Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to investigate the genetic determinants of fusidic acid (FA) resistance in MRSA isolated from patients in Kuwait hospitals.

Methods

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of FA was tested with E-test strips. Genetic determinants of FA were determined by PCR and DNA microarray. Staphylococcal protein A gene (spa) typing and DNA microarray analysis were used to study their genetic backgrounds.

Results

The FA MIC ranged from 2 mg/L to >256 mg/L. Of the 97 isolates, 79 (81.4%) harbored fusC, 14 isolates harbored fusA mutations (fusA), and 4 isolates harbored fusB. Isolates with fusA mutations expressed high FA MIC (MIC >256 mg/L), whereas those with fusC and fusB expressed low FA MIC (MIC 2–16 mg/L). The isolates belonged to 23 spa types and 12 clonal complexes (CCs). The major spa types were t688 (n = 25), t311 (n = 14), t860 (n = 8), and t127 (n = 6) which constituted 54.6% of the isolates. The 12 CCs were CC1, CC5, CC8, CC15, CC22, CC80, CC88, and CC97 with CC5 (45.6%) and CC97 (13.2%) as the dominant CCs.

Conclusions

The MRSA isolates belonged to diverse genetic backgrounds with the majority carrying the fusC resistance determinants. The high prevalence of FA resistance belonging to diverse genetic backgrounds warrants a review of FA usage in the country to preserve its therapeutic benefits.

Keywords: Fusidic acid resistance, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Spa typing, DNA microarray

Highlights of the Study

Three genetic determinants, fusA mutation (fusA), fusB, and fusC, were responsible for fusidic acid resistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from Kuwait hospitals.

The majority of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates carried fusC.

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains belonged to diverse genetic backgrounds.

The high prevalence of fusidic acid-resistant methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus calls for a review of fusidic acid usage to preserve the therapeutic benefit of the antibiotic.

Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus is an opportunistic bacterial pathogen that is capable of causing a wide range of infections, including superficial skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs), pneumonia, bloodstream infections, and bone and joint, respiratory tract, and gastrointestinal tract as well as urinary tract infections [1, 2, 3]. Uncomplicated SSTIs are often treated with topical antibiotics such as fusidic acid (FA) and mupirocin [1, 2]. Topical antibiotics offer effective treatment options for SSTIs because the antibiotics are localized, well tolerated, easy to administer, and easily available over the counter [1, 2]. FA is a steroid antibiotic that was introduced for clinical use in the 1960s and has been used clinically for the systemic and topical treatment of staphylococcal infections [1, 2]. FA kills bacteria by inhibiting protein synthesis by binding to the ribosomal translocase elongation factor G (EF-G) [4]. Since EF-G is involved in the translocation part of translation, it forms a complex with guanosine triphosphatase catalyzing the movement of tRNA and mRNA through the ribosome. FA binds to EF-G and blocks the elongation of the polypeptide chain and EF-G-guanosine dinucleotide ribosomal complex release [4, 5].

Resistance to FA appeared following the extensive and widespread use of the antibiotic and has been reported in clinical isolates of S. aureus obtained in different countries [6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11]. Three common genetic determinants (fusA [mutation in fusA], fusB, and fusC) mediate FA resistance in S. aureus. These determinants vary in their genetic locations. fusA confers chromosomal resistance [5, 11, 12], while fusB and fusC are cytoplasmic and are located on plasmids or transposon-like elements [5, 6, 12, 13, 14, 15] although chromosomal fusB was also reported in the European FA-resistant S. aureus impetigo clone [7, 8].

The prevalence of resistance to FA in S. aureus varies in different countries [8, 9, 10, 11, 13]. In Kuwait, the prevalence of FA resistance has remained consistently high among clinical MRSA isolates [16, 17, 18]. A study of antibiotic resistance in S. aureus obtained in 21 laboratories located in 19 countries conducted in 1996 discovered that the prevalence of FA resistance in S. aureus obtained in Kuwait was 20% which was higher than the global average of 5% at the time [19]. Since then, the prevalence of FA resistance has continued to increase among MRSA isolates in Kuwait [10, 17, 18] and in other countries [8, 9, 11, 13] making FA resistance a major resistance problem in MRSA isolated globally.

The recent increase in FA resistance in S. aureus in many countries has been attributed to the emergence of novel genetic elements comprising fusC inserted into the staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) region of MRSA strains. The SCCmec region harbors the methicillin resistance gene (mecA), and the integration of fusC into the SCCmec region is suggested to enhance its rapid spread in MRSA belonging to different genetic backgrounds [11, 13, 15, 18].

Although FA resistance in MRSA obtained in Kuwait hospitals has been well documented [10, 16, 17, 18], data on the genetic determinants of FA resistance in Kuwait MRSA isolates are limited [18]. Understanding the mechanisms of FA resistance will be helpful for effective and appropriate use of the antibiotic. The aim of this study was to investigate the genetic determinants of FA resistance in MRSA strains collected from patients in Kuwait hospitals.

Materials and Methods

MRSA Isolates

The MRSA isolates were obtained as part of routine diagnostic microbiology investigations in 12 public hospitals using standard bacteriological protocols. The isolates were later submitted to the MRSA Reference Laboratory situated at the Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine, Kuwait University, Kuwait, for molecular typing. Prior antibiotic susceptibility testing of 1044 MRSA isolates obtained between January 1 and June 30, 2018, revealed that 97 (9.2%) isolates were resistant to FA. The FA-resistant isolates were preserved in 15% glycerol (v/v in brain heart infusion broth (Oxoid, Basingstoke, Leicester, UK) at −80°C and were investigated further in this study. The isolates were recovered by growth in brain heart infusion broth at 35°C for 24 h followed by 2 further subcultures on brain heart infusion agar [18].

Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

Antibiotic susceptibilities of the FA-resistant isolates were confirmed by the disk diffusion method on Mueller-Hinton Agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) and incubated for 24 h at 35°C. The following antibiotic discs were tested: cefoxitin (30 µg), penicillin (10 U), trimethoprim (5 µg), tetracycline (30 µg), kanamycin (30 µg), gentamicin (10 µg), erythromycin (15 µg), FA (10 µg), chloramphenicol (30 µg), rifampicin (5 µg), linezolid (30 µg), and mupirocin (200 µg). Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for cefoxitin, mupirocin, vancomycin, teicoplanin, and FA was determined with E-test strips (AB BioMerieux, Marcy l' Etoile, France) according to the manufacturer's instructions and interpreted according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial susceptibility testing [20]. S. aureus strains ATCC 25923 and ATCC 29213 were used as quality control strains for disk diffusion and MIC determinations, respectively. Methicillin resistance was confirmed by detecting PBP2A in culture supernatants of isolates using a rapid latex agglutination kit (Denka-Seiken, Tokyo, Japan) following the manufacturer's instructions [17].

Molecular Typing of MRSA Isolates

Isolation of bacterial DNA for amplification studies was performed as described previously [18]. Three to 5 identical colonies of an overnight culture were picked using a sterile loop and suspended in a microfuge tube containing 50 µL of lysostaphin (150 µg/mL) and 10 µL of RNase (10 µg/mL) solution. The tube was incubated at 37°C in the heating block (ThermoMixer, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) for 20 min. To each sample, 50 µL of proteinase K (20 mg/mL) and 150 µL of Tris buffer (0.1 M) were added and mixed by pipetting. The tube was then incubated at 60°C in the water bath (VWR Scientific Co., Shellware Lab, Radnor, PA, USA) for 10 min. The tube was transferred to a heating block at 95°C for 10 min to inactivate proteinase K activity. Finally, the tube was centrifuged, and the extracted DNA was stored at 4°C till used for PCR.

Spa Typing

Spa typing was performed as described previously by Harmsen et al. [21]. The PCR protocol consisted of an initial denaturation at 94°C for 4 min, followed by 25 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 56°C for 1 min, and extension for 3 min at 72°C, and a final cycle with a single extension for 5 min at 72°C. Five microliters of the PCR product was analyzed by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis to confirm amplification. The amplified PCR product was purified using the MicroElute Cycle-Pure Spin kit (Omega Bio-tek, Inc., Norcross, GA, USA), and the purified DNA was then used for sequencing PCR. The sequencing PCR product was then purified using the Ultra-Sep Dye Terminator Removal kit (Omega Bio-tek, Inc., Norcross, GA, USA). The purified DNA was sequenced in an automated 3130X1 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystem, Waltham, MA, USA). The sequenced spa gene was analyzed using Ridom Staph Type software available on Ridom SpaServer at https//spaserver.ridom.de.

DNA Microarray

All 97 FA-resistant isolates were investigated by DNA microarray using the S. aureus genotyping kit (Alere, Technology, Jena, Germany) for the molecular typing of S. aureus isolates. The method allows for the detection of genes for antibiotic resistance and virulence factors and the assignment of the isolates to clonal complexes (CCs). SCCmec types of the isolates were derived from DNA microarray analysis. The procedures were performed according to the protocol published previously [18, 22].

Amplification of FA Resistance Genes

The presence of fusA (mutation in fusA), fusB, and fusC was investigated by PCR using primers and methods published previously [5, 23]. fusA mutation was amplified with primers FusA-F (5′-CTC GTA AYA TCG GTA TCA TG-3′) and FusA-R (5′-GCA TAG TGA TCG AAG TAC-3′), fusC was amplified with primers FusC-F (5′-TTA AAG AAA AAG ATA TTG ATA TCT CGG-3′) and FusC-R (5′-TTT ACA GAA TCC TTT TAC TTT ATT TGG-3′), and for fusB, the primers Far1A (5′-ACT TGT CCG TGT GCT AAC-3′) and Far1B (5′-AGT TCG GGA GGT GAT GATG-3′) were used. The cycling conditions consisted of an initial denaturation step (94°C for 3 min), followed by 25 cycles of 94°C (30 s), 57°C (30 s), and 72°C (45 s) [5]. The PCR products were subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis in 1.5% (w/v) agarose gels containing ethidium bromide (0.5 mg/L) and visualized under ultraviolet light. The expected amplicon sizes in base pairs were fusA, 2,002 bp; fusB, 949 bp; and fusC, 332 bp [23]. Detection of mutations in fusA was performed by the rapid PCR amplification method for the detection of the L461K mutation in fusA as described previously by Castanheira et al. [23]. The amplification was performed using 4 primer sets [23]. PCR was performed in 20 µL using Master Mix (5X HOT FIRE Pol Blend, with 7.5 mM MgCl2; Solis Biodyne, Tartu, Estonia), 0.1–0.4 µM of primers, and 2 µL of the template. Cycling conditions were cell denaturation of 15 min at 95°C, followed by 35 cycles of 15 s at 94°C, 30 s at 50°C, and 45 s at 72°C for denaturing, annealing, and extension, respectively, and final extension at 72°C for 5 min. PCR products were visualized after 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. Two bands were detected in strains positive for L461K with 1 band of 415 bp and another with 145 bp. L461K-negative strains had 2 bands of 415 bp and 308 bp [23].

Results

The 97 FA-resistant MRSA isolates were obtained from wound swabs (n = 23), blood (n = 17), nasal swabs (n = 12), endotracheal aspirate (n = 6), urine (n = 5), groin (n = 5), axilla (n = 4), high vaginal swab (n = 3), umbilical cord swab (n = 3), throat swab (n = 3), ear swab (n = 3), eye swab (2), skin (n = 2), tissue (n = 2), sputum (n = 2), exit site (n = 1), fluid (n = 1), and unspecified sources (n = 2).

Antibiotic Resistance of FA-Resistant MRSA Isolates

The distribution of FA MIC levels is summarized in Table 1. The FA MICs ranged from 2 mg/L to >256 mg/L. Most of the isolates expressed low FA MICs (MIC 2–16 mg/L). Fourteen isolates expressed high FA MIC levels (MIC >256 mg/L). In addition to FA resistance, the MRSA isolates were resistant to the nonbeta-lactam antibiotics shown in Table 2. Most of the isolates were resistant to trimethoprim (n = 47) and tetracycline (n = 43). Of the 27 clindamycin-resistant isolates, 20 expressed inducible resistance, while 7 expressed constitutive resistance. Twenty-five isolates were resistant to chloramphenicol. All isolates were susceptible to vancomycin (MIC ≤2 mg/L), teicoplanin (MIC ≤2 mg/L), linezolid, rifampicin, and mupirocin.

Table 1.

Distribution of FA resistance determinants in MRSA isolates

| MIC, mg/L | FA resistance determinants |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fusA | fusB | fusC | total | ||

| 1 | 2 | − | − | 1 | |

| 2 | 4 | − | 4 | 76 | 80 |

| 3 | 12 | − | − | 1 | 1 |

| 4 | 16 | − | − | 1 | 1 |

| 5 | ≥256 | 14 | − | − | 14 |

|

| |||||

| Total | 14 | 4 | 79 | 97 | |

MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; FA, fusidic acid; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration.

Table 2.

Prevalence of antibiotic resistance in FA-resistant MRSA isolates

| Antibiotics | MRSA (%) |

|---|---|

| Trimethoprim | 47 (48.9) |

| Tetracycline | 43 (44.8) |

| Kanamycin | 32 (33.3) |

| Gentamicin | 28 (29.1) |

| Erythromycin | 27 (28.1) |

| Clindamycin | 27 (28.1) |

| Chloramphenicol | 25 (25.7) |

MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; FA, fusidic acid.

Prevalence of FA Resistance Determinants

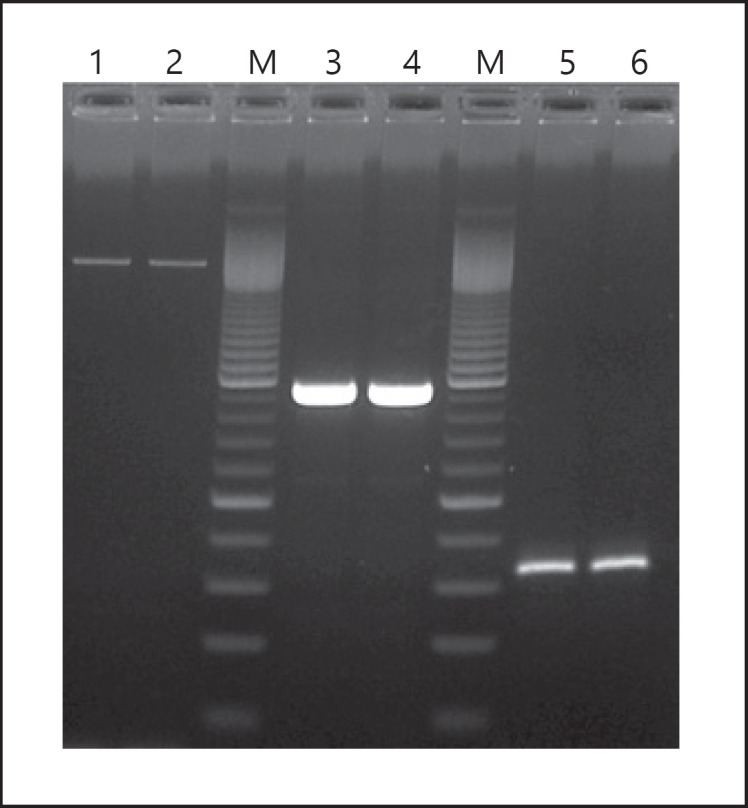

The distribution of the FA resistance determinants is summarized in Table 1. Figure 1 shows representative amplified products of the FA resistance determinants. The FA resistance determinants, fusA (fusA mutation), fusB, and fusC, were investigated by PCR amplification. In addition, results for fusB and fusC were extracted from DNA microarray analysis of the isolates as the DNA Microarray platform used in this study also contains probes for fusB and fusC. There was complete agreement in the results obtained by PCR and DNA microarray analysis for fusC and fusB. Table 1 contains the results obtained by both methods. Most of the isolates (n = 79; 81.4%) were positive for fusC, 14 isolates harbored fusA, and 4 isolates (4.1%) harbored fusB. One isolate was positive for both fusA and fusC. The association of the FA resistance determinants with FA MIC revealed that fusA was associated with high MIC values (MIC >256 mg/L) while fusB and fusC were associated with lower FA MIC values.

Fig. 1.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of amplified FA resistance determinants. Lanes 1 and 2 fusA (size 2,002 bp); lane M, molecular size marker − 100 bp ladders; lanes 3 and 4 fusB (size 949 bp); lanes 5 and 6 fusC (size 332 bp). FA, fusidic acid.

Detection of fusA Mutations

All 97 FA-resistant isolates were investigated for fusA mutations. The result is presented in Figure 2. The L461K mutation was detected only in the 14 isolates with high-level FA resistance (MIC >256 mg/L).

Fig. 2.

Agarose gel electrophoresis showing the L416K mutation. Lanes 1–3 fusA mutation (L416K); lane M molecular size marker (100 bp); lanes 4 and 5 no L416K mutation.

Genetic Backgrounds of FA-Resistant MRSA Isolates

The genetic backgrounds of the 97 FA-resistant isolates are presented in Table 3. The isolates were classified into 5 SCCmec types: SCCmec III, SCCmec IV, SCCmec V, SCCmec VI, and SCCmec V/VT; 23 spa types; 12 CCs; and 26 genotypes.

Table 3.

Genetic determinants of FA resistance in MRSA isolates

| Clonal complex | Strain description | Spa types | FA resistance determinants |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fusA | fusB | fusC | total | |||

| CC1 | CC1-MRSA-V + SCCfus [PVL+] | t127 | 5 | 5 | ||

| CC1-MRSA-IV + SCCfus | t127 | 1 | 1 | |||

|

| ||||||

| CC5 | CC5-MRSA-VI + SCCfus | t688 | 1 | 24 | 25 | |

| CC5-MRSA-V + SCCfus | t3235 | 1 | 1 | |||

| CC5-MRSA-VI + SCCfus | t2235 | 2 | 2 | |||

| CC5-MRSA-V + SCCfus | t311 | 13 | 13 | |||

| CC5-MRSA-V-[sed/j] | t954 | 1 | 1 | |||

| CC5-MRSA-V + SCCfus | t442 | 1 | 1 | |||

| CC5-MRSA-VI + SCCfus | t535 | 3 | 3 | |||

|

| ||||||

| CC8 | ST239-MRSA-III + SCCmer | t860 | 8 | 8 | ||

| ST239-MRSA-III + SCCmer | t945 | 2 | 2 | |||

| CC8-MRSA-IV [PVL+] | t008 | 1 | 1 | |||

|

| ||||||

| CC15 | CC15-MRSA-V + SCCfus | t084 | 4 | 4 | ||

|

| ||||||

| CC22 | CC22-MRSA-IV [fnbB; sec/I | t311 | 1 | 1 | ||

| C22-MRSA-IV [tst1] | t1612 | 1 | 1 | |||

|

| ||||||

| CC30 | CC30-MRSA-VI + fus[PVL+] | t018 | 2 | 2 | ||

|

| ||||||

| CC45 | CC45-MRSA-VI + fus | t362 | 4 | 4 | ||

|

| ||||||

| CC80 | CC80-MRSA-IV [PVL+] | t044 | 4 | 4 | ||

|

| ||||||

| CC88 | CC88-MRSA-IV | t690 | 1 | 1 | ||

| CC88-MRSA-IV[etA+] | t786 | 2 | 2 | |||

|

| ||||||

| CC97 | CC97-MRSA-V[fusC] | t2297 | 2 | 2 | ||

| CC97-MRSA-V[fusC] | t359 | 2 | 2 | |||

| CC97-MRSA-V[fusC] | t267 | 3 | 3 | |||

| CC97-MRSA-V[fusC] | nd | 4 | 4 | |||

|

| ||||||

| CC152 | CC152-MRSA-[V/VT+ PVL+) | t353 | 1 | 1 | ||

|

| ||||||

| CC361 | CC361-MRSA-V/VT+ fus | t3841 | 3 | 3 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Total | 14 | 4 | 79 | 97 | ||

MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; FA, fusidic acid; nd, not determined.

The dominant spa types were t688 (n = 25), t311 (n = 14), t860 (n = 8), and t127 (n = 6) which constituted 54.6% of the spa types. Spa types, t084, t362, and t044 were detected in 4 isolates each while t3841, t535, and t267 were each detected in 3 isolates. The remaining spa types were detected in 2 or single isolates. The spa types of 4 isolates were not determined.

Most of the isolates belonged to SCCmec V (n = 36) or SCCmec VI (n = 36) while 11 and 10 isolates belonged to SCCmec IV and SCCmec III, respectively. CC5 was the dominant CC. It comprised 44 isolates grouped into 7 genotypes. The other major CCs were CC8 (ST239) (11.3%), CC97 (11.3%), CC1 (6.1%), CC15 (5.1%), CC45 (4.1%), CC80 (4.1%), and CC88 (4.1%). The remaining CCs were less common (Table 3).

The common genotypes were CC5-MRSA-VI + SCCfus-t688 (n = 25), CC5-MRSA-V + SCCfus-t311 (n = 13), ST239-MRSA-III-t860 (n = 8), CC1-MRSA-V + SCCfus [PVL+] (n = 5), CC15-MRSA-V + SCCfus (n = 4), CC45-MRSA-VI + fus (n = 4), and CC80-MRSA-IV [PVL+] (n = 4). The other genotypes were detected in 1–3 isolates.

The distribution of the FA resistance determinants by genotypes showed that fusC was the most widely distributed FA resistance determinant. fusC was detected in all CCs except CC8 (ST239), CC80, and CC88. fusB was only detected in CC80 isolates while fusA mutation was found in CC5 (N = 1), CC22 (N = 1), CC88 (N = 2), and CC8 (ST239) (N = 10).

Discussion

This study investigated the genetic mechanisms of FA resistance in clinical MRSA isolates obtained in Kuwait hospitals. The results revealed the presence of the 3 common FA resistance determinants, fusA (fusA mutation), fusB, and fusC, that have been associated with FA resistance in S. aureus [5, 6, 7, 8, 9]. The study showed that fusC, detected in 81.4% of the isolates, was the dominant FA resistance determinant. This observation is consistent with results from other studies where fusC was more prevalent among FA-resistant MRSA isolates in Taiwan [15] and in MRSA obtained from patients with atopic dermatitis in Denmark [24].

The fusA mutation, detected in 14.4% of the isolates, was the second common FA resistance determinant in this study. The isolates with mutations in fusA expressed high-level FA resistance (MIC >256 mg/L) and harbored the L416K mutation. Although different mutations have been associated with fusA, the L461K mutation is more common in S. aureus [23, 25]. Therefore, the high-level FA-resistant isolates were investigated for the presence of the L416K mutations, and all 14 high-level FA-resistant isolates carried the L416K mutation. The association of high-level FA resistance with fusA mutations observed in this study is consistent with previous studies from Europe [5, 24] and Taiwan [25] that had associated fusA with high-level FA resistance (MIC ≥64 mg/L) and fusB or fusC with low-level resistance (MIC <32 mg/L).

The fusB determinant was detected in the least number (4.1%) of isolates in this study. In contrast, fusB was the most prevalent FA resistance determinant in MRSA isolated in Jordan [26], Wenzhou, China [27], and in some European countries due to an epidemic strain associated with outbreaks of impetigo bullosa infections and clonal expansion of the European CA-MRSA clone belonging to ST80 [7, 8, 13, 24]. These reports highlight differences in the geographical distribution of FA resistance determinants in MRSA isolates.

One isolate with high-level FA resistance harbored both fusA and fusC determinants suggesting that the high MIC expressed by fusA was probably masking the lower MIC associated with fusC. The simultaneous carriage of double FA resistance determinants in individual strains is rare. Previous reports include the simultaneous carriage of fusB + fusC in one of 25 MRSA isolates and in 2 of 34 FA-resistant MRSA in separate Taiwanese hospitals [28], the presence of fusB + fusC in one of 26 FA-resistant MRSA in Egypt [29], and the presence of fusB + fusA (2 isolates) and fusC + fusA (1 isolate) in MRSA isolates in Denmark [7]. The simultaneous carriage of fusA + fusC in this study adds to the growing list of this phenomenon. Similar to the observation in this study, in vitro studies by O'Neill and Chopra [6] revealed that when a plasmid-mediated fusB was introduced into a strain carrying chromosomally mutated fusA, it retained the MIC values of the determinant exhibiting the highest MIC values (fusA). A similar observation was reported in clinical MRSA isolates carrying fusC + fusA or fusB + fusA where the FA MIC corresponded to the MIC expressed by fusA [5]. Furthermore, a report of a study from Egypt revealed that when an FA-resistant MRSA which carried both fusB and fusC and expressed high-level resistance (MIC 1,024 mg/L) was cured of the plasmid-mediated fusB, the loss of the plasmid resulted in the reduction of FA MIC values by 16–64-folds suggesting that the FA resistance in this isolate was additive [29]. These results highlight the complexities of FA resistance determinants in MRSA isolates [5, 6].

This study revealed that the FA-resistant MRSA isolates belonged to diverse genetic backgrounds consisting of 23 spa types, 12 CCs, and 16 genotypes with CC5 (48.4%) as the dominant CC followed by CC97 (11.3%) and CC8 (11.3%). The dominant genotypes were CC5-MRSA-VI + SCCfus-t688 (25.7%), CC5-MRSA-V + SCCfus-t311 (13.4%), and CC8 (ST239-MRSA-III-t860) (8.2%). Furthermore, while fusC was widely distributed among the different genetic backgrounds, fusB was limited to CC80, and fusA that was associated with high-level FA resistance (MIC >256 mg/L) was restricted to ST239-MRSA-III, CC5, CC22, and CC88 isolates. Prior to this study, Boswihi et al. [18] reported the presence of fusC in 87.2% of novel variants of MRSA that belonged to diverse genetic backgrounds in Kuwait. Hence, the current detection of fusC in 10 of the 12 CCs confirms an ongoing expansion of fusC among FA-resistant MRSA in Kuwait hospitals. Similarly, Ellington et al. [13] found fusC in CA-MRSA belonging to different genetic backgrounds including ST1, ST5, ST8, ST45, and ST149, while FA-resistant MRSA carrying fusC in Malaysia belonged to multiple genetic backgrounds [15], and FA-resistant MRSA obtained from children in Greece belonged to ST80, ST30, and ST22 [30]. These results highlight the growing contribution of fusC to the increasing prevalence of FA resistance in S. aureus.

Conclusion

The study has revealed a high prevalence of fusC in FA-resistant MRSA belonging to diverse genetic backgrounds. This study has increased our understanding of the genetic determinants of FA resistance in MRSA isolated in Kuwait hospitals. The increasing prevalence of FA resistance and the evolution of the combination of fusC with SCCmec genetic elements observed in this and other studies warrant a review of topical FA use in the country so as not to completely lose its efficacy against S. aureus.

Statement of Ethics

The strains used in this study were obtained as part of routine diagnostic services. Therefore, no ethical approval was required.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Funding Sources

There was no external funding for this study.

Author Contributions

E.E.U. and W.A. initiated the study. H.A.B., F.A.M., and T.V. performed the experiments. All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting, and revising the manuscript and approved the final version for publication.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are available within the text.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the staff of the MRSA Reference Laboratory for technical support.

References

- 1.Pangilinan R, Tice A, Tillotson G. Topical antibiotic treatment for uncomplicated skin and skin structure infections: review of the literature. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2009;7:957–65. doi: 10.1586/eri.09.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williamson DA, Carter GP, Howden BP. Current and emerging topical antibacterial and antiseptic: agents, action, and resistance patterns. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017;30:827–60. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00112-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gajdács M, Ábrók M, Lázár A, Burián K. Increasing relevance of gram-positive cocci in urinary tract infections: a 10-year analysis of their prevalence and resistance trends. Sci Rep. 2020 Oct 19;10((1)):17658. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-74834-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodley JW, Zieve FJ, Lin L, Zieve ST. Formation of the ribosome-G factor-GDP complex in the presence of fusidic acid. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1969;37:437–43. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(69)90934-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McLaws FB, Larsen AR, Skov RL, Chopra I, O'Neill AJ. Distribution of fusidic acid resistance determinants in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:1173–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00817-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Neill AJ, Chopra I. Molecular basis of fusB-mediated resistance to fusidic acid in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol. 2006;59:664–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Neill AJ, Larsen, Henriksen AS, Chopra I. A fusidic acid: resistant epidemic strain of Staphylococcus aureus carries fusB determinant, whereas fusA mutations are prevalent in other resistant isolates. Antimcrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:3594–7. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.9.3594-3597.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rijnders MI, Wolffs PF, Hopstaken RM, den Heyer M, Bruggeman CA, Stobberingh EE. Spread of the epidemic European fusidic acid-resistant impetigo clone (EEFIC) in general practice patients in the south of The Netherlands. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:1176–80. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williamson DA, Monecke S, Heffernan H, Ritchie SR, Roberts SA, Upton A, et al. High usage of topical fusidic acid and rapid clonal expansion of fusidic acid-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a cautionary tale. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:1451–4. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Udo EE, Boswihi SS. Antibiotic resistance trends in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated in Kuwait hospitals: 2011–2015. Med Princ Pract. 2017;26:485–90. doi: 10.1159/000481944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baines SL, Howden BP, Heffernan H, Stinear TP, Carter GP, Seemann T, et al. Rapid emergence and evolution of staphylococcus aureus clones harboring fusC-containing staphylococcal cassette chromosome elements. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60:2359–65. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03020-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gajdacs M. The continuing threat of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antibiotics. 2019;8:52. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics8020052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellington MJ, Reuter S, Harris SR, Holden MT, Cartwright EJ, Greaves D, et al. Emergent and evolving antimicrobial resistance cassettes in community-associated fusidic acid and meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2018;45:477–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim KT, Teh CS, Yusof MY, Thong KL. Mutations in rpoB and fusA cause resistance to rifampicin and fusidic acid in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains from a tertiary hospital in Malaysia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2014;108:112–8. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trt111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin YT, Tsai JC, Chen HJ, Hung WC, Hsueh PR, Teng LJ. A novel staphylococcal cassette chromosomal element, SCCfusC, carrying fusC and speG in fusidic acid-resistant methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:1224–7. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01772-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Udo EE, Jacob LE. Characteristics of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from Kuwait hospitals with high-level fusidic acid resistance. J Med. Microbiol. 2000;49:419–26. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-49-5-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Udo EE, Al-Sweih N, Dhar R, Dimitrov TS, Mokaddas EM, Johny M, et al. Surveillance of antibacterial resistance in Staphylococcus aureus isolated in Kuwaiti hospitals. Med Princ Pract. 2008;17:71–5. doi: 10.1159/000109594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boswihi SS, Udo EE, Monecke S, Mathew B, Noronha B, Verghese T, et al. Emerging variants of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus genotypes in Kuwait hospitals. PLoS One. 2018;13((4)):e0195933. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zinn CS, Westh H, Rosdahl VT, The SARISA Study Group An international multicenter study of antimicrobial resistance and typing of hospital Staphylococcus aureus isolates from 21 laboratories in 19 countries or states. Microb Drug Resist. 2004;10:160–8. doi: 10.1089/1076629041310055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.European Committee on Antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MIC and zone diameters. Version 10.0 Valid from. 2020. Jan 1.

- 21.Harmsen D, Claus H, Witte W, Rothgänger J, Claus H, Turnwald D, et al. Typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a university hospital setting by using novel software for spa repeat determination and database management. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:5442–8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.12.5442-5448.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monecke S, Jatzwauk L, Weber S, Slickers P, Ehricht R. DNA microarray-based genotyping of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains from Eastern Saxony. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14:534–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.01986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castanheira M, Watters AA, Mendes RE, Farrell DJ, Jones RN. Occurrence and molecular characterization of fusidic acid resistance mechanisms among Staphylococcus spp. from European countries (2008) J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:1353–8. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edslev SM, Clausen ML, Agner T, Stegger M, Andersen PS. Genomic analysis reveals different mechanisms of fusidic acid resistance in Staphylococcus aureus from Danish atopic dermatitis patients. J Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:1173–6. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen HJ, Hung WC, Tseng SP, Tsai JC, Hsueh PR, Teng LJ. Fusidic acid resistance determinants in Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates. Antimicrob agents Chemother. 2010;54:4985. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00523-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aldasouqi R, Abu-Qatouseh LF, Badran EF, Alhaj Mahmoud SA, Darwish RM. Genetic determinants of resistance to fusidic acid among Staphylococcus aureus isolates in Jordan. Jundishapur J Microbiol. 2019;12((3)):e86120. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu F, Liu Y, Lu C, Lv J, Qi X, Ding Y, et al. Dissemination of fusidic acid resistance among Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates. BMC Microbiol. 2015;15:210. doi: 10.1186/s12866-015-0552-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen CM, Huang M, Chen HF, Ke SC, Li CR, Wang JH, et al. Fusidic acid resistance among clinical isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a Taiwanese hospital. BMC Microbiol. 2011 May 12;11:98. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abouelfetouh A, Kassem M, Naguib M, El-Nakeeb M. Investigation and treatment of fusidic acid resistance among methicillin-resistant staphylococcal isolates from Egypt. Microb Drug Resist. 2017;23:8–17. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2015.0336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katopodis GD, Grivea IN, Tsantsaridou AJ, Pournaras S, Petinaki E, Syrogiannopoulos GA. Fusidic acid and clindamycin resistance in community-associated, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in children of central Greece. BMC Infect Dis. 2010 Dec 13;10:351. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are available within the text.