BACKGROUND:

On average, a person living in San Francisco can expect to live 83 years. This number conceals significant variation by sex, race, and place of residence. We examined deaths and area-based social factors by San Francisco neighborhood, hypothesizing that socially disadvantaged neighborhoods shoulder a disproportionate mortality burden across generations, especially deaths attributable to violence and chronic disease. These data will inform targeted interventions and guide further research into effective solutions for San Francisco’s marginalized communities.

STUDY DESIGN:

The San Francisco Department of Public Health provided data for the 2010–2014 top 20 causes of premature death by San Francisco neighborhood. Population-level demographic data were obtained from the US American Community Survey 2015 5-year estimate (2011–2015). The primary outcome was the association between years of life loss (YLL) and adjusted years of life lost (AYLL) for the top 20 causes of death in San Francisco and select social factors by neighborhood via linear regression analysis and heatmaps.

RESULTS:

The top 20 causes accounted for N = 15,687 San Francisco resident deaths from 2010–2014. Eight neighborhoods (21.0%) accounted for 47.9% of city-wide YLLs, with 6 falling below the city-wide median household income and many having a higher percent population Black, and lower education and higher unemployment levels. For chronic diseases and homicides, AYLLs increased as a neighborhood’s percent Black, below poverty level, unemployment, and below high school education increased.

CONCLUSIONS:

Our study highlights the mortality inequity burdening socially disadvantaged San Francisco neighborhoods, which align with areas subjected to historical discriminatory policies like redlining. These data emphasize the need to address past injustices and move toward equal access to wealth and health for all San Franciscans.

Death attributable to homicide and chronic disease is associated with increased neighborhood percent Black, below poverty line, unemployment, and below high school education. This mortality inequity burdening people in socially disadvantaged San Francisco neighborhoods aligns with areas subjected to historical discriminatory policies, such as redlining.

Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Health disparities exist worldwide and are a persistent crisis within American communities.1,2 Specifically, health outcomes are worse in historically marginalized or excluded groups based on sex, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and other social characteristics.3,4 There has been widespread recognition of the complex effects and interactions that area-based social determinants of health (SDoH) exert on individual health,5,6 where SDoH denote “employment, income, housing, transportation, child care, education, discrimination, and the quality of the places where people live, work, learn, and play, which influence health.”3 Disadvantaged communities are frequently characterized by a lack of opportunity, discrimination, violence, limited access to critical services, and inequality.7,8 All of these factors contribute to chronic stress that can act as an added mediator to worse health outcomes.8

Evidence shows that neighborhoods do not form spontaneously. Many are rooted in structural racism propagated by federally discriminatory policies like “redlining,” where areas with racial minority residents were labeled as high risk for lending by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, leading to longstanding inequities in wealth and opportunity across generations that are extremely difficult to overcome.3,9,10 The connections between poor health and inequality are clear,8 as is the distinctly unequal opportunity to escape disadvantage given the strong link between an individual’s odds for upward mobility and living in areas with less income inequality, less residential segregation, greater social capital and family stability, and better primary schools.11 We have also come to appreciate the multifaceted relationship between health and disease and that population health is not only the sum of individual risks.12,13 Understanding the complex contributions of economic, societal, and biologic factors to diseases and location-related mortality disparities is essential to eradicating them.13 Although past studies have explored these disparities,14,15 an examination of the burden of premature deaths, area-based social factors, and historical discrimination at the neighborhood level remains understudied.

In 2017, a person living in San Francisco could expect to live around 83 years. This number conceals significant variation not only by sex and race, but also based on where one lives. Data from 2012 through 2016 indicate that a person living in the Tenderloin neighborhood could expect to live 73.7 years, whereas a person in Twin Peaks may live 93.6 years.14 To further explore this disparity, we sought to examine premature deaths and various area-based social factors at the neighborhood level in the city of San Francisco. We hypothesized that populations living in socially disadvantaged neighborhoods shoulder a disproportionate burden of deaths, with deaths attributable to chronic disease and violence going hand in hand, with younger populations and multiple generations affected, creating a lack of wealth/health trap that is difficult to overcome. We also hypothesized that there would be overlap between the most affected neighborhoods today and areas impacted by historical discriminatory policies. These data will shed light on the proximate causes of persistent downstream health disparities affecting our San Francisco communities, providing evidence-based targets for cross-sectoral interventions and further research into effective solutions that enable every San Franciscan the same opportunity for health and wealth.

METHODS

IBR approval was not required owing to the data being deidentified and/or publicly available. This is an epidemiologic, ecological, cross-sectional study using group-level data.

Data

San Francisco death data for years 2010 through 2014 at the neighborhood level were provided by the San Francisco Department of Public Health (SFDPH) in Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA), originating from the California Department of Public Health (CDPH). Deaths were mapped using a sequence of geocoding methods, including the San Francisco Emergency Alert System service (over 90% of deaths mapped in first pass, gold standard in San Francisco), Google Maps, latitude and longitude provided by the CDPH, or manually. Provided measures for the top 20 causes of premature death citywide, based on years of life lost (YLL), included cause of death counts, YLL, adjusted years of life lost (AYLL), and average years of life lost stratified by neighborhood. YLL calculations were based on the 2000–2011 World Health Organization Standard Life Table, and standard population weights were calculated from the US 2000 standard population. American Community Survey (ACS) data were used for population denominators. Adjusted YLL were age-adjusted and standardized to the 2000 population and annualized. Methods for these calculations have previously been described.15

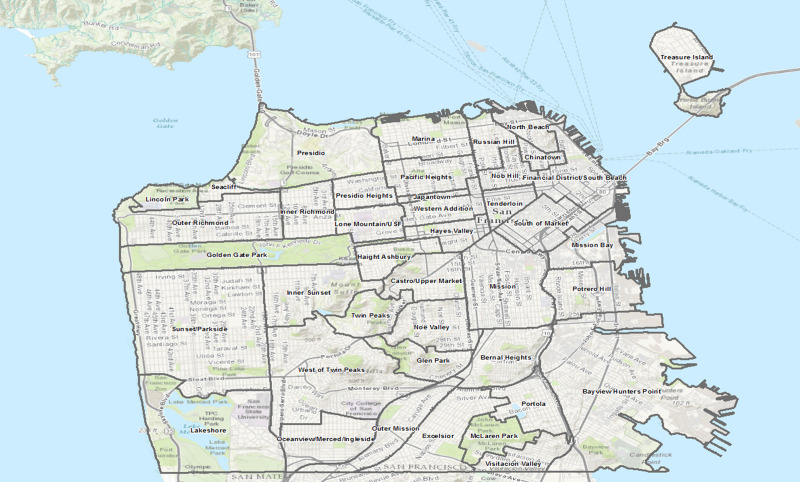

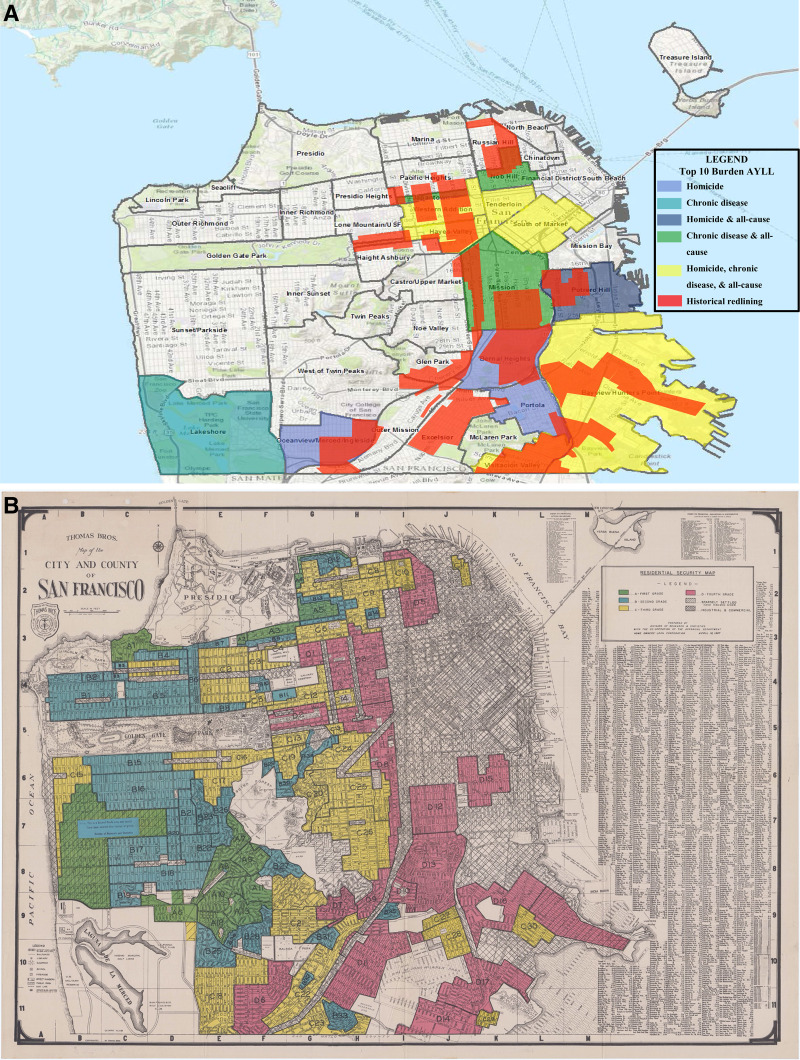

Population-level demographic data were obtained from the ACS 5-year estimate for 2015 (includes years 2011 through 2015). Variables assessed included age, sex, race/ethnicity, education level, employment status, median household income (MHI), and percent below poverty level (PBPL). SFDPH mapped census tracts to San Francisco neighborhoods (Fig. 1) using the census tract neighborhood crosswalk 2010, and census data were averaged across census tracts at the neighborhood level in Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA).

Figure 1.

Map of San Francisco neighborhoods. Image provided courtesy of the San Francisco Department of Public Health

Statistical analysis

The main outcomes of interest were the burden of AYLLs for the top 20 causes of death by San Francisco neighborhood, and the association between AYLLs and select social factors at the neighborhood level, with a specific focus on chronic diseases and violence. Homicide (assault) deaths were used as an indicator of violence. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention define chronic diseases as “conditions that last 1 year or more and require ongoing medical attention or limit activities of daily living or both.”16 The chronic disease category included: ischemic heart diseases, cerebrovascular disease, hypertensive disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, cancer (lung/trachea/bronchial, colon/rectal, liver, pancreas, breast, lymphoma/multiple myeloma), dementia/Alzheimer’s, diabetes mellitus, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and drug and alcohol use disorders. Golden Gate Park, Lincoln Park, and McLaren Park were excluded from analysis because they are parks vs neighborhoods and their YLL and AYLL were likely affected by low populations and death counts. Eighteen (0.11%) deaths were excluded. There were N = 109 (0.69%) deaths that could not be geocoded to place of residence and were removed from the neighborhood-level analysis. All deaths were included in citywide calculations.

Median AYLL and interquartile ranges by cause of death were calculated across neighborhoods and graphed using Stata/SE 15 for Mac (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Univariable linear regression analysis was performed to assess the association between select neighborhood social factors and AYLLs for each of the top 20 causes of death in San Francisco, as well as chronic diseases and total AYLLs. Independent variables included PBPL, percent population unemployed, percent population under 60 years of age, percent population male, percent population Black, and percent population with less than a high school education. Changes in y were scaled to standard deviations of x.

We also sought to explore the overlap between present-day neighborhoods with the highest AYLLs and areas subjected to historical discriminatory housing practices or “redlining,” which was mapped using PowerPoint (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). The 1937 City and County of San Francisco Home Owner’s Loan Corporation (HOLC) Residential Security Map17 was used to inform boundaries of previously “redlined” or D - fourth grade areas at the street level for transcription to a map of current San Francisco neighborhoods. If any portion of a current San Francisco neighborhood had an area of red it was considered historically redlined.

RESULTS

Citywide demographics

San Francisco had 840,763 residents according to the 2015 5-year ACS. Most identified as White (48.73%) or Asian (33.83%), followed by Latinx any race (15.30%), Black (5.57%), two races (4.63%), Asian Pacific Islander (0.43%), or American Indian or Alaska Native (0.34%). Highest achieved education levels varied widely across the city for those aged 25 years and older, with most having a Bachelor’s degree or higher (54.02%), followed by 20.31% with some college or associate’s degree, 12.93% with less than a high school diploma, and 12.61% with a high school diploma. For the civilian labor force 16 years and older, 6.65% were unemployed. Citywide MHI was $81,953, and the PBPL was 13.24%. Additional demographics at the neighborhood level are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

San Francisco Neighborhood Social Factors

| Neighborhood∗ | Population, n | Sex m, % | Age <60 y, % | Race/ethnicity, Black, % | Education, less than HS, %† | Unemployed, %† | MHI, $ | PBPL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinatown | 14,336 | 48.99 | 64.17 | 0.75 | 52.25‡ | 8.86‡ | 20,508.74§ | 29.87‡‖ |

| Tenderloin | 28,820 | 61.30 | 78.52 | 9.81‡ | 23.67‡ | 8.40‡ | 21,863.07§ | 31.67‡‖ |

| SoMa | 18,093 | 56.15 | 76.01 | 12.28‡ | 17.33‡ | 6.22 | 39,761.31§ | 27.16‡‖ |

| Treasure Island | 3,187 | 53.84 | 95.36 | 18.61‡ | 10.92 | 12.14‡ | 40,740.74§ | 51.84‡‖ |

| Lakeshore | 13,469 | 47.19 | 85.08 | 6.77‡ | 6.79 | 12.36‡ | 48,057.85§ | 32.40‡‖ |

| Visitacion Valley | 17,793 | 48.05 | 79.81 | 13.06‡ | 28.32‡ | 13.78‡ | 49,394.98§ | 18.09‡ |

| Bayview/Hunters Point | 37,246 | 48.85 | 84.31 | 27.66‡ | 26.08‡ | 12.50‡ | 52,430.94§ | 21.75‡‖ |

| Western Addition | 21,366 | 48.69 | 72.61 | 20.34‡ | 9.61 | 8.16‡ | 54,446.53§ | 19.22‡ |

| Japantown | 3,633 | 43.41 | 57.64 | 5.64‡ | 11.08 | 5.12 | 62,647.06§ | 19.17‡ |

| Nob Hill | 26,382 | 51.53 | 79.52 | 2.92 | 11.94 | 4.63 | 63,184.43§ | 15.95‡ |

| Excelsior | 39,640 | 50.84 | 78.98 | 2.38 | 24.22‡ | 8.88‡ | 67,659.03§ | 9.52 |

| Outer Richmond | 45,120 | 48.14 | 74.72 | 1.79 | 12.32 | 4.57 | 69,897.40§ | 10.18 |

| Oceanview | 28,261 | 49.36 | 78.88 | 13.53‡ | 21.93‡ | 11.51‡ | 70,546.38§ | 15.34‡ |

| Portola | 16,269 | 48.22 | 76.96 | 4.53 | 29.61‡ | 6.72‡ | 74,589.25§ | 12.69 |

| North Beach | 12,550 | 54.43 | 75.57 | 0.93 | 10.36 | 6.70‡ | 74,777.45§ | 14.98‡ |

| Outer Mission | 23,983 | 48.05 | 78.40 | 1.29 | 19.20‡ | 8.33‡ | 76,383.87§ | 8.93 |

| Mission | 57,873 | 56.00 | 83.30 | 3.06 | 16.51‡ | 7.38‡ | 77,526.79§ | 15.80‡ |

| Inner Richmond | 22,425 | 47.79 | 78.07 | 2.02 | 10.68 | 6.20 | 78,530.81§ | 14.02‡ |

| Hayes Valley | 18,043 | 59.68 | 87.71 | 13.44‡ | 6.21 | 4.65 | 82,195.19 | 12.66 |

| Sunset/Parkside | 80,525 | 47.59 | 75.41 | 0.83 | 14.24‡ | 6.44 | 84,652.72 | 10.08 |

| Lone Mountain/USF | 17,434 | 46.46 | 85.09 | 6.86‡ | 5.89 | 6.02 | 86,388.04 | 11.77 |

| Twin Peaks | 7,310 | 59.66 | 74.60 | 4.30 | 2.92 | 3.44 | 89,896.80 | 5.25 |

| Bernal Heights | 25,487 | 51.07 | 84.14 | 4.88 | 10.59 | 8.46‡ | 98,285.80 | 9.20 |

| Inner Sunset | 28,962 | 48.04 | 80.50 | 1.94 | 6.10 | 3.97 | 101,763.75 | 9.24 |

| Mission Bay | 9,979 | 53.81 | 91.91 | 5.10 | 4.20 | 4.89 | 106,508.88 | 13.51‡ |

| Russian Hill | 18,179 | 47.50 | 76.97 | 0.93 | 8.84 | 2.20 | 107,953.48 | 8.75 |

| Glen Park | 8,119 | 51.99 | 76.78 | 6.40‡ | 3.79 | 5.23 | 115,550.85 | 8.36 |

| FiDi/South Beach | 16,735 | 52.67 | 81.90 | 1.85 | 5.75 | 5.93 | 117,239.54 | 11.95 |

| Presidio Heights | 10,577 | 45.55 | 79.59 | 2.51 | 4.63 | 7.32‡ | 117,532.73 | 8.32 |

| Pacific Heights | 24,737 | 48.51 | 78.60 | 3.24 | 2.24 | 3.76 | 117,699.39 | 6.56 |

| Haight Ashbury | 17,758 | 53.93 | 87.98 | 3.10 | 2.14 | 5.15 | 119,121.06 | 9.45 |

| Castro/Upper Market | 20,380 | 63.00 | 82.31 | 2.92 | 2.54 | 4.09 | 120,645.31 | 7.11 |

| Marina | 24,915 | 46.42 | 84.87 | 1.01 | 2.52 | 4.87 | 123,461.93 | 5.85 |

| Noe Valley | 22,769 | 50.40 | 83.34 | 2.85 | 2.84 | 5.09 | 126,117.02 | 5.66 |

| West of Twin Peaks | 37,327 | 50.64 | 74.17 | 3.27 | 5.68 | 5.42 | 126,595.13 | 6.28 |

| Seacliff | 2,491 | 46.13 | 74.59 | 0.52 | 2.04 | 5.01 | 143,506.49 | 7.31 |

| Potrero Hill | 13,621 | 52.32 | 88.62 | 5.59‡ | 4.58 | 6.20 | 147,671.10 | 9.69 |

| Presidio | 3,681 | 51.24 | 98.48 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.27 | 161,615.04 | 4.11 |

| All¶ | 840,763 | 50.89 | 79.81 | 5.57 | 12.93 | 6.65 | 81,953.04 | 13.24 |

Ordered by increasing median household income.

Denominator, population categories provided by US Census American Community Survey.

More than citywide level.

Below citywide level.

More than 20% PBPL, federal definition of poverty area.18

Including all people living in San Francisco.

FiDi, Financial District; HS, high school; MHI, median household income; PBPL, percent below poverty level; SoMa, South of Market; USF, University of San Francisco

Citywide deaths

From 2010 through 2014, the top 20 causes of death in San Francisco based on YLL accounted for N = 15,687 resident deaths, contributing a total of 211,662 YLL and 4,381.32 AYLL (Table 2). Top causes of death by AYLL are shown in Table 3. The highest average YLLs by cause of death included homicide (26.15 years), drug use disorders (22.89), suicide (22.86), HIV (22.11), and alcohol-attributable diseases and disorders (21.34). During the study period there were N = 206 homicides, contributing 5,387.43 (2.5%) YLL and ranking 18th based on AYLL (125.86) yet first for average YLL per death. There were N = 14,231 deaths attributable to chronic diseases (90.7% of all deaths), accounting for 186,424.88 (88.1%) YLL, 3,828.79 AYLL, and 13.10 average YLL per death.

Table 2.

Expected Years of Life Lost (YLL) and Age-Adjusted YLL (AYLL) for Top 20 Causes of Death by San Francisco Neighborhood, 2010–2014

| Neighborhood∗ | Deaths, n | YLL | YLL %† | Average YLL‡ | AYLL§ | AYLL ratio‖ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinatown | 592 | 6,499.54 | 3.1 | 10.98 | 4458.40 | 1.4 |

| Tenderloin¶ | 1029 | 17,956.07 | 8.5 | 17.45 | 9995.56 | 3.1 |

| SoMa¶ | 638 | 10,099.42 | 4.8 | 15.83 | 8546.52 | 2.7 |

| Treasure Island | 14 | 341.14 | 0.2 | 24.37 | 2986.68 | 0.9 |

| Lakeshore | 176 | 2,644.27 | 1.2 | 15.02 | 4658.98 | 1.4 |

| Visitacion Valley | 387 | 5,447.82 | 2.6 | 14.08 | 5741.27 | 1.7 |

| Bayview/Hunters Point¶ | 797 | 12,174.00 | 5.7 | 15.27 | 6947.49 | 2.2 |

| Western Addition | 552 | 7,428.04 | 3.5 | 13.46 | 5432.32 | 1.7 |

| Japantown | 99 | 1,198.09 | 0.6 | 12.10 | 4858.79 | 1.5 |

| Nob Hill | 549 | 7,304.21 | 3.4 | 13.30 | 4988.00 | 1.5 |

| Excelsior¶ | 696 | 8,911.68 | 4.2 | 12.80 | 3970.62 | 1.3 |

| Outer Richmond¶ | 943 | 11,108.18 | 5.2 | 11.78 | 3592.07 | 1.1 |

| Ocean View | 513 | 6,995.76 | 3.3 | 13.64 | 4235.82 | 1.3 |

| Portola | 345 | 4,373.74 | 2.1 | 12.68 | 4580.13 | 1.4 |

| North Beach | 281 | 3,629.73 | 1.7 | 12.92 | 4465.32 | 1.4 |

| Outer Mission | 451 | 5,666.26 | 2.7 | 12.56 | 4018.60 | 1.2 |

| Mission¶ | 848 | 13,482.28 | 6.4 | 15.90 | 5174.88 | 1.6 |

| Inner Richmond | 372 | 4,571.72 | 2.1 | 12.29 | 3540.19 | 1.1 |

| Hayes Valley | 223 | 3,714.30 | 1.7 | 16.66 | 5392.34 | 1.7 |

| Sunset/Parkside¶ | 1639 | 18,603.18 | 8.8 | 11.35 | 3370.70 | 1.0 |

| Lone Mountain/USF | 206 | 2,495.98 | 1.2 | 12.12 | 3497.41 | 1.1 |

| Twin Peaks | 138 | 1,815.66 | 0.8 | 13.16 | 3689.85 | 1.1 |

| Bernal Heights | 398 | 5,453.30 | 2.6 | 13.70 | 4567.62 | 1.4 |

| Inner Sunset | 389 | 4,824.47 | 2.3 | 12.40 | 3162.91 | 1.0 |

| Mission Bay | 76 | 1,242.73 | 0.6 | 16.35 | 3351.69 | 1.0 |

| Russian Hill | 378 | 4,184.48 | 2.0 | 11.07 | 3602.49 | 1.1 |

| Glen Park | 147 | 1,932.97 | 0.9 | 13.15 | 4079.52 | 1.3 |

| FiDi/South Beach | 175 | 2,645.95 | 1.2 | 15.12 | 3701.05 | 1.1 |

| Presidio Heights | 168 | 1,936.19 | 0.9 | 11.52 | 2900.20 | 0.9 |

| Pacific Heights | 289 | 3,555.10 | 1.7 | 12.30 | 2541.04 | 0.8 |

| Haight Ashbury | 163 | 2,535.71 | 1.2 | 15.56 | 4225.27 | 1.3 |

| Castro/Upper Market | 282 | 4,375.01 | 2.1 | 15.51 | 3874.31 | 1.2 |

| Marina | 314 | 3,564.39 | 1.7 | 11.35 | 3028.40 | 0.9 |

| Noe Valley | 292 | 3,926.27 | 1.8 | 13.45 | 3706.12 | 1.1 |

| West of Twin Peaks¶ | 785 | 9,022.00 | 4.3 | 11.49 | 3360.37 | 1.0 |

| Seacliff | 41 | 394.44 | 0.2 | 9.62 | 2109.32 | 0.6 |

| Potrero Hill | 159 | 2,566.86 | 1.2 | 16.14 | 4981.92 | 1.5 |

| Presidio | 16 | 334.41 | 0.1 | 20.90 | 3204.11 | Ref |

| All# | 15,687 | 211,661.99 | 100 | 13.49 | 4381.32 | 1.4 |

Ordered by increasing median household income.

YLL % = YLL/total YLL for city.

Average YLL = YLL/deaths.

Age-standardized YLL rate per 100,000 persons per year.

Presidio neighborhood (highest median household income) is reference group for ratio comparison.

Contributes >4% of YLL for city.

Includes n = 109 nongeocoded deaths and n = 18 deaths from nonincluded park neighborhoods Golden Gate, McLaren, Lincoln.

AYLL, age-adjusted years of life lost; FiDi, Financial District; SoMa, South of Market; USF, University of San Francisco; YLL, years of life lost

Table 3.

Adjusted Years of Life Lost for Top 5 Causes of Death, Homicide, and Chronic Disease by San Francisco Neighborhood

| Neighborhood∗ | COD#1 | AYLL COD#1 | COD#2 | AYLL COD#2 | COD#3 | AYLL COD#3 | COD#4 | AYLL COD#4 | COD#5 | AYLL COD#5 | Homicide rank |

AYLL homicide |

AYLL chronic disease† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinatown | CVA | 578.10 | CAD | 538.38 | Lung Ca | 501.83 | Liver Ca | 355.74 | HTN | 343.83 | 20 | 38.40 | 3967.84 |

| Tenderloin | Drug | 2026.10 | CAD | 1095.69 | HTN | 853.25 | EtOH | 772.67 | Lung Ca | 709.39 | 14 | 261.48‡ | 8644.10‡ |

| SoMa | Drug | 1485.40 | CAD | 949.78 | HIV | 757.72 | HTN | 653.27 | EtOH | 627.83 | 7 | 475.47‡ | 7230.37‡ |

| Treasure Island | Drug | 573.54 | Liver Ca | 549.74 | HIV | 413.56 | Unintent | 412.88 | Lymph | 308.52 | 10 | 62.81 | 2275.54 |

| Lakeshore | CAD | 747.01 | Drug | 534.48 | Lung Ca | 416.67 | Suicide | 398.23 | CRC | 388.10 | 16 | 103.14 | 4100.83‡ |

| Visitacion Valley | CAD | 873.84 | Lung Ca | 663.67 | CVA | 615.72 | Drug | 428.3 | Homicide | 354.36 | 5 | 354.36‡ | 4919.34‡ |

| Bayview/Hunters Point | CAD | 940.67 | Lung Ca | 678.63 | HTN | 627.52 | CVA | 616.84 | Homicide | 590.60 | 5 | 590.60‡ | 5892.64‡ |

| Western Addition | CAD | 697.11 | HTN | 592.18 | CVA | 504.79 | Lung Ca | 476.92 | Drug | 424.84 | 7 | 305.10‡ | 4610.38‡ |

| Japantown | Lung Ca | 718.64 | Liver Ca | 582.43 | Unintent | 566.68 | CAD | 564.27 | Drug | 515.80 | — | 0 | 4279.95‡ |

| Nob Hill | CAD | 741.94 | Lung Ca | 479.99 | HTN | 455.30 | Drug | 418.05 | CVA | 395.74 | 20 | 29.35 | 4562.82‡ |

| Excelsior | CAD | 746.45 | Lung Ca | 565.37 | CVA | 370.15 | HTN | 238.81 | EtOH | 197.26 | 19 | 45.79 | 3564.14 |

| Outer Richmond | CAD | 741.51 | CVA | 327.67 | Lung Ca | 327.41 | HTN | 241.58 | Pancreas | 190.39 | 19 | 33.84 | 3214.01 |

| Oceanview | CAD | 717.49 | Lung Ca | 379.61 | Homicide | 352.17 | CVA | 340.17 | HTN | 231.01 | 3 | 352.17‡ | 3484.85 |

| Portola | CAD | 627.82 | Lung Ca | 563.38 | CVA | 412.67 | CRC | 341.29 | Breast Ca | 320.96 | 13 | 145.78‡ | 4086.52 |

| North Beach | CAD | 655.32 | Lung Ca | 568.05 | EtOH | 450.12 | HTN | 410.29 | Drug | 312.67 | 19 | 61.64 | 4057.94 |

| Outer Mission | CAD | 656.51 | CVA | 422.39 | Lung Ca | 344.11 | CRC | 273.87 | HTN | 265.74 | 20 | 51.22 | 3539.51 |

| Mission | CAD | 685.75 | Drug | 574.46 | HTN | 458.71 | EtOH | 378.18 | CVA | 332.73 | 19 | 95.88 | 4612.49‡ |

| Inner Richmond | CAD | 671.63 | Lung Ca | 449.99 | CVA | 359.79 | HTN | 302.85 | CRC | 220.75 | 20 | 41.74 | 3131.12 |

| Hayes Valley | CAD | 731.47 | Lung Ca | 558.26 | HTN | 519.48 | Drug | 391.17 | CVA | 377.94 | 11 | 225.96‡ | 4890.48‡ |

| Sunset/Parkside | CAD | 612.63 | Lung Ca | 446.84 | CVA | 266.95 | HTN | 206.13 | CRC | 171.23 | 19 | 26.61 | 3016.30 |

| Lone Mountain/USF | CAD | 414.82 | CVA | 411.07 | Lung Ca | 305.79 | HTN | 304.04 | CRC | 299.56 | 19 | 30.91 | 3227.00 |

| Twin Peaks | CVA | 379.05 | CAD | 330.90 | HTN | 323.83 | Lung Ca | 309.97 | Suicide | 276.51 | 18 | 56.58 | 3180.74 |

| Bernal Heights | CAD | 678.12 | Lung Ca | 452.79 | HTN | 432.19 | CVA | 353.35 | Alzheimer | 284.82 | 16 | 130.15‡ | 4024.73 |

| Inner Sunset | CAD | 484.34 | Lung Ca | 421.73 | HTN | 232.67 | CVA | 230.90 | Lymph | 195.68 | 20 | 32.90 | 2851.52 |

| Mission Bay | Liver Ca | 419.45 | PNA/flu | 382.75 | Lung Ca | 381.81 | HIV | 322.35 | HTN | 250.42 | 16 | 68.10 | 2803.40 |

| Russian Hill | CAD | 558.35 | Lung Ca | 409.95 | CVA | 313.92 | Suicide | 260.72 | HTN | 258.83 | 19 | 61.41 | 3122.19 |

| Glen Park | CAD | 885.73 | Lung Ca | 478.89 | CVA | 320.70 | Pancreas | 292.23 | PNA/flu | 239.05 | 19 | 61.48 | 3575.03 |

| FiDi/South Beach | CAD | 660.07 | HTN | 396.77 | Lung Ca | 386.40 | CVA | 347.00 | COPD | 269.20 | 19 | 47.31 | 3263.32 |

| Presidio Heights | CAD | 444.89 | Lung Ca | 359.43 | CVA | 300.71 | Breast Ca | 218.00 | Alzheimer | 212.43 | — | 0 | 2639.13 |

| Pacific Heights | CAD | 331.22 | Lung Ca | 300.05 | Suicide | 238.75 | Pancreas | 202.94 | EtOH | 193.88 | 20 | 9.33 | 2160.24 |

| Haight Ashbury | Lung Ca | 639.18 | CAD | 532.00 | Pancreas | 369.97 | CVA | 339.73 | CRC | 294.97 | 19 | 31.18 | 3926.07 |

| Castro/Upper Market | CAD | 617.25 | Lung Ca | 452.79 | HTN | 390.20 | Suicide | 336.45 | HIV | 309.69 | 15 | 79.28 | 3280.47 |

| Marina | CAD | 491.11 | Lung Ca | 349.25 | CVA | 290.46 | HTN | 260.07 | Alzheimer | 213.41 | 19 | 10.66 | 2828.32 |

| Noe Valley | CAD | 628.57 | Lung Ca | 394.43 | HTN | 349.11 | Suicide | 319.41 | Alzheimer | 245.18 | 16 | 92.19 | 3165.82 |

| West of Twin Peaks | CAD | 511.26 | Lung Ca | 394.22 | CVA | 287.44 | Alzheimer | 224.61 | Suicide | 214.61 | 20 | 12.7 | 2938.47 |

| Seacliff | Lung Ca | 650.99 | CAD | 346.68 | Dementia | 282.56 | HTN | 248.84 | Liver Ca | 166.77 | — | 0 | 2109.32 |

| Potrero Hill | CAD | 709.78 | Lung Ca | 574.34 | Homicide | 518.82 | HTN | 338.19 | Lymph | 326.83 | 3 | 518.82‡ | 4087.15 |

| Presidio | HTN | 604.50 | Drug | 604.50 | Suicide | 479.59 | HIV | 421.92 | Breast Ca | 339.16 | — | 0 | 2623.36 |

| All§ | CAD | 649.65 | Lung Ca | 448.45 | CVA | 342.64 | Drug | 331.49 | HTN | 331.15 | 18 | 125.86 | 3828.79 |

Ordered by increasing median household income.

Chronic disease = CAD, Lung Ca, CVA, HTN, COPD, CRC, Liver Ca, Alzheimer, Pancreas, DM, Breast Ca, Dementia, HIV, Lymphoma, Drug, EtOH (excluded: PNA/flu, Suicide, Homicide, Unintent)

Top 10 highest burdens of AYLL for homicide and chronic disease, respectively

Including n = 109 non-geocoded deaths and n = 18 deaths from non-included park neighborhoods Golden Gate, McLaren, Lincoln

AYLL, adjusted years of life lost; Breast Ca, breast cancer; CAD, ischemic heart disease; COD, cause of death; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder; CRC, cancer colon/rectum; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; Drug, Drug use disorder; EtOH, alcohol-attributable diseases and disorders; FiDi, Financial District; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HTN, hypertensive diseases; Liver Ca, liver cancer; Lung Ca, lung/trachea/bronchial cancer; Lymph, lymphoma/multiple myeloma; Pancreas, pancreas cancer; PNA/flu, influenza and pneumonia; SoMa, South of Market, Unintent, unintentional, non-transport accidents; USF, University of San Francisco

Neighborhood demographics

San Francisco neighborhoods varied in their demographic make-up (Table 1). Thirteen neighborhoods (34.2%) had higher percent population Black than the citywide level, and 12 (31.6%) had more than 50% minority race (any race other than White, including 2 races). Eighteen (47.4%) fell under the citywide MHI, 15 (39.5%) were above the citywide PBPL, and 6 (15.8%) met the federal definition of “poverty area” with PBPL’s greater than 20%.18,19 Eleven (28.9%) had more individuals without a high school diploma than the citywide level, and 4 (10.5%) met the definition of an “undereducated area” where at least 25% of persons aged 25 years old or older have not completed high school.19 For the civilian labor force 16 years and older, 6.65% of the population were unemployed, with 15 neighborhoods (39.5%) above the citywide level of unemployment. Four neighborhoods had higher percent Black, without high school diploma, unemployment, PBPL, and lower MHI measurements when compared with citywide levels: Tenderloin, Visitacion Valley, Bayview/Hunters Point, and Oceanview.

Neighborhood deaths

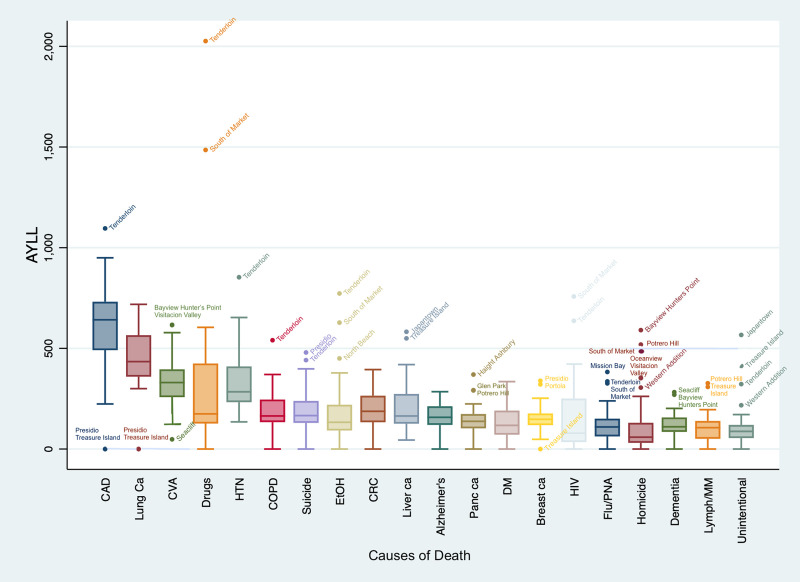

The top causes and distribution of deaths varied at the neighborhood level (Tables 2 and 3 and Figs. 2 and 3). Sunset/Parkside was the largest contributor based on total deaths (N = 1,639) and YLLs (18,603.18), whereas Treasure Island had the highest overall average YLL per death across all causes (24.37) and the Tenderloin had the most total AYLLs (9,995.56). The highest number of deaths were attributable to ischemic heart disease (N = 355) in the Sunset. By neighborhood, ischemic heart disease was also the most frequent top cause of death (N = 33, 86.8% of neighborhoods), YLL (N = 30, 78.9%), and AYLL (N = 27, 71.0%; Figs. 2 and 3 and Table 3). Drug use disorders in the Tenderloin were responsible for the highest overall YLL and AYLL (3,730.94 and 2,026.10, respectively). Average YLL per death for all causes ranged from 9.62 (Seacliff) to 24.37 (Treasure Island). Average YLL per death by cause ranged from 6.79 (multiple neighborhoods and causes) to 31.09 (Presidio, unintentional injury). The most common cause of highest average YLL across all neighborhoods was homicide (N = 24 neighborhoods, 63.1%).

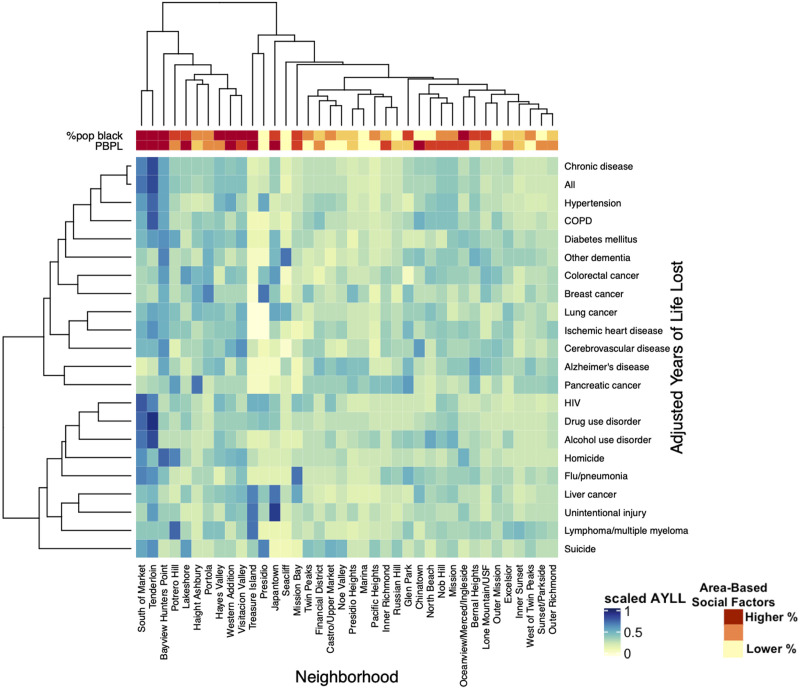

Figure 2.

Adjusted years of life lost for the top 20 causes of death in San Francisco by neighborhood. AYLL, adjusted years of life lost; Breast Ca, breast cancer; CAD, ischemic heart disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder; CRC, cancer colon/rectum; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; DM, diabetes mellitus; Drugs, drug use disorder; EtOH, alcohol-attributable diseases and disorders; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HTN, hypertensive diseases; Liver Ca, liver cancer; Lung Ca, lung/trachea/bronchial cancer; Lymph/MM, lymphoma/multiple myeloma; Panc Ca, pancreas cancer; flu/PNA, influenza and pneumonia; Unintent, unintentional, nontransport accidents.

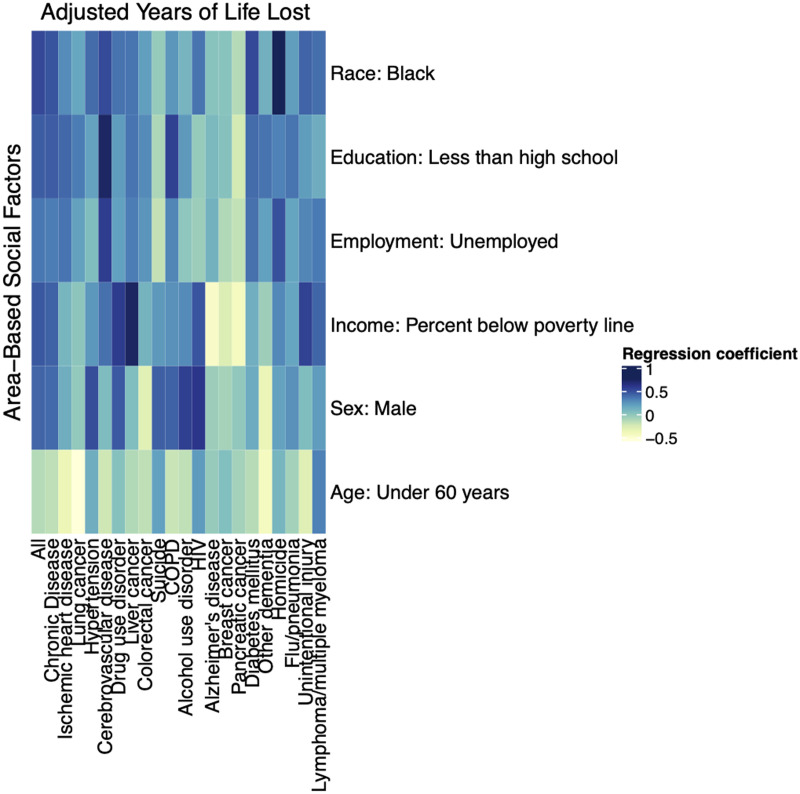

Figure 3.

Association between adjusted years of life lost (AYLL) for the top 20 causes of death and select area-based social factors across San Francisco neighborhoods. The causes of death on the x axis are ranked by the sum of AYLL across San Francisco neighborhoods from highest to lowest. COPD, chronic obstructive; pulmonary disorder; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Homicide was in the actual top 20 causes of death based on YLL for 47.1% (N = 16) neighborhoods that registered a homicide death, with average YLL per death ranging from 18.37 (Russian Hill) to 29.20 (Treasure Island). Neighborhoods with the highest AYLL for homicide included Bayview/Hunters Point, Potrero Hill, SoMa, Visitacion Valley, Oceanview, and Western Addition, all high outliers when compared with the median across neighborhoods (Fig. 2 and Table 3). Neighborhoods with the highest AYLL for chronic diseases included the Tenderloin, SoMa, Bayview/Hunters Point, Visitacion Valley, and Hayes Valley, with the first three neighborhoods being high outliers (Table 3).

Eight neighborhoods (21.0%) accounted for 47.9% of citywide YLLs, with top contributors being Sunset, Tenderloin, and Mission (Table 2). However, these calculations do not take into account population age-adjustment. There was significant overlap amongst neighborhoods that fell within the top 10 for total AYLL and top 10 AYLL owing to homicide (70%) and chronic diseases (90%; Fig. 4A). Six neighborhoods were within the top 10 across all 3 categories: Tenderloin, SoMa, Bayview/Hunters Point, Visitacion Valley, Western Addition, and Hayes Valley. Two neighborhoods (SoMa and Tenderloin) were high outliers for the total burden of AYLLs (Table 2). When focusing on specific causes of death, certain neighborhoods repeatedly appeared as high outliers with more AYLLs when compared with the median across neighborhoods, including the Tenderloin (N = 9 outliers), SoMa (N = 5), Potrero Hill (N = 3), Bayview (N = 3), and Treasure Island (N = 3; Fig. 2).

Figure 4.

(A) San Francisco neighborhoods with most adjusted years of life lost (AYLL) for homicide, chronic disease, and all-causes for top 20 causes of death juxtaposed with historical redlining. (B) City and County of San Francisco Home Owner’s Loan Corporation (HOLC) Residential Security Map (1937).17 Image provided courtesy of the San Francisco Department of Public Health

The effects of these disease processes can be seen across generations, as indicated by average YLL per death ranges spanning 13.09 years (Seacliff) to 21.11 years (Lakeshore). Lowest average YLLs were from dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, HIV, and influenza/pneumonia, whereas highest averages were overwhelmingly from homicide, making it a leading cause of premature death in San Francisco.

Relationship between deaths and social factors

Certain area-based social factors were shown to be associated with higher neighborhood AYLL burdens (Figs. 3–5 and Supplemental Digital Content 1, available at http://links.lww.com/XCS/A0). When examining all causes of death, a neighborhood’s AYLL burden tended to rise with increasing percent population male (630.30 AYLLs per 1 standard deviation change in percent population male, p = 0.02), Black (791.22; p = 0.00), unemployed (542.63; p = 0.08), less than high school education (671.25; p = 0.04), and PBPL (697.93; p = 0.01). This held true for AYLL attributable to homicide and chronic disease across the same social factors. A neighborhood’s percent population Black was associated with the largest increase in AYLL for all deaths (791.22; p = 0.00) and those specifically attributable to chronic disease (613.56; p = 0.01) and homicide (113.72; p = 0.00). Figure 5 graphically shows that neighborhoods with higher percent population Black and PBPL were frequently burdened with more AYLLs, such as SoMa, Tenderloin, Bayview/Hunters Point, Western Addition, and Visitacion Valley.

Figure 5.

Adjusted years of life lost (AYLL) for the top 20 causes of death, percent population Black (%pop black), and percent population below the poverty level (PBPL) across San Francisco neighborhoods. The hierarchies are generated by the hierarchical clustering algorithm, which clusters similar groups based on a distance matrix. The x axis hierarchical clustering groups similar neighborhoods and the y-axis groups similar AYLLs. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; USF, University of San Francisco.

Of the 38 present-day neighborhoods examined in this study, N = 22 (57.9%) contained areas that were previously redlined (Fig. 4). Of these 22 neighborhoods, 6 neighborhoods were within the top 10 for highest YLLs (2 neighborhoods within the top 10 were ungraded: Tenderloin and SoMa), 5 were within the top 10 for highest average YLL per death (4 were ungraded: Tenderloin, SoMa, Mission Bay, and Treasure Island), 8 were within the top 10 for overall AYLL burden, 8 had the most AYLL attributable to homicide, and 7 had the most AYLL attributable to chronic diseases. Across the above categories, 2 of the most affected neighborhoods that were not redlined (SoMa and Tenderloin) were sparsely settled and not included in the 1937 grading (Fig. 4B).

DISCUSSION

Our study highlights the disproportionate burden of deaths shouldered by socially disadvantaged San Franciscans, many of whom live in neighborhoods that align with areas subjected to past discriminatory policies and persistent structural inequities including disinvestment. These neighborhoods had lower MHI and higher PBPL than citywide levels, were largely majority Black or other minority racial/ethnic group and had higher percentages of unemployment and low education. The key drivers of premature deaths in these neighborhoods were chronic diseases and violence, affecting both the young and old, making it difficult for one generation to take care of another and for entire communities to emerge from a cycle of poverty and poor health. Because individual race/ethnicity is accepted as a social construct,20 racial health disparities are the downstream effect of discriminatory and racist policies, such as those tied to place of residence, which caused segregation, displacement, and fragmentation.21,22 These disparate health outcomes are persisting with the COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately impacting many of the same disadvantaged communities highlighted in our study.23

Whereas many studies focus on individual-level social factors when discussing health disparities, there is increased recognition of the significant variation in health outcomes at the neighborhood level24-26 and the independent effect place of residence has on its citizens, related to the “structural” determinants of health.27-29 Using data from the Alameda County Study, researchers found an increased 9-year risk of mortality for residents of a federally designated poverty area in Oakland, California, as compared with residents throughout the rest of Oakland, even when controlling for age, sex, race, and numerous other social factors at the individual level.30 Using an index of inequality built on area-based social factors in England, a 15-year study found 1 in 3 premature deaths were attributable to socioeconomic inequality, with obesity, viral hepatitis, drug use, HIV, and tuberculosis as the most unequal contributors.7

Physical disability and deaths associated with chronic disease can be intergenerational,31,32 and when added to existing barriers from structural racism21 this can render entire households economically disadvantaged33 and reinforces a cycle of worse health outcomes and reduced quality of life.34 Communities plagued by firearm violence have been shown to experience a higher prevalence of preterm birth, asthma, infections, and substance use,35 affecting both the mother and the child. Many battle with concomitant adverse childhood experiences, mental health issues like depression and anxiety, and chronic or toxic stress that are common in poor and unsafe neighborhoods,36-38 not to mention the actual increased risk of severe and/or violent injury or reinjury in socially disadvantaged communities.39,40 Although unable to control for individual-level characteristics, our data suggest similar neighborhood social effects on health across generations.

It is clear from our study that specific San Francisco neighborhoods were dually burdened with poor health, as indicated by high AYLL burden, and social disadvantage, including the Tenderloin, SoMa, Bayview/Hunter’s Point, Visitacion Valley, Western Addition, and Hayes Valley, some of which have been highlighted in previous studies,41,42 with social disadvantage reinforcing if not driving poor health. Our data show that neighborhoods with scarce educational opportunities, high unemployment, and high levels of poverty had more violent deaths and worse health outcomes, based on AYLL burden, highlighting that without wealth, we cannot have our health. Disinvestment in a community’s development and infrastructure, such as lack of roads, green space, financial institutions, grocery stores, and healthcare facilities, has been shown to lead to worse health outcomes,43,44 whereas the development of vacant lots leads to less violence and crime and increased perceptions of safety.45 Many of the San Francisco neighborhoods highlighted in our study are repeatedly mentioned when discussing food deserts, unhealthy food environments, shortages of health professionals, and low levels of tree canopies, among other community development factors.23,46 Many of the same neighborhoods rank poorly on SFDPH’s San Francisco Climate and Health Program Community Resiliency Index, a summary of 36 indicators spanning hazards, environment, transportation, community, public realm, housing, economic, health, and demographic categories, with Chinatown, Bayview/Hunter’s Point, Downtown/Civic Center (Tenderloin/Hayes Valley), Visitacion Valley, and Treasure Island considered the most vulnerable.47

There were select San Francisco neighborhoods that did not follow the patterns outlined above. Despite low social factor rankings, Chinatown did not rank highly in premature deaths. This could be attributable to strong social cohesion and trust within the community from a shared background, which has been associated with improved health outcomes and is suggested by the 80.9% Asian population.8 Also of note, the Chinatown area was ungraded on the 1937 HOLC map (Fig. 4B). Although the West of Twin Peaks and Sunset neighborhoods had more advantageous social factors, they shouldered higher YLLs, which could potentially be explained by long-term care facilities in these neighborhoods whose residents were not excluded from the analysis. Future studies will require gathering both individual and area-based social factors to better assess causation. These quantitative data would be enhanced by qualitative, community-based participatory research to further explore the disparities highlighted by our study and to identify and enact effective solutions.

A lot can be acted upon with the current study results. At the hospital level, we can measure a patient’s individual SDoH to identify deficits that may be affecting their health. Social care is an essential component of healthcare, as highlighted in a recent study presenting strategies to improve SDoH to attenuate violence.48 Additional approaches include implementing trauma-informed care, investing in at-risk communities, and advocacy. Through the Affordable Care Act a hospital is required to look at its community’s needs and identify areas for investment. For example, does the hospital buy its bulk foods from local vendors? Do they have a vocational training program for at-risk communities?48 At the city, county, and state level, leaders across sectors must collaborate to remove historical discriminatory policies that continue to disproportionately harm certain communities.

Investigators in other cities who want to use this methodology can start by building relationships with their Departments of Public Health who typically have data on YLL and AYLL. In addition, using the latest census data can serve to overlay important death data with SDoH at the neighborhood level. The combination of these data can set a framework in motion to identify priorities after understanding the impact of chronic diseases and violence on vulnerable populations.

There are several limitations to our study that warrant discussion. Our data lack granularity at the individual-level to control for individual effects, potentially predisposing our conclusions to sociologistic fallacy, where we ascribe certain characteristics to the neighborhood instead of the individual.49 Neighborhoods also must be considered within the broader context of the cities, counties, and states within which they reside and the policies shaping where people live, as well as changes in place of residence over time. The small effect neighborhoods may have in comparison with individual-level effects for members of discriminated groups must also be considered.29 Our small sample size of 38 neighborhoods could have limited our ability to find statistically significant differences where significant health effects actually existed. However, given our interest in neighborhoods as a relevant social and political construct, as well as the cohesion between our findings and existing literature, we believe the correct level of data was used and we were careful to make statements of association without definite causation.

The data only capture the primary cause of death without comorbidities, suggesting that there is likely a higher burden of disease in these neighborhoods and citywide than we are able to account for. One hundred twenty-seven deaths were removed from the neighborhood-level analysis because of either lack of geocoding or being parks. Although 97 of these deaths were chronic disease-related and 9 were homicides, the majority were drug-related (N = 36) and in total only accounted for 0.81% of overall deaths citywide, which would minimally effect our results. In our decision to select only homicide deaths to represent violence, we could be underestimating the effect of violence in a community. However, we believe this was the most valid approach for our hypothesis given suicide does not represent interpersonal violence, we were unable to further qualify deaths in the category of “injuries of undetermined intent and their sequelae,” and there was a low number (N = 1) of deaths attributable to legal intervention. We were also limited in gender categories based on census classifications at the time, which will be important to discern and highlight in future analyses owing to worse health disparities for transgender and nonbinary populations.50

CONCLUSIONS

Our study highlights the mortality inequity burdening people living in disadvantaged San Francisco neighborhoods. This aligns with areas subjected to historical discriminatory policies like redlining, suggesting social disadvantage and racism are drivers of poor health. These data emphasize the need to address past injustices and move toward equal access to wealth and health for all San Franciscans. This will require cross-sectoral collaboration, commitment, and action to eradicate these deep-seated inequities and to create equal opportunities for all to not only survive but thrive.

Author Contributions

Study conception and design: Boeck, Wei, Robles, Nwabuo, Juillard, Bibbins-Domingo, Hubbard, Dicker

Acquisition of data: Robles, Nwabuo, Dicker

Analysis and interpretation of data: Boeck, Wei, Robles, Nwabuo, Hubbard, Dicker, Plevin

Drafting of manuscript: Boeck, Wei, Hubbard, Dicker

Critical revision: Boeck, Wei, Robles, Nwabuo, Plevin, Juillard, Bibbins-Domingo, Hubbard, Dicker

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ACS

- American Community Survey

- AYLL

- adjusted years of life lost

- CDPH

- California Department of Public Health

- HIV

- human immunodeficiency virus

- MHI

- median household income

- PBPL

- Percent Below Poverty Level

- SDoH

- social determinants of health

- SFDPH

- San Francisco Department of Public Health

- SoMa

- South of Market

- YLL

- years of life lost

Disclosure Information: Nothing to disclose.

Presented virtually at the American College of Surgeons 107th Annual Clinical Congress, Scientific Forum, Washington, DC, October 2021.

Present address: Department of Surgery (Robles) and Department of Psychiatry (Nwabuo), University of California, Davis, Sacramento, CA.

Supplemental digital content for this article is available at http://links.lww.com/XCS/A0.

REFERENCES

- 1.CSDH. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chetty R, Stepner M, Abraham S, et al. The association between income and life expectancy in the United States, 2001-2014. JAMA. 2016;315:1750–1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braveman P, Arkin E, Orleans T, et al. What is health equity? and what difference does a definition make?. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braveman P. What are health disparities and health equity? We need to be clear. Public Health Rep. 2014;129 Suppl 2:5–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kind AJH, Buckingham WR. Making neighborhood-disadvantage metrics accessible — The neighborhood atlas. New Engl J Med. 2018;378:2456–2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim D, Glazier RH, Zagorski B, et al. Neighbourhood socioeconomic position and risks of major chronic diseases and all-cause mortality: A quasi-experimental study. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e018793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewer D, Jayatunga W, Aldridge RW, et al. Premature mortality attributable to socioeconomic inequality in England between 2003 and 2018: An observational study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e33–e41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pickett KE, Wilkinson RG. Income inequality and health: a causal review. Soc Sci Med. 2015;128:316–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kendi IX. How to be an Antiracist. New York: One World, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rothstein R. The color of law: a forgotten history of How our Government Segregated America. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chetty R, Hendren N, Kline P, Saez E. Where is the land of opportunity? The geography of intergenerational mobility in the United States. Q J Econ. 2014;129:1553–623. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krieger N. Epidemiology and the web of causation: Has anyone seen the spider? Soc Sci Med. 1994;39:887–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yen IH, Syme SL. The social environment and health: A discussion of the epidemiologic literature. Annu Rev Public Health. 1999;20:287–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mortality. 2019 San Francisco Community Health Needs Assessment. San Francisco, CA. Available at: http://www.sfhip.org/mortality.html. Accessed April 24, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aragón TJ, Lichtensztajn DY, Katcher BS, et al. Calculating expected years of life lost for assessing local ethnic disparities in causes of premature death. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. About Chronic Diseases. Atlanta, Georgia. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/about/index.htm. Accessed May 27, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelson RK, Winling L, Marciano R, Connolly N. Mapping Inequality. American Panorama. Available at: https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/#loc=12/37.783/-122.473&city=san-francisco-ca&text=downloads. Accessed August 20, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, et al. Race/ethnicity, gender, and monitoring socioeconomic gradients in health: a comparison of area-based socioeconomic measures–The public health disparities geocoding project. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1655–1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krieger N. Overcoming the absence of socioeconomic data in medical records: Validation and application of a census-based methodology. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:703–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krieger N. Methods for the scientific study of discrimination and health: An ecosocial approach. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:936–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, et al. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389:1453–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fullilove MT, Wallace R. Serial forced displacement in American cities, 1916–2010. Journal of Urban Health. 2011;88:381–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Population Health and Health Equity. UCSF Health Atlas. San Francisco. Available at: https://healthatlas.ucsf.edu/. Accessed May 7, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dwyer-Lindgren L, Stubbs RW, Bertozzi-Villa A, et al. Variation in life expectancy and mortality by cause among neighbourhoods in King County, WA, USA, 1990-2014: A census tract-level analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2:e400–e410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen JT, Rehkopf DH, Waterman PD, et al. Mapping and measuring social disparities in premature mortality: The impact of census tract poverty within and across Boston neighborhoods, 1999-2001. J Urban Health. 2006;83:1063–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Durfey SNM, Kind AJH, Buckingham WR, et al. Neighborhood disadvantage and chronic disease management. Health Serv Res. 2019;54 Suppl 1:206–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ludwig J, Sanbonmatsu L, Gennetian L, et al. Neighborhoods, obesity, and diabetes–A randomized social experiment. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1509–1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomez SL, Shariff-Marco S, DeRouen M, et al. The impact of neighborhood social and built environment factors across the cancer continuum: Current research, methodological considerations, and future directions. Cancer. 2015;121:2314–2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diez Roux AV. Investigating neighborhood and area effects on health. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1783–1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haan M, Kaplan GA, Camacho T. Poverty and health. Prospective evidence from the Alameda County study. Am J Epidemiol. 1987;125:989–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chiu YH, Coull BA, Sternthal MJ, et al. Effects of prenatal community violence and ambient air pollution on childhood wheeze in an urban population. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:713–722.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murray CJ, Kulkarni SC, Michaud C, et al. Eight Americas: investigating mortality disparities across races, counties, and race-counties in the United States. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jaspers L, Colpani V, Chaker L, et al. The global impact of non-communicable diseases on households and impoverishment: A systematic review. Eur J Epidemiol. 2015;30:163–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Didsbury MS, Kim S, Medway MM, et al. Socio-economic status and quality of life in children with chronic disease: A systematic review. J Paediatr Child Health. 2016;52:1062–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goin DE, Rudolph KE, Gomez AM, et al. Mediation of firearm violence and preterm birth by pregnancy complications and health behaviors: Addressing structural and postexposure confounding. Am J Epidemiol. 2020;189:820–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weil AR. Violence and health. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38:1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woods-Jaeger B, Berkley-Patton J, Piper KN, et al. Mitigating negative consequences of community violence exposure: Perspectives from African American youth. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38:1679–1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rivara F, Adhia A, Lyons V, et al. The effects of violence on health. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38:1622–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chong VE, Lee WS, Victorino GP. Neighborhood socioeconomic status is associated with violent reinjury. J Surg Res. 2015;199:177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lawson F, Schuurman N, Amram O, et al. A geospatial analysis of the relationship between neighbourhood socioeconomic status and adult severe injury in Greater Vancouver. Inj Prev. 2015;21:260–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang JS. Health in the Tenderloin: a resident-guided study of substance use, treatment, and housing. Soc Sci Med. 2017;176:166–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guan A, Lichtensztajn D, Oh D, et al. ; San Francisco Cancer Initiative Breast Cancer Task Force. Breast cancer in San Francisco: Disentangling disparities at the neighborhood level. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2019;28:1968–1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nguyen QC, Khanna S, Dwivedi P, et al. Using Google Street View to examine associations between built environment characteristics and U.S. health outcomes. Prev Med Rep. 2019;14:100859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kivimäki M, Batty GD, Pentti J, et al. Modifications to residential neighbourhood characteristics and risk of 79 common health conditions: A prospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6:e396–e407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Branas CC, South E, Kondo MC, et al. Citywide cluster randomized trial to restore blighted vacant land and its effects on violence, crime, and fear. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:2946–2951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Community Health Data. San Francisco. Available at: http://www.sfhip.org/chna/community-health-data/. Accessed June 4, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Neighborhood Summary. San Francisco Climate & Health Program. San Francisco. Available at: https://sfclimatehealth.org/neighborhoods/. Accessed June 4, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dicker RA, Thomas A, Bulger EM, et al. ; ISAVE Workgroup; Members of the ISAVE Workgroup. Strategies for trauma centers to address the root causes of violence: Recommendations from the improving social determinants to attenuate violence (ISAVE) Workgroup of the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. J Am Coll Surg. 2021;233:471–478.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Diez-Roux AV. Bringing context back into epidemiology: Variables and fallacies in multilevel analysis. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:216–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Teti M, Kerr S, Bauerband LA, et al. A qualitative scoping review of transgender and gender non-conforming people’s physical healthcare experiences and needs. Front Public Health. 2021;9:598455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.