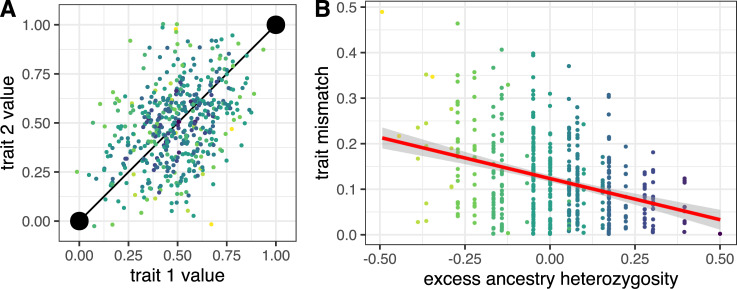

Fig 1. Results from simulations illustrating how an ecological mechanism could underlie the heterozygosity–incompatibility relationship in F2 hybrids.

Both panels depict results from a representative simulation run of adaptive divergence and hybridization between 2 populations. We consider an organism with 2 traits that have both diverged as a result of selection. Colored points are individual hybrids, with darker colors indicating higher heterozygosity. Panel (A) depicts the distribution of 500 F2 hybrid phenotypes in two-dimensional trait space. Large black points are the 2 parent phenotypes, which are connected by a black line indicating the “axis of divergence.” Panel (B) depicts the relationship between individual excess ancestry heterozygosity and trait “mismatch” of individual hybrids [13]. Excess ancestry heterozygosity is the observed heterozygosity minus the expected heterozygosity based on ancestry proportion—0 is the expected mean in the absence of selection (approximately observed heterozygosity frequency of 0.5). Mismatch is calculated as the shortest (i.e., perpendicular) distance between a hybrid’s phenotype and the black line connecting parents in (A). Variation parallel to this axis connecting parents in (A) captures variation in the “hybrid index.” The plot shows that trait mismatch is lower in more heterozygous F2 hybrids. Heterozygosity values are discrete because a small number of loci underlie adaptation in the plotted simulation run. Simulations are outlined in the Methods. The “mismatch”–heterozygosity relationship is stronger, although less intuitive, in organisms with greater dimensionality (i.e., more traits; see S1 Fig for a case with 10 traits following [18]). The data and code required to recreate this figure may be found at https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.h18931zn3.