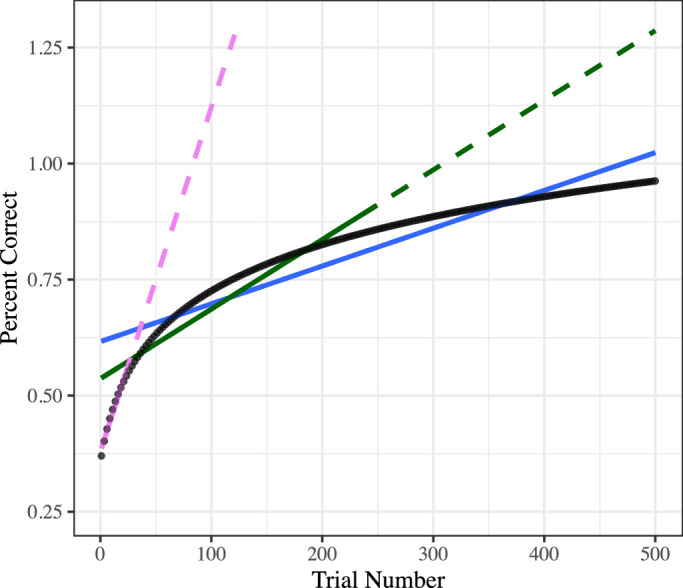

Figure 1.

Implications of the timescale-dependent biases of linear fits. While a linear relationship is clearly biologically implausible in the limit, even in smaller time windows, an inappropriate assumption of linearity can create problems. In the example above, a given “true” learning curve (black dotted line) is plotted alongside solid lines of linear fits to 50 trials (purple), 250 trials (green), or 500 trials (blue). Critically, despite each being fit to the same actual learning process, the various linear models provide very different inferences regarding the nature of learning. The 50-trial linear fit necessarily indicates rapid learning that, if extrapolated from (dotted line continuation), quickly reaches impossibly large values of accuracy. The 500-trial linear model meanwhile necessarily fits a flatter line (i.e., putatively “slower” change) than the models fit to a smaller number of trials. The 500-trial model thereby misses, by design, the early rapid changes of the learning curve. The slopes, beginning levels, and ending levels of performance diverge between all models. All models extrapolate to impossible levels of accuracy (i.e., over 100%).