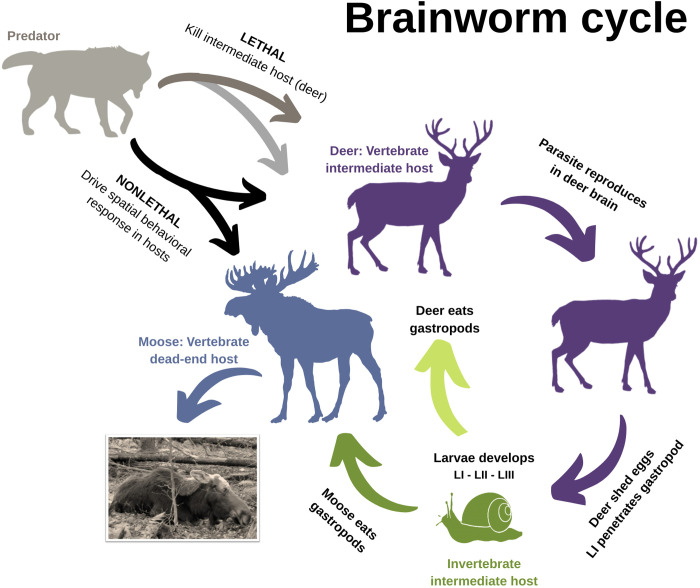

Fig. 1. Hypothesized predator impact on P. tenuis transmission cycle between white-tailed deer (O. virginianus) and moose (A. alces).

The parasite P. tenuis replicates within the white-tailed deer, the definitive vertebrate host (purple). Deer shed the parasite’s first-stage larvae through feces, which then infect terrestrial gastropods (snails and slugs) to develop to third-stage larvae (green). Infectious gastropods are incidentally consumed by white-tailed deer (light green arrow), in which the life cycle continues with further development to the adult stage and reproduction, or moose (green arrow), where infections are fatal and the parasite is unable to complete its life cycle (blue arrow). Wolves (gray) are hypothesized to trigger lethal and nonlethal cascade effects that influence parasite transmission from deer to moose. For example, deer are a primary prey species of wolves in Minnesota; thus, predation modulates deer density, which would consequently reduce P. tenuis shedding into the environment (dark gray arrow). Wolves also remove P. tenuis–infected, sick moose from the system, although this would not be expected to affect transmission because moose are an aberrant host [light gray arrow; (25, 26)]. We postulated and tested in this study the existence of nonlethal mechanisms (black arrows), such as behavioral responses by prey to predator presence, that influence habitat use and prey species overlap, where a reduction in the latter would reduce risk of parasite transmission between prey species. Inset: Moose exhibiting P. tenuis–induced neurological signs (80).