, actions, sleep, and environment [27].This first began with a more detailed description of the relationship between the specific area (e.g., emotions and pain), and then some suggestions, tips, and methods of managing that particular area.

An index of further tools, resources, advocacy groups, and relevant readings. This included more reading on the topics introduced, links to additional self-management tools online such as mindfulness meditations and insomnia guides, and national patient advocacy groups associated with their respective COPC for condition-specific resources and community building.

Measures

Descriptive and Clinical Variables

Demographics: Participants completed a 15-item brief demographic questionnaire detailing age, gender, race, religious orientation, household income, the presence of a COPC diagnosis, age of symptom onset, and disability status adapted from previous investigations [28].

PROMIS-29 Profile Scale [29, 30]: The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System® (PROMIS®) was designed to develop, validate, and standardize item banks to measure key domains of physical, mental, and social health in chronic conditions. The PROMIS-29 Profile scale consists of 29 items asking about specific symptoms related to pain, fatigue, function, and physical and emotional health. These scales have been developed for use in epidemiological and clinical studies and validated across both healthy and medical populations, including adults with chronic pain [31].

Complex Multi-Symptom Inventory (CMSI) [32]: The CMSI is a 41-item symptom checklist of past year illnesses specific to COPCs and assesses both co-morbidities and overall symptom burden from these conditions. In this investigation we used the total score of the CMSI as an indicator of overall symptom burden [1, 32].

Fibromyalgia Survey Criteria [33]: the Fibromyalgia survey criteria is a 7-item questionnaire assessing modified 2010 American College of Rheumatology diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and includes a) an index of widespread pain (WPI) and b) an index of symptom severity (SS) via patient self-report. This survey was designed for both clinical and epidemiologic studies. The total score on this scale ranges from 0 to 31, with scores ≥ 13 indicating a high likelihood of fibromyalgia [33].

Variables Assessing Learning and User Experience

Learning and Impact Assessment: We created the following series of measures to assess for familiarity with designated concepts in real-time, participant experiences with educational materials, and acquisition of new concepts. All questions below were developed specifically for this investigation.

Application and learning questionnaire: Before reading the educational materials, immediately after reading, and at 3-month follow-up participants rated their knowledge and understanding of concepts presented in the educational materials provided in 6 questions using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = “Completely Disagree,” 7 = “Completely Agree”). These questions assessed participant awareness of COPCs, understanding of central pain, knowledge of central pain symptoms, and awareness of self-management tools that can assist in pain management. Two additional questions assessed a participant’s current application of self-management tools to manage pain and level of communication with their medical provider about COPCs and self-management.

Content understanding questionnaire: when reading the educational materials, participants completed four content understanding questions in real-time, while reading. These questions were delivered in multiple choice format, embedded into the reading document to assess whether participants understood content as they read it.

User experience questionnaire: After reading, participants completed a 7-item questionnaire rating education relevance, clarity, novelty, helpfulness and satisfaction with the information they received in terms of length and content. Four items pertaining to item relevance, novelty, helpfulness and clarity were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “not [relevant],” 5 = “very [relevant]”). Three additional questions evaluated content satisfaction including one 7-point Likert scale item to assess satisfaction with content length (1 = “very poor,” 7 = “exceptional”) followed by two dichotomous items asking if participants wished to view more or less information on a particular topic, with the option of providing qualitative feedback. We report results of questions regarding relevance, clarity, novelty, and helpfulness and intend to use questions related to content length to inform any changes to materials in future studies.

Statistical Analysis

Table 1 details administration of all assessments across timepoints. To evaluate understanding of content, we assigned participants a passing score if they correctly answered at least 3 of 4 content understanding questions. Questions with multiple elements as a correct answer were marked correct if participants correctly answered all elements of the question. We also summed partially correct answers to establish the percentage of correct answers across all questions, in addition to the percentage of individuals who obtained passing scores. To test whether participants learned from the reading material, we compared pre- and post-education scores on a 7-point Likert scale from 6 application and learning questions (Table 3) using t-tests. Retention was evaluated by assessing the same questions post-education and at 3-month follow-up. To investigate whether there was a change in self-management engagement post-education we used t-tests to compare individuals’ reports of self-management application after reading materials with follow-up. To investigate whether pain-related symptoms changed after receiving education such as alterations in mood, functioning, and sleep, we used t- tests to compare PROMIS-29 T-scores from pre-education to follow-up (Table 4). We did not adjust for multiple comparisons across tests so that the strength of the results might be interpreted separately for each question.

Table 1.

Distribution of measures across timepoints before, during, and after receiving educational materials

| Outcome | Pre-Education (T0) | During Education | Post-Education (T1) | Follow-Up (T2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | x | … | … | … |

| CMSI | x | … | … | x |

| Fibromyalgia Criteria (WPI +SS) | x | … | … | x |

| PROMIS-29 | x | … | … | x |

| Learning and Application Questionnaire | x | … | x | x |

| Content Understanding | … | x | … | … |

| User Experience | … | … | x | … |

Table 3.

Learning and retention of concepts and self-management application following COPC education

| Pre-education (T0) | N (216) | Post-education (T1) | N (182) | Follow-up (T2) | P-value (T0/T1) | P-value (T0/T2) | P-value (T1/T2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (216) | [Mean±SD] | [Mean±SD] | [Mean±SD] | ||||||

| Learning and retention of concepts | |||||||||

| I am aware of chronic overlapping pain conditions | 211 | 4.89 ± 2.00 | 207 | 6.42 ± 0.95 | 153 | 6.44 ± 0.86 | <.001 | <.001 | .737 |

| I understand what central pain is | 211 | 3.83 ± 2.05 | 207 | 6.38 ± 0.91 | 153 | 6.44 ± 0.76 | <.001 | <.001 | .609 |

| I know the symptoms of central pain | 211 | 3.49 ± 2.03 | 207 | 6.35 ± 0.92 | 153 | 6.44 ± 0.79 | <.001 | <.001 | .327 |

| I am aware of self-management (i.e., coping) tools I can use to manage symptoms of pain | 211 | 5.16 ± 1.58 | 207 | 6.32 ± 0.99 | 153 | 6.41 ± 0.89 | <.001 | <.001 | .47 |

| Self-management application | |||||||||

| I am currently applying self-management tools to manage pain | 211 | 5.00 ± 1.77 | 207 | 5.52 ± 1.54 | 153 | 5.71 ± 1.33 | <.001 | <.001 | .162 |

| I have communicated with my provider about COPCs and self-management | 211 | 4.23 ± 2.28 | 207 | 4.41 ± 2.14 | 153 | 4.41 ± 2.06 | .092 | .318 | .311 |

Tests for differences due to learning (comparisons of all timepoints). SD = Standard deviation. *Unadjusted P values from t-test; COPCs = chronic overlapping pain conditions.

Table 4.

Baseline and follow-up comparison of symptoms and functioning after education

| N (216) | Pre-Education [Mean ± SD] | N (182) | Follow-Up [Mean ± SD] | P-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PROMIS-29 | |||||

| Physical Function | 212 | 42.11 ± 8.96 | 169 | 41.64 ± 8.69 | .982 |

| Anxiety | 207 | 54.77 ± 9.90 | 173 | 54.23 ± 10.25 | .702 |

| Depression | 207 | 53.08 ± 9.67 | 168 | 52.78 ± 9.71 | .518 |

| Fatigue | 209 | 59.28 ± 10.39 | 170 | 59.55 ± 10.61 | .612 |

| Sleep | 207 | 51.34 ± 4.61 | 169 | 50.96 ± 5.17 | .219 |

| Ability | 211 | 45.27 ± 9.29 | 171 | 44.77 ± 9.44 | .398 |

| Pain | 172 | 50.88 ± 4.94 | 136 | 50.69 ± 5.04 | .455 |

| CMSI | |||||

| Total score | 212 | 13.40 ± 9.10 | 169 | 13.69 ± 9.62 | .768 |

| Fibromyalgia | |||||

| WPI + SS | 210 | 11.43 ± 5.88 | 173 | 11.79 ± 5.95 | .327 |

Comparison of PROMIS 29 T-scores, CMSI scale and Fibromyalgia scales at baseline prior to education and at follow-up. SD = Standard deviation.

Results

Demographic and Diagnostic Characteristics

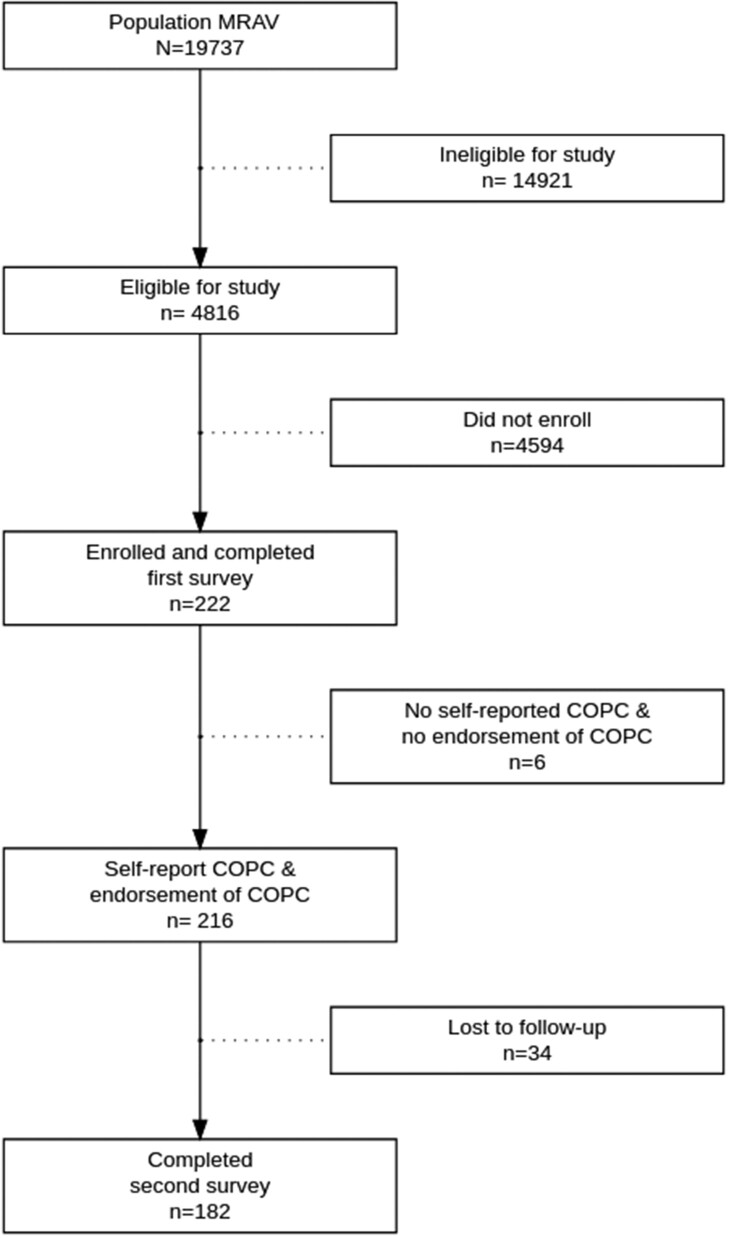

Based on our prescreening of the large hospital-wide database of research subjects, 4812 met inclusion criteria based on having a COPC diagnosis (Figure 1). We sent a survey link to those eligible, and 216 individuals consented to participate in the study in response to a single recruitment announcement. We assessed for any key differences between enrollees versus the large eligible pool of participants on age, sex, race, and diagnosis, and found no meaningful differences indicating a representative sample (e.g., all effect sizes [34] were trivial). When collecting demographic data, 6 individuals did not report having a COPC or the presence of chronic pain and were excluded from analyses (Figure 1). In addition to gathering information on participants having a COPC that permitted study inclusion (index diagnoses, included in Supplemental information), in those included in the sample, we also examined historical diagnoses of any ICD-9/10 codes given indicating additional COPC diagnoses for that individual, which are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram. MRAV= My research at Vanderbilt research repository; COPCs = chronic overlapping pain conditions.

Table 2.

Sample demographics

| Variable | N | Summary [Count (percentage)] |

|---|---|---|

| Age at enrollment | 214 | |

| Median (interquartile range) | 51.69 (40.79—62.20) | |

| Range | 21.07—85.04 | |

| Sex: Male | 216 | 42 (19.44) |

| Race: White | 216 | 195 (90.28) |

| Fibromyalgia | 216 | 102 (47.22) |

| Vulvodynia | 216 | 6 (2.78) |

| Temporomandibular disorder (TMJ) | 216 | 24 (11.11) |

| Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) | 216 | 51 (23.61) |

| Interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) | 216 | 12 (5.56) |

| Myalgic encephalopathy or chronic fatigue syndrome | 216 | 39 (18.06) |

| Endometriosis | 216 | 21 (9.72) |

| Chronic tension type headache | 216 | 10 (4.63) |

| Chronic migraine headache | 216 | 93 (43.06) |

| Chronic low back pain | 216 | 142 (65.74) |

| Number of COPC diagnosed | 216 | |

| Median (interquartile range) | 2.00 (1.00–3.00) | |

| Range | 1.00–7.00 |

COPC = chronic overlapping pain conditions.

Table 2 summarizes information gathered from the medical record and key demographic data collected at baseline. Participants were more likely to be older with a median age of 51.7 years old, female (80.6%), and White (90.3%). As assessed by ICD-9/10 codes, chronic low back pain was the most common diagnosis present among participants (65.7%), followed by fibromyalgia (47.2%) and chronic migraine headache (43.1%). Vulvodynia was the least common diagnosis present among participants (2.8%), along with chronic tension type headache (4.6%) and interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) (5.6%). Participants reported widespread pain and symptom severity and overall reduced physical function on the PROMIS-29.

The median number of COPCs diagnosed in the medical record was 2. Females were more likely to have multiple COPC diagnoses (median = 2, interquartile range [IQR] [1–3] vs median = 1, IQR [1,2]). The number of COPCs diagnosed ranged from 1 to 7 with a greater number of overlapping conditions being associated individuals who were younger (see Figure 2). For context, an individual with seven diagnosed COPCs had a median age 20 years younger than a person with one diagnosed COPC (median age = 35.26 vs 54.34 years). Figure 3 shows the unique diagnostic combinations in this sample. Although large variability existed within diagnostic clusters, the most frequent co-occurring diagnostic combinations were fibromyalgia and low back pain (N = 70, 32.4%), and chronic migraine and low back pain (N = 58, 26.9%). A fibromyalgia diagnosis was documented in the health record in 47.2% of our sample. Using our assessment measures, we also had the opportunity to examine how a fibromyalgia diagnosis compared to meeting epidemiological diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia. When comparing the presence of an ICD-coded fibromyalgia diagnosis in the sample to 2011 ACR epidemiological criteria, over 30% of the sample met the ACR fibromyalgia criteria without having a formal ICD diagnosis on record ((Table 5).

Figure 2.

Boxplot comparing number of COPCs diagnosed by age. COPCs = chronic overlapping pain conditions.

Figure 3.

Upset plot illustrating all possible unique combinations of COPCs. IC/BPS = interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome; TMJ = temporomandibular joint; IBS = irritable bowel syndrome. There are 65 total unique combinations of diagnoses present in patients. The most common unique condition is chronic back pain, with 31 (14.4%) patients diagnosed. The second most common unique condition is chronic migraine, with 22 (10.2%) patients diagnosed, followed by 13 (6.0%) patients being diagnosed with both chronic migraine and chronic back pain. Fibromyalgia is the next frequent diagnosis, with 12 (5.6%) patients having fibromyalgia and chronic back pain and 11 (5.1%) patients having only fibromyalgia. The set size on the left side of the plot displays the total number of present diagnoses. A total of 142 subjects have been diagnosed with chronic back pain, making it the most frequent diagnosis among participants, followed by fibromyalgia (n = 102) and chronic migraine (n = 93).

Table 5.

Epidemiological versus diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia

| Meet FM Criteria |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||

| N | (N = 109) | (N = 88) | Test Statistic | |

| Fibromyalgia from ICD | 216 | Χ21 = 26.98, P < .012 | ||

| No | 74/109 (67.89) | 27/88 (30.68) | ||

| Yes | 35/109 (32.11) | 61/88 (69.32) | ||

Comparison of those who meet criteria for fibromyalgia from the FM survey versus those actually diagnosed with an ICD-9 or ICD-10 code of fibromyalgia. Fibromyalgia (FM), International Classification of Diseases—9th/10th edition (ICD).

Patient Understanding, Learning, and Retention of COPC Education Materials

Comprehension of materials: While reading educational material, all participants completed four embedded questions in real-time assessing understanding of content as they read it—essentially in the form of a “pop quiz.” While reading materials, 190 of 216 participants (88%) passed the questionnaire surveying content understanding. When rating their experiences with the educational materials after having read them, 93% of respondents indicated that the information had some degree of novelty to them.

Learning from materials: We queried all participants about previous knowledge of core concepts in the COPC educational materials before and immediately after reading. Doing so allowed us to assess baseline knowledge of concepts presented and immediate learning after reading educational materials. This survey asked about prior knowledge of central pain, COPCs, available self-management strategies, and having patient-provider communication about these topics. Table 3 indicates participant responses to these questions prior to (T0) and following (T1) educational materials. Per Table 3, participants indicated significantly greater knowledge of concepts post-education across most questions). The nonsignificant difference observed regarding communication with a provider about self-management was expected. The significant change in reported application of self-management tools post-education was likely affected by participants’ improved understanding and awareness of the concept of self-management after reading materials.

Retention of learning and application of self-management: To investigate whether participants retained learned information over time, we compared scores to questions addressing learning post-education (T1) and at 3-month follow-up (T2, Table 3). Of those who completed the follow-up survey (N = 182), results found no evidence for a change in comprehension, suggesting good retention of concepts over time. To assess whether reading educational materials may initiate application of self-management methods, we compared the question regarding reported self-management application post-education (T1) and at follow-up (Table 3). We did not find sufficient evidence that the online education alone served as an effective intervention as there was no change in reported self-management application at follow-up (i.e., P = .162). Compared to baseline, we also did not find a significant change in reported pain-related symptoms from PROMIS-29 T-scores including physical function, mood, fatigue, sleep, and pain at follow-up (Table 4). Overall symptom burden (CMSI) and fibromyalgia symptoms (widespread pain and symptom severity) both remained stable and unchanged (Table 4).

Patient User Experience

Study participants completed a questionnaire evaluating their experience of educational materials in terms of novelty, clarity, relevance, and helpfulness using a 5-point Likert scale. Regarding novelty, 93.6% of individuals endorsed materials having some degree of novelty, ranging from very new (28.9%), to new (24.6%), moderately new (20.2%), and slightly new (19.8%). Participants indicated high relevance of materials, rating them as very relevant (50.7%), relevant (32.9%), or moderately relevant (11.1%)––with only 3.8% of participants stating materials were slightly relevant or not relevant at all (1.5%). Regarding clarity, materials were rated as very clear (44.9%) or clear (43.0%) in most cases. Participants rated the helpfulness of materials at above average (51.0%) or excellent (33.0%) overall.

Discussion

The primary findings of this study suggest that patients understood these novel COPC educational materials, with 88% of participants demonstrating concept mastery as assessed while reading materials. The materials were experienced as novel, relevant, and helpful to most participants. After reading, participants exhibited significantly increased awareness and understanding of concepts, including symptoms and coping strategies in COPC management. As a second aim, we evaluated concept retention and whether COPC education affected engagement in self-management behavior and any associated symptom change at follow-up. At 3-month follow-up, participants showed similar understanding of concepts as after reading the materials, indicating retention of learned material. However, despite retaining knowledge of pain management concepts, there was not sufficient evidence that patients had initiated changes in their behavior consistent with self-management nor change in pain-related symptoms such as alterations in sleep, mood, reduced pain interference, or fatigue levels.

Our study results suggest that although highly relevant and informative, pain education alone may not be sufficient to elicit self-management application or symptom reduction in patients with COPCs. While participants reported increased awareness of self-management strategies and behavior after receiving educational materials, there was no significant change in reported self-management behavior or pain-related symptoms at 3-month follow-up We assessed individuals’ ratings of their own self-management application after reading educational materials and at follow-up. Although this variable appears to change in the time (∼15 minutes) it takes to read the materials from baseline response, this is likely a reflection of either demand characteristics or participants having a better understanding of the concept of self-management.

Study findings may be informed by those of other educational interventions for chronic musculoskeletal pain in using Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE), of which there are two recent systematic reviews. In 2019, investigators concluded that PNE is thought to have short-term benefits to disability, knowledge, catastrophizing, and fear avoidance with associated long-term decreases in healthcare utilization [20]; however, this review excluded all individuals with fibromyalgia, widespread pain, or systemic pain from study inclusion. A second review evaluated PNE when applied to a range of pain conditions (including chronic low back pain, chronic fatigue, and fibromyalgia among others). While overall findings were positive, subsequent analyses indicated that when compared to PNE combined with movement-based strategies, PNE only did not show any ability to decrease pain ratings [35]. Additionally, the investigations providing PNE that measured pain knowledge demonstrated similar patterns of knowledge acquisition without relation to pain or functional improvements. Both reviews indicate that education benefits are optimized when combined with physiotherapy.

The lack of symptom changes or initiation of self-management following online education may also reflect the importance of a provider’s presence for patients with COPCs. Recent studies comparing cognitive-behavioral and educational interventions for chronic pain have found that patients can have substantial and lasting gains in as little as four sessions [36, 37]. In both of these trials, although participants benefitted from education, patient satisfaction was lowest in the education condition when compared to those who had therapeutic contact. The guided and unguided educational interventions mentioned previously also tended to be longer than a single timepoint. It may be that future studies evaluating interventions for COPCs include the content of this education into a longer educational intervention (e.g., four sessions), use as an active control for single timepoint intervention, or consider integrating the material into a comprehensive self-management program as combined treatments have shown to be more effective in this population.

Although not a primary study focus, our finding that the number of COPCs diagnosed within the same individual decreases with age may warrant additional inquiry. Unlike many comorbidities which accumulate with age and time spent in a healthcare system, sample demographics indicated numbers of COPCs accrued by an individual correlate inversely with age. Increased COPCs may be an indication of severity in younger patients, as the total disease burden and functional impairment increases as conditions accumulate [38].The simplest reason for this may be that the natural history of nearly all COPCs is that these conditions often begin in childhood or adolescence, with the peak incidence and prevalence being in midlife and then declining prevalence and incidence later in life. Emerging research also suggests that individuals with higher numbers of diagnosed COPCs report more severe syndrome-specific symptoms and higher rates of psychosocial distress, which is also associated with lower levels of function [39, 40]. Further, research in specific COPCs, such as interstitial cystitis, notes that younger individuals present with worse symptoms and have higher rates of healthcare utilization (although COPCs themselves were not measured in these studies) [41, 42]. Another potential explanation is that younger individuals may seek care at higher rates in this population. Historically, individuals with conditions having no observable pathology report stigmatization and invalidation by providers leading to withdrawal from care [43]. Therefore, future research could explore how healthcare seeking behaviors and symptom patterns may vary as a function of age in this population.

Study Strengths and Limitations

Our study is the first to formalize educational materials for COPCs and pilot test delivery online. The study had excellent participant retention for its online-only design, with 84% of subjects participating in the 3-month follow-up assessment. The educational materials were well-received by participants, who understood them, demonstrated learning, and acknowledged their relevance and novelty. Assessing the impact of the education on symptoms and self-management behavior over time is limited by our study’s uncontrolled design, where study rigor would improve with randomization and a control condition. Participant responses may also have been affected by demand characteristics common in survey research and self-evaluation. While the use of an electronic delivery method can increase access to education at scale, it limits access to those who may not have readily available internet or feel comfortable using technology. This may have also led to some selection bias in our sample by our methods used, in other words, that individuals with more resources and motivation participated. Although we had a large sample to draw from, we were limited to enroll a finite number of individuals by the institutional review board and did not pursue additional recruitment beyond a single, automated electronic recruitment announcement distributed to study-eligible individuals. Our response rate (4.5% enrollment) to a single automated recruitment announcement is similar to that of other registry studies employing personalized internet-based survey invitations (4.7%) [43]; however, may also have contributed to selection bias in the sample by those with immediate availability and access comprising the sample.

Our sample consisted of predominantly white participants (∼90%); however, participants had a vast age range spanning young adults to the elderly (21–85 years old). Under ideal circumstances we would have actively measured self-management application through detailed observation, with multiple data points, as opposed to a single item on a self-report measure. Sample homogeneity raises concerns regarding generalizability of findings to diverse populations. We recommend continued iterative material development with participant feedback and ongoing assessment of understanding to ensure that educational materials translate across diverse populations.

Our study was designed to provide online education to individuals with COPCs, prompting us to work to best identify those who would likely benefit from new educational materials through an administrative dataset. The use of ICD codes to detect patients with specific medical conditions in administrative datasets has limitations. Our approach to first capture individuals with likely COPCs based on medical data, use multiple encounters within a specific timeframe, and confirm their presence by patients’ self-reporting having a COPC all act to increase the likelihood of a true positive of a COPC (to best target our audience for education delivery). This is also reflected in participants rating educational materials as highly relevant to them on self-report assessments. However, sensitivity is affected by individuals not receiving formal evaluation across all COPCs. Errors can occur in diagnostic coding that can lead to misclassification.

With COPCs in particular, individuals may meet diagnostic criteria for multiple conditions but undergo evaluation within a single medical subspecialty without further evaluation of additional COPCs. There is some indication of this possibility in our finding that an additional 30% of our sample met epidemiological criteria for fibromyalgia who did not have this diagnosis in any coded encounters in their medical record. Diagnostic coding practices can be influenced by cultural norms within a specialty or region and may not translate across systems. These encounters reflect medical care received by a patient in a single healthcare system. Thus, while coded diagnostic overlap characterizes our cohort, it is an incomplete picture that may benefit from additional data points (e.g., manual validation, patient/provider interviews). A task force at the National Institutes of Health is in the process of finalizing a clinical tool permitting self-evaluation across all 10 recognized COPCs [24]. Such a tool will enable future research in this area to better identify individuals with likely COPCs and the degree of diagnostic overlap in patients.

Conclusion

The purpose of this investigation was to create understandable, novel educational materials for patients with COPCs. The educational materials facilitated the teaching of key pain concepts in self-management programs, which translated easily in an electronic format. Although education is an important aspect of self-management strategies in treating pain, additional factors in therapeutic interactions, skill building, and support offered by comprehensive self-management programs may together facilitate self-management application and symptom reduction in patients with COPCs. Future investigations may examine the incorporation of these materials into existing comprehensive self-management interventions for individuals with COPCs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

This project was conducted with support from the Vanderbilt Patient Centered Outcomes Research Education and Training Initiative and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ 6K12HS022990-05), National Institute of Health (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases) awards K23 DK118118 and L30 DK118656, and by Vanderbilt University Medical Center CTSA award no. UL1TR002243 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent official views of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data are available at Pain Medicine online.

Conflicts of interest: Dr. Clauw has performed consulting for Pfizer, Lilly, Aptinyx, Lundbeck, Samumed, IMC, and Swing Therapeutics, and has received grant funding from Aptinyx. Dr. Williams is a consultant to Community Health Focus Inc. and to Swing Therapeutics Inc. All other authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Williams DA, Kratz AL.. Patient-reported outcomes and fibromyalgia. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2016;42(2):317–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Maixner W, Fillingim RB, Williams DA, Smith SB, Slade GD.. Overlapping chronic pain conditions: Implications for diagnosis and classification. J Pain 2016;17(9):T93–T107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Veasley C, Clare D, Clauw DJ, et al. Impact of chronic overlapping pain conditions on public health and the urgent need for safe and effective treatment: 2015 analysis and policy recommendations. Chronic Pain Research Alliance 2015.

- 4. Williams DA. Phenotypic features of central sensitization. J Appl Biobehav Res 2018;23(2):e12135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Harte SE, Harris RE, Clauw DJ.. The neurobiology of central sensitization. J Appl Biobehav Res 2018;23(2):e12137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Epstein RM, Shields CG, Meldrum SC, et al. Physicians’ responses to patients’ medically unexplained symptoms. Psychosom Med 2006;68(2):269–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McGowan L, Luker K, Creed F, Chew-Graham CA.. How do you explain a pain that can't be seen? The narratives of women with chronic pelvic pain and their disengagement with the diagnostic cycle. Br J Health Psychol 2007;12(2):261–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Page LA, Wessely S.. Medically unexplained symptoms: Exacerbating factors in the doctor-patient encounter. J R Soc Med 2003;96(5):223–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bouck Z, Calzavara AJ, Ivers NM, et al. Association of low-value testing with subsequent health care use and clinical outcomes among low-risk primary care outpatients undergoing an annual health examination. JAMA Intern Med 2020;180(7):973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Adams LM, Turk DC.. Psychosocial factors and central sensitivity syndromes. Curr Rheuma Rev 2015;11(2):96–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Roditi D, Robinson ME.. The role of psychological interventions in the management of patients with chronic pain. Psychol Res Behav Manag 2011;4:41–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Williams DA, Kuper D, Segar M, Mohan N, Sheth M, Clauw DJ.. Internet-enhanced management of fibromyalgia: A randomized controlled trial. Pain 2010;151(3):694–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Du S, Liu W, Cai S, Hu Y, Dong J.. The efficacy of e-health in the self-management of chronic low back pain: A meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 2020;106:103507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moman RN, Dvorkin J, Pollard EM, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of unguided electronic and mobile health technologies for chronic pain—Is it time to start prescribing electronic health applications? Pain Med 2019;20(11):2238–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eccleston C, Fisher E, Craig L, Duggan GB, Rosser BA, Keogh E.. Psychological therapies (Internet-delivered) for the management of chronic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; (2):Cd010152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Williams DA. Web-based behavioral interventions for the management of chronic pain. Curr Rheum Rep 2011;13(6):543–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sharpe L, Jones E, Ashton-James CE, Nicholas MK, Refshauge K.. Necessary components of psychological treatment in pain management programs: A Delphi study. Eur J Pain 2020;24(6):1160–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moseley GL, Butler DS.. Fifteen years of explaining pain: The past, present, and future. J Pain 2015;16(9):807–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Borneman T, Koczywas M, Sun V, et al. Effectiveness of a clinical intervention to eliminate barriers to pain and fatigue management in oncology. J Palliat Med 2011;14(2):197–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wood L, Hendrick PA.. A systematic review and meta‐analysis of pain neuroscience education for chronic low back pain: Short‐and long‐term outcomes of pain and disability. Eur J Pain 2019;23(2):234–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Department of Health and Human Services. Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force Report: Updates, gaps, inconsistencies, and recommendations. In. Online2019.

- 22.Institute of Medicine (US). Committee on advancing pain research care and education. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press (US; ); 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG.. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap): A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42(2):377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schrepf A, Phan V, Clemens JQ, Maixner W, Hanauer D, Williams DA.. ICD-10 codes for the study of chronic overlapping pain conditions in administrative databases. J Pain 2020;21(1-2):59–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Williams DA, PainGuide. 2020; Self-management website for general pain management and COPCs. Available at: http://painguide.com (accessed June 1, 2020).

- 26. Vasudevan V, Moldwin R.. Addressing quality of life in the patient with interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome. Asian J Urol 2017;4(1):50–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Williams DA. Foundations in Pain Management: Biopsychosocial issues. Paper presented at: MI-CCSI Pain Management Training Conference 2017; Grand, Rapids, MI.

- 28. McKernan LC, Johnson BN, Crofford LJ, Lumley MA, Bruehl S, Cheavens JS.. Posttraumatic stress symptoms mediate the effects of trauma exposure on clinical indicators of central sensitization in patients with chronic pain. Clin J Pain 2019;35(5):385–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Amtmann D, Cook KF, Jensen MP, et al. Development of a PROMIS item bank to measure pain interference. Pain 2010;150(1):173–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, et al. The patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS): Progress of an NIH roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med Care 2007;45(Suppl 1):S3–S11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Deyo RA, Katrina R, Buckley DI, et al. Performance of a patient reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) short form in older adults with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pain Med 2016;17(2):314–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Williams DA, Schilling S.. Advances in the assessment of fibromyalgia. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2009;35(2):339–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, et al. Fibromyalgia criteria and severity scales for clinical and epidemiological studies: A modification of the ACR preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol 2011;38(6):1113–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vandekar S, Tao R, Blume J.. A Robust Effect Size Index. Psychometrika 2020;85(1):232–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Louw A, Zimney K, Puentedura EJ, Diener I.. The efficacy of pain neuroscience education on musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review of the literature. Physiother Theory Pract 2016;32(5):332–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jensen MP, Mendoza ME, Ehde DM, et al. Effects of hypnosis, cognitive therapy, hypnotic cognitive therapy, and pain education in adults with chronic pain: A randomized clinical trial. Pain 2020;161(10):2284–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lackner JM, Jaccard J, Keefer L, et al. Improvement in gastrointestinal symptoms after cognitive behavior therapy for refractory irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2018;155(1):47–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yunus MB. The prevalence of fibromyalgia in other chronic pain conditions. Pain Res Treat 2012;2012:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Krieger JN, Stephens AJ, Landis JR, et al. Relationship between chronic nonurological associated somatic syndromes and symptom severity in urological chronic pelvic pain syndromes: Baseline evaluation of the MAPP study. J Urol 2015;193(4):1254–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Crane AM, Levitt RC, Felix ER, Sarantopoulos KD, McClellan AL, Galor A.. Patients with more severe symptoms of neuropathic ocular pain report more frequent and severe chronic overlapping pain conditions and psychiatric disease. Br J Ophthalmol 2017;101(2):227–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chuang Y-C, Weng S-F, Hsu Y-W, Huang CL-C, Wu M-P.. Increased risks of healthcare-seeking behaviors of anxiety, depression and insomnia among patients with bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis: A nationwide population-based study. Int Urol Nephrol 2015;47(2):275–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Novi JM, Jeronis S, Srinivas S, Srinivasan R, Morgan MA, Arya LA.. Risk of irritable bowel syndrome and depression in women with interstitial cystitis: A case-control study. J Urol 2005;174(3):937–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sinclair M, O’Toole J, Malawaraarachchi M, Leder K.. Comparison of response rates and cost-effectiveness for a community-based survey: Postal, internet and telephone modes with generic or personalised recruitment approaches. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012;12(1):132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.