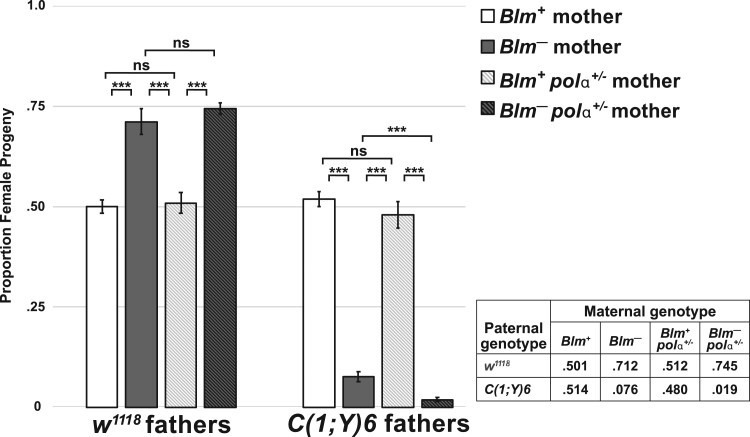

Figure 7.

A genetic reduction of Polα exacerbates the sex-bias amongst progeny from Blm– mothers. The proportion of female progeny from w1118 (Blm+) and Blm (Blm–) mothers is taken from Figure 2 and compared with Blm+ and Blm– mothers that also package reduced Polα in their embryos (Blm+ polα+/− and Blm– polα+/−, respectively). In a Blm+ background, mothers who provide functional Blm to their eggs are not affected by a genetic reduction in Polα (no significant difference between Blm+ and Blm+ polα+/− mothers in the progeny sex-bias in crosses to w1118 or C(1;Y)6 fathers; P > 0.05 for both comparisons). However, in a Blm background (Blm– mothers), reducing Polα further exacerbates the significant progeny sex-bias that favors the class of flies that inherits less repetitive DNA content. In the crosses involving w1118 fathers, the female progeny sex-bias was more pronounced, but did not reach statistical significance (P > 0.05). However, in crosses involving C(1;Y)6 fathers, the exacerbation of the sex-bias favoring male progeny is significantly different compared with the progeny from Blm– mothers (P < 0.0001). The number of replicates and the total number of flies counted for Blm+ polα+/− progeny were as follows: w1118 fathers (n = 25; 2439); C(1;Y)6 fathers (n = 17; 1818). The number of replicates and the total number of flies counted for Blm– polα+/− progeny were as follows: w1118 fathers (n = 46; 3265); C(1;Y)6 fathers (n = 45; 2929). ns, not significantly different (P > 0.05); ***P < 0.0001. All P-values were calculated with one-way ANOVA tests followed by post hoc comparisons of the observed proportions of female progeny to one another. These data were not normally distributed, and some crosses had small sample sizes (n < 30); however, our results were robust to nonparametric statistical approaches as well.