Abstract

Background

Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a pivotal cellular phenomenon involved in tumour metastasis and progression. In gastric cancer (GC), EMT is the main reason for recurrence and metastasis in postoperative patients. Acacetin exhibits various biological activities. However, the inhibitory effect of acacetin on EMT in GC is still unknown. Herein, we explored the possible mechanism of acacetin on EMT in GC in vitro and in vivo.

Methods

In vitro, MKN45 and MGC803 cells were treated with acacetin, after which cell viability was detected by CCK-8 assays, cell migration and invasion were detected by using Transwell and wound healing assays, and protein expression was analysed by western blots and immunofluorescence staining. In vivo, a peritoneal metastasis model of MKN45 GC cells was used to investigate the effects of acacetin.

Results

Acacetin inhibited the proliferation, invasion and migration of MKN45 and MGC803 human GC cells by regulating the expression of EMT-related proteins. In TGF-β1-induced EMT models, acacetin reversed the morphological changes from epithelial to mesenchymal cells, and invasion and migration were limited by regulating EMT. In addition, acacetin suppressed the activation of PI3K/Akt signalling and decreased the phosphorylation levels of TGF-β1-treated GC cells. The in vivo experiments demonstrated that acacetin delayed the development of peritoneal metastasis of GC in nude mice. Liver metastasis was restricted by altering the expression of EMT-related proteins.

Conclusion

Our study showed that the invasion, metastasis and TGF-β1-induced EMT of GC are inhibited by acacetin, and the mechanism may involve the suppression of the PI3K/Akt/Snail signalling pathway. Therefore, acacetin is a potential therapeutic reagent for the treatment of GC patients with recurrence and metastasis.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12906-021-03494-w.

Keywords: Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), Acacetin, Gastric cancer (GC), TGF-β1, Metastasis

Background

Gastric cancer (GC) has the fifth highest incidence worldwide and the third highest mortality rate [1]. The prognosis of GC is poor because most patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage or because frequent recurrence and distant metastasis occur after surgical resection [2]. Peritoneal metastasis is the most common pattern of GC after standard radical resection, and the median survival time of patients is very short [3]. Moreover, the liver is the most common site of haematogenous metastasis of GC, and up to 37% of GC patients developed hepatic metastases after radical gastrectomy [4]. After metastasis in GC, fewer effective treatments are available.

EMT is a reversible cellular process that transiently places epithelial cells into quasi-mesenchymal cell states [5]. This process facilitates the motility of adherent epithelial cells and endows cells with migratory properties via reduced adhesion and added invasive capacity; most importantly, the mesenchymal state is associated with the capacity of cells to migrate to distant organs during metastasis [6, 7]. Indeed, tumours often express EMT markers or lose epithelial markers prior to the invasive process and extravasation of circulating tumour cells [8]. Many factors, such as TGF-β, epidermal growth factor, fibroblast growth factor, Notch pathways, cytokines, extracellular matrix components or mechanotransduction, can induce EMT [9–13]. In response to these extracellular signals, epithelial cells achieve dramatic changes in motility.

Transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) is the ligand of the TGF-β receptor complex, and activation of the TGF-β signalling pathway plays a crucial role in many biological programs, such as the genesis, development and metastasis of tumours [14, 15]. TGF-β signalling was also shown to play a central role in EMT [16], where it activates SMADs and collaborates with other signalling cascades, such as ERK, p38 MAPK and PI3K/Akt [17, 18]. The PI3K/Akt pathway can regulate cell proliferation and maintain malignant biological behaviour [19]. Activation of this pathway is a central feature in EMT [20]. Therefore, PI3K/Akt pathway-mediated EMT has led to continuing concern, as it acts as a possible target for the prevention and treatment of metastatic tumours.

Acacetin (5,7-dihydroxy-4′-methoxyflavone) is a flavone that is widely present in various plants, such as black locust, Pseudostellaria heterophylla, Chrysanthemum indicum, and patchouli. This molecule exhibits various biological activities, including anticancer, antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimalarial, antiobesity, and vasorelaxant activities [21–23]. Previous studies have shown that acacetin inhibits invasion and metastasis in various cancer cell lines, including lung cancer and prostate cancer cell lines [24–26]. In breast cancer cells, acacetin was shown to inhibit cell adhesion, focal adhesion formation and migration in a concentration-dependent manner [27]. However, the role of acacetin in EMT in GC is still unclear. In this study, we elucidated the anticancer mechanism of acacetin in GC in vitro and in vivo.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Acacetin (purity 98%) was purchased from Tauto Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). RPMI 1640 medium was obtained from Gibco (Beijing, China). Foetal bovine serum was purchased from Gibco (CA, USA). Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) reagent was purchased from Dojindo (Dojindo Laboratories, Japan). TGF-β1 was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Anti-p-PI3K (Tyr458), anti-p-Akt (Ser473), anti-PI3K and anti-Akt were purchased from Affinity Biosciences. Anti-MMP-9, anti-MMP-2 and anti-Snail were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Anti-Vimentin, anti-N-cadherin, anti-E-cadherin, anti-GAPDH, and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies were obtained from Proteintech (Wuhan, China).

Cell lines

The human GC cell lines MKN45 and MGC803 were purchased from the Shanghai Institute of Cell Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). The cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% foetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

Cell viability assay

The viability of the GC cell lines MKN45 and MGC803 was detected by CCK-8 assays. Acacetin was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) at a concentration less than 3‰. MKN45 and MGC803 cells were uniformly plated in 96-well plates at a density of 3 × 103 cells/well. The cells were treated with different concentrations of acacetin (from 0 to 100 μM). Then, the cytotoxicity of the cells cultured with acacetin was assessed at 24, 48, and 72 h. CCK-8 solution (10 μl/well) was incubated for 1 h, and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek, America).

Migration and invasion assays

For the migration assay, the cells (2 × 104) were collected and seeded in the upper chamber (8 μm) in 24-well plates (Corning) with 300 μl of serum-free medium containing acacetin (40 μM) or 10 ng/ml TGF-β1. For invasion experiments, diluted (1:3) basement Matrigel was added to each chamber and allowed to polymerize at 37 °C for 30 min. The cells (1 × 105) were seeded in the upper chamber with 300 μl of serum-free medium containing acacetin (40 μM) or 10 ng/ml TGF-β1. FBS medium (20%) was added to the lower chamber of the Transwell. After incubation for 24 h, cells on the top of the chamber were removed with cotton swabs, and the migrated cells were stained with 0.5% crystal violet. The Transwell was photographed under a microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) at 20× magnification. Five fields were randomly selected for quantification. The number of invasive cells was counted according to the cell morphology because the nucleus was clearly visible.

Wound healing assay

MKN45 and MGC803 cells were cultured in 6-well plates overnight. The cell monolayers were wounded by scratching with 10 μl sterile pipette tips and washed with PBS. Fresh serum-free medium containing TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml) with or without acacetin (40 μM) was added to the plates, and then, the cells were cultured for 24 h at 37 °C. Images of the different stages of wound healing were obtained via microscopy at different time intervals. The wounded areas were quantified by wound width using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Immunofluorescence staining

The cells were seeded in glass bottom cell culture dishes (Nest), treated with acacetin (40 μM), fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 30 min, and then washed three times with PBS. BSA (2%) in PBS was used to block the cells for 1 h, and the cells were incubated with primary antibodies (E-cadherin 1:200; N-cadherin 1:200) overnight at 4 °C, washed three times with PBS, and incubated with FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:200 dilution, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 2 h. Nuclear staining was performed with 1 μg/ml 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Images were examined with a fluorescence microscope.

Western blot

For western blot analysis, total protein samples were extracted from MKN45 or MGC803 cells, and liver metastatic tumour tissues were collected from nude mice using a protease inhibitor to break up the cells in a homogenizer. An equal amount of protein (30 μg/lane) was loaded on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and then transferred to a pure polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Some membranes were cut according to the molecular weight of the test proteins. Next, the membrane was blocked in 5% nonfat milk for 1.5 h and then probed with primary antibodies against PI3K, p-PI3K, Akt, p-Akt, Snail, E-cadherin, N-cadherin, Vimentin, MMP2, MMP9, and GAPDH. Then, the membranes were incubated with anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies for 2 h. Finally, immunoreactivity was detected using the Tanon Imaging System (Shanghai, China). The densitometric estimations were quantified using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). All of the raw data using western blotting were supplemented in Figs. S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S6 and S7.

Animal experiments

The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All experiments were conducted following the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals approved by Longhua Hospital, Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (LHERAW-2003). Male BALB/c nude mice (21–25 g weight; 4–6 weeks old) were purchased from GemPharmatech Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China) and maintained in specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions in accordance with institutional policies. The mice received sterile rodent chow and water ad libitum and were housed in sterile filter-top cages with 12-h light/dark cycles. Human MKN45 cells were collected, resuspended in PBS and injected intraperitoneally into the mice (2 × 106 cells/mouse, n = 5). The mice were regularly fed. On the 8th day after modelling, acacetin was administered intraperitoneally. Acacetin was dissolved in DMSO and diluted with cyclodextrin at the time of injection, and the concentration of DMSO was not greater than 5%. Nude mice were divided into three groups: the control group (solvent only), acacetin low-dose group (25 mg/kg) and acacetin high-dose group (50 mg/kg). The frequency of administration was once every two days. During the experiments, the body weight of each mouse was measured 2–3 times every week. The mice were sacrificed approximately 3 weeks later, the abdominal colonized tumours were counted, and the number of metastatic nodules in the livers was observed. The histological features of liver metastatic nodules in different groups of mice were analysed through routine pathological staining.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t-test for two group comparisons. GraphPad Prism 5.0 was used for statistical analyses. A value *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 or ***p < 0.001 and # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, or ### p < 0.001 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Acacetin inhibited the proliferation, invasion and migration of MKN45 and MGC803 cells

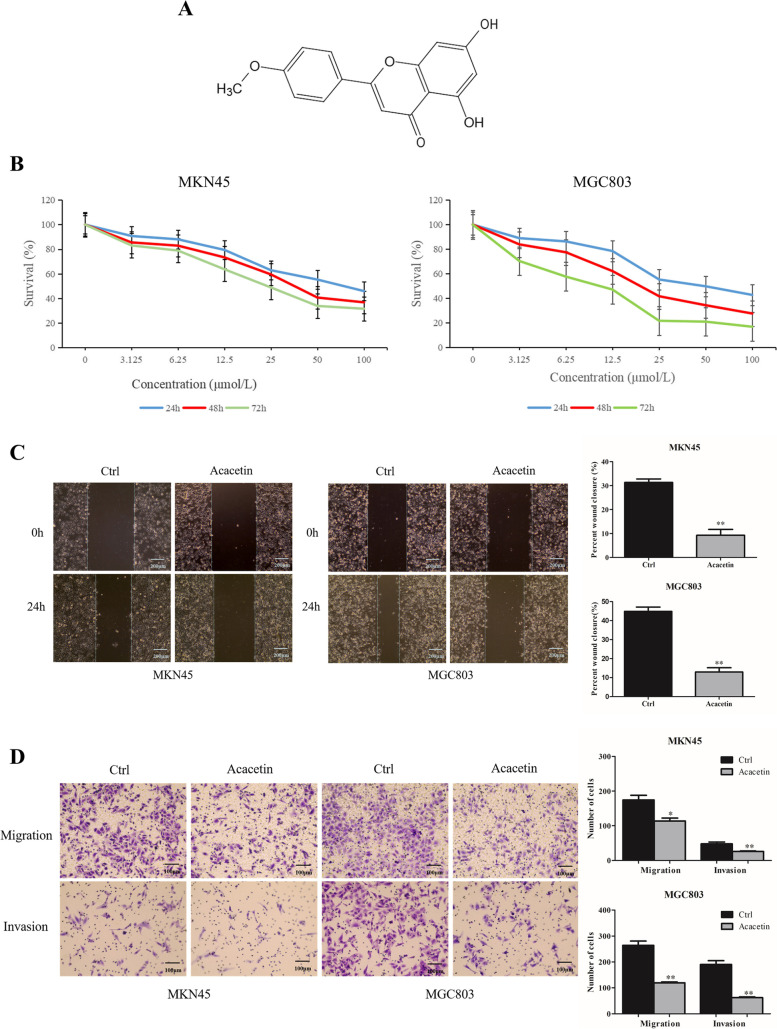

We first investigated the effects of acacetin (Fig. 1A) on cell growth. GC cells were treated with different concentrations of acacetin from 0 to 100 μM for 24, 48 and 72 h, and cell viability was detected at different time points. As shown in Fig. 1B, the half maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50) of MKN45 cells were 54.092 μM, 45.017 μM, and 36.961 μM at 24, 48 and 72 h, respectively. The IC50 of MGC803 cells was 48.357 μM, 33.449 μM, and 19.968 μM at 24, 48 and 72 h, respectively. Acacetin inhibited the proliferation of both MKN45 and MGC803 cells in a time- and dose-dependent manner. MGC803 cells were more sensitive to acacetin than MKN45 cells. Therefore, the optimal inhibitory concentration of MKN45 cells was 45 μM, and that of MGC803 cells was 33 μM.

Fig. 1.

Effects of acacetin on the survival and invasion of MKN45 and MGC803 cells. A The chemical structure of acacetin. B MKN45 and MGC803 cells were treated with 0–100 μM acacetin for 24–72 h and subjected to CCK-8 assays. C A wound healing assay was performed to evaluate the antimetastatic effect of acacetin in MKN45 and MGC803 cells (magnification, 10×). D Transwell migration and Matrigel invasion assays of MKN45 and MGC803 cells treated with or without acacetin were performed (magnification, 20×)

The scratch assay is a well-developed method to detect cell migration in vitro [28]. In this study, we established two groups: a blank control group and an acacetin group. Acacetin (40 μM and 30 μM) was added to MKN45 and MGC803 cells, respectively. As shown in Fig. 1C (p < 0.05), the migration rate of GC cells was reduced after treatment with acacetin. In the cell invasion and migration assays, the number of cells migrating to the membrane in the acacetin group was significantly lower than that in the control group (p < 0.05, Fig. 1D). These results indicated that acacetin can inhibit the metastasis of GC cells.

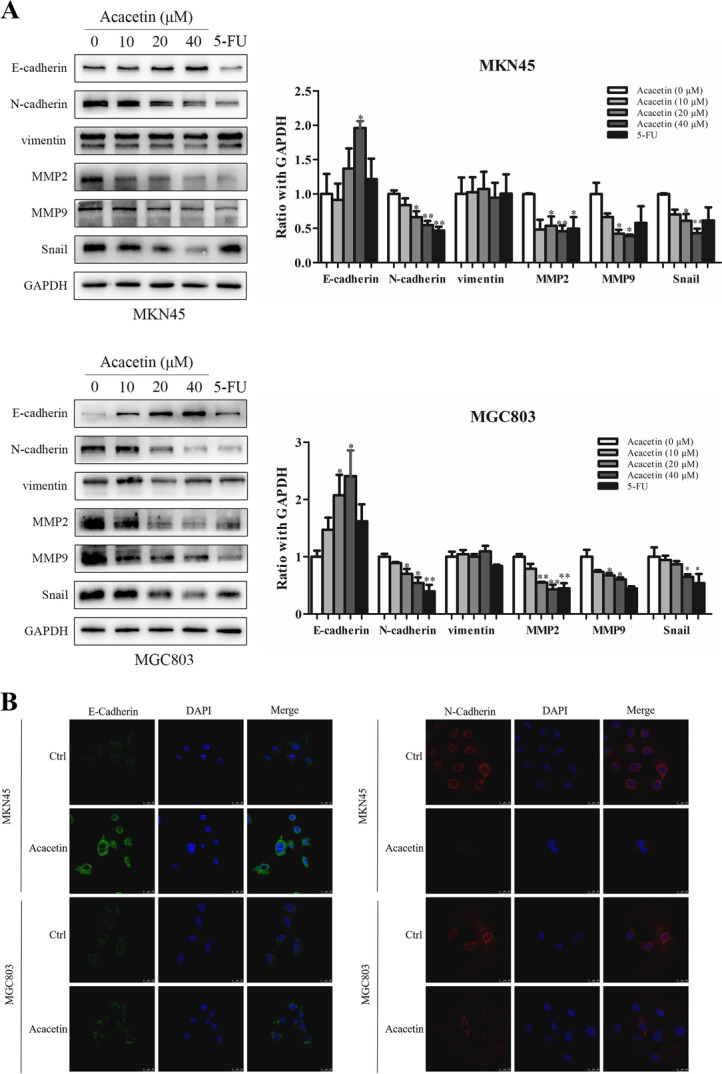

Acacetin regulated the expression of EMT-related biomarkers in MKN45 and MGC803 cells

EMT is characterized by reduced E-cadherin expression and increased mesenchymal markers (such as N-cadherin and Vimentin), transcription factors (Twist, Slug and Snail) and MMPs [29]. In our study, GC cells were incubated with different concentrations of acacetin (10, 20, and 40 μm for MKN45 and 7.5, 15, and 30 μm for MGC803) for 48 h. The results showed that the expression of the epithelial marker E-cadherin was upregulated and that of the mesenchymal marker N-cadherin was downregulated, although Vimentin expression did not change (p < 0.05, Fig. 2A). In addition, compared with the control, acacetin treatment downregulated EMT-related Snail and metastasis-related MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression. Interestingly, some markers showed significant dose-dependent characteristics. In addition, immunofluorescence staining showed that E-cadherin expression was increased and N-cadherin expression was decreased in the GC cells treated with acacetin (p < 0.05, Fig. 2B). These findings indicated that acacetin inhibits EMT-related proteins.

Fig. 2.

Effect of acacetin on EMT in MKN45 and MGC803 cells. A The protein expression levels of EMT biomarkers (E-cadherin, N-cadherin, Vimentin, MMP-9, MMP-2 and Snail) were determined by western blot analysis. B MKN45 and MGC803 cells were treated with acacetin for 24 h. Then, the cells were fixed and labelled for E-cadherin (green) and N-cadherin (red), and the nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). The third parts show the merged images. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 3). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 compared to the vehicle control

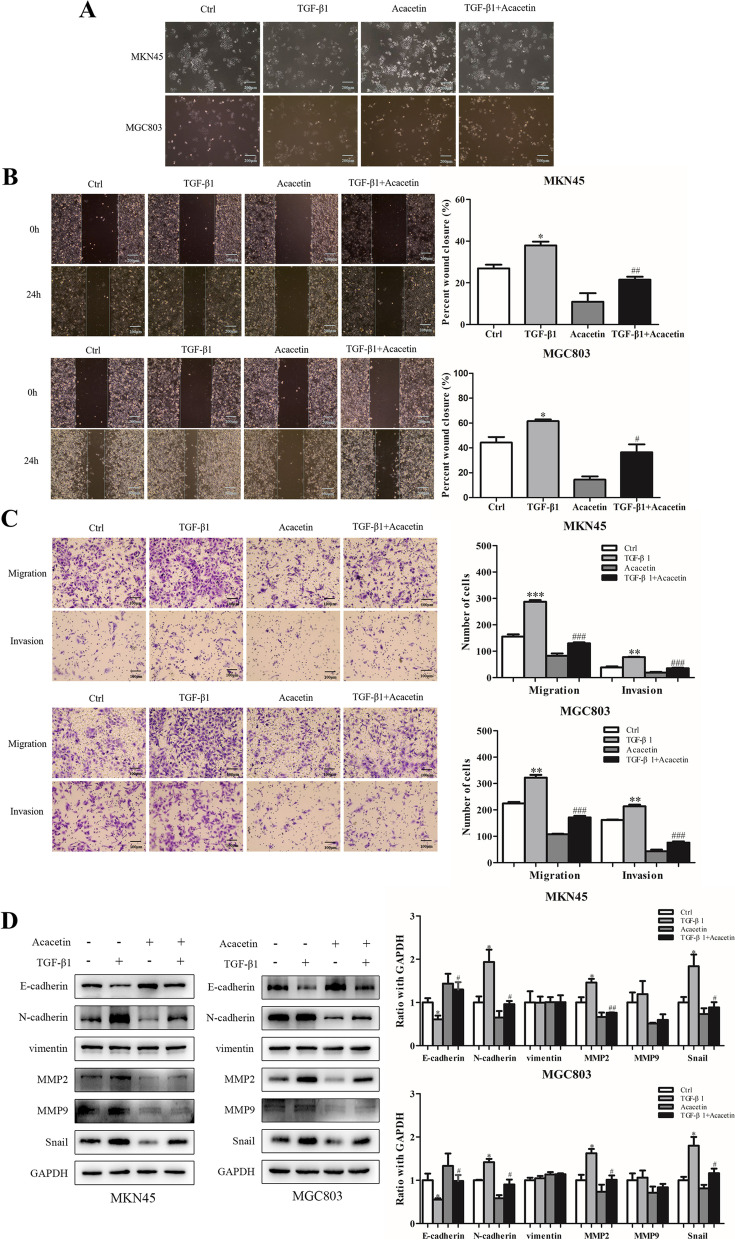

Acacetin inhibited TGF-β1-induced EMT of MKN45 and MGC803 cells

TGF-β1 can activate EMT in a variety of tumour cells [30]. Therefore, we explored whether acacetin can influence TGF-β-induced EMT in GC cells. First, we investigated the influence of acacetin on the morphology of MKN45 and MGC803 cells. The results indicated that the morphological changes from epithelioid to mesenchymal in the TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml)-treated cells were reversed after the administration of acacetin, and monomer alone did not affect the appearance of the cells (Fig. 3A). Next, wound healing and Transwell migration assays were used to assess the effects of acacetin on TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml)-induced invasion and migration. Acacetin attenuated TGF-β1-activated migration of GC cells (p < 0.05, Fig. 3B). Cell migration to the chambers was inhibited (p < 0.05, Fig. 3C). Finally, in the TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml)-treated GC cells (p < 0.05, Fig. 3D), acacetin influenced protein expression, which was reflected in the suppression of mesenchymal biomarkers (N-cadherin, MMP-2 and Snail) and the enhancement of epithelial markers (E-cadherin). These results indicated that acacetin can reverse TGF-β1-activated EMT.

Fig. 3.

Effect of acacetin on invasion and migration in TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml)-treated MKN45 and MGC803 cells. A Morphological changes in MKN45 and MGC803 cells that were untreated or treated with acacetin. B Wound healing assays detected the effect of acacetin on TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml)-induced invasion of GC cells. C Transwell assays measured invasion and migration influenced by acacetin in GC cells under TGF-β1 treatment. D Western blot analysis of the protein changes in TGF-β1-induced EMT in GC cells. The quantitative values are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 3). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 compared to the control group. # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001 compared to the TGF-β1 alone group

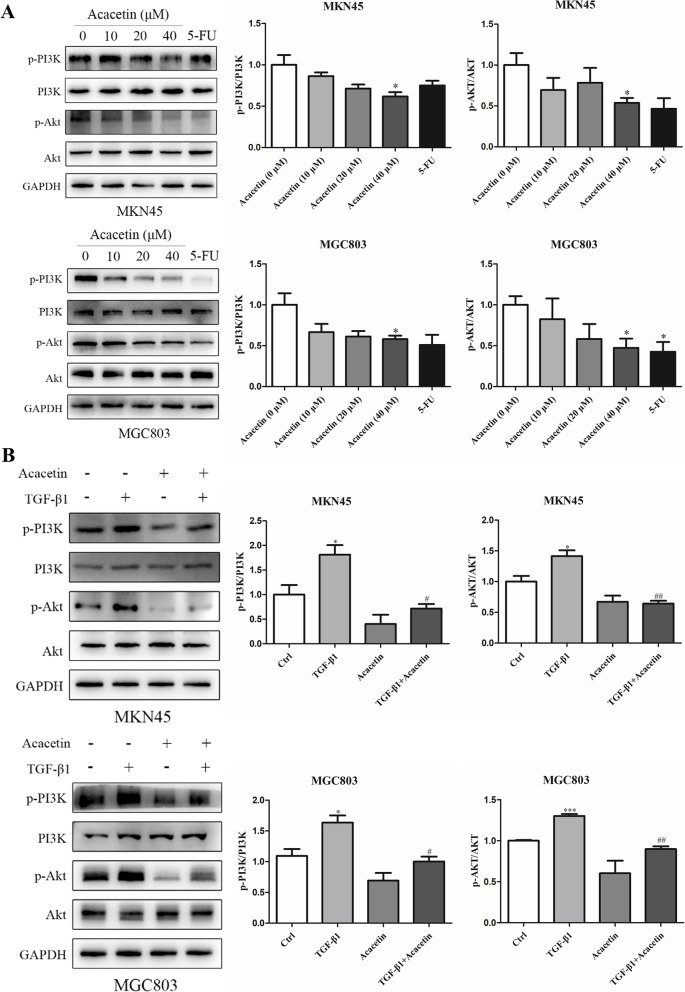

Acacetin reversed activation of the Akt pathway in MKN45 and MGC803 cells

PI3K/Akt regulates cell proliferation and migration through a variety of mechanisms [12]. To explore the potential molecular mechanism by which acacetin inhibits invasion and migration in GC cells, we examined the effect of acacetin on the PI3K/Akt pathway. As shown by the western blot results in Fig. 4A (p < 0.05), acacetin reduced the phosphorylation of PI3K and Akt in a dose-dependent manner. Previous studies have shown that TGF-β can activate the Akt pathway [31, 32]. Then, we analysed the effects of acacetin on the TGF-β-activated Akt pathway. As presented in Fig. 4B (p < 0.05), acacetin decreased the expression levels of p-PI3K and p-Akt, which were increased by TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml). These findings suggested that the PI3K/Akt signalling pathway may be the mechanism by which acacetin inhibits the metastasis of GC cells.

Fig. 4.

Effect of acacetin on the phosphorylation levels of PI3K and Akt in TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml)-treated GC cells. A Western blot analysis of the phosphorylation of PI3K and Akt in GC cells treated with acacetin. B GC cells were treated with TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml) in the absence or presence of acacetin. The quantitative values are expressed as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 compared to the control group. # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01 compared to the TGF-β1 alone group

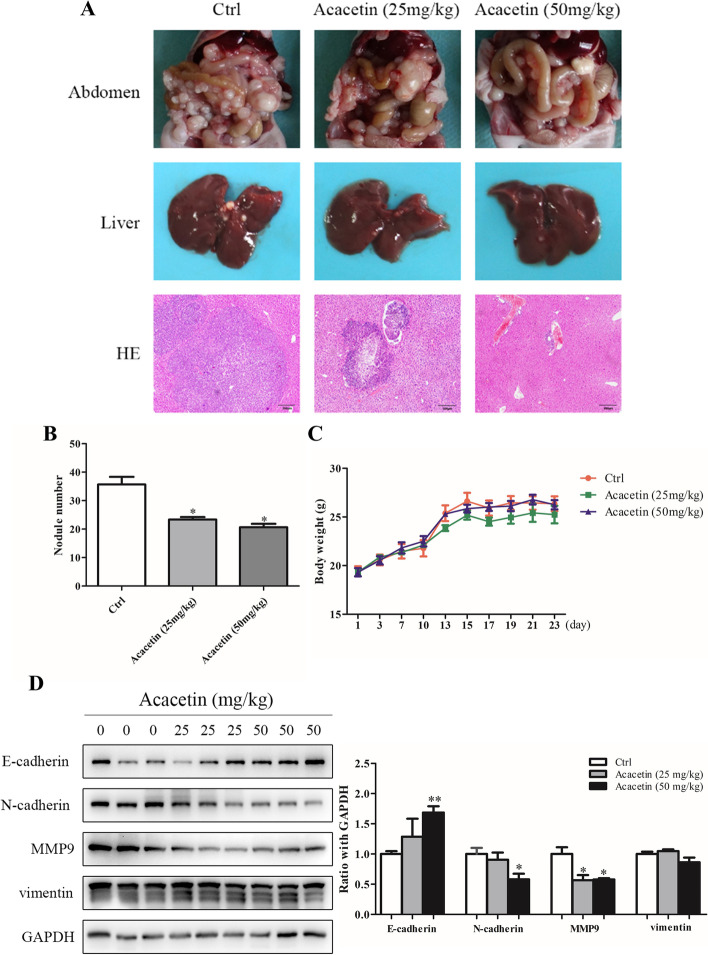

Effect of acacetin on peritoneal metastasis in vivo

To further determine the effects of acacetin in inhibiting GC metastasis, we established a peritoneal metastasis model in nude mice. The results showed more tumour nodules in the abdomen and metastatic tumour nodules in the livers of the mice in the acacetin low-dose and high-dose groups than those in the control groups (p < 0.05, Fig. 5A, B). Haematoxylin-eosin staining of the liver showed larger metastatic nodules in the control group, while only a small lump of neoplastic tissues adjacent to the blood vessels was found in the acacetin high-dose group (Fig. 5A). There was no significant difference in body weight among the groups (p < 0.05, Fig. 5C). Then, we detected the expression of EMT-related proteins using hepatic metastatic nodules. The western blot results indicated that the expression of N-cadherin and MMP-9 was decreased and that of E-cadherin was increased, whereas the expression of Vimentin in the acacetin groups did not change significantly compared with that in the control group (p < 0.05, Fig. 5D). These results indicated that acacetin can inhibit the metastasis of GC in vivo.

Fig. 5.

Mechanism of acacetin in peritoneal metastasis of GC in nude mice. A Tumours were implanted in the abdomen, and then, the gross and microscopic pathological features of metastatic nodules in the livers of mice were observed. B The number of cancerous nodules colonizing the abdomen. C Changes in body weight in nude mice. D Difference in EMT-related protein expression in liver metastatic nodules of mice treated with different concentrations of acacetin. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 3). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 compared to the control group

Discussion

The objective of this study was to investigate the effect of acacetin on TGF-β1-induced EMT in GC cells and explore its possible mechanism. In vitro experiments showed that acacetin inhibited the invasion and migration of GC cells by regulating EMT-associated proteins. This effect was further confirmed in TGF-β1-induced EMT models. Subsequent experiments proved that acacetin inhibited the phosphorylation of PI3K and Akt in MKN45 and MGC803 cells and then activated the PI3K/Akt pathway. Acacetin also reversed the phosphorylation of PI3K and Akt. In vivo experiments showed that acacetin inhibited the growth of peritoneal tumours. Further analyses showed that acacetin regulates EMT-related proteins in hepatic metastatic nodules and suppresses liver metastasis.

The mortality of GC is higher and the prognosis is poorer due to recurrent disease, even in patients with surgical resection. GC easily metastasizes to other parts of the body, and the peritoneum is the most common site of metastasis [4]. Therefore, inhibiting tumour metastasis can improve the survival of GC patients. EMT is a crucial biological process that facilitates cancer metastasis [33]. The present study found that acacetin inhibits the invasion and migration of GC cells. The effect confirmed by subsequent trials was achieved by altering the expression of EMT-related proteins. The results showed that acacetin downregulated the expression of N-cadherin and upregulated the expression of E-cadherin. Members of the MMP family, MMP2 and MMP9, play a key role in tumour invasion, metastasis and angiogenesis [34]. We also found that acacetin reduced the expression of MMP2 and MMP9 in MKN45 and MGC803 cells. This result suggested that the inhibitory effects of acacetin on GC metastasis were achieved by controlling the expression of MMPs. Snail, a critical transcriptional repressor of E-cadherin, plays an important role in oncogenesis and EMT [35]. Our research found that acacetin significantly suppressed the expression of Snail in GC cells.

In the TGF-β1-induced EMT models of MKN45 and MGC803 cells, acacetin reversed the morphology of mesenchymal-like spindle-shaped cells and reduced invasion and migration stimulated by TGF-β1. Additionally, acacetin attenuated the overexpression of the mesenchymal marker N-cadherin, the transcription factor Snail and MMP2 and MMP9, although acacetin promoted the expression of the epithelial marker E-cadherin, which was reduced by TGF-β1. These results indicated that in TGF-β1-treated GC cells, acacetin inhibited EMT and repressed invasion and migration.

TGF-β can activate a variety of signalling pathways, such as Smad, ERK, p38 MAPKs, PI3K and RAS [36]. The PI3K/Akt pathway plays a key role in TGF-β-induced EMT of GC cells, and the phosphorylation of PI3K and Akt is increased during the progression of GC [37, 38]. In this study, we first examined the effects of acacetin on different signalling pathways, such as p38 MAPKs, through western blotting. We found that acacetin suppressed the phosphorylation of PI3K and Akt. Then, in the activated PI3K pathway, acacetin abrogated the upregulation of p-PI3K and p-Akt expression. Collectively, these results suggested that acacetin may inhibit TGF-β1-induced EMT of GC cells by inhibiting the PI3K/Akt signalling pathway. The detailed molecular mechanism requires further study.

As previously mentioned, peritoneal metastasis is the most common type in GC, occurring in approximately 10–30% of newly diagnosed patients, and more than 50% of patients in stage II–III developed peritoneal metastasis within 5 years after radical resection [39]. We select MKN45 cell line for animal experiment due to MKN45 originate from lymph node metastasis in a patient with gastric signet-ring cell carcinoma with poorly cohesive. In this study, we found that acacetin prohibits the growth of tumours in the abdomen. Furthermore, 4–14% of new cases with GC have liver metastasis [40], resulting in poor prognosis due to the lack of effective treatment. We also found that acacetin inhibits liver metastasis of GC cells. This effect is associated with the suppression of EMT. These results demonstrated that acacetin can control the development of peritoneal metastasis and inhibit liver metastasis of GC.

Conclusions

In summary, our study showed that acacetin inhibits the migration, invasion and EMT of GC cells by suppressing the PI3K/Akt signalling pathway. Furthermore, we affirmed that acacetin inhibits the peritoneal metastasis and liver metastasis of GC. These results suggested that acacetin could be developed as a potential therapeutic agent for the treatment of metastatic disease of GC.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Institute of Traditional Chinese Medicine Oncology of Longhua Hospital affiliated with Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine for providing us with a superior research platform and learning environment.

Abbreviations

- EMT

Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

- TGF-β1

Transforming growth factor-β1

- GC

Gastric cancer

- CCK-8

Cell Counting Kit-8

- MMP

Matrix metalloproteinase

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- IC50

Half maximal inhibitory concentration

Authors’ contributions

Ai-Guang Zhao, Xiao-Hong Zhu, Yan Xu, and Ni-Da Cao designed and supervised the study. Guang-Tao Zhang, Zhao-Yan Li, Jia-Huan Dong, and Wei-Li Zhou performed experiments and were involved with data collection and analysis. Guang-Tao Zhang, Zhao-Yan Li, Zhan-Xia Zhang, and Zu-Jun Que. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by (1) the Ministry of Science and Technology National Key Research and Development Program (Grant No. 2017YFC1700605) and (2) the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82004133).

Availability of data and materials

The data associated with this study are included in this published article. Additional files are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals approved by Longhua Hospital, Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Approval number: LHERAW-2003). We carried out these experiments in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org).

Consent for publication

No applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Guangtao Zhang and Zhaoyan Li contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Cutsem E, Sagaert X, Topal B, Haustermans K, Prenen H. Gastric cancer. Lancet (London, England) 2016;388(10060):2654–2664. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30354-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoo CH, Noh SH, Shin DW, Choi SH, Min JS. Recurrence following curative resection for gastric carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2000;87(2):236–242. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sakamoto Y, Sano T, Shimada K, Esaki M, Saka M, Fukagawa T, Katai H, Kosuge T, Sasako M. Favorable indications for hepatectomy in patients with liver metastasis from gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2007;95(7):534–539. doi: 10.1002/jso.20739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nieto MA, Huang RY, Jackson RA, Thiery JP. EMT: 2016. Cell. 2016;166(1):21–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, Nieto MA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139(5):871–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dongre A, Weinberg RA. New insights into the mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and implications for cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20(2):69–84. doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hyun KA, Koo GB, Han H, Sohn J, Choi W, Kim SI, Jung HI, Kim YS. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition leads to loss of EpCAM and different physical properties in circulating tumor cells from metastatic breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7(17):24677–24687. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Timmerman LA, Grego-Bessa J, Raya A, Bertrán E, Pérez-Pomares JM, Díez J, Aranda S, Palomo S, McCormick F, Izpisúa-Belmonte JC, et al. Notch promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition during cardiac development and oncogenic transformation. Genes Dev. 2004;18(1):99–115. doi: 10.1101/gad.276304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernando RI, Castillo MD, Litzinger M, Hamilton DH, Palena C. IL-8 signaling plays a critical role in the epithelial-mesenchymal transition of human carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2011;71(15):5296–5306. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng JC, Leung PC. Type I collagen down-regulates E-cadherin expression by increasing PI3KCA in cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2011;304(2):107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kunita A, Baeriswyl V, Meda C, Cabuy E, Takeshita K, Giraudo E, Wicki A, Fukayama M, Christofori G. Inflammatory Cytokines Induce Podoplanin Expression at the Tumor Invasive Front. Am J Pathol. 2018;188(5):1276–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2018.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mihalko EP, Brown AC. Material Strategies for Modulating Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transitions. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2018;4(4):1149–1161. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.6b00751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yeh HW, Lee SS, Chang CY, Lang YD, Jou YS. A New Switch for TGFβ in Cancer. Cancer Res. 2019;79(15):3797–3805. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikushima H, Miyazono K. TGFbeta signalling: a complex web in cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(6):415–424. doi: 10.1038/nrc2853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu J, Lamouille S, Derynck R. TGF-beta-induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Cell Res. 2009;19(2):156–172. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Derynck R, Muthusamy BP, Saeteurn KY. Signaling pathway cooperation in TGF-β-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2014;31:56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piek E, Moustakas A, Kurisaki A, Heldin CH, ten Dijke P. TGF-(beta) type I receptor/ALK-5 and Smad proteins mediate epithelial to mesenchymal transdifferentiation in NMuMG breast epithelial cells. J Cell Sci. 1999;112(Pt 24):4557–4568. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.24.4557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramírez-Moya J, Wert-Lamas L, Santisteban P. MicroRNA-146b promotes PI3K/AKT pathway hyperactivation and thyroid cancer progression by targeting PTEN. Oncogene. 2018;37(25):3369–3383. doi: 10.1038/s41388-017-0088-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larue L, Bellacosa A. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in development and cancer: role of phosphatidylinositol 3′ kinase/AKT pathways. Oncogene. 2005;24(50):7443–7454. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu H, Wang YJ, Yang L, Zhou M, Jin MW, Xiao GS, Wang Y, Sun HY, Li GR. Synthesis of a highly water-soluble acacetin prodrug for treating experimental atrial fibrillation in beagle dogs. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25743. doi: 10.1038/srep25743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang W, Wu QQ, Xiao Y, Jiang XH, Yuan Y, Zeng XF, Tang QZ. Acacetin protects against cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction by mediating MAPK and PI3K/Akt signal pathway. J Pharmacol Sci. 2017;135(4):156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jphs.2017.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun LC, Zhang HB, Gu CD, Guo SD, Li G, Lian R, Yao Y, Zhang GQ. Protective effect of acacetin on sepsis-induced acute lung injury via its anti-inflammatory and antioxidative activity. Arch Pharm Res. 2018;41(12):1199–1210. doi: 10.1007/s12272-017-0991-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fong Y, Shen KH, Chiang TA, Shih YW. Acacetin inhibits TPA-induced MMP-2 and u-PA expressions of human lung cancer cells through inactivating JNK signaling pathway and reducing binding activities of NF-kappaB and AP-1. J Food Sci. 2010;75(1):H30–H38. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2009.01438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chien ST, Lin SS, Wang CK, Lee YB, Chen KS, Fong Y, Shih YW. Acacetin inhibits the invasion and migration of human non-small cell lung cancer A549 cells by suppressing the p38α MAPK signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biochem. 2011;350(1–2):135–148. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0692-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shen KH, Hung SH, Yin LT, Huang CS, Chao CH, Liu CL, Shih YW. Acacetin, a flavonoid, inhibits the invasion and migration of human prostate cancer DU145 cells via inactivation of the p38 MAPK signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biochem. 2010;333(1–2):279–291. doi: 10.1007/s11010-009-0229-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones AA, Gehler S. Acacetin and Pinostrobin Inhibit Malignant Breast Epithelial Cell Adhesion and Focal Adhesion Formation to Attenuate Cell Migration. Integr Cancer Ther. 2020;19:1534735420918945. doi: 10.1177/1534735420918945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liang CC, Park AY, Guan JL. In vitro scratch assay: a convenient and inexpensive method for analysis of cell migration in vitro. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(2):329–333. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Puisieux A, Brabletz T, Caramel J. Oncogenic roles of EMT-inducing transcription factors. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16(6):488–494. doi: 10.1038/ncb2976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Papageorgis P. TGFβ Signaling in Tumor Initiation, Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition, and Metastasis. J Oncol. 2015;2015:587193. doi: 10.1155/2015/587193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kato M, Putta S, Wang M, Yuan H, Lanting L, Nair I, Gunn A, Nakagawa Y, Shimano H, Todorov I, et al. TGF-beta activates Akt kinase through a microRNA-dependent amplifying circuit targeting PTEN. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11(7):881–889. doi: 10.1038/ncb1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baek SH, Ko JH, Lee JH, Kim C, Lee H, Nam D, Lee J, Lee SG, Yang WM, Um JY, et al. Ginkgolic Acid Inhibits Invasion and Migration and TGF-β-Induced EMT of Lung Cancer Cells Through PI3K/Akt/mTOR Inactivation. J Cell Physiol. 2017;232(2):346–354. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cao QH, Liu F, Li CZ, Liu N, Shu M, Lin Y, Ding L, Xue L. Testes-specific protease 50 (TSP50) promotes invasion and metastasis by inducing EMT in gastric cancer. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):94. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4000-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shay G, Lynch CC, Fingleton B. Moving targets: Emerging roles for MMPs in cancer progression and metastasis. Matrix Biol. 2015;44-46:200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2015.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skrzypek K, Majka M. Interplay among SNAIL Transcription Factor, MicroRNAs, Long Non-Coding RNAs, and Circular RNAs in the Regulation of Tumor Growth and Metastasis. Cancers. 2020;12(1):209. doi: 10.3390/cancers12010209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moustakas A, Heldin CH. Non-Smad TGF-beta signals. J Cell Sci. 2005;118(Pt 16):3573–3584. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu J, Zhang Y, Xu R, Du J, Hu Z, Yang L, Chen Y, Zhu Y, Gu L. PI3K/Akt-dependent phosphorylation of GSK3β and activation of RhoA regulate Wnt5a-induced gastric cancer cell migration. Cell Signal. 2013;25(2):447–456. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou H, Wu J, Wang T, Zhang X, Liu D. CXCL10/CXCR3 axis promotes the invasion of gastric cancer via PI3K/AKT pathway-dependent MMPs production. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;82:479–488. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.04.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yonemura Y, Endou Y, Shinbo M, Sasaki T, Hirano M, Mizumoto A, Matsuda T, Takao N, Ichinose M, Mizuno M, et al. Safety and efficacy of bidirectional chemotherapy for treatment of patients with peritoneal dissemination from gastric cancer: Selection for cytoreductive surgery. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100(4):311–316. doi: 10.1002/jso.21324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schlansky B, Sonnenberg A. Epidemiology of noncardia gastric adenocarcinoma in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(11):1978–1985. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data associated with this study are included in this published article. Additional files are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.