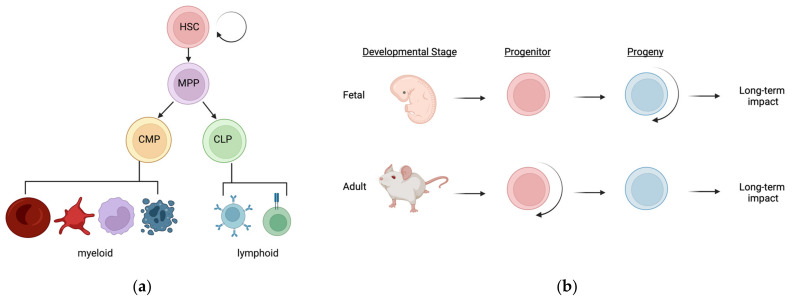

Figure 1.

The hematopoietic hierarchy and sources of potential long-term impacts following nicotine exposure: (a) Hematopoiesis is the process of generating all mature blood and immune cells from hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). This process occurs in a well-defined hierarchy during adult steady-state hematopoiesis, as depicted in this simplified tree structure. HSCs differentiate into multipotent progenitors, and then either common myeloid progenitors (CMPs) or common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs), before terminally differentiating into mature blood and immune cells of either myeloid or lymphoid classification. HSCs are unique in their ability to both self-renew as well as differentiate into all of these progenitors and mature cells; (b) During fetal hematopoiesis, distinct waves of hematopoietic stem and progenitors (HSPCs) exist throughout development and adulthood. Many of the progenitors that exist during early fetal development are non-self-renewing but can give rise to self-renewing progeny such as “non-traditional” tissue-resident immune cells. Subsequently and during adult steady-state, hematopoiesis is sustained by self-renewing progenitors (HSCs) that give rise to non-self-renewing, short-lived progeny such as “traditional” circulating RBCs and WBCs. Nicotine exposure may influence life-long immunity by two potential mechanisms: (1) nicotine causes changes or persistence in HSPCs which results in altered hematopoietic output for life, or (2) nicotine causes a change in the long-lived immune cells during their establishment which alters immunity later in life. These mechanisms are not mutually exclusive and a combination of both could lead to altered hematopoiesis and altered immunity for life. Adapted from Cool and Forsberg, 2019 [20].