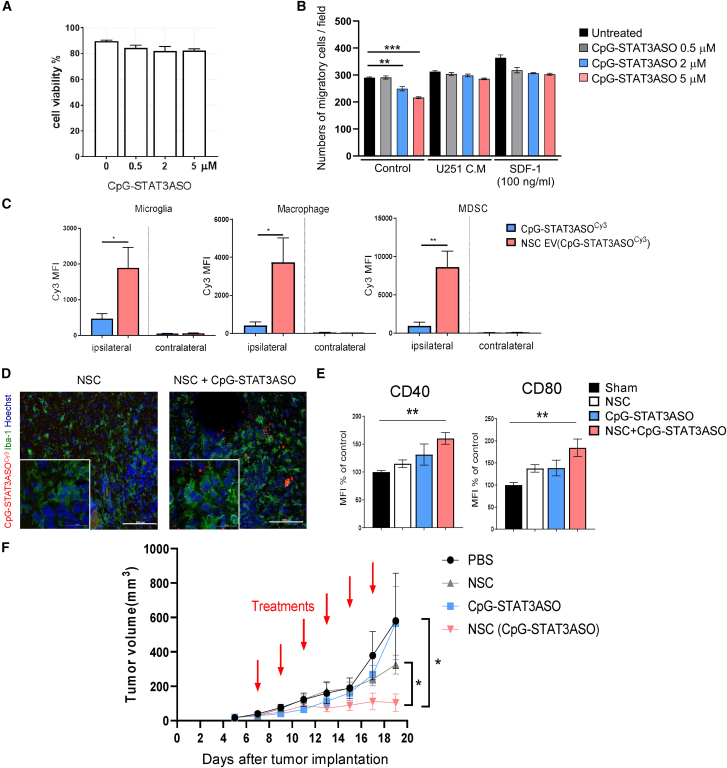

Figure 4.

NSCs deliver CpG-STAT3ASO to glioma-associated myeloid cells and inhibit growth of GL261 tumors in vivo

(A and B) CpG-STAT3ASO loading does not affect NSC viability but can influence cell migration. The NSC viability (A) was measured using flow cytometry after 24 h incubation with CpG-STAT3ASO at various dosing. (B) NSCs migration was assessed using transwell assay; means ± SEM (n = 4); ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001. (C) NSCs are an effective vehicle for CpG-STAT3ASO delivery into the glioma-associated myeloid cells. GL261 glioma-bearing mice were injected peritumorally with 1 × 106 NSCs loaded for 24 h with CpG-STAT3ASOCy3 or with the corresponding amount of oligonucleotide alone (0.05 mg/kg). After 1 day, the percentage of CpG-STAT3ASOCy3 uptake was assessed in glioma-associated myeloid cells using flow cytometry; means ± SEM (n = 3); ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01. (D) CpG-STAT3ASOCy3 is detectable in Iba1+ glioma-associated microglia after NSC-mediated intracranial delivery. Mice were treated as in (A), and brains were harvested after 24 h for immunofluorescent staining and confocal imaging. Shown are representative images (n = 4); scale bars represent 100 μm (20 μm in insets). (E) NSC delivery of CpG-STAT3ASO results in immune activation of glioma-associated microglia (CD11b+CD45hi); shown are means ± SEM (n = 5); ∗∗p < 0.01. (F) Mice with established GL261 tumors were treated using every other day i.t. injections of 1 × 106 NSCs loaded with CpG-STAT3ASO, native NSCs, CpG-STAT3ASO alone at the equivalent amount (0.05 mg/kg, 20× lower than the effective dose for a naked oligonucleotide), or PBS; shown are means ± SEM (n = 5); ∗p < 0.05.