Graphical abstract

Keywords: Critical illness, Children, Medical devices, Plasticizers, DEHP, Attention

Abbreviations: 5cx-MEPP, mono-(2-ethyl-5-carboxypentyl) phthalate; 5OH-MEHP, mono-(2-ethyl-5-hydroxyhexyl) phthalate; 5oxo-MEHP, mono-(2-ethyl-5-oxohexyl) phthalate; ATBC, tributyl-O-acetyl citrate; DEHA, bis(2-ethylhexyl) adipate; DEHP, di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate; DEHTP, bis(2-ethylhexyl) terephthalate; DINCH, di-isononyl-cyclohexane-1,2-dicarboxylate; DiDP, di-isodecyl phthalate; DiNP, di-isononyl phthalate; DPHP, di-propylheptyl phthalate; ICU, intensive care unit; MEHP, mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate; PEPaNIC trial, the Early versus Late Parenteral Nutrition in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PEPaNIC) trial; PICU, pediatric intensive care unit; PN, parenteral nutrition; TGC, tight glucose control; UPLC-MS/MS, ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry; TOTM, tris(2-ethylhexyl) trimellitate

Highlights

-

•

Exposure of critically ill children to DEHP in the PICU decreased over the years.

-

•

Reduced DEHP exposure in the PICU did not result in improved long-term attention.

-

•

Whether alternative plasticizers are neurodevelopmentally safe remains unclear.

Abstract

Background

Children who have been critically ill face long-term developmental impairments. Iatrogenic exposure to di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP), a plasticizer leaching from plastic indwelling medical devices used in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU), has been associated with the pronounced attention deficit observed in children 4 years after critical illness. As concerns about DEHP toxicity increased, governmental authorities urged the phase out of DEHP in indwelling medical devices and replacement with alternative plasticizers. We hypothesized that exposure to DEHP decreased over the years, attenuating the pronounced long-term attention deficit of these vulnerable children.

Methods

We compared plasma concentrations of 3 oxidative DEHP metabolites (5cx-MEPP, 5OH-MEHP, 5oxo-MEHP) on the last PICU day in 216 patients who participated in the Tight Glucose Control study (2004–2007) and 334 patients who participated in the PEPaNIC study (2012–2015) and survived PICU stay. Corresponding minimal exposures to these metabolites (plasma concentration multiplied with number of days in PICU) were also evaluated. In patients with 4-year follow-up data, we compared measures of attention (standardized reaction times and consistency). Comparisons were performed with univariable analyses and multivariable linear regression analyses adjusted for baseline risk factors.

Results

In the PEPaNIC patients, last PICU day plasma concentrations of 5cx-MEPP, 5OH-MEHP, 5oxo-MEHP and their sum, and corresponding minimal exposures, were reduced to 17–69% of those in the Tight Glucose Control study (p < 0.0001). Differences remained significant after multivariable adjustment (p ≤ 0.001). PEPaNIC patients did not show better attention than patients in the Tight Glucose Control study, also not after multivariable adjustment for risk factors.

Conclusion

Exposure of critically ill children to DEHP in the PICU decreased over the years, but the lower exposure did not translate into improved attention 4 years later. Whether the residual exposure may still be toxic or whether the plasticizers replacing DEHP may not be safe for neurodevelopment needs further investigation.

1. Introduction

Critically ill children are admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) for medical conditions that acutely require vital organ support to avoid imminent death. Although most children, fortunately, recover well from the acute insult, many children are confronted with important long-term problems years after hospital discharge, including impaired neurocognitive development, growth retardation, poor physical functioning, and consequently reduced quality of life (Banwell et al., 2003, Mammen et al., 2012, Mesotten et al., 2012, Viner et al., 2012, Garcia Guerra et al., 2013, Manning et al., 2018, Verstraete et al., 2018, Verstraete et al., 2019, Hordijk et al., 2020, Jacobs et al., 2020).

The pathophysiology of the adverse legacy after critical illness remains largely unexplained. However, several avoidable factors related to intensive care management have been shown to induce or aggravate aspects of the long-term developmental impairments of the children. Such factors include the typical stress-induced hyperglycemia as shown in the Tight Glucose Control study (Mesotten et al., 2012) and the early use of parenteral nutrition as shown in the PEPaNIC study (Verstraete et al., 2019, Jacobs et al., 2020). Another modifiable factor relates to the heavy reliance of intensive care on the use of plastic indwelling medical devices to provide the essential vital organ support. These devices are made softer and more flexible via the incorporation of chemical softeners or plasticizers. Historically, di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) has been used for this purpose, but was shown to leach from the devices during use as it is not chemically bound to the plastic polymer (Gayathri et al., 2004, Bagel et al., 2011, Ciellini et al., 2011, Kastner et al., 2012, Gimeno et al., 2014). As such, neonatal, pediatric and adult ICU patients have been shown to be massively exposed to DEHP leaching from the indwelling devices, with extremely high levels of DEHP metabolites found in patient’s urine and blood (Green et al., 2005, Weuve et al., 2006, Huygh et al., 2015, Verstraete et al., 2016). Concerns had already been raised about toxicity of exposure to DEHP for fertility, (neurocognitive) development and carcinogenicity, among others (Tanaka, 2002, Engel et al., 2010, Whyatt et al., 2012, Polanska et al., 2014, Gore et al., 2015, Zarean et al., 2016). Within the intensive care setting, we have identified a threshold of exposure to circulating DEHP metabolites as potentially harmful for neurocognitive development of children admitted to the PICU during the Tight Glucose Control study (Verstraete et al., 2016). Exceeding this threshold was independently and robustly associated with the pronounced attention problem of the children, explaining half of this deficit. Remarkably, all contemporary indwelling devices and/or the essential accessories for using them were shown to leach DEHP ex vivo (Verstraete et al., 2016).

The increasing concerns about DEHP toxicity urged the phase-out of DEHP from plastic indwelling medical devices and replacement with alternative plasticizers, as endorsed by several governmental authorities and societies (FDA, 2001, Directive, 2007, SCENIHR, 2015, Gore et al., 2015). In a recent study, in which we investigated all components and accessories of plastic indwelling medical devices contemporarily used in two PICUs during the PEPaNIC study (Fivez et al., 2016), we observed that the phasing out of DEHP had started (Malarvannan et al., 2019). Although DEHP was still present in 62% of the tested components, various alternative plasticizers were detected, and in only less than 30% of the components, DEHP was the predominant plasticizer.

In the present study, we addressed the hypothesis that, in view of the phasing out of DEHP, exposure of critically ill children to DEHP metabolites in the PEPaNIC study (2012–2015) (Fivez et al., 2016) would be markedly lower than that during the earlier performed Tight Glucose Control trial (2004–2007) (Mesotten et al., 2012, Verstraete et al., 2016). Consequently, if the alternative plasticizers used to replace DEHP would be safer and not adversely affect attention, we would expect that the attention deficit would be less pronounced in the PEPaNIC patients.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design and participants

This study was a preplanned secondary analysis of the PEPaNIC study on short- and long-term impact of timing of supplemental parenteral nutrition (PN) in the PICU (Fivez et al., 2016, Verstraete et al., 2019: Jacobs et al., 2020), which made use of a comparison with data obtained in an older study on short- and long-term impact of Tight Glucose Control with insulin in the PICU (Vlasselaers et al., 2009, Mesotten et al., 2012, Verstraete et al., 2016).

The Tight Glucose Control study randomly allocated 700 children up to 16 years old, admitted to the Leuven PICU between October 2004 and December 2007, to contemporary conventional glucose control tolerating hyperglycemia (CGC group) or tight glucose control to age-adjusted normoglycemia (TGC group) (Vlasselaers et al., 2009). The multicenter PEPaNIC study randomly allocated 1440 critically ill children up to 17 years old, admitted to the PICUs of Leuven, Rotterdam and Edmonton between June 2012 and July 2015, to receive early (early-PN group) or delayed (late-PN group) initiation of supplemental PN when 80% of targeted calories per age and weight categories was not reached (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01536275) (Fivez et al., 2016). Details on the glucose management for both study arms in the Tight Glucose Control study and the nutritional management for both study arms in the PEPaNIC study are given in the Appendix Methods A.1, together with the inclusion and exclusion criteria for participation in those studies.

In view of the observational design of the present study, comparing patients admitted to the PICU participating in two studies that had been performed 8 years apart, we needed to exclude as much as possible potential confounding by changes in patient management. As the Tight Glucose Control study showed improved outcome with TGC as compared with CGC (Vlasselaers et al., 2009), TGC became routine management in the Leuven PICU and hence was applied to all PEPaNIC patients included in Leuven. However, the other centers participating in the PEPaNIC study applied a less strict glucose control. Thus, to avoid confounding by differences in glucose control, only the TGC group of the Tight Glucose Control study and the Leuven patients included in the PEPaNIC study remained eligible for the present study. Standard nutritional management during the Tight Glucose Control study was the same as that applied to the patients randomized to early-PN in the PEPaNIC study, consisting of early full feeding, whereas the nutritional management in the late-PN group accepted an early macronutrient deficit. Hence, for the present study, we only selected patients from the TGC group in the Tight Glucose Control study and patients from the early-PN group included in Leuven during the PEPaNIC study, as these patients received exactly the same glucose and nutritional management during PICU stay (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of study participants. 4yFU: 4-year follow-up, CGC: conventional glucose control, DEHP: di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate, PICU: pediatric intensive care unit, PN: parenteral nutrition, TGC: tight glucose control.

Patients who participated in the Tight Glucose Control and PEPaNIC studies had been invited for a broad, in-depth assessment of long-term physical and neurocognitive development 4 years after PICU admission, each time in comparison with matched healthy controls (Mesotten et al., 2012, Jacobs et al., 2020). Validated internationally recognized questionnaires and clinical tests with adequate normative data were used to assess parent-reported emotional and behavioral problems and executive functions, intelligence, visual-motor integration, memory, motor coordination, and of particular importance for the present study also attention/alertness (Appendix Methods A.2). The latter was evaluated via computerized tasks of the “Baseline Speed” component of the Amsterdam Neuropsychological Task Battery, measuring simple reaction times to 32 visual stimuli, with mean reaction times and standard deviation (“consistency”) of reaction times calculated for the right and left hand separately (De Sonneville, 2014). Reaction times in milliseconds were converted to Z-scores. Assessments had been performed by physicians and experienced pediatric psychologists who had not been involved in the care of the patients during their stay in the PICU and who were strictly masked for treatment allocation.

Parents or legal guardians, and when applicable participants themselves (when 18 years or older), gave written informed consent for participation in the studies and/or corresponding follow-up. The institutional review boards approved the studies (ML2586, ML8052; NL49708.078; Pro00038098), which were performed in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments.

2.2. Quantification of DEHP metabolites in plasma

During the Tight Glucose Control and PEPaNIC studies, blood samples had been collected upon PICU admission and daily at 06.00 a.m. until PICU discharge (Vlasselaers et al., 2009, Fivez et al., 2016). After centrifugation, plasma was stored at −80 °C. Leaching experiments excluded any contamination with DEHP from the containers used to collect and store the plasma (Verstraete et al., 2016). Information on the indwelling plastic medical devices used for intensive care treatments during both studies is given in Appendix Tables A.1 and A.2.

In the Tight Glucose Control study, concentrations of four DEHP metabolites have been quantified in plasma samples available at the last day in PICU from those patients for whom intelligence had been assessed 4 years after PICU admission (Verstraete et al., 2016) (n = 216, Fig. 1). This was done by ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS). The metabolites comprised mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (MEHP) and its oxidative metabolites mono-(2-ethyl-5-carboxypentyl) phthalate (5cx-MEPP), mono-(2-ethyl-5-hydroxyhexyl) phthalate (5OH-MEHP) and mono-(2-ethyl-5-oxohexyl) phthalate (5oxo-MEHP).

The same, slightly modified, procedure was now used to quantify these metabolites in all plasma samples collected at the last day in PICU during the PEPaNIC study. More specifically, the procedure started with the addition of 200 µL of plasma to clean glass tubes, spiked with 50 µL of an internal standard mixture (containing 25 ng of each 13C-labeled DEHP metabolite, Cambridge Isotope Laboratories Inc., Andover, MA). To ensure deconjugation of targeted metabolites, 25 μL of β-glucuronidase (from E. coli powder (Supelco), 2 mg/mL in phosphate buffer) and 1 mL of phosphate buffer solution (pH 6) were added to the sample and the mixture was kept at 37 °C for 90 min. Analytes were extracted using Oasis MAX (30 mg, 3 mL, Waters, Milford, MA, USA). The sorbent was washed with 3 mL MilliQ water containing 5% NH4OH followed by 1 mL MilliQ water and then dried under vacuum. Elution was performed using 6 mL of methanol containing 2% formic acid. The eluate was finally evaporated to near dryness and reconstituted in 100 μL of acetonitrile: MilliQ water (1:1). The reconstituted extract was filtered through centrifugal filters of 0.45 µm pore size (VWR International, Leuven, Belgium). Instrumental analysis of plasma extracts was carried out on an Agilent 1290 series liquid chromatography system coupled to an Agilent 6460 Triple Quadrupole mass spectrometer (UPLC-MS/MS, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source. Detailed instrumental conditions for the analysis of DEHP metabolites are described in Verstraete et al. (2016). All solvents were of gradient grade for liquid chromatography (Merck). Formic acid (98–100%) was bought from Merck and NH4OH (aqueous solution of 28–30%) from Sigma-Aldrich (Bornem, Belgium). All glassware was soaked for 12 h in an alkali solution (diluted RBS T 105, pH 11–12) and, after washing, glassware was rinsed with water and dried overnight at 400 °C. Prior to use, glassware was rinsed with acetonitrile. Details on the participation to international interlaboratory exercises for quantification of urinary DEHP metabolite concentrations before or during the period of the analyses related to this manuscript are shown in Appendix Table A.3.

The sum of the molar concentrations of 5cx-MEPP, 5OH-MEHP, and 5oxo-MEHP was calculated as total oxidative DEHP metabolites. Both concentration to which the brain is directly or indirectly exposed and the duration of such exposure would determine any eventual long-term neurocognitive harm (Chen et al., 2011, You et al., 2018, Ahmadpour et al., 2021). As in our previous study (Verstraete et al., 2016), we therefore also investigated the exposure to 5cx-MEPP, 5OH-MEHP, and 5oxo-MEHP and total oxidative DEHP metabolite exposure that was minimally present (“minimal exposure”) for each patient during PICU stay, which was calculated as the product of the last day plasma concentration and the duration of PICU stay. We worked with the last day plasma concentrations and “minimal exposure” as that previous study (Verstraete et al., 2016) showed that this was most discriminative, with robust associations with neurocognitive outcome found for the minimal exposure, but not for the brief, very high admission peak of DEHP metabolite concentrations or area under the curve.

2.3. Statistical analyses

Univariable comparisons were performed with Chi-square (Fisher exact) or Mann-Whitney U tests, as appropriate. Data are presented as numbers with proportions or medians with interquartile ranges.

For the comparison of DEHP metabolite concentrations and minimal exposure to these metabolites during the Tight Glucose Control and PEPaNIC studies, we selected all patients from the TGC and early-PN groups who participated in the respective studies, who survived PICU stay, and for whom we quantified the last PICU day DEHP metabolite concentrations (cohort 1). To compare the attention function in both studies, we selected all patients from cohort 1 who also had attention measures available as Z-scores (cohort 2).

After univariable analyses, multivariable linear regression analyses (standard least squares) were performed adjusted for risk factors that may affect the respective outcomes, based on clinical practice and literature. For the DEHP metabolite analyses, these risk factors included age at PICU admission, sex, height (Z-score), weight (Z-score), history of malignancy, history of diabetes, and type (cardiac surgery, other surgery, or medical reason) and severity (Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction (PeLOD) score of the first 24 h) of critical illness, with additional adjustment for duration of PICU stay for minimal metabolite exposures as outcome. Analyses for attention were adjusted for age at PICU admission, sex, race, geographic and linguistic origin, history of malignancy, history of diabetes, educational and occupational level of the parents (Appendix Methods A.3), and type (cardiac surgery, other surgery or medical reason) and severity (PeLOD score of the first 24 h) of critical illness. As different pediatric psychologists evaluated attention of the children in both studies, we also compared attention in propensity score-matched subgroups of the healthy controls included in both studies (Mesotten et al., 2012, Jacobs et al., 2020) and of patients and controls in the respective studies, to avoid confounding by tester variability (Appendix Methods A.4). Propensity score matching was performed with the “MatchIt” package in R4.0.3 with age and sex as covariates, and based on one-to-one nearest neighbor matching without replacement.

Statistical analyses were performed with JMP Pro 15.1.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). P-values lower than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Exposure to DEHP metabolites in the PEPaNIC as compared with the Tight Glucose Control study

Since in the Tight Glucose Control study DEHP metabolite concentrations were only measured in PICU survivors, PICU non-survivors of the PEPaNIC study were also excluded for the comparison of the metabolites and corresponding minimal exposure among both studies. This yielded 334 patients in the PEPaNIC study to compare with 216 patients in the Tight Glucose Control study as “Cohort 1” (Fig. 1). Patients in both study groups were comparable for sex, age at PICU admission, history of malignancy or diabetes, and length of PICU stay (Table 1). However, patients in the PEPaNIC study were overall somewhat smaller and weighed less, were less frequently admitted after cardiac surgery and more after non-cardiac surgery, and had a higher severity of illness, as compared with those in the Tight Glucose Control study.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Cohort 1 with DEHP metabolites |

Cohort 2 with DEHP metabolites and attention |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | TGC study (n = 216) | PEPaNIC study (n = 334) | p-value | TGC study (n = 208) | PEPaNIC study (n = 171) | p-value |

| Sex | 0.88 | 0.69 | ||||

| Male, n (%) | 121 (56.0) | 185 (55.4) | 115 (55.3) | 98 (57.3) | ||

| Female, n (%) | 95 (44.0) | 153 (44.1) | 93 (44.7) | 73 (42.7) | ||

| Age at PICU admission (years), median (IQR) | 1.5 (0.3–5.7) | 1.9 (0.4–6.0) | 0.19 | 1.5 (0.3–6.0) | 1.8 (0.4–4.6) | 0.95 |

| Age at 4-year follow-up (years), median (IQR) | 5.4 (4.2–9.8) | 5.6 (4.5–8.4) | 0.10 | |||

| Height at PICU admission (Z-score), median (IQR) | −0.2 (−1.1 to 0.6) | −0.4 (−1.7 to 0.5) | 0.02 | −0.2 (−1.1 to 0.6) | −0.0 (−1.0 to 0.8) | 0.44 |

| Weight at PICU admission (Z-score), median (IQR) | −0.4 (−1.1 to 0.5) | −0.6 (−1.6 to 0.3) | 0.007 | −0.4 (−1.1 to 0.6) | −0.4 (−1.2 to 0.5) | 0.78 |

| Known non-Caucasian race, n (%) a | 21 (10.1) | 8 (4.7) | 0.04 | |||

| Known not exclusively European origin, n (%) a | 30 (14.4) | 31 (18.1) | 0.32 | |||

| Known not exclusively Dutch (or English) language, n (%) | 49 (23.6) | 43 (25.2) | 0.71 | |||

| Socioeconomic status | ||||||

| Parental educational level b | <0.0001 | |||||

| Educational level 1 | 34 (16.4) | 21 (12.3) | ||||

| Educational level 2 | 102 (49.0) | 65 (38.0) | ||||

| Educational level 3 | 63 (30.3) | 55 (32.2) | ||||

| Educational level unknown | 9 (4.3) | 30 (17.5) | ||||

| Parental occupational level c | <0.0001 | |||||

| Occupational level 1 | 46 (22.1) | 15 (8.8) | ||||

| Occupational level 2 | 93 (44.7) | 53 (31.0) | ||||

| Occupational level 3 | 45 (21.6) | 46 (26.9) | ||||

| Occupational level 4 | 15 (7.2) | 29 (17.0) | ||||

| Occupational level unknown | 9 (4.3) | 28 (16.4) | ||||

| History of malignancy, n (%) | 8 (3.7) | 20 (6.0) | 0.22 | 8 (3.9) | 11 (6.4) | 0.25 |

| History of diabetes, n (%) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) | 0.75 | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.27 |

| Admission diagnosis | <0.0001 | 0.002 | ||||

| Cardiac surgery, n (%) | 167 (77.3) | 201 (60.2) | 161 (77.4) | 107 (62.6) | ||

| Other surgery, n (%) | 24 (11.1) | 85 (25.5) | 23 (11.1) | 40 (23.4) | ||

| Medical reason, n (%) | 25 (11.6) | 48 (14.4) | 24 (11.5) | 24 (14.0) | ||

| PeLOD score first 24 h, median (IQR) d | 22 (11–32) | 31 (21–32) | <0.0001 | 22 (11–32) | 31 (21–32) | 0.0009 |

| PICU length of stay, median (IQR) | 2 (2–5) | 3 (1–6) | 0.70 | 2 (2–5) | 3 (2–6) | 0.61 |

DEHP: di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate, IQR: interquartile range, PeLOD: Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction score, PICU: pediatric intensive care unit, TGC: Tight Glucose Control.

Participants were classified according to race and geographical origin by the investigators, in order to capture ethnical and regional differences in the frequency of consanguinity, which may adversely affect cognitive performance.

The educational level is the average of the paternal and maternal educational levels, which were calculated based upon the 3-point scale subdivisions as made by the Algemene Directie Statistiek (Belgium; statbel.fgov.be/nl/) and the Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek (The Netherlands; statline.cbs.nl): Low (=1), middle (=2) and high (=3) educational level (Appendix Methods A.3).

The occupational level is the average of the paternal and maternal occupational levels, which were calculated based upon the International Isco System 4-point scale for professions (Appendix Methods A.3).

Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction (PeLOD) scores range from 0 to 71, with higher scores indicating more severe illness.

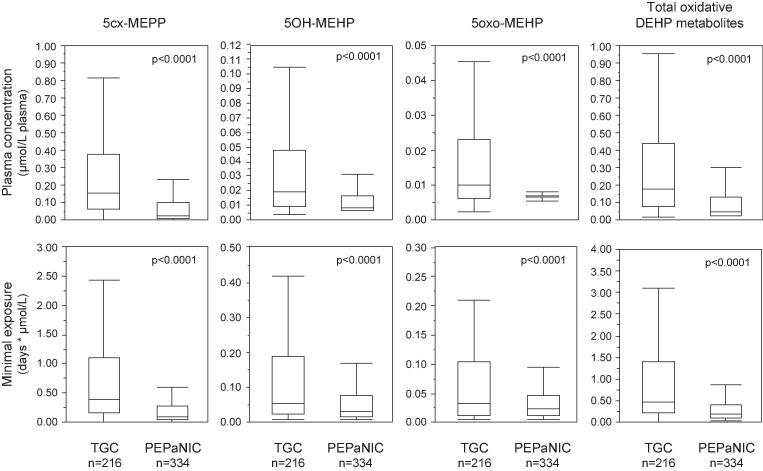

In univariable analyses, plasma concentrations on the last PICU day of 5cx-MEPP, 5OH-MEHP, 5oxo-MEHP and the sum of these metabolites were significantly lower in PEPaNIC patients as compared with those in the Tight Glucose Control study, with median reductions to 17–66% residual levels (Fig. 2). The corresponding minimal exposures to these metabolites were reduced to 23–69% of the exposures in the Tight Glucose Control study. After multivariable adjustment, all last PICU day plasma concentrations and minimal exposures remained significantly lower during the PEPaNIC study as compared with during the Tight Glucose Control study (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of plasma concentrations of oxidative DEHP metabolites and corresponding minimal exposure in the Tight Glucose Control and PEPaNIC studies. Plasma concentrations and minimal exposure to the oxidative DEHP metabolites were compared for all surviving patients for whom these metabolites were measured in the TGC group of the Tight Glucose Control study and in the Early-PN group of the PEPaNIC study (Cohort 1, see Fig. 1). Total oxidative DEHP metabolites were calculated as the sum of the molar concentrations of 5cx-MEPP, 5OH-MEHP and 5oxo-MEHP. Minimal exposure to the metabolites was calculated as the product of the last day plasma concentration and the duration of PICU stay. Boxes represent medians and interquartile ranges, and whiskers are drawn to the furthest point within 1.5 × IQR from the box. 5cx-MEPP: mono-(2-ethyl-5-carboxypentyl) phthalate, 5OH-MEHP: mono-(2-ethyl-5-hydroxyhexyl) phthalate, 5oxo-MEHP: mono-(2-ethyl-5-oxohexyl) phthalate, IQR: interquartile range, PN: parenteral nutrition, TGC: tight glucose control.

Table 2.

Multivariable analyses for oxidative DEHP metabolite plasma concentrations and minimal exposure during the PEPaNIC study as compared with those during the Tight Glucose Control study.

| Cohort 1 a |

Cohort 2 b |

Cohort 2 b further adjusted |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolites | Scaled estimate (95 %CI) c, d | P | Scaled estimate (95 %CI) c, d | P | Scaled estimate (95 %CI) c, e | P |

| Last day concentrations | ||||||

| 5cx-MEPP | −0.091 (−0.113 ; −0.068) | <0.0001 | −0.095 (−0.124 ; −0.065) | <0.0001 | −0.096 (−0.128 ; −0.064) | <0.0001 |

| 5OH-MEHP | −0.013 (−0.019 ; −0.007) | <0.0001 | −0.015 (−0.020 ; −0.011) | <0.0001 | −0.016 (−0.021 ; −0.011) | <0.0001 |

| 5oxo-MEHP | −0.006 (−0.007 ; −0.004) | <0.0001 | −0.006 (−0.009 ; −0.004) | <0.0001 | −0.006 (−0.009 ; −0.004) | <0.0001 |

| Total oxidative DEHP metabolites | −0.109 (−0.137 ; −0.081) | <0.0001 | −0.117 (−0.151 ; −0.082) | <0.0001 | −0.118 (−0.156 ; −0.080) | <0.0001 |

| Minimal exposure | ||||||

| 5cx-MEPP | −0.658 (−0.817 ; −0.498) | <0.0001 | −0.738 (−0.957 ; −0.518) | <0.0001 | −0.782 (−1.024 ; −0.541) | <0.0001 |

| 5OH-MEHP | −0.086 (−0.167 ; −0.005) | 0.037 | −0.134 (−0.182 ; −0.086) | <0.0001 | −0.143 (−0.196 ; −0.090) | <0.0001 |

| 5oxo-MEHP | −0.031 (−0.047 ; −0.015) | 0.0002 | −0.042 (−0.054 ; −0.030) | <0.0001 | −0.044 (−0.057 ; −0.030) | <0.0001 |

| Total oxidative DEHP metabolites | −0.678 (−0.946 ; −0.409) | <0.0001 | −0.841 (−1.115 ; −0.567) | <0.0001 | −0.900 (−1.200 ; −0.600) | <0.0001 |

5cx-MEPP: mono-(2-ethyl-5-carboxypentyl) phthalate, 5OH-MEHP: mono-(2-ethyl-5-hydroxyhexyl) phthalate, 5oxo-MEHP: mono-(2-ethyl-5-oxohexyl) phthalate, CI: confidence interval, MEHP: mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate.

Cohort 1 represents all patients who were discharged alive during the Tight Glucose Control (n = 216) and PEPaNIC (n = 334) studies who had DEHP metabolites measured on the last day in PICU.

Cohort 2 represents all patients in the Tight Glucose Control (n = 208) and PEPaNIC (n = 171) studies who had DEHP metabolites measured on the last day in PICU and attention data available at 4-year follow-up.

Estimates are for patients in the PEPaNIC study as compared with those in the Tight Glucose Control study.

Multivariable linear regression analyses were performed with use of standard least squares, adjusting for age at PICU admission, sex, height (Z-score), weight (Z-score), history of malignancy, history of diabetes, and type (cardiac surgery, other surgery or medical reason) and severity (PeLOD score of the first 24 h) of critical illness, with additional adjustment for length of PICU stay for minimal metabolite exposures as outcome.

Multivariable linear regression analyses were performed as in d, further adjusting for race, geographic and linguistic origin, and educational and occupational level of the parents.

3.2. Measures of attention in the PEPaNIC as compared with the Tight Glucose Control study

Of the patients with plasma DEHP metabolite concentrations measured, 208 included in the Tight Glucose Control study and 171 included in the PEPaNIC study had Z-scores of attention measures available 4 years after PICU admission (“Cohort 2”, Fig. 1). Patients in both studies were comparable for sex, age at PICU admission and at follow-up, anthropometrics at PICU admission, geographic origin, language, history of malignancy or diabetes, and length of PICU stay (Table 1). PEPaNIC patients were less frequently known to be non-Caucasian, were less frequently admitted after cardiac surgery and more after non-cardiac surgery, had a higher severity of illness, and the socioeconomic status of their parents was more frequently unknown (with a higher occupational, but not educational level for those from whom the status was known) as compared with those in the Tight Glucose Control study.

In univariable analyses, Z-scores for reaction times with the dominant and non-dominant hand for patients who participated in the PEPaNIC study were not significantly different from those for patients included in the Tight Glucose Control study (Fig. 3). PEPaNIC patients scored worse for consistency of the reaction time with the dominant, but not with the non-dominant hand, as compared with patients in the Tight Glucose Control study. However, adjusted for baseline risk factors, none of the attention measures were significantly different among the two patient groups (Table 3).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of attention measures in the Tight Glucose Control and PEPaNIC studies. Attention was evaluated as reaction time to a visual response and consistency of this reaction time (SD) for both the dominant and the non-dominant hand. Attention measures were compared for all patients with data for DEHP metabolite exposure and data for attention in the TGC group of the Tight Glucose Control study and in the Early-PN group of the PEPaNIC study (Cohort 2, see Fig. 1). Attention measures are expressed as Z-scores, with higher scores reflecting worse performance. Boxes represent medians and interquartile ranges, and whiskers are drawn to the furthest point within 1.5 × IQR from the box. DEHP: di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate, IQR: interquartile range, PN: parenteral nutrition, SD: standard deviation, TGC: tight glucose control.

Table 3.

Multivariable analyses for attention measures as documented 4 years after PICU admission for patients who participated in the PEPaNIC study as compared with those who participated in the Tight Glucose Control study.

| Attention measure a | Scaled estimate (95 %CI) b, c | P |

|---|---|---|

| Dominant hand | ||

| Reaction time (msec) | −14.91 (−43.74 ; 13.91) | 0.30 |

| Consistency (SD) of reaction time (msec) | 1.10 (−24.17 ; 26.37) | 0.93 |

| Non-dominant hand | ||

| Reaction time (msec) | −17.10 (−43.90 ; 9.69) | 0.21 |

| Consistency (SD) of reaction time (msec) | −11.04 (−35.24 ; 13.17) | 0.37 |

SD: standard deviation.

Higher scores for reaction times reflect worse performance.

Estimates are for patients in the PEPaNIC study as compared with those in the Tight Glucose Control study. A negative estimate, provided significance is reached, would point to better attention in the children who participated in the PEPaNIC study as in those who participated in the Tight Glucose Control study and vice versa.

Multivariable linear regression analyses were performed with use of standard least squares, adjusting for age at PICU admission, sex, history of malignancy, history of diabetes, type (cardiac surgery, other surgery or medical reason) and severity (PeLOD score of the first 24 h) of critical illness, race, geographic and linguistic origin, and educational and occupational level of the parents.

To exclude potential selection bias, DEHP metabolite concentrations and minimal exposures were also analyzed in cohort 2. As in Cohort 1, these were significantly lower in the PEPaNIC patients as compared with the patients who participated in the Tight Glucose Control study, both in univariable analyses (Appendix Fig. A.1) and after multivariable adjustment (Table 2). The differences remained after further adjustment for race, geographic origin, language, and occupational and educational levels of the parents. Effect sizes were similar or even larger than in Cohort 1.

To investigate potential bias introduced by tester variability, in view of different pediatric psychologists having evaluated the children's attention in both studies, we used the healthy control children who had been tested in these studies (Appendix Table A.4). Demographically-matched healthy controls who participated in the Tight Glucose Control or PEPaNIC studies were comparable for attention measures, except for a higher inconsistency of the responses with the dominant hand in the PEPaNIC controls as compared with the controls from the Tight Glucose Control study. As expected, patients performed worse than matched healthy controls in both studies. However, the median difference in the attention scores of demographically matched patients and healthy controls in the PEPaNIC study overall was not smaller than the corresponding difference in the Tight Glucose Control study, also not for the measure for which PEPaNIC controls scored worse than the controls in the Tight Glucose Control study (Appendix Table A.5). Hence, the lack of differences in attention measures among patients in the Tight Glucose Control study and PEPaNIC patients is not confounded by tester variability.

4. Discussion

This study showed that plasma concentrations on the last day in the PICU and corresponding minimal exposure of critically ill children to oxidative DEHP metabolites during PICU stay have decreased over the years. Unlike hypothesized, this lower exposure did not translate into an improvement of the pronounced attention deficit that these children are confronted with in the long term, as documented 4 years after PICU admission.

DEHP is known to leach from plastic indwelling medical devices during use, which explains why sometimes even extremely high levels of its metabolites have been found in urine and blood of critically ill patients who highly depend on such devices for survival (Green et al., 2005, Weuve et al., 2006, Huygh et al., 2015, Verstraete et al., 2016). On top of increasing concerns about toxicity of environmental exposure to DEHP, also harm for neurocognitive development of critically ill children had emerged (Tanaka, 2002, Engel et al., 2010, Whyatt et al., 2012, Polanska et al., 2014, Gore et al., 2015, Verstraete et al., 2016, Zarean et al., 2016). After DEHP had already been banned for use in children’s toys, this also urged the restriction of DEHP for use in indwelling plastic medical devices (FDA, 2001, Directive, 2007, SCENIHR, 2015, Gore et al., 2015). Based on two studies performed 8 years apart, we now found that plasma concentrations of the oxidative DEHP metabolites 5cx-MEPP, 5OH-MEHP and 5oxo-MEHP, and corresponding minimal exposures decreased over the years as expected from such a (partial) phase-out. Nevertheless, DEHP was still frequently present in the contemporary plastic medical devices used in the most recent (PEPaNIC) study, but mostly was not the predominant plasticizer found in the devices (Malarvannan et al., 2019). Absolute quantification of DEHP content had not been performed, precluding conclusions on overall exposure (Malarvannan et al., 2019), but the present study supports the active implementation of the stricter rules on the use of DEHP for softening plastic medical devices.

Prenatal or early-life exposure to DEHP has repeatedly been associated with adverse impact on neurocognitive development of children, affecting several functions including IQ (Cho et al., 2010, Huang et al., 2015, Huang et al., 2017), mental and psychomotor developmental indices (Kim et al., 2011, Kim et al., 2018), motor scores (Torres-Olascoaga et al., 2020), attention (Hu et al., 2017), and internalizing and externalizing behavioral problems (Hu et al., 2017, Daniel et al., 2020), among others. In particular, numerous studies have linked DEHP metabolite exposure of children with an increased risk of attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder and severity of associated symptoms, with a negative impact of such exposure on regional cortical maturation (Kim et al., 2009, Chopra et al., 2014, Park et al., 2015, Hu et al., 2017, Engel et al., 2018b, Ku et al., 2020). Children who have been critically ill are also confronted with developmental problems in many of these domains. However, high DEHP metabolite exposure above a certain threshold of potential toxicity appeared to be robustly associated only with the attention problem (explaining half of this deficit), as demonstrated in a development and validation cohort (Verstraete et al., 2016). In view of the lower DEHP metabolite exposure over the years, as documented in the present study, we would have expected that the attention deficit of critically ill children would have become smaller over time. Unfortunately, however, this turned out not to be the case, as the attention deficit 4 years after PICU admission remained as high in the children who participated in the PEPaNIC study as compared with those who participated in the Tight Glucose Control study that had been performed 8 years earlier. Several explanations could theoretically be invoked for the lack of improvement in attention. First, even though exposure to DEHP metabolites during intensive care was lowered over the years, the levels of remaining in-PICU exposure could still be toxic. Second, differences in study populations may have played a role. Even though we adjusted for a whole range of baseline risk factors, we cannot exclude potential residual bias from factors not accounted for. Third, the possibility remains that the previously observed robust independent association of DEHP metabolite exposure with worse attention (Verstraete et al., 2016) reflects a non-causal relationship. Lastly, neurotoxicity of (some of) the alternative plasticizers used to replace DEHP for obtaining soft and flexible plastic indwelling medical devices can at present not be excluded.

For the patient’s care in the PEPaNIC study, plastic indwelling medical devices were used that had been softened with a variety of alternative plasticizers apart from DEHP (Malarvannan et al., 2019). Unfortunately, the devices used during the Tight Glucose Control study had only been tested for the presence of DEHP (Verstraete et al., 2016). However, the use of alternative plasticizers is expected to be less common for that period, since this study had been performed before the implementation of stricter regulations on the use of DEHP. Among the alternative plasticizers, bis(2-ethylhexyl) adipate (DEHA) was detected most frequently, followed by bis(2-ethylhexyl) terephthalate (DEHTP), tris(2-ethylhexyl) trimellitate (TOTM) and tributyl-O-acetyl citrate (ATBC) (Malarvannan et al., 2019). There were also some devices or accessories that contained di-isononyl-cyclohexane-1,2-dicarboxylate (DINCH), di-isononyl phthalate (DiNP), or di-isodecyl phthalate (DiDP) or its isomer di-propylheptyl phthalate (DPHP). Several of these compounds may also leach from the devices. DINCH has been shown to leach from PVC in amounts half those for DEHP (Haishima et al., 2014), urinary DiDP metabolites increased after cardiac surgery (Shang et al., 2019), and low levels of TOTM metabolites have been detected in blood of infants after cardiac surgery (Eckert et al., 2020). Quantification of DEHA, DEHTP, DINCH, and DPHP metabolites in urine of adult ICU patients revealed detectable quantities of almost all metabolites, whereas many were not detected in control samples (Bastiaensen et al., 2019). Detection frequencies in the patients were low, but sampling took place before the increase in the use of alternative plasticizers.

So far, for most of the alternative plasticizers, only few studies about potential toxicity have been performed, with in particular data regarding neurodevelopmental effects being very scarce. Only for DiDP and DINCH, animal studies on direct brain or behavioral effects have been performed. Oral administration of DiDP to mice aggravated the formaldehyde exposure-induced learning and memory impairment, with histopathological alterations in hippocampus (Ge et al., 2019). High doses of DiDP altered the swimming behavior of zebrafish and their circadian rhythm, and decreased acetylcholinesterase activity in brain and other tissues (Poopal et al., 2020). Interference of DiDP with sulfotransferase activity may affect neuronal function via disturbed conversion of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) to DHEA sulfate (Turan et al., 2005, Harris et al., 2007). Intravenous administration of DINCH to rats did not affect their behavior (David et al., 2015). Importantly, lack of data on neurotoxicity of alternative plasticizers does not necessarily mean that these compounds are neurodevelopmentally safe and can be used safely, especially as several have been linked with adverse effects in other toxicity endpoints (Ghisari and Bonefeld-Jorgensen, 2009, Takeshita et al., 2011, Chen et al., 2016, Engel et al., 2018a, Moche et al., 2021). “No observed adverse effect levels” have been proposed for environmental exposures to these plasticizers (Silano et al., 2019), but their extrapolation to the setting of critical illness is cumbersome as impairments in hepatic and renal function may interfere with the clearance of these substances (Verstraete et al., 2016), thus aggravating exposure.

Major strengths of this study include the accuracy of the timing and the duration of the iatrogenic DEHP exposure in relation to the indwelling medical devices, state-of-the art measurement of DEHP metabolite concentrations, as well as the use of highly standardized tests to quantify attentional performance (in contrast to drawing conclusions only based on responses to questionnaires provided by teachers, parents, or guardians as often done in epidemiological studies). Our study also has some limitations. First, the time between both studies amounted to almost a decade, a time window in which some changes in routine management or patient mix could have occurred. Although we limited our study to patients who had received the same glucose control and nutritional management, and adjusted our analyses for dominant premorbid predestinators of neurocognitive function and for the severity of the critical illness, we cannot exclude residual confounding by unaccounted factors. Several risk factors impairing neurocognitive development may at present remain unknown. Also, despite the adjustments made, we cannot exclude that part of the neurocognitive impairment was already present before PICU admission, to a different extent in the patients of both studies, or that post-PICU DEHP or other exposure adversely affecting the brain differed for both study groups, to the disadvantage of the PEPaNIC patients. Ideally, a randomized controlled intervention study is needed to unequivocally prove neurodevelopmental toxicity of exposure to DEHP, but this is still not possible. Indeed, DEHP exposure remains unavoidable with the currently available medical devices, notwithstanding the ethical issue of deliberate random exposure of patients to a potentially toxic compound. Second, neurocognitive testing in the two studies had been performed by different pediatric psychologists. However, we did not observe signs of tester variability. Finally, we only investigated minimal exposure based on plasma concentrations on the last day in PICU and duration of PICU stay, rather than evaluating full, detailed areas under the curve, thus underestimating total exposure. However, we previously demonstrated that the minimal exposure was most discriminative, being robustly associated with neurocognitive outcome, whereas the very high admission peak of DEHP metabolite concentrations (only present very briefly) or area under the curve were not predictive for neurocognitive outcome (Verstraete et al., 2016).

5. Conclusions

Reduced exposure of critically ill children to DEHP during their stay in the PICU did not improve long-term attention problems as documented 4 years after PICU admission. Whether this lack of benefit could be explained by toxicity of the residual DEHP exposure, by toxicity of the alternative plasticizers that were used as replacements of DEHP to soften plastic indwelling medical devices, or by post-PICU environmental exposure to other potentially toxic chemicals, requires further thorough investigation.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ilse Vanhorebeek: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Govindan Malarvannan: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Fabian Güiza: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Giulia Poma: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Inge Derese: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Pieter J. Wouters: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Koen Joosten: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. Sascha Verbruggen: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. Philippe G. Jorens: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. Adrian Covaci: Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Greet Van den Berghe: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the research team members involved in the collection of patient data and blood samples and thank the children and their parents for their willingness to participate in the study.

Funding

This study was supported by the European Research Council (AdvG-2012-321670 and AdvG-2017-785809 to GVdB), the Methusalem program of the Flemish government (METH14/06 to IV and GVdB), Flanders Institute for Science and Technology (IWT-TBM110685, IWT-TBM150181 to GVdB), the Sophia Research Foundation (to SV), Stichting Agis Zorginnovatie (to SV), Erasmus Trustfonds (to SV), and the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN research grant to SV). The study sponsors had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Handling Editor: Olga Kalantzi

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2021.106962.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Ahmadpour D., Mhaouty-Kodja S., Grange-Messent V. Disruption of the blood-brain barrier and its close environment following adult exposure to low doses of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate alone or in an environmental phthalate mixture in male mice. Chemosphere. 2021;282 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagel S., Dessaigne B., Bourdeaux D., Boyer A., Bouteloup C., Bazin J.E., Chopineau J., Sautou V. Influence of lipid type on bis (2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP) leaching from infusion line sets in parenteral nutrition. JPEN J. Parenter. Enteral Nutr. 2011;35:770–775. doi: 10.1177/0148607111414021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banwell B.L., Mildner R.J., Hassall A.C., Becker L.E., Vajsar J., Shemie S.D. Muscle weakness in critically ill children. Neurology. 2003;61:1779–1782. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000098886.90030.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastiaensen M., Malarvannan G., Been F., Yin S., Yao Y., Huygh J., Clotman K., Schepens T., Jorens P.G., Covaci A. Metabolites of phosphate flame retardants and alternative plasticizers in urine from intensive care patients. Chemosphere. 2019;233:590–596. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.05.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T., Yang W., Li Y., Chen X., Xu S. Mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate impairs neurodevelopment: inhibition of proliferation and promotion of differentiation in PC12 cells. Toxicol. Lett. 2011;201:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.-H., Ma L., Hu Y.-X., Wang D.-X., Fang L., Li X.-L., Zhao J.-C., Yu H.-R., Ying H.-Z., Yu C.-H. Transcriptome profiling and pathway analysis of hepatotoxicity induced by tris (2-ethylhexyl) trimellitate (TOTM) in mice. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2016;41:62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S.-C., Bhang S.-Y., Hong Y.-C., Shin M.-S., Kim B.-N., Kim J.-W., Yoo H.-J., Cho I.H., Kim H.-W. Relationship between environmental phthalate exposure and the intelligence of school-age children. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010;118:1027–1032. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopra V., Harley K., Lahiff M., Eskenazi B. Association between phthalates and attention deficit disorder and learning disability in U.S. children, 6–15 years. Environ. Res. 2014;128:64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciellini F., Ferri M., Latini G. Physical-chemical assessment of di-(2-ethylhexyl)-phthalate leakage from poly(vinyl chloride) endotracheal tubes after application in high risk newborns. Int. J. Pharm. 2011;409:57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel S., Balalian A.A., Insel B.J., Liu X., Whyatt R.M., Calafat A.M., Rauh V.A., Perera F.P., Hoepner L.A., Herbstman J., Factor-Litvak P. Prenatal and early childhood exposure to phthalates and childhood behavior at age 7 years. Environ. Int. 2020;143 doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David R.M., White R.D., Larson M.J., Herman J.K., Otter R. Toxicity of Hexamoll(®) DINCH(®) following intravenous administration. Toxicol. Lett. 2015;238:100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2015.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Sonneville L. Boom test uitgevers; Amsterdam: 2014. Handboek Amsterdamse Neuropsychologische Taken. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert E., Müller J., Höllerer C., Purbojo A., Cesnjevar R., Göen T., Münch F. Plasticizer exposure of infants during cardiac surgery. Toxicol. Lett. 2020;330:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2020.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel A., Buhrke T., Kasper S., Behr A.-C., Braeuning A., Jessel S., Seidel A., Völkel W., Lampen A. The urinary metabolites of DINCH ® have an impact on the activities of the human nuclear receptors ERα, ERβ, AR, PPARα and PPARγ. Toxicol. Lett. 2018;287:83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2018.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel S.M., Miodovnik A., Canfield R.L., Zhu C., Silva M.J., Calafat A.M., Wolff M.S. Prenatal phthalate exposure is associated with childhood behavior and executive functioning. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010;118:565–571. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel S.M., Villanger G.D., Nethery R.C., Thomsen C., Sakhi A.K., Drover S.S.M., Hoppin J.A., Zeiner P., Knudsen G.P., Reichborn-Kjennerud T., Herring A.H., Aase H. Prenatal phthalates, maternal thyroid function, and risk of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort. Environ. Health Perspect. 2018;126 doi: 10.1289/EHP2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Union Directive, 2007. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32008R1272.

- FDA . Center for Devices and Radiological Health; Rockville: 2001. Safety assessment of di(2- ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP) released from PVC medical devices. [Google Scholar]

- Fivez T., Kerklaan D., Mesotten D., Verbruggen S., Wouters P.J., Vanhorebeek I., Debaveye Y., Vlasselaers D., Desmet L., Casaer M.P., Garcia Guerra G., Hanot J., Joffe A., Tibboel D., Joosten K., Van den Berghe G. Early versus late parenteral nutrition in critically ill children. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;374:1111–1122. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1514762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Guerra G., Robertson C.M.T., Alton G.Y., Joffe A.R., Dinu I.A., Nicholas D., Ross D.B., Rebeyka I.M. Western Canadian Complex Pediatric Therapies Follow-up Group. Quality of life 4 years after complex heart surgery in infancy. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2013;145:482–488. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayathri N.S., Dhanya A.R., Kurup P.A. Changes in some hormones by low doses of di (2-ethyl hexyl) phthalate (DEHP), a commonly used plasticizer in PVC blood storage bags & medical tubing. Indian J. Med. Res. 2004;119:139–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge S., Yan B., Huang J., Chen Y., Chen M., Yang X., Wu Y., Shen D., Ma P. Diisodecyl phthalate aggravates the formaldehyde-exposure-induced learning and memory impairment in mice. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019;126:152–161. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2019.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghisari M., Bonefeld-Jorgensen E.C. Effects of plasticizers and their mixtures on estrogen receptor and thyroid hormone functions. Toxicol. Lett. 2009;189:67–77. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimeno P., Thomas S., Bousquet C., Maggio A.F., Civade C., Brenier C., Bonnet P.A. Identification and quantification of 14 phthalates and 5 non-phthalate plasticizers in PVC medical devices by GC-MS. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2014;949–950:99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2013.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore A.C., Chappell V.A., Fenton S.E., Flaws J.A., Nadal A., Prins G.S., Toppari J., Zoeller R.T. EDC-2: The Endocrine Society’s Second Scientific Statement on Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals. Endocr. Rev. 2015;36:E1–E150. doi: 10.1210/er.2015-1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green R., Hauser R., Calafat A.M., Weuve J., Schettler T., Ringer S., Huttner K., Hu H. Use of di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate-containing medical products and urinary levels of mono(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate in neonatal intensive care unit infants. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005;113:1222–1225. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haishima Y., Kawakami T., Hasegawa C., Tanoue A., Yuba T., Isama K., Matsuoka A., Niimi S. Screening study on hemolysis suppression effect of an alternative plasticizer for the development of a novel blood container made of polyvinyl chloride. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2014;102:721–728. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.33052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris R., Turan N., Kirk C., Ramsden D., Waring R. Effects of endocrine disruptors on dehydroepiandrosterone sulfotransferase and enzymes involved in PAPS synthesis: genomic and nongenomic pathways. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007;115(Suppl 1):51–54. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hordijk J., Verbruggen S., Vanhorebeek I., Güiza F., Wouters P., Van den Berghe G., Joosten K., Dulfer K. Health-related quality of life of children and their parents 2 years after critical illness: pre-planned follow-up of the PEPaNIC international, randomized, controlled trial. Crit. Care. 2020;24:347. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03059-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu D., Wang Y.-X., Chen W.-J., Zhang Y., Li H.-H., Xiong L., Zhu H.-P., Chen H.-Y., Peng S.-X., Wan Z.-H., Zhang Y., Du Y.-K. Associations of phthalates exposure with attention deficits hyperactivity disorder: A case-control study among Chinese children. Environ. Pollut. 2017;229:375–385. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.05.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H.-B., Chen H.-Y., Su P.-H., Huang P.-C., Sun C.-W., Wang C.-J., Chen H.-Y., Hsiung C.A., Wang S.-L. Fetal and childhood exposure to phthalate diesters and cognitive function in children up to 12 years of age: Taiwanese Maternal and Infant Cohort Study. PLoS ONE. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P.C., Tsai C.H., Chen C.C., Wu M.T., Chen M.L., Wang S.L., Chen B.H., Lee C.C., Jaakkola J.J.K., Wu W.C., Chen M.K., Hsiung C.A., Group R. Intellectual evaluation of children exposed to phthalate-tainted products after the 2011 Taiwan phthalate episode. Environ Res. 2017;156:158–166. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2017.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huygh J., Clotman K., Malarvannan G., Covaci A., Schepens T., Verbrugghe W., Dirinck E., Van Gaal L., Jorens P.G. Considerable exposure to the endocrine disrupting chemicals phthalates and bisphenol-A in intensive care unit (ICU) patients. Environ. Int. 2015;81:64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs A., Dulfer K., Eveleens R., Hordijk J., Van Cleemput H., Verlinden I., Wouters P.J., Mebis L., Garcia Guerra G., Joosten K., Verbruggen S.C., Vanhorebeek I., Van den Berghe G. Long-term developmental impact of withholding parenteral nutrition in paediatric-ICU: a 4-year follow-up of the PEPaNIC randomised controlled trial. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health. 2020;7:503–514. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastner J., Cooper D.G., Maric M., Dodd P., Yargeau V. Aqueous leaching of di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate and “green” plasticizers from poly(vinyl chloride) Sci. Total Environ. 2012;432:357–364. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B.-N., Cho S.-C., Kim Y., Shin M.-S., Yoo H.-J., Kim J.-W., Yang Y.H., Kim H.-W., Bhang S.-Y., Hong Y.-C. Phthalates exposure and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in school-age children. Biol. Psychiatry. 2009;66:958–963. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Eom S., Kim H.-J., Lee J.J., Choi G., Choi S., Kim S., Kim S.Y., Cho G., Kim Y.D., Suh E., Kim S.K., Kim S., Kim G.-H., Moon H.-B., Park J., Kim S., Choi K., Eun S.-H. Association between maternal exposure to major phthalates, heavy metals, and persistent organic pollutants, and the neurodevelopmental performances of their children at 1 to 2years of age- CHECK cohort study. Sci. Total Environ. 2018;624:377–384. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.12.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y., Ha E.-H., Kim E.-J., Park H., Ha M., Kim J.-H., Hong Y.-C., Chang N., Kim B.-N. Prenatal exposure to phthalates and infant development at 6 months: prospective Mothers and Children's Environmental Health (MOCEH) study. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011;119:1495–1500. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1003178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku H.-Y., Tsai T.-L., Wang P.-L., Su P.-H., Sun C.-W., Wang C.-J., Wang S.-L. Prenatal and childhood phthalate exposure and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder traits in child temperament: A 12-year follow-up birth cohort study. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;699 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malarvannan G., Onghena M., Verstraete S., van Puffelen E., Jacobs A., Vanhorebeek I., Verbruggen S.C.A.T., Joosten K.F.M., Van den Berghe G., Jorens P.G., Covaci A. Phthalate and alternative plasticizers in indwelling medical devices in pediatric intensive care units. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019;363:64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.09.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mammen C., Al Abbas A., Skippen P., Nadel H., Levine D., Collet J.P., Matsell D.G. Long-term risk of CKD in children surviving episodes of acute kidney injury in the intensive care unit: a prospective cohort study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2012;59:523–530. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning J.C., Pinto N.P., Rennick J.E., Colville G., Curley M.A.Q. Conceptualizing post intensive care syndrome in children – The PICS-p Framework. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2018;19:298–300. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesotten D., Gielen M., Sterken C., Claessens K., Hermans G., Vlasselaers D., Lemiere J., Lagae L., Gewillig M., Eyskens B., Vanhorebeek I., Wouters P.J., Van den Berghe G. Neurocognitive development of children 4 years after critical illness and treatment with tight glucose control: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;308:1641–1650. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.12424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moche H., Chentouf A., Neves S., Corpart J.-M., Nesslany F. Comparison of in vitro endocrine activity of phthalates and alternative plasticizers. J. Toxicol. 2021;2021:8815202. doi: 10.1155/2021/8815202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S., Lee J.-M., Kim J.-W., Cheong J.H., Yun H.J., Hong Y.-C., Kim Y., Han D.H., Yoo H.J., Shin M.-S., Cho S.-C., Kim B.-N. Association between phthalates and externalizing behaviors and cortical thickness in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychol. Med. 2015;45:1601–1612. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714002694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polanska K., Ligocka D., Sobala W., Hanke W. Phthalate exposure and child development: the Polish Mother and Child Cohort Study. Early Hum. Dev. 2014;90:477–485. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poopal R.-K., Zhang J., Zhao R., Ramesh M., Ren Z. Biochemical and behavior effects induced by diheptyl phthalate (DHpP) and Diisodecyl phthalate (DIDP) exposed to zebrafish. Chemosphere. 2020;252 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.126498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCENIHR . EU; Luxembourg: 2015. ECSCoEaN-IHR opinion on the safety of medical devices containing DEHP-plasticized PVC or other plasticizers on neonates and other groups possibly at risk. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang J., Corriveau J., Champoux-Jenane A., Gagnon J., Moss E., Dumas P., Gaudreau E., Chevrier J., Chalifour L.E. Recovery from a myocardial infarction is impaired in male C57bl/6 N mice acutely exposed to the bisphenols and phthalates that escape from medical devices used in cardiac surgery. Toxicol. Sci. 2019;168:78–94. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfy276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silano V., Barat Baviera J.M., Bolognesi C., Chesson A., Cocconcelli P.S., Crebelli R., Gott D.M., Grob K., Lampi E., Mortensen A., Rivière G., Steffensen I.L., Tlustos C., Van Loveren H., Vernis L., Zorn H., Cravedi J.P., Fortes C., Tavares Poças M.F., Waalkens-Berendsen I., Wölfle D., Arcella D., Cascio C., Castoldi A.F., Volk K., Castle L., EFSA Panel on Food Contact Materials, Enzymes and Processing Aids (CEP) Update of the risk assessment of di-butylphthalate (DBP), butyl-benzyl- phthalate (BBP), bis(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP), di- isononylphthalate (DINP) and di-isodecylphthalate (DIDP) for use in food contact materials. EFSA J. 2019;17:e05838. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2019.5838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeshita A., Igarashi-Migitaka J., Nishiyama K., Takahashi H., Takeuchi Y., Koibuchi N. Acetyl tributyl citrate, the most widely used phthalate substitute plasticizer, induces cytochrome p450 3a through steroid and xenobiotic receptor. Toxicol. Sci. 2011;123:460–470. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T. Reproductive and neurobehavioural toxicity study of bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) administered to mice in the diet. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2002;40:1499–1506. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(02)00073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Olascoaga L.A., Watkins D., Schnaas L., Meeker J.D., Solano-Gonzalez M., Osorio-Valencia E., Peterson K.E., Tellez-Rojo M.M., Tamayo-Ortiz M. Early gestational exposure to high-molecular-weight phthalates and its association with 48-month-old children's motor and cognitive Scores. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:8150. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17218150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turan N., Waring R.H., Ramsden D.B. The effect of plasticisers on “sulphate supply” enzymes. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2005;244:15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstraete S., Vanhorebeek I., Covaci A., Güiza F., Malarvannan G., Jorens P., Van den Berghe G. Circulating phthalates during critical illness in children are associated with long-term attention deficit: a study of a development and a validation cohort. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:379–392. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-4159-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstraete S., Van den Berghe G., Vanhorebeek I. What's new in the long-term neurodevelopmental outcome of critically ill children. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44:649–651. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4968-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstraete S., Verbruggen S.C., Hordijk J.A., Vanhorebeek I., Dulfer K., Güiza F., van Puffelen E., Jacobs A., Leys S., Durt A., Van Cleemput H., Eveleens R.D., Garcia Guerra G., Wouters P.J., Joosten K.F., Van den Berghe G. Long-term developmental effects of withholding parenteral nutrition for 1 week in the paediatric intensive care unit: a 2-year follow-up of the PEPaNIC international. randomised. controlled trial. Lancet. Respir. Med. 2019;7:141–153. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30334-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viner R.M., Booy R., Johnson H., Edmunds J., Hudson L., Bedford H., Kaczmarski E., Rajput K., Ramsay M., Christie D. Outcomes of invasive meningococcal serogroup B disease in children and adolescents (MOSAIC): a case-control study. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:774–783. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70180-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlasselaers D., Milants I., Desmet L., Wouters P.J., Vanhorebeek I., van den Heuvel I., Mesotten D., Casaer M.P., Meyfroidt G., Ingels C., Muller J., Van Cromphaut S., Schetz M., Van den Berghe G. Intensive insulin therapy for patients in paediatric intensive care: a prospective, randomised controlled study. Lancet. 2009;373:547–556. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weuve J., Sanchez B.N., Calafat A.M., Schettler T., Green R.A., Hu H., Hauser R. Exposure to phthalates in neonatal intensive care unit infants: urinary concentrations of monoesters and oxidative metabolites. Environ. Health Perspect. 2006;114:1424–1431. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyatt R.M., Liu X., Rauh V.A., Calafat A.M., Just A.C., Hoepner L., Diaz D., Quinn J., Adibi J., Perera F.P., Factor-Litvak P. Maternal prenatal urinary phthalate metabolite concentrations and child mental, psychomotor, and behavioral development at 3 years of age. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012;120:290–295. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You M., Dong J., Fu Y., Cong Z., Fu H., Wei L., Wang Y., Wang Y., Chen J. Exposure to di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate during perinatal period gender-specifically impairs the dendritic growth of pyramidal neurons in rat offspring. Front. Neurosci. 2018;12:444. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarean M., Keikha M., Poursafa P., Khalighinejad P., Amin M., Kelishadi R. A systematic review on the adverse health effects of di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2016;23:24642–24693. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-7648-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.