Abstract

Background

Assessing the public’s willingness to pay (WTP) for the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine by the contingent valuation (CV) method can provide a relevant basis for government pricing. However, the scope issue of the CV method can seriously affect the validity and reliability of the estimation results.

Aim

To examine whether there are scope issues in respondents’ WTP for the COVID-19 vaccine and to further verify the validity and reliability of the CV estimate results.

Method

In this study, nine different CV double-bounded dichotomous choices (DBDC) hypothetical COVID-19 vaccine scenarios were designed using an orthogonal experimental design based on the vaccine’s attributes. A total of 2450 samples from 31 provinces in Mainland China were collected to independently estimate the public’s WTP in these nine scenarios with logistic, normal, log-logistic and log-normal parameter models. Based on this estimation, several external scope tests were designed to verify the validity and reliability of the CV estimate results.

Results

In the 20 pairs of COVID-19 vaccine scenarios, 6 pairs of scenarios were classified as negative scope issues, therefore not passing the external scope test. Of the remaining 14 pairs of scenarios, only four pairs of scenarios completely passed the external scope test, and one pair of scenarios partially passed the external scope test. Significant negative scope and scope insensitivity issues were revealed.

Conclusion

In the context of a dynamic pandemic environment, the findings of this study reveal that the CV method may face difficulty in effectively estimating respondents’ WTP for the COVID-19 vaccine. We suggest that future studies be cautious in applying the CV method to estimate the public’s WTP for the COVID-19 vaccine.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40258-021-00706-9.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| We found negative scope and scope insensitivity issues in the evaluation of the willingness to pay (WTP) for the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine by using the contingent valuation (CV) method, which could seriously affect the validity and reliability of the estimation results. |

| In the context of a dynamic pandemic environment, the CV method should be used cautiously to estimate the public’s WTP for the COVID-19 vaccine. |

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has spread rapidly throughout the world since the end of 2019. This crisis has posed a great threat to the health and life of worldwide populations and has had a dramatic impact on society and economics [1]. As of 5 June 2021, there were 172.24 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 with 370.94 thousand deaths worldwide [2]. Compared to that in other countries, the spread of COVID-19 in China has been more effectively controlled, with 403 confirmed cases remaining in Mainland China as of 6 June 2021 [3]. The COVID-19 vaccine is an effective tool in the fight against this virus [4] and can significantly decrease COVID-19 infection. In China, the public is offered the COVID-19 vaccine free of charge. The vaccine and labour costs are jointly borne by the medical insurance fund and the state finance. The government and enterprises negotiated to determine the price of the vaccine [5]. Therefore, on the one hand, estimating the willingness to pay (WTP) for the COVID-19 vaccine can provide a relevant basis for government pricing. On the other hand, this study examines the validity and reliability of the contingent valuation (CV) method, which can be used for pricing.

The CV method is a typical stated preference technique used to estimate WTP and has been widely used for various vaccines, e.g., dengue vaccines [6–8], pneumococcal vaccines [9, 10], cholera vaccines [11–13] and others. There are currently several studies that use the CV method to estimate the WTP for the COVID-19 vaccine across different countries, such as Chile [14, 15], Indonesia [16], Ecuador [17], Vietnam [18] and China [19]. These studies have provided some significant information in terms of understanding the public’s preference for the COVID-19 vaccine; however, the issue of scope was ignored by these studies when using the CV method. This long-standing bias problem [20] greatly limits the validity and reliability of the CV method [21, 22].

The issue of scope refers to respondents’ WTP varying very little with the quantity or quality of goods or the area of environmental goods, which violates economic rationality [23]. One classic issue regarding scope was first defined by Mitchell and Carson as part-whole bias [24]. Since the Exxon Valdez oil spill incident in 1989, studies on the validity and reliability of the CV method have gradually increased, and the issue of scope has also been widely considered amongst them [25, 26]. A typical issue of scope case is the work of Desvousges et al, in which they estimated the public’s WTP for protecting wildfowl [27]. They found that there was little difference in the WTP for protecting 2000, 20,000 or 200,000 wild birds. In terms of health care, there are also some studies on the issue of scope. The scope of change usually includes the reduction of disease risk and the severity of disease [28]. Hausman, a critic of CV, reviewed some studies that failed to pass the scope test and the related issues of CV and considered this method to be “hopeless” [20]. In contrast, Carson stated that although the CV method is not perfect, there is no better alternative in valuing goods [25].

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) expert panel has suggested that an external scope test should be conducted to verify whether the responses to the scope of estimated goods are adequate to demonstrate the validity and reliability of the CV method [29]. Scope tests include the internal scope and external scope tests [30]. The internal scope test, as a paired sample test, compares the values of the same respondents on different levels of scenarios, and is called the weak test; the external scope test, also known as the split sample test, compares the values of different respondents on different levels of scenarios, and is described as the strong test [31]. The internal scope test controls the between-subject variation and has more power but has not been able to convince CV critics [32]. Meanwhile, the external scope test is overlooked due to its high requirements [26]. However, some scholars have suggested that an external scope test is necessary to study the reliability of the CV method [33].

However, compared with the wide application of scope tests in the environmental and ecological fields, only a few studies have used scope tests in the vaccine field [34–38], and most have regarded the scope test as only an auxiliary tool to prove validity, without specialised exploration. Among them, a study specially designed for the scope issue, failed to pass the scope test after controlling the externality and warm glow [38]. Therefore, more research and exploration of CV methods in this field is required.

COVID-19 is spreading around the world and mutating over time, affecting its severity, infectivity and stability [39]. The COVID-19 vaccine is still undergoing clinical trials, so the specific conditions of its effectiveness, duration of protection and side effects are not sufficiently clear. Based on this situation, the CV method, which presents a single vaccine scenario to respondents, may therefore produce results with weak validity and reliability. To verify the existence of this problem, we generated 9 hypothetical COVID-19 vaccine scenarios with three attributes that may affect respondents’ WTP for the vaccine using an orthogonal experimental design. To conduct the external scope test, this study estimated respondents’ WTP across each scenario, i.e., each respondent valued only one vaccine scenario. Based on the results, we designed multiple external scope tests to verify the validity and reliability of the results in the context of a continuous pandemic environment.

Taking the Chinese COVID-19 vaccine as a case, the objective of this study is to evaluate the feasibility of using the CV method to estimate the WTP of the vaccine, especially in the context of pandemic changes and vaccine uncertainty. The issue of scope is the most critical challenge among the three major bias problems of the CV method [20]. This study further complemented the research on the issue of scope in the vaccine field and investigated the negative scope and scope insensitivity issues in the CV method. A negative scope means that the respondents’ WTP for parts is higher than that of the entire good [40]. In this study, a negative scope implies that the respondents value a suboptimal vaccine higher than a better vaccine. Scope insensitivity signifies that the WTP for the better vaccine was similar to that of the suboptimal vaccine, which was not statistically significant.

Sample and Methods

Study Design

We conducted a 9-day online survey using the Wenjuanxing platform1 from 28 January to 5 February 2021 since the pandemic has made it difficult to carry out offline face-to-face investigations. Wenjuanxing, like SurveyMonkey, is a professional network survey platform in China. The target group of the survey in this study was adults aged 18 years and older in Mainland China, and the distribution of sample residences was controlled in line with the population distribution, covering all provinces in China. Using the snowball sampling method, the project leader contacted 217 people from 31 provinces in four regions of Mainland China (Online Appendix 2) and asked them to continue snowballing and sending questionnaires.

Previous studies have shown that the public’s WTP for vaccines is affected by individual risk perceptions, attitudes towards vaccinations, and individual socioeconomic characteristics [41, 42]. The questionnaire therefore consisted of three parts. The first part included the benefit perceptions (5 items) and obstacle perceptions (8 items) of vaccination. The second part was the CV question, in which respondents read a detailed description of the hypothetical COVID-19 vaccine scenario and answered whether they were willing to pay for the vaccine. If the answer was “yes”, then the WTP amount was finalised; otherwise, the respondents continued to the question on the reasons for such unwillingness to pay. The third part included sociodemographic characteristics, including age, gender, income, educational background, occupation, marital status, number of children, place of residence, urban or rural area, and chronic diseases.

In the questionnaire, the CV question included specific attributes of the COVID-19 vaccine and the corresponding levels (see Online Appendix 1 for the detailed scenario description). Based on previous studies of vaccine preferences [14, 16], we selected the following three key attributes that evidently affect public preferences for vaccines: effectiveness2, the duration of protection3, and side effects4. At present, COVID-19 vaccines are still in the clinical stage, so the levels of various attributes are not quite clear. We referred to the official websites of large Chinese pharmaceutical companies and relevant government departments and finally determined three levels of effectiveness (65%, 80% and 95%), three levels of duration of protection (1 year, 2 years and 3 years) and two levels of side effects (mild adverse reactions5 and no side effects). Nine hypothetical COVID-19 vaccines in the CV scenario were identified using an orthogonal experimental design, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Vaccine attributes and levels in nine contingent valuation (CV) scenarios

| Scenario | Effectiveness (%) | Duration of protection (unit: year) | Side effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 65 | 1 | Mild adverse reactions |

| S2 | 65 | 2 | Mild adverse reactions |

| S3 | 65 | 3 | No side effects |

| S4 | 80 | 1 | No side effects |

| S5 | 80 | 2 | Mild adverse reactions |

| S6 | 80 | 3 | Mild adverse reactions |

| S7 | 95 | 1 | Mild adverse reactions |

| S8 | 95 | 2 | No side effects |

| S9 | 95 | 3 | Mild adverse reactions |

The WTP-eliciting techniques include open-ended, payment card, bidding game and dichotomous choice. We employed the double-bounded dichotomous choice (DBDC) method, as recommended by the NOAA expert panel. After reviewing the CV scenario and providing a positive response to the question of whether he or she would be willing to pay for the vaccination, the respondent was asked if he or she would be willing to pay a randomly assigned initial bid value. If the respondent answered “yes”, then he or she was further asked whether he or she would be willing to pay a price higher than the initial bid value. Similarly, if the respondent answered “no”, then he or she was provided with a lower bid value.

After the questionnaire had been designed, two medical professors were consulted and a pilot survey from 24 January to 25 January 2021 was conducted. A payment card was used to determine the bid values of dichotomous choice techniques, and the finalised bid values are shown in Table 2. At the same time, we also tested the respondents’ understanding of various parts of the questionnaire, especially the descriptions of the attributes in the CV scenario. In the formal survey, we consider scenario randomisation6 and bid value randomisation7 through the Wenjuanxing platform. After opening the electronic questionnaire, the respondents were randomly assigned one of the nine COVID-19 vaccine scenarios and one of the six initial bid values (if the answer was “yes” when asked “are you willing to pay for the COVID-19 vaccine”). Therefore, independent estimations of nine vaccine scenarios and the approximate uniform distribution of bid values under each scenario were achieved.

Table 2.

Bid values in the double-bounded dichotomous choice (DBDC) technique (unit: ¥)

| Scheme | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bid value | 0 | 50 | 100 | 200 | 300 | 500 |

| Initial bid value | 50 | 100 | 200 | 300 | 500 | 1000 |

| Higher bid value | 100 | 200 | 300 | 500 | 1000 | 2000 |

Statistical Models

The DBDC question is based on the single-bounded dichotomous choice (SBDC) question, so we applied both the SBDC and DBDC techniques to calculate the mean WTP.

In the SBDC technique, the respondent answered “yes (y)” or “no (n)” to the initial bid value, C0, and the probability of the th respondent’s answer can be expressed, respectively, as follows:

| 1 |

| 2 |

in which is a cumulative distribution function with parameter . The parameter vector includes the coefficients of the bid value and other individual characteristics. The optimal solution of the parameter vector is obtained by the maximum likelihood estimate. Given sample size , the log-likelihood equation is as follows:

| 3 |

in which is a dummy variable and indicates the th respondent’s positive answer. Therefore, when the th respondent answered “yes”, and otherwise, ; is the opposite.

Similarly, in the DBDC technique, respondents had four possible answers to initial bid value C0, higher bid value Ch or lower bid value Cl: “yes–yes (yy)”, “yes–no (yn)”, “no–yes (ny)”, or “no–no (nn)”; the probability of the th respondent’s answer can be expressed as follows:

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

| 7 |

Thus, the log-likelihood equation is as follows:

| 8 |

in which is a dummy variable and indicates the th respondent’s yy answer. Thus, when the th respondent answered “yes–yes” to two questions; otherwise, ; the remaining dummy variables are denoted similarly.

The parameter estimation of the above model requires the assumption of the distribution function of WTP. In this paper, four distribution functions—logistic, normal, log-logistic and log-normal—are adopted to estimate the mean WTP. The logistic and normal distributions are symmetrical and may contain a negative WTP, while the log-logistic and log-normal distributions take the logarithm of the bid values, which eliminates the negative WTP, but the latter distributions are accompanied by fat tails. To date, there has been no consensus on the optimal distribution assumption; this work selected the optimal model through the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and log-likelihood [17].

According to Hanemann [43], the mean WTP of the SBDC and DBDC models can be calculated as follows:

| 9 |

in which is the maximum bid value, ¥2000. If is the logistic cumulative distribution function, then WTP can be calculated as follows:

| 10 |

where is the estimated coefficient of the bid value, is the estimated coefficient vector of individual characteristics, is the mean vector of individual characteristics, and α is a constant. The other parameter distributions can be calculated using the same method.

Scope Tests and Hypotheses

On the basis of economic theory, there will be a decline in demand when the prices of goods increase, and there will be a rise in expenses when the quality of goods improves. In the dichotomous choice technique, this concept reflects that the proportion of respondents who answered “yes” should decrease as the bid value increased, and when one vaccine was superior to another, the better one should provide higher utility, resulting in a higher WTP. When all attribute levels of one vaccine are equal to or better than the levels of another vaccine (at least one better), it indicates that the former is superior to the latter, and the WTP of the two vaccines can be tested for scope. We conducted several types of external scope tests, including negative scope issue tests and scope insensitivity issue tests. If the WTP for the suboptimal vaccine was higher than that for the optimal vaccine in four models with different parameter distributions, then we classified this situation as a negative scope issue, and therefore, no further testing for scope insensitivity was needed. In this study, a total of 20 pairs of COVID-19 vaccines in the paired combinations of 9 vaccine scenarios satisfied the above relationship, which can be used to test the hypotheses. The relationships and hypotheses are further clarified below.

Considering vaccine scenarios S1 (65% effectiveness, 1-year duration of protection with mild adverse reactions) and S2 (65% effectiveness, 2-year duration of protection with mild adverse reactions), S2 has a longer duration of protection than S1, while the other attribute levels are the same. Similarly, compared with S1, S3 (65% effectiveness, 3-year duration of protection with no side effects) is better in terms of duration of protection and side effects, and S8 (95% effectiveness, 2-year duration of protection with no side effects) is better in terms of effectiveness, duration of protection and side effects. We assume that the WTP values for S2, S3 and S8 should be higher than that of S1. According to the number of different attributes between the two vaccines that can be tested, the hypotheses were divided into 3 categories, i.e., I, II and III, representing that 1, 2, and 3 attributes had differences, respectively. For example, S2 had only 1 attribute that was different from S1, which was a better scenario; thus, the category I hypothesis assumed the following:

| 11 |

S3 had 2 attributes that were better than those of S1, and the third attribute was the same, so the category II hypothesis assumed the following:

| 12 |

S8 had 3 attributes that were all better than those of S1, so the category III hypothesis assumed the following:

| 13 |

All hypotheses are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Three categories of hypotheses

| Category I | Category II | Category III |

|---|---|---|

Results

Summary Statistics

During the survey, 2550 respondents completed the questionnaire, 100 of whom were excluded because they were not from Mainland China or provided protest responses. Of the 2450 total samples, 545 (22.2%) were not willing to pay for the vaccine. Regarding the reasons that respondents were unwilling to pay, 34% wanted to wait for someone else to get vaccinated first, and 25% questioned the safety of the vaccines. The remaining 1905 respondents were willing to pay for the vaccine and were included in further WTP calculations and scope tests.

The distribution of the sociodemographic characteristics of the pooled sample and subsamples is shown in Table 4. In the pooled sample, women accounted for 54.9%; respondents aged 18–40 years accounted for 77.9%, with an average age of approximately 33 years; the majority were undergraduates or above (82.8%); those with an average monthly income of more than ¥8000 (32.8%) accounted for the largest proportion; 6.4% of respondents engaged in medical-related work; 54.7% were married; 47.1% had at least one child; and the majority of respondents lived in cities (85.0%), had no chronic diseases (82.7%) and lived in East (47.8%) or West (26.7%) China. A comparison of the regional distribution of the samples and the total population is included in Online Appendix 2. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to test for differences in the characteristics among the nine independent subsamples. The results showed that all the characteristics passed the test, so there were no significant differences among the subsamples.

Table 4.

Characteristics of the pooled sample and subsamples

| Variables | Pooled sample (%) | Subsamples | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 (%) | S2 (%) | S3 (%) | S4 (%) | S5 (%) | S6 (%) | S7 (%) | S8 (%) | S9 (%) | Kruskal-Wallis test (p value) | ||

| Gender | |||||||||||

| Male = 1 | 45.1 | 43.7 | 46.0 | 49.2 | 44.7 | 44.8 | 44.9 | 47.3 | 42.5 | 42.5 | 0.837 |

| Female = 0 | 54.9 | 56.3 | 54.0 | 50.8 | 55.3 | 55.2 | 55.1 | 52.7 | 57.5 | 57.5 | |

| Age | |||||||||||

| 18–25 = 1 | 27.4 | 22.8 | 26.0 | 32.7 | 23.5 | 27.8 | 27.0 | 29.2 | 30.5 | 27.2 | 0.186 |

| 26–30 = 2 | 18.9 | 19.7 | 21.5 | 15.8 | 17.4 | 23.8 | 21.5 | 18.1 | 16.0 | 16.7 | |

| 31–40 = 3 | 31.6 | 30.7 | 32.1 | 33.1 | 35.8 | 23.1 | 35.5 | 30.3 | 33.1 | 31.0 | |

| ≥ 41 = 4 | 22.1 | 26.8 | 20.4 | 18.8 | 23.2 | 25.3 | 16.0 | 22.4 | 20.4 | 25.1 | |

| Education background | |||||||||||

| Junior college and below = 1 | 17.2 | 16.5 | 21.9 | 15.0 | 15.7 | 18.4 | 19.1 | 17.0 | 14.9 | 16.7 | 0.850 |

| Undergraduate = 2 | 48.7 | 45.3 | 43.0 | 51.1 | 50.2 | 47.3 | 48.8 | 52.0 | 49.8 | 49.8 | |

| Postgraduate and above = 3 | 34.1 | 38.2 | 35.1 | 33.8 | 34.1 | 34.3 | 32.0 | 31.0 | 35.3 | 33.4 | |

| Average monthly income in 2019 (¥) | |||||||||||

| ≤ 2000 = 1 | 22.3 | 20.1 | 22.6 | 25.9 | 18.1 | 25.6 | 25.0 | 19.5 | 24.7 | 19.9 | 0.094 |

| 2001–5000 = 2 | 20.7 | 17.7 | 29.4 | 18.4 | 19.1 | 19.9 | 22.7 | 24.5 | 15.6 | 19.5 | |

| 5001–8000 = 3 | 24.2 | 29.9 | 18.9 | 25.2 | 26.6 | 25.3 | 18.4 | 22.7 | 25.8 | 24.4 | |

| ≥ 8000 = 4 | 32.8 | 32.3 | 29.1 | 30.5 | 36.2 | 29.2 | 34.0 | 33.2 | 33.8 | 36.2 | |

| Engaged in medical related work | |||||||||||

| No = 0 | 93.6 | 94.5 | 93.2 | 93.2 | 94.5 | 91.7 | 94.5 | 94.2 | 95.3 | 91.6 | 0.617 |

| Yes = 1 | 6.4 | 5.5 | 6.8 | 6.8 | 5.5 | 8.3 | 5.5 | 5.8 | 4.7 | 8.4 | |

| Marriage | |||||||||||

| Unmarried = 0 | 45.3 | 42.5 | 50.6 | 46.2 | 39.2 | 50.5 | 44.5 | 45.1 | 44.4 | 44.9 | 0.179 |

| Married, divorced or widowed = 1 | 54.7 | 57.5 | 49.4 | 53.8 | 60.8 | 49.5 | 55.5 | 54.9 | 55.6 | 55.1 | |

| Children | |||||||||||

| No = 0 | 52.9 | 50.0 | 55.8 | 53.4 | 47.4 | 59.9 | 51.6 | 53.4 | 52.4 | 52.3 | 0.197 |

| Yes = 1 | 47.1 | 50.0 | 44.2 | 46.6 | 52.6 | 40.1 | 48.4 | 46.6 | 47.6 | 47.7 | |

| Locations | |||||||||||

| Rural = 0 | 15.0 | 10.6 | 18.1 | 16.5 | 14.3 | 15.5 | 14.8 | 13.4 | 15.3 | 16.0 | 0.502 |

| Urban = 1 | 85.0 | 89.4 | 81.9 | 83.5 | 85.7 | 84.5 | 85.2 | 86.6 | 84.7 | 84.0 | |

| Chronic disease | |||||||||||

| No = 0 | 82.7 | 79.9 | 84.2 | 82.3 | 82.6 | 82.3 | 82.0 | 83.0 | 86.2 | 81.2 | 0.790 |

| Yes = 1 | 17.3 | 20.1 | 15.8 | 17.7 | 17.4 | 17.7 | 18.0 | 17.0 | 13.8 | 18.8 | |

| Region | |||||||||||

| Eastern = 1 | 47.8 | 44.5 | 43.8 | 45.5 | 48.5 | 51.3 | 51.2 | 47.7 | 49.1 | 48.8 | 0.801 |

| Central = 2 | 14.1 | 15.4 | 15.8 | 16.2 | 14.0 | 11.9 | 14.1 | 14.1 | 13.5 | 12.2 | |

| Western = 3 | 26.7 | 26.8 | 30.6 | 25.2 | 26.6 | 24.9 | 24.2 | 27.8 | 28.0 | 25.8 | |

| Northeast = 4 | 11.4 | 13.4 | 9.8 | 13.2 | 10.9 | 11.9 | 10.5 | 10.5 | 9.5 | 13.2 | |

In the pooled sample, 77.7% of respondents were willing to pay for COVID-19 vaccines, of whom 80.9% and 76.3% answered “yes” to the first and second bids, respectively (Table 5). Table 6 shows the distribution of the bid values and payment rates of the subsamples. Of the 9 scenarios, S6 had the lowest payment rate (70.3%), and S8 had the highest payment rate (85.8%), with a difference of 15.5%.

Table 5.

Distribution of respondents’ responses in the pooled sample

| Bid | Response | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The first bid | Yes | No | ||

| Respondents (%) | 1541 (80.9%) | 364 (19.1%) | ||

| The second bid | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Respondents (%) | 1176 (76.3%) | 365 (23.6%) | 124 (34.1%) | 240 (65.9%) |

Table 6.

Distribution of sample in each bid value and the payment rate

| Scenario | Initial bid (unit: ¥) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | 100 | 200 | 300 | 500 | 1000 | Total | N | Payment rate (%) | |

| S1 | 25 (13.9%) | 39 (21.7%) | 23 (12.8%) | 35 (19.4%) | 27 (15.0%) | 31 (17.2%) | 180 | 254 | 70.8 |

| S2 | 36 (17.5%) | 34 (16.5%) | 25 (12.1%) | 38 (18.4%) | 35 (17.0%) | 38 (18.4%) | 206 | 265 | 77.7 |

| S3 | 38 (18.0%) | 36 (17.1%) | 29 (13.7%) | 41 (19.4%) | 36 (17.1%) | 31 (14.7%) | 211 | 266 | 79.3 |

| S4 | 46 (19.5%) | 42 (17.8%) | 52 (22.0%) | 34 (14.4%) | 29 (12.3%) | 33 (14.0%) | 236 | 293 | 80.5 |

| S5 | 50 (23.1%) | 41 (19.0%) | 33 (15.3%) | 28 (13.0%) | 29 (13.4%) | 35 (16.2%) | 216 | 277 | 77.9 |

| S6 | 36 (20.0%) | 18 (10.0%) | 28(15.6%) | 33 (18.3%) | 33 (18.3%) | 32 (17.8%) | 180 | 256 | 70.3 |

| S7 | 32 (14.3%) | 36 (16.1%) | 39 (17.4%) | 47 (21.0%) | 27 (12.1%) | 43 (19.2%) | 224 | 277 | 80.8 |

| S8 | 38 (16.1%) | 34 (14.4%) | 40 (16.9%) | 38 (16.1%) | 39 (16.5%) | 47 (19.9%) | 236 | 275 | 85.8 |

| S9 | 33 (15.3%) | 34 (15.7%) | 27 (12.5%) | 42 (19.4%) | 24 (11.1%) | 56 (25.9%) | 216 | 287 | 75.2 |

| Total | 334 | 314 | 296 | 336 | 279 | 346 | 1905 | 2450 | 77.7 |

Mean WTP

We calculated the unconditional mean WTP (adding the bid value only) and the conditional mean WTP in the three models (stepwise adding the sociodemographic characteristic covariate) and performed the scope test. Whichever scenario and parameter model is given, the difference in the WTP is not more than 5.5%, and the results of the scope tests have little difference (see Online Appendices 3 and 4), so only the unconditional mean WTP and its test results are reported in this text. Table 7 shows the mean WTP and related calculations in the four DBDC parameter models. The mean WTPs of the four parameter models with nine scenarios are in the ranges of ¥819.06–1115.22, ¥863.51–1141.88, ¥863.06–1115.22 and ¥871.08–1087.46, corresponding to logistic, normal, log-logistic and log-normal parameter models, respectively.

Table 7.

Unconditional mean willingness to pay (WTP) in four double-bounded dichotomous choice (DBDC) parameter models (unit: ¥)

| Model | Scenario | Mean WTP | SEa | 95% CIb | AIC | Log-likelihood |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic | S1 | 857 | 68.13 | [737–999] | 421.5 | − 208.8 |

| S2 | 1073 | 57.66 | [950–1299] | 425.4 | − 210.7 | |

| S3 | 896 | 62.93 | [777–1034] | 456.8 | − 226.4 | |

| S4 | 823 | 67.58 | [715–951] | 510.4 | − 253.2 | |

| S5 | 934 | 65.90 | [817–1070] | 408.1 | − 202.1 | |

| S6 | 819 | 69.19 | [710–951] | 380.1 | − 188.0 | |

| S7 | 840 | 62.69 | [731–969] | 500.0 | − 248.0 | |

| S8 | 888 | 58.53 | [785–1008] | 495.1 | − 245.5 | |

| S9 | 1115 | 54.28 | [987–1251] | 427.4 | − 211.7 | |

| Normal | S1 | 924 | 65.87 | [806–1058] | 420.6 | − 208.3 |

| S2 | 1108 | 59.60 | [989–1235] | 421.4 | − 208.7 | |

| S3 | 953 | 62.40 | [836–1086] | 455.6 | − 225.8 | |

| S4 | 898 | 63.41 | [791–1021] | 509.8 | − 252.9 | |

| S5 | 984 | 65.26 | [870–1113] | 404.9 | − 200.5 | |

| S6 | 864 | 69.03 | [752–993] | 380.4 | − 188.2 | |

| S7 | 898 | 61.45 | [789–1024] | 499.7 | − 247.9 | |

| S8 | 938 | 58.19 | [836–1055] | 493.3 | − 244.7 | |

| S9 | 1142 | 57.19 | [1020–1270] | 424.3 | − 210.1 | |

| Log-logistic | S1 | 863 | 71.72 | [734–1010] | 363.7 | − 179.9 |

| S2 | 1081 | 61.88 | [950–1218] | 384.5 | − 190.3 | |

| S3 | 914 | 66.44 | [785–1056] | 398.5 | − 197.2 | |

| S4 | 876 | 66.29 | [753–1015] | 440.0 | − 218.0 | |

| S5 | 959 | 67.64 | [829–1102] | 362.9 | − 179.5 | |

| S6 | 869 | 69.25 | [745–1011] | 352.0 | − 174.0 | |

| S7 | 890 | 63.51 | [768–1025] | 442.6 | − 219.3 | |

| S8 | 912 | 60.53 | [799–1037] | 444.0 | − 220.0 | |

| S9 | 1081 | 61.05 | [949–1218] | 384.0 | − 190.0 | |

| Log-normal | S1 | 885 | 71.79 | [754–1029] | 363.1 | − 179.5 |

| S2 | 1087 | 64.14 | [955–1223] | 384.9 | − 190.4 | |

| S3 | 931 | 67.83 | [801–1072] | 397.2 | − 196.6 | |

| S4 | 894 | 67.53 | [767–1032] | 438.0 | − 217.0 | |

| S5 | 969 | 69.31 | [837–1112] | 362.4 | − 179.2 | |

| S6 | 871 | 71.48 | [742–1013] | 351.5 | − 173.8 | |

| S7 | 903 | 65.27 | [780–1038] | 441.0 | − 218.5 | |

| S8 | 919 | 61.85 | [804–1044] | 442.1 | − 219.1 | |

| S9 | 1087 | 62.97 | [956–1222] | 382.1 | − 189.0 |

S2 and S9 had higher WTPs in the nine scenarios, and the highest WTP was approximately 30% higher than the lowest WTP. The WTPs in the normal parameter model were all higher (by approximately ¥26–75) than those in the logistic parameter model. The WTPs in the log-logistic and log-normal models were close, and most were between those in the other two parameter models. Table 7 reports the AIC and log-likelihood information of each model. The AIC and log-likelihood of the logistic and normal parameter models were similar, while those of the log-logistic and log-normal parameter models were close but smaller than those of the other two models. Therefore, the WTPs calculated by the log-normal parameter model were adopted as the final reported result in this paper.

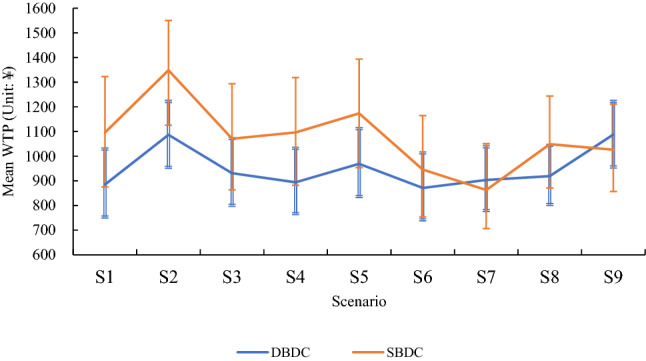

Figure 1 shows the WTPs of the SBDC and DBDC approaches, as well as the confidence intervals (CIs) in the log-normal parameter model. The WTPs of the SBDC technique were higher than those of the DBDC technique, except S7 and S9. The CIs in all nine SBDC scenarios were wider than those of the DBDC scenarios, indicating that the DBDC technique could estimate WTP more efficiently than could the SBDC technique.

Fig. 1.

Double-bounded dichotomous choice (DBDC) willingness to pay (WTP) versus single-bounded dichotomous choice (SBDC) WTP in the log-normal parameter model. The 95% confidence intervals with the Krinsky and Robb method are shown

Because the dichotomous choice technique requires the allocation of an approximately equal number of samples for each bid value [24], this paper considers the difference in each bid value sample’s proportion among the nine scenarios. Following Júdez’s method [44], we used random sampling with replacement to control the sample size to 30 under each bid value [45] and simulated WTP 1000 times, then taking the mean value. The results are shown in Table 8. It is clear that the real calculation results and simulated results are not very different, and the WTP distributions in the nine scenarios are relatively close; thus, this bias can be ignored.

Table 8.

Actual willingness to pay (WTP) versus simulated WTP in the log-normal parameter model (Unit: ¥)

| Scenario | Actual WTP | SE | Simulated WTP | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 885 | 71.79 | 867 | 70.73 |

| S2 | 1087 | 64.14 | 1099 | 75.30 |

| S3 | 931 | 67.83 | 940 | 78.13 |

| S4 | 894 | 67.53 | 910 | 73.06 |

| S5 | 969 | 69.31 | 971 | 75.51 |

| S6 | 871 | 71.48 | 881 | 69.68 |

| S7 | 903 | 65.27 | 923 | 79.59 |

| S8 | 919 | 61.85 | 915 | 74.41 |

| S9 | 1087 | 62.97 | 1110 | 82.06 |

Test Results

Table 9 shows that the proportion of respondents who answered “yes” decreased as the bid value increased. In the 20 pairs of COVID-19 vaccine scenarios, the six pairs of scenarios that belonged to the negative scope issue and were inconsistent with economic theory, therefore not passing the external scope test, were S2 versus S3, S2 versus S5, S2 versus S6, S5 versus S6, S2 versus S8 and S5 versus S8. The remaining 14 pairs of COVID-19 vaccine scenarios required scope tests to be conducted for further confirmation of scope insensitivity issues. The test result “reject” means that the WTP passes the test in the four parameter models; “not reject” means that no tests are passed in the four models; “mixed” means that some of the tests are passed in the four models.

Table 9.

Proportion of respondents answering “yes” to different bid values in the nine scenarios

| Scenario | By bid (unit: ¥) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 50 | 100 | 200 | 300 | 500 | 1000 | 2000 | |

| S1 | 100 | 93 | 97 | 82 | 68 | 54 | 54 | 29 |

| S2 | 100 | 97 | 91 | 86 | 78 | 71 | 63 | 32 |

| S3 | 100 | 97 | 96 | 75 | 73 | 58 | 53 | 32 |

| S4 | NaNa | 98 | 87 | 83 | 80 | 60 | 43 | 27 |

| S5 | 100 | 98 | 96 | 81 | 84 | 65 | 54 | 20 |

| S6 | NaN | 100 | 88 | 80 | 70 | 63 | 46 | 16 |

| S7 | NaN | 97 | 89 | 78 | 73 | 61 | 46 | 21 |

| S8 | NaN | 100 | 92 | 84 | 79 | 61 | 48 | 19 |

| S9 | NaN | 100 | 96 | 83 | 76 | 62 | 58 | 30 |

aNaN means that no respondents provided an answer under the bid value because all respondents responded “yes” to the initial bid value of ¥50 in the scenario

We first conducted a likelihood-ratio (LR) test [47] to examine whether there was a significant difference in the coefficients between the pooled sample model and the subsample model or whether all coefficients of the models varied between the nine subsamples. Table 10 shows that the LR test rejected only the null hypothesis at the 5% significance level in the logistic parameter model. None of the remaining three parameter models passed the LR test, i.e., the subsample observations should be combined rather than separated.

Table 10.

The likelihood-ratio (LR) test results

| Null hypothesis | Parameter modela | Test result | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic | Normal | Log-logistic | Log-normal | ||

| βsubsamples = βpooled | 28.43* | 25.58 | 17.53 | 6.46 | Mixed |

*p < 0.05

aLR test statistic is , where and are the log-likelihood of the pooled sample and the Si subsample (i = 1, 2 … 9), respectively

Fourteen pairs of vaccines were statistically tested by the complete combinatorial (CC) test, which calculates significance by convolution of two WTP CIs [48]. As shown in Table 11, four pairs of vaccine scenarios (S1 vs S2, S6 vs S9, S7 vs S9 and S1 vs S9) rejected the null hypothesis in the four parameter models and passed the statistical test. The null hypothesis of S5 versus S9 was rejected only in the logistic and normal parameter models, so the test result was mixed. In addition, we used the method of adding a dummy variable to distinguish the subsample observations for two scenarios as an additional hypothesis test. A one-tailed t-test for the dummy variable was conducted due to the known WTP size relationship [49, 50]. The test results were close to the CC test results, except that (1) S1 versus S9 failed to pass the test in the normal parameter model (the p value was 0.051) and the test result was mixed and (2) S5 versus S9 failed to pass the test in the four parameter models (Online Appendix 4).

Table 11.

The complete combinatorial (CC) external scope test results

| Category | Null hypothesisa | Parameter modelb | Test result | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic | Normal | Log-logistic | Log-normal | |||

| I | WTP[S2] = WTP[S1] | 0.013 | 0.023 | 0.015 | 0.022 | Rejected |

| I | WTP[S7] = WTP[S1] | 0.659 | 0.614 | 0.391 | 0.424 | Not rejected |

| I | WTP[S9] = WTP[S6] | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.016 | 0.015 | Rejected |

| I | WTP[S9] = WTP[S7] | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.024 | 0.028 | Rejected |

| II | WTP[S3] = WTP[S1] | 0.341 | 0.373 | 0.305 | 0.322 | Not rejected |

| II | WTP[S4] = WTP[S1] | 0.646 | 0.616 | 0.447 | 0.463 | Not rejected |

| II | WTP[S5] = WTP[S1] | 0.206 | 0.252 | 0.167 | 0.200 | Not rejected |

| II | WTP[S6] = WTP[S1] | 0.659 | 0.749 | 0.476 | 0.556 | Not rejected |

| II | WTP[S8] = WTP[S4] | 0.218 | 0.310 | 0.345 | 0.390 | Not rejected |

| II | WTP[S8] = WTP[S7] | 0.208 | 0.312 | 0.402 | 0.429 | Not rejected |

| II | WTP[S9] = WTP[S1] | 0.005 | 0.010 | 0.016 | 0.021 | Rejected |

| II | WTP[S9] = WTP[S2] | 0.329 | 0.353 | 0.500 | 0.497 | Not rejected |

| II | WTP[S9] = WTP[S5] | 0.030 | 0.042 | 0.110 | 0.116 | Mixed |

| III | WTP[S8] = WTP[S1] | 0.361 | 0.432 | 0.300 | 0.356 | Not rejected |

aThe null hypothesis here is different from the hypothesis in Table 3 because the latter is an alternative hypothesis. If the null hypothesis is rejected, the alternative hypothesis is supported, i.e., it passes the scope test, and vice versa

bThe significance of the CC test is , in which and are the results of the Krinsky and Bobb method with 5000 draws in two scenarios SX and SY, and the vaccine in scenario SY is better than that in scenario SX [48]

Discussion

This paper identified nine hypothetical COVID-19 vaccine CV scenarios by selecting different vaccine attributes using an orthogonal experimental design and estimated respondents’ WTP for vaccines. The result of the log-normal parameter model showed that the mean WTP for the nine vaccine scenarios was in the range of ¥871.08–1087.46, which was relatively similar to the $184.72 and $232 WTP result in Chile [14, 15], higher than the $57 WTP result in Indonesia [16], higher than the $85.92 WTP result in southern Vietnam [18] and higher than the ¥254 WTP result in China [19] but lower than the $318.8–424.6 range in Ecuador [17]. There are many factors that contribute to the variation in WTP, including differences in economic levels, cultures and ethnic habits between countries, and the different outbreak conditions of COVID-19 at different moments can also lead to changes in the WTP [17]. Ecuador’s high WTP may be attributed to a sharp increase in confirmed cases of and deaths from COVID-19 during the investigation period. The main reason for the difference between our WTP and that of another Chinese study may be the different durations of COVID-19 [17], as the latter occurred only three months after COVID-19 emerged, while we conducted the survey more than 1 year into the COVID-19 pandemic. The long global outbreak and severe situation it has caused have increased individuals’ sense of urgency and serious awareness of COVID-19, so the WTP for the COVID-19 vaccine would be relatively high, which is consistent with the two studies in Chile performed at different times [14, 15]. In general, the public’s WTP for the COVID-19 vaccine is higher than that of previously studied vaccines for other diseases, such as the pneumococcal vaccine in Bangladesh ($2.34–18), the dengue vaccine in Vietnam, Thailand and Colombia ($23–70.3) and the Zika one-dose vaccine in Brazil ($56.41) [6, 9, 51]. The high public WTP for the COVID-19 vaccine reflects the perception of the severity of the COVID-19 virus, which has a high infection rate and a wide range of transmission.

Due to the randomness of the electronic questionnaire, it is difficult to ensure the same number of subsamples in each scenario. Júdez et al. [44] through the use of Monte Carlo simulation, showed that when the sample size reaches 400, the impact of the number of bid values and sample size on WTP becomes very small. Although our subsample size did not reach this number, we controlled the consistency of the sample size of each scenario by sampling with replacement. We found that there was still no obvious change in the WTP (Table 8). Therefore, the existence of the issue of scope would not be attributed to the imbalance of subsample size. To ensure the validity and reliability of the CV estimates of the respondents’ WTP for the COVID-19 vaccine, we conducted several types of external scope tests. In the first test, almost all nine scenarios were in line with the simple hypothesis of falling demand with rising prices. However, in the second test, where the WTP for a better vaccine should be higher than that for a suboptimal vaccine, six pairs of vaccines failed to pass the test, producing a negative scope issue. At present, it is difficult to further explain the negative marginal utility of the attribute scope, especially the vaccine attribute scope. In the statistical scope test, the LR test results were partially consistent with those of previous studies [52, 53], indicating the lack of validity of the respondents’ responses to the nine different scenarios [54].

From the category I to category III hypotheses, the number of attribute differences between two vaccines ranged from 1 to 3, which could be regarded as the growing scope of attributes. The results suggested that 3 of the 4 category I hypotheses passed the test; only 1 of the 9 category II hypotheses passed the test, and 1 was mixed; and only 1 category III hypothesis failed to pass the test. With the expansion of scope, the issue of respondents’ scope insensitivity becomes more serious. It is worth noting that most of the hypothesis tests associated with S9 passed, indicating people’s preference for a COVID-19 vaccine with high effectiveness and a long duration of protection. In previous CV method studies of scope issues in terms of vaccines, researchers mostly chose one difference in the level of one attribute as a change in scope, such as the category I hypothesis in this paper, e.g., changing the degree of risk of death reduced after vaccination [34–36], changing the duration of vaccine protection [35, 37] or changing the description of disease symptoms [34].

This scope issue poses a crucial challenge to the validity and reliability of the CV method in evaluating the public’s WTP for the COVID-19 vaccine. One possible explanation for the failure of the external scope test is that as the COVID-19 outbreak continues to evolve, respondents’ donations are driven more by the urgency of the pandemic than by the reliability and attractiveness of vaccine alternatives. The COVID-19 outbreak is not over, people’s WTP for the vaccine will fluctuate as the pandemic develops, and future studies can focus on evaluating the WTP for the COVID-19 vaccine over multiple periods.

Conclusions

The results of the external scope tests revealed that there were apparent negative scope effects and scope insensitivity in respondents’ WTP for the COVID-19 vaccine. We suggest that future studies should be cautious in applying the CV method to estimate the WTP of the COVID-19 vaccine, especially in terms of cost-benefit analysis.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No.17BGL247), Marine “Boutique Tourism” Innovative Team Project of Shandong Province (Grant No.057). The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Declarations

Funding

This study was funded by the National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No.17BGL247) and Marine “Boutique Tourism” Innovative Team Project of Shandong Province (Grant No.057).

Conflicts of interest

Jianhong Xiao, Yihui Wu, Min Wang and Zegang Ma have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Availability of data and material

The datasets that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all the respondents included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

Jianhong Xiao: overall research design and paper writing, Yihui Wu: data processing and paper writing, Min Wang: data collection and data processing, Zegang Ma: paper writing and questionnaire design.

Footnotes

See the Wenjuanxing website at http://www.wjx.cn.

Vaccine effectiveness refers to the percentage reduction in the incidence rate of COVID-19 among vaccinated individuals in comparison to nonvaccinated individuals.

The duration of protection refers to the length of time that the vaccine induces individual immunity.

Side effects refer to harmful reactions caused by the characteristics of the vaccine itself.

Mild adverse reactions mainly manifest as local pain, redness and swelling at the inoculation location, as well as transient low fever, fever, and so on. Transient refers to a clinical symptom or sign that appears once in a short period of time, often with obvious triggers.

Scenario randomisation means that all nine scenarios are included in the design of the electronic questionnaire, but only one scenario appears randomly in the actual questionnaire, and the occurrence of scenarios is completely randomly assigned by the system.

Bid value randomisation means that six initial bid values are uniformly entered into the design of the electronic questionnaire, but only one is randomly selected in the actual questionnaire.

Contributor Information

Jianhong Xiao, Email: xiaojian_hong@163.com.

Yihui Wu, Email: wuyihui97@126.com.

Min Wang, Email: wang_min1981@163.com.

Zegang Ma, Email: mazegang@qdu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.World Health Organization: SARS-CoV-2 Variants. (2020). https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2020-DON305. Accessed 6 Jun 2021.

- 2.World Health Organization: WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. (2021). https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed 6 Jun 2021.

- 3.National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China: Information Disclosure. (2021). http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/yqtb/202106/c8576813374d4238bf7ec7f29ce75bbe.shtml. Accessed 6 Jun 2021.

- 4.Zhang L, Liu YH. Potential interventions for novel coronavirus in China: a systematic review. J Med Virol. 2020;92(5):479–490. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China: News (2021). http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-01/10/content_5578578.htm. Accessed 26 Aug 2021.

- 6.Lee JS, Mogasale V, Lim JK, Carabali M, Sirivichayakul C, Anh DD, et al. A multi-country study of the household willingness-to-pay for dengue vaccines: household surveys in Vietnam, Thailand, and Colombia. Plos Neglect Trop Dis. 2015;9(6):e0003810. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nguyen LH, Tran BX, Do CD, Hoang CL, Nguyen TP, Dang TT, et al. Feasibility and willingness to pay for dengue vaccine in the threat of dengue fever outbreaks in Vietnam. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:1917–1926. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S178444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vo TQ, Tran QV, Vo NX. Customers’ preferences and willingness to pay for a future dengue vaccination: a study of the empirical evidence in Vietnam. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:2507–2515. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S188581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heinzen RR, Bridges JFP. Comparison of four contingent valuation methods to estimate the economic value of a pneumococcal vaccine in Bangladesh. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2008;24(4):481–487. doi: 10.1017/S026646230808063X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hou ZY, Chang J, Yue DH, Fang H, Meng QY, Zhang YT. Determinants of willingness to pay for self-paid vaccines in China. Vaccine. 2014;32(35):4471–4477. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cook J, Whittington D, Canh DG, Johnson FR, Nyamete A. Reliability of stated preferences for cholera and typhoid vaccines with time to think in Hue, Vietnam. Econ Inq. 2007;45(1):100–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-7295.2006.00038.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Islam Z, Maskery B, Nyamete A, Horowitz MS, Yunus M, Whittington D. Private demand for cholera vaccines in rural Matlab, Bangladesh. Health Policy. 2008;85(2):184–195. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim D, Canh DG, Poulos C, Thoa LTK, Cook J, Hoa NT, et al. Private demand for cholera vaccines in Hue, Vietnam. Value Health. 2008;11(1):119–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.García LY, Cerda AA. Contingent assessment of the COVID-19 vaccine. Vaccine. 2020;38(34):5424–5429. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.06.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cerda AA, García LY. Willingness to pay for a COVID-19 vaccine. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2021;19(3):342–351. doi: 10.1007/s40258-021-00644-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harapan H, Wagner AL, Yufika A, Winardi W, Anwar S, Gan AK, et al. Willingness-to-pay for a COVID-19 vaccine and its associated determinants in Indonesia. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2020;16(12):3074–3080. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1819741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarasty O, Carpio CE, Hudson D, Guerrero-Ochoa PA, Borja I. The demand for a COVID-19 vaccine in Ecuador. Vaccine. 2020;38(51):8090–8098. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vo NX, Huyen Nguyen TT, Van Nguyen P, Tran QV, Vo TQ. Using contingent valuation method to estimate adults’ willingness to pay for a future coronavirus 2019 vaccination. Value Health Reg Issues. 2021;24:240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.vhri.2021.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang JH, Lyu Y, Zhang HJ, Jing RZ, Lai XZ, Feng HYF, et al. Willingness to pay and financing preferences for COVID-19 vaccination in China. Vaccine. 2021;39(14):1968–1976. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.02.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hausman J. Contingent valuation: from dubious to hopeless. J Econ Perspect. 2012;26(4):43–56. doi: 10.1257/jep.26.4.43. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carson RT, Mitchell RC. The issue of scope in contingent valuation studies. Am J Agric Econ. 1993;75(5):1263–1267. doi: 10.1177/107808749703200502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schkade DA, Payne JW. How people respond to contingent valuation questions: a verbal protocol analysis of willingness to pay for an environmental regulation. J Environ Econ Manag. 1994;26(1):88–109. doi: 10.1006/jeem.1994.1006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Desvousges W, Mathews K, Train K. Adequate responsiveness to scope in contingent valuation. Ecol Econ. 2012;84:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitchell RC, Carson RT. Using surveys to value public goods. 4. Washington: Resources for the Future; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carson RT. Contingent valuation: a practical alternative when prices aren’t available. J Econ Perspect. 2021;26(4):27–42. doi: 10.1257/jep.26.4.27. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whitehead JC. Plausible responsiveness to scope in contingent valuation. Ecol Econ. 2016;128:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.03.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Desvousges WH, Johnson FR, Dunford RW, Hudson SP, Wilson KN, Boyle KJ. Contingent valuation: as critical assessment. 1. Amsterdam: North Holland; 1993. Measuring natural resource damages with contingent valuation: tests of validity and reliability. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klose T. The contingent valuation method in health care. Health Policy. 1999;47:97–123. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8510(99)00010-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arrow K, Solow R, Portney PR, Leamer EE, Radner R, Schuman H. Report of the NOAA panel on contingent valuation. Fed Regist. 1993;58(10):4601–4614. doi: 10.1002/qj.49703213905. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giraud KL, Loomis JB, Johnson RL. Internal and external scope in willingness-to-pay estimates for threatened and endangered wildlife. J Environ Manag. 1999;56:221–229. doi: 10.1006/jema.1999.0277. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carson RT, Mitchell RC. Sequencing and nesting in contingent valuation surveys. J Environ Econ Manag. 1995;28:155–173. doi: 10.1006/jeem.1995.1011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carson RT, Flores NE, Meade NF. Contingent valuation: controversies and evidence. Environ Resour Econ. 2001;19:173–210. doi: 10.1023/A:1011128332243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yeung RYT, Smith RD, McGhee SM. Willingness to pay and size of health benefit: an integrated model to test for ‘sensitivity to scale’. Health Econ. 2003;12:791–796. doi: 10.1002/hec.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carlson D, Haeder S, Jenkins-Smith H, Ripberger J, Silva C, Weimer D. Monetizing bowser: a contingent valuation of the statistical value of dog life. J Benefit Cost Anal. 2019;11(1):131–149. doi: 10.1017/bca.2019.33. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu JT, Hammitt JK, Wang JD, Tsou MW. Valuation of the risk SARS in Taiwan. Health Econ. 2005;14(1):83–91. doi: 10.1002/hec.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Odihi D, De Broucker G, Hasan Z, Ahmed S, Constenla D, Uddin J, et al. Contingent valuation: a pilot study for eliciting willingness to pay for a reduction in mortality from vaccine-preventable illnesses for children and adults in Bangladesh. Value Health Reg Issues. 2021;24:67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.vhri.2020.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palanca-Tan R. The demand for a dengue vaccine: a contingent valuation survey in Metro Manila. Vaccine. 2008;26(7):914–923. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shiell A, Gold L. Contingent valuation in health care and the persistence of embedding effects without the warm glow. J Econ Psychol. 2002;23(2):251–262. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4870(02)00066-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mohammadi E, Shafiee F, Shahzamani K, Ranjbar MM, Alibakhshi A, Ahangarzadeh S, et al. Novel and emerging mutations of SARS-CoV-2: biomedical implications. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;139:111599. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heberlein TA, Wilson MA, Bishop RC, Schaeffer NC. Rethinking the scope test as a criterion for validity in contingent valuation. J Environ Econ Manag. 2005;50:1–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jeem.2004.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harapan H, Anwar S, Bustamam A, Radiansyah A, Angraini P, Fasli R, et al. Willingness to pay for a dengue vaccine and its associated determinants in Indonesia: a community-based, cross-sectional survey in Aceh. Acta Trop. 2017;166:249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2016.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rajamoorthy Y, Radam A, Taib NM, Ab Rahim K, Munusamy S, Wagner AL, et al. Willingness to pay for hepatitis B vaccination in Selangor, Malaysia: a cross-sectional household survey. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(4):e0215125. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hanemann WM. Welfare evaluations in contingent valuation experiments with discrete response data: Reply. Am J Agric Econ. 1989;71(4):1057–1061. doi: 10.2307/1242685. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Júdez L, de Andrés R, Hugalde CP, Urzainqui E, Ibañez M. Influence of bid and subsample vectors on the welfare measure estimate in dichotomous choice contingent valuation: evidence from a case-study. J Environ Manag. 2000;60(3):253–265. doi: 10.1006/jema.2000.0380. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strawderman WE, Lehmann EL, Holmes SP. Elements of large-sample theory. 1. Berlin: Springer; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krinsky I, Robb AL. On approximating the statistical properties of elasticities. Rev Econ Stat. 1986;68(4):715–719. doi: 10.2307/1924536. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Veisten K, Hoen HF, Navrud S, Strand J. Scope insensitivity in contingent valuation of complex environmental amenities. J Environ Manag. 2004;73(4):317–331. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Poe GL, Giraud KL, Loomis JB. Computational methods for measuring the difference of empirical distributions. Am J Agric Econ. 2005;87(2):353–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8276.2005.00727.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jin JJ, Indab A, Nabangchang O, Thuy TD, Harder D, Subade RF. Valuing marine turtle conservation: a cross-country study in Asian cities. Ecol Econ. 2010;69(10):2020–2026. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.05.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Loomis JB, Hung LT, González-Cabán A. Willingness to pay function for two fuel treatments to reduce wildfire acreage burned: a scope test and comparison of White and Hispanic households. For Policy Econ. 2009;11(3):155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2008.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Muniz Júnior RL, Godói IP, Reis EA, Garcia MM, Guerra Júnior AA, Godman B, et al. Consumer willingness to pay for a hypothetical Zika vaccine in Brazil and the implications. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2019;19(4):473–482. doi: 10.1080/14737167.2019.1552136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Borzykowski N, Baranzini A, Maradan D. Scope effects in contingent valuation: does the assumed statistical distribution of WTP matter? Ecol Econ. 2018;144:319–329. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hammar H, Johansson-Stenman O. The value of risk-free cigarettes—do smokers underestimate the risk? Health Econ. 2004;13(1):59–71. doi: 10.1002/hec.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kniivilä M. Users and non-users of conservation areas: Are there differences in WTP, motives and the validity of responses in CVM surveys? Ecol Econ. 2006;59(4):530–539. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2005.11.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.