Abstract

Purpose

To identify literature on variations and knowledge gaps in the incidence, diagnosis, and management of developmental dysplasia of hip (DDH) in India.

Methods

Following standard methodology and PRISMA-ScR guidelines, a scoping systematic review of literature on incidence, diagnosis, and treatment of DDH in India was conducted. Studies conducted in India, published in indexed or non-indexed journals between 1975 and March 2021, were included in the search.

Results

Of 57 articles which met the inclusion criteria, only 33 studies (57.8%) were PubMed-indexed. Twenty-eight studies (49%) were published in Orthopaedic journals and majority had orthopaedic surgeon as the lead author (59.6%). Sixteen studies were mainly epidemiological, 20 reported screening/diagnosis, and 21 reported treatment of DDH. Almost 90% of the studies (51) were Level 4 or 5 according to the levels of evidence in research. There is lack of clarity in the definition of hip dysplasia and screening/diagnostic guidelines to be used. The incidence of hip dysplasia in India is reported to be 0–75 per 1000 live births, with true DDH between 0 and 2.6/1000. Late-presenting DDH is common in India, with most studies reporting a mean age of > 20 months for children presenting for treatment. The treatment is also varied and there is no clear evidence-based approach to various treatment options, with lack of long-term studies.

Conclusion

This systematic scoping review highlights various knowledge gaps pertaining to DDH diagnosis and management in India. High-quality, multicentric research in identified gap areas, with long-term follow-up, is desired in future.

Keywords: Developmental dysplasia of hip, Dislocation, Screening, Ultrasonography, Treatment, Scoping review, India

Introduction

Developmental dysplasia of hip (DDH) includes a wide spectrum of presentation, from sub-clinical dysplasia to complete dislocation of the hip joint [1]. The reported incidence of DDH varies from 1 per 1000 live births to as high as 76.1/1000 in Navajo Indians, depending on the definition used as well as the region/population under consideration [2, 3].

Similar to its wide spectrum of presentation, there is a wide variation in diagnostic guidelines as well as treatment practices across the world. Universal clinical examination of newborns with selective ultrasonography (USG) screening programmes have been implemented in various developed countries for several years [4–6]. However, very limited screening programmes/guidelines are in place in developing countries of the global south. This may be affecting the actual reported incidence of DDH from these poorly served areas. Among the various risk factors of DDH, swaddling is one of most common modifiable risk factors. The practice of swaddling again is different across various geographical and cultural regions [7–9].

The treatment of DDH is guided by the age at which it is diagnosed. Mostly, treatment of DDH in a child less than 6 months old is in the form of a harness or abduction brace [10]. Closed reduction (CR) with hip spica is the typical treatment in children between 6 and 18 months of age. Children above 18 months of age or those failing closed reduction undergo open reduction (OR), along with various supplementary femoral or pelvic procedures, depending on the case [10]. However, controversy still exists regarding exact treatment methodologies and long-term outcomes.

India is the second most populous country in the world with 25 million births each year [11]. India has wide geographic and cultural variations, with a different healthcare system and resources as compared to developed countries. The primary objective of this scoping systematic review was to identify literature on variations in the incidence, diagnosis, and management of DDH in India. The secondary objective was to identify current knowledge gaps and set a platform for future studies. By identifying local variations about DDH and present knowledge gaps, this review should help in making tailored guidelines for local needs as well to guide future studies in areas where evidence is lacking.

Analysis and Methods

For this scoping systematic review, we followed a well-structured protocol based on recommendations and methodology of standard literature on the subject [12, 13]. We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist and explanations to report our findings [14]. Ethics approval was not required for this study, as it included review of openly available literature. We followed the steps in our methodology for this scoping review as described below:

Step 1: Identifying the Research Question

“What is the demography of DDH and its management practices in India?” was our primary research question. The term ‘DDH’ included the entire spectrum of hip dysplasia—from mild asymptomatic dysplasia to frank hip dislocation. The demography of DDH included, but was not limited to, the definition and incidence of DDH in India, the state or geographical area reported from, male/female ratio, risk factors considered, and age at diagnosis/presentation of DDH reported in the studies. The management of DDH included, but was not limited to, various screening and diagnostic protocols followed in India, as well as treatment strategies including conservative or surgical techniques and outcomes.

Step 2: Identifying the Relevant Studies

To scope the research question, we developed a search strategy to identify both published and unpublished studies. With an initial search of online databases (PubMed, EMBASE, SCOPUS, Directory of Open Access Journals, and CINAHL), relevant articles published in English from January 1975 till March 2021 were identified. Using various keywords used in these articles, we finalised medical subject headings (MeSH) and search terms for this study. ‘Indian literature’ was defined as studies that included individuals living in India; research conducted in India, at least in some part; and published in either Indian or non-Indian journals. After the PubMed search was completed, other databases were searched with customized search terms and Boolean operators, as necessary. To expand our search, references of identified articles were scanned for more possible studies addressing our research question. To identify relevant published/unpublished studies, case reports, editorials, expert opinions, and commentaries, we performed a grey literature search from various sources, e.g., Google Scholar, Web of Science (WoS), and ResearchGate, Finally, to sum up, a Google search was also performed using various search terms, to identify any remaining Indian studies or articles in non-indexed journals or grey literature.

Step 3: Study Selection

We included all studies pertaining to demography or management of DDH as described above in Step 1 (the research question). All study designs including qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods, reviews (narrative, systematic and scoping), case reports, and case series were included. We excluded all studies that reported on adult subjects or those reporting on syndromic, teratological, neurological and other atypical forms of DDH. For study selection, a stepwise screening process was followed. First, the title and abstract of identified studies was screened by investigator SC for inclusion criteria. Duplicates were removed and full texts of the selected studies were screened for inclusion/exclusion criteria. Any controversy on inclusion/exclusion of a particular study was resolved by meeting and discussion with the senior author (AA).

Step 4: Charting the Data

We made a spreadsheet on Microsoft Excel with variables extracted, to answer the research question and chart the data from included studies.

Step 5: Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting Results

From the charted data, the authors analyzed and summarized the results to provide an overview of literature available on DDH in India. Controversies and knowledge gaps were highlighted and discussed. The level of evidence of included studies was determined [15] and the methodological quality was assessed using Methodological Index for Non-randomized Studies (MINORS) [16]. Two authors (SC and AA) scored the articles independently and mean score was assessed for quality. The quality was categorized as follows: a score of 0–8 was considered poor quality, 9–12 was considered fair quality, and 13–16 was considered excellent quality for non-comparative studies [16]. Case reports, abstracts, and narrative review articles were automatically judged to be at high risk of bias.

Results

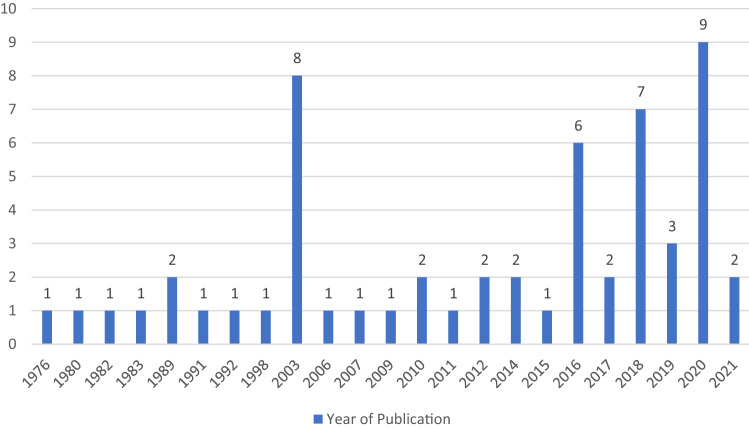

A total of 121 studies were identified through database searching, hand searching, and additional sources. After removing the duplicates and excluding reports that did not meet the inclusion criteria, 57 articles met the criteria for final data extraction and analysis (Fig. 1). We analyzed the indexing of journals of studies included in this scoping review. Only 33 studies (57.8%) were published in PubMed-indexed literature [9, 17–48], while the rest of the studies (42.2%) were in other indexed or non-indexed literature [49–72] (Fig. 2). Among these, at least 7 publications were in predatory journals [56, 60, 62–64, 69, 70, 73]. Twenty-eight studies were published in Orthopaedic journals, 13 studies were published in Pediatric journals, and the remaining 16 were in other journals. While considering the specialty of the lead author of included studies, 59.64% (34) were Orthopaedic surgeons, Paediatrician was the lead author in 15.7% (9), Radiologist in 10.5% (6), and other profession in 14% (8). When we looked at the state-wise distribution of research conducted, we found that almost 55% (31) articles were from four states/union territories (UTs): Maharashtra with 11, Delhi with 8, and Karnataka and Tamil Nadu with six studies each. Mumbai and Delhi, the two largest metro cities in India, had one-third (33.3%) of all research published.

Fig. 1.

The search process with PRISMA-ScR flow diagram

Fig. 2.

Journal indexing and subject, lead author profession, and study type

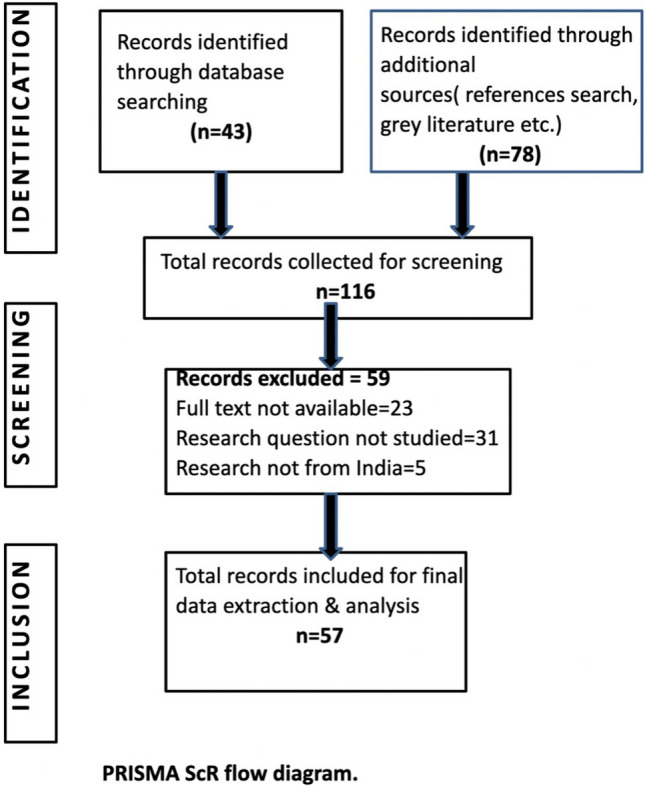

Sixteen epidemiological studies reported the incidence/prevalence of hip dysplasia and other congenital anomalies. Twenty articles reported screening and/or diagnosis aspect of DDH, while treatment of DDH (CR/OR) was the main focus of study in 21 articles. Year-wise publication trends are shown in Fig. 3. 84% (48) of articles were published after the year 2000 onwards. Two publication peaks were noted in 2003 and 2020, since special issues dedicated to DDH were published in those years. Almost 90% of the studies (n = 51) were level 4 or 5, according of the Levels of Evidence in research (Fig. 4). There was no level 1 study. The mean MINORS score of eligible articles was 6.9/16 (range 3–11). 29 articles had poor, 9 had fair, and none had excellent methodological quality. The major limitations noted in the methodology of the selected studies were lack of prospective sample size, power of study and statistical significance, lack of blinded/unbiased assessment of study endpoint, and limited follow-up to assess endpoints and possible adverse outcomes.

Fig. 3.

Publication trends over the years

Fig. 4.

Level of evidence of included studies

Detailed Analysis of the Included Articles

The findings are presented together, along with the gaps identified regarding major aspects of the research on DDH.

Definition of Hip Dysplasia and CDH/DDH/Hip Instability

Hip dysplasia is a condition with a wide spectrum, ranging from mild dysplasia to frank dislocation of the hip. There is lack of clarity on the precise definition of hip dysplasia, especially in older studies prior to 1990, which used the older terminology CDH (Congenital Dislocation of Hip) [17, 30, 31, 38]. Gupta et al. [18] used the term Neonatal Hip Instability (NHI) to include the full spectrum of hip dysplasia in newborns. A single study used the term ‘neglected CDH’, to represent frank dislocations presenting late for treatment [19]. A few studies described the term DDH along with Graf’s ultrasound classification to include the whole spectrum of hip dysplasia [22, 27, 74]. Most of the newer studies have used the term DDH for frank hip dislocations presenting for treatment, confirmed with clinical exam and radiographs [20, 23–25, 35, 46–48, 51, 52, 63, 64, 68].

Screening and Diagnostic Tools

Many studies describe the use of only clinical examination for screening/diagnosis of hip dysplasia [17, 30–32, 36, 38, 45, 54, 70]. These studies report the use of Barlow/Ortolani tests, asymmetry of thigh/gluteal folds, and limb length discrepancy as clinical tools for screening. A few other studies report the use of ultrasound or radiographs as adjuncts to clinical examination [18, 22, 23, 27, 40, 52, 56, 59, 60, 62, 69]. In a review article, the authors reported the clear advantage of USG over X-ray in unossified femoral head, with the option of dynamic evaluation [26]. Interestingly, in a survey of screening practices of Orthopaedic surgeons in India, clinical examination was favoured by 82.7% surgeons as a screening tool for DDH [29]. Ultrasound was used as a screening tool by only 55% of the respondents and 66% were likely to advise X-ray for confirming the diagnosis of DDH after the age of 3 months [29].

There is a marked variability in the timing of DDH screening reported by various studies, demonstrating a lack of consensus in this important aspect. Few studies have reported their results based on a one-time examination, either within 24–48 h after birth [54, 71], at 6 weeks of age [22, 60], or within the first 3 months of life [17, 59]. Other studies reported their findings based on more than one screening examination at varying schedules—at birth, within 24 h, at discharge [31]; within 24 h and 2 weeks after first exam [18]; first 48 h, additional 6 and 12 weeks for selected cases [27]; and 2 days, 2 weeks, and 2 months, with additional screen at 6 months for unstable hips [56]. Bhalvani et al. utilised first DPT vaccination visit at 6 weeks for hip screening [22]. In the survey by Hooper et al., 84.4% of the respondents were of the opinion of performing screening at each well-baby clinic, at least till the age of 6 months [29].

Demography (Incidence and Age at Diagnosis)

Of the many epidemiological studies reporting on the entire spectrum of congenital malformations in newborns and infants in various parts of India [17, 18, 30–34, 36–39, 44, 45, 54, 70, 71], only four studies reported on the incidence of DDH in their study results [27, 30, 31, 38]. Only a few studies looked specifically at the incidence of musculoskeletal anomalies, including DDH, in newborns [17, 18, 22, 45, 54, 70, 71]. The reported incidence of hip dysplasia/DDH is quite variable in India, ranging from 0 to almost 75 per thousand, depending upon the type of study and the definition of DDH used (Table 1). All are institution-based studies, except one, which reported the incidence from 15 randomly selected villages out of 94 in Haryana state [30]. There are no population-based studies on the incidence of DDH in India. One study noted that almost 86% of NHI at birth gets normalised at 6 week examination without treatment [18], while another reported very high incidence of sonographically abnormal hips but only a single true hip dislocation among 1000 participants [22]. Only three studies had participants > 10,000 [27, 38, 70]. All the studies reporting incidence/prevalence had combined participants’ number of 69,014 (Table 2).

Table 1.

Studies reporting incidence/prevalence of DDH

| S. no. | Study | Year | Area/state | Number of participants | Number of DDH | DDH incidence (per thousand) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kaushal et al. [17] | 1976 | Chandigarh | 2500 | 23 | 9.2 |

| 2 | Singh et al. [31] | 1980 | Delhi | 7274 | 7 | 1.1 |

| 3 | Kulshreshtha et al. [30] | 1983 | Ballabhgarh, Haryana | 2409 | 1 | 0.4 |

| 4 | Gupta et al. [18] | 1992 | Delhi | 6029 | 113 (20 on 2nd exam) | 18.7 (NHI) (2.6 on second examination) |

| 5 | Bhat et al. [38] | 1998 | Pondicherry | 12,337 | 4 | 0.32 |

| 6 | Gupta et al. [71] | 2003 | Jammu | 2000 | 5 | 2.5 |

| 7 | Bhalvani et al. [22] | 2011 | Vellore, Tamil Nadu | 1000 | 75 abnormal USG (1 true dislocation) | 75 (1 true clinical DDH) |

| 8 | Kumar et al. [27] | 2016 | Bangalore, Karnataka | 23,925 | 20 | 0.83 |

| 9 | Sahu et al. [54] | 2017 | Bhubaneshwar, Odisha | 1414 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | Kumari et al. [70] | 2018 | Bareilly, Uttar Pradesh | 10,126 | 10 | 0.99 (birth prevalence) |

| 11 | Barik et al. [45] | 2021 | Rishikesh, Uttarakhand | Birth prevalence calculated with CBR = 2.21/1000, 2011 census for Uttarakhand state | 32 | 1.43 per 10,000 (birth prevalence) |

NHI Neonatal hip instability, CBR Crude birth rate

Table 2.

Studies reporting treatment of late presenting DDH

| No. | Study [References] | No. of patients (hips) | Mean age (range) in months | Mean Follow up (range) in months | Surgical Protocol | Surgical procedure done | Outcome measures used | Final outcome | MINORS score/(LOE) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Only OR | OR + AO | OR + FO | OR + FO + AO | |||||||||

| 1 | Mootha et al. [20] | 15 (15) | 23.9 (12–48) | 21.2 (Min. 18) |

Anterior approach Test of stability used intra-op Post-op: 6 weeks spica + 6 weeks brace |

0 | 12 = OR + Salter | 0 | 3 = OR + FSO + Salter |

Clinical evaluation with McKay’s criteria Acetabular index on X-ray |

McKay: Excellent = 8, Good = 7 | 10 (4) |

| 2 | Bhuyan et al. [24] | 25 (30) | 46.8 (19–96) | 48 (24–91) |

a. One-stage triple procedure OR + FDRO + Salter b. Post-op: 6 weeks spica + 4 weeks abduction splint |

0 | 0 | 0 | 30 = OR + FSDRO + Salter |

Clinical stability AI on X-ray McKay’s criteria Severin & Bucholz |

McKay: Excellent = 13, Good = 14, Fair = 2, Poor = 1 |

5 (4) |

| 3 | Narasimhan et al. [25] | 35 (35) | (18–24) | (24–84) |

Standard anterior approach Intra-op ‘Test of stability’ used 6 + 6 weeks spica, No Bracing |

26 | 9 (Dega) | 0 | 0 |

Clinical stability Residual acetabular dysplasia (RAD) |

No re-dislocation. 7 cases with RAD (only OR group)—advised for acetabuloplasty | 7 (4) |

| 4 | Bhaskar et al. [28] | 55 (60) | 16 (6–36) | 28 (24–36) |

In OR Group: 4 hips = Medial approach Remaining 24 hips = Anterior approach Intra-op stability to decide FO/AO 6 + 6 weeks spica, No Brace |

28 | 5 (Salter) | 10 (FDRO / FSO) | - |

Clinical AI, Tonnis, Bucholz on X-ray MacKay’s for function |

McKay: Excellent = 36, Good = 11, Fair = 4. Re-dislocations = 5 hips | 10 (4) |

| 5 | Jagadesh et al. [68] | 21 (21) | 66.8 (25–96) | 15.1 |

Lateral approach used for OR 3 months of spica No Brace |

0 | 9 (Pemberton) | 0 | 12 (5 = OR + VDRO + Pemberton) (7 = OR + FS + VDRO + Pemberton) |

Clinical & radiographs AI, CEA, Tonnis, Severin classification on X-ray McKay’s for functional outcome |

McKay: Excellent = 8, Good = 11, Fair = 1, Poor = 1 Re-dislocation = 1 | 10 (4) |

| 6 | Manimaran et al. [64] | 10 (12) | 84 (36–180) | 44.4 (30–60) |

One-stage procedure: OR + VDRO + FSO + Dega/Salter Anterior approach Hip spica = 6–8 weeks No brace |

0 | 0 | 0 | 12 = OR + VDRO + Pelvic Osteotomy (Salter = 6, Dega = 6) |

Clinical AI on X-rays and Mckay’s criteria used |

McKay: Excellent = 3, Good = 2, Fair = 5, Poor = 2 Re-dislocation = 1 | 10 (4) |

| 7 | Tej et al. [63] | 34 (41) | 34.7 | 36 (13–65) |

Anterior approach 3 month hip spica Brace case to case basis |

15 | 16 (Pemberton) | 0 | 10 (3 = OR + VDRO + Pemberton) (7 = OR + VDRO + FSO + Pemberton) | AVN rate as per Kalamchi classification at mean follow-up of 3 year (44% AVN rate noted) |

AVN as per Kalamchi: No AVN = 23, Type 1 = 12, Type 2 = 3, Type 3 = 3 |

9 (4) |

OR open reduction, FDRO femoral derotation osteotomy, FO femoral osteotomy, FSO femoral shortening osteotomy, VDRO varus derotation osteotomy, FSDRO femoral shortening derotation osteotomy, AO acetabular osteotomy, AVN avascular necrosis, LOE level of evidence, AI acetabular index, CEA center edge angle

This scoping review suggests that walking age presentation/late-detected DDH is common in India. One study had a mean age of 16 months at the time of treatment [28]. All other studies describing treatment of DDH had an even higher mean age of > 20 months (range 6 weeks to 9.3 years) [20, 21, 24, 63, 64, 68, 72]. In one study, 47% of children (19/44) treated for DDH at a single institution over a 3-year period presented after 1 year of age [35]. In a survey of orthopedic surgeons from India, the largest chunk of DDH patients were in the 1–5 year age group [29].

Management

Treatment Provided in Infancy

There is no consensus on the management of DDH in infancy and various kinds of braces/splints were used by different authors. These include Palmen’s abduction splint [17], Frejka splint [18], von Rosen splint [18], Pavlik harness [27, 41, 58], and hip spica [18, 41]. Khan et al. reported using Pavlik harness with ultrasound-based monitoring to follow the treatment [58]. None of the studies describe long-term outcomes, failures, or complications of brace treatment during infancy. Double/triple diaper application has been described to give false sense of treatment and has no benefit [43].

Treatment in Late-Presenting Cases

There is a lack of studies to draw consensus or evidence regarding criteria for selecting closed reduction (CR) or open reduction (OR). Similarly, there is no consensus on the need for femoral derotation/varus and pelvic osteotomies required (Table 2). Our scoping review found only seven studies in the Indian literature published over the past 10 years (2010–2020) that reported on the results of treatment of late-presenting DDH (after the age of 1 year). All are retrospective case series (Level IV evidence) having a small number of patients (range 10–55) and short-term follow-up of 30.9 months (range 18–91). Most authors used the classical anterior approach of open reduction of hip, though the medial approach and lateral approach for OR were reported in a couple of studies [28, 68]. Johari et al. suggest reserving the medial approach for children < 9 months of age [47]. Regarding the need for concomitant femoral osteotomy, one study reported that, based on pre-operative MRI findings, none of their cases required derotation [20]. In contrast, another study reported using femoral derotation osteotomy in all cases [24]. A review article discusses the role of pre-op traction in management of DDH [48], with no scientific evidence for or against use of it. Also, none of the articles addresses the utility of routine post-operative CT scan or MRI after CR/OR. The Dega [64, 72], Salter [21, 24, 28, 64], and Pemberton osteotomies [63, 68] are described as options for pelvic procedure with no clear evidence behind choices.

Outcomes of Treatment

All the studies report very short-to-mid-term follow-up (range of follow-up: 15 months to 7.5 years). None of the studies report long-term outcomes at skeletal maturity or adulthood. Outcomes were reported using clinical parameters such as modified McKay’s criteria and radiological parameters such as Severin’s classification & acetabular index on X-ray. The Bucholz or Kalamchi & MacEwen classifications were used to report avascular necrosis (AVN). One study reported 10% re-dislocation [28], while a few other studies reported no re-dislocation on follow-up [17, 20, 24, 64]. One study reported 44% AVN after single-stage surgery in walking age DDH [63], with a trend for higher rates in older children, high Tönnis grades & those requiring pelvic procedure. Narasimhan et al. reported that 20% of cases required secondary procedures for residual acetabular dysplasia (RAD) at 18 month follow-up [25]. One study reported no significant correlation between radiological parameters and functional outcome [20].

Complications and Management of Failures/Re-dislocations

Most of the studies reported re-dislocation and AVN among complications noticed at short-term follow-up after CR/OR. Migration of trans-articular pin could be a catastrophic complication with use of trans-articular pin after OR [43] and one study reported a case of intra-abdominal migration of K-wire from hip [19]. “Long leg dysplasia” was described in some cases undergoing open reduction and femoral osteotomy [43]. Johari et al. [47] discussed various causes of failure in primary surgery of DDH and divided them into three categories: immediate, delayed, and late failures. They emphasised that revision surgeries require a great amount of expertise and should only be attempted by experts in the field.

Discussion

This scoping systematic review aimed to identify variations in the incidence, diagnosis, and management of DDH in India. Considering the fact that one-sixth of the world’s population resides in India, this scoping systematic review highlights a distinct lack of sufficient literature and quality research on various aspects of DDH in India. Almost 30% (20) of the studies included in this review were in non-indexed online journals, including predatory journals and grey literature, and 90% of the studies were Level 4 or 5 evidence. We noted a trend of recent increase in publications, with 48 (84%) publications after the year 2000. Almost one-third of the studies were from Mumbai and Delhi, probably because these metro cities have many tertiary-care centres where cases are referred for further treatment, especially for conditions like DDH which require specialty care. With such a large population in India distributed across 28 states and 8 union territories, 55% of studies were limited to only four states/UTs (Maharashtra, Delhi, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu). This may not be representative of the actual epidemiology and treatment outcomes of DDH in the entire country.

Our scoping review revealed that the reported incidence of DDH in India varies between 0 and 75 per 1000 live births. However, as expected, there are varied definitions, screening methods, and timing of screening used to define this incidence in India. The incidence of 9.2 per thousand in the study by Kaushal et al. [17] was based on early clinical examination at a mean age of 3.6 days. Similarly, Gupta et al. [18] reported high incidence of NHI (18.7/1000 live births) on the first clinical exam, but it came down to 2.6/1000 on subsequent examinations. Bhalvani et al. [22] reported very high incidence (75/1000 live births) of sonographically abnormal hips, but only 1/1000 true dislocations. If we summarize the literature available, the true DDH incidence in India is perhaps between 0 and 2.6 per thousand. However, none of these studies may be depicting a true representation of the wide geographic and cultural variations of the entire spectrum of DDH in the second most populous country of the world. Larger population-based studies and from multiple centres across India are desired in future to address this knowledge gap.

Standard DDH care pathways utilize a combination of well-timed clinical examinations with judicious use of radiological (USG or X-rays) tests along with consideration of various DDH risk factors, if any [4–6]. In this scoping review, we found many studies described the use of only clinical examination for screening/diagnosis of hip dysplasia [17, 30–32, 37, 38, 54]. Most of these studies are from the period between 1950 and 80s, when the incidence was determined based on the detection of unstable hips on neonatal physical exam plus the addition of late-diagnosed patients [75]. A few other studies conducted to identify the incidence of musculoskeletal anomalies in newborns neither defined DDH nor was any special attempt or protocol used to identify it from among various other more obvious congenital anomalies [32–34, 36, 37, 39]. To address such issues, Suresh et al. raised the need for a national birth defects registry to serve as a surveillance mechanism [76]. They suggested developing a descriptive registry with well-defined methodology, case definition, and coding of anomalies.

All of the articles published before year 2000 were primarily focused on the epidemiology of DDH and other congenital birth defects. Surprisingly, only 12 studies (21%) had a paediatrician in the research team as the lead or contributing author. Similarly, a single study (review article) was found with nursing staff as the lead author. This could be because of the lack of an established national screening programme as well as lack of awareness among general pediatricians and nurses about DDH. Pediatricians and nurses form strong pillars for any screening programme to detect childhood issues, and DDH is no different. We hope in the coming years, with greater awareness about DDH, more streams will work in collaboration with Orthopaedic surgeons to better address this issue.

Many developed countries are following DDH screening programmes and have DDH care pathways in place since several years [4–6]. However, no such national- or state-level guidelines for DDH are available in India. DDH is among nine birth defects to be screened under the Rashtriya Bal Swashtya Karyakram (RBSK), which covers 30 selected health conditions for screening, early detection, and free management [77], launched under the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India in 2013. However, it is uncertain how many children are actually screened for DDH through this initiative, considering the poor reach of social programmes and the dual public–private healthcare system prevalent in India. Since DDH is not a visible external birth defect, without specific training for DDH screening, it may be difficult to be picked up by auxiliary and community healthcare workers. Also, the RBSK programme does not provide an actual protocol for DDH screening, use of imaging (USG/ X-ray), and/or specific guidelines for referral and treatment. Our scoping review did not find any reported robust DDH screening programme/guidelines being practiced at any institution in India. However, we expect that many institutions or paediatric orthopaedic units in India must be following a local protocol for the same. When queried about presence of DDH care guidelines at their institute in a survey of orthopedists from India, only about one-third of respondents answered in the affirmative [29]. In the same survey, 56% orthopedic surgeons felt that there was under-referral of at-risk or suspected cases and 91.9% supported the development of a national DDH care pathway for India.

If we look at the treatment practices of DDH in India, there is a scarcity of literature describing the treatment of DDH in infancy. A few studies describe the use of various braces including Pavlik harness [18, 41, 58]. However, good-quality studies describing the use of bracing in infancy and its long-term follow-up results are lacking. Only a few studies (seven articles over the past 10 years) report on the treatment outcomes of late-presenting DDH, which should have been an important focus for high-quality research in our country considering the older age of presentation. Most of the published studies had patients presenting after walking, at a mean age of > 20 months [20, 21, 24, 25, 63, 64, 68, 72]. Apart from lack of awareness and lack of access to healthcare, the lack of a proper screening programme may be a reason for late detection of DDH in India [35]. Unfortunately, most studies reporting on treatment outcomes of late-presenting DDH include only a small number of patients and over a short period of follow-up. There is a paucity of studies showing results up to skeletal maturity, and larger studies with longer follow-up are desired to draw a proper conclusion.

A potential limitation of this scoping review might be non-inclusion of older, print-only editions, which could be a factor for the apparently rising publication trend noted in the past 2 decades. Similarly, a few articles in grey literature or non-indexed journals might have been missed despite extensive search.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this scoping review highlights knowledge gaps in various aspects of DDH management in India. Right from lack of an established national DDH care pathway, to lack of enough quality studies regarding demography of DDH in India and to treatment approaches with long-term outcomes, this scoping review points out the need for more well-conducted studies. Further studies are needed to know the incidence of DDH and practice variability for its diagnosis and treatment in Indian perspective. We hope that these areas will be a topic of interest for future research in India.

Author Contributions

SC and AA conceptualised and designed the study. Data analysis and review was carried out by SC and AA. The first draft of the manuscript was written by SC and edited by AA, RP, and ANJ. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors state that they have no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise, concerning the material or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper.

Ethical Standard Statement

Since this is a scoping systematic review, ethics approval to participate were not required for this study.

Informed Consent

Since this is a scoping systematic review, consent to participate were not required for this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Suresh Chand, Email: sureshdocucms@gmail.com.

Alaric Aroojis, Email: aaroojis@gmail.com.

Ritesh A. Pandey, Email: riteshpandey8262@yahoo.com

Ashok N. Johari, Email: drashokjohai@hotmail.com

References

- 1.What is Hip Dysplasia?—International Hip Dysplasia Institute. Retrieved July 20, 2021, from https://hipdysplasia.org/developmental-dysplasia-of-the-hip

- 2.Loder RT, Skopelja EN. The epidemiology and demographics of hip dysplasia. ISRN Orthopedics. 2011;2011:1–46. doi: 10.5402/2011/238607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herring JA. Tachdjians pediatric orthopaedics. 6. New York: Elsevier; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaw BA, Segal LS. Evaluation and referral for developmental dysplasia of the hip in infants. Pediatrics. 2016 doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mulpuri K, Song KM. AAOS Clinical Practice Guideline: Detection and nonoperative management of pediatric developmental dysplasia of the hip in infants up to six months of age. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2015;23(3):206–7. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-15-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Developmental dysplasia of the hip—NHS. Retrieved July, 20, 2021, from https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/developmental-dysplasia-of-the-hip

- 7.Lipton EL, Steinschneider A, Richmond JB. Swaddling, a childcare practice: Historical, cultural and experimental observations. Pediatrics. 1965;35(SUPPL):519–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rabin DL, Barnett CR, Arnold WD, Freiberger RH, Brooks G. Untreated congenital hip disease. A study of the epidemiology, natural history and social aspects of disease in Navajo population. American Journal of Public Health and the Nation's Health. 1965;55(Suppl 2):1–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pinto DA, Aroojis A, Mehta R. Swaddling practices in an Indian institution: are they hip-safe? a survey of paediatricians, nurses and caregivers. Indian Journal of Orthopaedics. 2020;55(1):147–157. doi: 10.1007/s43465-020-00188-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Essa RS, Aljahdali FH, Alkhilaiwi RM, Philip W, Jawadi AH, Khoshhal KI. Diagnosis and treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip: A current practice of paediatric orthopaedic surgeons. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery (Hong Kong) 2017 doi: 10.1177/2309499017717197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Census of India Website: Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Retrieved July 20, 2021, from https://censusindia.gov.in/2011-Common/CensusInfo.html

- 12.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science. 2010;5:69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin w, O’Brian KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D,, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2018;169(7):467–73. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine: Levels of Evidence (March 2009)—Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM), University of Oxford. Retrieved July 20, 2021, from https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/oxford-centre-for-evidence-based-medicine-levels-of-evidence-march-2009

- 16.Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): Development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ Journal of Surgery. 2003;73(9):712–716. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-2197.2003.02748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaushal V, Kaushal S, Bhakoo O. Congenital dysplasia of the hip in northern India. International Surgery. 1976;61:29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta AK, Kumari S, Arora PL, Kumar R, Mehtani AK, Sood LK. Hip instability in newborns in an urban community. National Medical Journal of India. 1992;5(6):269–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marya KM, Yadav V. Unusual K-wire migration. Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 2006;73(12):1107–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02763056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mootha AK, Saini R, Dhillon M, Aggarwal S, Wardak E, Kumar V. Do we need femoral derotation osteotomy in DDH of early walking age group? A clinico-radiological correlation study. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery. 2010;130(7):853–8. doi: 10.1007/s00402-009-1020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mootha A, Saini R, Dhillon M, Aggarwal S, Kumar V, Tripathy S. MRI evaluation of femoral and acetabular anteversion in developmental dysplasia of the hip: A study in an early walking age group. Acta Orthopaedica Belgica. 2010;76(2):174–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhalvani C, Madhuri V. Ultrasound profile of hips of south Indian infants. Indian Pediatrics. 2011;48(6):475–477. doi: 10.1007/s13312-011-0075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agarwal A, Gupta N. Risk factors and diagnosis of developmental dysplasia of hip in children. Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma. 2012;3(1):10–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhuyan BK. Outcome of one-stage treatment of developmental dysplasia of hip in older children. Indian Journal of Orthopaedics. 2012;46(5):548–55. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.101035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Narasimhan R, Patil M, Mahna M. Outcome of surgical management of developmental dysplasia of hip in children between 18 and 24 months. Indian Journal of Orthopaedics. 2014;48(5):458–462. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.139841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karnik AS, Karnik A, Joshi A. Ultrasound examination of pediatric musculoskeletal diseases and neonatal spine. Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 2016;83(6):565–77. doi: 10.1007/s12098-015-1957-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar RK, Shah P, Ramya AN, Rajan R. Diagnosing developmental dysplasia of hip in newborns using clinical screen and ultrasound of hips—An Indian experience. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics. 2016;62(3):241–5. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmv107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhaskar A, Desai H, Jain G. Risk factors for early re-dislocation after primary treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip: Is there a protective influence of the ossific nucleus? Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 2016;50(5):479–485. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.189610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hooper N, Aroojis A, Narasimhan R, Schaeffer EK, Habib E, Wu JK, et al. Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip: An examination of care practices of orthopaedic surgeons in India. Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 2020;55(1):158–168. doi: 10.1007/s43465-020-00233-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kulshreshtha R, Nath LM, Upadhyay P. Congenital malformations in live born infants in a rural community. Indian Pediatrics. 1983;20(1):45–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh M, Sharma N. Spectrum of congenital malformations in the newborn. Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 1980;47(386):239–44. doi: 10.1007/BF02758201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chaturvedi P, Banerjee K. Spectrum of congenital malformations in the newborns from rural Maharashtra. Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 1989;56(4):501–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02722424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhide P, Kar A. A national estimate of the birth prevalence of congenital anomalies in India: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pediatrics. 2018;18(1):175. doi: 10.1186/s12887-018-1149-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agrawal D, Biswa BM, Sarangi R, Kumar S, Mahapatra SK, Chinara PK. Study of incidence and prevalence of musculoskeletal anomalies in a tertiary care hospital of eastern India. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 2014 doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/7882.4380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rebello G, Joseph B. Developmental dysplasia of the hip in children from southwest India—Will screening help? Indian Journal of Orthopaedics. 2003;37(4):210–214. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choudhury AR, Mukherjee M, Sharma A, Talukder G, Ghosh PK. Study of 1,26,266 consecutive births for major congenital defects. Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 1989;56(4):493–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02722422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verma M, Chhatwai J, Singh D. Congenital malformations—A Retrospective study of 10,000 cases. Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 1991;58(2):245–52. doi: 10.1007/BF02751129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bhat BV, Babu L. Congenital malformations at birth—A prospective study from south India. Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 1998;65(6):873–81. doi: 10.1007/BF02831352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baruah J, Kusre G, Bora R. Pattern of gross congenital malformations in a tertiary referral hospital in northeast India. Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 2015;82(10):917–22. doi: 10.1007/s12098-014-1685-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pandey RA, Johari AN. Screening of newborns and infants for developmental dysplasia of the hip: A systematic review. Indian Journal of Orthopaedics. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s43465-021-00409-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sriram K. Developmental dysplasia of the hip: Management under six months of age. Indian Journal of Orthopaedics. 2003;37(4):223–226. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Joseph B. Editorial: Developmental dysplasia of hip. Indian Journal of Orthopaedics. 2003;37(4):209–210. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Narsimhan R. Complications of management of developmental dysplasia of the hip. Indian Journal of Orthopaedics. 2003;37(4):237–240. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chinara PK, Singh S. East-West differentials in congenital malformations in India. Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 1982;49(398):325–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02834415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barik S, Pandita N, Paul S, Kumari O, Singh V. Prevalence of congenital limb defects in Uttarakhand state in India—A hospital-based retrospective cross-sectional study. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health. 2021;9:99–103. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johari AN. The role of hip arthrography in developmental dysplasia of the hip. Indian Journal of Orthopaedics. 2003;37(4):244–246. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johari AN, Wadia FD. Revision surgery for developmental dysplasia of the hip. Indian Journal of Orthopaedics. 2003;37(4):233–236. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bhatia M, Joseph B. Is routine pre-reduction traction necessary for children with developmental dysplasia of the hip? Indian Journal of Orthopaedics. 2003;37(4):241–243. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bhaskar A, Kansara P. A review of “capture rate’’ between physicians and care-giver suspicion leading to diagnoses of late-presenting DDH: A single centre perspective. International Journal of Paediatric Orthopaedics. 2020;6(2):7–11. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chauhan H. Can we predict the need for secondary procedures in walking DDH? International Journal of Paediatric Orthopaedics. 2020;6(2):53–58. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Singh V, Yasam R, Garg V, Barik S. Re-dislocation after primary open reduction in DDH-management and early results. International Journal of Paediatric Orthopaedics. 2020;6(2):48–52. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pasupathy B, Sathish M. Reliability of a new radiographic classification for developmental dysplasia of the hip. International Journal of Paediatric Orthopaedics. 2020;6(1):16–19. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Behera P. Role of proximal femoral osteotomy in the management of developmental dysplasia of hip. International Journal of Paediatric Orthopaedics. 2020;6(2):27–32. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sahu S, Nayak MK, Mohapatra I, Biswal SR, Jha A. Burden of developmental dysplasia of hip among neonates in a tertiary care setting of Odisha. Indian Journal of Orthopaedics Surgery. 2017;13:346–349. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jain RK, Patel S. Developmental dysplasia of hip—An overview. International Journal of Orthopaedics Science. 2017;3(4):42–49. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Raj B, Menon G, Jeynath PV, Sai PMV. Developmental dysplasia of hip—Sonographic findings. International Journal of Recent Trends in Science and Technology. 2016;18(2):354–357. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ilangovan, G., Kumar, L., Balaganesan, H. 2020. Imaging of Developmental Dysplasia of Hip—Hips don’t lie, but it hurts and then I cry. https://epos.myesr.org/poster/esr/ecr2020/C-029032020

- 58.Khan MJ, Abbas M, Ali SM, Khalid M, Mehtab A. Role of ultrasound in management of developmental dysplasia of hip with Pavlik harness. Journal of Bone and Joint Diseases. 2018;33(2):42–46. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kale D, Salunkhe A, Parekh H, Joshi S, Prasanth A. Role of Ultrasonography in early diagnosis and management of infant hip dysplasia. Journal of Orthopaedics. 2007;4(2):33. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rajput, S. S., & Yadav, R. S. (2016). Observational study to find association between congenital talipes equinovarus and developmental dysplasia of the hip and role of ultrasound screening. Global Journal of Research Analysis, 5(10).

- 61.Sherwani P, Vire A, Anand R, Aggarwal A. Utility of MR imaging in developmental dysplasia of hip. Austin Journal of Radiology. 2016;3(3):1052. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Patel N, Sharma A, Patel M, Rathod Y. Role of ultrasound in developmental dysplasia of the hip in Infants. International Journal of Scientific Research. 2019;8(4):28–31. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tej BY, Shetty BC, Hegde AH. Evaluation of avascular necrosis during midterm follow up in DDH cases treated by single stage surgery in the walking age group. Journal of Critical Reviews. 2020;7(14):4251–4259. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Manimaran KP, Sathish M, Govardhan RH. Outcome analysis of management of untreated Developmental dysplasia of hip by klisic procedure. IOSR- Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences. 2019;18(2):38–44. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bhatnagar N. Pediatric musculoskeletal ultrasound. Indian Journal of Rheumatology. 2018;13(5):57–64. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kumari P, Rani M. Developmental dysplasia of the hip. Orthopedics and Rheumatology Open Access. 2018;10(4):555794. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Uppin RB, Saidapur SK, Mittal AR, Kumar U. Radiological and functional outcome of management of bilateral congenital dislocation of hip in a 1 year old infant: A case report. Journal of Orthopaedic Education. 2019 doi: 10.21088/joe.2454.7956.5219.6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jagadesh G, Venugopal SM, Chaitanya SSRK, B, Karthik Gudaru. Outcome of surgical management of late presenting developmental dysplasia of hip with pelvic and femoral osteotomies. Indian Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery. 2018;4(1):53–59. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Priyadarshi A, Gupta KL. Role of clinical examination As screening tool for detection of developmental dysplasia of hip in Infants. Indian Journal of Applied Research. 2018;8(2):52–53. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kumari O, Singh V. Prevalence and pattern of congenital musculoskeletal anomalies: A single centre study. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 2018;12(1):16–19. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gupta RK, Gupta CR, Singh D. Incidence of congenital malformations of the musculo-skeletal system in new live borns in Jammu. JK Science. 2003;5(4):157–160. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Narasimhan R. Dega pelvic osteotomy in the management of developmental dislocation of hips in older children. Apollo Medicine. 2009;6(1):32–39. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shen C, Björk B-C. ‘Predatory’ open access: a longitudinal study of article volumes and market characteristics. BMC Medicine. 2015;13:230. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0469-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Graf R. Hip sonography: background; technique and common mistakes; results; debate and politics; challenges. Hip Int. 2017;27(3):215–219. doi: 10.5301/hipint.5000514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bialik V, Bialik GM, Blazer S, Sujov P, Wiener F, Berant M. Developmental dysplasia of the hip: a new approach to incidence. Pediatrics. 1999;103(1):93–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Suresh S, Thangavel G, Sujatha J, Indrani S. Methodological issues in setting up a surveillance system for birth defects in India. National Medical Journal of India. 2005;18(5):259–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rashtriya Bal Swasthya Karyakram (RBSK): National Health Mission. Retrieved July 20, 2021, from https://www.nhm.gov.in/index1.php?lang=1&level=4&sublinkid=1190&lid=583