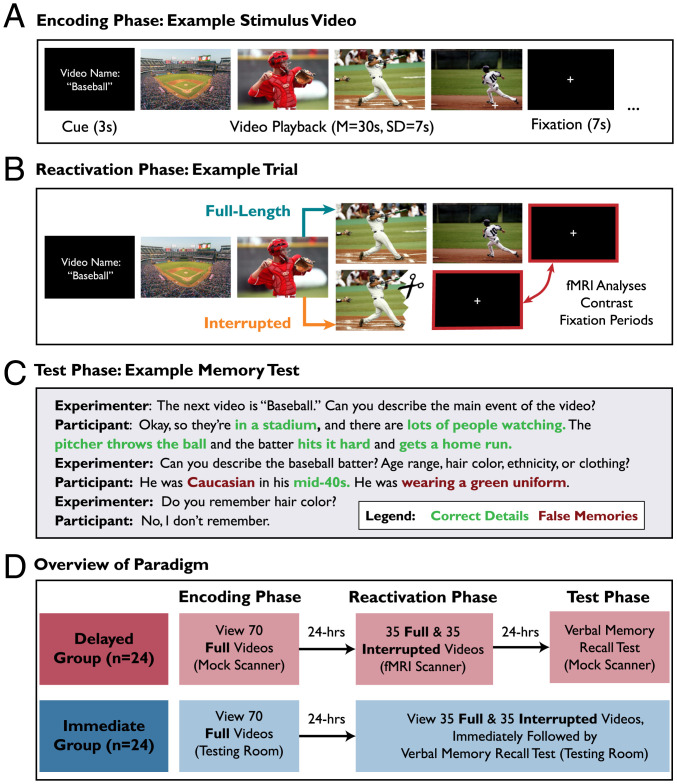

Fig. 1.

Overview of experimental paradigm. (A) During the encoding phase, all videos were presented in full-length form. Here we show example frames depicting a stimulus video. (B) During the reactivation phase, participants viewed the 70 videos again, but half (35 videos) were interrupted to elicit mnemonic prediction error. Participants were cued with the video name, watched the video (Full or Interrupted), and then viewed a fixation screen. The “baseball” video was interrupted when the batter was midswing. fMRI analyses focused on the postvideo fixation periods (red highlighted boxes). Thus, visual and auditory stimulation were matched across Full and Interrupted conditions, allowing us to compare postvideo neural activation while controlling for perceptual input. (C) During the test phase, participants answered structured interview questions about all 70 videos, and were instructed to answer based on their memory of the Full video originally shown during the Encoding phase. Here we show example text illustrating the memory test format and scoring of correct details (our measure of memory preservation) and false memories (our measure of memory updating, because false memories indicate that the memory has been modified). The void response (“I don’t remember”) is not counted as a false memory. (D) Overview of the experiment. All participants completed encoding, reactivation, and test phases of the study. The Delayed group (fMRI participants) completed the test phase 24 h after reactivation, because prior studies have shown that memory updating becomes evident only after a delay (e.g., to permit protein synthesis). The Immediate group completed the test phase immediately after reactivation and was not scanned. The purpose of the Immediate group was to test the behavioral prediction that memory updating required a delay.