Abstract

We performed a pilot study among young African-American men who have sex with men (AAMSM) of a real-time electronic adherence monitoring (EAM) in Chicago to explore acceptability and feasibility of EAM and to inform intervention development. We recruited 40 young AAMSM living with HIV on ART to participate in up to 3 months of monitoring with the Wisepill device. Participants were interviewed at baseline, in response to the first true adjudicated 1-dose, 3-day, and 7-day misses, and at the end of monitoring. Reasons for missing doses and the acceptability and feasibility of electronic monitoring were assessed using mixed methods.

The median participant observation time was 90 days (N=40). For 21 participants with 90 days of follow-up, <90% and <80% adherence occurred in 82% and 79%, respectively in at least one of their monitored months (n=63 monitored months). The participants generally found the proposed intervention acceptable and useful. Although seven participants said the device attracted attention, none said it led to disclosure of their HIV status. This study found real-time EAM to be generally acceptable and feasible among YAAMSM living with HIV in Chicago. Future work will develop a triaged real-time EAM intervention including text alerts following detection of nonadherence.

Keywords: electronic adherence monitoring, adherence, men who have sex with men, Wisepill, African American, text message

Introduction

Maintaining optimal antiretroviral adherence in persons living with HIV reduces morbidity, mortality, emergence of resistant virus, and risk for transmission to others(Bangsberg et al., 2000; Bangsberg et al., 2001; Cohen et al., 2011; Paterson et al., 2000a; Wood et al., 2003). However, there are many barriers and facilitators of adherence such as forgetting and having social support, respectively(Casale et al., 2015; Gibbie, Hay, Hutchison, & Mijch, 2007; Goldenberg & Stephenson, 2015; Golin et al., 2002; Gonzalez et al., 2004; Hays, Turner, & Coates, 1992; Heaney & Israel, 2008; Juday, Gupta, Grimm, Wagner, & Kim, 2011; Kelly, Hartman, Graham, Kallen, & Giordano, 2014; Kyser et al., 2011a; Langebeek et al., 2014; Remien et al., 2005; Sankar, Luborsky, Schuman, & Roberts, 2002; Shubber et al., 2016; Stumbo, Wrubel, & Johnson, 2011; Woodward & Pantalone, 2012; Wrubel, Stumbo, & Johnson, 2008; Wrubel, Stumbo, & Johnson, 2010). Social support may provide empathy (emotional support), information (informational support), or tangible services (instrumental support)(Heaney & Israel, 2008) It may also facilitate adherence by improving mental health, increasing HIV knowledge, and providing accountability to a trusted close contact(Goldenberg & Stephenson, 2015; McDowell & Serovich, 2007). A combination approach that targets overcoming forgetting along with real-time responsive social support might be more effective than a single approach intervention.

Scheduled text messages and reminder alerts have been used effectively in some studies as components of antiretroviral adherence interventions(Dowshen, Kuhns, Johnson, Holoyda, & Garofalo, 2012; Lester et al., 2010; Pop-Eleches et al., 2011) Real-time text message alerts might be superior to pre-programmed periodic texts that could lead to an effect burn out(Boker, Feetham, Armstrong, Purcell, & Jacobe, 2012; Furberg et al., 2012; Hanauer, Wentzell, Laffel, & Laffel, 2009) Real-time triggered alerts can be set to only alert if a missed window of time is detected.

Real-time electronic adherence monitoring (EAM) has been explored as part of interventions to improve adherence. In the US, small studies have examined the feasibility and acceptability of these interventions in persons living with HIV. In Atlanta, Pellowski and colleagues found that although a monitoring device accompanied with counseling was considered acceptable, nearly half of the participants were uncomfortable with monitoring(Pellowski et al., 2014) Stringer and colleagues found that rural Alabama African-American women reported feeling a sense of accountability that might motivate better adherence(Stringer et al., 2019) Focus groups that we performed with young African American men who have sex with men (YAAMSM) in Chicago revealed concern about unwanted attention to the device(Dworkin et al., 2019)

Randomized clinical trials of EAM have also been performed in Africa and China. Haberer and colleagues performed a pilot randomized controlled trial in Uganda in 62 men and women living with HIV(Haberer et al., 2016) This study demonstrated higher adherence for the arm that employed a combination of scheduled text message reminders followed by reminders that were triggered by a late or missed dose and text message notification to social supporters for adherence lapses >48 hours, compared to the control group. In South Africa, Orrell and colleagues performed a randomized controlled trial in 230 men and women living with HIV (Orrell et al., 2015) comparing standard of care along with three pretreatment education sessions to an intervention that included standard of care and automated text reminders in response to real-time detected doses more than 30 minutes late. The real-time EAM intervention arm did not improve average adherence but did decrease sustained interruptions in adherence. In a randomized clinical trial among 120 men and women living with HIV in China, Sabin and colleagues found that personalized real-time reminders triggered when missed doses were detected, coupled with monthly adherence counseling when suboptimal adherence occurred, increased the likelihood of achieving >95% adherence compared to a control group(Sabin et al., 2015)

Here we report the results of a pilot study of real-time EAM with young AAMSM living with HIV in Chicago to explore the acceptability and feasibility of EAM and to describe the frequency of and reasons for missing doses. Our overarching objective is to develop a combination intervention that has three levels of real-time EAM triggered support that varies with duration of missed dose event duration. A 1-dose miss would receive a real-time text alert, a 3-day miss would notify a social support person, and a 7-day miss would notify a healthcare provider.

Methods

Study procedures and participants

We recruited 40 young AAMSM to participate in 3 months of EAM in Chicago during April 2017 through April 2019. Participants were recruited from four University of Illinois at Chicago Community Outreach Intervention Project (COIP) sites located in high HIV incidence areas of the city and the University of Illinois at Chicago HIV clinic using fliers and word of mouth. Inclusion criteria for the study included being age 18–34 years, African American, MSM, living with HIV, on ART for at least 3 months by self-report, owning a working cell phone, and agreeing to be interviewed in response to detected missed doses. We also determined if the patients had a detectable or undetectable viral load in the past 12 months.

All procedures were approved by the University of Illinois at Chicago School of Public Health Institutional Review Board. Upon enrollment, informed consent was obtained. After consent, each participant was administered a baseline interview that gathered information on demographic characteristics, adherence-related social support (e.g., close personal contacts), health information (i.e. self-reported overall health as a Likert scale, comorbid conditions and categorical most recent CD4 count), drug and alcohol use, and treatment history. To explore coping self-efficacy, we asked three questions from the HIV Adherence Self-efficacy Scale (ASES)(Johnson et al., 2007). We also asked participants how they ranked their communication with their healthcare provider and how comfortable they were with their knowledge of HIV medication and possible side effects. Subjects were paid $40 at enrollment and $50 after the monitoring.

Electronic adherence monitoring

Each participant was given and instructed on the use of a Wisepill EAM device (Wisepill Technologies, Capetown, South Africa). This device is approximately the size of a flip phone and contains a plastic pill container. It uses an embedded global mobile communications chip to capture real-time openings, a proxy for adherence, by sending a signal to a central server at each opening. The central server was programmed to detect if the device was opened in a 3-hour window of time each day during the 3-months of observation. The window corresponded to the time when participants reported routinely taking their ART. A text message alert of a missed window was sent to the study research assistant’s phone. Device openings were also reviewed to identify durations of no openings of 3 and 7-day durations.

Monitoring Interviews

The research assistant contacted participants by text the same day as a missed dose, or the next day if the dose window of time was at night, to adjudicate the miss (i.e., determine if the lack of signal received by the server actually represented a missed dose by asking the participant). A telephone interview was performed immediately or as soon as possible (typically within 24 hours) if adjudication determined a true missed dose for the first missed window, first consecutive 3-day miss, and first consecutive 7-day miss. These interviews included closed and open-ended questions that gathered information about feasibility, acceptability, and causes of true misses. Feasibility of our monitoring approach with adjudication was assessed by the number of call attempts and number of true misses. Acceptability was also explored during these missed dose interviews with questions concerning if the participant felt receiving contact from the research assistant in response to a miss had any effect on taking the missed dose that same day and their plans for not missing ART in the future if they had any. We also asked questions about their experience with the wireless container such as if it attracted any attention and, if it did, then did it lead to disclosure of their HIV status. Participants were also asked if anything prevented them from taking the dose, how they felt about missing ART, and if anyone in their life tried to influence the taking of the dose.

An additional face-to-face interview was performed at the end of the observation period to assess participant’s EAM experience and features of the proposed intervention. It also employed closed and open-ended questions. We asked for their thoughts on a triaged approach of EAM triggered text message notification in real-time for a missing 1 dose (patient), 3 days (social support), and 7 days (healthcare provider). In summary, participants were interviewed at study entry, then again upon their first 1-dose, 3-day, and 7-day miss, and then one more time at the end of their follow time.

Data Analysis

We employed a mixed methods approach. For quantitative data, frequencies were determined for participant characteristics or all 40 enrolled participants. Unless specified, most of the other data analyses were performed on the 32 participants who had at least 2 weeks of follow-up and adjudication including determining reasons for 1-dose, 3-day, and 7-day adjudicated missed events; and acceptability questions. We explored with bivariate analysis if having a recent detectable viral load at enrollment was associated with having an adjudicated true 3-day miss. For qualitative data (open-ended questions), transcripts were reviewed after listing each question and all of the participant’s responses in a Word file. Narratives were coded based upon pre-determined themes (categories) that we were exploring to provide insight into YAAMSM experiences related to adherence and the proposed intervention. QDA (Qualitative Data Analysis Software) Miner Lite v2.0.5 was used to label narratives per our pre-determined themes. These themes included privacy, adherence influencing individuals, social support, and acceptability of the proposed intervention. These questions were not asked to generate theory. Two team members (MD and PP) reviewed transcripts of the responses initially to code for the themes. Then illustrative examples of interviews were selected that exemplified these themes. The transcripts and the selected examples were then shared with WW, JH, AJ, and RG for discussion, feedback, and final selection.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Demographic characteristics and health information of the 40 participants are summarized in Table 1. The median age was 28 years (range 19–34 years). The median number of doses missed in the past 4 days was 0 (range 0–4). Concerning adherence-related social support, 22 men did not have a close personal contact (such as a family member or partner) who currently helped them remember to take their medication. Among these men, most (n=15, 68%) did have someone they could ask to help in this way if they needed help. For the 18 men who had at least one close personal contact currently helping them, these support persons were a mother (5, 28%), sister (1, 6%), sexual partner (4, 22%), aunt (1, 5%), friend (2, 11%), or other person who is not a close relative (5, 28%). On a scale of 1–10, the median overall health self-reported by the participants was 9 (range 4–10). For those who drank alcohol (24, 60%), the median number of drinks they have on a typical day was 3 (range 1.5–13.5 drinks) and one participant responded “unlimited.”

Table 1.

Characteristics of young African American men who have sex with men participants (N=40). For Likert scales, 0 was least and 10 was most.

| Characteristics | N=40 (%) |

|---|---|

| Age in years | |

| 18–24 | 7 (18) |

| 25–34 | 33 (83) |

|

| |

| Viral load detectable in the past 12 months | |

| Yes | 7 (18) |

| No | 15 (38) |

| Unvalidated | 18 (45) |

|

| |

| Most recent self-reported CD4 count | |

| <200 cells/ml | 11 (28) |

| 200 to 350 cells/ml | 6 (15) |

| >350 cells/ml | 13 (33) |

| Do not remember | 10 (25) |

|

| |

| Comorbid conditions* | |

| Hepatitis B or C | 3 (8) |

| Mental health disorder (depression, schizophrenia, bipolar, or anxiety) |

19 (48) |

| Hypercholesterolemia or hypertriglyceridemia | 2 (5) |

| Asthma | 7 (18) |

| Diabetes | 0 (0) |

| Neurologic condition (seizure disorder or neuropathy) | 1 (3) |

| Selected comorbid conditions (bronchitis, eczema, heart disease, hypertension, pseudoseizures, rheumatoid arthritis, and thrombocytopenia) | 5 (13) |

|

| |

| In the previous week, frequency of depression | |

| Rarely or none of the time | 17 (43) |

| Some or little of the time | 15 (38) |

| Occasionally or a moderate amount of time | 5 (13) |

| Most or all of the time | 3 (8) |

|

| |

| Duration taking antiretroviral therapy (in years) | |

| Less than 1 year | 4 (10) |

| 1 to 2 years | 7 (18) |

| ≥ 3 years | 29 (73) |

|

| |

| Number of times per day takes ART | |

| Once daily | 39 (98) |

| Twice daily | 1 (3) |

|

| |

| Total of all pills taken per day | |

| 1 | 15 (38) |

| 2 | 9 (23) |

| 3 | 7 (18) |

| 4 | 5 (13) |

| ≥ 5 | 4 (10) |

|

| |

| Self reported number of doses of ART missed in the past 4 days | |

| 0 | 21 (53) |

| 1 | 11 (28) |

| 2 | 6 (15) |

| >3 | 2 (5) |

|

| |

| Takes HIV medicine out of the bottle provided by the pharmacy and transfers it to another bottle (n=35)** | |

| Yes | 9 (26) |

| No | 26 (74) |

|

| |

| If a dose of HIV medication is missed | |

| Can take it later the same day | 35 (88) |

| Wait until the next day and take that day’s dose | 4 (10) |

| Wait until the next day and take 2 doses | 0 (0) |

| Don’t know what to do | 0 (0) |

| Other (take it when remembering) | 1 (3) |

|

| |

| Employment status | |

| Full-time | 12 (30) |

| Part-time | 8 (20) |

| Unemployed | 20 (50) |

|

| |

| Highest level of education | |

| 10th grade or less | 1 (3) |

| 11th grade | 1 (3) |

| 12th grade | 22 (55) |

| More than high school | 16 (40) |

|

| |

| Self-reported ability to read | |

| Excellent | 25 (63) |

| Good | 12 (30) |

| Fair | 3 (8) |

| Poor | 0 (0) |

|

| |

| Relationship status | |

| Single | 27 (68) |

| Partnered | 11 (28) |

| Married | 1 (3) |

| Other | 1 (3) |

|

| |

| Has a close personal contact that currently helps him remember to take medication | |

| Yes | 18 (45) |

| No | 22 (55) |

|

| |

| Used the following drugs within the past 6 months* | |

| Marijuana | 32 (80) |

| Heroin | 1 (3) |

| Cocaine (including crack) | 8 (20) |

| Meth or amphetamines | 5 (13) |

| Inhalants | 2 (5) |

|

| |

| How many days per week alcohol is drunk | |

| 0 | 16 (40) |

| 1–2 | 20 (50) |

| 3–4 | 3 (8) |

| 5 or more | 1 (3) |

|

| |

| Generally, how would you rank the communication between your healthcare provider and yourself? (Likert scale, median=10 )*** | |

| 0–4 | 0 (0) |

| 5–7 | 6 (15) |

| 8–10 | 34 (85) |

|

| |

| How comfortable are you that you generally know what you need to know about your HIV medication? (Likert scale, median=9.5) | |

| 0–4 | 0 (0) |

| 5–7 | 6 (15) |

| 8–10 | 34 (85) |

|

| |

| How comfortable are you that you generally know about the possible side effects of your HIV medication? (Likert scale, median=8) | |

| 0–4 | 4 (10) |

| 5–7 | 10 (25) |

| 8–10 | 26 (65) |

|

| |

| Duration monitored | |

| 90 days | 21 |

| 89 | 2 |

| 87 | 3 |

| 76 days | 1 |

| 60 days | 1 |

| 57 days | 1 |

| 55 days | 1 |

| 26 days | 1 |

| 21 days | 1 |

| 15 days | 1 |

| 8 days | 1 |

| 5 days | 1 |

| 0 days | 5 |

Not mutually exclusive

Not referring to the Wisepill device

Higher scores indicate better communication/comfort

Electronic Adherence Monitoring

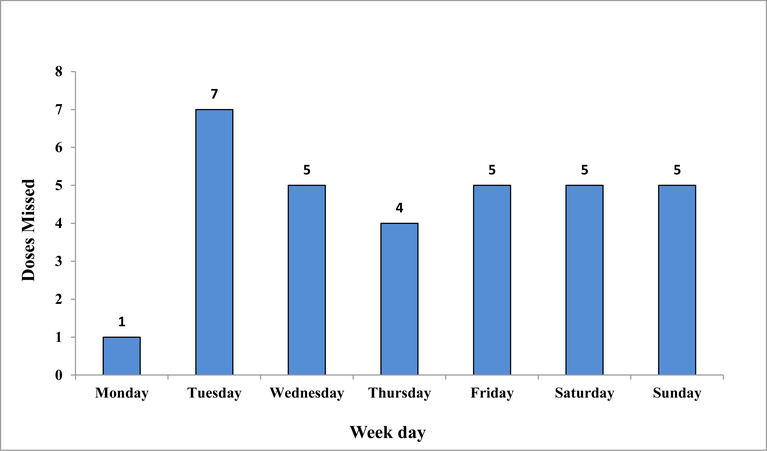

Among the 40 participants, the median participant observation time was 90 days (interquartile range 55.5 – 90.0), mean observation time 67 days). Five were never responsive after the enrollment interview, one was unreachable after a few days of follow-up, and one was generally unreliable and uncooperative with the study protocol but did participate in adjudication of his 1-dose miss. An additional two exited the study – returning the device without having had misses adjudicated and without performing a follow-up interview. They were unhappy with getting contacted by the research assistant in response to electronically detected missed events that needed adjudication. Among those with at least 2 weeks follow-up and adjudication (n=32), 100% missed at least 1 day, 14 (45%) missed 3 consecutive days and 4 (13%) missed 7 consecutive days. The distribution of the day of the week that each of the first adjudicated 1-dose miss occurred did not reveal any weekend clustering (Figure 1). For the 21 participants with 3 full months (90 days) of follow-up, <90% and <80% adherence occurred in 82% and 79%, respectively in at least one of their monitored months (n=63 monitored months). For those who had a morning dose window (n=15) and therefore an opportunity to receive a text message the same day in response to their missed dose, five took the dose later the same day after contact from the research assistant, three before contact from the research assistant, and seven not at all that day. Those who had a recent detectable viral load at enrollment (n=13) were at 1.5 times increased risk of having an adjudicated true 3-day miss compared to those with undetectable viral load (n= 19) (95% confidence intervals 0.67–3.17).

Figure 1.

Distribution of the days that each first adjudicated missed dose occurred among 32 young AAMSM monitored by electronic adherence monitoring.

Monitoring Interviews

Unless specified, the following results pertain to the first missed dose among the 32 participants with at least 2 weeks follow-up and adjudication. The frequency of reasons for missed doses by participants during EAM is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Frequency of Reasons for Missed Doses by Participants During 3-Month Monitoring among 32 young AAMSM monitored by electronic adherence monitoring.

| 1 dose (n=32) | n (%) |

|

| |

| Forgetting | 19 (59) |

| Rushing off to work or to get somewhere | 4 (13) |

| Worked late and was tired so fell asleep | 2 (6) |

| Did not forget. Just haven’t taken it. | 1 (3) |

| Caught up in July 4th riots | 1 (3) |

| Woke up late past window | 1 (3) |

| Misplaced bottle in transportation | 1 (3) |

| Pharmacy didn’t Fedex medicine | 1 (3) |

| Appointment with doctor during the window | 1 (3) |

| Went out drinking | 1 (3) |

|

| |

| 3 days (n=13) | |

|

| |

| A lot going on | 4 (31) |

| No pill bottle with the participant | 3 (23) |

| Loss of insurance | 2 (15) |

| Ran out of medicine | 1 (8) |

| Theft | 1 (8) |

| Hospitalization | 1 (8) |

| No reason. Didn’t take the pills | 1 (8) |

|

| |

| 7 days (n=4) | |

|

| |

| No pill bottle with the participant | 1 (25) |

| Theft | 1 (25) |

| Insurance loss | 1 (25) |

| Ran out of medicine | 1 (25) |

Adjudicated false missed doses

During the period from commencement of monitoring to the first adjudicated missed window, there were 15 electronically detected misses that were adjudicated as not a miss out of a total of 47 electronically detected misses. Participants stated they had a reason not to use the Wisepill device such as using their original pill bottle when staying at someone else’s house and pocket dosing (i.e., removal of multiple doses at one time for subsequent dosing).

Influencing individual/factors

Only one participant stated he had someone in his life who tried to influence the taking of the dose (his spouse). When asked if anything prevented them from taking the dose, most participants said no except one who stated it was “just a busy day,” one who laughed while explaining “just memory loss,” and one who was concerned that “everyone was there.”

Concern for missed doses

When asked if they were concerned about missing doses, seven participants said yes. The reasons included staying healthy, controlling viral load, and avoiding development of resistance. Twenty-three said no, including several whose responses elaborated and indicated adherence self-efficacy. For example, “I am not concerned, I mean I am working on it,” “…if I don’t take it in the evening, I take it later,” and “I know I’ll take them. One also said, “Not really, but I should be.”

Social support

Most participants approved of having a social support person contact them in response to missed doses, but some either would not want it or were ambivalent (Table 3). Those who approved of it expressed they were comfortable with communicating about adherence and appreciated the motivation and support. Alternatively, negative responses including taking responsibility and distrust.

Table 3.

Illustrative quotes from participants concerning social support and acceptability of electronic monitoring.

| In Favor of Social Support Involvement |

| “I think it would be a lot helpful because it is coming from a friend. They can give you the truth…They’ll be like ‘Aren’t you worried about your life?’” |

| “It wouldn’t matter who contacted me…At least I know someone’s concerned about me.” |

| Concerned About Social Support Involvement |

| “As long as I take it regularly, I don’t have to worry about that person calling me about that.” |

| “When you are an adult, you do things on your own time.” |

| “I don’t want nobody to stress me about my health if I’m not stressing about my health.” |

| “Friends come and go every day. You don’t know whether they’ll go and spread.” |

| “I don’t really have anyone that would commit to it.” |

| “Some days I don’t want to take my medicine.” |

| Acceptability of electronic monitoring |

| “It made me more responsible. Kind of like accountability partner in a pill bottle.” |

| “When you do call me and when I do open it I feel better,” |

| “I actually liked it. Coz like, it’s almost like you’re a kid and your mom, and it makes you want to do it right.” |

| Concerns for electronic monitoring |

| “I forget to take it all the time. I take it when I remember. When so many things happening - but it concerns me, knowing calls would be coming up.” |

| “It was kind of like frustrating at first.” |

With regard to how participants felt about having a healthcare provider contacting them, there was general approval. For example, some participants thought it would be motivating. One said, “It will make me feel like I need to work harder to stay and get back on track.”

Acceptability of the intervention

In follow-up interviews (n=31), the participants generally found the proposed intervention acceptable and useful. Responses to follow-up questions after the monitoring period are summarized in Table 4. Seven participants (23%) said the device attracted attention. Among those who said it did, none said it led to disclosure of their HIV status. One participant said they got a lot of attention, “People ask, ‘What is that big black thing?’…I told my friends if I miss, someone takes notice.”

Table 4.

Acceptability of wireless monitoring among 31 young African American men who have sex with men as determined at the end of 3 months follow-up.

| Question | Response |

|---|---|

| Was the Wisepill device easy to use? Yes No Did not commit to ‘yes’ or ‘no’ |

29 (94%) 0 (0%) 2 (6) |

| Was the Wisepill device convenient? Yes No |

29 (94) 2 (6) |

| Did the Wisepill device attract any attention? Yes No |

7 (23%) 24 (77%) |

| Did they think receiving a text because of device monitoring would have any effect on their medication taking in the future? Yes No |

27 (87%) 4 (13%) |

| Did they think that having a close contact chosen by contact them in response to a 3-day miss would have any effect on their medication taking in the future? Yes No Mixed |

22 (71%) 7 (23%) 2 (6%) |

| Did they think that having a healthcare provider or case manager contact them in response to a 7-day miss would have any effect on their medication taking in the future? Yes No |

28 (90%) 3 (10%) |

When asked if they felt that receiving contact from the research assistant in response to a miss had any effect on taking the missed dose that same day 17 participants (55%) said yes. One participant stated, “Yes, it makes me think more about taking it.” However, one stated, “The only difference is someone’s monitoring.” Eighteen (58%) expressed a plan for not missing ART in the future. For example six participants might take ART with them including one who stated, “I definitely need to get a little pill bottle to get a case to put the pill in and bring it in the bag with me.” When asked how they felt about having their pill taking monitored, responses nearly all were either enthusiastic or neutral (Table 3).

Most (27, 87%) said that receiving a text because the bottle was monitoring their adherence would have an effect on whether they take their medicine in the future. One participant liked it the reminder, saying, “…when you text me - ‘Oh shit I didn’t take the pill. Let me go get the pill.’” Another expressed, “I got someone else that cares about my health. It’s not on me but someone else.” Another offered, “You never know you may be having suicidal thoughts or depression or not having medicine. So, when someone texts asking what happened, gives me a chance to say I’m having depression or don’t feel like eating or moving and waiting until it becomes worse.” Another said, “It would help. There are people who don’t want to take their medicine. They may look at the bottle and not take it. It’s a mental choice.” However, one disagreed stating, “I’m usually on top of things.”

Feasibility

For the 32 participants with at least 2 weeks follow-up and adjudication, the median number of call attempts to adjudicate the electronically detected first missed dose was 1 (range 1–7). The number of true missed dose events out of all electronically detected miss events was 32/47 (68%) for 1 missed dose (among 32 participants detected with a miss), 13/50 (26%) for 3-day misses (among 28 participants detected with a 3-day miss), and 4/21 (19%) for 7-day misses (among 17 participants detected with a 7-day miss). The participants who had less than 14 days of follow-up were all uncooperative with adjudication or were completely unresponsive, hence exiting or becoming lost to follow-up early.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first exploration of EAM in an MSM population living with HIV, specifically young AAMSM living with HIV in Chicago. Although an intervention incorporating real-time EAM may be helpful to persons living with HIV in general, we prioritized young AAMSM because the odds of adherence is lower in African Americans than whites(Golin et al., 2002; Kyser et al., 2011b; Mannheimer et al., 2002; Moss et al., 2004; Paterson et al., 2000b; Simoni et al., 2012; Thrasher, Earp, Golin, & Zimmer, 2008). and African American and young patients are more likely to have detectable viral load(Adeyemi, Livak, McLoyd, Smith, & French, 2013).

Acceptability of real-time adherence monitoring has been demonstrated in small studies in rural Uganda among adult ART initiators and in China among injection drug using patients (Bachman DeSilva et al 2013; Musiimenta et al 2018). Acceptability of a real-time nonadherence text alert was also demonstrated in our study. In developing a combination intervention, it will be important to anticipate that some men will not have or will not want to include a social support person (Dworkin et al., 2019). In that case, the intervention might notify a healthcare provider, such as a case manager, of both 3-day and 7-day misses or it might default to only notifying the case manager of a 7-day miss.

A strength of our approach is that it includes communication with a real person and does not involve automated preset interval alerts. Studies that used automated alerts that included communication either in person or by telephone have demonstrated improvement in adherence in HIV-positive and other populations(Lester et al., 2010; Mistry et al., 2015; Sherrard, Struthers, Kearns, Wells, & Mesana, 2009). The real-time component of our approach also minimizes the number of communication events compared to automated messaging which can lead to text message fatigue(Boker et al., 2012; Furberg et al., 2012; Hanauer et al., 2009). Future research might include comparing real-time versus scheduled alerts or offering a choice to patients since scheduled alerts have demonstrated efficacy in a pilot RCT in Uganda in men and women initiating ART (Haberer et al. 2016).

Our study provided several important findings that inform the feasibility of performing further research of an EAM intervention in young AAMSM. First, the high frequency of clinically significant nonadherence affirms the importance of developing interventions for this population. Second, most of these men had a social support person who might serve as the back-up support. Third, the device infrequently attracted unwanted attention and did not lead to disclosure of their HIV status(Haberer et al., 2010). Finally, the median number of call attempts to adjudicate the first missed dose was manageable (one call). Nevertheless, challenges we may expect include that many of the EAM-detected 3-day and 7-day misses were not true misses which may be a burden to those notified of false alerts and that a substantial minority of participants were either unresponsive after the initial interview, uncooperative, or unhappy with being contacted. Although the desire to maintain a good impression of study staff can promote participation, as was observed for some participants in a study in Uganda(Campbell et al., 2019), retention incentives may be important in future research.

One limitation of this study was the small number of participants. However, this was an exploratory study to inform intervention development. Generalizability may be limited as these participants were recruited in one US city from community outreach clinics and one hospital clinic. Additionally, we did not adjudicate every miss but stopped adjudicating once the first event of interest occurred. Continuous adjudication for 3 months might cause more drop out. Finally, determining a true miss by adjudication relied on self-report.

In conclusion, this study supports the objective to develop a triaged real-time EAM combination intervention that includes back-up support levels to real-time missed event alerts. Future work should include a pilot randomized clinical trial to demonstrate preliminary efficacy and identify further acceptability and feasibility issues when involving social support and healthcare providers in the intervention.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Community Outreach Intervention Project sites including Mark Hartfield for assistance with recruitment. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Institute Of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R21NR017097.

Footnotes

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Dr. Haberer is a consultant for Merck & Company.

Declarations

Consent for Publication

Not Applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The University of Illinois at Chicago School of Public Health Institutional Review Board granted ethical approval for this research. All participants signed the informed consent form prior to participation and were assured of confidentiality and anonymity.

Availability of data and materials

Transcripts of focus group data are not available. For further information, contact the lead author.

References

- 1.Adeyemi OM, Livak B, McLoyd P, Smith KY, & French AL (2013). Racial/ethnic disparities in engagement in care and viral suppression in a large urban HIV clinic. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 56(10), 1512–1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachman DeSilva M, Gifford AL, Keyi X, Li Z, Feng C, Brooks M, Harrold M, Yueying H, Gill CJ, Wubin X, Vian T, Haberer J, Bangsberg D, Sabin L. Feasibility and acceptability of a real-time adherence device among HIV-positive IDU patients in China. AIDS Res Treat 2013;2013:957862. doi: 10.1155/2013/957862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bangsberg DR, Hecht FM, Charlebois ED, Zolopa AR, Holodniy M, Sheiner L,… Moss A (2000). Adherence to protease inhibitors, HIV-1 viral load, and development of drug resistance in an indigent population. Aids, 14(4), 357–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bangsberg DR, Perry S, Charlebois ED, Clark RA, Roberston M, Zolopa AR, & Moss A (2001). Non-adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy predicts progression to AIDS. Aids, 15(9), 1181–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boker A, Feetham HJ, Armstrong A, Purcell P, & Jacobe H (2012). Do automated text messages increase adherence to acne therapy? results of a randomized, controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 67(6), 1136–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell JI, Musiimenta A, Burns B, Natukunda S, Musinguzi N, Haberer JE, & Eyal N (2019). The importance of how research participants think they are perceived: Results from an electronic monitoring study of antiretroviral therapy in uganda. AIDS Care, 31(6), 761–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casale M, Cluver L, Crankshaw T, Kuo C, Lachman JM, & Wild LG (2015). Direct and indirect effects of caregiver social support on adolescent psychological outcomes in two south african AIDS-affected communities. American Journal of Community Psychology, 55(3–4), 336–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N,… Pilotto JH (2011). Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. New England Journal of Medicine, 365(6), 493–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dowshen N, Kuhns LM, Johnson A, Holoyda BJ, & Garofalo R (2012). Improving adherence to antiretroviral therapy for youth living with HIV/AIDS: A pilot study using personalized, interactive, daily text message reminders. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 14(2), e51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dworkin MS, Panchal P, Wiebel W, Garofalo R, Haberer JE, & Jimenez A (2019). A triaged real-time alert intervention to improve antiretroviral therapy adherence among young african american men who have sex with men living with HIV: Focus group findings. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furberg RD, Uhrig JD, Bann CM, Lewis MA, Harris JL, Williams P,… Kuhns L (2012). Technical implementation of a multi-component, text message–based intervention for persons living with HIV. JMIR Research Protocols, 1(2), e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibbie T, Hay M, Hutchison CW, & Mijch A (2007). Depression, social support and adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in people living with HIV/AIDS. Sexual Health, 4(4), 227–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldenberg T, & Stephenson R (2015). “The more support you have the better”: Partner support and dyadic HIV care across the continuum for gay and bisexual men. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999), 69 Suppl 1, S73–9. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000576 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golin CE, Liu H, Hays RD, Miller LG, Beck CK, Ickovics J,… Wenger NS (2002). A prospective study of predictors of adherence to combination antiretroviral medication. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 17(10), 756–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzalez JS, Penedo FJ, Antoni MH, Durán RE, McPherson-Baker S, Ironson G,… Schneiderman N (2004). Social support, positive states of mind, and HIV treatment adherence in men and women living with HIV/AIDS. Health Psychology, 23(4), 413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haberer JE, Kahane J, Kigozi I, Emenyonu N, Hunt P, Martin J, & Bangsberg DR (2010). Real-time adherence monitoring for HIV antiretroviral therapy. AIDS and Behavior, 14(6), 1340–1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haberer JE, Musiimenta A, Atukunda EC, Musinguzi N, Wyatt MA, Ware NC, & Bangsberg DR (2016). Short message service (SMS) reminders and real-time adherence monitoring improve antiretroviral therapy adherence in rural uganda. AIDS (London, England), 30(8), 1295–1300. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001021 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanauer DA, Wentzell K, Laffel N, & Laffel LM (2009). Computerized automated reminder diabetes system (CARDS): E-mail and SMS cell phone text messaging reminders to support diabetes management. Diabetes Technology & Therapeutics, 11(2), 99–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hays RB, Turner H, & Coates TJ (1992). Social support, AIDS-related symptoms, and depression among gay men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60(3), 463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heaney CA, & Israel BA (2008). Social networks and social support. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice, 4, 189–210. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson MO, Neilands TB, Dilworth SE, Morin SF, Remien RH, & Chesney MA (2007). The role of self-efficacy in HIV treatment adherence: Validation of the HIV treatment adherence self-efficacy scale (HIV-ASES). Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 30(5), 359–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Juday T, Gupta S, Grimm K, Wagner S, & Kim E (2011). Factors associated with complete adherence to HIV combination antiretroviral therapy. HIV Clinical Trials, 12(2), 71–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kelly JD, Hartman C, Graham J, Kallen MA, & Giordano TP (2014). Social support as a predictor of early diagnosis, linkage, retention, and adherence to HIV care: Results from the steps study. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 25(5), 405–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kyser M, Buchacz K, Bush TJ, Conley LJ, Hammer J, Henry K,… Wood KC (2011a). Factors associated with non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy in the SUN study. AIDS Care, 23(5), 601–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Langebeek N, Gisolf EH, Reiss P, Vervoort SC, Hafsteinsdóttir TB, Richter C,… Nieuwkerk PT (2014). Predictors and correlates of adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) for chronic HIV infection: A meta-analysis. BMC Medicine, 12(1), 142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lester RT, Ritvo P, Mills EJ, Kariri A, Karanja S, Chung MH,… Najafzadeh M (2010). Effects of a mobile phone short message service on antiretroviral treatment adherence in kenya (WelTel Kenya1): A randomised trial. The Lancet, 376(9755), 1838–1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mannheimer S, Friedland G, Matts J, Child C, Chesney M, & Terry Beirn Community Programs for Clinical Research on AIDS. (2002). The consistency of adherence to antiretroviral therapy predicts biologic outcomes for human immunodeficiency virus—infected persons in clinical trials. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 34(8), 1115–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDowell TL, & Serovich J (2007). The effect of perceived and actual social support on the mental health of HIV-positive persons. AIDS Care, 19(10), 1223–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mistry N, Keepanasseril A, Wilczynski NL, Nieuwlaat R, Ravall M, Haynes RB, & Patient Adherence Review Team. (2015). Technology-mediated interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 22(e1), e177–e193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moss AR, Hahn JA, Perry S, Charlebois ED, Guzman D, Clark RA, & Bangsberg DR (2004). Adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in the homeless population in san francisco: A prospective study. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 39(8), 1190–1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Musiimenta A, Atukunda EC, Tumuhimbise W, et al. Acceptability and Feasibility of Real-Time Antiretroviral Therapy Adherence Interventions in Rural Uganda: Mixed-Method Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;6(5):e122. Published 2018 May 17. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.9031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orrell C, Cohen K, Mauff K, Bangsberg DR, Maartens G, & Wood R (2015). A randomized controlled trial of real-time electronic adherence monitoring with text message dosing reminders in people starting first-line antiretroviral therapy. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999), 70(5), 495–502. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000770 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, Brester M, Vergis EN, Squier C,… Singh N (2000a). Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Annals of Internal Medicine, 133(1), 21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pellowski JA, Kalichman SC, White D, Amaral CM, Hoyt G, & Kalichman MO (2014). Real-time medication adherence monitoring intervention: Test of concept in people living with HIV infection. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care : JANAC, 25(6), 646–651. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2014.06.002 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pop-Eleches C, Thirumurthy H, Habyarimana JP, Zivin JG, Goldstein MP, de Walque D,… Bangsberg DR (2011). Mobile phone technologies improve adherence to antiretroviral treatment in a resource-limited setting: A randomized controlled trial of text message reminders. AIDS (London, England), 25(6), 825–834. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834380c1 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Remien RH, Stirratt MJ, Dolezal C, Dognin JS, Wagner GJ, Carballo-Dieguez A,… Jung TM (2005). Couple-focused support to improve HIV medication adherence: A randomized controlled trial. Aids, 19(8), 807–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sabin LL, Bachman DeSilva M, Gill CJ, Zhong L, Vian T, Xie W,… Gifford AL (2015). Improving adherence to antiretroviral therapy with triggered real-time text message reminders: The china adherence through technology study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999), 69(5), 551–559. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000651 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sankar A, Luborsky M, Schuman P, & Roberts G (2002). Adherence discourse among african-american women taking HAART. AIDS Care, 14(2), 203–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sherrard H, Struthers C, Kearns SA, Wells G, & Mesana T (2009). Using technology to create a medication safety net for cardiac surgery patients: A nurse-led randomized control trial. Canadian Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 19(3) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shubber Z, Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Vreeman R, Freitas M, Bock P,… Doherty M (2016). Patient-reported barriers to adherence to antiretroviral therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine, 13(11), e1002183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simoni JM, Huh D, Wilson IB, Shen J, Goggin K, Reynolds NR,… Liu H (2012). Racial/ethnic disparities in ART adherence in the united states: Findings from the MACH14 study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999), 60(5), 466–472. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825db0bd [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stringer KL, Azuero A, Ott C, Psaros C, Jagielski CH, Safren SA,… Kempf M (2019). Feasibility and acceptability of real-time antiretroviral adherence monitoring among depressed women living with HIV in the deep south of the US. AIDS and Behavior, 23(5), 1306–1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stumbo S, Wrubel J, & Johnson MO (2011). A qualitative study of HIV treatment adherence support from friends and family among same sex male couples. Psychology and Education, 2(4), 318–322. doi: 10.4236/psych.2011.24050 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thrasher AD, Earp JAL, Golin CE, & Zimmer CR (2008). Discrimination, distrust, and racial/ethnic disparities in antiretroviral therapy adherence among a national sample of HIV-infected patients. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 49(1), 84–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wood E, Hogg RS, Yip B, Harrigan PR, O’Shaughnessy MV, & Montaner JS (2003). Effect of medication adherence on survival of HIV-infected adults who start highly active antiretroviral therapy when the CD4 cell count is 0.200 to 0.350× 109 cells/L. Annals of Internal Medicine, 139(10), 810–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woodward EN, & Pantalone DW (2012). The role of social support and negative affect in medication adherence for HIV-infected men who have sex with men. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 23(5), 388–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wrubel J, Stumbo S, & Johnson MO (2008). Antiretroviral medication support practices among partners of men who have sex with men: A qualitative study. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 22(11), 851–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wrubel J, Stumbo S, & Johnson MO (2010). Male same-sex couple dynamics and received social support for HIV medication adherence. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27(4), 553–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]