Abstract

Bio-manufacturing via microbial cell factory requires large promoter library for fine-tuned metabolic engineering. Ogataea polymorpha, one of the methylotrophic yeasts, possesses advantages in broad substrate spectrum, thermal-tolerance, and capacity to achieve high-density fermentation. However, a limited number of available promoters hinders the engineering of O. polymorpha for bio-productions. Here, we systematically characterized native promoters in O. polymorpha by both GFP fluorescence and fatty alcohol biosynthesis. Ten constitutive promoters (PPDH, PPYK, PFBA, PPGM, PGLK, PTRI, PGPI, PADH1, PTEF1 and PGCW14) were obtained with the activity range of 13%–130% of the common promoter PGAP (the promoter of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase), among which PPDH and PGCW14 were further verified by biosynthesis of fatty alcohol. Furthermore, the inducible promoters, including ethanol-induced PICL1, rhamnose-induced PLRA3 and PLRA4, and a bidirectional promoter (PMal-PPer) that is strongly induced by sucrose, further expanded the promoter toolbox in O. polymorpha. Finally, a series of hybrid promoters were constructed via engineering upstream activation sequence (UAS), which increased the activity of native promoter PLRA3 by 4.7–10.4 times without obvious leakage expression. Therefore, this study provided a group of constitutive, inducible, and hybrid promoters for metabolic engineering of O. polymorpha, and also a feasible strategy for rationally regulating the promoter strength.

Keywords: GFP, Green Fluorescent Protein; UAS, Upstream Activation Sequence; EMP, Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas pathway

Keywords: Ogataea polymorpha, Promoter, Hybrid promoter, Upstream activation sequence, Metabolic engineering, Fatty alcohols

1. Introduction

Bio-manufacturing represents for a promising approach for sustainable supplying of chemicals with mild reaction conditions, low energy consumption [1]. Microbial cell factories with extensive metabolic engineering have been applied for productions of bulk chemicals [2] and natural products [3,4]. Construction of biosynthetic pathways requires expression of multiple genes, which is normally realized by different promoters with various strengths. Besides, fine-tuning metabolic flux, including overexpression and down-regulation of key genes [5], directed evolution of enzymes [6], cofactor engineering [7], and so on, reduce the toxic intermediates and enhance the production of target products. Consequently, the convenient and commonly used transcriptional regulation via a large promoter library guarantees a superior microbial cell factory for efficient productions [[8], [9], [10]].

Ogataea polymorpha (hereafter O. polymorpha), a methylotrophic yeast, has a broad spectrum of substrates like glucose, xylose, glycerol, methanol, and high thermo-tolerance [11]. For example, high temperature (45 °C) fermentation enabled efficient ethanol production from xylose in O. polymorph [11]. In addition, the characteristics of O. polymorpha in post-translational modification and high-density fermentation make it a promising candidate to produce heterologous proteins [12]. However, there is limited reports on chemicals production in O. polymorpha, which may be partially attributed to the poor genetic manipulation tools and promoter library [13].

Recently, CRISPR/Cas9 based genome editing system was established for O. polymorpha [[14], [15], [16]]. While the promoter lack situation is still remaining and seriously hinders the extensive metabolic engineering of O. polymorpha [17]. Generally, promoters are classified into constitutive and inducible promoters. Constitutive promoters possess basically stable activities among different fermentative conditions. The strength of inducible, or repressive promoters are dynamic regulated by specific inducers or repressors. Promoters commonly used for gene expression in O. polymorpha includes the strong methanol-induced promoter PAOX1 (the promoter of alcohol oxidase I gene) and promoter PFMD (the promoter of formate dehydrogenase gene) [18,19], and the strong constitutive promoter PGAP (the promoter of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene) [20]. Obviously, these limited tools are far from enough for extensive metabolic engineering. Therefore, further screening other available promoters in O. polymorpha is essential, which should promote its potential as a chassis host in protein and chemicals production.

In this study, green fluorescent protein (GFP) was used to characterize the promoter strength (Fig. S1). A total of ten constitutive promoters were characterized, among which the promoters PGCW14 and PPDH were further verified by production of fatty alcohol. Additionally, multiple inducible promoters were evaluated, and the regulation of promoter activity was achieved by constructing tandem repeats of upstream activation sequence (UAS), generating hybrid promoters with greatly enhanced activities [[21], [22], [23]]. Overall, our results offered a promoter toolbox with distinguished activities, and a feasible strategy to control promoter activities in O. polymorpha, which will pave the way to adopt this superior host for extensive metabolic engineering in both fundamental and industrial applications.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Strains and media

All strains used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S1. YPD medium contains 10 g/L yeast extract, 20 g/L peptone and 20 g/L glucose. LB medium was composed of 5 g/L yeast extract, 10 g/L NaCl and 10 g/L tryptone. 100 mg/mL ampicillin or 50 μg/mL chloramphenicol was added to LB medium depending on the resistance of the plasmids. Synthetic Dropout (SD) medium containing 20 g/L glucose and 6.7 g/L amino acid-free yeast nitrogen source (YNB) were used for strain screening during transformation, and 60 mg/L l-leucine was added into SD medium when necessary. Basic salt (Delft) medium was adopted to cultivate O. polymorpha strains [24], containing 2.5 g/L (NH4)2SO4, 14.4 g/L KH2PO4, 0.5 g/L MgSO4•7H2O, 2 mL/L trace metals, 1 mL/L vitamin solution and one of the following carbon sources, 20 g/L glucose (Delft-Glu), 20 g/L l-rhamnose (Delft-Rha), 10 g/L xylose (Delft-Xyl), 10 g/L methanol (Delft-MeOH), 30 g/L ethanol (Delft-EtOH), 10 g/L glycerol (Delft-Gly), or 20 g/L sucrose (Delft-Suc). 20 mg/L uracil, or/and 60 mg/L l-leucine was supplemented when necessary. For solid plates, 20 g/L agar was used.

2.2. Genetic engineering

Plasmids and primers used in this study were listed in Table S2 and Table S3, respectively. Genetic manipulation was achieved by using our previously reported CRISPR/Cas9 system in O. polymorpha [15]. Gene expression cassettes were constructed by overlap extension PCR and integrated into neutral sites of O. polymorpha [25]. For screening of constitutive promoters from glycolysis pathway (EMP) and inducible promoters, purified donor DNA including GFPuv gene, promoter, terminator (TCYCY), upstream and downstream homologous arms, was introduced into NS2 site of strain JQCr03. For characterization of PGCW14 and construction of the hybrid promoters, strain Yan01 was used, with in situ complementation of OpLEU2 gene in strain JQCr03. To minimize the detection errors, eGFP expression cassette was integrated into NS3 site in Yan01 strain.

2.3. DNA transformation of O. polymorpha

Electroporation was carried out for transformation of O. polymorpha according to previous procedures with slight modifications [26]. Briefly, cell culture with OD600 of 0.8–1.0 was transferred into a 15 mL tube, and centrifuged at 3000 g for 5 min. Cell pellets was resuspended in 4 mL sterile 50 mM PBS buffer (pH 7.5) supplemented with 25 mM dithiotreitol (DTT). After incubation at 37 °C for 15 min, cells were washed twice with ice-cold STM buffer (270 mM sucrose, 10 mM Tris-HC1 pH 7.5 and 1 mM MgC12). Cells were resuspended in cold STM solution to obtain competent cells. 50 μL competent cells were mixed with 500 ng donor DNA and 500 ng gRNA plasmid, and transferred into a prechilled 2-mm electroporation cuvette, and electroporated in MicroPulser (Bio-rad) under “PIC” model. Cells were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h, washed with ddH2O, plated on the selective SD plates, and then incubated at 37 °C for 3–4 days.

2.4. Fluorescence assay

GFP expression strains were cultured in Delft medium containing different carbon sources at 37 °C, 220 rpm. Samples were taken at 24 h, 48 h and 72 h and then diluted to optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.2–0.8 to measure biomass and fluorescence intensity. Fluorescence values were measured by TECAN spark (TECAN, Switzerland). The excitation wavelengths of GFPuv and eGFP were 396 nm and 485 nm and the emission wavelengths were 510 nm and 525 nm, respectively.

2.5. Production and detection of fatty alcohol

As shown in Fig. 3A, a modular engineering strategy was used to construct fatty alcohol biosynthetic pathway [27]. To promote accumulation of fatty acids and fatty aldehydes, hexadecenal dehydrogenase (encoded by HFD1) and fatty acyl-CoA synthase (encoded by FAA1) were both disrupted in strain Yan01, obtaining strain Yan03. For fatty alcohol production, CAR and its co-factor NpgA, and ADH5 were codon optimized and heterologously expressed in O. polymorpha, of which ADH5 and NpgA were integrated at NS2 site, obtaining strain Yan04. To evaluate the effect of promoters on fatty alcohol production, CAR was expressed under the control of PGAP, PGCW14 or PPDH, and were integrated at NS3 site in strain Yan04. All strains were pre-cultivated in YPD medium for 24 h, and then transferred into Delft medium containing 20 g/L glucose and cultivated at 37 °C, 220 rpm. Fatty alcohols were measured according to previous methods after 120 h cultivation [[25], [26], [27]].

Fig. 3.

Biosynthesis of fatty alcohol under the control of promoter PGCW14 and PPDH. (A) To promote accumulation of fatty acids and fatty aldehydes, hexadecenal dehydrogenase (encoded by HFD1) and fatty acylCoA synthase (encoded by FAA1) were disrupted, and codon-optimized ADH5 and NpgA were integrated into NS2 site. CAR gene under control of various promoters (PGAP, PGCW14 or PPDH) were integrated into NS3 site. All strains were pre-cultured in YPD medium for 24 h, and then transferred into Delft medium containing 20 g/L glucose and cultivated at 37 °C, 220 rpm for 120 h. Production of fatty alcohols were measured after 120 h cultivation (B). All data was presented as the mean ± s.d. of three clones.

2.6. Determine the promoter upstream activation sequence

Core promoter region and binding sites of were transcription factors were analyzed online (http://www.fruitfly.org/seq_tools/promoter.html) [28] and (http://gene-regulation.com/pub/programs/alibaba2/index.html) [29]. To determine the region of upstream activation sequence (UAS), promoters were truncated according to the transcription factor binding sites (Fig. S2). The truncated promoters were characterized by the fluorescence intensity of eGFP.

2.7. Construction of hybrid promoters

Hybrid promoters were constructed by Golden-gate assembly using BsaI-HF®v2 kit (New England Biolabs, USA). Fragments of PLRA3 and UAS-PLRA3 were amplified using primers in Table S3, containing the recognition sites of BsaI and four additional bases. The fragments were ligated together and transformed into Escherichia coli competent cells, which were screened on plates of LB + Chl (chloramphenicol) for 12–16 h. The correct colonies were verified by PCR and Sanger sequencing. The hybrid promoters were amplified and inserted into plasmid Hp01-eGFP and integrated into NS3 site of O. polymorpha for further characterization.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of native constitutive promoters of O. polymorpha

In yeasts, the commonly used constitutive promoters are PGAP, the promoter of alcohol dehydrogenase (PADH1), the promoter of translation elongation factor (PTEF1), and so on [30]. To test our characterization system, these promoters were first quantified in glucose and methanol media by the normalized fluorescence intensity. As expected, the promoter PGAP was the strongest constitutive promoter, which was 1.7-fold, and 4.3-fold higher than PADH1 and PTEF1, respectively (Fig. 1A). In methanol medium, the strength of PADH1 and PTEF1 was 37% and 26% of PAOX1 (Fig. 1B), a strong methanol induced promoter [31].

Fig. 1.

Characterization of constitutive promoters in glucose and methanol cultures. eGFP was used as the characterization protein and the expression box was integrated at the neutral site (NS3). Engineered strains were cultivated in both 20 g/L glucose for 48 h (A), and 10 g/L methanol for 72 h (B). On this basis, seven promoters from glycolysis pathway were selected to test their activities. GFPuv under control of different promoters was integrated at neutral site (NS2). Engineered strains were cultivated in both 20 g/L glucose for 48 h (C), and 10 g/L methanol for 72 h (D). The starting strain without promoter integration was taken as negative control (Ctrl), and native promoter PGAP and PAOX1 from O. polymorpha are positive controls (100%) to normalize the fluorescence values of other promoters. All data was represented as the mean ± s.d. of three clone samples. Abbreviations of PGene X means the promoter of a specific gene, including glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAP), alcohol oxidase (AOX1), translation elongation factor (TEF1), alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH1), hexokinase (GLK), glucose 6 - phosphate isomerase (GPI), fructose 1,6 - bisphosphate aldolase (FBA), triosephosphate isomerase (TRI), phosphoglycerate mutase (PGM), pyruvate kinase (PYK), and pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH). Red asterisks indicate statistical significance as determined using paired t-test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001).

To further explore constitutive promoters in O. polymorpha, we characterized the promoters of genes from the glycolysis pathway (Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas pathway, EMP). EMP is a common pathway in most organisms to assimilate hexose for the generation of intermediates and energy, in which most genes are constitutively expressed for cell growth [32]. Therefore, a total of 7 native gene promoters from EMP was characterized. Generally, statistical analysis indicated that there was a significant difference in fluorescence intensity between the control strain and the engineered strains, which demonstrated that all these promoters possessed the transcriptional activities (Fig. 1C and D). In glucose culture, the promoter activity ranged from 13% to 42% of PGAP with a strength order of PPDH > PPYK > PFBA > PPGM > PGLK > PTRI > PGPI, (Fig. 1C). While in methanol culture, the promoter strength were 8%–42% of PAOX1 with an order of PTRI > PFBA > PPDH > PPYK >PPGM > PGPI > PGLK (Fig. 1D). Most promoters from EMP like PFBA, PTRI, PPYK, and PPDH had the comparable strength to PADH1 and PTEF1 in either glucose or methanol culture, which demonstrated the availability of these promoters for gene expression. Interestingly, the relative activities of constitutive promoters varied among different conditions (comparing Fig. 1A and B, Fig. 1C and D). These promoters with distinguished activities might expand biological elements for the precise regulation of metabolic engineering in O. polymorpha.

In addition to the promoters of glycolysis, the promoter of a predicted glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchored protein (encoded by gene GCW14) was proved to be a strong constitutive promoter in Pichia pastoris (hereafter P. pastoris) [33,34]. Here, a promoter with the length of 882 bp was identified as PGCW14 by sequence similarity in O. polymorpha, and subsequently characterized to evaluate activities under various conditions. The enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) was used here instead of GFPuv due to its limited intensity. Promoter PGCW14 from O. polymorpha and P. pastoris were both tested by using the promoters PGAP and PAOX1 as the positive control. The native promoter PGCW14 had very high activity, which was 1.3 times higher than PGAP in glucose and 1.1 times higher than PAOX1 in methanol (Fig. 2A and B). Surprisingly, the promoter PPpGCW14 from P. pastoris was also functional in O. polymorpha with about half of the activity of PGCW14. Subsequently, activities of promoter PGCW14 was characterized in media containing different carbon sources including glucose, xylose, methanol, ethanol, and glycerol. Similar strengths were achieved under these cultivation conditions, which further proved that PGCW14 was a strong constitutive promoter (Fig. 2C). A decreased activity of PGCW14 with time, especially in glucose and glycerol, was observed, which might be related to cell viability (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Characterization of promoter PGCW14 under different carbon sources. Promoter of gene GCW14 (predicted GPI anchored protein) from both O. polymorpha (PGCW14) and P. pastoris (PPpGCW14) were selected to drive eGFP expression at neutral site NS3. Engineered strains were cultivated with 20 g/L glucose for 48 h (A) or 10 g/L methanol for 72 h (B). The original strain without promoter integration was taken as negative control (Ctrl), and native promoter PGAP and PAOX1 from O. polymorpha are positive controls (100%) to normalize the fluorescence values of other promoters. (C) Promoter PGCW14 was evaluated under 10 g/L of multiple carbon sources, and samples were taken at 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h, respectively, to measure fluorescence values. All data was represented as the mean ± s.d. of three clones.

3.2. Construction of fatty alcohol biosynthetic pathway using constitutive promoters

Most promoters were characterized based on fluorescence intensity of eGFP [35]. However, when applied in metabolic engineering, the biosynthetic efficiency may be not well correlated with fluorescence intensity driven by the same promoter. In order to better characterize the applicability of the above promoters, promoter PPDH with a medium strength from EMP pathway and the strong constitutive promoter PGCW14 were selected for construction of biosynthetic pathway of fatty alcohol, which is a bulk chemical widely-used for production of lubricants, skin care products and plastics [36]. The pathway for fatty alcohol synthesis is illustrated in Fig. 3A. Deletions of fatty acyl-CoA synthetase (encoded by FAA1) and fatty aldehyde dehydrogenase (encoded by HFD1) promoted the accumulation of fatty aldehydes and fatty acids, which provided sufficient precursors for fatty alcohol production. The carboxylic acid reductase gene CAR was expressed with different promoters, since fatty acid reduction was showed to be the limited step in fatty alcohol synthesis [27]. In detail, CAR was drove by PPDH, PGCW14 or PGAP, respectively, and NpgA and ScADH5 was expressed under the control of PGAP and PTEF1 with genome-integrated at neutral site NS2 [25]. The fatty alcohol titers were 8.9 mg/L and 11.2 mg/L with CAR overexpression driven by PPDH and PGCW14, respectively, which was 55% and 69% of the titer in strain containing gene CAR driven by PGAP (Fig. 3B). These results showed that promoters were functional for an efficient biosynthesis and metabolic regulation of target products.

3.3. Characterizing inducible promoters from O. polymorpha

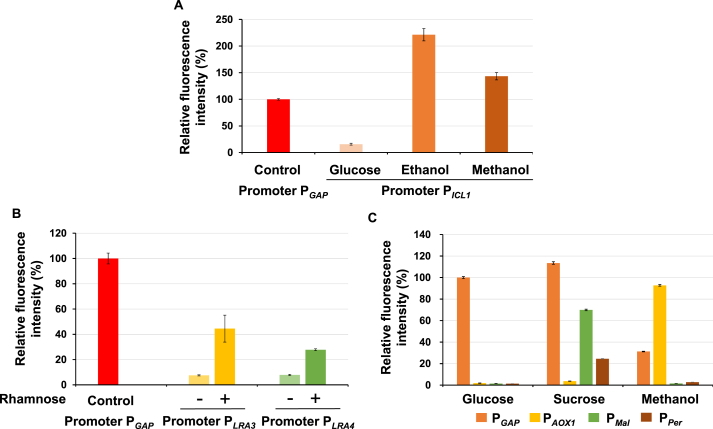

Fine-tuned metabolic engineering like time-sequential regulation and toxicity decrease requires extensive inducible promoters, such as methanol-induced PAXO1 [37]. Hence, to further enrich the limited inducible promoter in O. polymorpha, promoter PICL1 (the promoter of isocitrate lyase gene, 680 bp) [38], PLRA3 (the promoter of l-rhamnonate dehydratase gene, 210 bp) and PLRA4 (the promoter of L-2-keto-3-deoxyrhamnonate (L-KDR) aldolase gene, 210 bp) [39], and PMal (the promoter of maltase, 1434 bp) [40], were evaluated. All these promoters demonstrated distinguished performances while cultivating in different carbon sources (Fig. 4). Interestingly, promoter PICL1 was strongly activated by both ethanol and methanol with up to twice activity of PGAP (Fig. 4A), which demonstrated glyoxylate bypass that gene ICL1 mainly functions in may play a vital role in the assimilation of short-chain alcohols. Similarly, promoter PLRA3 and PLRA4 were both induced by rhamnose, whose activity was 44% and 28% of PGAP, respectively (Fig. 4B). As reported in Ogataea thermomethanolica [40], the bidirectional promoter PMal-PPer in O. polymorpha was also strictly repressed by both glucose and methanol, and achieved 70% and 24% of the strength of PGAP, respectively, in sucrose (Fig. 4C). Consequently, all these inducible promoters with a diverse strength were suitable for metabolic rewiring at different levels.

Fig. 4.

Characterization of inducible promoters by eGFP fluorescence intensities in O. polymorpha. (A) Inducible promoter PICL1 were characterized in Delft medium containing 20 g/L glucose, or 30 g/L ethanol, or 10 g/L methanol. (B) Inducible promoters PLRA3 and PLRA4 were characterized under inducible (20 g/L rhamnose) and non-inducible (20 g/L glucose) conditions. (C) Bidirectional promoter (PMal-PPer) was characterized in Delft medium containing 20 g/L glucose, 20 g/L sucrose or 10 g/L methanol, respectively. Strains were cultivated at 37 °C, 220 rpm, and samples were taken at 48 h to measure the biomass and fluorescence. Results were normalized by fluorescence intensity of PGAP cultivated with 20 g/L glucose (100%). All data was represented as the mean ± s.d. of three clones.

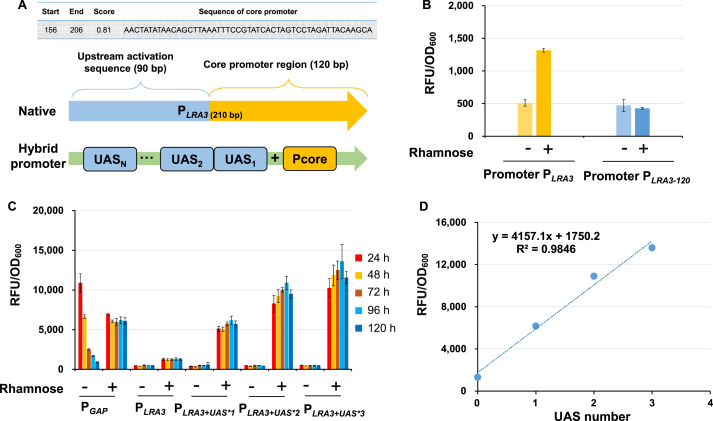

3.4. Construction of hybrid inducible promoter

Construction of hybrid promoters represents a feasible solution to obtain a preferred promoter based on practical demands [41,42]. Here, we tried to construction of an artificial hybrid promoter based on promoter PLRA3. Promoters usually consist of upstream activation sequence (UAS) regions and core promoter regions. UAS determines the transcription efficiency, which is usually adopted to enhance the promoter strength [35]. To determine the UAS region of promoters PGAP and PADH1, stepwise truncation strategy was used based on sequence prediction (Fig. S2A). To avoid the disruption of transcriptional binding sites and core promoter region, PGAP and PADH1 were cut to 3 and 4 truncated promoters, respectively. UAS regions of PGAP and PADH1 were defined as the region of -336∼-110 bp, and -125∼-680 bp, respectively, according to GFP fluorescence (Fig. S3A). Subsequently, the hybrid promoter was constructed by combining promoter PLRA3 with the UAS regions of PGAP and PADH1, respectively. As shown in Fig. S3B, the hybrid promoter UASPADH1 + PLRA3 seemed to promote the strength with no influence on inductivity. However, the correspondingly increased activity in glucose demonstrated that a direct combination of core promoter with UAS region from another promoter resulted in expression leakage (Fig. S3B).

It has been reported that a tandem UAS contributed to an enhanced promoter strength [43]. Therefore, another hybrid inducible promoter was constructed by combining PLRA3 with its own UAS. Firstly, as shown in Fig. 5A and Fig. S2B, promoter PLRA3 was truncated according to the predicted core sequence and transcriptional binding sites, and 90 bp UAS region (-210 bp∼-120 bp) of PLRA3 was identified (Fig. 5B). Then, 1–3 UAS regions were placed upstream of the promoter PLRA3 [21,22]. Excitingly, the hybrid promoters had dramatically higher strength and the hybrid promoter PLRA3+UAS*3 with three copies of UAS had maximum fluorescence intensity, 10.4 times higher compared with the original promoter PLRA3 at 96 h (Fig. 5C). The activity of PLRA3+UAS*3 was twice higher than that of PGAP and the promoter activities were positively correlated with the numbers of UAS regions (R2 = 0.98, Fig. 5D), which demonstrated great application potential of the tandem UAS in promoter regulation.

Fig. 5.

Fluorescence characterization of hybrid promoters. (A) Determination of upstream activation sequence (UAS) and core region of promoter PLRA3 by stepwise truncation strategy, and the construction of hybrid promoters by UAS tandem strategy. (B) Characterization of PLRA3 and truncated PLRA3under inducible (20 g/L rhamnose) and non-inducible (20 g/L glucose) conditions. (C) Characterization of PLRA3 and hybrid promoters PLRA3+UAS*1, PLRA3+UAS*2, PLRA3+UAS*3. All promoters were evaluated by fluorescence values under inducible (20 g/L rhamnose) and non-inducible (20 g/L glucose) conditions at 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, 96 h, and 120 h. Promoter PGAP was used as the positive control. (D) Correlation between promoter strength and numbers of UAS series. All data was represented as the mean ± s.d. of three clones.

4. Discussion

Availability of promoters is very essential for extensive metabolic engineering. This study identified and characterized three different types of native promoters (constitutive, inducible and hybrid) in O. polymorpha for further constructions of cell factory, and also provides a feasible strategy for promoter mining and control.

We characterized several endogenous constitutive promoters from central metabolic pathways, which however was much weaker compared with the strong constitutive promoter PGAP (10%–60%). We here found the promoter strength was varied between glucose and methanol, which demonstrated that these promoters are not strictly constitutive, and may be related to cell growth status under various fermentative conditions. In addition, a strong constitutive promoter PGCW14 of a potential glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchored protein, which is not related to specific pathway, was characterized to be a relatively constitutive promoter under different culture conditions. Interestingly, a homologous promoter PPpGCW14 from P. pastoris was also functional in O. polymorpha. This universal expression regulation among different yeasts may provide a reference strategy for further mining similar promoters with different intensities [33].

To further expand the promoter library in O. polymorpha, the inducible promoters were excavated, including ethanol-induced promoter PICL1, rhamnose-induced promoters PLRA3 and PLRA4, and a bidirectional promoter PMal-PPer. These inducible promoters demonstrated strict glucose repression, and even though in a mixture of glucose and inducers, the activity remained an extremely low level. Just like GAL system in S. cerevisiae [44], these inducible promoters may be regulated by other transcriptional factors, and their regulatory mechanisms are worthy of further exploration by a more refined stepwise truncation strategy [45]. We also found that the strength of the inducible promoter such as PLRA3 was relatively low. A UAS-tandem strategy was developed to increase the promoter strength of PLRA3 by 4.7–10.4 times without influencing the inducible feature. Compared with the site-directed mutagenesis approach [46], this rational design may directly obtain the hybrid promoter with a predictable manner [35,47]. We can expect that our hybrid promoter strategy can be applied to other large number of inducible promoters with low strengths.

We also used various promoters PPDH and PGCW14 for regulating the biosynthesis of fatty alcohols. The positive relation between promoter strength and fatty alcohol production verified the practicability of promoter based pathway regulation. Larger number of promoters with various strengths can help to regulate the metabolic pathways with a precise manner, which should be helpful for optimization of metabolic network in cell factory construction [48].

In summary, we identified and evaluated three different types of promoters for providing sound biological elements in metabolic engineering of O. polymorpha, as well as provided feasible strategies for promoters mining and engineering.

Availability of data and material

Data that supports the finding of this study are available in the main text and the supplementary materials.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent for publication

All listed authors have approved the manuscript before submission, including the names and order of authors.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Chunxiao Yan: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Wei Yu: Methodology, Resources. Xiaoxin Zhai: Methodology, Resources. Lun Yao: Methodology, Resources. Xiaoyu Guo: Writing – review & editing. Jiaoqi Gao: Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Yongjin J. Zhou: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The work was financially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (21808216, 22161142008 and M-0246), Key project at central government level: The ability establishment of sustainable use for valuable Chinese medicine resources (2060302) and DICP innovation grant (DICP I202021 and I201920) from Dalian Institute of Chemicals Physics, CAS.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of KeAi Communications Co., Ltd.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.synbio.2021.12.005.

Contributor Information

Xiaoyu Guo, Email: gxycw0102@dlpu.edu.cn.

Jiaoqi Gao, Email: jqgao@dicp.ac.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Zhou Y.J., Kerkhoven E.J., Nielsen J. Barriers and opportunities in bio-based production of hydrocarbons. Nat Energy. 2018;3:925–935. doi: 10.1038/s41560-018-0197-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biz A., Proulx S., Xu Z., Siddartha K., Mulet Indrayanti A., Mahadevan R. Systems biology based metabolic engineering for non-natural chemicals. Biotechnol Adv. 2019;37:107379. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2019.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen R., Yang S., Zhang L., Zhou Y.J. Advanced strategies for production of natural products in yeast. IScience. 2020;23 doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2020.100879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lv X., Wang F., Zhou P., Ye L., Xie W., Xu H., et al. Dual regulation of cytoplasmic and mitochondrial acetyl-CoA utilization for improved isoprene production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12851. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peng B., Plan M.R., Carpenter A., Nielsen L.K., Vickers C.E. Coupling gene regulatory patterns to bioprocess conditions to optimize synthetic metabolic modules for improved sesquiterpene production in yeast. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2017;10:43. doi: 10.1186/s13068-017-0728-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johannes T.W., Zhao H. Directed evolution of enzymes and biosynthetic pathways. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2006;9:261–267. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Y., Bao J., Kim I.K., Siewers V., Nielsen J. Coupled incremental precursor and co-factor supply improves 3-hydroxypropionic acid production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Metab Eng. 2014;22:104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engstrom M.D., Pfleger B.F. Transcription control engineering and applications in synthetic biology. Synth Syst Biotechnol. 2017;2:176–191. doi: 10.1016/j.synbio.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown S., Clastre M., Courdavault V., O'Connor S.E. De novo production of the plant-derived alkaloid strictosidine in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:3205–3210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423555112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paddon C.J., Westfall P.J., Pitera D.J., Benjamin K., Fisher K., McPhee D., et al. High-level semi-synthetic production of the potent antimalarial artemisinin. Nature. 2013;496:528–532. doi: 10.1038/nature12051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurylenko O.O., Ruchala J., Vasylyshyn R.V., Stasyk O.V., Dmytruk O.V., Dmytruk K.V., et al. Peroxisomes and peroxisomal transketolase and transaldolase enzymes are essential for xylose alcoholic fermentation by the methylotrophic thermotolerant yeast, Ogataea (Hansenula) polymorpha. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2018;11:197. doi: 10.1186/s13068-018-1203-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manfrão-Netto J.H.C., Gomes A.M.V., Parachin N.S. Advances in using Hansenula polymorpha as chassis for recombinant protein production. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2019;7:94. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2019.00094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao L., Cai P., Zhou Y.J. Advances in metabolic engineering of methylotrophic yeasts. Shengwu Gongcheng Xuebao/Chin J Biotechnol. 2021;37:966–979. doi: 10.13345/j.cjb.200645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang L., Deng A., Zhang Y., Liu S., Liang Y., Bai H., et al. Efficient CRISPR-Cas9 mediated multiplex genome editing in yeasts. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2018;11:1–16. doi: 10.1186/s13068-018-1271-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao J., Gao N., Zhai X., Zhou Y.J. Recombination machinery engineering for precise genome editing in methylotrophic yeast Ogataea polymorpha. iScience. 2021;24:102168. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.102168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cai P., Duan X., Wu X., Gao L., Ye M., Zhou Y.J. Recombination machinery engineering facilitates metabolic engineering of the industrial yeast Pichia pastoris. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:7791–7805. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen X., Gao C., Guo L., Hu G., Luo Q., Liu J., et al. DCEO biotechnology: tools to design, construct, evaluate, and optimize the metabolic pathway for biosynthesis of chemicals. Chem Rev. 2018;118:4–72. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gellissen G., Hollenberg C.P. Application of yeasts in gene expression studies: a comparison of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Hansenula polymorpha and Kluyveromyces lactis - a review. Gene. 1997;190:87–97. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(97)00020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wetzel D., Müller J.M., Flaschel E., Friehs K., Risse J.M. Fed-batch production and secretion of streptavidin by Hansenula polymorpha: evaluation of genetic factors and bioprocess development. J Biotechnol. 2016;225:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2016.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krasovska O.S., Stasyk O.G., Nahorny V.O., Stasyk O.V., Granovski N., Kordium V.A., Vozianov O.F., Sibirny A.A. Glucose-induced production of recombinant proteins in Hansenula polymorpha mutants deficient in catabolite repression. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2006;97:858–870. doi: 10.1002/bit.21284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamedirad M., Weisberg S., Chao R., Lian J., Zhao H. Highly efficient single-pot scarless golden gate assembly. ACS Synth Biol. 2019;8:1047–1054. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.8b00480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tong Y., Zhou J., Zhang L., Xu P. A golden-gate based cloning toolkit to build violacein pathway libraries in Yarrowia lipolytica. ACS Synth Biol. 2021;10:115–124. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.0c00469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larroude M., Rossignol T., Nicaud J.M., Ledesma-Amaro R. Synthetic biology tools for engineering Yarrowia lipolytica. Biotechnol Adv. 2018;36:2150–2164. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2018.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verduyn C., Postma E., Scheffers W.A., Van Dijken J.P. Effect of benzoic acid on metabolic fluxes in yeasts: a continuous‐culture study on the regulation of respiration and alcoholic fermentation. Yeast. 1992;8:501–517. doi: 10.1002/yea.320080703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu W., Gao J., Zhai X., Zhou Y.J. Screening neutral sites for metabolic engineering of methylotrophic yeast Ogataea polymorpha. Synth Syst Biotechnol. 2021;6:63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.synbio.2021.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Faber K.N., Haima P., Harder W., Veenhuis M., Ab G. Highly-efficient electrotransformation of the yeast Hansenula polymorpha. Curr Genet. 1994;25:305–310. doi: 10.1007/BF00351482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou Y.J., Buijs N.A., Zhu Z., Qin J., Siewers V., Nielsen J. Production of fatty acid-derived oleochemicals and biofuels by synthetic yeast cell factories. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11709. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reese M.G. Application of a time-delay neural network to promoter annotation in the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Comput Chem. 2001;26:51–56. doi: 10.1016/S0097-8485(01)00099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grabe Niels. AliBaba2: context specific identification of transcription factor binding sites. In Silico Biol. 2002;2(1):S1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhai X., Ji L., Gao J., Zhou Y.J. Characterizing methanol metabolism-related promoters for metabolic engineering of Ogataea polymorpha. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2021:8761–8769. doi: 10.1007/s00253-021-11665-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ledeboer A.M., Edens L., Maat J., Visser C., Bos J.W., Verrips C.T., et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of a gene coding for methanol oxidase in Hansenula polymorpha. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:3063–3082. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.9.3063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fernie A.R., Carrari F., Sweetlove L.J. Respiratory metabolism: glycolysis, the TCA cycle and mitochondrial electron transport. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2004;7:254–261. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang J., Zhang T., Li Y., Li L., Wang Y., Yang B., et al. High-level expression of Thermomyces dupontii thermo-alkaline lipase in Pichia pastoris under the control of different promoters. 3 Biotech. 2019;9:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s13205-018-1531-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang X., Zhang X., Liang S., Ye Y., Lin Y. Key regulatory elements of a strong constitutive promoter, PGCW14, from Pichia pastoris. Biotechnol Lett. 2013;35:2113–2119. doi: 10.1007/s10529-013-1312-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blazeck J., Liu L., Redden H., Alper H. Tuning gene expression in Yarrowia lipolytica by a hybrid promoter approach. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:7905–7914. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05763-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fillet S., Adrio J.L. Microbial production of fatty alcohols. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;32 doi: 10.1007/s11274-016-2099-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blazeck J., Alper H.S. Promoter engineering: recent advances in controlling transcription at the most fundamental level. Biotechnol J. 2013;8:46–58. doi: 10.1002/biot.201200120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Menendez J., Valdes I., Cabrera N. The ICLI gene of Pichia pastoris, transcriptional regulation and use of its promoter. Yeast. 2003;20:1097–1108. doi: 10.1002/yea.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu B., Zhang Y., Zhang X., Yan C., Zhang Y., Xu X., et al. Discovery of a rhamnose utilization pathway and rhamnose-inducible promoters in Pichia pastoris. Sci Rep. 2016;6:1–8. doi: 10.1038/srep27352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xiong X., Chen S. Expanding toolbox for genes expression of Yarrowia lipolytica to include novel inducible, repressible, and hybrid promoters. ACS Synth Biol. 2020;9:2208–2213. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.0c00243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao Y., Liu S., Lu Z., Zhao B., Wang S., Zhang C., Xiao D., Foo J.L., Yu A. Hybrid promoter engineering strategies in Yarrowia lipolytica : isoamyl alcohol production as a test study. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2021:1–24. doi: 10.1186/s13068-021-02002-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Puseenam A., Kocharin K., Tanapongpipat S., Eurwilaichitr L., Ingsriswang S., Roongsawang N. A novel sucrose-based expression system for heterologous proteins expression in thermotolerant methylotrophic yeast Ogataea thermomethanolica. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2018;365:1–6. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fny238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Madzak C., Tréton B., Blanchin-Roland S. Strong hybrid promoters and integrative expression/secretion vectors for quasi-constitutive expression of heterologous proteins in the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2000;2:207–216. doi: 10.1038/sj.jim.2900821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nehlin J.O., Carlberg M., Ronne H. Control of yeast GAL genes by MIG1 repressor: a transcriptional cascade in the glucose response. EMBO J. 1991;10:3373–3377. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04901.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rajkumar A.S., Liu G., Bergenholm D., Arsovska D., Kristensen M., Nielsen J., et al. Engineering of synthetic, stress-responsive yeast promoters. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nevoigt E., Kohnke J., Fischer C.R., Alper H., Stahl U., Stephanopoulos G. Engineering of promoter replacement cassettes for fine-tuning of gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:5266–5273. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00530-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blazeck J., Reed B., Garg R., Gerstner R., Pan A., Agarwala V., Alper H.S. Generalizing a hybrid synthetic promoter approach in Yarrowia lipolytica. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97:3037–3052. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4421-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dulermo R., Brunel F., Dulermo T., Ledesma-Amaro R., Vion J., Trassaert M., et al. Using a vector pool containing variable-strength promoters to optimize protein production in Yarrowia lipolytica. Microb Cell Factories. 2017;16:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12934-017-0647-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data that supports the finding of this study are available in the main text and the supplementary materials.