Abstract

Among many, poly(lactic acid) (PLA) has received significant consideration. The striking price and accessibility of l-lactic acid, as a naturally occurring organic acid, are important reasons for poly-(l)-lactic acid (PLLA) improvement. PLLA is a compostable and biocompatible/bioresorbable polymer used for disposable products, for biomedical applications, for packaging film, in the automotive industry, for electronic device components, and for many other applications. Formerly, titanium and other metals have been used in different orthopaedic screws and plates, but they are not degradable and therefore remain in the body. So, the development of innovative and eco compatible catalysts for polyester synthesis is of great interest. In this study, an innovative and eco sustainable catalyst was employed for PLLA synthesis. The combined CeCl3·7H2O–NaI system has been demonstrated to be a very valuable and nontoxic catalyst toward PLLA synthesis, and it represents a further example of how to exploit the antibacterial properties of cerium ions in biomaterials engineering. A novel synthesis of poly-(l)-lactic acid was developed in high yields up to 95% conversion and with a truly valuable molecular weight ranging from 9000 to 145 000 g mol−1, testing different synthetic routes.

The combined CeCl3·7H2O–NaI system has demonstrated to be a very valuable and nontoxic catalyst toward PLLA synthesis.

Introduction

The development of bio-based polymers to substitute or decrease the use of polymers from petrochemical resources continues to show an increasing growth. In recent years in fact, the enlargement of degradable polyester syntheses, became more popular due to both environmental and strategic reasons. First of all, biopolymers are a well-known class of materials derived from organic products like milk derivatives and cellulose, which show a very easy degradation pattern. Furthermore, they are really important materials in the biomedical field,1 and the advent of these polymers has significantly influenced the development and rapid growth of various technologies in modern medicine.2 This involves greater attention both in their preparation and in their use and disposal (reuse, recycling, and recovery). Thus, the susceptibility of aliphatic polyesters to bio degradative processes,3 and the presence of contaminants due to the promoters employed in their industrial production, must be carefully considered.4 For this reason, practical and feasible catalytic systems, which allow minor contamination of the polymeric material especially when it may be potentially applied in biomedicine are welcomed. With this paper we wish to make available our efforts on the use of non-toxic and low environmental impact catalysts in the development of strategies useful for the preparation of polyesters.5

Poly-l-(lactic acid) (PLLA) belongs to the family of polymers commonly made from α-hydroxy acids such as lactic acid (2-hydroxypropionic acid). Three are the main routes usually used to synthetize PLA, depending on the molecular weight of the resulting aliphatic polymer, namely, a direct condensation polymerization, a combined melt polycondensation with a Solid State Process (SSP) starting from oligomers in the presence of tin, titanium or zinc based catalysts,6–11 and the last is the ring-opening polymerization (ROP),12 starting from a purified lactide structure.13,14

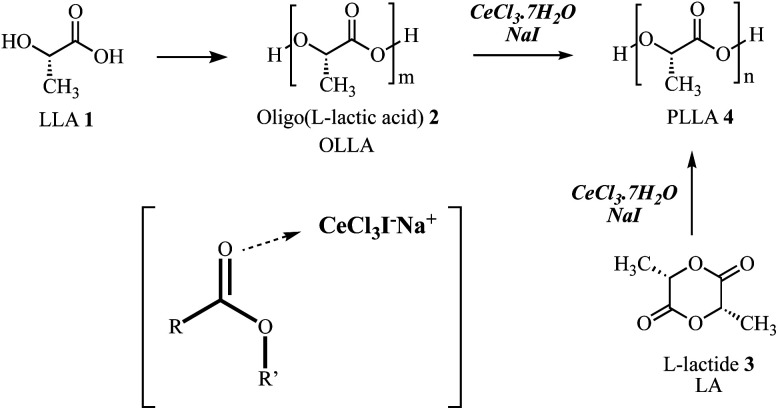

Lewis acids have significantly increased their use, and eco-friendly Lewis acid catalysts are available, but particular attention must be directed to their toxicity and to the contamination of the final polymer product especially in the biomedical field. In recent years, multimetallic catalysts are receiving increasing attention in the catalysis of polycondensation reactions that can lead to the formation of polymeric structures.15 A very interesting example is the recent methodology developed by J. A. Garden et al.16 in the use of heterometallic complex catalysts to obtain aliphatic polyesters such as poly(lactic acid). It is a typical academic demonstration of what has been studied in these last decades and namely, that the multimetallic catalysis based on the combined action of different metals in a chemical transformation, amplifies the activity of the single metal. Thus, the proximity between the metal centers, seems to provide favorable conditions for the occurrence of enhanced catalytic properties.17 Up to date, however, this greater catalytic activity, consequence of the heterometallic cooperativity of multimetallic catalysts, is followed by two major application difficulties. First, the assessment of the environmental effects of multimetallic substances requires information on potential combination effects.18 Secondly, the long-term stability of the molecular structures of heterometallic complexes is an omnipresent and pressing concern in industrial processes.19 For the latter reason the most used catalysts in PLA synthesis are the tin(ii) salts and the most used are the commercially available SnCl2 or [Sn(Oct)2].20–23 So, the search for useful catalysts for aliphatic polyesters synthesis is a truly big challenge. In the last years, inexpensive, water tolerant, non-toxic,24 and easy to handle cerium trichloride heptahydrate (CeCl3·7H2O) has attracted considerable attention because of its diverse applications as a Lewis acid catalyst in organic synthesis.25 In line with our research interests in exploring new and more concise procedures for polymer formation promoted by Lewis acids, we have increased the potentialities of the combination of CeCl3·7H2O with NaI,26 capable of transforming the typical aggregates of metal halides such as CeCl3 into the corresponding more reactive monomeric structures.27 In addition to our knowledge on the efficiency of CeCl3·7H2O–NaI system, Fedynshkin et al. reported the oligo-lactic acid thermal decomposition promoted by CeCl3·7H2O,28 suggesting us that the use of an appropriate amount of catalyst CeCl3·7H2O–NaI can facilitate the synthesis of the corresponding polyester. Thus, we tested a new, efficient and eco-sustainable CeCl3·7H2O–NaI catalyst following two different reaction processes. Our catalytic procedure (Scheme 1) demonstrated to be very efficient in a two-step synthesis of poly-(l-lactic acid) 4 starting from a polycondensation step in which a prepolymer oligo-(l-lactic acid) (OLLA) 2 has been obtained, followed by a CeCl3·7H2O–NaI melt-solid state (SSP) polycondensation that provides PLLA 4 with a molecular weight ranging between 2000 and 146 000 g mol−1. Furthermore, we defined a new strategy for PLLA synthesis, starting from l-lactide 3, using the same cerium(iii)–NaI catalytic system for the ring opening polymerization reaction under microwaves irradiation, which provides a polymer in a high percentage of conversion and very good molecular weights, boosting the reaction rate up to 1 hour.

Scheme 1. General synthesis of PLLA using CeCl3·7H2O–NaI as catalytic system with m < n, and cerium(iii) salts-sodium iodide activation of the ester group reported by Marcantoni et al.29,30.

Results and discussion

CeCl3·7H2O–NaI physical characterization

The XPS technique has been applied for the characterization of the multimetallic CeCl3·7H2O–Nal catalyst. The typical structure of the commercially available cerium trichloride is CeCl3·7H2O, where the CeCl3 molecule incorporate seven water molecules. The structure of this heptahydrate cerium trichloride (CeCl3·7H2O) consists of dimers [CeCl3(H2O)7]2, as shown by L. A. Boatner et al.31,32 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Crystal structure of CeCl3·7H2O. The Ce coordination polyhedral are shaded in yellow, oxygen atoms are in red, chlorine atoms are in green, and hydrogen atoms are in blue.

This remarkable ability of water of crystallization can find explanation in its coordination that makes easy the disaggregation of the crystal lattice of cerium salt which might lead to a notable increase in the Lewis acidity of the cerium available at the particle surface.33 This hydrophobic amplification concept34 have been shown in several catalyzed CeCl3·7H2O organic transformations.35,36 To confirm the mechanistic role of the NaI we have analyzed the interaction between CeCl3·7H2O with NaI by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, in order to analyze the chemical shift in the core level binding energies.37 Fundamental reasons for this are the inherent element specificity of the associated element core level binding energies, and also the sensitivity both to the amount of the element present and its localization at the surface, the latter characteristic caused by the short mean free path of low energy (30–1000 eV) photoelectrons in the solids.38,39 We have started from a belief that CeCl3 is a rare-earth trihalides whose initial state is f1 (Ce = [Xe]4f15d16s2) as no promotion of f electron is required for a trivalent bonding with chlorine. Nevertheless, in the final state the charge transfer energy defined as the energy required to take an electron from the ligand p level to the unoccupied 4f level (about 9.7 eV)40 (f2v) is less than the value of the 4f-core hole Coulomb attraction (12.2 eV). This leads to a f2v satellite (where v is the hole in the valence) at about 3.4 eV lower binding energy. Intensity and energy of this satellite are sensitive to the degree of hybridization of the f states with the conduction states.41 We reported the XPS measurements42 of the 3d core level in CeCl3·7H2O and CeCl3·7H2O–NaI (Fig. 2 in (a) and (b) respectively).

Fig. 2. The XPS spectra of fine powdered samples of: (a) CeCl3·7H2O and (b) CeCl3·7H2O–NaI.

From the present study we cannot observe a variation within few percent in the intensity of the f2 satellite, indicating that the introduction of the NaI in the system does not vary the degree of the hybridization of the f states with conduction states. Such as hybridization is certainly enhanced for both samples with respect to the only CeCl3 molecular structure,43 but this property is conserved after the insertion of NaI. Furthermore, it can be excluded the presence of an initial f0 (metallic) state due to the promotion of the “f” electron in the valence bond (Fig. 2). Such a peak is in general observed at 10 eV higher binding energies. These results, thus, suggest us that there is not a direct interaction between cerium(iii) site and iodide ion. The activity of CeCl3·7H2O–NaI system is mainly exerted in the heterogeneous phase and, above all, we believe that a chloro-bridged oligomeric structure of CeCl3·7H2O is easily broken by donor species such as iodide ion. The resulting monomeric CeCl3·7H2O–NaI complex is a more active Lewis acid promoter.

Two-step synthesis of poly(lactic acid) by a melt polycondensation – solid state process (SSP)

The prepolymer was first synthetized by direct polycondensation of LLA and several different catalysts were investigated (Table S1†), using 0.1 mol% of the catalyst. As reported CeCl3·7H2O and CeCl3·7H2O–NaI (1 : 1 ratio) system were compared, resulting in a more active catalytic activity of the latter, with a weight average molecular weight, Mw = 3600 g mol−1. The Mn of oligolactic acid 2 (OLLA) was determined by 1H-NMR analysis and the results were compared with those obtained with a gel permeation chromatography (GPC). From the 1H-NMR analysis the degree of polymerization (DP) and the Mn of the prepolymer were determined by obtaining the ratio of proton integrals of the oligomeric chain (Fig. S1,† peak a and peak c) to that of end-groups as reported in eqn (1).44

|

1 |

The polymerization conversions are reported in Table S1† with different Lewis acids. In Table S1† it is also reported the onset temperature (Ton) (Fig. S2†). The highest value obtained was around 270 °C, confirming the low molecular weight of 2. The best results were obtained with monomeric CeCl3·7H2O–NaI combination (Table S1,† entry S1g) being this catalyst able to coordinate oxygen atoms and to push the reaction to the elimination of water. Then, different iodide sources were screened in order to ensure the high catalytic activity of cerium(iii) Cl3–NaI couple, KI and CuI gave lower efficiency than that of the CeCl3·7H2O–NaI system (Table 1).

Screening of iodide source in CeCl3·7H2O–MxIy catalysts.

| Entry | Catalyst | M n a (g mol−1) | M n b (g mol−1) | T on c (°C) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2a | CeCl3·7H2O | 650 | 500 | 260 | 42.1 |

| 2b | CeCl3·7H2O–NaI | 1300 | 2000 | 270 | 54.7 |

| 2c | CeCl3·7H2O–CuI | 600 | 400 | 270 | 45.8 |

| 2d | CeCl3·7H2O–KI | 100 | 350 | 261 | 45.6 |

1H-NMR analysis.

GPC analysis (detector RI, refractive index).

TGA analysis.

The NaI gave the optimal results, so then the ratio between CeCl3·7H2O and NaI was tested and an equimolar ratio allowed to reach the best result (Fig. S3,† CeCl3·7H2O : MxIy → 0.1 : 0.1 mol%).

The optimized catalytic procedure with CeCl3·7H2O–NaI was subsequently employed in melt-solid polycondensation,45,46 starting from oligolactic acid 2 (OLLA) and carrying out the polycondensation of OLLA in the presence of our CeCl3·7H2O–NaI catalytic system. Through a screening of the ratio between CeCl3·7H2O and NaI (Table 2) it was possible to prepare the aliphatic polyester with high molecular weight and with excellent conversions. The thermal dehydration without a catalyst did not result in a high molecular weight PLLA (Table 2, entry 2a). A high amount of CeCl3·7H2O–NaI (Table 2, entry 2f–h), was able to activate the dehydrative equilibrium. However, due to the hard reaction conditions, such a high concentration of the catalyst, relatively high temperature and long reaction time, induced l-lactide formation and relevant polymer decomposition rather than polycondensation. The results indicated in Table 2 entry 2c, show a weight average molecular weight of Mw = 48 300 g mol−1 as the highest molecular weight obtained in the melt polycondensation with a degree of polymerization (DP) equal to 1.08. This value was obtained after 7 h at 180 °C keeping pressure at 1333 Pascal and 0.7 wt% of CeCl3·7H2O. In Table 2 is also reported the onset degradation temperature (Ton) obtained from TGA. PLLA with the highest molecular weight showed a value around 300 °C (Table 2, entry 2c). Ton of the other polymers were lower except when the temperature of polymerization was 200 °C (Table 2, entry 2g). This behaviour could be explained considering all the degradation processes that might occur at high temperatures which led to the formation of shorter chains but also to the subsequent crosslinking of polymer matrixes. PLLA synthetized by melt polycondensation underwent a second step of Solid State Polymerization (SSP).

Optimization of the reaction conditions of the melt-solid state polymerization steps.

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Catalystb (wt%) | Temp. (°C) | Time (h) | M n c (g mol−1) | M w c (g mol−1) | T on d (°C) | Yielde (%) | DPc |

| 2a | — | 180 | 7 | 7500 | 8000 | 241 | 95 | 1.10 |

| 2b | 0.3 | 180 | 7 | 8000 | 8300 | 291 | 92 | 1.03 |

| 2c | 0.7 | 180 | 7 | 44 500 | 48 300 | 300 | 92 | 1.08 |

| 2d | 0.7 | 160 | 7 | 16 100 | 30 000 | 277 | 93 | 1.85 |

| 2e | 0.7 | 180 | 3 | 24 300 | 28 900 | 269 | 95 | 1.20 |

| 2f | 1.3 | 180 | 7 | 11 500 | 14 500 | 284 | 92 | 1.25 |

| 2g | 0.7 | 200 | 7 | 7300 | 33 700 | 306 | 79 | 4.70 |

| 2h | 0.7 | 180 | 14 | 16 500 | 29 900 | 281 | 93 | 1.81 |

| 2la | — | 150 | 16 | 52 400 | 94 500 | 305 | 92 | 1.80 |

| 2ma | — | 150 | 29 | 23 200 | 146 000 | 310 | 92 | 6.30 |

Solid state polymerization (SSP) starting from entry 2cMw = 48 300 Da.

Wt% of OLLA : CeCl3·7H2O : NaI (100 : 0.7 : 0.7).

GPC analysis (triple detector).

TGA analysis.

Yield (%) calculated by the equation yield = [g PLLA/g LLA] × 100.

In particular, PLLA with the highest Mw = 48 300 g mol−1 (Table 2, entry 2c), was then underwent the last step (Scheme 2), a solid state process, at 150 °C under reduced pressure. A further recrystallization with diethyl ether (Et2O) was carried out at room temperature. Kinetic studies were performed, after 16 h the PLLA 4 obtained reached an Mw = 94 500 g mol−1 with a DP value of 1.80 (Table 2, entry 2l) while, increasing to 29 h this value was equal to 6.30, due to an important decrease in Mn = 23 300 g mol−1, even if the Mw increases up to the value of Mw = 146 000 g mol−1 (Table 2, entry 2m) (Fig. S4†).

Scheme 2. Melt-solid state polymerization steps with m < n.

It was shown that the PLLA polymer synthesized by a two-step condensation polymerization of l-lactic acid in the presence of our CeCl3·7H2O–NaI system had significantly higher molecular weight and crystallinity as compared with PLLA produced with the conventional stannous-based catalyst. Discoloration was effectively inhibited by our cerium(iii) catalytic system, and there was no significant change in its Tg.

Ring opening polymerization of l,l-lactide (LA) catalyzed by CeCl3·7H2O–NaI system

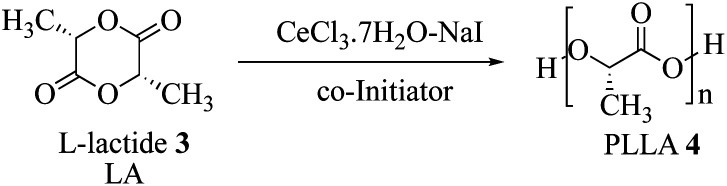

The poly(lactic acid) synthesis was also performed starting from l-lactide (LA) in order to verify the catalytic activity of the CeCl3·7H2O–NaI (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3. General ring opening polymerization reaction using CeCl3·7H2O–NaI system.

Following the previous study, we carried out the reaction in batch conditions comparing the only CeCl3·7H2O with the multimetallic system (0.1 mol%), without the need of any co-initiator, obtaining a better result with the second one, Mw = 11 500 Da and Mw = 15 300 respectively (Table 3), in 12 h at 165 °C.

Comparative study of cerium(iii) derivatives.

| Entry | Cat. | M n a (g mol−1) | M w a (g mol−1) | DPa | T on b (°C) | Conv.a (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3a | CeCl3·7H2O | 11 300 | 11 500 | 1.02 | 283 | 92 |

| 3b | CeCl3·7H2O–NaI | 12 700 | 15 300 | 1.20 | 287 | 97 |

GPC analysis (triple detector).

TGA analysis.

After the first trial with the combined system, a further screening of co-initiators was developed. As shown in Table 4 several alcohols were tested but the benzyl alcohol was the most promising with a Mw = 18 100 Da (Table 4, entry 4b), using 3 mol% for these first experiments.

Screening of several co-initiators.

| Entry | Co-init.a (mol%) | M n b (g mol−1) | M w b (g mol−1) | DPb | T on c (°C) | Conv.b (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4a | 1-Dodecanol | 4700 | 6700 | 1.40 | 273 | 96 |

| 4b | Benzyl alcohol | 16 700 | 18 100 | 1.20 | 283 | 93 |

| 4c | Ethylene glycol | 4700 | 8300 | 1.70 | 281 | 95 |

| 4d | 1,4-Butandiol | 1500 | 3300 | 2.10 | 274 | 94 |

3 mol% of co-initiator.

GPC analysis (triple detector).

TGA analysis.

A kinetic study was performed in order to ensure a good quality of the method and the best result was obtained after 12 h (Table S2†) at 165 °C even if other reaction temperatures were examined (160–170 °C).

In order to increase the reaction rate and make the whole process greener under an energetically perspective, we switched to microwaves.47–49 We maintained the same reaction conditions but the reaction time resulted to be reduced from 12 h to 1 h. The best upshot was reached after 1 h at 165 °C as shown in Table 5 entry 5b with an Mw = 24 500, (see kinetic studies in ESI, Fig. S5†).

Microwaves reaction screening with BnOH as co-initiator.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Temp. (°C) | M n a (g mol−1) | M w a (g mol−1) | T on b (°C) | Conv.a (%) |

| 5a | 160 | 8000 | 8200 | 250 | 91 |

| 5b | 165 | 23 400 | 24 500 | 274 | 96 |

| 5c | 170 | 15 000 | 15 300 | 255 | 94 |

GPC analysis (triple detector).

TGA analysis.

A further optimisation was performed in order to evaluate the ideal amount of the co-initiator, joint to the new catalytic system. The best reaction environment was obtained using 1.5 mol% of BnOH (Table 6, entry 6f).

Screening of catalyst and benzyl alcohol (BnOH) concentration.

| Entry | BnOH (mol%) | CeCl3·7H2O–NaIa (mol%) | M n b (g mol−1) | M w b (g mol−1) | T on c (°C) | Conv.b (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6a | 3 | — | 3500 | 3600 | 206 | 4 |

| 6b | 3 | 0.1 | 23 400 | 26 000 | 250 | 96 |

| 6c | 3 | 0.2 | 30 500 | 31 000 | 285 | 93 |

| 6d | 3 | 0.3 | 7000 | 7500 | 286 | 95 |

| 6e | — | 0.2 | 11 000 | 11 100 | 255 | 45 |

| 6f | 1.5 | 0.2 | 39 000 | 40 000 | 290 | 97 |

| 6g | 0.75 | 0.2 | 24 000 | 28 500 | 286 | 91 |

CeCl3.7H2O–NaI equimolar ratio.

GPC analysis (triple detector).

TGA analysis.

PLLA physico-chemical characterization

The structure is confirmed by a very useful information on the thermal stability of the present PLLA, provided by TGA, showing a very encouraging value and by FTIR-ATR spectrums, showing all characteristic peaks of poly(lactic acid) (Fig. S6 and S7†). The PLLA produced in this work has l-lactic acid (LA) stereoform, without the formation of other diastereoisomers. Thus, the formation of a mixture of polymers with different characteristics is avoided. By means of 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR spectrum, polymerization of LLA with CeCl3·7H2O–NaI system as catalyst at temperature ranging between 105–180 °C for 7 hours formed a polyester with PLLA configuration (ESI two-step synthesis, Fig. S8 and S9†). The quality of the polymer was given by GPC analysis (Fig. S10–S17†) which showed the formation of a linear polymer, with a truly low percentage of ramification, favouring suitable characteristics for further applications. Yield of PLLA are consistently high after two distinct steps and a ROP step synthesis. The highest yield of poly(lactic acid) was 97%, allowing to the formation of a great amount of polymer and without losing a significant amount of the starting material.50

Conclusions

The poly(lactic acid) synthesis has been optimised exploiting a cerium(iii) derivative coupled with NaI as novel catalytic system. The use of CeCl3·7H2O–NaI combination can be considered a very efficient catalytic system for the synthesis of poly-(l-lactic acid), for many reasons. First, its toxicity is extremely low compared to tin-based catalysts; second, the recycling process of PLA containing the cerium based catalyst would not represent a risk for the health due to its presence and concentration. Then, the synthetic methodology developed represents a further example of the importance of cerium salts application in the field of biomaterials. The known antibacterial properties of cerium ions, make them suitable for the production of biomaterials and PLA polymers as well as in our procedure. Our CeCl3·7H2O–NaI catalytic system, not only bypassed the problem of contamination from toxic metal catalysts, but its beneficial properties might be exploited for the bioactivity of the prepared biopolymers. Thus, it seems to be very reasonable to look for new efficient and eco-friendly catalysts. Indeed, the CeCl3·7H2O–NaI catalytic system allowed to obtain a PLLA with an intermediate molecular weight, which made the final polymer suitable for biomedical applications but to a less extent for mechanical ones. So, given the trend of a broadening of the spectrum of the PLA-based biomaterials with additional biological, physicochemical, or biomechanical properties, PLLA produced in these processes may be used for biomedical purposes such as drug delivery and for production of microcapsules. Further studies are in progress in our laboratories in order to link this biocompatible polyester with antimicrobial agents, antioxidants and drugs, for the use in medical fields.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contributions to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was carried out under the framework of the University Research Project ‘FAR2018: Fondo di Ateneo per la Ricerca’ supported by the University of Camerino. We thank for doctoral fellowships Fratelli Guzzini and ICA Group for grating doctoral fellowships to G. P., and A. M., respectively.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: XPS analysis, experimental details, NMR, FTIR GPC and TGA analysis, further optimization studies and kinetic informations. See DOI: 10.1039/d0ra10637b

Notes and references

- (a) Cadahve R. V. Vineeth S. K. Gadekar P. T. Open J. Polym. Chem. 2020;10:66–75. doi: 10.4236/ojpchem.2020.103004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (b) Corrêa H. L. Corrêa D. G. Front. Mater. 2020;7:283. doi: 10.3389/fmats.2020.00283. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Wang S. Urban M. W. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2020;5:562–583. doi: 10.1038/s41578-020-0202-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (b) Burattini S. Greenland B. W. Chappell D. Colquhoun H. M. Hayes W. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010;39:1973–1985. doi: 10.1039/B904502N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plota A. Masek A. Materials. 2020;13:4507. doi: 10.3390/ma13204507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biajoli A. F. P. Schwalm C. S. Limberger J. Claudino T. S. Monteiro A. L. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2014;25:2186–2214. [Google Scholar]

- Zarrintaji P. Jouyandeh M. Ganjali M. R. Sjirkavand B. Mozafari M. Sheiko S. S. Eur. Polym. J. 2019;117:402–423. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2019.05.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y. Daoud W. A. Cheuk K. K. L. Lin C. S. K. Materials. 2016;9:133. doi: 10.3390/ma9030133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G. Zhao M. Xu F. Yang B. Li X. Meng X. Teng L. Sun F. Li Y. Molecules. 2020;25:5023. doi: 10.3390/molecules25215023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon S. I. Lee C. W. Tanaguchi I. Miyamoto M. Kimura Y. Polymer. 2001;42:5059–5062. doi: 10.1016/S0032-3861(00)00889-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moon S. I. Taniguchi I. Miyamoto M. Kimura Y. Lee C. W. High Perform. Polym. 2001;13:5189–5196. doi: 10.1088/0954-0083/13/2/317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. W. Woo S. I. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2002;203:2245–2250. doi: 10.1002/1521-3935(200211)203:15<2245::AID-MACP2245>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steinborn-Rogulska I. Rokicki G. Polimery. 2013;58:85–92. doi: 10.14314/polimery.2013.085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ajioka M. Enomoto K. Suzuki K. Yamaguchi A. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1995;68:2125–2131. doi: 10.1246/bcsj.68.2125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Savioli Lopes M. Jardini A. Maciel Filho R. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2014;38:331–336. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A. Kumar V. Eur. Polym. J. 2007;43:4053–4074. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2007.06.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buchwalter P. Rosé J. Braunstein P. Chem. Rev. 2015;115:28–126. doi: 10.1021/cr500208k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garden J. A. Green Mater. 2017;5:103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Gruszka W. Lykkeberg A. Nichol G. S. Shaver M. P. Buchard A. garden J. A. Chem. Sci. 2020;11:11785–11790. doi: 10.1039/D0SC04705H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nys C. Van Regenmortal T. Janseen C. R. Oorts K. Smolders E. De Sehamphelaere K. A. C. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2018;37:623–642. doi: 10.1002/etc.4039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess F. Smarsly B. M. Over H. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020;53:380–389. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang S. Wang H. Cheu X. Li F. New Chem. Mater. 2005;33:66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Stierndahl A. Finne-Wistrand A. Albertsson A.-C. Bäckesjö C. M. Lindgren U. J. Biomed. Mater. Res., Part A. 2008;87:1086–1091. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahmayetty S. Prasetya B. Gozan M. Int. J. Appl. Eng. Res. 2015;10:41942–41946. [Google Scholar]

- Gruszka W. Lykkenberg A. Nichol G. S. Shaver M. P. Buchard A. Garden J. A. Chem. Sci. 2020;11:11785–11790. doi: 10.1039/D0SC04705H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The CeCl3·7H2O has the same toxicity level of NaCl, see: Imamoto T., Lanthanides in Organic Synthesis, Academic Press, New York, 1994 [Google Scholar]

- (a) Cortés I. Kaufman T. S. Bracca A. B. J. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018;5:180279. doi: 10.1098/rsos.180279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Properzi R. Marcantoni E. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014;43:779–791. doi: 10.1039/C3CS60220F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Bartoli G. Marcantoni E. Marcolini M. Sambri L. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:6104–6143. doi: 10.1021/cr100084g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Bartoli G. Bosco M. Giuliani A. Marcantoni E. Palmieri A. Petrini M. Sambri L. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:1290–1297. doi: 10.1021/jo035542o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bartoli G. Marcantoni E. Sambri L. Synlett. 2003;14:2101–2116. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-42098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoli G. Fernández-Bolaños J. G. Di Antonio G. Foglia G. Giuli S. Gunnella R. Mancinelli M. Marcantoni E. Paoletti M. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:6029–6036. doi: 10.1021/jo070384c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poryvaeva E. A. Egiazaryan T. A. Makarov V. M. Moskalev M. V. Razborov D. A. Fedyushkin I. L. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2017;53:346–352. doi: 10.1134/S1070428017030058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoli G. Bartolacci M. Giuliani A. Marcantoni E. Massaccesi M. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2005;14:2867–2879. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.200500038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoli G. Giuliani A. Marcantoni E. Massaccesi M. Melchiorre P. Lanari S. Sambri L. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2005;347:1673–1680. doi: 10.1002/adsc.200505184. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boatner L. A. Neal J. S. Ramey J. O. Chakoumakos B. C. Custelcean R. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013;103:141909. doi: 10.1063/1.4823707. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans W. J. Feldman J. D. Ziller J. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:4581–4584. doi: 10.1021/ja954276w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glinski J. Keller B. Legendziewicz J. Samela S. J. Mol. Struct. 2001;559:59–66. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2860(00)00687-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Narayau S. Muldoon J. Finn M. G. Fokin V. V. Kolb H. C. Sharpless K. B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:3275–3279. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiner C. M. Schreiner P. R. Chem. Commun. 2006;42:4315–4317. doi: 10.1039/B605850G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziano G. J. Chem. Phys. 2004;121:1878–1882. doi: 10.1063/1.1766291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egelhoff Jr W. E. Surf. Sci. Rep. 1986;6:253–415. doi: 10.1016/0167-5729(87)90007-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans J. W. Shreeve J. L. Ziller J. W. Doedens R. J. Inorg. Chem. 1995;34:576–585. doi: 10.1021/ic00107a009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Visser R. Dorenbos P. Andriessen J. van Eijk C. W. E. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 1993;5:5887–5910. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/5/32/017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park K.-H. Oh S.-J. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 1993;48:14833–14842. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.48.14833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnarsson O. Schonhammer K. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 1983;28:4315–4341. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.28.4315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- All the XPS spectra were taken after deposition of a homogeneous layer of the fine powdered samples of CeCl3·7H2O and CeCl3·7H2O–NaI, respectively, transferred onto a sample holder by means of a scotch tape. The photon source was the unmonochromatized Al Kα (hν = 1486.7 eV) line. The analyser is a VG-Clam 4 hemispherical analyser providing on overall resolution of 0.7 eV for a constant pass energy of 22 eV. All spectra have been aligned to the silica Si 2p core level (103.4 eV) in order to compensate charging of the samples. All measurements have been performed below 10−9 Torr.

- Molnár J. Konings R. J. M. Kolonits M. Hargittai M. J. Mol. Struct. 1996;375:223–229. doi: 10.1016/0022-2860(95)09093-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Espartero J. L. Rashkov I. Li S. M. Manolova N. Vert M. Macromolecules. 1996;29:3535–3539. doi: 10.1021/ma950529u. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moon S. I. Lee C. W. Taniguchi I. Miyamoto M. Kimura Y. Polymer. 2001;42:5059–5062. doi: 10.1016/S0032-3861(00)00889-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orozco V. H. Vargas A. F. Lopez B. L. Macromol. Symp. 2007;258:45–52. doi: 10.1002/masy.200751206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacotet-Navarro M. Rombaut N. Fabiano-Tixier A. S. Danguien M. Bily A. Chemat F. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2015;27:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2015.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirao K. Ohara H. Polym. Rev. 2011;51:1–22. doi: 10.1080/15583724.2010.537799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ju S. Green Process. Synth. 2016;5:1. [Google Scholar]

- Trathnigg B. Prog. Polym. Sci. 1995;20:615–650. doi: 10.1016/0079-6700(95)00005-Z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.