Abstract

Cancer treatment faces the challenge of selective delivery of the cytotoxic drug to the desired site of action to minimize undesired side effects. The liposomal formulation containing targeting ligand conjugated cytotoxic drug can be an effective approach to specifically deliver chemotherapeutic drugs to cancer cells that overexpress a particular cell surface receptor. This research focuses on the in vitro and in vivo studies of a peptidomimetic ligand attached doxorubicin for the HER2 positive lung and breast cancer cells transported by a pH-dependent liposomal formulation system for the enhancement of targeted anticancer treatment. The selected pH-sensitive liposome formulation showed effective pH-dependent delivery of peptidomimetic-doxorubicin conjugate at lower pH conditions mimicking tumor microenvironment (pH-6.5) compared to normal physiological conditions (pH 7.4), leading to the improvement of cell uptake. In vivo results revealed the site-specific delivery of the formulation and enhanced antitumor activity with reduced toxicity compared to the free doxorubicin (Free Dox). The results suggested that the targeting ligand conjugated cytotoxic drug with the pH-sensitive liposomal formulation is a promising approach to chemotherapy.

Keywords: pH-sensitive liposome, Doxorubicin, peptide conjugate, lung cancer, HER2

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Cancer is the second leading cause of death and is responsible for nearly 10 million deaths in 2020 [1]. Lung and breast cancers are two of the leading causes of cancer death in the US, and an estimated about 45% of deaths in males and females due to lung cancer and 15% of deaths in females for breast cancer in the year 2020 [2]. Among the lung cancers, approximately 85% are histologically classified as non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). The members of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) family of proteins are known to be overexpressed in different types of cancers such as breast, lung, ovarian, and colon [3]. The receptor family consists of four members: human epidermal growth factor receptor-1 (HER1) or EGFR and HER2–4. HER2 is known to be overexpressed/altered in 30% of breast cancer and 4–25% of lung cancer[4–6]. Spontaneous dimerization of HER2 occurs via gene amplification or kinase activation by EGFR or HER3 [7]. Heterodimerization can happen by ligand binding to EGFR or HER3 extracellular domain (ECD), which triggers a change in the conformation of the proteins leading to cell signaling. It was found that the HER2 gene is amplified in 15–20% of breast cancer patients, which is associated with aggressive disease behavior[8,9]. Studies also revealed that HER2 overexpression was a marker of poor prognosis in lung cancer [10].

The major drawbacks of chemotherapeutic anticancer drugs are the nonspecificity towards cancer cells and poor water solubility [11–13]. Cancer chemotherapy faces the challenge of delivering the drug into the tumor sites in a specific manner [14,15]. The non-selective nature of chemotherapeutic drugs leads to increased toxicity to normal cells causing serious side effects [16,17]. Doxorubicin (Dox) is a well-known and highly potent anthracycline class antibiotic used for the treatment of different types of cancers such as lung, colon, breast cancer, and leukemia [18,19]. Dox lacks tumor-specificity due to its activity against all dividing cells, and, in cases of higher doses, Dox treatment can cause irreversible cardiotoxicity [20]. Other limitations of Dox treatment include the development of resistance due to a decrease in membrane permeability, mutation of target proteins, and enhancement of efflux pumping [21–23]. Therefore, the development of bioavailable and cancer cell-specific anticancer drugs is extremely important for the treatment of cancer. However, the discovery of a novel anti-cancer molecule requires an extensive research program backed by huge financial support. Thus, nowadays, researchers in academia and pharma companies are trying to modify existing potent anticancer drugs for improvement of specificity towards cancer cells, solubility, and efficacy [13,24,25]. Different approaches were evaluated to improve Dox selectivity and anticancer activity through conjugating Dox with tumor-specific agents that bind to overexpressed cell surface receptors on the tumor cells. Previously, we have conjugated Dox with peptidomimetic compound 5 (5-Dox) that has selectivity toward HER2-overexpressed cancer cells. Peptidomimetic compound 5 binds to the extracellular domain IV of HER2 and inhibits HER2 dimerization with other EGFRs [26]. 5-Dox conjugate showed higher specificity towards the HER2-overexpressed cancer cell lines, although it lacks the desired serum stability for better drug efficacy [27].

Nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems are being broadly evaluated for the site-specific delivery of anticancer drugs and enhancement of therapeutic efficacy [28–34]. Polyethylene Glycol (PEGylated) liposomes, in particular, possess the stealth property with extended circulation half-life and preferentially accumulate to the tumor site mediated by the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect reported both in the experimental research and in the clinic [35–39]. For the enhancement of the efficacy of the anticancer drug, targeted ligand conjugated cytotoxic molecule attached in the outer layer of nanocarrier giving additional sophistication in selectivity can be a novel approach for targeted drug delivery technique. Moreover, recent advances have given more attention to stimuli-responsive nanoparticles to reach tumor microenvironments (TMEs) [40]. pH-sensitive liposomes (PSLs) are an effective stimuli-responsive approach that can efficiently increase drug accumulation in the TME even in resistant cells [41]. The micro-environment of tumors is developed with tumor cells and new tumor vascularity along with acidosis (pH 5.5–6.9) [42–44]. Therefore, pH-sensitive liposomes have the potential to deliver the drugs toward tumor sites at the TME [44–46]. The PSLs can be formulated by incorporating pH-sensitive lipids, fatty acids, pH-sensitive polymer, pH-sensitive peptides [47]. Long circulating PSLs are the most common, which usually consists of DOPE (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine), CHEMS (cholesteryl hemisuccinate), and PEGylated lipid [47]. Additionally, the effect of PEG content on PSL was also reported by Duan et al. and found that PEG in PSL retained excellent pH sensitivity in addition to maintaining long blood circulation, suitable for in vivo application [48].

In this work, a pH-sensitive liposomal formulation containing peptidomimetic-doxorubicin conjugate (PS5-DoxL) (Figure 1) was constructed and anticipated to have a dual function of the liposomal formulation that it could release the conjugate specifically to the TME and the conjugate subsequently can bind specifically HER2 receptors rendering cell growth inhibition as well as targeted delivery of Dox. Moreover, the engulfment of the liposome could also release Dox inside of the cancer cell, inhibiting cell growth. On the other hand, pH-sensitive liposomes (PS5-DoxL) can also increase drug accumulation and ligand attachment increasing the drug specificity towards HER2 positive lung (Calu-3) and breast (BT474) cancer cell lines. The PS5-DoxL has targeting properties, while 5-Dox conjugate efficiently inhibits the growth of cancer, specifically HER2 positive cancer cell lines. The pH-sensitive release properties, stability, cancer cell death profiles, specificity of PS5-DoxL towards HER2 positive cancer cells were carried out in HER2 positive as well as cell lines that express the basal level of the HER2 protein. In vitro two-dimensional (2D) cellular and three-dimensional (3D) tumor spheroidal drug accumulation in respect of pH-sensitivity profile, the antitumor activity of the liposomes were evaluated in spheroids to demonstrate the effectiveness of PS5-DoxL as a possible targeted therapeutic agent for HER2 positive cancer. Additionally, In vivo biodistribution evaluation showed effective accumulation of the liposome formulation to the targeted site with increased efficacy and reduced toxicity compared to free Dox.

Figure 1.

The schematic diagram for preparation and proposed cancer cell targeting mechanism of PS5-DoxL.

Materials and methods

Materials

Dioleoylphosphatidylethanolamine (DOPE), Cholesteryl Hemisuccinate (CHEMS) were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Cholesterol (CHOL) was obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), and 1,2-Distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (methoxy(polyethylene glycol)-2000) (DSPE-PEG) was bought from Laysan Bio, Inc. (AL, USA). Dox was obtained from AstaTech (Bristol, PA). Cell Titer-Glo® and CellTiter-Glo® 3D Cell Viability Assay reagents were purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). Propidium iodide (PI) flow cytometry kit was obtained from abcam (Cambridge, UK), Annexin V − FITC + PI apoptosis detection kit purchased from Leinco Technologies, inc. (St. Louis, MO). Pooled Normal Human Serum was purchased from Innovative Research (MI, USA), Amicon Ultra 30kDa filter centrifuge tubes were purchased from EMD-Millipore (Billerica, MA), 96-well hanging drop plates for 3D spheroids formation were obtained from 3D Biomatrix (Ann Arbor, MI), and Spectrum™ Spectra/Por™ 1 RC Dialysis Membrane Tubing 6000–8000 Dalton MWCO was also purchased from Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). DiR iodide (1,1-dioctadecyl-3,3,3,3-tetramethylindotricarbocyanine iodide) was purchased from AAT Bioquest, Inc. CA, USA.

Cells and animals

All cell lines studied were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Cell lines Calu-3 and A549 were cultured with Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium (EMEM) and Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 medium (RPMI-1640) accordingly. Human HER2 positive breast cancer cell line BT474 and HER2 negative MCF-7 were cultured using RPMI-1640 medium. Non-cancerous human lung fibroblast cells (HLFs) were cultured in Fibroblast Basal Medium. The complete media was prepared by adding 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 1% insulin with basal media. All the cells were maintained in an incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2. BALB/c nude mice were purchased from Harlan (ENVIGO) Laboratories, IN, USA. All animal studies were conducted according to the University guidelines in addition to the approved protocol by the Institutional Animal Care and User Committee (IACUC) committee, University of Louisiana Monroe, and National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines.

Compound 5 synthesis with glutaric anhydride linker

Compound 5 was synthesized by the solid-phase synthesis method, as reported previously [26,27,49]. Briefly, the synthesis was done in a polypropylene frit using Fmoc-Phe-Wang resin (128 mg, 0.39 mmol/g) fitted column. After all the steps of washing and Fmoc deprotection, a small amount of resin was utilized to obtain the peptide from the resin and subsequently analyzed with HPLC and mass spectrometry. Molecular formula, C33H40N6O7, calculated monoisotopic mass, 632.295, experimental m/z [M+H]+ 633.337.

Dox-compound 5 conjugate

Dox-compound 5 conjugate (5-Dox) was synthesized according to the procedure reported in our previous paper [27]. Dox was conjugated to compound 5 through a glutaric anhydride linker. The conjugate was analyzed by HPLC and mass spectroscopy. The molecular formula is C60H67N7O17; calculated monoisotopic mass, 1157.459; experimental m/z [M+H]+ 1158.495.

Standard Curve of 5-Dox Concentration

5-Dox dissolved in PBS, and the fluorescence intensities of 5-Dox solutions were determined at an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and an emission wavelength of 590 nm in Biotek® plate reader (Winooski, VT, USA). The standard curve of 5-Dox was measured with serial dilation: 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 1, 3, and 5 μM. The standard curve of 5-Dox concentration with R2 of about 0.9867 was measured (Figure S1).

Formulation optimization of pH-sensitive 5-Dox liposomes

Four different 5-Dox containing pH-sensitive liposomal formulations (Table 1) were prepared using the thin-film hydration method followed by extrusion as described previously [50–52]. A known amount of lipids and 5-Dox were placed in a round bottom flask and dissolved in 1 ml of chloroform: methanol (9:1, v/v) mixture according to the prescribed amount indicated in Table 1. Then the solvent was evaporated, and the film formed on the flask wall was then flushed with nitrogen gas for 30 min and stored 2 hours in a desiccator to remove any traces of chloroform. The dried film was hydrated with phosphate buffer saline (PBS) and sonicated at 53 °C for 30 min using a bath sonicator. Then, the liposome suspension was extruded 7 times with a pore size of 100 nm through a polycarbonate membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). Resultant liposomes were subjected to ultracentrifugation (Amicon Ultra 30kDa filter) to remove free 5-Dox. The final concentrated liposome solution was collected and stored at 4 °C until further use. Depending on the drug release profile best four formulations were evaluated in terms of in vitro pH-dependent release profile in pH 6.5 and pH 7.4.

Table 1.

Composition of four different liposomal formulations.

| Amount required (mmol/ml) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Components | Formulation-1 | Formulation-2 | Formulation-3 | Formulation-4 |

| DOPE | 5.8 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 5.8 |

| CHEMS | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.7 |

| CHOL | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | - |

| DSPE-PEG | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| 5-Dox | 0.43 | 0.86 | 1.29 | 0.86 |

| Lipid: 5-Dox ratio | 32: 1 | 16: 1 | 10.7: 1 | 11.3: 1 |

Preparation of Liposomes

The selected 5-Dox loaded pH-sensitive liposome formulation (PS5-DoxL) was prepared as described by the previous method [50–52]. Briefly, DOPE, CHEMS, CHOL, DSPE-PEG, and compound 5-Dox in 5.7: 3.8: 4.0: 0.25: 0.86 molar ratio were taken in a round bottom flask and dissolved in chloroform: methanol (9:1, v/v) mixture. The compound to lipid molar ratio was 16:1. Then the solvent was evaporated, hydrated with PBS, and sonicated. The extrusion and removal of the free 5-Dox were done in the same way as described in the materials and methods section above. The pH-sensitive Free Dox liposome (PS-DoxL) was prepared using the same lipid composition with Free Dox instead of 5-Dox. The non-pH-sensitive 5-Dox liposome (NPS5-DoxL) was prepared using DPPC, CHOL, DSPE-PEG, and compound 5-Dox in a 5.45: 5.17: 0.25: 0.86 molar ratio.

Physicochemical Characterization of Liposomes

The particle size, polydispersity index (PDI), and zeta potential of the liposomes were measured using a NanoBrook 900Plus PALS (Brookhaven Instruments Corporation, NY, USA) at 25°C. The liposomes were appropriately diluted with distilled and filtered water (0.2 μm pore size) before the measurements. All measurements were done in triplicate.

Encapsulation efficiency

Encapsulation efficiency was measured by the previously described method [51]. The liposome solution of filtered and unfiltered liposomes was disrupted with 10% Triton X-100 (v/v), and 5-Dox concentration was measured by spectrofluorometer (excitation/emission – 485/590 nm). The encapsulation efficiency of 5-Dox was estimated from the following formula:

Morphology of liposomes

The morphological analysis of liposomes was carried out by transmission electron microscopy (JEOL JEM-1400) at Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, using a negative staining method. For morphological observation, 3 μl sample liposomes solution were dropped on the glow discharged 300 mesh carbon filmed grid (CF300-CU-50, EMS) and used a wick filter paper to remove excess liquid. Finally, the sample was stained with 2% uric acid for morphological evaluation. Cryogenic transmission electron microscopy (Cryo-TEM) imaging was done using a 4 μl sample solution applied to a glow discharged 300 mesh carbon-coated TEM grid (EMS CF300-cu). The blotting procedure and the quenching of specimens were performed with a cryoplunge 3 (Gatan, UK). After cold stage transfer, the samples were mounted and examined in TEM, operating at an accelerating voltage of 120kv. The stage temperature was kept below −170°F, and images were recorded at defocus setting with Gatan US1000xp2 camera.

In Vitro Drug Release

The drug release study was done according to the previously described method [44]. The required amount of different liposomal solutions was taken into a dialysis bag (cut-off M.W. 6,000–8,000). 1 mL of PS5-DoxL, NPS5-DoxL, PS-DoxL, and Free Dox solution (Dox-sol) were placed into the dialysis bag separately. Then the dialysis bags were inserted into 40 mL PBS with 0.5% Tween-80 (200 μL) at different pHs (pH 6.5 or pH 7.4), and the released systems were gently shaken at 140 rpm at 37 °C. The sample was taken at different time points and measured by the spectrofluorometer (excitation/emission – 485/590) for 5-Dox release.

Stability of liposome

In vitro stability of PS5-DoxL was examined at 4 °C storage conditions for 90 days and in human serum for 72 hours. PS5-DoxL was kept in 4 °C storage condition, and particle size and 5-Dox concentration were evaluated at different time point up to 90 days. Serum stability was evaluated according to the previously described method [53]. Briefly, human serum was centrifuged, and the supernatant was filtered with a 1 μm syringe filter to remove any suspended particles. The sample was taken at 0, 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 hours to measure particle size and 5-Dox concentration. For HPLC analysis of 5-Dox, 100 μL of the liposomal formulation was dissolved in methanol and filtered through a 0.2 μm filter before analyzing in the HPLC. The HPLC analysis was done according to our previously reported method [27].

Antiproliferative activity study

The antiproliferative effects of Free Dox, 5-Dox, and PS5-DoxL against Calu-3, BT474, A549, MCF-7, and non-cancerous lung fibroblast cells (HLFs) were determined by CellTiter-Glo® assay[54]. Calu-3 and A549 are HER2 positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines, where BT474 is HER2 positive breast cancer cell line. MCF-7 is HER2 negative (does not overexpress HER2) breast cancer cell. BT474, A549, MCF-7 cells were cultured in RPMI1640, Calu-3 were cultured in EMEM media, and HLFs in Fibroblast Basal Medium. Cells were coated on 96-well plates and incubated for 24 h (37 °C, 5% CO2). The cells were then treated with different concentrations of compounds and liposomes (0.001 μM–100 μM). After 72-h incubation, cells were washed with PBS, and the CellTiter-Glo® detection reagent was added. Finally, luminescence measurements were performed using a Biotek® plate reader (Winooski, VT, USA). All experiments were carried out in triplicate. A dose-response plot was generated, and the IC50 value was calculated.

In vitro cellular uptake assay by spectrofluorometer

A cellular uptake study was done according to a previously described method [55]. For quantitative cellular uptake analysis, Calu-3 and BT474 cells at 5 × 105/well were seeded and incubated for 24 h in an incubator at 37 °C under an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 90% relative humidity. When the cells reached 80% confluence, PS5-DoxL was added (at a 5-Dox concentration of 3 μM) and incubated for 1, 2, 4, and 6 hours at pH 7.4 and pH 6.5, respectively. At each time point, the treatment solution was then discarded, and the cells were washed three times with PBS. Finally, the cells were dissolved in 0.5% Triton X-100 solution for cell lysis. After 5 min incubation under gentle shaking, the fluorescence intensities were measured with a Biotek® plate reader (excitation/emission – 485/590 nm). Cellular uptake efficiency was expressed as the percentage of cells-associated fluorescence after washing versus the fluorescence present in the feed suspension.

In vitro cellular uptake by fluorescence microscopy analysis

For the fluorescence microscopy study, Calu-3 and BT474 cells were seeded in 8 well microscopic slides and cultured for 24 hours. Then the medium was removed and replaced with PS5-DoxL formulations (3 μM) in pH 7.4 and pH 6.5, and the cells were incubated for 30 min to 4 hours. After incubation, cells were washed with PBS and then fixed by adding 500 μL of ice-cold methanol and incubating the slides at −20 °C for 15 minutes. The methanol was discarded, and immediately 500 μL of PBS was added twice for washing to the wells and to prevent cell dehydration. Finally, cells were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), and mounted on slides with a coverslip. Slides were visualized using an Olympus BX63 fluorescence microscope. As a control, HER2 negative MCF-7 cells treated with PS5-DoxL for 4 hours and BT474 cells treated with NPS5-DoxL (3 μM), 4 hours were also carried out in the abovementioned procedure.

Cell cycle analysis

Calu-3 and BT474 cells (2×105 cells/mL) were seeded in 25 ml flasks and cultured overnight. Then the media was removed, and the flasks were treated with Free Dox (3 μM), 5-Dox (3 μM), PS5-DoxL (3 μM), and for control left untreated for 12 hours with drug and serum-free media. Subsequently, the cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 66% ethanol in water for 2 hours at +4 °C. After centrifugation at 25,000 rpm, rehydrated the cells with ice-chilled PBS and washed twice with PBS. Finally, cells were rehydrated with 9.45 mL PBS and stained with 500 μL of propidium iodide and 50 μL of RNase and incubated for 30 minutes before running the samples in a flow cytometer. The cells were analyzed for DNA content (10,000 events) using a fluorescence-activated cell-sorting (FACS) Calibur instrument.

Apoptosis study

Flow cytometric analysis of the cellular death pathway was evaluated [13]. Calu-3 and BT474 cells in 2×105 cells/mL were seeded in 25 ml flasks and cultured for 24 hours. At 70% cell confluency, the media was replaced with a treatment solution of Free Dox (3 μM), 5-Dox (3 μM), PS5-DoxL (3 μM), Plain PSL (3 μM), and serum-free media and incubated for 12 hours. After incubation, the cells were trypsinized and washed with ice-cold PBS. Cells were re-suspended in binding buffer with a cell volume of 2.5×106 cells/mL concentration. The cells suspensions were transferred to flow cytometry analysis tubes, and 10 μL of annexin V-FITC and 5 μL of propidium iodide were added. Then incubated for 15 minutes and performed flow cytometry analysis of the samples.

Western blot analysis

Calu-3 cells were treated with PS5-DoxL (3 μM), 5-Dox (3 μM), lapatinib (positive control at 1μM), and, without treatment, as a negative control. Cell lysates were collected after 36 hours prepared with cell lysis buffer. Bradford assay was carried out to determine the protein concentration in each of the sample lysates. Sample loading and antibody treatments were done according to the reported method [56]. Incubation for imaging was carried out with peroxide substrate and enhancer solutions from a Super Signal™ West Femto chemiluminescence kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). ChemiDoc™ Touch Imaging System from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA) was employed to expose the membrane and obtain images. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a control.

Antiproliferative and antitumor activity in multicellular three-dimensional (3D) tumor spheroid

Hanging drop plates were used to grow multicellular 3D tumor spheroid (MCTS). Calu-3, BT474 and, MCF-7 cells in 40 μL of medium (500 cells/μL concentration) were dispensed into hanging drop plate wells through the access holes. The spheroids were formed in 24 hours through incubation at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and in a humidified atmosphere. After spheroid formation confirmation, a round-bottom 96-well plate was used to receive the spheroids transferred from the hanging drop plates by adding 100 μL of serum-free media. Then, the spheroids were treated with different concentrations (0.01 to 100 μM) of PS5-DoxL, 5-Dox, and Free Dox. After treatment, the 96 round-bottom well plates were incubated for 72 hours in the incubator at 37 °C. Finally, a CellTiter-Glo® 3D cell viability assay was done, and a plate reader was used for luminescence detection. The IC50 values were obtained according to our previously reported method [27]. Multicellular 3D tumor spheroid growth of cell lines Calu-3 and BT474 were also carried out in the hanging drop method [13,27]. The 3D cellular experiments have the potential to mimic tumors in certain aspects, therefore, can be utilized as a preliminary evaluation before in vivo studies [57–59]. In brief, 40 μL of medium containing about Calu-3 in 250 cells/μL, BT474 and, MCF-7 in 125 cells/μL concentration were dispensed into the access holes of the hanging drop plate wells. The tumor spheroids were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and in a humidified atmosphere for the days till the size of the spheroid reached up to around 100–200 μm. After the confirmation of the spheroid formations with a confocal microscope, the spheroids in the medium were transferred to round-bottom 96-well plates by placing the hanging drop plates on top of the plates. Later, the spheroids morphologies were evaluated with EVOS® FL Cell Imaging System microscopy under 4 × objectives, and it was mentioned as day zero. Then, the spheroids were divided into four groups and treated with PS5-DoxL (3 μM), 5-Dox (3 μM), Free Dox (3 μM) and left untreated as a control. The size of the spheroids was imaged by the EVOS® FL Cell Imaging System for five days continually. Images were analyzed by ImageJ software (National Institute of Health), and tumor spheroid volumes were calculated using the following formula-

Fluorescence microscopy analysis of multicellular 3D tumor spheroid

For fluorescence microscopic analysis of the multicellular 3D tumor spheroid, Calu-3, BT474, and MCF-7 (HER2 negative) cell spheroids were grown. Calu-3 cells were coated in 250 cells/μL concentration, and BT474 and MCF-7 cells were coated 125 cells/μL concentration. 40 μL of medium were dispensed into the access holes of the hanging drop plate wells. After 72 hours, the spheroids were transferred into 8 well microscopic slides and treated with PS5-DoxL (3μM) in pH 7.4 and pH 6.5 up to 4 h. Untreated spheroids were also kept as control. Tumor spheroids were washed with cold PBS followed by fixation with methanol. Finally, cells were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), and mounted on slides with a coverslip. Slides were visualized using an Olympus BX63 fluorescence microscope under 4X and 10X objectives.

In vivo imaging and biodistribution analysis

To create the Calu-3 tumor-bearing mouse model, Calu-3 cells (1 × 107 cells) were resuspended in 100 μL culture media and subcutaneously injected into the right-back of male and female BALB/c nude mice (22–35 g). The fluorescent dye 1,1′-Dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′ tetramethylindotricarbocyanine iodide (DiR) was used to replace 5-Dox in the formulation [60]. Tumor-bearing nude mice were randomly separated into two groups (n = 3) and intravenously injected with free DiR and PSL-DiR at a dosage of 200 μg kg−1 of DiR, respectively, when the tumor volume reached around 100–150 mm3. The mice were anesthetized and photographed using in vivo imaging equipment (IVIS® Lumina, PerkinElmer, USA) at 3, 8, and 24 hours after injection. The mice were killed after 24 h post-injection, and the major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney), as well as tumors, were taken for ex vivo imaging (IVIS® Lumina, PerkinElmer, USA).

Another biodistribution study was conducted with the same procedure and injected with Free Dox, PS5-DoxL, and NPS5-DoxL at a dosage of 600 mg kg−1 of Dox [61]. The mice were killed after 24 h post-injection, and the major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney), as well as tumors, were taken for ex vivo imaging (IVIS® Lumina, PerkinElmer, USA).

In vivo antitumor activity

Calu-3 cells (1 × 107 cells) were resuspended in 100 μL culture media and subcutaneously injected into the right-back of male and female BALB/c nude mice (22–35 g) as described above. When the tumor volume reached around 30–50 mm3, Calu - 3 bearing nude mice were randomly assigned to five groups (n = 5) and intravenously administered PBS (control), free Dox, 5-Dox (treated peptide 5 conjugated with doxorubicin HCl), Plain LP (treated with plain liposome without any drug), NPS5-DoxL (treated with non-pH-sensitive liposome containing Dox-peptide conjugate) PS5-DoxL (treated with pH-sensitive liposome containing Dox-peptide conjugate) at a Dox-equivalent dose of 6 mg kg−1 every four days, respectively. Tumor volume and body weight in the Calu- 3 -bearing nude mice were also measured every four days. At the conclusion of the experiment, the nude mice were sacrificed, and the final tumor weights were evaluated to determine the anticancer activity. The major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney), as well as tumors, were extracted after the mice were killed at 38 days. The volume of the tumor was calculated as follows: V (mm3) = L × W2/2, where, L and W represent the major and minor axes of the tumor, respectively.

Histopathology studies

Tumors from each group were removed and fixed in buffered 10% formalin. After fixation, the tissue was embedded in a paraffin block. Five-micron sections were prepared, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) following routine histology laboratory procedures. The morphologic analysis was conducted by an experienced pathologist.

Toxicity study

The body weight loss of the mice was recorded during the antitumor activity in vivo. All animals were killed after the anti-tumor effectiveness study was completed, and major organs were evaluated for toxicity. Tissues of organs treated in formalin were embedded in paraffin blocks and cut into 5 μm sections. Hematoxylin and eosin were used to stain micro sections of the lung tumor, heart, kidney, liver, and spleen (H&E) and examined microscopically by an experienced toxicologist.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data in all sections were presented as the mean ± SD, and statistical evaluations were performed to assess significance among groups. The P-value less than 0.05, 0.01, or 0.001 was considered statistically significant to be highly significant. For in vivo studies, mixed effect statistical models with both fixed and random effects with repeated measures were used to estimate the least squares means (LS-means) of change in tumor volume. Treatment, Time, and Treatment by Time interaction were included in the model. The correlation between time points of the same subject was considered, and a compound symmetric covariance structure was used. The pairwise comparisons of response variables between control and treatments and Plain LP and treatments at each time point after day 10 were reported. The conservative Tukey’s adjustment was used in the post hoc analysis to account for the testing of multiple hypotheses.

Results

Liposome formulation selection

The design strategy for the 5-Dox conjugate incorporated pH-sensitive liposome (PS5-DoxL) formulation is postulated in Figure 1. The aim is to formulate optimum pH-sensitive 5-Dox conjugated liposomal formulation for HER2 targeted anticancer treatment through a site-specific drug delivery approach. Based on the existing literature, we started our formulation with a composition of DOPE:CHEMS:CHOL:DSPE-PEG:5-Dox at different ratios (Table 1). The 5-Dox release was monitored at pH 6.5 and 7.4 with these formulations (Figure S2). Among the formulations evaluated for release of 5-Dox, Formulation-2 had a significantly higher release of 5-Dox at pH 6.5 compared to 7.4 (Figure S2), and within five hours, nearly 60% of 5-Dox was released, and this formulation was named PS5-DoxL (Figure S2 B).

Characteristics of PS5-DoxL

The particle size of PS5-DoxL was 170.34 ± 3.75 nm with a polydispersity index (PDI) of 0.209 ± 0.016. The zeta potential of PS5-DoxL was - 24.57 ± 4.68, and the entrapment efficiency of 5-Dox in PS5-DoxL was 88.45 ± 1.50 (Table 2 and Figure 2A–D). Other control liposomes free-Dox in a pH-sensitive liposome (PS-DoxL) and non-pH-sensitive peptidomimetic 5-Dox conjugate liposome (NPS5-DoxL), pH-sensitive liposome without Dox-conjugate or Dox (plain PSL) characteristics are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The characterization of PS5-DoxL, PS-DoxL and, NPS5-DoxL (n=3)

| Liposomes | Diameter (nm) | PDI | Zeta-potential (mV) | Entrapment Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS5-DoxL | 170.34 ± 3.75 | 0.209 ± 0.016 | −24.57 ± 4.68 | 88.45 ± 1.50 |

| PS-DoxL | 155.57 ± 3.62 | 0.220 ± 0.013 | −6.91 ± 1.23 | 88.94 ± 0.48 |

| NPS5-DoxL | 155.52 ± 4.01 | 0.281 ± 0.009 | −15.73 ± 0.50 | 92.32 ± 1.98 |

| Plain PSL | 135.33 ± 1.78 | 0.169 ± 0.019 | −28.81 ± 1.59 | - |

Figure 2.

(A) Particle Size distribution and (B) Zeta Potential graphs of PS5-DoxL (C) TEM and (D) cryo-TEM images showing the morphological characteristics of PS5-DoxL at different magnifications. E) In vitro release of 5-Dox or Free Dox from PS5-DoxL, NPS5-DoxL, and PS DoxL at 37 °C, pH 6.5 and 7.4 PBS buffer medium, respectively. Data represent the mean ± SD (n=3). Statistical significance between PS5-DoxL 7.4 and PS5-DoxL 6.5 (** p <0 .01 and *** p <0 .001)

In vitro drug release profile of liposomes

The in vitro release of 5-Dox from PS5-DoxL and NPS5-DoxL or Free Dox from PS5-DoxL in both pH 6.5 and 7.4 buffer solutions was investigated. As shown in Figure 2 E, the released 5-Dox from PS5-DoxL was significantly higher at pH 6.5 compared to 7.4 starting from 1 h and maintained the release difference up to 24 h. The 5-Dox release reached around 64% within 6 hours at pH 6.5, whereas it was 48% at pH 7.4. The Free Dox release from PS-DoxL formulation was also high in pH 6.5 compared to pH 7.4 although, there was no difference in the release of 5-Dox from NPS5-DoxL in both buffer solutions.

Long term and serum stability of liposome

In the 4° C storage condition, the particle size showed slight changes until 60 days, indicating stable formulation but increased significantly in 90 days compared to the initial particle size (Figure 3A). The 5-Dox concentration was also more than 90% up to 60 days and dropped to around 80% in 90 days (Figure 3B). In human serum, the particle size remains almost constant up to 72 h, indicating no aggregation of particles in human serum (Figure 3C). In human serum, 5-Dox concentration in PS5-DoxL was 86 % in 24 h but later decreased to 46% in 72 h (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Stability data of (A) PS5-DoxL long term stability stored at 4° C up to 90 days analyzed in particle size analyzer, (B) 5-Dox in PS5-DoxL stored at 4° C up to 90 days analyzed by HPLC, (C) PS5-DoxL in human serum up to 72 h, and D. 5-Dox in PS5-DoxL in human serum up to 72 h analyzed by HPLC.

Note: 0 h relative Peak Area was considered 100%, and peak area at different time points was plotted with respect to 100%. Data represent the mean ± SD (n=3) and *** p <0 .001.

Antiproliferative activity

Two HER2 positive lung cancer cell lines Calu-3 and A549, and one breast cancer cell line, BT474, were used to evaluate the selective antiproliferative effect of PS5-DoxL. MCF-7 cells that do not overexpress HER2 and noncancerous human lung fibroblast cells (HLFs) were used as controls. The results indicated that PS5-DoxL showed antiproliferative activity in the nanomolar range in HER2-overexpressed cancer cell lines such as Calu-3, A549, and BT474; however, the IC50 values in MCF-7 and HLFs were many times higher (Table 3 and Figure S3). The conjugate 5-Dox also showed similar antiproliferative activity with comparatively less selectivity as it showed higher activity against MCF-7 and HLFs cell lines. However, free Dox showed similar antiproliferative action towards all the cell lines.

Table 3.

Antiproliferative activity of PS5-DoxL, 5-Dox, and Free Dox in Calu-3, A549, BT474, MCF-7, and HLFs

| IC50 in μM (72 Hours) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | Calu-3 | A549 | BT474 | MCF-7 | HLFs |

| PS5-DoxL | 0.540 ± 0.029 | 0.780 ± 0.032 | 0.617 ± 0.168 | 5.424 ± 1.957 | >50 |

| 5-Dox | 0.532 ± 0.082 | 0.484 ± 0.138 | 0.633 ± 0.147 | 3.841 ± 0.205 | 5.447 ± 0.081 |

| Free Dox | 0.158 ± 0.075 | 0.490 ± 0.079 | 0.399 ± 0.079 | 0.316 ± 0.165 | 0.170 ± 0.082 |

| Plain PSL | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

In-vitro pH-Dependent cellular uptake assay by a spectrofluorometer

To assess the ability of pH-sensitive release of PS5-DoxL, the cellular uptake of 5-Dox was quantitatively evaluated up to 6 h in pH 7.4 and pH 6.5 by incubating Calu-3 and BT474 cell lines under these pH conditions. The drug uptake was significantly higher in pH 6.5 compared to pH 7.4 starting from 1 h of treatment in both of the cell lines (Figures 4 A and 4 B).

Figure 4.

In vitro cellular uptake analysis by spectrofluorometer up to 6 h in (A) Calu-3 and (B) BT474 cell lines treated with PS5-DoxL in pH 7.4 and pH 6.5.

Notes: Data represent the mean ± SD (n=3). Statistical significance between pH 7.4 and pH 6.5 (* p <0.05, ** p <0.01, and *** p <0 .001)

In-vitro pH-Dependent fluorescence microscopy analysis

Drug uptake was investigated in Calu-3 and BT474 cell lines from 30 min to 4 hours in pH 7.4 and pH 6.5 treated with 3 μM of PS5-DoxL, and images were captured in different time points to visualize the pH-dependent uptake. The concentration of Dox for cellular imaging was optimized using 1 and 3 μM concentration of PS5-DoxL in BT474 cells (Figure S4). Figure 5 shows the fluorescence microscopic images of A) Calu-3 and B) BT474 cells treated with PS5-DoxL (3 μM). The nuclei were observed by staining with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), while the distribution of Dox and the PS5-DoxL was studied by the autofluorescence of the Dox. Figures 5A and B show that in both of the cell lines, Dox was internalized and accumulated in the nucleus within 30 min of treatment. Dox fluorescence was significantly higher in pH 6.5 incubated cells compared to pH 7.4 incubated cells. The fluorescence in the Calu-3 cells incubated with PS5-DoxL at pH 6.5 showed strong Dox fluorescence in both the nucleus and cytoplasm from 30 min to 4 h, whereas fluorescence in the cells treated with PS5-DoxL in pH 7.4 was less in the cytoplasm and the nucleus (Figure 5A). In Figure 5B, we observed the fluorescence in BT474 cells treated with PS5-DoxL at pH 6.5 revealed strong Dox fluorescence in the cytoplasm and the nucleus beginning from 30 min and remained until 4 h although fluorescence in the cells treated with PS5-DoxL in pH 7.4 showed less intensity in the cytoplasm and the nucleus in the same time intervals. A similar study was carried out on MCF-7 cells to evaluate the specificity of the PS5-DoxL. Fluorescence microscopic images (Figure S5A) reveal that in the MCF-7 cells incubated with PS5-DoxL at pH 7.4 and 6.5, there was no Dox fluorescence in MCF-7 cells during 4 h of incubation. The NPS5-DoxL formulation in BT474 cells was used as a control in both of the pH conditions and found no significant difference in Dox fluorescence between pH 7.4 and pH 6.5 treated cells (Figure S5B).

Figure 5.

Time-dependent uptake of PS5-doxL in (A) Calu-3 and (B) BT474 cells in pH 7.4 and pH 6.5 for 30 min, 1, 2, and 4 h. Scale bar corresponds to 10 μm (60 × magnification).

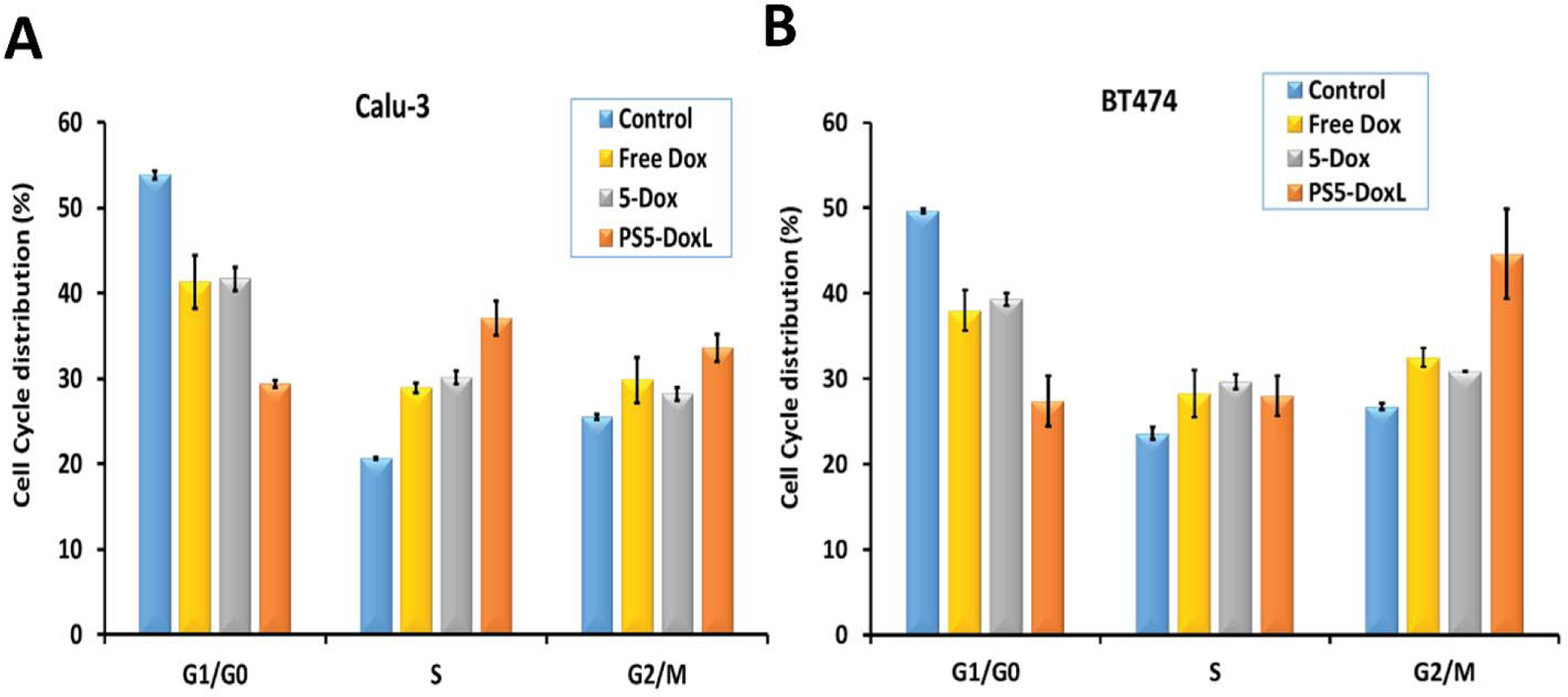

Cell cycle analysis

Calu-3 and BT474 cell lines were treated with PS5-DoxL, 5-Dox conjugate, Free Dox, and control (without treatment) for 12 h; then, after fixation with ethanol overnight, the samples were analyzed using a flow cytometer (Figure S6). In Calu-3 cells (Figure 6A), the distribution pattern of cells in PS5-DoxL treated cells was increased in the S phase and G2/M phase compared to the untreated cell sample. Free Dox and 5-Dox treated samples also showed a similar increase, but the cell cycle inhibition was greater in PS5-DoxL treated cell samples. In the BT474 cell (Figure 6 B), similar cell distribution patterns were found where PS5-DoxL treated cells were increased in the S phase and G2/M phase compared to the untreated cell sample. In Free Dox and 5-Dox treated cells, the S phase was increased almost the same as PS5-DoxL treated cell sample, but G2/M phase arrest was greater in the PS5-DoxL treated cells.

Figure 6.

Effect of 5-Dox and PS5-DoxL on cell cycle arrest in HER2-overexpressed cancer cells (A) Calu-3 and (B) BT474. Data represented as mean ± standard deviation.

Apoptosis Assessment

The induction of apoptosis in Calu-3 and BT474 cells is shown in (Figure S7). The total percentage of apoptosis in Calu-3 cells was found to be 22.90 %, 10.12 %, 16.83 %, 2.72 %, and 2.51 % for PS5-DoxL, 5-Dox, Free Dox, Plain PSL, and control (Figure 7A). The total percentage of apoptosis in BT474 was similar such as 26.66 %, 22.37 %, 35.49 %, 6.97 %, and 1.14 % for PS5-DoxL, 5-Dox, Free Dox, Plain PSL, and control (Figure 7B). Analyzing the apoptosis study data, we found that the percentage of the apoptotic cells was significantly greater in 5-Dox and PS5-DoxL treated cells compared to control in both cell lines.

Figure 7.

The proportion of apoptosis in (A) Calu-3 and (B) BT474 after treatment Plain PSL, Free Dox, 5-Dox, and PS5-DoxL or left untreated as a control for 12 h. Statistically significant (p <0.001) differences is shown as (***) with Control (n=3).

Western Blot Analysis

To analyze the PS5-DoxL effect in the binding and inhibition of HER2 protein and subsequent contribution in intracellular signaling, a Western blot study was done on Calu-3 cells, which overexpress the HER2 protein. Calu-3 was incubated with 5-Dox and PS5-DoxL, and after extraction of HER2 protein, Western blot analysis was done to determine the amount of phosphorylated protein (Figure S8). Measurement of HER2 phosphorylation protein was done by p-HER2 monoclonal antibody. Quantitative analysis of Western blot revealed a significant reduction of the phosphorylation of HER2 kinase by PS5-DoxL treatment compared to control (without treatment). A positive control, Lapatinib [62], was used, which is an EGFR and HER2 kinase dual inhibitor. The results suggest that 5-Dox was substantially released from PS5-DoxL in the tumor microenvironment and binding of 5-Dox to the ECD (HER2 extracellular domain) inhibited the phosphorylation of the intracellular kinase domain of HER2 (Figure S8A). Furthermore, phosphorylation of Akt was evaluated to find whether PS5-DoxL can inhibit any down-stream signaling molecules (Figure S8B).

Antiproliferative activity on multicellular three-dimensional tumor spheroid (3D-MCTS)

The hanging drop method was used to create spheroids in various cell lines, which is beneficial because it is simple and repeatable; additionally, these spheroids imitate tissue rather than other scaffold-based methods such as extracellular matrix (ECM) scaffolds and hydrogel systems [63]. The IC50 values were calculated through dose-response curve analysis for different treatments (Table 4 and Figure S9) and found that PS5-DoxL, 5-Dox, and Free Dox inhibited the 3D spheroids with IC50 values of 0.660 ± 0.140, 0.687 ± 0.148, and 0.745 ± 0.054 in Calu-3 respectively. In BT474 the IC50 values were 0.728 ± 0.123, 0.755 ± 0.024, and 0.845 ± 0.058 and in MCF-7 IC50 values were 3.602 ± 0.137, 5.157 ± 0.215, and 0.548 ± 0.125 for PS5-DoxL, 5-Dox, and Free Dox respectively.

Table 4.

Antiproliferative activity in multicellular 3D tumor spheroids of Calu-3, BT474, and MCF-7 treated with PS5-DoxL, 5-Dox, and Free Dox.

| 3D tumor spheroid IC50 in μM (72 Hours) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | Calu-3 | BT474 | MCF-7 |

| PS5-DoxL | 0.660 ± 0.140*# | 0.728 ± 0.123* | 3.602 ± 0.137 |

| 5-Dox | 0.687 ± 0.148 | 0.755 ± 0.024 | 5.157 ± 0.215 |

| Free Dox | 0.745 ± 0.054 | 0.845 ± 0.058 | 0.548 ± 0.125 |

Notes: Data represent the mean ± SD (n=3).

statistical significance between PS5-DoxL and Free Dox;

statistical significance between PS5-DoxL and 5-Dox (* and # p <0.05)

In vitro tumor growth inhibition study in 3D lung and breast tumor spheroids

The tumor spheroids were divided into 4 different treatment groups and treated with PS5-DoxL, 5-Dox and, Free Dox at 3 μM concentration or left untreated as a control for 5 days. Tumor spheroids were regularly imaged from 1 to 5 days using an EVOS® cell imaging system (Figures S10 & 11). In Calu-3 and BT474 spheroids, significant inhibition of tumor growth in day 5 was found in PS5-DoxL treatment compared to control and Free Dox treated groups. The 5-Dox treatment caused significant inhibition compared to control, and Free Dox treated groups in Calu-3 spheroids (Figure 8 and Figure S11A) and only against control in BT474 spheroids (Figure 9 and Figure S11B). In both HER2 positive lung and breast cancer cell spheroids, PS5-DoxL treatment caused more pronounced inhibition of tumor spheroidal growth compared to other groups. In contrast, MCF-7 (HER2 negative tumor cell) spheroids showed significant inhibition of spheroidal tumor growth only with the treatment of Free Dox (Figures S10 and S11C). Figures S11ABC show the tumor-spheroid morphology changes after different treatments.

Figure 8.

(A) Morphological images and (B) quantitative graph for inhibition of spheroid growth of Calu-3. Scale bars correspond to 1000 μm. Data presented as mean±SD (n=5). **p<0.01 compared with control, and #p<0.05 compared with Free Dox.

Figure 9.

(A) Morphological images and (B) quantitative graph for inhibition of spheroid growth of BT474. Scale bars correspond to 1000 μm. Data presented as mean±SD (n=5). **p<0.01 compared with control, and ###p<0.001 compared with Free Dox.

Fluorescence microscopy analysis of multicellular 3D tumor spheroid

In this study, the drug uptake was evaluated in pH 7.4 and pH 6.5 conditions treated with PS5-DoxL or without treatment as a control in Calu-3, BT474 (HER2 positive), and MCF-7 (HER2 negative) multicellular 3D tumor spheroid by confocal microscope (Figure S12, Figure 10 and Figure S13). The 3D tumor spheroids treated with PS5-DoxL showed higher Dox fluorescence in pH 6.5 condition compared with pH 7.4 treated condition indicating the higher drug release and uptake in lower pH condition. The Dox fluorescence was found widespread as well as in the core of the spheroids in 4 h, indicating higher drug uptake in pH 6.5 condition due to facilitated drug release in addition to liposomal uptake. In contrast, the 3D tumor spheroids of MCF-7 showed no Dox fluorescence in any of the pH conditions (Figure S13).

Figure 10.

BT474 3D-MCTS treated with PS5-DoxL for 4 h in pH 7.4, pH 6.5, or without treatment as control.

In vivo imaging and biodistribution analysis

The biodistribution results showed that PS5-DoxL could increase cell uptake and enhance the Dox accumulation in HER2 positive Calu-3 cells. To label the liposomes in this experiment, the fluorescent probe DiR was used instead of the Dox to facilitate in vivo imaging. As shown in Figure 11, the fluorescence signals of free DiR were found in major organs, but throughout the next 24 hours, there was almost no fluorescence at the tumor site. However, the fluorescent signals accumulated in tumors in the PSL-DiR group at 1 hour after injection (highlighted in red circle), and the signal strength increased greater at 24 hours after injection. Because the stimuli sensitive property and physicochemical characteristics suitable for the tumor microenvironment showed that PSL-DiR could significantly increase tumor targeting and DiR accumulation. Additionally, from 3 to 24 hours, the Free DiR group demonstrated rapid elimination. The liposome-treated group, on the other hand, had a longer stay in the body and greater accumulation in the tumor site. PSL-DiR could also target the tumor via an enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, according to imaging of excised tissues and tumors. A histogram of fluorescence intensity also revealed that the drug accumulation in normal organs, such as the lung (Figure 11C), was lower than in the Free DiR group, demonstrating that the liposomes did not generate toxic drug reactions or substantial side effects.

Figure 11.

(A) After intravenous injection of Free DiR and PSL-DiR at 3, 8, and 24 hours, in vivo imaging of Calu-3 bearing nude mice. A red circle has been drawn around the tumors in the image (A). (B) 24 hours after injection, ex vivo fluorescence pictures of main organs and tumors. (C) Ex vivo major organs and tumors DiR fluorescence intensity at 24 hours after injection. ***p<0.001 compared to Free DiR.

Another biodistribution study was conducted with the same procedure treating with Free Dox, NPS5-DoxL, and PS5-DoxL and evaluated ex vivo after 24 h because Dox fluorescence can only be observed after the animal sacrifice and organs collection. The results showed that Dox fluorescence in the tumor was significantly higher in PS5-DoxL treated group compared to Free Dox and NPS5-DoxL treated groups (Figure S14). Ex vivo fluorescence imaging of major organs and tumors also revealed that The Dox fluorescence intensity of PS5-DoxL at tumor sites was significantly higher than that of other groups, demonstrating the potency of the pH-sensitive release of PS5-DoxL in improving cellular uptake and the EPR effect to improve Dox accumulation and retention at the tumor site.

In vivo anti-tumor study

In a tumor growth inhibition study, the therapeutic efficacy of PS5-DoxL was determined in vivo. As shown in Figure 12A, the tumor growth was significantly inhibited in the PS5-DoxL treatment group compared to the PBS treated (control) groups, Plain LP and NPS5-DoxL (p < 0.001). On day 22, PS5-DoxL was significantly lower than the control group, and on day 34, PS5-DoxL was significantly lower than the plain LP group. Moreover, PS5-DoxL significantly inhibited the growth of Calu-3 tumors compared with that in the 5-Dox treatment group (p < 0.01) and Free Dox treatment group (p < 0.05). The mean tumor size at 38 days after implantation in the PS5-DoxL, Free Dox and NPS5-DoxL was 28.60 ± 11.76, 68.26 ± 25.89 and 171.43 ± 31.18 mm3, respectively, compared with 352.67 ± 31.74 mm3 in the control group. The mean tumor weight was significantly inhibited as well at 38 days after implantation in the PS5-DoxL treated group (p < 0.001), weighing 82.60 ± 9.71 mg compared to 162.8 ± 21.98 and 345.36 ± 31.49 mg in Free Dox and control groups, respectively (Figure 12B and Figure S15). H&E stained images of the tumor tissues are shown in Figure 12D. All the tumor tissue revealed moderate to poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with an invasive growth pattern. Different levels of tumor necrosis were observed in all the Dox-treated groups, but in particular, PS5-DoxL treated group showed more extensive multi-foci necrosis with debris in the dilated glandular lumina.

Figure 12.

(A) Tumor volume and B) Tumor weight of mice from xenograft. (C) Body weight of Calu-3-bearing nude mice after various treatments. (D) images of tumor tissues (H&E staining). Scale bars represent 200 μm.

Notes: Data represent the mean ± SD (n=5). Statistical significance between different groups ($ or * p <0.05, ** p <0.01, and $ $ $ or ### or *** p <0 .001). $ showing comparison with control group and # showing comparison with Plain LP.

Toxicity study

The mice in the group treated with each of the liposomal systems or 5-Dox did not lose any weight, but the animals in the group treated with Free Dox faced significant weight loss in 38 days after tumor implantation compared to control (p < 0.01) and PS5-DoxL treated groups (p < 0.05) respectively (Figure 12C). H&E stained images of the primary organs are shown in Figure S16. In our histopathological study of the heart tissues, some amount of vascular degeneration was observed with Free Dox treated group compared to the control group; however, 5-Dox exhibited significant pathological abnormalities and a small number of eosinophilic myocytes and vacuolation and focal myofibril degeneration. NPS5-DoxL group showed hemorrhage and adjacent cardiomyocyte degradation. However, Plain LP and PS5-DoxL showed minimal pathology, indicating fewer side effects among the groups with some focal eosinic myocytes compared to control groups in the heart. In the spleen, Free Dox treated group showed loss of lymphoid blue matter and deposition of red matter. In contrast, 5-Dox treated group showed extramedullary hematopoiesis (EMH) megakaryocyte or macrophage, loss of lymphoid blue matter, and deposition of red matter compared with the control group. Moreover, NPS5-DoxL showed loss of white matter with gain in red pulp. However, PS5-DoxL treated group showed the least toxicity in the spleen compared with the control with a small reduction in lymphoid white matter. In the liver and kidneys of mice treated with Free Dox, 5-Dox, and different liposomes, no apparent inflammatory reaction, structural modification, or pathological abnormalities were found compared to the control group (treated with PBS), indicating minimal side effects on these organs (Figure S16).

Discussion

Nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems are being broadly evaluated for the site-specific delivery of anticancer drugs and enhancement of therapeutic efficacy [29,30,32,34]. PEGylated liposomes, in particular, possess the stealth property with extended circulation half-life in vivo and preferentially accumulate to the tumor site mediated by the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect reported both in the experimental research and in the clinic [35,37,38]. The micro-environment of tumors is developed with tumor cells and new tumor vascularity along with acidosis (pH 5.5–6.9) [42–44]. Therefore, pH-sensitive liposomes have the potential to deliver the drugs toward tumor sites at the TME [44–46]. Additionally, the effect of PEG content on PSL was also reported by Duan et al. and found that PEG in PSL kept excellent pH sensitivity in addition to maintaining long blood circulation, suitable for in vivo application as well [48].

Reduction of systemic toxicity of anticancer agents, application of drug delivery system for anticancer therapy has been a strategy widely researched [39,64]. In the universe of different nanostructures, the liposomes have been extensively researched, and site-specific and specialized resealed profiles (such as pH-sensitive liposomes) are the main strategies for targeted liposomal drug delivery [47,65]. Previous studies reported a successful pH-sensitive release profile of liposomes based on DOPE and CHEMS lipid combination carrying Free Dox [47,51,66]. We also followed a similar strategy for the pH-sensitive formulation; however, we had to optimize our formulation to evaluate the pH-sensitive release profile containing peptide doxorubicin (5-Dox) conjugate. Additionally, we assessed our formulation by adding cholesterol to achieve the better physicochemical property of liposomes [65].

In this study, we analyzed four different liposomal formulations of HER2 targeted ligand Dox conjugate using different ratios of components of a pH-sensitive liposome. Among the four formulations, formulation-2 had an initial onset of drug release at pH 6.5, reaching around 45 % within 2 h, and maintained significantly higher drug release compared to pH 7.0. Hence, formulation-2 was chosen for further study, and this formulation was named PS5-DoxL (Figure 2 E and Figure S2 B).

The PS5-DoxL formulation showed optimum size for accumulation into the tumor microenvironment [17], with PDI 0.20 indicating homogeneity of particles. Zeta potential also indicates a stable dispersion of particles with less undesirable interaction with other serum proteins. TEM and cryo-TEM analysis revealed the particle morphology, including the size and shape of the particles (Figure 2 C and 2 D). The PS5-DoxL particles showed a circular shape with a mean particle size around 170.34 nm. The particles had a homogenous phospholipid layer, as indicated in Cryo-TEM images. In-vitro release study indicated the pH-dependent higher release of the 5-Dox in an acidic environment. Thus, the formulation PS5-DoxL can efficiently release 5-Dox in the tumor microenvironment, which may contribute to better selectivity and efficacy as an anticancer agent. Particle size plays a major role in the in vivo drug delivery systems, in particular the delivery of drugs to lung tissue. If the particle size of nanomedicine is around 200 nm or less, they are retained in the lung tissue for a longer period and, hence, release more of the drug from the liposome [67]. If the liposomal particle has a hydrodynamic diameter > 200 nm, irrespective of whether the liposomes are coated with polymers (stealth component) or not, it exhibits a faster rate of intravascular clearance (splenic and hepatic sequestration) [68]. Thus, our liposomal formulation will remain in the tissue for a longer time in tissue.

Storing liposome formulations can lead to aggregation or leakage of drugs, and this can lead to variation in concentration of encapsulated drugs and degradation of drugs under certain conditions. To demonstrate the stability of PS5-DoxL in 4° C storage condition and human serum, particle size and 5-Dox concentration in PS5-DoxL were evaluated in HPLC at different time points. The aggregation sizes of the liposome formulation are an important factor for liposome stability. The activity of liposomes in vivo is also governed by the aggregation tendency of the liposome formulation.[69]. The human serum can represent the physiological conditions, and the aggregation potential of the liposome can be evaluated through particle size measurement.[70]. Stability data showed that PS5-DoxL liposomal formulation with stable 5-Dox in 4 ° C storage condition up to 90 days as well as in human serum where until 24 h with more than 80% of 5-Dox was stable in PS5-DoxL liposomal formulation. However, particle size increased significantly in 90 days compared to the initial size indicating some aggregation of liposome resulting in increased particle size. Furthermore, antiproliferative activity results showed better selectivity of PS5-DoxL in HER2-overexpressed cancer cell lines compared to cancer cells that do not overexpress HER2 protein (MCF-7) and noncancerous human lung fibroblast cells (HLFs).

Cellular uptake evaluation shows an indication of the drug uptake properties by the cells in a particular condition. Dox uptake was increased in pH 6.5 in 2 h, 4h, and 6 h compared to pH 7.4, maintaining significantly higher drug uptake at each time point. The higher cellular uptake measured by Dox fluorescence indicated the higher release of 5-Dox from PS5-DoxL in acidic conditions compared to normal pH conditions and subsequent uptake by the cells. The intracellular accumulation and distribution of PS5-DoxL in Calu-3 and BT474 were also evaluated using fluorescence microscopic analysis by measuring Dox fluorescence. The PS5-DoxL was found to show pH-dependent release noticeable from 30 min in both HER2 positive lung and breast cancer cell lines and maintained higher uptake of 5-Dox in a lower pH environment which was evaluated through the Dox fluorescence (Figure 5). The absence of Dox fluorescence in MCF-7 cells during 4 h of incubation indicated the specificity of PS5-DoxL towards HER2 positive cells congruent to the cytotoxic study. The NPS5-DoxL formulation could not show a difference in drug uptake in pH 7.4 and pH 6.5, suggesting the absence of the pH-dependent drug release profile in a low pH environment. These microscopic study results are congruent to the in vitro cellular uptake assay measured by Dox fluorescence that the acidic condition facilitated the release of 5-Dox from the carrier PS5-DoxL and higher uptake by the cells compared to normal pH condition.

Cell cycle inhibition is a well-known effect of Dox [71], and results showed a high amount of G2/M + S phase arrested cells after treatment with PS5-DoxL compared to the Free Dox and 5-Dox (Figure 6A and 6B and Figure S7) in different cell lines. The cell cycle analysis data supports the antiproliferative effects indicating PS5-DoxL effects on higher cellular toxicity against HER2 positive cell lines. Dox initiation of apoptotic cell death of cancer cells is well-known. Apoptosis studies (Figure 7 and Figure S7) indicated that the percentage of apoptotic cell death was enhanced in PS5-DoxL than the 5-Dox alone.

As indicated in the introduction, the conjugate we have formulated in the liposomal formulation has a dual function. Peptidomimetic binds to HER2 protein on cancer cells and inhibits EGFR:HER2 and HER2:HER3 dimerization, and this leads to inhibition of intracellular phosphorylation kinase activity and hence cell growth. In our previous studies, we have reported that compound 5 exhibits antiproliferative activity with IC50 values of 0.396, 0.895, and 0.601 μM in SKBR-3, BT-474, and Calu-3 cell lines that overexpress HER2 protein and 16.9 μM in MCF-7 cell lines that does not overexpress HER2 [26,27,72]. From Table 3, it is evident that PS5-DoxL exhibited comparable IC50 values in Calu-3 cell lines (0.660 μM). Since Dox and compound, 5 mechanism of action is different, it is very difficult to attribute IC50 value to a particular part of the 5-Dox conjugate and liposomal formulation. Compound 5 binds to HER2 on the cell surface and exerts its action on EGFR dimerization, whereas, Dox targets DNA. In Western blot analysis, findings indicate that 5-Dox was released in substantial quantities from PS5-DoxL in the tumor microenvironment and that binding of 5-Dox to the ECD (HER2 extracellular domain) prevented phosphorylation of HER2’s intracellular kinase domain. However, total HER2 protein levels were unchanged (Figure S8 A) in the different treatment groups. Moreover, the quantification of Western blot suggested that PS5-DoxL significantly inhibited the phosphorylation of Akt compared to control, and total Akt was unchanged in different treatment groups (Figure S8 B).

In two-dimensional (2D) culture systems, cells lack the native tumor characteristics because of their growth in a monolayer on a flat surface and lacking cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions. On the contrary, physiologically relevant cell-cell and cell-matrix interaction, signaling pathway profiles, gene expression, and in vivo tumors-related heterogeneity and structural complexity can be found in cancer cells propagated in three-dimensional (3D) culture systems [73]. As 3D cell-based experiments mimic tumors in many aspects and hence PS5-DoxL was evaluated in 3D tumor spheroids of Calu-3, BT474, and MCF-7 to understand the liposome activity and selectivity towards HER2 positive cancer. We found a significant reduction in the IC50 values of PS5-DoxL in the Calu-3 compared to the 5-Dox and Free Dox and in BT474 were compared to the Free Dox, indicating the higher activity of the liposomal PS5-DoxL formulation in multicellular 3D spheroid tumor tissue. The IC50 values were higher in 3D environments than in the 2D plates, which may be due to the differential effects in tissue penetrability of the compounds in the inner layer of cells in the spheroids. Previous reports also suggest higher IC50 values in 3D antiproliferative assay compared to 2D antiproliferative assay [73–75]. The results suggested higher efficacy of PS5-DoxL compared to Free Dox indicating the enhancement of the activity through the targeted effect of ligand, including the pH-responsive release of compound facilitating the drug uptake. The higher IC50 values in MCF-7 suggest the selectivity of the PS5-DoxL towards the HER2 positive cell line (Table 4 and Figure S9). Antitumor results in 3D-MCTS were congruent to the antiproliferative activity of PS5-DoxL, 5-Dox, and Free Dox in tumor spheroids (Figures 8 & 9, and Figure S10). The results suggested that the PS5-DoxL had greater antitumor activity against the HER2 positive tumor spheroids compared to Free Dox and parent 5-Dox conjugate and selectively active against the HER2 positive tumor cell lines (Figures 8 & 9, and Figure S10).

For in vitro model of drug penetration studies, it has been suggested that 3D spheroids are suitable compared to two-dimensional (2D) cell cultures [73,76]. The fluorescence microscopy data on 3D-MCTS indicate that the PS5-DoxL is acting more efficaciously in pH 6.5, improving drug uptake inside the tumor, and the 5-Dox conjugate is acting selectively to deliver the drug in HER2 positive breast and lung cancer cells (Figures 10 &S12). The drug uptake result is congruent with the 3D tumor spheroid antiproliferative and antitumor effect data, bolstering the results that the PS5-DoxL is more selectively efficacious in the HER2 positive tumor environment than HER2 negative tumor environment (Figure S13). Fluorescence microscopy analysis on 3D-MCTS suggested a promising stimuli-responsive formulation containing doxorubicin-peptidomimetic conjugate for selective and efficacious treatment targeting HER2 positive cancers with minimizing off-target toxicity.

The in vivo distribution and accumulation of liposomes after intravenous injections were next studied using the Calu-3 bearing nude mice model. The PS5-DoxL group showed the smallest tumor volume and weights (Figure 11AB and Figure S15) and greater drug accumulation (Figure 11 and Figure S14) compared to other treatment groups, including free Dox, suggesting the strongest tumor growth inhibition effect. These results can indicate that pH-sensitive property along with the conjugated peptide for HER2 targeting effect, which has the potency to minimize HER2 activity along with the efficient Dox release to the selected tumor environment causing significant tumor inhibition. The plain liposomes (Plain LP) seem to show some effect on tumor volume at the early days of tumor growth in mice (Figure 12A). However, statistical analysis suggested that there is no significance difference between control and plain liposome after day 30. The effect of plain liposomes on cell viability has been observed by other research groups [77]. There were no significant body weight variations of the nude mice in all the groups after treatments except free Dox treated group. Significant bodyweight reduction was found in the free Dox treated mice after treatment compared with the control group as well as the PS5-DoxL group (Figure 11C), indicating that there might be an obvious toxic side effects in the Free Dox group at the Dox dose administrated in this experiment. Therefore, PS5-DoxL had significant antitumor efficacy and almost no toxic side effects.

Figures 12D and Figure S16 show H&E-stained pictures of the tumor tissues and primary organs. From previous studies, we know, bone marrow suppression and cardiotoxicity are the most serious side effects of Dox in clinical use [78]. The heart and spleen of the mice in Free Dox, 5-Dox, and NPS5-DoxL treatment groups showed a varied level of toxic effects revealed in the histopathological analysis. 5-Dox contained dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as a cosolvent that might be causing additional toxicity in the heart and spleen along with the Dox, while nonspecific drug release and accumulation of NPS5-DoxL might lead to heart tissue damage. However, PS5-DoxL treated group had the least toxic effects found on histopathological analysis on all the major organs compared to control treatment groups (Figure S16). Nonetheless, all the Dox-treated groups showed varied levels of tumor necrosis. The PS5-DoxL group, in particular, displayed substantially more extensive multiple foci necroses in tumor sites showed in Figure 12D. This indicated that PS5-DoxL had the best tumor-killing potential, which corresponded to the anticancer findings in vivo. The above results further confirmed that the HER2 protein targeting peptide conjugated pH-sensitive release properties of PS5-DoxL significantly improved the antitumor effect with reduced side effects of Dox in vivo, which showed considerable promise as a liposomal delivery method for HER2 positive, aggressive form of cancer treatment.

Conclusion

In summary, a pH-sensitive liposome formulation containing peptidomimetic doxorubicin conjugate was developed targeting HER2 positive lung and breast cancer cells. To the best of our knowledge, the present study marks the first time reporting of the stimuli-sensitive liposomal formulation of the doxorubicin-peptidomimetic conjugate in a targeted therapeutic approach. The drug release studies in different pH conditions showed the liposome could release drug conjugate, and cellular uptake was sufficiently high in lower pH conditions in HER2 positive cancer cells found in both in vitro cellular and 3D tumor spheroid model. The PS5-DoxL formulation showed higher specificity toward HER2 positive lung and breast cancer cells supported by in vitro 3D-MCTS antiproliferative, antitumor, and drug uptake assays congruent to in vitro cellular results. In vivo animal results also validated the efficacy and safety of PS5-DoxL compared with other treatment groups. Therefore, the PS5-DoxL liposomal delivery system could significantly improve cell uptake selectively toward HER2 positive cancer cell line and increase the tumor accumulation of Dox, leading to the effective enhancement of antitumor efficacy with reduction of off-target side effects.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

A pH-sensitive liposome containing peptidomimetic-doxorubicin conjugate was developed The formulation was able to release more the drug conjugate at pH 6.5 comapred to 7.4 The cellular uptake of the conjugate was high in HER2 positive cancer cells

The formulation exhibited anticancer activity in 3D tumor spheroid model.

The formulation was able to suppress the NSCLC tumor in mice model.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Dr. Matthaiolampakis for allowing us to use the particle size analysis instrument and core facility at Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, for using TEM and Cryo-TEM, core facility at Biology ULM for the use of microscope facility. Also, we would like to thank Dr. Abu Baker Siddique for his guidance on different techniques.

Funding:

Part of the funding for this project was supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the National Institutes of Health (1R01CA255176-01).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Credit statement

Seetharama D. Jois and Jafrin Jobayer Sonju: Conceptualization, Methodology; Data curation, Writing- Original draft preparation. Seetharama D. Jois, Jafrin Jobayer Sonju, Achyut Dahal, Sitanshu Singh. Supervision: Seetharama D. Jois; Validation: Jafrin Jobayer Sonju: Writing-Reviewing and Editing: Seetharama D. Jois, Jafrin Jobayer Sonju, Achyut Dahal, Sitanshu Singh. Statistical Analysis and writing. Dr. Johnson, Tumor slide analysis and writing: Dr. Xin Gu. Histopathological analysis and writing Jafrin Jobayer Sonju, Mohan Reddy Muthumula, and Sharon A Meyer.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2020;70(3):145–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oh DY, Bang YJ. HER2-targeted therapies - a role beyond breast cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020. Jan;17(1):33–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heinmoller P, Gross C, Beyser K, et al. HER2 status in non-small cell lung cancer: results from patient screening for enrollment to a phase II study of herceptin. Clin Cancer Res. 2003. Nov 1;9(14):5238–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu S, Li S, Hai J, et al. Targeting HER2 Aberrations in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer with Osimertinib. Clin Cancer Res. 2018. Jun 1;24(11):2594–2604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mar N, Vredenburgh JJ, Wasser JS. Targeting HER2 in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2015. Mar;87(3):220–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang SE, Narasanna A, Perez-Torres M, et al. HER2 kinase domain mutation results in constitutive phosphorylation and activation of HER2 and EGFR and resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Cancer Cell. 2006. Jul;10(1):25–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slamon DJ, Godolphin W, Jones LA, et al. Studies of the HER-2/neu proto-oncogene in human breast and ovarian cancer. Science. 1989. May 12;244(4905):707–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slamon DJ, Clark GM, Wong SG, et al. Human breast cancer: correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER-2/neu oncogene. Science. 1987. Jan 9;235(4785):177–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu L, Shao X, Gao W, et al. The Role of Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 as a Prognostic Factor in Lung Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Published Data. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2010. 2010/December/01/;5(12):1922–1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ettmayer P, Amidon GL, Clement B, et al. Lessons learned from marketed and investigational prodrugs. J Med Chem. 2004. May 6;47(10):2393–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Z, Robinson JT, Sun X, et al. PEGylated nanographene oxide for delivery of water-insoluble cancer drugs. J Am Chem Soc. 2008. Aug 20;130(33):10876–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhunia D, Saha A, Adak A, et al. A dual functional liposome specifically targets melanoma cells through integrin and ephrin receptors [10.1039/C6RA23864E]. RSC Advances. 2016;6(114):113487–113491. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luk BT, Zhang L. Cell membrane-camouflaged nanoparticles for drug delivery. J Control Release. 2015. Dec 28;220(Pt B):600–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J, Wang Y, Zhu Y, et al. Recent advances in delivery of drug-nucleic acid combinations for cancer treatment. J Control Release. 2013. Dec 10;172(2):589–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marin JJ, Romero MR, Blazquez AG, et al. Importance and limitations of chemotherapy among the available treatments for gastrointestinal tumours. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2009. Feb;9(2):162–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alexis F, Pridgen EM, Langer R, et al. Nanoparticle technologies for cancer therapy. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2010. (197):55–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minotti G, Menna P, Salvatorelli E, et al. Anthracyclines: molecular advances and pharmacologic developments in antitumor activity and cardiotoxicity. Pharmacol Rev. 2004. Jun;56(2):185–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chittasupho C, Lirdprapamongkol K, Kewsuwan P, et al. Targeted delivery of doxorubicin to A549 lung cancer cells by CXCR4 antagonist conjugated PLGA nanoparticles. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2014. Oct;88(2):529–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwok JC, Richardson DR. Anthracyclines induce accumulation of iron in ferritin in myocardial and neoplastic cells: inhibition of the ferritin iron mobilization pathway. Mol Pharmacol. 2003. Apr;63(4):849–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gottesman MM. Mechanisms of cancer drug resistance. Annu Rev Med. 2002;53:615–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Longley DB, Johnston PG. Molecular mechanisms of drug resistance. J Pathol. 2005. Jan;205(2):275–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stavrovskaya AA. Cellular mechanisms of multidrug resistance of tumor cells. Biochemistry (Mosc). 2000. Jan;65(1):95–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang XQ, Xu X, Lam R, et al. Strategy for increasing drug solubility and efficacy through covalent attachment to polyvalent DNA-nanoparticle conjugates. ACS Nano. 2011. Sep 27;5(9):6962–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsumura Y Poly (amino acid) micelle nanocarriers in preclinical and clinical studies. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008. May 22;60(8):899–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Satyanarayanajois S, Villalba S, Jianchao L, et al. Design, synthesis, and docking studies of peptidomimetics based on HER2-herceptin binding site with potential antiproliferative activity against breast cancer cell lines. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2009. Sep;74(3):246–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pallerla S, Gauthier T, Sable R, et al. Design of a doxorubicin-peptidomimetic conjugate that targets HER2-positive cancer cells. Eur J Med Chem. 2017. Jan 5;125:914–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Immordino ML, Dosio F, Cattel L. Stealth liposomes: review of the basic science, rationale, and clinical applications, existing and potential. Int J Nanomedicine. 2006;1(3):297–315. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deshpande PP, Biswas S, Torchilin VP. Current trends in the use of liposomes for tumor targeting. Nanomedicine (Lond). 2013. Sep;8(9):1509–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ashley JD, Stefanick JF, Schroeder VA, et al. Liposomal bortezomib nanoparticles via boronic ester prodrug formulation for improved therapeutic efficacy in vivo. J Med Chem. 2014. Jun 26;57(12):5282–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiao H, Stefanick JF, Jia X, et al. Micellar nanoparticle formation via electrostatic interactions for delivering multinuclear platinum(II) drugs. Chem Commun (Camb). 2013. May 25;49(42):4809–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noble GT, Stefanick JF, Ashley JD, et al. Ligand-targeted liposome design: challenges and fundamental considerations. Trends Biotechnol. 2014. Jan;32(1):32–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paraskar AS, Soni S, Chin KT, et al. Harnessing structure-activity relationship to engineer a cisplatin nanoparticle for enhanced antitumor efficacy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010. Jul 13;107(28):12435–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]