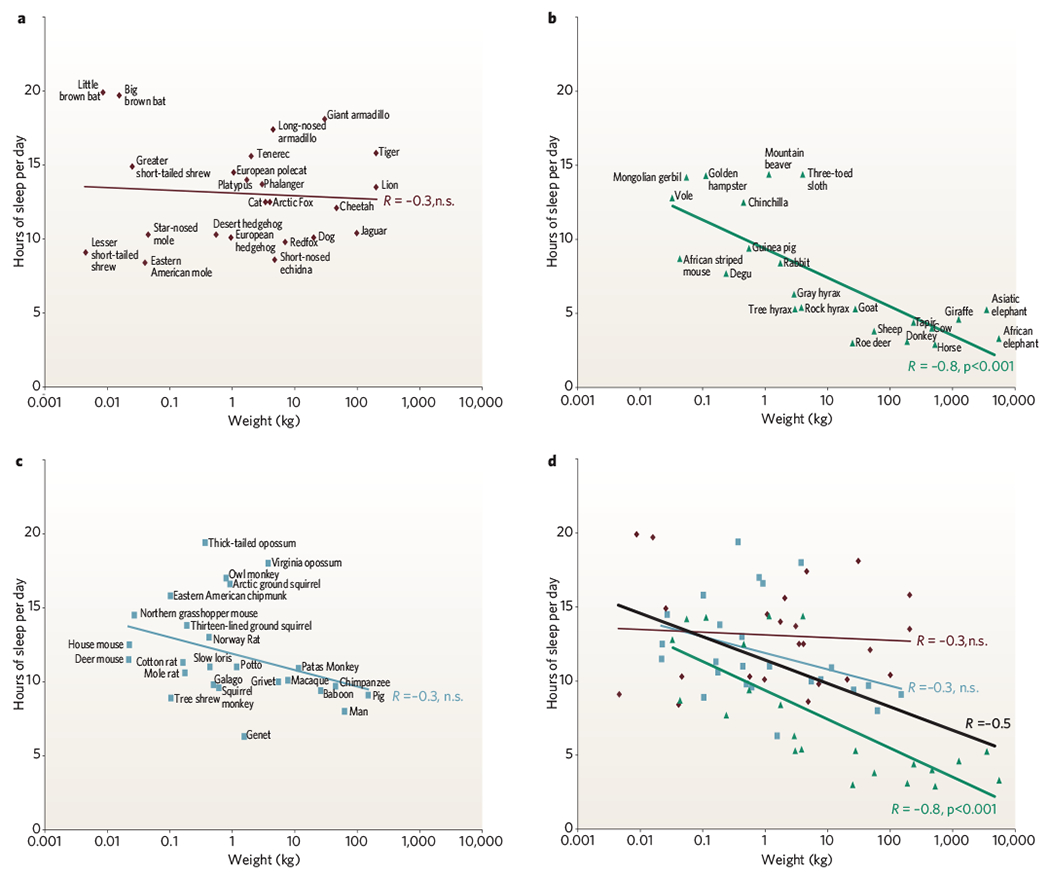

Figure 2 |. Sleep time in mammals.

a, Carnivores are shown in dark red; b, herbivores are in green and c, omnivores in grey. Sleep times in carnivores, omnivores and herbivores differ significantly (P < 0.0002, F test, d.f. 2,68), with carnivore sleep amounts significantly greater than those of herbivores (P < 0.001, t-test, d.f. 24, 22). Sleep amount is an inverse function of body mass over all terrestrial mammals (black line). This function accounts for approximately 25% of the interspecies variance (d) in reported sleep amounts (regression of log weight against sleep amount, R = −0.5, P < 0.0001, n = 71). Herbivores are responsible for this relation because body mass and sleep time were significantly and inversely correlated in herbivores (R = −0.77, P < 0.001, d.f. 24), but were not in carnivores (R = −0.28, d.f. 24) or omnivores (R = −0.25, d.f. 25).

It is not easy to quantify sleep parameters throughout the animal kingdom and as a result all desired parameters are rarely measured. For example, arousal thresholds are rarely systematically measured as part of a phylogenetic sleep study. Evidence for homeostatic regulation of sleep (sleep rebound) is seldom sought. Most species have not been implanted with electrodes for monitoring muscle tone and other variables. Instead, estimates are often based on visual observations, with the observer forced to intuit the differences between quiet waking and sleep. Other factors such as temperature, light cycle, food and noise conditions, which all affect sleep, have often not been controlled for. The age and health of the animals observed can vary, particularly depending on whether observations are made on animals in the wild or in the zoo. Often, observations of only one or two individuals are the source of the reported sleep amount of a given species. In animals observed in the wild, the weight of the subject is often not known, and in many cases the typical adult body weight, brain weight and other anatomical and physiological parameters cannot be or have not been precisely determined. Despite these sources of noise, significant relationships between weight, sleep time and diet are apparent. Source data for this figure were mainly from ref. 25.