Graphical abstract

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; LAMP, Loop-mediated isothermal amplification; IVD, in-vitro diagnosis; POC, point-of-care; RT-qPCR, real-time reverse transcriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction; Ct, threshold cycle; VOC, variants of concern; CRISPR, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats; NGS, next-generation sequencing

Keywords: Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) diagnosis, Emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants, Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP)

Abstract

Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) is widely used in detection of pathogenic microorganisms including SARS-CoV-2. However, the performance of LAMP assay needs further exploration in the emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants test. Here, we design serials of primers and select an optimal set for LAMP-based on SARS-CoV-2 N gene for a robust and visual assay in SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis. The limit of detectable template reaches 10 copies of N gene per 25 μL reaction at isothermal 58℃ within 40 min. Importantly, the primers for LAMP assay locate at 12 to 213 nt of N gene, a highly conservative region, which serves as a compatible test in emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. Comparison to a commercial qPCR assay, this LAMP assay exerts the high viability in diagnosis of 41 clinical samples. Our study optimizes an advantageous LAMP assay for colorimetric detection of SARS-CoV-2 and emerging variants, which is hopeful to be a promising test in COVID-19 surveillance.

1. Introduction

The outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) caused a pandemic coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) since late 2019. As of 19 December 2021, the number of COVID-19 patients has exceeded 273 million worldwide, and the cumulative number of deaths has been over 5.3 million (WHO, 2021). SARS-CoV-2 is a beta coronavirus of group with a whole-genome resemblance of over 96%, including 5′ untranslated region (UTR), S (Spike), E, M, N genes, replicase complex (orf1ab) 3′UTR, and other unspecified non-structural open reading frames (Zhou et al., 2020). At present, the most important countermeasures for preventing human-to-human transmission of SARS-CoV-2 are early identification, proper isolation, and follow-up of patients (West et al., 2020). To provide timely care and create a surveillance system to prevent the spread of COVID-19, the development of an on-site, rapid, and responsive diagnostic assay, especially in-vitro diagnosis (IVD), for SARS-CoV-2 is a top priority. Although the efforts on COVID-19 surveillance have been greatly made, emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants (eg. Alpha, Beta, and Delta variants), particularly the new variant Omicron, also known as B.1.1.529, has shown worrisome effects on this improvement (Karim and Karim, 2021, Yang et al., 2020). Unfortunately, there are rarely current point-of-care (POC) testing modality allows specific identification of SARS-CoV-2 variants.

SARS-CoV-2 infection is primarily diagnosed by reverse transcriptase quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) as the standard molecular diagnostic test in the clinical laboratory. To date, numerous kinds of methods by reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) assays have been developed soon after the genome sequence of SARS-CoV-2 was published, and they are now the preferred assay for detecting viral RNA (Chu et al., 2020, Corman et al., 2020). Undoubtedly, RT-qPCR assay in SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis with high sensitivity necessitates the extraction of viral RNA prior to the test, but the use of a precise thermal cycler instrument connected to a reliable source of electricity, and costs of expensive reagent along with extensive labor (Kudo et al., 2020). Furthermore, due to overwhelmed healthcare systems and lack of rapid test of samples with a risk of viral RNA degradation during sample transport to the laboratory, there is an increase of false-negative rate in SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis (Yelin et al., 2020). To control and track SARS-CoV-2 infections, it is urgent to establish a lean immediately applicable protocol that can be performed at the point-of-care, even in rural areas of developing countries where reliable energy, device, and technician may be inaccessible.

Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) is a fast and responsive DNA detection tool with fast procedures and simple equipment (Notomi et al., 2000), which has received high concern to be widely used in the field of pathogenic microorganisms such as Klebsiella pneumoniae (Nakano et al., 2015), Staphylococcus aureus (Hanaki et al., 2011), Ebola virus (Kurosaki et al., 2016a, Kurosaki et al., 2016b), and Zika virus (Kurosaki et al., 2017). The updating LAMP technology has been deployed for field surveillance in response to an early phase of COVID-19 outbreaks, the detection of SARS-CoV-2 by RT-LAMP assays were initially explored (Baek et al., 2020, Yan et al., 2020). However, as COVID-19 pandemic emphasizes rapidly adapted and deployed diagnostics in a variety of settings, the optimization of primers design and development of LAMP detection for SARS-CoV-2 and main variants require further investigation. In this study, we optimized and designed the primers for loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) based on SARS-CoV-2 N gene, aiming to develop a robust and visual assay in SARS-CoV-2 and emerging variants diagnosis.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Clinical samples

All 41 suspected COVID-19 patients were subjected to the tests including clinical examination, Computed Tomography (CT) according to the “pneumonia diagnosis protocol for novel coronavirus infection (trial version 5)” (the published guidelines released by the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China), and admitted in Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China from Jan 27 to 31, 2020. All nasopharyngeal swab samples were collected for RNA extraction and reverse-transcription to cDNA for further examination. The cDNA of clinical samples was stored at −80 °C until use.

2.2. Obtaining of SARS-CoV-2 N gene

The sequence of SARS-CoV-2 N gene is derived from NCBI GenBank database (28,274 to 29,533 nt in complete genome from Wuhan-Hu-1 strain, accession number: NC_045512.2.). The target gene was synthesized (GenScript Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) and then ligated to pcDNA3.1-HA vector (Addgene Inc, Watertown, MA, USA) to generate pcDNA3.1-N-HA plasmid. Subsequently, the pcDNA3.1-N-HA plasmid was transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α strain, cultured, and propagated in LB medium supplemented with ampicillin to achieve amplification. The pcDNA3.1-N-HA plasmid DNA was extracted, and DNA concentration was determined. The plasmid DNA carrying SARS-CoV-2 N gene was stored at 4 °C until use.

2.3. Preparation of standards

The mass concentration and total base pair (bp) number of the plasmid pcDNA3.1-N-HA carrying the SARS-CoV-2 N gene were determined. The plasmid DNA copy number was calculated according to the following formula: DNA copy number = DNA mass concentration/(Number of bp × Relative molecular mass of one bp) × 6.02 × 1023.

The solution of the calculated DNA copy number was subjected to 10-fold serial dilutions in ddH2O to the concentrations from 1 × 10 to 1 × 108 copies μL−1. Subsequently, the prepared standards were stored at 4 °C until use.

2.4. Design and synthesis of primers

According to the principle of the LAMP, one primer set contains three pairs of primers that can recognize six independent regions of the target sequence. Namely, inner primers pair: forward inner primer (FIP) and backward inner primer (BIP); outer primers pair: F3 primer and B3 primer; loop primer pair: loop primer forward (LF) and loop primer backward (BF). Six sets of primers were designed for LAMP targeting SARS-CoV-2 N gene using PrimerExplorer V5 software (Fujitsu Limited, Tokyo, Japan). Primers designed for detection of five kinds of coronavirus (CoV) N genes were used in reverse-transcription (RT)-PCR. The information of the primers is listed in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Information of designed primers in this study.

| Primer Setting | Primer Name | Sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|---|

| PS1 | PS1-F3 | CACCCGCAATCCTGCTAAC |

| PS1-B3 | CCAGCCATTCTAGCAGGAGA | |

| PS1-FIP | TGCTCCCTTCTGCGTAGAAGCAATGCTGCAATCGTGCTACA | |

| PS1-BIP | GGCGGCAGTCAAGCCTCTTCCCTACTGCTGCCTGGAGTT | |

| PS1-LF | GCAATGTTGTTCCTTGAGGAAGT | |

| PS1-LB | TTCCTCATCACGTAGTCGCAACAGT | |

| PS2 | PS2-F3 | CCAGAATGGAGAACGCAGTG |

| PS2-B3 | CCGTCACCACCACGAATT | |

| PS2-FIP | AGCGGTGAACCAAGACGCAGGGCGCGATCAAAACAACG | |

| PS2-BIP | AATTCCCTCGAGGACAAGGCGAGCTCTTCGGTAGTAGCCAA | |

| PS2-LF | TTATTGGGTAAACCTTGGGGC | |

| PS2-LB | TCCAATTAACACCAATAGCAGTCCA | |

| PS3 | PS3-F3 | CCAGAATGGAGAACGCAGTG |

| PS3-B3 | CCGTCACCACCACGAATT | |

| PS3-FIP | AGCGGTGAACCAAGACGCAGGGCGCGATCAAAACAACG | |

| PS3-BIP | AATTCCCTCGAGGACAAGGCGAGCTCTTCGGTAGTAGCCAA | |

| PS3-LF | ATTATTGGGTAAACCTTGGGGC | |

| PS3-LB | CCAATTAACACCAATAGCAGTCCA | |

| PS4 | PS4-F3 | AGATCACATTGGCACCCG |

| PS4-B3 | CCATTGCCAGCCATTCTAGC | |

| PS4-FIP | TGCTCCCTTCTGCGTAGAAGCCAATGCTGCAATCGTGCTAC | |

| PS4-BIP | GGCGGCAGTCAAGCCTCTTCCCTACTGCTGCCTGGAGTT | |

| PS4-LF | GCAATGTTGTTCCTTGAGGAAGTT | |

| PS4-LB | GTTCCTCATCACGTAGTCGCAACA | |

| PS5 | PS5-F3 | AGATCACATTGGCACCCG |

| PS5-B3 | CCATTGCCAGCCATTCTAGC | |

| PS5-FIP | TGCTCCCTTCTGCGTAGAAGCCAATGCTGCAATCGTGCTAC | |

| PS5-BIP | GGCGGCAGTCAAGCCTCTTCCCTACTGCTGCCTGGAGTT | |

| PS5-LF | GGCAATGTTGTTCCTTGAGGAAGTT | |

| PS5-LB | GTTCCTCATCACGTAGTCGCAACA | |

| PS6 | PS6-F3 | TGGACCCCAAAATCAGCG |

| PS6-B3 | GCCTTGTCCTCGAGGGAAT | |

| PS6-FIP | CCACTGCGTTCTCCATTCTGGTAAATGCACCCCGCATTACG | |

| PS6-BIP | CGCGATCAAAACAACGTCGGCCCTTGCCATGTTGAGTGAGA | |

| PS6-LF | TTGAATCTGAGGGTCCACCA | |

| PS6-LB | TACCCAATAATACTGCGTCTTGGT | |

| PCR for CoV N genes | HCoV-OC43-F | ATGTCTTTTACTCCTGGTAAGCAATCCA |

| HCoV-OC43-B | TTATATTTCTGAGGTGTCTTCAGTAAAGGGC | |

| HCoV-NL63-F | ATGGCTAGTGTAAATTGGGCCG | |

| HCoV-NL63-B | TTAATGCAAAACCTCGTTGACAATTTCT | |

| GX_P2V-F | ATGTCTGATAATGGACCCCAAA | |

| GX_P2V-B | TACCCAATAATACTGCGTCTTGGT | |

| SADS-CoV-F | ATGGCCACTGTTAATTGGGGTG | |

| SADS-CoV-B | CTAATTAATAATCTCATCCACCATCTCAACCTCC | |

| SARS-CoV-2-F | ATGTCTGATAATGGACCCCAAAATC | |

| SARS-CoV-2-B | TTAGGCCTGAGTTGAGTCAGCACTG |

PS: Primer Setting; FIP: Forward Inner Primer; BIP: Backward Inner Primer; LF: Loop Primer Forward; LB: Loop Primer Backward; F3: F3 primer; B3: B3 primer; F: Forward; B: Backward; HCoV, human coronavirus; SADS, swine acute diarrhea syndrome.

The primers were synthesized by Tsingke Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Beijing, China). The dried primer DNA pellets were dissolved in sterile RNase-free deionized water to a concentration of 100 μM for storage at −20 °C.

2.5. Determination and optimization of LAMP reaction system

The LAMP reaction system with a 25 μL of volume contains 1 μL of Bsm DNA polymerase (Lot#00892391), 2.5 μL of Bsm 10 × Buffer (Lot#00872639) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 4 μL of dNTP (2.5 mM) (Lot#AJ11753A) (Takara Biomedical Tech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China), 4 μL mixed primer solution [F3 (20 μM) and B3 (20 μM): 0.4 μL each; FIP (20 μM) and BIP (20 μM), LF (20 μM) and BF-N1 (20 μM): 0.8 μL each], 1 μL DNA template, and rest of ddH2O to make up to 25 μL. The LAMP reaction was performed in a DNA amplification instrument. The DNA products were amplified with 1 μL of DNA template at different concentrations ranging from 101 to 107 copies μL−1 at temperature gradients (55 °C, 58 °C, 60 °C, 62 °C) for 30 min or at time gradients (0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45 min), and then separated by agarose gel electrophoresis. Relative quantity of each DNA product was analyzed by ImageJ software. For each reaction, at least three independent replicates were performed.

In a colorimetric LAMP reaction system, an additional 1 μL of 625 μM Calcein (Lot#G424BA0029, purchased from Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) and 1 μL of 7.5 mM MnCl2 (Lot#MKCJ8390, purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was supplied, and then incubated in an optimal condition at 58 °C for 40 min in either a PCR device (Lot#8110953843) (Eastwin Scientific Equipments Inc; Suzhou, China) or a constant temperature water bath (DK-8D) (Everone Precision Instrument Co., Ltd; Shanghai, China). The color change from orange to green was observed in a positive reaction.

2.6. Sensitivity and specificity of LAMP assay

A serial of 10-fold dilutions of DNA standards ranging from 1 × 10 to 1 × 107 copies μL−1 was prepared. The sensitivity of LAMP assay was accessed by adding 1 μL of DNA template in the 25 μL of volume reaction at 58 °C for 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45 min, respectively. The positive reactions were observed by agarose gel electrophoresis or color change.

The specificity of the LAMP assay was first examined by Xho I restriction endonuclease (Takara Biomedical Tech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) at target DNA product. Then, several kinds of common pathogenic microorganism DNA were prepared for LAMP assay. The genome DNAs of ADV-3 from our previous study (Yan et al., 2021), Streptococcus pneumonia, and Staphylococcus aureus (obtained from CCTCC, Wuhan, China) was extracted, while genome RNA of H3N2 (HongKong/498/97 strain) from our previous study (Ge et al., 2017) was extracted and then reverse transcribed into cDNA for detection. Four kinds of cDNA samples of HCoV-OC43, HCoV-NL63 (kindly provided by Dr Jincun Zhao, Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, China), GX_P2V, and SDAS-CoV (kindly provided by Dr Huahan Fan, Beijing University of Chemical Technology, Beijing, China) were collected. Then, 1 × 104 copies of each DNA sample were subjected to 25 μL of volume reaction and observed by agarose gel electrophoresis or visual color change.

2.7. Evaluation of LAMP assay in SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis using clinical samples

The performance of LAMP assay in SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis was evaluated in 41 suspected COVID-19 patients admitted in Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China. A comparison between LAMP assay and a commercial SARS-CoV-2 RT-qPCR kit (Daan Gene Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China) was performed. In each reaction, 2 μL of clinical specimen cDNA, positive or negative DNA controls were mixed for LAMP detection or qPCR in a Light Cycle480 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). The positive samples were counted by visual color change in LAMP detection while cycle threshold (Ct) value in qPCR assay. The concordance rate between both assays was calculated by the formula: Concordance rate = Number of consistent results by both assays/Total number × 100%.

2.8. Statistical analysis

In a comparison of two assays, the Chi-square (χ2) test was used for the difference between two groups of enumeration data by SPSS software version 25.0 (IBM Corp.; Armonk, NY, USA). A P value < 0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Primer design for LAMP assay

LAMP is one of the most concerned point-of-care testing (POCT) assays in rapid SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis (Chaouch, 2021). In the principle of the LAMP, one set of primers contains three pairs of primers, namely inner primers pair, outer primers pair, and loop primer pair, which recognize six independent regions of the target sequence (Fig. 1 A). SARS-CoV-2 N gene is considered to be the main positive component in of SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid detection (Zhang et al., 2020). Six sets of primers were designed for LAMP targeting SARS-CoV-2 N gene using Primer Explorer V5 software in different regions. Two sets of primers (PS2 and 3; PS4 and 5) shared the same inner and outer primers but different loop primers, while PS1 and PS6 resided at 441–635 nt and 12–213 nt of the N gene, respectively (Table 1 and Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Primers design for LAMP assay. (A) Principle of LAMP primers design. A set of primers contain inner primer pair (FIP: Forward Inner Primer; BIP: Backward Inner Primer), loop primer pair (LF: Loop Primer Forward; LB: Loop Primer Backward), and outer primer pair (F3: F3 primer; B3: B3 primer). Six regions were displayed as a color box. F1c means complementary sequence of F1. Primers Setting, PS. (B) Location of each set of primers in SARS-CoV-2 N gene. Six sets of primers were indicated as PS1 to PS2, respectively.

3.2. Optimization of primers in LAMP reaction system

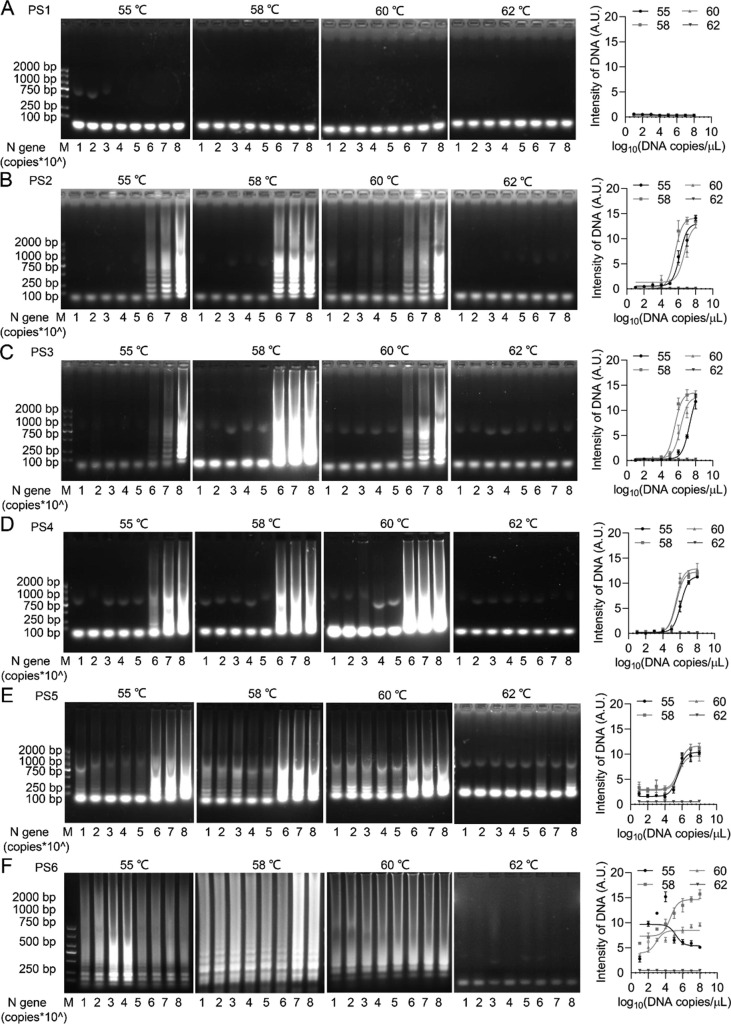

To investigate the sensitivity of LAMP assay with designed primers, a serial dilution of SARS-CoV-2 N gene DNA standards ranging from 100 to 108 copies μL−1 were used in 25 μL of volume reaction for 30 min at different temperatures. Except for PS1, PS2 to PS5 primers were engaged to generate an obvious typical S-shaped DNA amplification curve at 55, 58, and 60 °C, whereas the detectable template concentrations were limited to 105 copies μL−1 (Fig. 2 A-E), suggesting low sensitivity of LAMP reaction with PS2 to PS5. PS6 primers were engaged to an obvious S-shaped DNA amplification curve at 58 °C with detectable template concentration reached to 101 copies μL−1 (Fig. 2F), indicating the optimal primers in LAMP reaction.

Fig. 2.

Determination of LAMP reaction system. A serial dilution of SARS-CoV-2 N gene DNA standards ranged from 100 to 108 copies μL−1 (1 μL each) were added in 25 μL of volume reaction for 30 min at different temperatures. The DNA products generated from indicated primer: PS1 (A), PS2 (B), PS3 (C), PS4 (D), PS5 (E), PS6 (F), were observed and quantified. M, DNA marker. A.U., Arbitrary Unit.

3.3. Specificity of LAMP assay for SARS-CoV-2 and variants

To further identify the sensitivity of LAMP assay with SP6 primers, the reaction was performed at indicated time at 58 °C. The obvious S-shaped DNA amplification curves were observed with template concentrations from 107 to 101 copies μL−1 within 20 min, and entered a plateau phase within 30 to 45 min (Fig. 3 A), suggesting the assay is sensitive and rapid.

Fig. 3.

Sensitivity and specificity of the developed LAMP assay. (A) One μL of DNA standards ranged from 1 × 10 to 1 × 107 copies μL−1 were added in the 25 μL of volume reaction at 58 °C for indicated time, respectively. The DNA products were observed and quantified. A.U., Arbitrary Unit. (B) Specific sequence of amplificated DNA unit in LAMP by SP6 primers. The location of restriction enzyme site was indicated. (C) The DNA products were digested by an Xho I restriction endonuclease. (D) Each DNA sample was subjected to 25 μL of volume reaction and observed by agarose gel electrophoresis. M, DNA marker. 1. ADV-3 DNA, 2. Streptococcus pneumonia DNA, 3. Staphylococcus aureus DNA, 4. SARS-CoV-2 N gene, 5. H3N2 cDNA. (E) Each viral cDNA sample (10,000 copies) was subjected to 25 μL of volume LAMP reaction and observed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Various coronavirus N genes were amplified by PCR with specific primers. M, DNA marker. 1. HCoV-OC43, 2. HCoV-NL63, 3. GX_P2V, 4. SADS-CoV, 5. SARS-CoV-2. (F) The alignment of amplification of target region by SP6 primers of LAMP assay in SARS-CoV-2 N gene from various variants. The sequences of Alpha variant: B.1.1.7; Beta variant: B.1.351; Gamma variant: P1; Delta variant: B.1.617.2 were released from the public NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The sequences of Omicron variant: B.1.1.529 were released from the public GISAID database (https://www.gisaid.org/).

Considering the specific sequence of amplificated DNA unit in LAMP, the DNA products with SP6 primers were digested by a distinct Xho I restriction endonuclease (Fig. 3B). The amplified DNA by SP6 primers was significantly reduced by Xho I digestion (Fig. 3C). Then, several kinds of commonly respiratory pathogenic microorganism DNA were prepared for LAMP assay. The LAMP reaction system displayed a strong positive detection on SARS-CoV-2 N gene as expected, but showed no cross action on neither ADV-3, Streptococcus pneumonia, and Staphylococcus aureus genomic DNA, nor H3N2 cDNA (Fig. 3D). Similarly, in the presence of various N genes of coronaviruses amplificated by specific PCR primers, an obvious positive LAMP assay was shown in the detection of cDNA of SARS-CoV-2, but not in common human coronavirus HCoV-OC43 and HCoV-NL63, or pangolin coronavirus GX_P2V, or swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus SADS-CoV (Fig. 3E), implying the specificity of DNA amplification of the LAMP assay.

Emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants have shown worrisome effects on viral identification and require rapidly adapted and deployed diagnostics in a variety of settings (Kumar et al., 2021). The coverage of the developed LAMP assay on detection of SARS-CoV-2 variants was further explored. The alignment of target region of N gene from SARS-CoV-2 variants exhibited a highly conservative sequence in typical variants including B.1.1.7 (Alpha), B.1.351 (Beta), P1 (Gamma), B.1.617.2 (Delta), and B.1.1.529 (Omicron) substrains (Fig. 3F). Of note, there was over 99.5% similarity of the sequence from the N gene of SARS-CoV-2B.1.617.2 and B.1.1.529 variants to the target region in the LAMP assay, respectively (Fig. 3F), suggesting a compatible detection on main emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants by this LAMP assay.

3.4. Visual detection of the LAMP assay

To develop a visual detection of SARS-CoV-2 LAMP for portable application, a metal ion indicator, Calcein, of which the color was modulated by manganese chloride (MnCl2) from orange to green was introduced in the reaction system (Fig. 4 A). The reaction gave a clear color change from orange to green for 40 min in the samples with template concentrations from 105 to 101 copies μL−1 (Fig. 4B). In addition, the colorimetric LAMP assay was effectively operated in either PCR device (Fig. 4C and D) or water bath (Fig. 4E and F), indicating a convenient and sensitive assay regardless of isothermal heating instruments.

Fig. 4.

The colorimetric LAMP reaction system. (A) The schematic diagram for color change of MnCl2-mediated Calcein in the LAMP reaction system. (B) The colorimetric LAMP was performed at 58 °C for 40 min with the color of Calcein from orange to green after a positive reaction. (C-F) The colorimetric LAMP was performed at 58 °C for 40 min by PCR device heating (C) with positive reaction (D), or Water bath heating (E) with positive reaction (F).

3.5. Evaluation of LAMP assay in clinical SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis

To evaluate the clinical diagnostic effect of the LAMP assay, 41 clinical samples of nasopharyngeal swabs from suspected COVID-19 patients were tested in comparison to a commercial qPCR assay. Of these samples, 23 and 18 were detected as SARS-CoV-2 positive and negative by LAMP assay, respectively (Fig. 5 A and Table 2 ). Additionally, the colorimetric LAMP displayed a specific positive reaction to DNA samples of SARS-CoV-2 N gene, but not to commonly respiratory pathogens (Fig. 5B) or other kinds of coronaviruses (Fig. 5C). In comparison, 21 and 20 were detected as SARS-CoV-2 positive and negative by qPCR assay, respectively (Fig. 5D and Table 2). The LAMP assay behaved a comparative positive rate in SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis to qPCR assay (Fig. 5E and Table 3 ). Notably, two samples were detected as positive by LAMP assay but negative by qPCR. The concordance rate between both assays was 95.1% (Table 3), demonstrating LAMP assay presents a reliable detection and matchable viability to qPCR for SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis.

Fig. 5.

A comparison of LAMP and qPCR assay in clinical suspected SARS-CoV-2 patients. (A) The visual LAMP assay in 41 samples from suspected SARS-CoV-2 patients and controls. The change of green in labeled samples was tested positive SARS-CoV-2. (B) DNA samples were subjected to 25 μL of volume reaction. The positive test was observed by a color change from orange to green. M, DNA marker. 1. ADV-3 DNA, 2. Streptococcus pneumonia DNA, 3. Staphylococcus aureus DNA, 4. SARS-CoV-2 N gene, 5. H3N2 cDNA. (C) Each viral cDNA sample (10,000 copies) was subjected to 25 μL of volume LAMP reaction and observed by color change from orange to green. 1. HCoV-OC43, 2. HCoV-NL63, 3. GX_P2V, 4. SADS-CoV, 5. SARS-CoV-2. (D) The melting curve of each sample in qPCR analysis. The positive test was cut-off with the threshold cycle (Ct) values over 32. The negative and positive controls were indicated by green and blue arrow, respectively. (E) The results of negative (in gray) and positive (in red) rates were displayed by LAMP and qPCR assays, respectively.

Table 2.

Detection of 41 clinical samples in qPCR and LAMP assays.

| Sample name | qPCR (Ct value) | LAMP (color change) | Positive (qPCR/LAMP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25.75 | Green | +/+ |

| 2 | 32.08 | Orange | −/− |

| 3 | 32.31 | Orange | −/− |

| 4 | 29.34 | Green | +/+ |

| 5 | 38.46 | Orange | −/− |

| 6 | 29.98 | Green | +/+ |

| 7 | 29.76 | Green | +/+ |

| 8 | 31.99 | Green | +/+ |

| 9 | 31.08 | Green | +/+ |

| 10 | 30.33 | Green | +/+ |

| 11 | 36.49 | Orange | −/− |

| 12 | 40.00 | Orange | −/− |

| 13 | 29.32 | Green | +/+ |

| 14 | 29.84 | Green | +/+ |

| 15 | 30.62 | Green | +/+ |

| 16 | 29.27 | Green | +/+ |

| 17 | 31.22 | Green | +/+ |

| 18 | 39.27 | Orange | −/− |

| 19 | 32.08 | Green | −/+ |

| 20 | 29.44 | Green | +/+ |

| 21 | 29.93 | Green | +/+ |

| 22 | 26.45 | Green | +/+ |

| 23 | 30.83 | Green | +/+ |

| 24 | 26.55 | Green | +/+ |

| 25 | 34.22 | Orange | −/− |

| 26 | 40.00 | Orange | −/− |

| 27 | 39.52 | Orange | −/− |

| 28 | 38.15 | Orange | −/− |

| 29 | 39.56 | Orange | −/− |

| 30 | 36.64 | Orange | −/− |

| 31 | 40.00 | Orange | −/− |

| 32 | 35.32 | Orange | −/− |

| 33 | 22.05 | Green | +/+ |

| 34 | 26.58 | Green | +/+ |

| 35 | 32.17 | Green | −/+ |

| 36 | 40.00 | Orange | −/− |

| 37 | 37.05 | Orange | −/− |

| 38 | 32.29 | Orange | −/− |

| 39 | 24.78 | Green | +/+ |

| 40 | 23.62 | Green | +/+ |

| 41 | 37.62 | Orange | −/− |

Ct, threshold cycle; +, positive; −, negative; qPCR positive: cut-off with Ct value > 32.00; LAMP positive: green color.

Table 3.

Comparison of qPCR and LAMP tests for SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosis in suspected patients.

| SARS-CoV-2 N gene | Negative (N) | Positive (N) | Positive Rate (%) | Total (N) | Concordance rate (%) | χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAMP | 18 | 23 | 56.1 | 41 | 95.1 | 0.658 |

| qPCR | 20 | 21 | 48.8 |

N, number of cases; χ2, Chi-square test for the difference between LAMP and qPCR assays. P < 0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

4. Discussion

In recent years, the LAMP technology has been recognized by many aspects in infectious disease analysis and diagnosis, owing to no need of high temperature denaturation of the template and repeated heating and cooling steps. The LAMP operation process is simple, and the amplification is rapid and efficient, which is suitable for testing in the cases of imperfect experimental equipment, and wide use in the grassroots, laboratories with poor experimental conditions and on-site use (Wong et al., 2018). Now, the accessible nature of the nucleic acid test by LAMP extends its potential to make a huge impact in the fight against COVID-19. Compared to RT-qPCR, LAMP has been developed to detect SARS-CoV-2 RNA targeting nucleocapsid (N), open reading frame 1ab (ORF1ab), and spike (S) gene, demonstrating an excellent agreement with other SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid amplification methods (Bulterys et al., 2020). Nevertheless, emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants commonly cause genetic mutations, which comes to the potential impacts on performance genetic variants evading detection by specific viral diagnostic tests (Thompson et al., 2021). Unfortunately, the lack of current point-of-care (POC) testing modality hardly allows specific identification on SARS-CoV-2 variants.

In this study, the optimization of the primers and LAMP assay was developed for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 and emerging variants. The optimal conditions at isothermal 58℃ within 40 min of LAMP reaction system were established among six sets of primers targeting SARS-CoV-2 N gene. Although similar studies reveal compatible conditions of LAMP assay for SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid detection, the developed LAMP assay here reached a limit of detectable template of 10 to100 copies in each reaction within 40 min, suggesting a superior sensitivity and timesaving to previously reported 100 to 1000 copies per reaction within 40 to 60 min (Baek et al., 2020, Lu et al., 2020, Pang et al., 2020, Quino et al., 2021). It could be explained that the optimal primers targeting at 12–213 nt of SARS-CoV-2 N gene contributed to the improvement of the LAMP assay. More importantly, their specific sequences of primers were highly conservative according to the alignments of 12–213 nt region of N gene pf main emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants, behaving perfect compatibility on specific identification on SARS-CoV-2 variants.

As the COVID-19 epidemic, the great efforts have been made to adopt the methods of test for SARS-CoV-2 variants. FnCas9-based CRISPR and novel SHERLOCK diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 variants arise rapid test in COVID-19 surveillance (de Puig et al., 2021, Kumar et al., 2021). Although multiply tests to variants of concern (VOC), including Delta and Omicron, are now being developed and utilized such as next-generation sequencing (NGS), it is neither practical nor sustainable for most POC tests. Thus, the rapid identification of viral nucleic acids using technologies leveraging PCR or isothermal amplification targeting beyond S gene is encouraged (Karim and Karim, 2021, Thomas et al., 2021). However, as no specialists are needed to operate it and results are easy to interpret, LAMP assay is still the primary fast test SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosis. Next, we accessed the rapid and visual detection with the introduction of manganese chloride-calcein, a typical metal ion indicator in the LAMP reaction system (Tomita et al., 2008). In this colorimetric LAMP reaction, the precisely visual color change from orange to green was observed for 40 min at a limitation as many as 10 copies template. Of note, the visual LAMP assay could be well performed regardless of isothermal heating instruments, which is reliably carried out the on-site use with imperfect experimental equipment and poor experimental conditions.

In comparison to a commercial qPCR assay using 41 clinical samples, the LAMP assay was tested a comparative positive rate in SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis to qPCR assay with no cross-reactivity with nucleic acid from other four human respiratory microorganisms, including ADV-3, Streptococcus pneumonia, Staphylococcus aureus, and H3N2, revealing that it possesses a high sensitivity and specificity in SARS-CoV-2 detection in nasopharyngeal swabs samples. Generally, the nasopharyngeal swabs samples were primary selection for the early diagnosis of COVID-19, especially for mild and asymptomatic patients, but its false negative rate was usually reported to be lower than that in other types of clinical specimens such as sputum (Wang et al., 2020). The mean viral load in nasal swabs of COVID-19 patients is 1.4 × 106 copies/mL (Lu et al., 2020), our developed LAMP assay with a detectable viral cDNA template of 10,000 copies (equal to 4 × 105 copies/mL) is competent for the early SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis combined with an easy sampling of nasal swab specimens. However, there are still some procedures in this LAMP assay to be improved, eg. the nucleic acid extraction-free protocol before LAMP (Lalli et al., 2021), one-step reverse transcription (RT) with LAMP (Li et al., 2021, Wong Tzeling et al., 2021), or the LAMP-based quantitative detection of SARS-CoV-2 (González-González et al., 2021), which polishes the developed LAMP reaction system and facilitates the generalization of the simple, fast, and efficient in-vitro diagnosis.

5. Conclusions

In sum, we optimized primers targeting SARS-CoV-2 N gene and established a robust and visual LAMP reaction system at isothermal 58℃ within 40 min. The superiority of the LAMP assay exerted excellent compatibility on specific detection on SARS-CoV-2 variants and a limit of detectable template of 10 copies regardless of isothermal heating instruments. We believe the developed LAMP assay presents matchable effectiveness to qPCR for SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosis, which is expected to be performed at the point-of-care (POC) in control of COVID-19 pandemic.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Zhen Luo: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Chunhong Ye: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology. Heng Xiao: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology. Jialing Yin: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology. Yicong Liang: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology. Zhihui Ruan: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology. Danju Luo: Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation. Daolong Gao: Investigation, Resources, Validation. Qiuping Tan: Investigation, Resources, Validation. Yongkui Li: Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources. Qiwei Zhang: Investigation, Resources, Validation. Weiyong Liu: Conceptualization, Resources, Validation, Supervision. Jianguo Wu: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We frankly thank patients, researchers, and clinical staff who provided significant contributions to this study. We also appreciate Dr Jincun Zhao of Guangzhou Medical University for kindly providing HCoV-OC43 and HCoV-NL63 cDNA, Dr Huahan Fan of Beijing University of Chemical Technology for providing GX_P2V and SDAS-CoV cDNA, and Dr Junhua Li of BGI-Shenzhen, Shenzhen, China, for the assistance of sequence analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant.

Fundings

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [32070148 to ZL]; Guangzhou Basic Research Program - Basic and Applied Basic Research Project [202102020260 to ZL].

Ethical approval

Research involving human subjects complied with all relevant national regulations, institutional policies and is in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013), and has been approved by the Ethics Committee and Institutional Review Board of the Tongji Hospital of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (file no. TJ-IRB20200201). Written informed consent was obtained from each enrolled patient.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO), 2021. COVID-19 Weekly Epidemiological Update, Edition 71.

- Baek Y.H., Um J., Antigua K.J.C., Park J.-H., Kim Y., Oh S., Kim Y.-i., Choi W.-S., Kim S.G., Jeong J.H., Chin B.S., Nicolas H.D.G., Ahn J.-Y., Shin K.S., Choi Y.K., Park J.-S., Song M.-S. Development of a reverse transcription-loop-mediated isothermal amplification as a rapid early-detection method for novel SARS-CoV-2. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):998–1007. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1756698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulterys P.L., Garamani N., Stevens B., Sahoo M.K., Huang C., Hogan C.A., Zehnder J., Pinsky B.A. Comparison of a laboratory-developed test targeting the envelope gene with three nucleic acid amplification tests for detection of SARS-CoV-2. J. Clin. Virol. 2020;129:104427. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaouch M. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP): An effective molecular point-of-care technique for the rapid diagnosis of coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Rev. Med. Virol. 2021;31(6) doi: 10.1002/rmv.v31.610.1002/rmv.2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu D.K.W., Pan Y., Cheng S.M.S., Hui K.P.Y., Krishnan P., Liu Y., Ng D.Y.M., Wan C.K.C., Yang P., Wang Q., Peiris M., Poon L.L.M. Molecular diagnosis of a novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) causing an outbreak of pneumonia. Clin. Chem. 2020;66(4):549–555. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/hvaa029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corman V.M., Landt O., Kaiser M., Molenkamp R., Meijer A., Chu D.K.W., Bleicker T., Brunink S., Schneider J., Schmidt M.L., Mulders D., Haagmans B.L., van der Veer B., van den Brink S., Wijsman L., Goderski G., Romette J.L., Ellis J., Zambon M., Peiris M., Goossens H., Reusken C., Koopmans M.P.G., Drosten C. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Euro. Surveill. 2020;25 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Puig H., Lee R.A., Najjar D., Tan X., Soenksen L.R., Angenent-Mari N.M., Donghia N.M., Weckman N.E., Ory A., Ng C.F., Nguyen P.Q., Mao A.S., Ferrante T.C., Lansberry G., Sallum H., Niemi J., Collins J.J. Minimally instrumented SHERLOCK (miSHERLOCK) for CRISPR-based point-of-care diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 and emerging variants. Sci. Adv. 2021;7(32) doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abh2944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge M., Luo Z., Qiao Z., Zhou Y., Cheng X., Geng Q., Cai Y., Wan P., Xiong Y., Liu F., Wu K., Liu Y., Wu J. HERP Binds TBK1 To activate innate immunity and repress virus replication in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. J. Immunol. 2017;199(9):3280–3292. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-González E., Lara-Mayorga I.M., Rodríguez-Sánchez I.P., Zhang Y.S., Martínez-Chapa S.O., Santiago G.-d., Alvarez M.M. Colorimetric loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) for cost-effective and quantitative detection of SARS-CoV-2: the change in color in LAMP-based assays quantitatively correlates with viral copy number. Anal. Methods. 2021;13(2):169–178. doi: 10.1039/d0ay01658f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanaki K.-I., Sekiguchi J.-I., Shimada K., Sato A., Watari H., Kojima T., Miyoshi-Akiyama T., Kirikae T. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification assays for identification of antiseptic- and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Microbiol. Methods. 2011;84(2):251–254. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karim S.S.A., Karim Q.A. Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variant: a new chapter in the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021;398(10317):2126–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02758-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo E., Israelow B., Vogels C.B.F., Lu P., Wyllie A.L., Tokuyama M., Venkataraman A., Brackney D.E., Ott I.M., Petrone M.E., Earnest R., Lapidus S., Muenker M.C., Moore A.J., Casanovas-Massana A., Yale I.R.T., Omer S.B., Dela Cruz C.S., Farhadian S.F., Ko A.I., Grubaugh N.D., Iwasaki A. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA by multiplex RT-qPCR. PLoS Biol. 2020;18 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M., Gulati S., Ansari A.H., Phutela R., Acharya S., Azhar M., Murthy J., Kathpalia P., Kanakan A., Maurya R., Vasudevan J.S., S A., Pandey R., Maiti S., Chakraborty D. FnCas9-based CRISPR diagnostic for rapid and accurate detection of major SARS-CoV-2 variants on a paper strip. Elife. 2021;10 doi: 10.7554/eLife.67130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosaki Y., Magassouba N., Bah H.A., Soropogui B., Doré A., Kourouma F., Cherif M.S., Keita S., Yasuda J. Deployment of a reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification test for Ebola virus surveillance in remote areas in Guinea. J. Infect. Dis. 2016;214(suppl 3):S229–S233. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosaki Y., Magassouba N., Oloniniyi O.K., Cherif M.S., Sakabe S., Takada A., Hirayama K., Yasuda J. Development and evaluation of reverse transcription-loop-mediated isothermal amplification (RT-LAMP) assay coupled with a portable device for rapid diagnosis of ebola virus disease in Guinea. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosaki Y., Martins D.B.G., Kimura M., Catena A.D.S., Borba M., Mattos S.D.S., Abe H., Yoshikawa R., de Lima Filho J.L., Yasuda J. Development and evaluation of a rapid molecular diagnostic test for Zika virus infection by reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:13503. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13836-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalli M.A., Langmade J.S., Chen X., Fronick C.C., Sawyer C.S., Burcea L.C., Wilkinson M.N., Fulton R.S., Heinz M., Buchser W.J., Head R.D., Mitra R.D., Milbrandt J. Rapid and extraction-free detection of SARS-CoV-2 from saliva by colorimetric reverse-transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Clin. Chem. 2021;67(2):415–424. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/hvaa267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Hu X., Wang X., Yang J., Zhang L., Deng Q., Zhang X., Wang Z., Hou T., Li S. A novel One-pot rapid diagnostic technology for COVID-19. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2021;1154:338310. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2021.338310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R., Wu X., Wan Z., Li Y., Jin X., Zhang C. A novel reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification method for rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21 doi: 10.3390/ijms21082826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano R., Nakano A., Ishii Y., Ubagai T., Kikuchi-Ueda T., Kikuchi H., Tansho-Nagakawa S., Kamoshida G.o., Mu X., Ono Y. Rapid detection of the Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) gene by loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) J Infect Chemother. 2015;21(3):202–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notomi T., Okayama H., Masubuchi H., Yonekawa T., Watanabe K., Amino N., Hase T. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:E63. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.12.e63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang B.o., Xu J., Liu Y., Peng H., Feng W., Cao Y., Wu J., Xiao H., Pabbaraju K., Tipples G., Joyce M.A., Saffran H.A., Tyrrell D.L., Zhang H., Le X.C. Isothermal amplification and ambient visualization in a single tube for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 using loop-mediated amplification and CRISPR technology. Anal. Chem. 2020;92(24):16204–16212. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.0c04047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quino W., Flores-Leon D., Caro-Castro J., Hurtado C.V., Silva I., Gavilan R.G. Evaluation of reverse transcription-loop-mediated isothermal amplification for rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:24234. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-03623-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas E., Delabat S., Carattini Y.L., Andrews D.M. SARS-CoV-2 and variant diagnostic testing approaches in the United States. Viruses. 2021;13(12):2492. doi: 10.3390/v13122492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson C.N., Hughes S., Ngai S., Baumgartner J., Wang J.C., McGibbon E., Devinney K., Luoma E., Bertolino D., Hwang C., Kepler K., Del Castillo C., Hopkins M., Lee H., DeVito A.K., Rakeman J.L. Rapid emergence and epidemiologic characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 B.1.526 variant – New York City, New York, January 1-April 5, 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2021;70:712–716. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7019e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita N., Mori Y., Kanda H., Notomi T. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) of gene sequences and simple visual detection of products. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3(5):877–882. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Xu Y., Gao R., Lu R., Han K., Wu G., Tan W. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens. JAMA. 2020;323:1843–1844. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West R., Michie S., Rubin G.J., Amlôt R. Applying principles of behaviour change to reduce SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020;4(5):451–459. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-0887-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong Tzeling J.M., Engku Nur Syafirah E.A.R., Irekeola A.A., Yusof W., Aminuddin Baki N.N., Zueter A., Harun A., Chan Y.Y. One-step, multiplex, dual-function oligonucleotide of loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay for the detection of pathogenic Burkholderia pseudomallei. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2021;1171:338682. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2021.338682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong Y.-P., Othman S., Lau Y.-L., Radu S., Chee H.-Y. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP): a versatile technique for detection of micro-organisms. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2018;124(3):626–643. doi: 10.1111/jam.13647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan C., Cui J., Huang L., Du B., Chen L., Xue G., Li S., Zhang W., Zhao L., Sun Y., Yao H., Li N., Zhao H., Feng Y., Liu S., Zhang Q., Liu D., Yuan J. Rapid and visual detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) by a reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020;26(6):773–779. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y., Jing S., Feng L., Zhang J., Zeng Z., Li M., Zhao S., Ou J., Lan W., Guan W., Wu X., Wu J., Seto D., Zhang Q. Construction and characterization of a novel recombinant attenuated and replication-deficient candidate human adenovirus type 3 vaccine: “Adenovirus Vaccine Within an Adenovirus Vector”. Virol. Sin. 2021;36(3):354–364. doi: 10.1007/s12250-020-00234-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H.-C., Chen C.-H., Wang J.-H., Liao H.-C., Yang C.-T., Chen C.-W., Lin Y.-C., Kao C.-H., Lu M.-Y., Liao J.C. Analysis of genomic distributions of SARS-CoV-2 reveals a dominant strain type with strong allelic associations. Proc. Natl. Acad Sci. U.S.A. 2020;117(48):30679–30686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2007840117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yelin I., Aharony N., Tamar E.S., Argoetti A., Messer E., Berenbaum D., Shafran E., Kuzli A., Gandali N., Shkedi O., Hashimshony T., Mandel-Gutfreund Y., Halberthal M., Geffen Y., Szwarcwort-Cohen M., Kishony R. Evaluation of COVID-19 RT-qPCR test in multi sample pools. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020;71(16):2073–2078. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Li M., Zhang B., Chen T., Lv D., Xia P., Sun Z., Shentu X., Chen H., Li L., Qian W. The N gene of SARS-CoV-2 was the main positive component in repositive samples from a cohort of COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, China. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2020;511:291–297. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou P., Yang X.-L., Wang X.-G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., Si H.-R., Zhu Y., Li B., Huang C.-L., Chen H.-D., Chen J., Luo Y., Guo H., Jiang R.-D., Liu M.-Q., Chen Y., Shen X.-R., Wang X.i., Zheng X.-S., Zhao K., Chen Q.-J., Deng F., Liu L.-L., Yan B., Zhan F.-X., Wang Y.-Y., Xiao G.-F., Shi Z.-L. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]