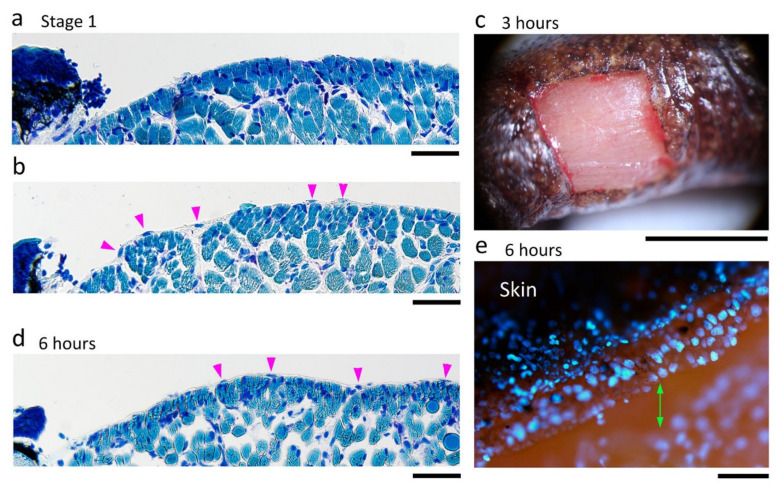

Figure 11.

Wound surface after the excision of full-thickness skin from the dorsal surface of the forearms. (a,b) Sample images showing the wound surface (i.e., the muscle layer) immediately after operation (Stage 1). These images were obtained from different animals. Wright-Giemsa stain. In this staining condition, cell nuclei were stained in dark blue, and muscle fibers were in light blue. On the other hand, connective tissues and blood capillaries were not stained. Therefore, the thickness of connective tissues or kinds of blood cells could be examined under Nomarski optics. In (a), the connective tissue (the epimysium) forming the surface of the muscle layer was mostly removed together with the skin, and therefore the muscle fibers were sometimes exposed to air. In (b), the epimysium remained. Arrowheads point to the nuclei of cells embedded in the epimysium. (c) Sample image of the wound surface at 3 h after operation. View under a dissecting microscope. Slight bleeding occurred along the wound margin but the blood immediately coagulated, leading to hemostasis. A thin membrane-like structure (possibly a fibrin membrane) covered the surface of the wound bed. (d) Representative image of the wound surface at 6 h after operation. In all 48 sections obtained from three forearms (16 sections each) whose wound surface suffered varying degrees of damage, the wound surface at 6 h was, as shown here, always smooth with the epimysium tissue, suggesting that the surface of the muscle layer repaired itself very quickly. In the repaired epimysium, nuclei were sometimes recognizable (arrowheads). (e) A view of the early wound epidermis (6 h after operation) from diagonally above. Cell nuclei were visualized by DAPI fluorescence. The wound epidermis at this stage extended, but was never attached, to the surface of the wound bed (double arrow). Scale bars: 100 μm (a,b,d,e); 2 mm (c).