Abstract

Sexual function is a vital aspect of quality of life among adolescent and young adult (AYA, 15-39 years old) cancer survivors. Sexual function encompasses physical, psychosocial, and developmental factors that contribute to sexual health, all of which may be negatively impacted by cancer and treatment. However, limited information is available to inform care of AYA cancer survivors in this regard. This scoping review, conducted by the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) AYA Oncology Discipline Committee, summarizes available literature regarding sexual function among AYA cancer survivors, including relevant psychosexual aspects of romantic relationships and body image. Results suggest that, overall, AYA cancer survivors experience a substantial burden of sexual dysfunction. Both physical and psychosocial sequelae influence survivors’ sexual health. Interventions to support sexual health and psychosexual adjustment after cancer treatment are needed. Collaborations between the COG and adult-focused cooperative groups within the National Cancer Institute’s National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN) are warranted to advance prospective assessment of sexual dysfunction and test interventions to improve sexual health among AYA cancer survivors.

Keywords: AYA cancer, sexual function, sexual dysfunction, sexual health, cancer survivor

INTRODUCTION

Optimal sexual function is complex and requires normative interaction of multiple components including psycho-sexual development, physiology, romantic partnering, body image, and desire.1 Disruption of one or more of these components can lead to sexual dysfunction that can negatively impact the well-being of adolescents and young adults (AYA, 15-39 years old). For AYA cancer survivors who have completed cancer treatment, the risk for sexual dysfunction is high due to the physical and psychological consequences of both cancer and cancer treatments.2-5 Despite the prevalence of sexual dysfunction in this population, there are limited guidelines for oncology clinicians regarding how to screen for and address sexual dysfunction in this vulnerable population.

Adolescence and young adulthood represent a continuum of profound physical and psychosocial development that include physical maturation, formation of romantic relationships, and attainment of sexual milestones. Previous reviews of sexual function among AYA cancer survivors have focused primarily on the hormonal and physiological aspects of sexual function (e.g., erectile dysfunction, vaginal dryness)2,3,6,7,8; however, the influence of psychosocial factors (e.g., romantic relationships, body image) have not received comparable attention. Prior guidelines issued by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO)9 stem from literature focused on older adults with breast and prostate cancer and are limited in their acknowledgment of factors related to younger age and developmental stage. The Children’s Oncology Group (COG) Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancers delineate risk and screening recommendations for sexual dysfunction related to specific cancer therapeutic exposures10, but do not emphasize the various psychosocial and interpersonal factors that also represent aspects of sexual function.

To address these gaps, an expanded review of contemporary literature was undertaken by the Sexual Health Task Force of the COG AYA Oncology Discipline Committee. The COG is the world’s largest organization devoted exclusively to pediatric and adolescent cancer research aimed at improving survival and quality of life through studies of new and emerging cancer therapies, supportive care, and survivorship. Within the COG, the AYA Oncology Discipline Committee was formed to address compelling medical and psychosocial needs of AYAs with cancer.11 Recognizing that sexual health is an understudied AYA issue, the COG AYA Committee created the interdisciplinary AYA Sexual Health Task Force to evaluate the state of the science and care in sexual health and provide recommendations on salient research questions that are feasible and appropriate for addressing in a cooperative research group setting. Therefore, the purpose of this scoping review was to describe the prevalence and types of sexual dysfunction, and relevant psychosexual aspects of romantic relationships and body image among AYA cancer survivors (currently 15-39 years of age and previously treated for either childhood or AYA-onset cancer). The results will be used to (1) inform future research within the COG and possibly other adult-focused cooperative oncology study groups; and (2) lay a foundation for generating comprehensive sexual health guidelines and clinical tools for oncology providers who care for AYA survivors.

METHODS

As sexual functioning includes a myriad of conditions and assessments, a scoping review was conducted to fully capture the diversity of studies. Scoping reviews present a map of existing heterogeneous literature, most often on topics that are complex in nature, and are used to identify knowledge gaps in the literature and guide future research initiatives.12 For this review, we focused on sexual dysfunction, sexual desire, satisfaction, body image, and romantic relationships among post-treatment AYA cancer survivors (15 to 39 years of age) who were diagnosed with cancer in childhood, adolescence, or young adulthood (<39 years of age). The age range of 15 to 39 years is consistent with the definition of adolescent and young adult established in 2006 by the National Cancer Institute.13,14 This review focuses on AYAs who have completed cancer therapy; studies of on-treatment AYAs were not included because the acute side effects of active treatment are distinctive and preclude accurate comparisons with AYAs who have completed treatment.

Information Sources

Initially, a research librarian facilitated generation of search terms, which were subsequently reviewed and vetted by all authors. Preliminary searches were conducted on PubMed to ensure the search strategy would produce the desired results. Next, a comprehensive search was conducted in August 2018 of the electronic databases of PubMed, CINAHL, OVID MEDLINE, Embase, and PsycINFO. Combinations of the following terms were used to search all databases: child, OR young adult, OR adolescent, AND cancer survivorship, OR childhood cancer survivors, OR cancer, OR malignant neoplasms, AND sexuality, sexual behavior, OR physiologic sexual dysfunction, OR sexual development, OR sexual behavior, OR sexual partners, OR gonadal disorders/therapy, OR body image, OR sexual health, OR psycho-sexual, OR sexual quality of life, OR sexual intimacy, OR sexual satisfaction, OR romantic relationships. Additional articles were identified through review of individual article reference lists. A final search was conducted in May 2020 to identify newer articles.15

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were included if they (1) were published in peer-reviewed journals in English; (2) used quantitative, qualitative or mixed methods; (3) addressed the review question; (4) had a sample where >50% participants were currently aged 15-39 years old and previously treated for cancer; (5) published in 2006 or later, to align with the National Cancer Institute/Livestrong Young Adult Alliance pioneer publication of an AYA oncology national agenda that highlighted sexual health needs in this population14. If two studies relied on the same patient sample and same measures, the most recent publication was selected for inclusion.

Studies were excluded if they: (1) were focused primarily on fertility, fertility preservation or contraception or sexually transmitted infection prevention; (2) reported results for AYAs and older adults in aggregate such that outcomes for AYAs could not be delineated; (3) had a sample where > 50% were survivors currently > 39 years of age; (4) were case studies, review articles or commentaries, grey literature, and conference abstracts.

Data Analysis

Search results were compiled in Covidence© and duplicates were removed using Covidence© software.16 Following duplicate removal, two authors reviewed each abstract independently for inclusion. In the event of disagreement, a third author made the final decision. Pairs of authors then independently reviewed all full texts and determined whether they should be included in the final sample for extraction. Discrepancies between authors were resolved by the senior author G.Q. Authors G.Q and A.S developed the data abstraction form which included site of study, study method, summary of main finding, type of statistical analysis, study limitations and notes.

Quality Assessment

The quality of quantitative publications was assessed using the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies and the rating was determined based on sampling approach, participation rate, representativeness of study population, use of valid measures, and statistical approach.17 Quality assessment for qualitative and mixed methods studies was conducted using the Rapid Critical Appraisal Tools for a Qualitative or Mixed-Methods Study and the rating was determined based on design, sample, credibility, trustworthiness, and transferability.18 The lead author (B.C.) rated each publication according to the tool guidelines which are based on specific criteria that were used to make an overall quality categorization of poor/low, fair/medium, or good/high.

RESULTS

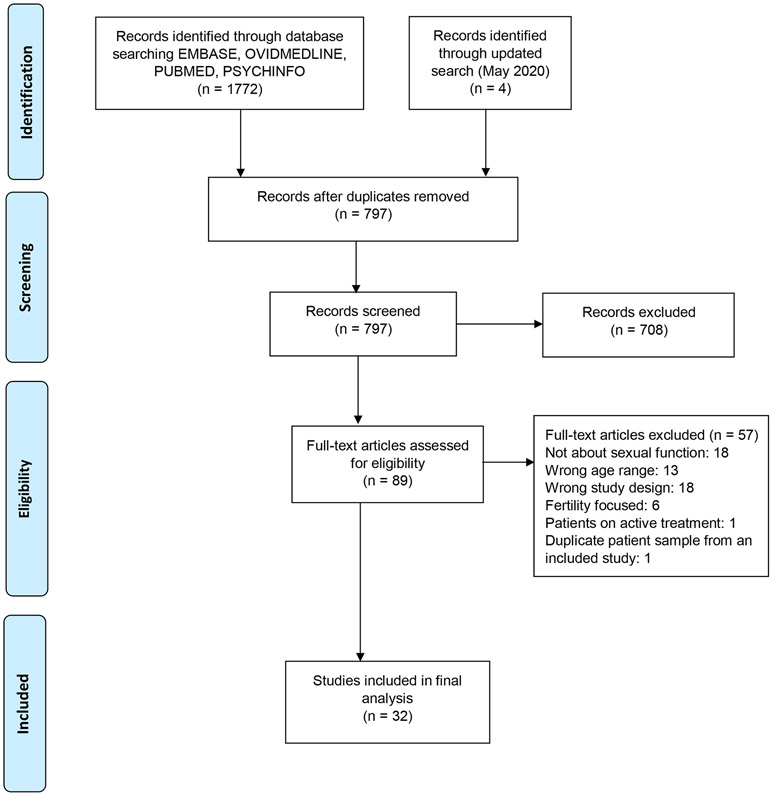

A total of 1772 articles were retrieved; after duplicates were removed, 793 articles remained (Figure 1). Of the 793, 706 articles were excluded for not meeting study inclusion criteria during the title and abstract review. The remaining 87 papers underwent full text review and of these, 57 papers were excluded. Reasons for exclusion of articles were the following: did not report outcomes on sexual function (n=18), reported ages in aggregate or outside the specified range (n=13), were a commentary, review article, or case report (n=18), focused solely on fertility (n=6), included patients on active treatment (n=1), or was a duplicate patient sample from an included study (n=1). The updated search (May 2020) yielded 4 new publications of which 2 met inclusion criteria. Ultimately, 32 studies were included in the final review of which 22 were quantitative studies, 7 qualitative studies, and 3 used a mixed methods approach.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of identifying literature

Most studies were quantitative and used a cross-sectional (n=20) or observational cohort (n=1) design. Only one quantitative study reported longitudinal data19. Of the 22 quantitative studies, the quality rating was good for 6 (27.3%) studies, fair for 12 (54.5%) studies, and poor for 4 (18.2%) studies. Of the 8 qualitative studies, quality was rated as high, medium, and low among 5 (62.5%), 2 (25.0%), and 1 (12.5%), respectively. Two studies were mixed methods, one rated high quality and the other rated medium quality. The quality ratings are presented in Supplementary Tables A1-A3; no publications were excluded based on quality ratings.

The studies included in this review represent geographically diverse survivors, in that half of the studies (n=16) were conducted in the United States, while the other half were conducted in Europe (n=11), Canada (n=4), and Australia (n=1). AYA-aged survivors of both childhood and AYA cancers are represented in this review; 19 studies included only participants who were diagnosed <21 years, two studies were focused on survivors who were diagnosed across childhood and young adulthood (e.g., 5-38 years of age)20,21, and the remaining 11 studies included participants diagnosed in adolescence and/or young adulthood (i.e., 15-39 years of age). Four studies included only males, 5 only females, and 23 included both male and female cancer survivors. There were two studies that focused on specific cancers (breast22 and gynecological21).

Three themes emerged as important concepts related to sexual health: 1) sexual dysfunction, including 1.a) prevalence of sexual dysfunction and 1.b) other aspects of sexual dysfunction, 2) relationship factors (e.g., relationship status, quality of romantic relationships), and 3) body image. Sexuality and sexual functioning are multi-faceted, and most studies assessed more than one concept.

Sexual Dysfunction

Sexual dysfunction was examined using various measures (Table 1), with sexual dysfunction reported as a primary outcome in 12 studies. Measures of overall sexual dysfunction included the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Sexual Functioning Scale19,23 and the similar Swedish Health-Related Quality of Life Scale (Swed-QUAL)24,25, the Life Impact Checklist26,27, the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI)21,28, the Derogatis Interview for Sexual Functioning Self-report29, the Brief Sexual Function Questionnaire for Men (BSFQ-M)30, the International Index of Erectile Function 31, the Sexual Function Questionnaire (SFQ) for Women32, and the Brief Index of Sexual Functioning for Women (BISF-W)30,32. Graugaard et al. included an item assessing self-reported problem with sexual function.33 Sexual dysfunction was also discussed by participants in qualitative studies.34,35

Table 1.

Study design, measurement, and outcomes of studies included in literature review.

| Publication | Design | Country | Type of cancer, age and number of participants |

Sexual Function Outcome(s) |

Measurement(s) | Main Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acquati et al., 2018 | Observational Cohort, longitudinal measures | United States | Survivors of various cancers 18-39 years of age N=123 |

Sexual Dysfunction | MOS Sexual Functioning Scale | 52% of participants reported sexual dysfunction |

| Barrera, Teall, Barr, Silva, & Greenberg, 2010 | Cross-sectional | Canada | Lower extremity bone tumors >16 years of age N=28 |

Desire, satisfaction, orgasm, enjoyment/pleasure, erection | Brief SFQ-M BISF-W |

Males reported better sexual function compared with females. Compared to survivors with a limb salvage procedure, survivors with a lower extremity amputation or rotationplasty reported better sexual function. |

| Self-perception | Harter Adult Self-Perception Profile | Survivors with amputation or rotationplasty had higher global self-worth compared with survivors of limb-sparing procedures. | ||||

| Bellizzi et al., 2012 | Cross-sectional | United States | Survivors of various cancers 15-39 years of age N=523 |

Sexual Function Sexual Dysfunction Body Image |

Life Impact Checklist | Cancer had a negative impact on sexual function reported by 40%, 58%, and 59% of 15-20y, 21-29y, and 30-39y, respectively. |

| Body Image | Life Impact Checklist | The majority (≥ 60%) of AYAs reported a negative impact on body image. | ||||

| Bober et al., 2013 | Cross-sectional | United States | Survivors of various cancers 18 to 57 years of age (mean 27 years) N=291 |

Sexual Function: Sexual Dysfunction Arousal, Desire, Orgasm, Enjoyment/pleasure, erection |

Swed-QUAL | 29% of participants classified as sexual dysfunction cases (reporting ≥2 problems). Associated factors included female sex, physical functioning, poor general and mental health and fatigue. |

| Carter et al., 2010 | Cross-sectional | United States | Female survivors of gynecological cancer or hematopoietic cell transplant 18 to 29 years of age N=172 |

Sexual Dysfunction Lubrication, Pain, Arousal, Desire, Satisfaction, Orgasm | FSFI | All FSFI score means for cancer survivors were in the range of sexual dysfunction (range 17.6-24.51). Cancer survivors experienced more pain and less lubrication than non-cancer infertile women. |

| Crawshaw, 2013 | Qualitative | United Kingdom | Male survivors of testicular cancer or lymphoma 21 to 40 years of age N=28 |

Sexuality, Relationship Factors | Semi-structured interviews | Masculinity can be impacted by treatment and infertility, which impacts men’s relationships and sexual activity. |

| Eeltink et al., 2013 | Cross-sectional | Netherlands | Female survivors of Hodgkin lymphoma 18 to 40 years of age N=144 (36 survivors and 108 controls) |

Sexual Dysfunction Lubrication, Pain, Arousal, Desire, | FSFI | 31% report sexual dysfunction. Female survivors >30 years of age who perceived themselves as infertile reported the lowest FSFI scores. |

| Ford et al., 2014 | Observational cohort – cross-sectional measure | United States Canada |

Female survivors of various cancers 18 to 51 years of age N=408 |

Sexual Dysfunction Lubrication, Pain, Arousal, Desire, Satisfaction |

SFQ-Female Women’s Health Questionnaire Sexual Self Schema |

Survivors reported poorer sexual functioning compared with siblings including decreased desire, arousal, and satisfaction. |

| Frederick, Recklitis, Blackmon, & Bober, 2016 | Qualitative | United States | Survivors of various cancers who reported ≥2 sexual functioning problems. 18 to 39 years of age N=22 |

Sexual Dysfunction | Semi-structured interviews | The most common sexual function problems were difficulty relaxing and enjoying sex. Five major themes emerged: interruption of psychosexual development, problems with sexual function, perception of body image, fertility concern, and inadequate clinical support. All participants reported inadequate clinical support regarding sexual health. |

| Geue, Schmidt, Sender, Sauter, & Friedrich, 2015 | Cross-sectional | Germany | Survivors of various cancers 15 to 30 years of age N=99 |

Quality of Romantic Relationships Sexuality Needs | Partnership Questionnaire Life Satisfaction Scale Supportive Care Needs Survey |

75% of survivors were satisfied with their romantic relationship. Women reported greater sexuality needs than men; physical function and duration of the relationship were associated with relationship and sexuality satisfaction. |

| Graugaard, Sperling, Hølge-Hazelton, Boisen, & Petersen, 2018 | Cross-sectional | Denmark | Survivors of various cancers 17 to 26 years of age N=822 |

Sexual Dysfunction Lubrication, Orgasm, Erection, Desire | Survey items assessed problems with orgasm, erection, vaginal dryness, and desire for sex | 22% of survivors reported a sexual problem within the past week. |

| Desire to Flirt, Quality of Romantic Relationships | Survey items assessed how cancer has impacted participant’s relationship and desire to flirt | Almost a quarter of participants reported cancer had a negative impact on desire to flirt and relationships. | ||||

| Body Image Feeling Attractive | Survey items assessing how cancer has impacted participant’s body image and attractiveness | About 50% reported cancer had a negative impact body image (53%) and feeling of attractiveness (45%). Females more likely to report a negative impact on body image compared with males. | ||||

| Haavisto, Henriksson, Heikkinen, Puukko-Viertomies, & Jahnukainen, 2016 | Cross-sectional | Finland | Male survivors of various cancers 25 to 38 years of age N=52 survivors, N=56 control participants |

Sexual Dysfunction Arousal, Satisfaction, Orgasm, Fantasy, Sexual Behaviors/Frequency |

Derogatis Interview for Sexual Functioning self-report | Survivors had poorer sexual functioning compared with the control group. Poorer sexual functioning was related to depressive symptoms, absence of a relationship. Findings suggest a decline of sexual function at an early age among survivors. |

| Jervaeus et al., 2016 | Qualitative | Sweden | Survivors of various cancers 16 to 24 years of age N=133 |

Childhood cancer survivors' views about sex and sexual experiences | Focus Group Discussions | In half of the focus group (N=20 groups), one or more participants in each group reported problems related to sexual life (e.g. scars that affected them in intimate situations, being tired, feeling unattractive or difficulties related to getting and maintaining an erection). |

| Survivors report concerns related to the physical body and an altered body that impacted their sexuality. | ||||||

| Lehmann et al., 2016 | Cross-sectional | United States | Survivors of non-central nervous system malignancies 20 to 40 years of age N=174 (87 survivors and 87 controls) |

Satisfaction | Global Measure of Sexual Satisfaction | Survivors and controls were similar in sexual satisfaction. Sexual satisfaction was related to relationship status satisfaction. |

| Relationship Status Relationship Status Satisfaction |

Scale of Body Connection Global Measure of Sexual Satisfaction Satisfaction with Relationship Status Scale |

Relationship status satisfaction was similar between survivors and general population controls; higher satisfaction was associated with being in a relationship (compared with being single), higher sexual satisfaction, a more positive body image, and lower body dissociation. | ||||

| Body Dissociation | Scale of Body Connection | Survivors did not differ from controls regarding body image or body dissociation. | ||||

| Lehmann, Keim, Ferrante, Olshefski, & Gerhardt, 2018 | Cross-sectional | United States | Survivors of various cancers 20 to 40 years of age N=90 |

Sexual Behavior/Frequency | Course of Life Questionnaire | Almost all survivors had reached each psychosexual milestone (≥90%), except for sexual debut (83.3%), and most participants felt they reached each milestone at the right time. |

| Lewis, Sheng, Rhodes, Jackson, & Schover, 2012 | Qualitative | United States | Survivors of breast cancer 25 to 45 years of age N=33 |

Psychosocial concerns | Semi-structured interviews | Cancer treatment had caused ≥ 1 sexual problem in a third of the participants (e.g., vaginal dryness, pain difficulty feeling excitement and pleasure, and difficulty reaching orgasm. |

| Löf, Winiarski, Giesecke, Ljungman, & Forinder, 2009 | Cross-sectional | Sweden | Survivors of hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HCT) 19 to 42 years of age N=73 |

Sexual Dysfunction | Swed-QUAL | HCT survivors reported worse sexual functioning compared with general population data (Swed-QUAL mean score for survivors 62.4 vs. general population 85.2, p <.001). |

| Body Image | Survey items assessed attractiveness | 49% of HCT survivors considered themselves attractive; 19% felt those around them considered them less attractive because of treatment/illness. | ||||

| Martelli et al., 2016 | Cross-sectional | France | Mal survivors of rhabdomyo-sarcoma 7-25 years of age N=18 |

Satisfaction Erection Ejaculation |

Questions derived from the International Workshop on Bladder-Prostate Rhabdomyosarcoma | Only three patients were sexually active who all reported satisfying sex and orgasms. |

| Moules et al., 2017 | Qualitative | Canada | Survivors of various cancers 19 to 26 years of age N=10 |

Survivors’ perspective on sexuality during and after adolescent cancer | Interviews | Survivors desire meaningful relationships and can feel behind in romantic experiences compared with peers. |

| Survivors reported changes in their body impacted their identity and self-esteem, which impacted their sexuality. | ||||||

| Nahata et al., 2020 | Qualitative | United States | Survivors of various cancers 23-42 years of age N=40 |

Relationship Factors | Interviews | Survivors reported a negative impact on romantic relationships and body image issues (feeling self-conscious) that negatively influence sexuality. |

| Body Image | ||||||

| Olsson et al., 2018 | Cross-sectional | Sweden | Survivors of various cancers 19 to 36 years of age N=540 (285 survivors, 255 controls) |

Satisfaction Desire Pain Lubrication (females) Erection (males) |

Study-specific instrument | Female cancer survivors report lower sexual satisfaction and less frequent orgasm compared with female controls. Male survivors reported lower sexual satisfaction and desire compared with male controls. |

| Ritenour et al., 2016 | Cross-sectional | United States Canada |

Male survivors of various cancers 20 to 50 years of age N=1622 (plus 271 siblings) |

Erectile Dysfunction Desire, Satisfaction, Orgasm |

International Index of Erectile Function | A larger proportion of survivors had erectile dysfunction according to the IIEF compared with siblings (12.3% vs 4.2%, respectively). Among survivors, older age, testicular radiation >10Gy, surgery involving spinal cord or sympathetic nerves or prostate or pelvis were associated with erectile dysfunction. |

| Robertson et al., 2016 | Mixed Methods | Australia | Survivors of various cancers 15 to 25 years of age 43 - Data are based on answers from these 16 participants who were in a relationship. |

Relationship Factors | Quantitative data - Psychosocial Adjustment to Illness Scale – Sexual Relationship Scale Qualitative data collected through interviews |

Half of survivors reported some relationship difficulty. AYAs identified emotional support with their partner as positive aspects of their relationships, and described relational conflict associated with communication difficulties and loss of sexual interest. |

| Rosenberg et al., 2017 | Mixed Methods | United States | Non-central nervous system malignancies 14 to 25 years of age N=35 |

Sexual Behaviors, Sexual Function, | Quantitative data derived from the Guidelines for Adolescent Preventative Services risk assessment. Qualitative data collected through semi-structured interviews |

Survivors reported that sexual relationships contributed to their identity. Males reported problems with sexual function while women reported missed opportunities for sexual experiences. |

| Relationship Factors | Participants describe romantic relationships are tied to their identity, and some report missing opportunities for intimacy. | |||||

| Body Image | Participants report insecurities about their body, which impact sexual desire. | |||||

| Stinson et al., 2015 | Qualitative | Canada | Survivors of various cancers 12 to 17 years of age N=20 |

Survivors Perspectives on Romantic and Sexual Relationships | Interviews | Romantic relationships were reported as an important source of support for adolescents during cancer therapy, but few opportunities for establishing these relationships in the context of cancer. |

| Sundberg, Lampic, Arvidson, Helström, & Wettergren, 2011 | Cross-sectional | Sweden | Survivors of various cancers 18 to 37 years of age N=224 |

Pain, Arousal, Desire, Satisfaction, Orgasm, Sexual Behavior/Frequency | Scale from ‘Sex in Sweden’ study | Sexual function between survivors and comparison group was similar. Male survivors more likely to feel unattractive and have low sexual interest compared with control group. Within survivor population, males with central nervous system tumors were more likely to report low sexual satisfaction. |

| Teall, Barrera, Barr, Silva, & Greenberg, 2013 | Cross-sectional | Canada | Survivors of lower extremity bone tumors 18 to 32 years of age N=28 |

Sexual dysfunction, Desire, Satisfaction, Orgasm, Enjoyment, Fantasy, Sexual Behavior/Frequency | Brief SFQ-M BISF-W |

There were no differences in sexual function by surgery type (i.e. limb salvage, amputation, rotationplasty). |

| Relationship Status Satisfaction | Brief SFQ-M BISF-W |

Among participants, satisfaction with relationship and current partner highly correlated with perceived social support. | ||||

| Thompson, Long, & Marsland, 2013 | Qualitative | United States | Female survivors of various cancers 18 to 25 years of age N=18 |

Emerging adult survivors' perceptions of their romantic relationships | Interviews | Survivors reported gaining emotional maturity but were cautious with disclosing their cancer history in the context of romantic relationships. Fertility concerns among survivors can also cause strain on relationships. |

| Survivors describe feeling self-conscious as a result of treatment-related physical changes which can have a negative impact on relationships. | ||||||

| Thompson, Marsland, Marshal, & Tersak, 2009 | Cross-sectional | United States | Survivors of various cancers 18 to 25 years of age N=120 (60 survivors and 60 controls) |

Relationship Status Relationship Satisfaction |

Relationship Assessment Scale Dating/Romantic Relationships Measure |

Compared with controls, survivors reported fewer romantic relationships and greater distress at relationship end. Within the survivor group, higher anxiety, older age at diagnosis, and more severe treatment intensity increased risk for relationship difficulties. |

| van Dijk et al., 2008 | Cross-sectional | Netherlands | Survivors of various tumors 16 to 40 years of age N=60 |

Satisfaction Fantasy |

Psychosexual and Social Functioning Questionnaire | Many survivors reported sexual problems (e.g. 41.4% no sexual attraction, 27.6% no intercourse, 44.8% not satisfied with sexual life). Prior sexual intercourse was less common among survivors compared with the Dutch general population (66.7% and 95%, respectively). Survivors treated during adolescence had a delay in sexual milestones compared with the survivors treated in childhood. |

| Feeling Attractive | Psychosexual and Social Functioning Questionnaire | 45% of participants seldom or never saw themselves as sexually attractive and 18% reported uncertainty about their body related to a limitation in their sexual life. | ||||

| Wettergren et al., 2017 | Cohort Study – longitudinal | United States | Survivors of various cancers 15 to 39 years of age N=465 |

Sexual Dysfunction | Life Impact Checklist | Cancer had negative impact on sexual function among 59% at one year after diagnosis and among 43% at two years after diagnosis. |

| Zebrack, Foley, Wittmann, & Leonard, 2010 | Cross-sectional | United States | Survivors of various cancers 18 to 39 years of age N=599 |

Sexual Dysfunction | MOS Sexual Functioning Scale | 42.7% endorsed at least one symptom (32% of male and 52% of female participants). Sexual function was correlated with distress and those with sexual dysfunction reported poorer health related quality of life. |

Prevalence of Sexual Dysfunction

Due to varied measurement, it was difficult to determine an overall proportion of cancer survivors with sexual dysfunction. In studies that used the Swed-Qual or Medical Outcome Study items, 42% to 52% of survivors reported ≥ 1 problem with sexual function19,23 while 29% of survivors reported ≥ 2 sexual function problems24. Compared with population norms, survivors reported worse sexual functioning overall.25 Using the FSFI, sexual dysfunction was reported by 31% of Hodgkin lymphoma survivors and 100% of survivors of gynecological cancer or hematopoietic cell transplant28. In a study of 822 survivors aged 17 to 26 years, 22% of survivors reported sexual dysfunction (e.g.,21problem with orgasm, erection, and/or vaginal dryness) within the past week.33 Using the International Index of Erectile Function in a study of 1,622 male survivors, 12% met criteria for erectile dysfunction.31 Across studies, female survivors reported more sexual dysfunction compared with males.33,23,36 Sexual dysfunction was identified as a substantial problem based upon qualitative data from cancer survivors.22,34,35,37

Other Aspects of Sexual Dysfunction

Additional concepts of sexual dysfunction were explored in these studies, and the majority suggest that compared to peers, cancer survivors report more problems with pain, lubrication, desire, and other sexual function factors, including overall sexual satisfaction.21,28,29,32,38,39 In a study of 540 AYA (15 to 29 years of age), male survivors reported lower sexual desire, females reported lower frequency of orgasm, and both males and females reported poorer sexual satisfaction, when compared with sex-matched peers.39 There are exceptions, as both Sundberg et al. (2011) and Lehmann et al. (2016) found sexual satisfaction to be similar between survivors and peers.40,41 The literature also supports that many survivors experience a delay in meeting sexual milestones (e.g., dating, first sexual intercourse) or are less likely to report frequent sexual activity when compared to peers.38,40,42

Similar to findings of overall sexual dysfunction, females report more problems with components of sexual function when compared with males.24,33,36 In a sample of 291 cancer survivors, a larger proportion of female survivors reported sexual problems (e.g. interest, enjoyment, arousal) compared with male survivors (37% vs 20%, p < 0.01)24. In qualitative studies, women in particular describe more pain, a lack of sexual desire, and difficultly enjoying sex; specific components reported by young men include erectile dysfunction, premature ejaculation, and problems with arousal.22,34

Relationship Factors

Five quantitative studies assessed relationship factors30,33,41,43,44, and relationships were a point of discussion among 7 qualitative or mixed methods studies20,37,43,44,45-47 (Table 1). Relationship status varied across studies, with studies of older survivors having a larger proportion of participants in a relationship. Among 822 Danish young adults diagnosed with cancer between 15 to 29 years of age, 69% were in a relationship at the time of survey completion.33 In the United States, 72.4% of survivors (20 to 40 years of age) were in a relationship or married, similar to the proportion of gender and age-matched controls.41 Among those aged 15 to 25 years, 37% reported being in a relationship during the first two years following treatment completion.37

In general, most partnered survivors report being satisfied with their relationship. In a sample of 99 young adults over the age of 18 years, 76% rated the quality of their relationship as high.44 Some survivors describe benefits to being in a relationship during and after treatment37,47; however, forming relationships can also be challenging particularly among younger AYAs who are isolated from peers and partners during cancer treatment.47 For example, in the Danish sample of AYAs diagnosed with cancer between 15 and 29 years of age and who were 1 to 7 years from diagnosis, almost 25% of the 822 participants responded that cancer negatively affected their relationship with their partner (22.0%) or their desire to flirt, date, or have a partner (23.6%).33 Uncertain fertility status or infertility can also negatively impact survivors’ romantic relationships, and some men describe infertility as threatening to their perceived masculinity and adding stress to their relationships.20,48

In addition, as AYAs express a desire for romantic and sexual relationships they also struggle with how and when to disclose their cancer history.45,48 Cancer has changed their perceived identity, and younger survivors often describe feeling more mature than peers, which can lead to some survivors having difficulty sharing emotions with romantic partners.48

Body Image

Seven quantitative studies included assessments of body image, feeling attractive, and feeling desirable25,26,33,36,38,40,41; these concepts were also addressed by participants in four qualitative studies35,45,46,48 (Table 1). Across studies, survivors reported issues with body image, feeling unattractive, and having uncertainty with their own body25,33,36,37,40,41,48,49, often attributed to the cancer experience. Among 523 survivors 15 to 39 years of age, the majority of respondents reported that cancer had a negative impact on their body image.26 Findings were similar in a sample of 822 Danish young adults, among whom 54% responded that cancer negatively affected their view of their own body.33 In qualitative interviews, survivors describe feeling self-conscious48 and worried about their ‘altered body’ and exposing their scars during intimate situations35. However, not all survivors report problems with body image; in a study of 87 long-term survivors, with an average age of 27 years and 16 years from their cancer diagnosis, survivors reported similar body image compared with controls.41 Assessment of body image varied and included scales focused on self-worth36 and appearance38 in addition to measures that were not validated33.

DISCUSSION

The findings from this review highlight the significant burden of impaired sexual function among AYAs after they complete cancer treatment. Nonetheless, and notably, this review demonstrates the complex relationships between sexual dysfunction, romantic relationships, and body image among AYA cancer survivors. As these domains have clearly been identified by patients and negatively impact quality of life, there is an imperative to (1) help providers identify problems early, and (2) test supportive interventions to address these challenges.

Survivors represented in this review varied in developmental stage from late adolescence through young adulthood, as well as in time since diagnosis, both factors that would be expected to influence sexual dysfunction. For example, whereas adolescent and early young adult50 survivors often experience interruption of psychosexual development and delay in sexual experiences compared with peers34,35, survivors in their late 20s or 30s are less likely to have those concerns but more likely to experience sexual dysfunction26,28. Moreover, this literature review also demonstrates that females are more likely to report sexual problems compared with males. Several studies offered explanations for poorer sexual functioning among females compared with males, suggesting that females experience psychological and emotional sequelae (depression, post-traumatic stress symptoms, feeling unattractive, communication problems with romantic partners) that could contribute to lower sexual desire and decreased satisfaction.23,39 Psychosocial implications of cancer treatment may be a driver among females, including poorer body image due to scarring.33 Additionally, female survivors are less likely than males to be asked about sexual health problems by their healthcare provider, which can result in unaddressed and untreated symptoms.51 Finally, females experience vaginal dryness and dyspareunia which likely contributes to sexual distress.21,22 It is important to note that certain cancers such as testicular germ cell tumors in men, are likely to have a particularly detrimental impact on sexual function and/or body image that is gender-specific.52

Previous reviews of sexual dysfunction among cancer survivors have focused on survivors of AYA cancer (cancer diagnosis between 15-39 years)6 and a clinically-focused narrative review of childhood cancer survivors.53 Here, we have conducted a more extensive and sharply focused review that includes AYA-aged survivors of both childhood and AYA cancer with the purpose of informing sexual health research across the spectrum of AYA cancer survivors. Additionally, through analysis of included studies we found that body image and romantic relationships emerged as important themes worthy of future academic pursuit, recognizing the intimate interplay between these factors.

Undoubtedly, body image, romantic relationships, and sexual function are related, and challenges in one area may affect another. For example, poor body image may impact survivors’ romantic relationships35, and sexual dysfunction, including lack of desire, may be influenced by body image, which in turn may lead to strain within romantic relationships. Similarly, during and after cancer treatment, survivors describe changes in self-image and identity that also impact sexuality and development of relationships.45,46 In addition, perceptions around infertility have potential to influence all three of these domains.20,28,48 While the studies that explored relationship factors and body image support an interplay of these elements with sexual function, there has not been any significant mediational analysis in the AYA survivorship literature to date that has examined these relationships.

The literature reflects a wide range of psychometric scales that offer varying definitions of sexual dysfunction, making it difficult to draw conclusions about the breadth and depth of sexual dysfunction in this population. Variability in research findings may reflect inconsistencies in measurement or other methodological issues. For example, the majority of AYA survivors who are in a relationship report that the quality of relationship satisfaction is high.44 However, relationship quality may be orthogonal to measures of sexual satisfaction or sexual function, which are not mutually exclusive.

Poor quality ratings for studies in this review were most often due to the study’s small sample size or sampling methodology, which limited the representativeness of the sample to the larger population of cancer survivors. For this reason, when exploring trends in sexual function in relation to cancer diagnoses or treatment exposures, we focused on publications that were rated fair or good quality. In several studies, sexual dysfunction was found to be associated with higher doses of testicular radiation, surgery involving spinal cord or pelvis31, and cancers of the breast, genital33, or central nervous system41. However, other studies found no relationship between cancer diagnosis, gonadotoxic treatment exposures, treatment intensity, or time from diagnosis.23,24,27, Given the heterogenous populations, variation in cancer diagnoses, and lack of clinical exposures documented in most studies, it is difficult to draw conclusions based on cancer diagnosis and treatment exposures.

Survivors consistently report a lack of sexual health discussions or guidance from healthcare providers and express a desire for providers to address these issues.34 The COG AYA Oncology Discipline Committee recognizes sexual health among AYAs as an unmet need and thus commissioned this review. Sexual health issues need increased attention in prospective trials aimed at AYAs, perhaps incorporating patient-reported outcomes of sexual health, testing education tools for providers, prospectively testing sexual dysfunction measurement tools in AYA, and increasing collaboration between adult and pediatric providers for knowledge translation. The cooperative research group setting may serve as an avenue for design and implementation of clinical trials of systematic assessment and interventions on a larger scale to improve sexual health among AYA during and after cancer. Research in this setting would also provide an avenue for examining sexual health problems in relation to specific cancer diagnoses and treatment exposures, which are critical gaps in the current literature. Spanning the age range of 15-39 years, AYAs represent a challenging population for cancer researchers because neither the pediatric nor the medical oncology disciplines are able to study or care for all patients. Thus, as is the case for therapeutic cancer clinical trials, sexual health research for AYAs with cancer may be best achieved through collaboration of the COG with adult-focused cooperative oncology groups that are also members of the National Cancer Institute’s National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN), including the SWOG Cancer Research Network, Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology, ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group, NRG Oncology, and the Canadian Cancer Trials Group.54 Leveraging the NCTN for sexual health research also offers the opportunity to reach AYAs in the community setting through the NCI Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP).54,55

Pediatric oncology clinicians who care for AYA cancer survivors describe a lack of experience discussing sexual health and recognize the need for further education regarding sexual health communication.56 Educational interventions for oncology providers have demonstrated improvement in provider-reported knowledge and practice, but the impact on patient-reported outcomes has not been routinely evaluated.57 The Enriching Communication Skills for Health Professionals in Oncofertility (ECHO) has demonstrated success in educating providers about sexual health among oncology patients.58 Sexual communication models, including PLISSIT59,60, can be helpful for providers to initiate sexual health discussions with patients. The incorporation of a sexual health clinic within the oncology setting has been successful with adult cancer patients61, and may serve as a model for AYA cancer survivors in some settings. AYA patients would also benefit from strong collaborations between oncology and survivorship providers with adolescent medicine, gynecology, and urology providers to address sexual problems. This review demonstrates a lack of tested interventions or strategies for addressing sexual dysfunction among AYA cancer survivors. Ultimately, interventions to improve sexual function should consider variability in psychosexual development, relationship status and the attainment of sexual milestones among AYAs. Thus, these findings strongly support the need for developmentally appropriate interventions and using approaches that account for biological and psychosocial factors to improve AYA cancer survivors’ sexual function.9 As the number of AYA survivors continue to grow, there is a pressing need for targeted information, education, and intervention around sexual health, intimate relationships and body image.

We acknowledge several limitations in this scoping review. First, we included only studies published in English in peer-reviewed journals. It is possible that studies of sexual function among AYA cancer survivors were published in other languages and are not represented in this review. Second, the focus of this review was survivors of cancer and the results do not represent sexual dysfunction experienced by AYA patients current on active cancer treatment. Most of the studies we included were rated as fair or poor in quality due to limited sample size, biased sampling designs, and unvalidated measurement tools. Finally, there is variation in the measurement across studies and the ability to make direct comparisons of sexual dysfunction between scales is limited. Future research is needed to identify appropriate tools to measure sexual function among AYA cancer survivors. The ASCO guidelines highlight the need for oncologists to ask their patients about sexual health concerns.9 Consequently, providers who see AYA cancer survivors must feel equipped to ask these questions and understand the potential breadth of sexual dysfunction, including significant factors such as body image and romantic relationships. Building on the results of this review, the COG is poised to develop a prospective study of AYA sexual health through inclusion of key measures within NCTN-wide survivorship studies, and concomitantly contribute to ongoing education for providers and patients.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

This work was supported by the Children’s Oncology Group under the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health award numbers U10CA180886 and U10CA098543, and the Children’s Oncology Group/Aflac Foundation. Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

References

- 1.Murphy D, Klosky JL, Reed DR, et al. : The importance of assessing priorities of reproductive health concerns among adolescent and young adult patients with cancer. Cancer 121:2529–36, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Metzger ML, Meacham LR, Patterson B, et al. : Female reproductive health after childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancers: guidelines for the assessment and management of female reproductive complications. J Clin Oncol 31:1239–47, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skinner R, Mulder RL, Kremer LC, et al. : Recommendations for gonadotoxicity surveillance in male childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer survivors: a report from the International Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Guideline Harmonization Group in collaboration with the PanCareSurFup Consortium. Lancet Oncol 18:e75–e90, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bober SL, Varela VS: Sexuality in adult cancer survivors: challenges and intervention. J Clin Oncol 30:3712–9, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zebrack B, Isaacson S: Psychosocial care of adolescent and young adult patients with cancer and survivors. J Clin Oncol 30:1221–6, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stanton AM, Handy AB, Meston CM: Sexual function in adolescents and young adults diagnosed with cancer: A systematic review. Journal of cancer survivorship : research and practice 12:47–63, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou ES, Frederick NN, Bober SL: Hormonal Changes and Sexual Dysfunction. Med Clin North Am 101:1135–1150, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carpentier MY, Fortenberry JD: Romantic and sexual relationships, body image, and fertility in adolescent and young adult testicular cancer survivors: a review of the literature. J Adolesc Health 47:115–25, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter J, Lacchetti C, Andersen BL, et al. : Interventions to Address Sexual Problems in People With Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Adaptation of Cancer Care Ontario Guideline. J Clin Oncol 36:492–511, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Children's Oncology Group: Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancers, Version 5.0. Monrovia, CA, Children's Oncology Group, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freyer DR, Felgenhauer J, Perentesis J: Children's Oncology Group's 2013 blueprint for research: adolescent and young adult oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer 60:1055–8, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, et al. : Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 18:143, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson RH: AYA in the USA. International Perspectives on AYAO, Part 5. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2:167–174, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Progress Review Group.: Closing the gap: research and care imperatives for adolescents and young adults with cancer (NIH Publication No. 06-6067). . Bethesda, MD, Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, and the LIVESTRONG Young Adult Alliance,, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bramer W, Bain P: Updating search strategies for systematic reviews using EndNote. Journal of the Medical Library Association : JMLA 105:285–289, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Covidence systematic review software. Melbourne, Australia, Veritas Health Innovation, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Institutes of Health: Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. , 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melnyk BF-O, E.: Evidence-based practice in nursing and healthcare, Wolters Kluwer Health, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Acquati C, Zebrack BJ, Faul AC, et al. : Sexual functioning among young adult cancer patients: A 2-year longitudinal study. Cancer 124:398–405, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crawshaw M: Male coping with cancer-fertility issues: putting the 'social' into biopsychosocial approaches. Reproductive biomedicine online 27:261–270, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carter J, Raviv L, Applegarth L, et al. : A cross-sectional study of the psychosexual impact of cancer-related infertility in women: third-party reproductive assistance. Journal of cancer survivorship : research and practice 4:236–246, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewis PE, Sheng M, Rhodes MM, et al. : Psychosocial concerns of young African American breast cancer survivors. Journal of psychosocial oncology 30:168–184, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zebrack BJ, Foley S, Wittmann D, et al. : Sexual functioning in young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psycho-oncology 19:814–822, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bober SL, Zhou ES, Chen B, et al. : Sexual function in childhood cancer survivors: a report from Project REACH. J Sex Med 10:2084–93, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Löf CM, Winiarski J, Giesecke A, et al. : Health-related quality of life in adult survivors after paediatric allo-SCT. Bone marrow transplantation 43:461–468, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bellizzi KM, Smith A, Schmidt S, et al. : Positive and negative psychosocial impact of being diagnosed with cancer as an adolescent or young adult. Cancer 118:5155–5162, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wettergren L, Kent EE, Mitchell SA, et al. : Cancer negatively impacts on sexual function in adolescents and young adults: The AYA HOPE study. Psycho-oncology 26:1632–1639, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eeltink CM, Incrocci L, Witte BI, et al. : Fertility and sexual function in female Hodgkin lymphoma survivors of reproductive age. Journal of clinical nursing 22:3513–3521, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haavisto A, Henriksson M, Heikkinen R, et al. : Sexual function in male long-term survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer 122:2268–2276, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teall T, Barrera M, Barr R, et al. : Psychological resilience in adolescent and young adult survivors of lower extremity bone tumors. Pediatric blood & cancer 60:1223–1230, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ritenour CWM, Seidel KD, Leisenring W, et al. : Erectile Dysfunction in Male Survivors of Childhood Cancer-A Report From the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. The journal of sexual medicine 13:945–954, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ford JS, Kawashima T, Whitton J, et al. : Psychosexual functioning among adult female survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol 32:3126–36, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Graugaard C, Sperling CD, Hølge-Hazelton B, et al. : Sexual and romantic challenges among young Danes diagnosed with cancer: Results from a cross-sectional nationwide questionnaire study. Psycho-oncology 27:1608–1614, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frederick NN, Recklitis CJ, Blackmon JE, et al. : Sexual Dysfunction in Young Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer 63:1622–8, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jervaeus A, Nilsson J, Eriksson LE, et al. : Exploring childhood cancer survivors' views about sex and sexual experiences -findings from online focus group discussions. European journal of oncology nursing : the official journal of European Oncology Nursing Society 20:165–172, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barrera M, Teall T, Barr R, et al. : Sexual function in adolescent and young adult survivors of lower extremity bone tumors. Pediatric blood & cancer 55:1370–1376, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robertson EG, Sansom-Daly UM, Wakefield CE, et al. : Sexual and Romantic Relationships: Experiences of Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Survivors. Journal of adolescent and young adult oncology 5:286–291, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Dijk EM, van Dulmen-den Broeder E, Kaspers GJ, et al. : Psychosexual functioning of childhood cancer survivors. Psychooncology 17:506–11, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olsson M, Steineck G, Enskär K, et al. : Sexual function in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors-a population-based study. J Cancer Surviv 12:450–459, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sundberg KK, Lampic C, Arvidson J, et al. : Sexual function and experience among long-term survivors of childhood cancer. Eur J Cancer 47:397–403, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lehmann V, Hagedoorn M, Gerhardt CA, et al. : Body issues, sexual satisfaction, and relationship status satisfaction in long-term childhood cancer survivors and healthy controls. Psycho-oncology 25:210–216, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lehmann V, Keim MC, Ferrante AC, et al. : Psychosexual development and satisfaction with timing of developmental milestones among adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psycho-oncology 27:1944–1949, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thompson AL, Marsland AL, Marshal MP, et al. : Romantic relationships of emerging adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psycho-oncology 18:767–774, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Geue K, Schmidt R, Sender A, et al. : Sexuality and romantic relationships in young adult cancer survivors: satisfaction and supportive care needs. Psycho-oncology 24:1368–1376, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moules NJ, Estefan A, Laing CM, et al. : "A Tribe Apart": Sexuality and Cancer in Adolescence. Journal of pediatric oncology nursing : official journal of the Association of Pediatric Oncology Nurses 34:295–308, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosenberg AR, Bona K, Ketterl T, et al. : Intimacy, Substance Use, and Communication Needs During Cancer Therapy: A Report From the "Resilience in Adolescents and Young Adults" Study. The Journal of adolescent health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine 60:93–99, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stinson JN, Jibb LA, Greenberg M, et al. : A Qualitative Study of the Impact of Cancer on Romantic Relationships, Sexual Relationships, and Fertility: Perspectives of Canadian Adolescents and Parents During and After Treatment. Journal of adolescent and young adult oncology 4:84–90, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thompson AL, Long KA, Marsland AL: Impact of childhood cancer on emerging adult survivors' romantic relationships: a qualitative account. J Sex Med 10 Suppl 1:65–73, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nahata L, Morgan TL, Lipak KG, et al. : Romantic Relationships and Physical Intimacy Among Survivors of Childhood Cancer. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 9:359–366, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arnett JJ: Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol 55:469–80, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reese JB, Sorice K, Beach MC, et al. : Patient-provider communication about sexual concerns in cancer: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv 11:175–188, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jonker-Pool G, Van de Wiel HBM, Hoekstra HJ, et al. : Sexual Functioning After Treatment for Testicular Cancer—Review and Meta-Analysis of 36 Empirical Studies Between 1975–2000. Archives of Sexual Behavior 30:55–74, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sopfe J, Gupta A, Appiah LC, et al. : Sexual Dysfunction in Adolescent and Young Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer: Presentation, Risk Factors, and Evaluation of an Underdiagnosed Late Effect: A Narrative Review. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weiss AR, Nichols CR, Freyer DR: Enhancing Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Research Within the National Clinical Trials Network: Rationale, Progress, and Emerging Strategies. Semin Oncol 42:740–7, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McCaskill-Stevens W, Lyss AP, Good M, et al. : The NCI Community Oncology Research Program: what every clinician needs to know. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Frederick NN, Campbell K, Kenney LB, et al. : Barriers and facilitators to sexual and reproductive health communication between pediatric oncology clinicians and adolescent and young adult patients: The clinician perspective. Pediatr Blood Cancer 65:e27087, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Albers LF, Palacios LAG, Pelger RCM, et al. : Can the provision of sexual healthcare for oncology patients be improved? A literature review of educational interventions for healthcare professionals. J Cancer Surviv, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Quinn GP, Bowman Curci M, Reich RR, et al. : Impact of a web-based reproductive health training program: ENRICH (Educating Nurses about Reproductive Issues in Cancer Healthcare). Psychooncology 28:1096–1101, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Perz J, Ussher JM, Australian C, et al. : A randomized trial of a minimal intervention for sexual concerns after cancer: a comparison of self-help and professionally delivered modalities. BMC cancer 15:629–629, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bober SL, Reese JB, Barbera L, et al. : How to ask and what to do: a guide for clinical inquiry and intervention regarding female sexual health after cancer. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 10:44–54, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Duimering A, Walker LM, Turner J, et al. : Quality improvement in sexual health care for oncology patients: a Canadian multidisciplinary clinic experience. Support Care Cancer 28:2195–2203, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martelli H, Borrego P, Guerin F, et al. Quality of life and functional outcome of male patients with bladder-prostate rhabdomyosarcoma treated with conservative surgery and brachytherapy during childhood. Brachytherapy. 2016;15:306–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.