Abstract

Cardiovascular disease is a prevalent and prognostically important comorbidity among patients with kidney disease, and individuals with kidney disease make up a sizeable proportion (30%–60%) of patients with cardiovascular disease. However, several systematic reviews of cardiovascular trials have observed that patients with kidney disease, particularly those with advanced kidney disease, are often excluded from trial participation. Thus, currently available trial data for cardiovascular interventions in patients with kidney disease may be insufficient to make recommendations on the optimal approach for many therapies. The Kidney Health Initiative, a public-private partnership between the American Society of Nephrology and the US Food and Drug Administration, convened a multidisciplinary, international work group and hosted a stakeholder workshop intended to understand and develop strategies for overcoming the challenges with involving patients with kidney disease in cardiovascular clinical trials, with a particular focus on those with advanced disease. These efforts considered perspectives from stakeholders, including academia, industry, contract research organizations, regulatory agencies, patients, and care partners. This article outlines the key challenges and potential solutions discussed during the workshop centered on the following areas for improvement: building the business case, re-examining study design and implementation, and changing the clinical trial culture in nephrology. Regulatory and financial incentives could serve to mitigate financial concerns with involving patients with kidney disease in cardiovascular trials. Concerns that their inclusion could affect efficacy or safety results could be addressed through thoughtful approaches to study design and risk mitigation strategies. Finally, there is a need for closer collaboration between nephrologists and cardiologists and systemic change within the nephrology community such that participation of patients with kidney disease in clinical trials is prioritized. Ultimately, greater participation of patients with kidney disease in cardiovascular trials will help build the evidence base to guide optimal management of cardiovascular disease for this population.

Keywords: cardiovascular, kidney disease, cardiorenal, cardiovascular trials

Introduction

Kidney disease is highly prevalent (30%–60%) among patients with cardiovascular disease and is a risk factor for worse cardiovascular outcomes (1,2). Thus, management of cardiovascular disease in patients with kidney disease is a common and important clinical problem, yet the evidence base to guide optimal treatment recommendations is limited. Previous reports have observed that the quantity and quality of nephrology trials have been low (2 –6), and patients with kidney disease have been under-represented in cardiovascular trials (1,2,7,8). However, extrapolation of results from cardiovascular trials conducted in the general population to patients with kidney disease may not be appropriate.

The exclusion of patients with kidney disease from cardiovascular trials has been well documented. Two systematic reviews published in 2006 (1,2) observed that 56%–80% of randomized controlled trials of cardiovascular interventions excluded patients with kidney disease. Although the authors issued strong recommendations for greater inclusion of these patients, their under-representation persists. More recently published reviews found that 46%–57% of cardiovascular trials likewise excluded patients with kidney disease, many of whom had advanced kidney disease (stage 4 CKD) and kidney failure (7,8).

These reviews highlight the need for more data to assess the risks and benefits of cardiovascular interventions among patients with kidney disease, a sizable and prognostically important subgroup that bears a high burden of cardiovascular disease (9). To better understand and develop strategies for overcoming the challenges with involving patients with kidney disease in cardiovascular trials, with an emphasis on those with advanced disease, the Kidney Health Initiative (KHI), a public-private partnership between the American Society of Nephrology and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (10), assembled a multidisciplinary, international work group with representation from a variety of stakeholders, including academia, industry, contract research organizations, regulatory agencies, and patients. The work group developed and implemented an informal polling mechanism designed to elicit the viewpoints of experts engaged in cardiovascular trials, patients, and care partners (Supplemental Appendices 1 and 2, Supplemental Tables 1 and 2). On the basis of this feedback, the group identified key methodologic, operational, and regulatory considerations for the design and conduct of cardiovascular trials involving patients with kidney disease.

To discuss these challenges and to develop actionable strategies to overcome them, a KHI-sponsored workshop was held in September 2018, convening a diverse group of stakeholders, including academic and industry trial sponsors, academic and contract research organizations, regulatory agencies, and patients, whose input was considered critical to the workshop’s deliberations.

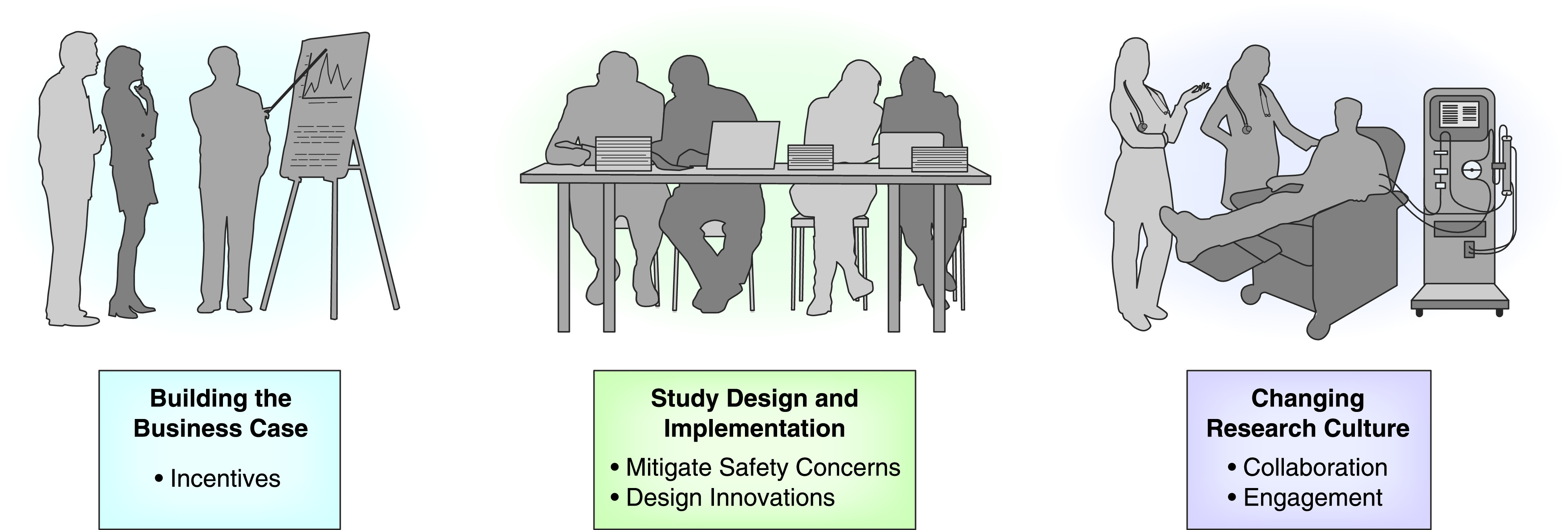

The workshop underscored the urgent need for action to successfully achieve the goal of greater participation of patients with kidney disease in cardiovascular trials. Since the time of the workshop, major nephrology trials (CREDENCE, DAPA-CKD, and FIDELIO-DKD) have been published that evaluated cardiovascular outcomes in patients with kidney disease (11 –13). However, these trials did not enroll those with eGFR<25 ml/min per 1.73 m2, indicating that an evidence gap remains (14,15) and the concepts discussed during the workshop remain relevant. This article highlights the challenges and solutions discussed during the workshop, focused around three key areas for improvement: building the business case, re-examining study design and implementation, and changing the clinical trial culture in nephrology (Figure 1, Table 1).

Figure 1.

Strategies to overcome the challenges related to involving patients with kidney disease in cardiovascular trials. A multipronged approach involving building the business case, improving study design and implementation, and changing the clinical trial culture in nephrology can foster greater participation of patients with kidney disease in cardiovascular trials.

Table 1.

Challenges with involving patients with kidney disease in cardiovascular trials and proposed solutions

| Challenges | Solutions |

| Building the business case | |

| Trial sponsor concerns | |

| Finite resources and competing priorities | Consider existing FDA programs (e.g., Orphan Designation, Breakthrough Therapy and Fast Track Designation, Accelerated Approval, and Priority Review Designation) |

| Inclusion of patients with advanced kidney disease could potentially skew efficacy and safety results and affect regulatory approval and product labeling | Financial incentives, such as market exclusivity extensions |

| Engage CMS and other payers early in the development process | |

| Incorporate feedback from patients throughout the development process | |

| Study design and implementation | |

| Safety concerns | |

| Higher risk of adverse events, drug interactions, nonadherence to the intervention, withdrawal from the trial | Develop strategies to mitigate safety concerns (e.g., novel study design, prohibit or restrict medications that interact with investigational product, understand effect of investigational product on eGFR, manage risks of exacerbating complications of kidney disease, such as hyperkalemia) |

| Financial and logistical burden of safety monitoring and reporting | |

| Potential reduction in data quality due to poor adherence and dropout from the study due to adverse events | |

| Concern that investigational product may affect kidney function or exacerbate complications of kidney disease | |

| Efficacy concerns and lack of innovative protocol designs | |

| Lack of efficacy or smaller effect size in subgroup with kidney disease, which could skew overall result toward the null | Consider whether there is adequate justification to exclude patients with advanced kidney disease |

| End points used in the general population may not be as relevant for patients with advanced kidney disease | Sponsor could be offered the option of enrolling patients with an eGFR below a certain threshold in a broader study but exclude them from key efficacy analyses |

| Use of protocol templates that excluded patients with kidney disease | Conduct dedicated cardiovascular trial for patients with advanced kidney disease in parallel with a cardiovascular trial in general population that excludes patients below a certain eGFR cutoff |

| Protocols designed without nephrologist input | Select appropriate end points and develop standardized cardiovascular outcome definitions for patients with advanced kidney disease and kidney failure |

| Include nephrologists in the development of cardiovascular trial protocols | |

| Recruitment concerns | |

| Prevalence of patients with advanced kidney disease is relatively low and may be a barrier to trial recruitment and enrollment | Seek guidance from patients with kidney disease on study materials (e.g., protocols) and how to optimize recruitment strategies |

| Create registries for patients with kidney disease in order to have “virtual” pool of potential participants | |

| Leverage best practices from trials that have successfully enrolled patients with advanced kidney disease and kidney failure | |

| Clinical trial culture in nephrology | |

| Lack of “on-study” culture and trial infrastructure in nephrology | |

| Lack of awareness and incentives for nephrologists to participate in trials | Offer financial and other incentives to physicians for participation in trials |

| Limited number of established sites and investigators with experience enrolling patients with advanced kidney disease | Enhance government (e.g., NHLBI, NIDDK), subspecialty society, and industry-sponsored funding |

| Challenges with communicating the value of trial participation to health systems | Provide training in trial planning and execution to trainees and junior investigators |

| Develop resources (e.g., papers, presentations) to support nephrologists’ participation in trials | |

| Encourage cross-specialty collaboration between cardiologists and nephrologists, leveraging existing organizations (e.g., ERA-EDTA, HFSA, KCVD, CRSA, INI-CRCT) and attendance at multidisciplinary meetings (e.g., CVCT, KDCT) | |

| Enrollment challenges | |

| High number of expected reportable adverse events may serve as a disincentive to site coordinators to enroll patients with advanced kidney disease | Compensation to sites to incentivize enrollment of patients with advanced kidney disease |

| Financial and logistical barriers to enrolling patients receiving dialysis | Build provider networks and partnerships to support trial conduct among patients receiving dialysis |

| Patient involvement | |

| Patients unaware of clinical trials or how to participate Patients with kidney disease are unaware that they are at risk for cardiovascular disease | Increase patient knowledge about the link between cardiovascular and kidney disease via educational campaigns coordinated by NIH and specialty organizations (e.g., ASN, NKF, ISN, ERA-EDTA) with support from dialysis providers and patient groups |

| Educate patients on trial participation via physicians, patient advocacy groups, social media, and other patients with kidney disease | |

| Develop registry of ongoing trials and provide mechanism for patients to determine eligibility and connect with study coordinator | |

| Patient concerns include fear of the unknown, risk of receiving placebo, polypharmacy, painful testing, inconvenience, and lack of time, sufficient compensation for participation, and communication of research results | Communicate trial results back to participants |

FDA, Food and Drug Administration; CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; NHLBI, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; NIDDK, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; ERA-EDTA, European Renal Association–European Dialysis and Transplant Association; HFSA, Heart Failure Society of America; KCVD, Council on the Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease; CRSA, Cardio-Renal Society of America; INI-CRCT, Investigation Network Initiative–Cardiovascular and Renal Clinical Trialists; CVCT, CardioVascular Clinical Trialists Forum; KDCT, Kidney Disease Clinical Trialists; NIH, National Institutes of Health; ASN, American Society of Nephrology; NKF, National Kidney Foundation; ISN, International Society of Nephrology.

Building the Business Case

Challenges

Patients with kidney disease represent a subgroup in which the pathophysiology of cardiovascular disease can differ from that of the general population (16), which could reduce the efficacy of a therapy if it targets a mechanism that may be less relevant in this subgroup. Additionally, patients with kidney disease have multiple comorbidities and are at risk for experiencing adverse events (17). Thus, trial sponsors with finite financial resources and competing priorities for investment may have concerns about supporting cardiovascular studies involving patients with kidney disease, particularly those with advanced disease, because this could potentially skew their efficacy and safety results and affect regulatory approval and product labeling. If trial sponsors collectively continue to exclude patients with advanced kidney disease from their cardiovascular trials, this may serve as a further disincentive for sponsors to deviate from this common practice.

Solutions

A business case must be made to research sponsors to articulate why patients with advanced kidney disease need to be involved in cardiovascular trials, highlighting the return on investment in this subgroup at high risk for cardiovascular events (1,2). The financial risk of including patients with advanced kidney disease into cardiovascular trials could be mitigated by utilization of regulatory and financial incentives that may be applicable to this population.

First, sponsors should consider early during development how existing FDA programs, such as Orphan Drug Designation, Breakthrough Therapy, Fast Track, Accelerated Approval, and Priority Review, could be leveraged to encourage cardiovascular trials that include patients with advanced kidney disease (18,19). For example, the development of surrogate cardiovascular end points for this population could open a path to accelerated approval, reducing time to market. Although not specifically related to a cardiovascular therapy, ongoing trials for IgA nephropathy and FSGS are evaluating proteinuria reduction as a surrogate end point to support regulatory submissions for accelerated approval (20,21). In addition, the development of lumasiran, the first FDA-approved treatment for primary hyperoxaluria type 1, was facilitated by Orphan Drug and Breakthrough Therapy designations and involved successful collaboration among multiple stakeholders, including industry, FDA, physicians, and patients (22). KHI has championed publications that have fostered these development efforts and provides a forum for multidisciplinary collaboration (23,24).

In addition, financial incentives, such as market exclusivity extensions for products that have demonstrated efficacy in patients with advanced kidney disease, could also encourage their inclusion in trials, although this would require new legislation. Engaging Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and other payers early in the development process could also provide insight into how to lay the groundwork for successfully bringing a new cardiovascular therapy for patients with advanced kidney disease to market and reduce concerns about coverage or reimbursement after approval. Finally, incorporating feedback from patients with kidney disease throughout the development process can add financial value by potentially avoiding costly protocol amendments and improving enrollment, adherence to the intervention, and retention in the trial (25).

Study Design and Implementation

Challenges

Safety Concerns

Safety concerns are viewed as a major barrier to including patients with advanced kidney disease in cardiovascular trials by trial sponsors, investigators, and patients. Patients with kidney disease suffer from multiple comorbidities and take multiple medications (26), which places them at risk for adverse events, drug interactions, nonadherence to the intervention, and withdrawal from the trial.

Trial sponsors may be reluctant to design cardiovascular studies that include this subgroup given the additional financial and logistical burden of safety monitoring and reporting and the potential reduction in data quality due to poor adherence, study drug discontinuation, and study dropout. Investigators may likewise be concerned about this increased burden and may be reluctant to enroll patients with advanced kidney disease if the investigational product affects eGFR or may exacerbate complications of kidney disease, such as hyperkalemia. Patients may be deterred from trial participation due to concerns that the intervention could worsen their kidney disease or cause adverse effects.

Efficacy Concerns

Because the pathophysiology of cardiovascular disease in patients with kidney disease can differ from that of the general population (16), a treatment may lack efficacy or have a smaller effect size in this subgroup, skewing the overall result of a trial toward the null. Additionally, the outcomes of interest may differ for some kidney disease populations. For example, arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death are leading causes of death among patients with kidney failure (27) and may be more relevant than coronary heart death in some situations. Additionally, heart failure end points that are suitable in the general population may need to be modified for studies in patients with kidney failure to address unique challenges related to fluid management (28 –30). Thus, end points used in the general population may not be as relevant for patients with advanced kidney disease, and there is a need for the development of end points that may be more appropriate for this subgroup (28).

Lack of Innovative Protocol Designs

When designing new trials, sponsors may use templates from previous trials that excluded patients with advanced kidney disease (7,8). These protocols may not have involved input from nephrologists who have the greatest knowledge and expertise regarding the unique characteristics of patients with kidney disease.

Recruitment Concerns

Among all patients with cardiovascular disease, a relatively small proportion has advanced kidney disease, particularly kidney failure (27). Absent specific efforts to target patients in this subgroup, investigators may be unable to recruit and enroll sufficient numbers of patients to draw meaningful conclusions about this population.

Solutions

Manage Safety Concerns

Adverse events are anticipated to be common among patients with advanced kidney disease, and in some cases, their exclusion may be justified due to safety concerns related to a particular drug or device. However, sponsors should consider whether there are aspects of trial design that could mitigate safety risks. For example, the SONAR trial of atrasentan in diabetic patients with kidney disease incorporated a novel design that excluded participants with fluid retention to minimize risk of heart failure (31). Sponsors may consider adopting such an approach that excludes participants who are at risk for experiencing adverse events. In addition, protocols can prohibit or restrict use of medications commonly used in this population that interact with the investigational product. If the intervention affects eGFR, sponsors should understand the mechanism, time course of the effect, reversibility, and implications for longer-term kidney function, and they should provide appropriate education to investigators. If the intervention may exacerbate complications of kidney disease (e.g., hyperkalemia), sponsors and investigators can develop strategies to manage these risks (e.g., noninvasive potassium monitoring and potassium-lowering agents). Patient input on strategies to mitigate safety risks and maximize adherence to intervention and study participation should also be incorporated into study design and implementation. It is possible that measures to mitigate safety risks could increase costs for sponsors, but investments in such safeguards should ideally be balanced by avoidance of adverse events and undesirable downstream consequences, such as study drug discontinuation and study dropout.

Require Justification for Exclusion of Patients with Advanced Kidney Disease

Although excluding patients with advanced kidney disease may be warranted in some settings, the rationale for exclusion may not be clear or justified in all cases. Trial sponsors should carefully consider whether there is a strong rationale to exclude patients with advanced kidney disease, and individuals involved in trial conduct, including investigators, regulatory authorities, and patients, should routinely question exclusions on the basis of level of kidney function. Requiring justification for exclusion of patients with advanced kidney disease could serve to mitigate unnecessary exclusion due to concerns about potential effect on efficacy results.

Innovative Protocol Design

To mitigate sponsor concerns over potentially diluting efficacy due to the inclusion of patients with advanced kidney disease in cardiovascular trials conducted in the general population, sponsors could be given the option of enrolling patients with an eGFR below a certain threshold but excluding them from key efficacy end point analyses. Given the relatively low prevalence of advanced kidney disease, it may be challenging to enroll sufficient numbers of patients to draw firm conclusions; however, this approach would allow collection of some efficacy and safety information in this subgroup rather than none.

Another option would be to conduct a dedicated cardiovascular trial for patients with advanced kidney disease in parallel with a cardiovascular trial in the general population that excludes patients below a certain eGFR cutoff. This option may be particularly relevant if it is necessary to use cardiovascular end points that are tailored to patients with advanced kidney disease. As kidney disease advances, there is a shift toward an increasing burden of nonatherosclerotic disease (e.g., arrythmias and sudden cardiac death) versus atherosclerotic disease (e.g., coronary artery disease and ischemic stroke), and end points should be selected as appropriate to the study population (32).

Additionally, the end point definitions themselves may require modification. For example, in a trial evaluating heart failure events among participants receiving hemodialysis, the standard definition of a heart failure end point event may not be optimal. It may be challenging to determine whether signs and symptoms of volume overload are attributable to heart failure or kidney failure, which may be related to missed hemodialysis sessions, dry weight overestimation, or lack of adherence to diet and fluid restrictions (28). Such a trial could consider using the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative–proposed classification of heart failure in patients with kidney failure, which takes into account response of symptoms to RRT/ultrafiltration, if the staging system undergoes the appropriate prospective validation (29). Cardiovascular and kidney trialists must continue collaborating on the development of standardized cardiovascular outcome definitions for patients with advanced kidney disease and kidney failure.

Nephrologists are optimally positioned to advise on how to tailor cardiovascular trial protocols to facilitate involvement of patients with advanced kidney disease, so consulting nephrologists to guide the design and implementation of cardiovascular trials involving this population is essential.

Recruitment

Recruitment of patients with kidney disease into cardiovascular trials may be facilitated by seeking guidance from such patients on how to optimize recruitment strategies. Obtaining patient feedback on study materials (e.g., protocols) may help to ensure that study procedures will not be a deterrent to enrollment. Additionally, creation of registries for patients with kidney disease—a “virtual pool” of potential participants who may be amenable to participating in cardiovascular trials—may also support recruitment efforts. Best practices from cardiovascular trials that have been able to successfully enroll patients with stages 4 and 5 CKD (e.g., SHARP and ISCHEMIA-CKD) should be leveraged (33,34).

Clinical Trial Culture in Nephrology

Challenges

Current Culture

In addition to addressing challenges with financial concerns and study design and implementation, there is a compelling need for a broader mission to transform nephrology into an “on-study” culture in which trial participation is the norm and not the exception. The number and quality of trials in nephrology continue to be lower than that of other specialties (4 –6), and until recently, there has been limited investment in drug development for treatment of kidney disease. Recently published major trials (CREDENCE, DAPA-CKD, and FIDELIO-DKD) and ongoing trials involving patients with kidney disease point to the growing clinical trial enterprise within the field of nephrology (11 –13,35). However, because trials are not widely part of routine practice, nephrologists may be less familiar with them and may also face challenges with communicating the value of trial participation within their organizations.

Lack of Infrastructure

Nephrology lags behind other fields, such as oncology and cardiology, in terms of the infrastructure needed to support conducting clinical trials (36,37). There are few incentives for nephrologists to participate in trials and relatively limited numbers of established sites and investigators with experience enrolling patients with advanced kidney disease.

Enrollment Challenges

One topic raised at the stakeholder workshop (and receiving little attention in publications) is the practical concern of burden to site coordinators. Patients with advanced kidney disease are justifiably perceived by site coordinators to require more time and effort due to a higher number of expected reportable adverse events. Given that there is not additional compensation from the sponsor for enrolling patients with advanced kidney disease, there is essentially a disincentive for site coordinators to enroll such individuals.

For patients receiving dialysis, enrollment requires partnerships with dialysis organizations, posing financial and logistical barriers, such as the need for staff to perform research activities and disruptions to treatments. The RENAL-AF trial (38), which evaluated the safety of apixaban versus warfarin in patients on hemodialysis with atrial fibrillation, was terminated early for slow enrollment, exemplifying the daunting challenges facing researchers conducting cardiovascular clinical trials in patients on dialysis.

Patient Involvement

Patients overwhelmingly express a willingness to participate in cardiovascular trials, citing the importance of this issue to people with kidney disease and a desire to help contribute knowledge to the field. However, patients with kidney disease may not be aware that trials are happening or how to participate. Additionally, patients with kidney disease may be unaware that they are at risk for cardiovascular disease. In the Wearable Cardioverter Defibrillator in Hemodialysis Patients trial (39), which was terminated for slow enrollment, a recurring refrain from patients considering trial participation was, “What do you mean I am at risk for sudden cardiac death? If that’s true, why didn’t my nephrologist tell me?”

Despite their willingness to participate, patients expressed some concerns. In addition to the safety concerns discussed above, other concerns included fear of the unknown, risk of receiving placebo, polypharmacy, painful testing, inconvenience, and lack of time and sufficient compensation for participation. Patients also expressed a strong desire for the results of research studies to be communicated back to them.

Solutions

Greater participation of patients with kidney disease in cardiovascular trials will require a cultural change within nephrology in which trial participation is broadly supported. To this end, there are several strategies aimed at facilitating physician and patient engagement in trials that could help move nephrology toward the “on-study” mindset that is more common in other specialties.

Physician Engagement

Physician participation in trials could be supported through financial and other incentives. For example, participation of academic investigators could be enhanced if nephrology and cardiology division leadership created protected time for trial activities and recognized their intrinsic value. Continuing medical education credit could also be offered for trial-related efforts. Additionally, enhancing government funding across multiple relevant institutes, subspecialty societies, and industry-sponsored funding could expand opportunities to conduct cardiovascular trials involving patients with kidney disease. Providing training in trial planning and execution, particularly among trainees and junior investigators, could also help to ensure a steady pipeline of researchers capable of conducting trials. Shared resources, such as papers and presentations, should be developed to support nephrologists’ involvement as principal investigators and to spur discussions with health systems.

Collaboration

Numerous recent papers have called for specific training in cardiorenal medicine and closer collaboration between nephrologists and cardiologists (40 –43). A larger community of nephrologists and cardiologists must be created, leveraging existing professional organizations. Attendance at multidisciplinary meetings and academic meetings outside of one’s specialty should also be encouraged to enhance crossfertilization of ideas, along with coordinating efforts across existing trial networks.

Building provider networks and partnerships among other stakeholders would also help create the infrastructure needed to support trial conduct among patients receiving dialysis and greater engagement from nephrologists. For example, a network of dialysis providers could share resources (e.g., research coordinators) to facilitate trials.

Patient Engagement

In order to emphasize the clinical importance of cardiovascular disease, patients with kidney disease must be informed about the link between kidney and heart disease. Educational campaigns, coordinated by the National Institutes of Health and specialty organizations with support from dialysis providers and patient groups, could aid in these efforts. Patient engagement could also be strengthened through education about trial participation by personal physicians, patient advocacy groups, social media, and other patients with kidney disease. Compensation to sites to incentivize enrollment of patients with advanced kidney disease should be considered.

The creation of a trial registry could also help allay patient concerns about lack of information about study participation opportunities. The registry would include a list of ongoing trials targeted for study populations with kidney disease, including cardiovascular trials, and would be interactive such that an interested patient could easily obtain information about a trial, answer a screening questionnaire to determine eligibility, and indicate a desire to be contacted by a study coordinator. Such a registry would empower patients to be active partners in trial participation, improve the efficiency and costs of recruitment, and ameliorate concerns regarding investigator access to particular groups of patients with kidney disease, such as those receiving dialysis. Finally, trial results should be communicated back to those who have participated in the trial, maintaining patient involvement from start to finish and creating a greater sense of engagement.

Call to Action

The persistent under-representation of patients with kidney disease in cardiovascular trials has led to insufficient evidence to guide optimal management of cardiovascular disease in this population. Our charge was to identify barriers to including patients with kidney disease in cardiovascular trials, with an emphasis on those with advanced disease, and strategies to overcome these hurdles. Many of the topics discussed in this paper are broadly applicable to nephrology trials in general. However, the challenges we identified may be magnified among the subgroup of patients with kidney disease and cardiovascular disease, given their high mortality and morbidity.

Our work group identified financial, methodologic, operational, and cultural barriers to greater inclusion of patients with advanced kidney disease in cardiovascular trials, but we believe these barriers are not insurmountable. Strategies to overcome them include building a business case with regulatory and financial incentives, improving study design and implementation with greater physician and patient engagement, and creating an “on-study” culture in nephrology akin to that of other specialties. Implementation of the proposed solutions will require a multidisciplinary effort involving a variety of stakeholders, including academia, industry, regulatory agencies, patients, and government and specialty organizations in the nephrology and cardiology community. Collectively, these strategies can increase the available data for managing cardiovascular disease among patients with kidney disease and allow providers to make more informed treatment decisions in this important subgroup.

Disclosures

ASN requires authors to disclose any financial relationship or commitment for the previous 36 months held by the author and any spouse/partner of the author. However, it was recently brought to our attention that the disclosures provided by Dr. Peter A. McCullough were incomplete as provided here: “P.A. McCullough is currently employed by Texas A&M Medical Center and has consultancy agreements with Akebia, all outside of the submitted work.” According to the CMS Open Payments System, the following are Dr. McCullough's disclosures for the previous 36 months:

P.A. McCullough reports receiving consulting fees from Abbott Laboratories, Aegerion Pharmaceuticals Inc., Akebia, Amgen Inc., AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, Baxter Healthcare, Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH, CHF Solutions Inc, Edwards Lifesciences Corporation, Eli Lilly and Company, GE HEALTHCARE, Instrumentation Laboratory Company, Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc, Keryx Biopharmaceuticals Inc., Mallinckrodt Enterprises LLC, Medicure Pharma Inc., Merck Sharp & Dohme Corporation, Novartis Pharma AG, Novo Nordisk, NxStage Medical Inc., Quidel Corporation, and Sanofi and Genzyme US Companies; compensation for services other than consulting, including serving as faculty or as a speaker at a venue other than a continuing education program, from Abbott Laboratories, Amgen Inc., AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc., Edwards Lifesciences Corporation, GE HEALTHCARE, Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc, Novo Nordisk Inc, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., and Sanofi and Genzyme US Companies; food, beverage, travel, or lodging expenses from Abbott Laboratories, Aegerion Pharmaceuticals Inc., Amgen Inc., AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, Baxter Healthcare, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc., Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc., Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, CHIESI USA INC., Edwards Lifesciences Corporation, Eli Lilly and Company, E.R. Squibb & Sons L.L.C., GE HEALTHCARE, Instrumentation Laboratory Company, Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc, Keryx Biopharmaceuticals Inc., Lexicon Pharmaceuticals Inc., Mallinckrodt Enterprises LLC, Medicure Pharma Inc., Merck Sharp & Dohme Corporation, Novartis, Novo Nordisk Inc, NxStage Medical Inc., Otsuka America Pharmaceutical Inc., Pfizer Inc., Quidel Corporation, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., Sanofi and Genzyme US Companies, and ZOLL Services LLC (A/K/A ZOLL LifeCor Corp); research payments from Abbott Laboratories, AbbVie Inc., and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc.; and associated research payments from AbbVie Inc., Aegerion Pharmaceuticals Inc., Amgen Inc., AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, Boehringer Ingelheim Corporate Center GmbH, GE HEALTHCARE, Novo Nordisk AS, and Sanofi and Genzyme US Companies. C. Chauhan has done two educational videos on heart failure with preserved ejection fraction within the last 2 years for Novartis. She received $900 for the first and no reimbursement for the second. She is professionally affiliated with the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the Heart Failure Society of America, and the International Society for Quality of Life. C. Chauhan is patient advocate, Academic and Community Research United, 2011 to present; patient trialist forum moderator, Cardiovascular Clinical Trialists Forum, 2017 to present; member, Patiromer for the Management of Hyperkalemia in Subjects Receiving RAASi Medications for the Treatment of Heart Failure Trial Executive Committee, 2019 to present; patient representative, FDA Oncologic Drugs Advisor Committee (reimbursed position); member, Patient Engagement Advisory Committee, FDA (reimbursed position), 2017 to present; member, Heart Failure Collaboratory, 2018 to present; member, Kansas Cancer Coalition, 2014 to present; member, KHI Working Group, 2017 to present; chair, Mayo Clinic Breast Cancer Specialized Program of Research Excellence Advocacy Advisory Committee, 2010 to present; member, Patient-Centered Involvement in Evaluating the Effectiveness of Treatments External Advisory Committee, 2006 to present; member, Pragmatic Randomized Trial of Proton vs. Photon Therapy for Patients With Non-Metastatic Breast Cancer: A Radiotherapy Comparative Effectiveness Consortium Trial Executive Committee, 2016 to present; and member, Research Advocacy Network Advisory Board, 2004 to present. B. Gillespie is currently employed by Covance by LabCorp; reports having ownership in LabCorp; reports receiving honoraria from NephCure Gateway Initiative; and reports serving as a scientific advisor or member of the CardioRenal Society of America Board of Directors, the KHI Board of Directors, and the National Kidney Diseases CKD Registry steering committee and scientific advisory board, all outside of the submitted work. C.A. Herzog is currently employed by Hennepin Healthcare System; reports receiving grants from Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (National Institutes of Health), Relypsa, and the University of British Columbia; reports receiving honoraria from the American College of Cardiology and UpToDate (writing royalties); reports serving as a consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Corvidia, DiaMedica, FibroGen, Janssen, Merck, NxStage, OxThera, Pfizer, Relypsa, and the University of Oxford; reports serving as a scientific advisor or member of the American Heart Journal Editorial Board, KHI, and Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes Planning Committee for CKD, Heart and Vasculature conference series; and has stock in Boston Scientific, General Electric, Johnson & Johnson, and Merck, all outside of the submitted work. J.H. Ishida was employed by the University of California, San Francisco during the initiation and development of this project and is currently employed by and has ownership interest in Gilead Sciences, outside of the submitted work. J.H. Ishida is KHI Work Group Co-Chair. M.A. Malley and M. West are currently employed by the American Society of Nephrology. P.A. McCullough is currently employed by Texas A&M Medical Center and has consultancy agreements with Akebia, all outside of the submitted work. A. Romero was employed by and had ownership interest in Relypsa, a Vifor Pharma Group Company at the time of participation in the KHI Work Group. He is currently employed by and has ownership interest in Chinook Therapeutics, and reports receiving honoraria from Respira Therapeutics, all outside of the submitted work. P. Rossignol is currently employed by the University of Lorraine Clinical Investigation Center–Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale–Centre Hospitalier Régional Universitaire of Nancy; reports serving as a consultant for Idorsia; reports receiving honoraria from AstraZeneca, Bayer, CVRx, Fresenius, Grunenthal, Novartis, NovoNordisk, Relypsa, Servier, Stealth Peptides, and Vifor Fresenius Medical Care Renal Pharma; reports receiving travel grants from AstraZeneca, Bayer, CVRx, Novartis, and Vifor Fresenius Medical Care Renal Pharma; reports receiving grants and personal fees from Fresenius, nonfinancial support from Fresenius, personal fees from KBP, personal fees from Sequana Medical, and personal fees from Sanofi; reports receiving research funding from Relypsa and Vifor Fresenius Medical Care Renal Pharma; and reports having ownership interest in G3P and being a cofounder of CardioRenal. P. Rossignol reports serving as an American Society of Nephrology KHI work group board member: Understanding and Overcoming the Challenges to Involving Patients with Kidney Disease in Cardiovascular Trials; a working group board member for European Renal and Cardiovascular Medicine European Renal Association–European Dialysis and Transplant Association, 2021–2023; an European Society of Hypertension “hypertension and the kidney” working group board member since 2016; and a working group board member Heart Failure Association, Cardio renal and translational, 2016–2020, all outside of the submitted work. D.C. Wheeler is currently employed by the University College London; reports serving as a consultant for Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelhiem, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Mundipharma, Napp, Tricida, and Vifor Fresenius; reports receiving honoraria from Amgen, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelhiem, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Merck, Mundipharma, Napp, Ono Pharma, Reata, Sharp and Dohme, and Vifor Fresenius; and reports serving as an Honorary Professorial Fellow of the George Institute for Global Health and a scientific advisor or member of KHI, all outside of the submitted work. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This work was supported by KHI, which is partially funded by US Food and Drug Administration grant 5R18FD005283-07 and the American Society of Nephrology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Dr. Aliza Thompson and Dr. Kimberly Smith from US FDA for their thoughtful guidance on the development of this paper. The authors also acknowledge the contributions of the workshop attendees to furthering discussion of the issues outlined in this paper.

This work was supported by KHI, a public-private partnership between the American Society of Nephrology, US FDA, and >100 member organizations and companies to enhance patient safety and foster innovation in kidney disease. KHI funds were used to defray costs incurred during the conduct of the project, including project management support, which was provided by American Society of Nephrology staff members Mrs. Meaghan A. Malley, Ms. Elle Silverman, and Mrs. Melissa West. There was no honorarium or other financial support provided to KHI work group members. The authors of this paper had final review authority and are fully responsible for its content. KHI makes every effort to avoid actual, potential, or perceived conflicts of interest that may arise as a result of industry relationships or personal interests among the members of the work group. More information on KHI, the work group, or the conflict of interest policy can be found at www.kidneyhealthinitiative.org.

The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policies of any KHI member organization, FDA, the US Department of Veterans Affairs, or the US Department of Health and Human Services, nor does any mention of trade names, commercial practices, or organization imply endorsement by the US Government.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.17561120/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. Expert stakeholder poll respondent characteristics.

Supplemental Table 2. Patient and care partner poll respondent characteristics.

Supplemental Appendix 1. Expert stakeholder poll questions.

Supplemental Appendix 2. Patient and care partner poll questions.

References

- 1.Coca SG, Krumholz HM, Garg AX, Parikh CR: Underrepresentation of renal disease in randomized controlled trials of cardiovascular disease. JAMA 296: 1377–1384, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Charytan D, Kuntz RE: The exclusion of patients with chronic kidney disease from clinical trials in coronary artery disease. Kidney Int 70: 2021–2030, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strippoli GF, Craig JC, Schena FP: The number, quality, and coverage of randomized controlled trials in nephrology. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 411–419, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palmer SC, Sciancalepore M, Strippoli GF: Trial quality in nephrology: How are we measuring up? Am J Kidney Dis 58: 335–337, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inrig JK, Califf RM, Tasneem A, Vegunta RK, Molina C, Stanifer JW, Chiswell K, Patel UD: The landscape of clinical trials in nephrology: A systematic review of ClinicalTrials.gov. Am J Kidney Dis 63: 771–780, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chatzimanouil MKT, Wilkens L, Anders HJ: Quantity and reporting quality of kidney research. J Am Soc Nephrol 30: 13–22, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Konstantinidis I, Nadkarni GN, Yacoub R, Saha A, Simoes P, Parikh CR, Coca SG: Representation of patients with kidney disease in trials of cardiovascular interventions: An updated systematic review. JAMA Intern Med 176: 121–124, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maini R, Wong DB, Addison D, Chiang E, Weisbord SD, Jneid H: Persistent underrepresentation of kidney disease in randomized, controlled trials of cardiovascular disease in the contemporary era. J Am Soc Nephrol 29: 2782–2786, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishida JH, Johansen KL: Exclusion of patients with kidney disease from cardiovascular trials. JAMA Intern Med 176: 124–125, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Archdeacon P, Shaffer RN, Winkelmayer WC, Falk RJ, Roy-Chaudhury P: Fostering innovation, advancing patient safety: The Kidney Health Initiative. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1609–1617, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, Bompoint S, Heerspink HJL, Charytan DM, Edwards R, Agarwal R, Bakris G, Bull S, Cannon CP, Capuano G, Chu PL, de Zeeuw D, Greene T, Levin A, Pollock C, Wheeler DC, Yavin Y, Zhang H, Zinman B, Meininger G, Brenner BM, Mahaffey KW; CREDENCE Trial Investigators: Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 380: 2295–2306, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heerspink HJL, Stefánsson BV, Correa-Rotter R, Chertow GM, Greene T, Hou FF, Mann JFE, McMurray JJV, Lindberg M, Rossing P, Sjöström CD, Toto RD, Langkilde AM, Wheeler DC; DAPA-CKD Trial Committees and Investigators: Dapagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 383: 1436–1446, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bakris GL, Agarwal R, Anker SD, Pitt B, Ruilope LM, Rossing P, Kolkhof P, Nowack C, Schloemer P, Joseph A, Filippatos G; FIDELIO-DKD Investigators: Effect of finerenone on chronic kidney disease outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 383: 2219–2229, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bakris G, Oshima M, Mahaffey KW, Agarwal R, Cannon CP, Capuano G, Charytan DM, de Zeeuw D, Edwards R, Greene T, Heerspink HJL, Levin A, Neal B, Oh R, Pollock C, Rosenthal N, Wheeler DC, Zhang H, Zinman B, Jardine MJ, Perkovic V: Effects of canagliflozin in patients with baseline eGFR <30 ml/min per 1.73 m2: Subgroup analysis of the randomized CREDENCE trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 1705–1714, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zoungas S, Polkinghorne KR: Are SGLT2 inhibitors safe and effective in advanced diabetic kidney disease? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 1694–1695, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tomey MI, Winston JA: Cardiovascular pathophysiology in chronic kidney disease: Opportunities to transition from disease to health. Ann Glob Health 80: 69–76, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zoccali C, Blankestijn PJ, Bruchfeld A, Capasso G, Fliser D, Fouque D, Goumenos D, Ketteler M, Massy Z, Rychlık I, Jose Soler M, Stevens K, Spasovski G, Wanner C: Children of a lesser god: Exclusion of chronic kidney disease patients from clinical trials. Nephrol Dial Transplant 34: 1112–1114, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.US Food and Drug Administration: Fast track, breakthrough therapy, accelerated approval, priority review, 2018. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/patients/learn-about-drug-and-device-approvals/fast-track-breakthrough-therapy-accelerated-approval-priority-review. Accessed December 29, 2020

- 19.US Food and Drug Administration: Designating an orphan product: Drugs and biological products, 2020. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/industry/developing-products-rare-diseases-conditions/designating-orphan-product-drugs-and-biological-products. Accessed December 29, 2020

- 20.Travere Therapeutics: Press release: Retrophin announces enrollment of first 280 patients in pivotal phase 3 PROTECT study of sparsentan in IgA nephropathy, 2020. Available at: https://ir.travere.com/news-releases/news-release-details/retrophin-announces-enrollment-first-280-patients-pivotal-phase. Accessed December 29, 2020

- 21.Travere Therapeutics: Press release: Travere therapeutics announces completion of patient enrollment in pivotal phase 3 DUPLEX study of sparsentan in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, 2020. Available at: https://ir.travere.com/news-releases/news-release-details/travere-therapeutics-announces-completion-patient-enrollment. Accessed December 29, 2020

- 22.US Food and Drug Administration: FDA approves first drug to treat rare metabolic disorder, 2020. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-drug-treat-rare-metabolic-disorder#:∼:text=Today%2C%20the%20U.S.%20Food%20and%2C%20a%20rare%20genetic%20disorder. Accessed December 29, 2020

- 23.Thompson A, Carroll K, A Inker L, Floege J, Perkovic V, Boyer-Suavet S, W Major R, I Schimpf J, Barratt J, Cattran DC, S Gillespie B, Kausz A, W Mercer A, Reich HN, H Rovin B, West M, Nachman PH: Proteinuria reduction as a surrogate end point in trials of IgA nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 469–481, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Milliner DS, McGregor TL, Thompson A, Dehmel B, Knight J, Rosskamp R, Blank M, Yang S, Fargue S, Rumsby G, Groothoff J, Allain M, West M, Hollander K, Lowther WT, Lieske JC: End points for clinical trials in primary hyperoxaluria. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 1056–1065, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levitan B, Getz K, Eisenstein EL, Goldberg M, Harker M, Hesterlee S, Patrick-Lake B, Roberts JN, DiMasi J: Assessing the financial value of patient engagement: A quantitative approach from CTTI’s patient groups and clinical trials project. Ther Innov Regul Sci 52: 220–229, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmidt IM, Hübner S, Nadal J, Titze S, Schmid M, Bärthlein B, Schlieper G, Dienemann T, Schultheiss UT, Meiselbach H, Köttgen A, Flöge J, Busch M, Kreutz R, Kielstein JT, Eckardt KU: Patterns of medication use and the burden of polypharmacy in patients with chronic kidney disease: The German Chronic Kidney Disease study. Clin Kidney J 12: 663–672, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.United States Renal Data System : 2017 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2017. Available at: https://www.usrds.org/annual-data-report/previous-adrs/. Accessed December 29, 2020

- 28.Rossignol P, Agarwal R, Canaud B, Charney A, Chatellier G, Craig JC, Cushman WC, Gansevoort RT, Fellström B, Garza D, Guzman N, Holtkamp FA, London GM, Massy ZA, Mebazaa A, Mol PGM, Pfeffer MA, Rosenberg Y, Ruilope LM, Seltzer J, Shah AM, Shah S, Singh B, Stefánsson BV, Stockbridge N, Stough WG, Thygesen K, Walsh M, Wanner C, Warnock DG, Wilcox CS, Wittes J, Pitt B, Thompson A, Zannad F: Cardiovascular outcome trials in patients with chronic kidney disease: Challenges associated with selection of patients and endpoints. Eur Heart J 40: 880–886, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chawla LS, Herzog CA, Costanzo MR, Tumlin J, Kellum JA, McCullough PA, Ronco C; ADQI XI Workgroup: Proposal for a functional classification system of heart failure in patients with end-stage renal disease: Proceedings of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) XI workgroup. J Am Coll Cardiol 63: 1246–1252, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rossignol P, Pitt B, Thompson A, Zannad F: Roadmap for cardiovascular prevention trials in chronic kidney disease. Lancet 388: 1964–1966, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heerspink HJL, Parving HH, Andress DL, Bakris G, Correa-Rotter R, Hou FF, Kitzman DW, Kohan D, Makino H, McMurray JJV, Melnick JZ, Miller MG, Pergola PE, Perkovic V, Tobe S, Yi T, Wigderson M, de Zeeuw D; SONAR Committees and Investigators: Atrasentan and renal events in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease (SONAR): A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial [published correction appears in Lancet 393:1936, 2019 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30939-0]. Lancet 393: 1937–1947, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wanner C, Amann K, Shoji T: The heart and vascular system in dialysis. Lancet 388: 276–284, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baigent C, Landray MJ, Reith C, Emberson J, Wheeler DC, Tomson C, Wanner C, Krane V, Cass A, Craig J, Neal B, Jiang L, Hooi LS, Levin A, Agodoa L, Gaziano M, Kasiske B, Walker R, Massy ZA, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Krairittichai U, Ophascharoensuk V, Fellström B, Holdaas H, Tesar V, Wiecek A, Grobbee D, de Zeeuw D, Grönhagen-Riska C, Dasgupta T, Lewis D, Herrington W, Mafham M, Majoni W, Wallendszus K, Grimm R, Pedersen T, Tobert J, Armitage J, Baxter A, Bray C, Chen Y, Chen Z, Hill M, Knott C, Parish S, Simpson D, Sleight P, Young A, Collins R; SHARP Investigators: The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with simvastatin plus ezetimibe in patients with chronic kidney disease (Study of Heart and Renal Protection): A randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 377: 2181–2192, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bangalore S, Maron DJ, O’Brien SM, Fleg JL, Kretov EI, Briguori C, Kaul U, Reynolds HR, Mazurek T, Sidhu MS, Berger JS, Mathew RO, Bockeria O, Broderick S, Pracon R, Herzog CA, Huang Z, Stone GW, Boden WE, Newman JD, Ali ZA, Mark DB, Spertus JA, Alexander KP, Chaitman BR, Chertow GM, Hochman JS; ISCHEMIA-CKD Research Group: Management of coronary disease in patients with advanced kidney disease. N Engl J Med 382: 1608–1618, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.NephCure Kidney International: Trials & research, 2020. Available at: https://kidneyhealthgateway.com/trials-research/. Accessed December 29, 2020

- 36.Perkovic V, Craig JC, Chailimpamontree W, Fox CS, Garcia-Garcia G, Benghanem Gharbi M, Jardine MJ, Okpechi IG, Pannu N, Stengel B, Tuttle KR, Uhlig K, Levey AS: Action plan for optimizing the design of clinical trials in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 7: 138–144, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baigent C, Herrington WG, Coresh J, Landray MJ, Levin A, Perkovic V, Pfeffer MA, Rossing P, Walsh M, Wanner C, Wheeler DC, Winkelmayer WC, McMurray JJV; KDIGO Controversies Conference on Challenges in the Conduct of Clinical Trials in Nephrology Conference Participants: Challenges in conducting clinical trials in nephrology: Conclusions from a Kidney Disease-Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) controversies conference. Kidney Int 92: 297–305, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.ClinicalTrials.gov: Trial to evaluate anticoagulation therapy in hemodialysis patients with atrial fibrillation (RENAL-AF), 2020. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02942407. Accessed December 29, 2020

- 39.ClinicalTrials.gov: Wearable cardioverter defibrillator in hemodialysis patients (WED-HED) study, 2020. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02481206. Accessed December 29, 2020

- 40.Kazory A, McCullough PA, Rangaswami J, Ronco C: Cardionephrology: Proposal for a futuristic educational approach to a contemporary need. Cardiorenal Med 8: 296–301, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ronco C, Ronco F, McCullough PA: A call to action to develop integrated curricula in cardiorenal medicine. Rev Cardiovasc Med 18: 93–99, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rangaswami J, Mathew RO, McCullough PA: Resuscitation for the specialty of nephrology: Is cardionephrology the answer? Kidney Int 93: 25–26, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zannad F, Rossignol P: Cardiorenal syndrome revisited. Circulation 138: 929–944, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.