Abstract

OBJECTIVES

With development of antegrade cerebral perfusion, the necessity of deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (CA) in aortic arch surgery has been called into question. To minimize the adverse effects of hypothermia, surgeons now perform these procedures closer to normothermia. This study examined postoperative outcomes of hemiarch replacement patients using unilateral selective antegrade cerebral perfusion and mild hypothermic CA.

METHODS

Single-centre retrospective review of 66 patients undergoing hemiarch replacement with mild hypothermic CA (32°C) and unilateral selective antegrade cerebral perfusion between 2011 and 2018. Antegrade cerebral perfusion was delivered using right axillary artery cannulation. Postoperative data included death, neurological dysfunction, acute kidney injury and renal failure requiring new dialysis. Additional intraoperative metabolic data and blood transfusions were obtained.

RESULTS

Eighty-six percent of patients underwent elective surgery. Mean age was 67 ± 3 years. Lowest mean core body temperature was 32 ± 2°C. Average CA was 17 ± 5 min. No intraoperative or 30-day mortality occurred. Survival was 97% at 1 year, 91% at 3 years and 88% at 5 years. Permanent and temporary neurological dysfunction occurred in 1 (2%) and 2 (3%) patients, respectively. Only 3 (5%) patients suffered postoperative stage 3 acute kidney injury requiring new dialysis. Intraoperative transfusions occurred in 44% of patients and no major metabolic derangements were observed.

CONCLUSIONS

In patients undergoing hemiarch surgery, mild hypothermia (32°C) with unilateral selective antegrade cerebral perfusion via right axillary cannulation is associated with low mortality and morbidity, offering adequate neurological and renal protection. These findings require validation in larger, prospective clinical trials.

Keywords: Mild hypothermia, Hemiarch replacement, Antegrade cerebral perfusion, Neurological dysfunction, Acute kidney injury

INTRODUCTION

Aortic arch surgery represents one of the greatest treatment challenges to cardiac surgeons, and carries significant risk of morbidity and mortality. Arch surgery necessitates the cessation of systemic blood flow, placing the brain and kidneys at significant risk of ischaemic injury. To mitigate these risks, arch surgery was traditionally performed during deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (DHCA) [1, 2], a well-documented concept in reducing oxygen and metabolic requirements of hypoxic tissues. However, hypothermia is not without consequences, including prolonging cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) times, coagulopathy, multi-organ dysfunction, systemic inflammatory response and neuroapoptosis [3].

With the development of selective antegrade cerebral perfusion, by Bachet et al. and Kazui et al. [4, 5], continuous cerebral perfusion during arch surgery was made possible, changing the concept of total body circulatory arrest (CA) to lower body CA, leading to a shift to perform these surgeries closer to normothermia, possibly minimizing the adverse effects of hypothermia [3]. While retrospective and uncontrolled studies have demonstrated the safety of warmer temperatures [6–8], there is significant variation in these studies, and no temperature guidelines exist. The purpose of this study was to analyse our institutional experience in hemiarch replacement surgery using unilateral selective antegrade cerebral perfusion (uSACP) via the right axillary artery with mild hypothermia (32°C).

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient population and data

All patients (n = 83) undergoing hemiarch reconstruction with uSACP via right axillary artery cannulation and mild hypothermic CA (32 ± 2°C) between September 2011 and February 2018 at the University of Ottawa Heart Institute (UOHI) were included. Exclusions included acute type A dissections (n = 6), total arch replacement (n = 9) and patients with missing data (n = 2). This study received institutional ethics board approval (IRB# 20160408-01H) and individual patient consent was waived. Prospective perioperative data are routinely collected on all cardiac surgery patients, capturing information on preoperative, periprocedural and postoperative variables.

Study definitions and outcomes

Adverse outcomes included death (in-hospital and 30 day), temporary neurological dysfunction (TND), permanent neurological dysfunction (PND), delirium, myocardial infarction (MI), deep sternal wound infection, incidence of atrial fibrillation, acute kidney injury (AKI), renal failure requiring new dialysis and prolonged ventilation. Neurological end points used were in accordance with the International Aortic Arch Surgery Study Group [9]. TND was defined as neurological deficits without localizing signs and lasting <24 h without evidence of infarction on neurological imaging. PND or stroke was defined as new focal (embolic stroke) or global (coma) deficits which persist ≥72 h and confirmed by imaging. Delirium was diagnosed using the Confusion Assessment Method. Perioperative MI was diagnosed using electrocardiographic (new Q waves or a new left bundle branch block) and/or biochemical markers (elevations of creatine kinase myocardial band mass > 60 μg/l), in conjunction with echocardiographic (presence of new wall motion abnormalities). Deep sternal wound infection was diagnosed using Centre for Disease Control criteria [10]. Preoperative chronic kidney disease (CKD) was defined as a glomerular filtration rate <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 for 3 months or greater. Degree of kidney injury postoperatively was assessed using the Acute Kidney Injury Network classification system [11]. Prolonged ventilation was defined as mechanical ventilation >48 h.

Operative techniques

Invasive monitoring included Swan-Ganz catheters and bilateral radial arterial lines. A nasopharyngeal probe was used for core temperature monitoring. A Foley catheter with temperature probe was inserted to measure bladder temperature. Transcutaneous cerebral oximetry (INVOS 5100C) monitoring was used in all cases and intraoperative transoesophageal echocardiography assessment of all patients was performed.

All operations were initiated with axillary cannulation using an 8 mm Dacron graft and cannulated with a #22 Fr Elongated One-Piece Arterial Cannula. The right atrial appendage was used for venous drainage and a right superior pulmonary vein vent for left ventricular decompression. Cold blood cardioplegia was delivered antegrade via the ascending aorta. Once on CPB, the patient was systemically cooled to a mean core body temperature of 32°C.

Next, the innominate and left common carotid arteries were isolated and the proximal aorta was transected 1 cm above the sinotubular junction. The ascending aorta was then replaced with an appropriate-sized Gelweave graft and cardioplegia was readministered via the tube graft to ensure suitable anastomosis hemostasis.

Once target temperature was achieved, both the innominate and left common carotid arteries were clamped. Antegrade cerebral perfusion (ACP) was initiated at 28–34°C at a rate of 10–15 ml·kg−1·min−1. ACP flow was titrated to a cerebral perfusion pressure (measured at the right radial artery) of 60–70 mmHg. Cerebral oximetry was monitored to ensure equal left/right saturations. The cross-clamp was removed and the diseased portions of the aorta resected.

Distal aortic reconstruction was performed with an open bevelled anastomosis to the undersurface of the aortic arch using a Gelweave graft. The heart and aortic graft were then de-aired and the innominate and left common carotid clamps removed and whole body perfusion and rewarming started.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Continuous variables were reported as mean ± 1 SD or median for non-normally distributed variables. Categorical variables were reported as counts and percentages. Cumulative survival rates were calculated using Kaplan–Meier analysis. Follow-up was 100% complete and assessed through March 2019.

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics

A total of 66 patients with ascending and proximal aortic arch aneurysm undergoing ‘hemiarch’ replacement with mild hypothermia (32°C) and uSACP were included in this study. The mean age was 67 ± 3 years, of whom 43 (64%) were male. The maximal mean aortic diameter was 55 ± 10 mm. Aortic root aneurysm occurred in 6 (9%) patients. Mean left ventricular ejection fraction was 58 ± 6%. Concomitant aortic valve pathology occurred in 51 (77%) patients with specific aetiologies, as well as baseline patient demographics are listed in Table 1. The incidence of prior transient ischaemic attack and stroke was 1% and 3%, respectively. Mean creatinine was 90 ± 73 µmol/l, with 5 (8%) patients suffering from CKD and 1 (2%) patient on preoperative dialysis. Fourteen (21%) cases were re-do, of which 10 (15%) patients had previous aortic surgery.

Table 1:

Preoperative patient characteristics

| Characteristic | Number (%) or mean ± SD (range) (n = 66) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 67 ± 13 |

| Gender (male) | 43 (65) |

| Height (cm) | 169 ± 10 |

| Weight (kg) | 80 ± 20 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28 ± 6 |

| LVEF (%) | 58 ± 6 |

| Aortic aneurysm | |

| Aortic root (%) | 6 (9) |

| Ascending aorta (%) | 66 (100) |

| Aortic arch (%) | 66 (100) |

| Maximal aortic diameter (mm) | 55 ± 10 |

| Aortic valve pathology | |

| Bicuspid AV (%) | 6 (9) |

| AI (%) | 36 (55) |

| AS (%) | 9 (14) |

| Chronic dissection (%) | 1 (2) |

| CAD (%) | 20 (30) |

| TIA (%) | 1 (2) |

| Stroke (%) | 2 (3) |

| COPD (%) | 6 (9) |

| DM (%) | 7 (11) |

| HTN (%) | 39 (59) |

| DLP (%) | 25 (38) |

| Smoking (%) | 20 (30) |

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 10 (15) |

| Cr (µmol/l) | 90 ± 73 |

| CKD (%) | 5 (8) |

| Dialysis (%) | 1 (2) |

| Prior cardiac surgery (%) | 14 (21) |

| Prior aortic surgery (%) | 10 (15) |

AI: aortic insufficiency; AS: aortic stenosis; AV: aortic valve; BMI: body mass index; CAD: coronary artery disease; CKD: chronic kidney disease; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; Cr: creatinine; DLP: dyslipidaemia; DM: diabetes; HTN: hypertension; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; SD: standard deviation; TIA: transient ischaemic attack.

Surgical procedures and perioperative data

The majority (86%) of patients underwent elective surgery, with the remaining undergoing urgent surgery. All patients in the series underwent hemiarch replacement. Fourteen (21%) patients had a concomitant aortic (valve sparing) root replacement, 4 (6%) patients underwent Bentall procedure and 48 (73%) patients had supracoronary ascending aortic replacements. An additional 33 (50%) patients underwent aortic valve repair, while 12 (18%) patients had a replacement, and 11 (17%) underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (Table 2).

Table 2:

Surgical procedures and perioperative data

| Procedure/variable | Number (%) or mean ± SD (range) (n = 66) |

|---|---|

| Priority | |

| Elective (%) | 57 (86) |

| Urgent (%) | 9 (14) |

| Extent of aortic replacement | |

| Valve sparing root (%) | 14 (21) |

| Bentall procedure (%) | 4 (6) |

| Supra-coronary only (%) | 48 (73) |

| Aortic valve surgery | |

| Repair (%) | 33 (50) |

| Replacement (%) | 12 (18) |

| Mitral valve surgery (%) | 2 (3) |

| CABG (%) | 11 (17) |

| TEVAR (%) | 1 (2) |

| Cannulation strategy | |

| Axillary (%) | 63 (95) |

| Innominate (%) | 3 (5) |

| Lowest NP temperature (°C) | 32 ± 2 |

| CPB time (min) | 137 ± 49 |

| Cross-clamp time (min) | 88 ± 42 |

| Circulatory arrest time (min) | 17 ± 5 |

| Reperfusion time (min) | 35 ± 16 |

| Intraoperative transfusion (%) | 29 (44) |

| pRBC (units) | 1 ± 1 |

| FFP (units) | 1 ± 2 |

| Plt (units) | 0 ± 1 |

| Cryo (units) | 0 ± 2 |

CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; CPB: cardiopulmonary bypass; Cryo: cryoprecipitate; FFP: fresh frozen plasma; NP: nasopharyngeal; Plt: platelet; pRBC: packed red blood cells; SD: standard deviation; TEVAR: thoracic endovascular aortic repair.

The lowest mean core body temperature during CA was 32 ± 2°C. The average duration of CA was 17 ± 5 min. Mean CPB time was 137 ± 49 min and mean cross-clamp time was 88 ± 42 min. Intraoperative transfusions occurred in 29 (44%) patients, with packed red blood cells and fresh frozen plasma transfused most often.

Intraoperative and metabolic data

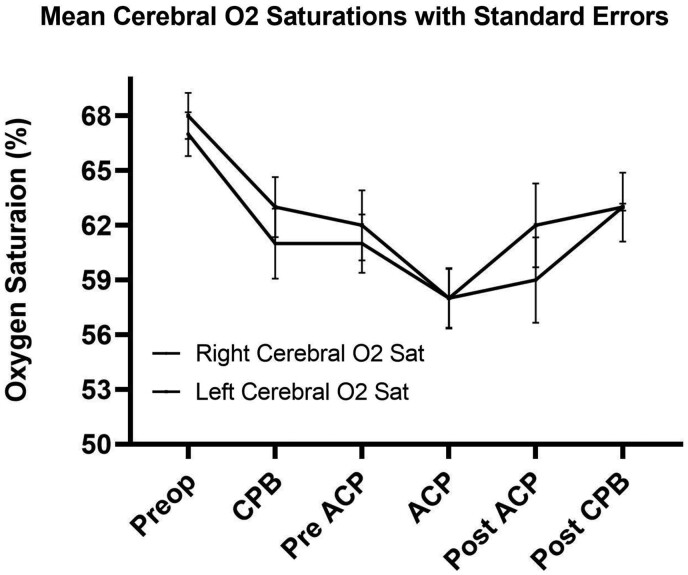

Mean cerebral O2 saturations from both right and left probes were similar throughout surgery. The lowest O2 saturations occurred during ACP (58 ± 2%) (Fig. 1). Blood pH remained stable, but dropped post-ACP, with the lowest value occurring post-CPB at 7.18 ± 0. Patient CO2 levels remained within normal limits until cessation of ACP, rising to their maximum (46 ± 2 mmHg) and then dropping to their lowest post-CPB (39 ± 1 mmHg) (Table 3). Lowest base excess values occurred post-ACP (−4.6 ± 1 mEq/l) and post-CPB (−3.7 ± 1 mEq/l). Lactate levels peaked post-ACP at 4.6 ± 0 mmol/l, and then returned to pre-ACP levels postoperatively at 2.6 ± 0 mmol/l (Fig. 2).

Figure 1:

Mean perioperative cerebral O2 saturations with standard error. ACP: antegrade cerebral perfusion; CPB: cardiopulmonary bypass; Preop: preoperative.

Table 3:

Intraoperative and metabolic data

| Number (%) or mean ± SE (n = 66) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Preop | CPB | Pre-ACP | ACP | Post-ACP | Post-CPB |

| Mean right cerebral O2 (%) | 67 ± 1 | 61 ± 2 | 61 ± 2 | 58 ± 2 | 59 ± 2 | 63 ± 2 |

| Mean left cerebral O2 (%) | 68 ± 1 | 63 ± 2 | 62 ± 2 | 58 ± 2 | 57 ± 2 | 60 ± 2 |

| Mean pH | 7.40 ± 0 | 7.38 ± 0 | 7.36 ± 0 | 7.36 ± 0 | 7.28 ± 0 | 7.18 ± 0 |

| Mean pCO2 (mmHg) | 41 ± 1 | 40 ± 1 | 42 ± 1 | 43 ± 3 | 46 ± 2 | 39 ± 1 |

| Mean O2 (mmHg) | 99.5 ± 0 | 96.7 ± 1 | 99.5 ± 0 | 99.6 ± 0 | 99.4 ± 0 | 99.7 ± 0 |

| Mean base excess (mEq/l) | 0.2 ± 0 | −1.1 ± 0 | −1.6 ± 0 | −2.2 ± 0 | −4.6 ± 1 | −3.7 ± 1 |

ACP: antegrade cerebral perfusion; CPB: cardiopulmonary bypass; Preop: preoperatively.

Figure 2:

Mean perioperative metabolic data (pH, pCO2, base excess and lactate) with standard error. ACP: antegrade cerebral perfusion; CPB: cardiopulmonary bypass; Preop: preoperative.

Postoperative outcomes

PND occurred in 1 (2%) patient, who had a total CA time of 20 min. TND occurred in 2 (3%) patients with CA times of 15 and 30 min, respectively. Both patients with TND had transient ischaemic attack, with no acute findings on computed tomography (CT) and had full symptom resolution within 24 h. Postoperative delirium occurred in 2 (3%) patients. No paraplegia occurred in the series (Table 4).

Table 4:

Postoperative outcomes

| Variable | Number (%) or mean ± SD (range) (n = 66) |

|---|---|

| Mortality (%) | 0 (0) |

| TND (%) | 2 (3) |

| PND (%) | 1 (2) |

| Delirium (%) | 2 (3) |

| Seizures (%) | 1 (2) |

| MI (%) | 0 (0) |

| DSWI (%) | 3 (5) |

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 29 (44) |

| AKI stage | |

| Stage 1 (%) | 8 (12) |

| Stage 2 (%) | 0 (0) |

| Stage 3 (%) | 3 (5) |

| New dialysis (%) | 3 (5) |

| Ventilation time (days) | 2 ± 5 |

| Prolonged ventilation (%) | 8 (12) |

| ICU stay (days) | 4 ± 7 |

| Hospital stay (days) | 13 ± 13 |

| Postoperative pRBC transfusion (%) | 16 (24) |

| pRBC (units) | 1 ± 3 |

AKI: acute kidney injury; Cr: creatinine; DSWI: deep sternal wound infection; ICU: intensive care unit; MI: myocardial infarction; PND: permanent neurological dysfunction; pRBC: packed red blood cells; SD: standard deviation; TND: temporary neurological dysfunction.

For the entire series, 8 (12%) patients suffered stage 1 AKI and 3 (5%) patients stage 3 AKI. New temporary dialysis occurred in 3 (5%) patients. The first patient had a CA time of 17 min and required continuous renal replacement therapy for 8 days, in context of solitary kidney. The second patient had a CA time of 22 min and required ischaemic heart disease for 1 month. The third patient had a CA time of 14 min and required continuous renal replacement therapy for 4 days (stage 3 AKI). The last stage 3 AKI patient did not require dialysis, and had undergone a concomitant thoracic endovascular aortic repair procedure with dye load the likely cause.

The most frequent postoperative complication was atrial fibrillation, occurring in 29 patients (44%). The average length of intensive care unit and hospital stay was 4 ± 7 and 13 ± 13 days, respectively. Postoperative packed red blood cells transfusion occurred in 16 (24%) patients with an average of 1 ± 3 units transfused.

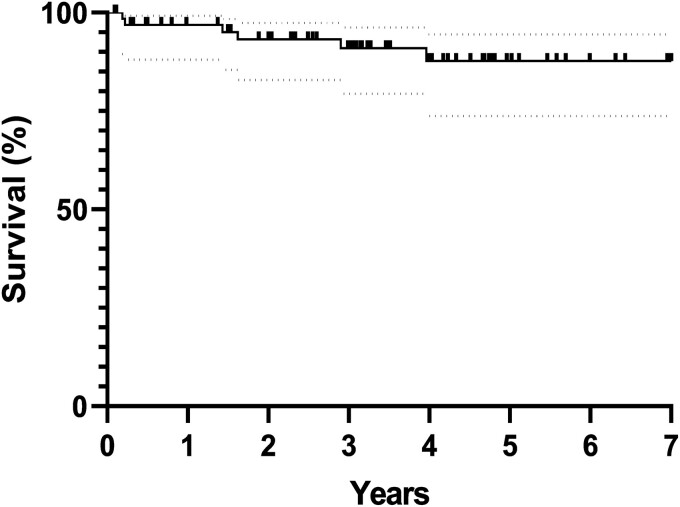

Survival

The intraoperative and 30-day mortality rate was 0%. At late follow-up (mean 3.2 ± 4.8 years, 100% complete), 60 patients (91%) were still alive. Survival rates are demonstrated in Fig. 3, with 97%, 91% and 88% survival at 1, 3 and 5 years, respectively. Of the 6 patients who died, the causes of death were: sepsis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation, acute type B dissection, cancer and 2 were unknown.

Figure 3:

Long-term survival estimates post-hemiarch replacement with antegrade cerebral perfusion and mild hypothermia. Numbers of patients at risk at 1 year (64), 3 years (61) and 5 years (60) are displayed below. 95% confidence interval are depicted by the dotted lines.

DISCUSSION

Aortic arch reconstruction remains a significant surgical challenge due to the need for hypothermic CA and risk of neurological injury and end-organ damage. With the development of ACP, hypothermia now plays a secondary role in cerebral protection, prompting further question of the optimal method and temperature during CA. Our protocol for cerebral protection during hemiarch surgery consists of uSACP via right axillary cannulation and mild hypothermic CA (32°C).

Aortic arch surgery carries a significant burden of neurological injury [12–14] with PND rates reported as high as 9% [13], leading to increased mortality, morbidity and healthcare costs [6]. To reduce these rates, surgeons have utilized continuous cerebral perfusion in conjunction with DHCA, with significant reductions in the incidence of adverse neurological outcomes and mortality [15]. Despite these advancements, high morbidity and mortality rates have persisted and may be secondary to profound hypothermia [7]. Consequently, we have seen a paradigm shift towards warmer CA temperatures with positive neurological outcomes being observed [16, 17]. Tian et al. performed a recent meta-analysis of 9 studies comparing DHCA and moderate hypothermic CA (MHCA) with ACP [18]. Stroke rates were found to be significantly lower in patients undergoing MHCA with ACP (P = 0.0007), with comparable outcomes for TND, renal failure and mortality [25].

Further reductions in CA temperatures were investigated by Leshnower et al., where they compared mild (28.6°C) vs moderate (24.3°C) hypothermia in 500 patients undergoing hemiarch replacement using uSACP [6]. Without differences in mortality, need for dialysis and TND observed, they found a significant reduction in PND in the mild hypothermic group (P = 0.02). Multiple studies have also corroborated the low incidence of PND in uSACP and mild hypothermia, which are also comparable to DHCA patients in literature [7].

Similarly, we observed a low incidence of PND (2%) and TND (3%) in our study. Only one patient developed PND, with posterior cerebral artery territory ischaemic stroke manifesting as occipital lobe infarct on CT scan, believed to be embolic in nature. This patient had a prior history of stroke and craniotomy, both likely risk factors for PND. CA time in this patient was 20 min. Both patients who suffered TND had previous histories of neurological events (1 patient with a previous transient ischaemic attack and 1 patient with a previous stroke). No acute findings were found on CT and both patients had resolution of neurological deficits in 24 h. All patients in our study who experienced a neurological event had prior cerebrovascular disease and is in accordance with literature identifying cerebrovascular disease as a risk factor for neurological dysfunction in arch surgery [19]. Our results support neurological safety at upper limits of mild hypothermic CA.

There have been little prospective data comparing degree of hypothermia during CA using mandatory radiographic end points. Leshnower et al. performed a prospective randomized trial of 20 patients undergoing hemiarch repair, comparing MHCA (26°C) with ACP to DHCA (19°C) with retrograde cerebral protection, with neurologist-adjudicated examinations and postoperative neuroimaging. Like our study, Leshnower et al. [20] reported low levels of neurological dysfunction (11%) with MHCA + ACP, and demonstrated no statistical differences in the incidence of clinical neurological injury compared to deep hypothermia + retrograde cerebral protection. However, an increased incidence of radiographic cerebral injury was observed on magnetic resonance imaging-diffusion-weighted imaging in the moderate hypothermia-ACP group 100% vs 45% in the deep hypothermia − retrograde cerebral protection group, and was the sole driver for the statistical difference (P < 0.01) between groups in their primary end point. Despite a lack of power, this study suggests a higher prevalence of silent cerebral infarcts with higher temperature; however, the long-term clinical significance of these injuries remains unknown.

With almost complete neurological protection using ACP, CA is now limited to lower body CA only, placing distal organs at ischaemic risk. Both Di Eusanio et al. and Zierer et al. [12, 21] have reported postoperative rates of renal dysfunction (postoperative creatinine level of > 250 µmol/l) during hemiarch replacement and ACP of 8% (with DHCA) and 10% (with mild hypothermic CA), respectively. Using this definition, we had a 7.5% incidence of renal dysfunction, supporting the safety of mild hypothermic CA on renal organ protection.

The low incidence of renal dysfunction and dialysis in our study was not associated with any perioperative factors such as temperature, length of CA or preoperative CKD. A total of 5 patients had preoperative CKD. The incidence of AKI requiring dialysis postoperatively in our study was 5% (n = 3). No patients required permanent renal replacement therapy. These results are consistent with Leshnower et al. [6], who demonstrated a 4% incidence of dialysis-dependent renal failure with mild hypothermia and ACP.

Operative mortality rates for arch surgery range from 5% to 30% [1, 3, 22, 23], and are dependent on numerous factors including temperature, cerebral perfusion strategy, length of CA and CPB, extent of repair, and presence of aortic dissection. In a study of 245 patients undergoing aortic arch replacement with ACP and mild hypothermia (30.5 ± 1.4°C), Zierer et al. [21] observed an operative mortality rate of 8% (n = 20). We observed no in-hospital or 30-day mortality. Long-term survival (3.2 ± 4.8 years) was also high, with an 88% survival rate at 5 years (Fig. 3). However, the exclusion of patients undergoing total arch replacements and acute type A dissections may have contributed to our lower mortality rates.

Examining the metabolic impact of mild hypothermia, post-ACP patients developed mild metabolic acidosis (pH 7.28), with base excess −4.6 ± 1mEq/l. Post-CPB, base excess normalized indicating appropriate respiratory compensation. Hyperlactaemia after cardiac surgery is common, and is linked to CPB, cardioplegia, hypothermia and is a recognized independent risk factor for mortality, cardiogenic shock and dialysis-dependent renal dysfunction [24]. Lactate level increased to their maximum post-lower body CA at 4.6 ± 1 mmol/l, consistent with anaerobic metabolism of the lower body, and normalized to pre-ACP levels post-CPB (Fig. 2).

Although our study demonstrates this strategy in limited arch disease, and non-emergent cases, it can be deployed in setting of acute aortic dissection limited to the ascending aorta and proximal arch, and is the standard of treatment at our institution. If the lower body CA time is expected to be greater than 20 min, we would then institute hypothermia closer to 26–28°C. As the aortic pathology begins to involve the arch, a total arch replacement may be necessary. We believe the same strategy under moderate hypothermia (20.1–28°C) to be optimal, with the addition of other cerebral protective adjuncts, such as bilateral ACP in cases where there is a large difference between left and right cerebral saturations.

Based on the results of this study, our centre has initiated a randomized control trial (COMMENCE) comparing mild hypothermia (32 ± 1°C, Treatment Group) versus moderate hypothermia (26 ± 1°C, Control Group) CA in hemiarch surgery powered for a composite outcome of neurological and AKI. This is a prospective multicentre, single-blind 2-arm randomized control trial of 282 patients undergoing hemiarch surgery with uSACP across Canada (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02860364). It is hoped that performing hemiarch surgery using mild hypothermiaand uSACP will result in a 15% absolute risk reduction in our composite outcome, which will translate into improved patient outcomes, survival and long-term costs.

As a retrospective analysis, our study is open to procedural biases, as well as informational and recall bias. Data supporting adequate distal organ perfusion were based solely on the incidence of postoperative AKI and arterial blood gas samples, not accounting for hepatic injury. Furthermore, the metabolic data presented were obtained from a limited subset of patients. Lastly, a diagnosis of neurological dysfunction was based exclusively on clinical assessment and neuroradiographical evidence, not accounting for neurocognitive deficits.

CONCLUSIONS

The data presented in this manuscript support the safe use of mild hypothermic CA and uSACP via the right axillary artery during hemiarch reconstruction. This study is one of the few studies to have examined the outcomes of hemiarch surgery at the upper limits of mild hypothermia (32°C ± 2). Using the strategy described herein, our study has demonstrated sufficient cerebral protection, adequate distal organ perfusion and no perioperative mortality. Our current randomized control trial, COMMENCE, is underway and will provide the definitive outcomes of mild hypothermia on neurocognitive function and end-organ malfunction needed to demonstrate superiority of mild hypothermic CA in the treatment of arch pathologies.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Author contributions

Habib Jabagi: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing. Nadzir Juanda: Conceptualization; Methodology; Writing—original draft. Alex Nantsios: Conceptualization; Investigation; Methodology; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing. Munir Boodhwani: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Supervision; Writing—original draft.

Reviewer information

Interactive CardioVascular and Thoracic Surgery thanks Luca Di Marco, Konstantinos Tsagakis and the other, anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review process of this article.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ACP

Antegrade cerebral perfusion

- AKI

Acute kidney injury

- CA

Circulatory arrest

- CKD

Chronic kidney disease

- CPB

Cardiopulmonary bypass

- CT

Computed tomography

- DHCA

Deep hypothermic circulatory arrest

- MHCA

Moderate hypothermic CA

- MI

Myocardial infarction

- PND

Permanent neurological dysfunction

- TND

Temporary neurological dysfunction

- uSACP

Unilateral selective antegrade cerebral perfusion

REFERENCES

- 1. Griepp RB, Stinson EB, Hollingsworth JF, Buehler D.. Prosthetic replacement of the aortic arch. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1975;70:1051–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Englum BR, Andersen ND, Husain AM, Mathew JP, Hughes GC.. Degree of hypothermia in aortic arch surgery—optimal temperature for cerebral and spinal protection: deep hypothermia remains the gold standard in the absence of randomized data. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2013;2:184–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Urbanski PP, Lenos A, Bougioukakis P, Neophytou I, Zacher M, Diegeler A.. Mild-to-moderate hypothermia in aortic arch surgery using circulatory arrest: a change of paradigm? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2012;41:185–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bachet J, Goudot B, Dreyfus G, Al Ayle N, Aota M, Banfi C. et al. How do we protect the brain? Antegrade selective cerebral perfusion with cold blood during aortic arch surgery. J Card Surg 1997;12(2 Suppl):193–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kazui T, Washiyama N, Muhammad BAH, Terada H, Yamashita K, Takinami M.. Improved results of atherosclerotic arch aneurysm operations with a refined technique. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2001;121:491–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Leshnower BG, Myung RJ, Thourani VH, Halkos ME, Kilgo PD, Puskas JD. et al. Hemiarch replacement at 28°C: an analysis of mild and moderate hypothermia in 500 patients. Ann Thorac Surg 2012;93:1910–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kamiya H, Hagl C, Kropivnitskaya I, Bothig D, Kallenbach K, Khaladj N. et al. The safety of moderate hypothermic lower body circulatory arrest with selective cerebral perfusion: a propensity score analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007;133:501–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pacini D, Leone A, Di Marco L, Marsilli D, Sobaih F, Turci S. et al. Antegrade selective cerebral perfusion in thoracic aorta surgery: safety of moderate hypothermia. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2007;31:618–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yan TD, Tian DH, LeMaire SA, Hughes GC, Chen EP, Misfeld M. et al. Standardizing clinical end points in aortic arch surgery: a consensus statement from the International Aortic Arch Surgery Study Group. Circulation 2014;129:1610–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA.. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am J Infect Control 2008;36:309–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, Warnock DG. et al. Acute kidney injury network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2007;11:R31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nakamura K, Onitsuka T, Yano M, Yano Y, Saitoh T, Kojima K. et al. Predictor of neurologic dysfunction after elective thoracic aorta repair using selective cerebral perfusion. Scand Cardiovasc J 2005;39:96–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ergin MA, Galla JD, Lansman S L, Quintana C, Bodian C, Griepp RB.. Hypothermic circulatory arrest in operations on the thoracic aorta. Determinants of operative mortality and neurologic outcome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1994;107:788–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Di Eusanio M, Schepens MA, Morshuis WJ, Di Bartolomeo R, Pierangeli A, Dossche KM.. Antegrade selective cerebral perfusion during operations on the thoracic aorta: factors influencing survival and neurologic outcome in 413 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2002;124:1080–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kamenskaya OV, Klinkova AS, Chernyavsky AM, Lomivorotov VV, Meshkov IO, Karaskov AM.. Deep hypothermic circulatory arrest vs. antegrade cerebral perfusion in cerebral protection during the surgical treatment of chronic dissection of the ascending and arch aorta. J Extra Corpor Technol 2017;49:16–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Leshnower BG, Myung RJ, Kilgo PD, Vassiliades TA, Vega JD, Thourani VH. et al. Moderate hypothermia and unilateral selective antegrade cerebral perfusion: a contemporary cerebral protection strategy for aortic arch surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2010;90:547–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Leshnower BG, Myung RJ, Chen EP.. Aortic arch surgery using moderate hypothermia and unilateral selective antegrade cerebral perfusion. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2013;2:288–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kumral E, Yüksel M, Büket S, Yagdi T, Atay Y, Güzelant A.. Neurologic complications after deep hypothermic circulatory arrest: types, predictors, and timing. Tex Heart Inst J 2001;28:83–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Svensson LG, Crawford ES, Hess KR, Coselli JS, Raskin S, Shenaq SA. et al. Deep hypothermia with circulatory arrest. Determinants of stroke and early mortality in 656 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1993;106:19–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Leshnower BG, Rangaraju S, Allen JW, Stringer AY, Gleason TG, Chen EP.. Deep hypothermia with retrograde cerebral perfusion versus moderate hypothermia with antegrade cerebral perfusion for arch surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2019;107:1104–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zierer A, Detho F, Dzemali O, Aybek T, Moritz A, Bakhtiary F.. Antegrade cerebral perfusion with mild hypothermia for aortic arch replacement: single-center experience in 245 consecutive patients. Ann Thorac Surg 2011;91:1868–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zierer A, Moritz A.. Cerebral protection for aortic arch surgery: mild hypothermia with selective cerebral perfusion. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;24:123–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bakhtiary F, Dogan S, Dzemali O, Kleine P, Moritz A, Aybek T.. Mild hypothermia (32°C) and antegrade cerebral perfusion in aortic arch operations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2006;132:153–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hajjar LA, Almeida JP, Fukushima JT, Rhodes A, Vincent J-L, Osawa EA. et al. High lactate levels are predictors of major complications after cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013;146:455–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tian DH, Wan B, Bannon PG, Misfeld M, LeMaire SA, Kazui T. et al. A meta-analysis of deep hypothermic circulatory arrest versus moderate hypothermic circulatory arrest with selective antegrade cerebral perfusion. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2013;2:148–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]