Abstract

The SARS-CoV-2 vaccines have had an overwhelming success in curbing the COVID-19 global pandemic, accounting for countless lives saved. Adverse reactions are inevitable, given the vast scale of vaccination required to mitigate future surges of COVID-19. Hyperthyroid disorders have been reported as potential adverse reactions to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in two patients with Graves’ disease and a group of adults with subacute thyroiditis occurring in young women healthcare workers. We report a case of clinical Graves’ disease in a woman with a previously stable multinodular goitre that occurred 14 days following her second dose of Pfizer-BioNTech SARS-CoV-2 vaccine.

Keywords: COVID-19, thyroid disease, unwanted effects/adverse reactions, thyrotoxicosis

Background

To date, more than one billion people worldwide have been vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2. These vaccines have had overwhelming success in curbing the global COVID-19 pandemic. Adverse reactions are inevitable, given the vast scale of vaccination required to prevent seasonal surges of COVID-19. We are reporting a case of vaccine-induced Grave’s disease, an adverse reaction that has been reported in the literature twice following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination.

Case presentation

A 71-year-old woman with a history of stage 4 breast cancer in remission, struma ovarii at age 35 years and clinically stable multinodular goitre was admitted from the emergency department at a community hospital in Washington, DC, for new onset heart palpitations. She first noticed tachycardia 10 days prior to presentation due to her wearable fitness tracker. She reported feeling feverish in addition to new onset sweating, shortness of breath, leg swelling and dizziness and subsequently developed nausea, diarrhoea, abdominal pain and hand tremors. There was no documented upper respiratory tract infection prior to the onset of symptoms.

Pertinent initial findings were a resting pulse rate 111 beats per minute, blood pressure 125/74, temperature 37.8°C, respiratory rate 15 and O2 saturation 97% on room air. She was noted to be diaphoretic and mildly distressed but without observed ophthalmopathy initially. Her thyroid gland was diffusely enlarged to palpation. Cardiac examination was normal except for tachycardia. There was bilateral lower extremity oedema, extending halfway up the calves, with some tenderness in the left shin. She had a fine tremor on both hands.

Investigations

Initial laboratory testing showed relatively low white cell count 2.8×109/L, Absolute Neutrophil Count 1.4x109/L haemoglobin 87 g/L, platelet count 146x109/L, glucose 140 mg/dL and urea nitrogen 35 mg/dL. Haematological findings were long standing due to continued therapy for in-remission stage 4 breast cancer.

Thyroid function test revealed an undetectable Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (<0.01 µ(IU)/mL) and elevation in both free T4 to 7.2 ng/dL and total T3 to 5.3 ng/mL. The thyroid stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI) test was also high at 349%. Both thyroid peroxidase (TPO) and thyroglobulin (Tg) antibodies were negative. Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate was elevated to 126, from her previous baseline of 49. C-Reactive Protein was elevated to 6.9 (table 1). Electrocardiogram indicated sinus tachycardia. The patient had a negative nasal swab COVID-19 rapid RNA antigen test. Chest X-ray was normal. Thyroid ultrasound showed a stable multinodular disease. The patient has had multiple thyroid biopsies in the past all of which were negative for malignancy. Subsequently, she was transferred to an inpatient endocrine service in a community hospital in Maryland with a tentative diagnosis of thyroid storm.

Table 1.

Patient’s baseline, presentation and 1-month follow-up labs

| Investigation | Normal range | Baseline | Presentation | 1-month follow-up |

| Complete Blood Count | ||||

| Red cell count | 4.0–5.2 x1012/L | 3.37 | 2.66 | 3.22 |

| White cell count | 4.5–11.0x109/L | 2.46 | 2.77 | 2.80 |

| Haemoglobin | 120–150 g/L | 110 | 87 | 97 |

| Platelets | 150.0–350.0x109/L | 131 | 146 | 290 |

| Absolute Neutrophil Count | 1.5–7.80x109/L | 1.24 | 1.44 | 1.97 |

| Mean Corpuscular Volume | 80.0–100.0 fL | 100.3 | 96.6 | 95.0 |

| Complete Metabolic Panel | ||||

| Na | 135–143 mmol/L | 142 | 140 | 141 |

| K | 3.6–5.0 mmol/L | 4.6 | 4.1 | 4.6 |

| Cl | 98–107 mmol/L | 107 | 105 | 104 |

| HCO3 | 23–27 mmol/L | 30 | 24 | 26 |

| BUN | 7–20 mg/dL | 34 | 35 | 28 |

| Cr | 0.5–1.6 mg/dL | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.9 |

| Alb | 3.5–5.5 g/dL | 4.3 | 3.1 | 3.8 |

| Bili | <1.2 mg/dL | <0.2 | <0.2 | 0.4 |

| Alk phos | 33–147 µ(IU)/L | 79 | 64 | 80 |

| Aspartate Aminotransferase | 8–33 U/L | 15 | 18 | 14 |

| Alanine Transaminase | 7–55 U/L | 11 | 20 | 25 |

| Glucose | 71–99 mg/dL | 91 | 149 | 112 |

| Additional studies | ||||

| Brain Natriuretic Peptide | 20–127 pg/mL | 194 | 356 | 248 |

| Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate | 0–30 mm/hour | 49 | 126 | 108 |

| C-Reactive Protein | 0.15–5.0 mg/L | 2.4 | 6.9 | 2.3 |

| Thyroid studies | ||||

| Thyroid Stimulating Hormone | 0.35–2.00 µ(IU)/mL | 1.18 | <0.02 | <0.02 |

| Free T4 | 0.9–1.7 ng/dL | 1.4 | 7.2 | 1.3 |

| Total T3 | 0.8–2.8 ng/mL | 1.1 | 5.3 | 1.3 |

| Thyroid stimulating immunoglobulin | <140% baseline | – | 347 | 438 |

| Thyroid peroxidase | 0–9.0 IU/mL | – | 8.9 | 8.6 |

– shows lab value was not obtained or no value was available per patient records.

The temporal sequence of events 2 weeks after the second dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is highly indicative of a vaccine-induced Graves’ disease. The patient progressed from biochemically normal thyroid function and histologically normal multinodular at baseline to clinical thyroid storm after vaccination. Thyroid storm was associated with undetectable TSH, high free T4, high total T3, negative TPO and Tg antibodies and a rapid rise in TSI.

Differential diagnosis

The development of both clinical and biochemical hyperthyroidism with elevated acute inflammatory markers in a patient with a history of euthyroid multinodular goitre 2 weeks after administration of the vaccine makes vaccine-induced autoimmune syndrome the most likely explanation of our patient’s presentation and symptoms. The patient’s clinical manifestations suggest vaccine-induced Graves’ disease, especially in the context of diffusely enlarged thyroid glands and an associated elevated TSI. Viral-induced subacute thyroiditis is another potential cause of the patient’s hyperthyroid state, but the patient did not have a preceding viral infection. In addition, the patient responded appropriately to the antithyroid drug methimazole and did not become rapidly and profoundly hypothyroid as would be expected in viral subacute thyroiditis. Furthermore, hashitoxicosis is also an unlikely diagnosis in someone with the above presentation and negative TPO and Tg antibodies at baseline. In light of the clinical and biochemical findings and the temporal sequence of events following the vaccine, the most likely explanation of our patient’s presentation is a vaccine-induced Graves’ disease.

Treatment

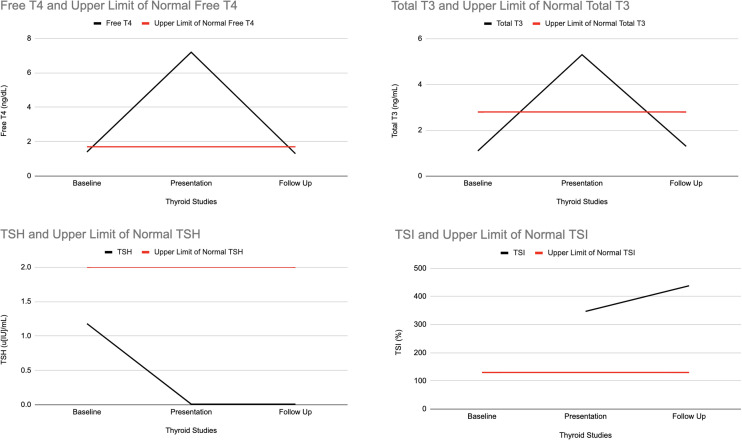

The patient was successfully treated with methimazole 20 mg two times per day and atenolol 25 mg daily with continued cardiac monitoring while in the hospital. With this regimen, her symptoms and biochemical profile began to improve significantly. At hospital discharge, her free T4 had fallen to 3.8 µg/dL and total T3 had fallen to 4.1 ng/mL (figure 1). She reported no side effects of either medication and was discharged from the hospital on this treatment regimen and was recommended to follow-up with both endocrinology and ophthalmology. She continued to have appropriate medication dose adjustments at follow-up visits and is being monitored clinically and biochemically for resolution of her symptoms and normalisation of thyroid function.

Figure 1.

Thyroid function over time. TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone. TSI, thyroid stimulating immunoglobulin.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient has experienced a significant improvement in her symptoms. She is now clinically stable. She is being carefully monitored by an endocrinologist for management of probable Graves’ disease. She is also being followed by an ophthalmologist for Graves’ ophthalmopathy, which was classified as moderate to severe 10 weeks following her hospitalisation. The patient has reported resolved tachycardia and her FT4 and total T3 levels have returned to baseline. Thyroid Stimulating Hormone normalisation is lagging behind and thus remains undetectable. It is important to note that the patient has not experienced any hypothyroid symptoms since her hospitalisation, making a retrospective diagnosis of subacute thyroiditis unlikely.

Discussion

Emergency authorisation was granted for the Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine on 11 December 2020. Common side effects of the vaccine reported in the clinical trial were pain, redness and swelling at the injection site, as well as constitutional symptoms such as fatigue, fever, headache and myalgia.1 Four cases of Graves’ disease have been reported following the Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine in two women and one man with no previous thyroid history and another case in a woman with a history of Graves’ disease who had been euthyroid for many years following successful treatment.2 3 Our patient’s clinical and biochemical presentation further adds to the growing body of evidence that the Pfizer-BioNTech SARS-CoV-2 vaccine may be associated with the incidence of Graves’ disease in some patients.

Thyrotoxicosis is a disorder of excessive thyroid hormone. Patients present with symptoms of increased sympathetic autonomic activity and metabolic rate. Two common causes of ‘overproducing’ thyrotoxicosis are autonomous production of thyroid hormone by a single or multiple thyroid adenomas or Graves’ disease as in the case in our patient.4 Another cause of thyrotoxicosis is subacute thyroiditis, which is a self-limiting inflammatory condition of the thyroid that presents 3–8 weeks following viral upper respiratory tract infections, including COVID-19.5–8 After the hyperthyroid phase of subacute thyroiditis, patients can either return to a euthyroid state within a few weeks or present with a transient hypothyroidism prior to achieving their baseline euthyroid levels. Although a thyroid uptake and scan study is considered the gold standard test in confirming the diagnosis of Graves’, this test was not ordered for our patient. Nonetheless, the combination of clinical and biochemical presentation, improvement of FT4 and TT3 hormone levels with methimazole, development of ophthalmopathy and absence of hypothyroid symptoms strongly support the diagnosis of Graves’ disease.

Although the pathogenesis of thyroiditis has not been fully elucidated, one proposed mechanism involves cytotoxic T-lymphocyte activation in response to antigen bound complexes that results in damage of the thyroid follicles due to cross reactivity between the viral antigen and thyroid tissue.8 Further, both subacute thyroiditis and Graves’ disease have each been associated with specific human leucocyte antigens (HLA).4 9 In genetically susceptible individuals, hyperthyroidism may occur due to the molecular mimicry between the HLA and virus, where HLA serves as a receptor for pathogen entry or viral products are altering the HLA structure or function.9

The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine is a two-dose vaccine composed of a nucleoside mRNA that encodes for the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein which subsequently is surrounded by lipid nanoparticles. Polyethylene glycol—an adjuvant employed in the development of the lipid nanoparticle of the vaccine—has previously been implicated in allergic reactions following delivery of medications and other vaccines.10 Autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants (AISA) refers to the acute manifestation of immune-mediated symptoms in a previously healthy individual following exposure to an external stimulus.9

Our patient meets the diagnostic criteria for AISA given temporal development of an autoimmune thyroid condition post vaccination. AISA has been identified as an adverse effect following a number of other vaccinations, including the hepatitis A, influenza and tetanus toxoid vaccine among others.11 Thyroid-manifested AISA was also identified in two patients following administration of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine; however, unlike our patient, both of these women fell within the expected age range often associated with the onset of autoimmune disorders.2 Thyroid-manifested AISA was also identified in four patients following administration of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine; however, unlike our patient, three of these cases fell within the expected age range often associated with the onset of autoimmune disorders and the other presented in a similarly aged patient who was previously diagnosed and treated for Graves’ disease.2 3 In all cases where a serum TSH level was measured at presentation, it was suppressed with a concurrent rise in serum free T3 and serum T4 (table 2). The onset of symptoms was also similar between patients, with all cases occurring within 7 weeks following vaccination with either their first or second vaccination dose. Notably, all five patients were appropriately treated and experienced relief of their presenting hyperthyroid symptoms. Only our patient has reported disease sequelae on follow-up, developing Graves’ ophthalmopathy in the months that followed her hospitalisation.

Table 2.

Baseline biochemical profile of the five patients who developed Graves’s disease following vaccination against SARS-CoV-2

| Investigation | Patient 17 | Patient 27 | Patient 38 | Patient 48 | Patient 5 | Reference range |

| 40-year-old woman | 28-year-old woman | 71-year-old woman | 46-year-old man | 71-year-old woman (case presentation) | ||

| Thyroid Stimulating Hormone | <0.001 | <0.001 | – | – | <0.02 | 0.35–2.00 µ(IU)/mL |

| Free T4 | 3.57 | 1.84 | 3.56 | 1.63 | 7.2 | 0.9–1.7 ng/dL |

| Total T3 | 251 | 216 | 11.10 | – | – | 0.8–2.8 ng/mL |

| Free T3 | 10.5 | 9.2 | – | 5.18 | 5.30 | 2.02–4.4 pg/mL |

| Anti-TSH receptor Antibodies | 16.56 | 5.85 | 4.2 | 2.9 | – | 0–1.75 UI/L |

| Thyroid stimulating immunoglobulin | 380 | – | – | – | 347 | <140% baseline |

– shows lab value was not obtained or no value was available per patient records.

A recent study that sought to further understand cross reactivity between SARS-CoV-2 and human tissues found that the viral spike protein, nucleoprotein and membrane protein cross react with TPO.12 This cross reactivity serves as a plausible explanation for the presentation of thyrotoxicosis following administration of the vaccine. We do not have information on specific HLA subtypes in our patient; however, the presence of HLA antigens implicated in disorders of hyperthyroidism could have further compounded the effect of molecular mimicry leading to an autoimmune response.

Our patient adds the fifth reported case to the medical literature of patients developing Graves’ disease shortly after receiving the two-dose Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. Our patient was an elderly woman with a stable, euthyroid multinodular goitre. The previously reported case involved two young women who worked in healthcare. The two-dose scheduling of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine is optimised to strengthen and reinforce the immunological response to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. In doing so, the second dose boosts the immune system to its peak capacity, thus making some patients susceptible to cross-autoimmune reactions. As a result, our case highlights the importance of closely observing patients after vaccination against COVID-19—as Graves’ disease can occur and present with severe symptoms of thyrotoxicosis. Immediate correct diagnosis and treatment are essential in preventing threatening comorbidities of Graves’ disease such as ophthalmopathy and thyroid storm.

Learning points.

Be cognizant of post COVID-19 vaccine immunological reactions including hyperthyroidism.

Look for symptoms of Graves’ disease in the weeks following vaccination against COVID-19, even if a patient has no predisposing risk factors; prompt identification and treatment can prevent significant comorbid sequelae.

Importance of counselling patients prior to receiving the vaccine as they may experience thyroid-related side effects, even in those without previous history of thyroid disorders.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patient for her contributions and feedback throughout the drafting and submission process.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors: contributed equally to the case report, data analysis and interpretation of data. TJG, AEP and AJM: planning, conception and design and data acquisition. AJM: cared for the patient. GT: critically reviewed the case report.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Case reports provide a valuable learning resource for the scientific community and can indicate areas of interest for future research. They should not be used in isolation to guide treatment choices or public health policy.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s).

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine overview and safety. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/different-vaccines/Pfizer-BioNTech.html [Accessed 23 Jun 2021].

- 2.Vera-Lastra O, Ordinola Navarro A, Cruz Domiguez MP, et al. Two cases of Graves' disease following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: an Autoimmune/Inflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants. Thyroid 2021;31:1436–9. 10.1089/thy.2021.0142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zettinig G, Krebs M. Two further cases of Graves' disease following SARS-Cov-2 vaccination. J Endocrinol Invest 2021. 10.1007/s40618-021-01650-0. [Epub ahead of print: 03 Aug 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Franklyn JA, Boelaert K. Thyrotoxicosis. Lancet 2012;379:1155–66. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60782-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mattar SAM, Koh SJQ, Rama Chandran S, et al. Subacute thyroiditis associated with COVID-19. BMJ Case Rep 2020;13:e237336. 10.1136/bcr-2020-237336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khatri A, Charlap E, Kim A. Subacute thyroiditis from COVID-19 infection: a case report and review of literature. Eur Thyroid J 2021;9:324–8. 10.1159/000511872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brancatella A, Ricci D, Viola N, et al. Subacute thyroiditis after Sars-COV-2 infection. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020;105:2367–70. 10.1210/clinem/dgaa276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Desailloud R, Hober D. Viruses and thyroiditis: an update. Virol J 2009;6:5. 10.1186/1743-422X-6-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohsako N, Tamai H, Sudo T, et al. Clinical characteristics of subacute thyroiditis classified according to human leukocyte antigen typing. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1995;80:3653–6. 10.1210/jcem.80.12.8530615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kounis NG, Koniari I, de Gregorio C, et al. Allergic reactions to current available COVID-19 vaccinations: pathophysiology, causality, and therapeutic considerations. Vaccines 2021;9:221. 10.3390/vaccines9030221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perricone C, Colafrancesco S, Mazor RD, et al. Autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants (ASIA) 2013: unveiling the pathogenic, clinical and diagnostic aspects. J Autoimmun 2013;47:1–16. 10.1016/j.jaut.2013.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vojdani A, Vojdani E, Kharrazian D. Reaction of human monoclonal antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 proteins with tissue antigens: implications for autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol 2021;11:617089. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.617089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]