Abstract

Endocytosis mechanisms are one of the methods that cells use to interact with their environments. Endocytosis mechanisms vary from the clathrin-mediated endocytosis to the receptor independent macropinocytosis. Macropinocytosis is a niche of endocytosis that is quickly becoming more relevant in various fields of research since its discovery in the 1930s. Macropinocytosis has several distinguishing factors from other receptor-mediated forms of endocytosis, including: types of extracellular material for uptake, signaling cascade, and niche uses between cell types. Nanoparticles (NPs) are an important tool for various applications, including drug delivery and disease treatment. However, surface engineering of NPs could be tailored to target them inside the cells exploiting different endocytosis pathways, such as endocytosis versus macropinocytosis. Such surface engineering of NPs mainly, size, charge, shape and the core material will allow identification of new adapter molecules regulating different endocytosis process and provide further insight into how cells tweak these pathways to meet their physiological need. In this review, we focus on the description of macropinocytosis, a lesser studied endocytosis mechanism than the conventional receptor mediated endocytosis. Additionally, we will discuss nanoparticle endocytosis (including macropinocytosis), and how the physio-chemical properties of the NP (size, charge, and surface coating) affect their intracellular uptake and exploiting them as tools to identify new adapter molecules regulating these processes.

Keywords: Endocytosis, Clathrin-Mediated Endocytosis, Caveolin-Mediated Endocytosis, Macropinocytosis, Nanoparticle

1. Introduction

In the study of many malignant diseases and their progression, including various cancers, numerous signaling and molecular protein targets have been identified as critical for cellular uptake pathways. However, which proteins and molecular players determine the endocytosis mechanism responsible for uptake of specific extracellular materials remain largely unknown. Endocytosis plays a major role in the interaction between cells and their environment, with most research focused on receptor-mediated endocytosis (RME), specifically phagocytosis, clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME), and caveolin- mediated endocytosis (CavME) (Figure 1). All variants of RME, colloquially termed “cell-eating”, are initiated by extracellular cargo binding to specific receptors on the plasma membrane. Cargo binding leads to membrane invagination and initiation of signaling cascades which promote cargo engulfment and downstream processing in turn promoting cell survival and proliferation (Marsh 1999, Kirchhausen 2000, Schmid and McMahon 2007, Doherty and McMahon 2009, Rosales and Uribe-Querol 2017). While RME processes are all similar, they also have distinct characteristics, including: the nature of the cargo, cellular factors involved, activation signals, and fate of the internalized cargo (Mercer and Helenius 2009). RME is a critical cellular function, however, cells can also utilize the less specific micropinocytosis as an uptake mechanism. While the mechanistic aspects of RME and macropinocytosis have been extensively studied for decades, more in-depth studies of disease- associated or oncogenic-driven endocytosis are warranted (Mosesson, Mills et al. 2008, Xiong, Rao et al. 2020). For example, Xiong et.al, reported on a molecule, ubiquitin binding domain protein-2 (UBAP2), which drives macropinocytosis and also regulates mutated activated KRAS (GTP-bound RAS) in pancreatic cancer cells, illustrating one facet of how cellular uptake molecules can drive disease progression (Xiong, Rao et al. 2020).

Figure 1: An overview of cellular endocytosis mechanisms.

Research has predominantly focused on variations of Receptor-Mediated Endocytosis, including phagocytosis (left two columns). Pinocytosis and Macropinocytosis have been studied to determine their niche in the endocytosis fields and are independent of specific cargo in contrast to RME (right two columns). All endocytosis mechanisms eventually lead to Rab5 positive early endosome formation and mature into Rab7 positive late multi-vesicular endosomes.

Nanoparticles (NPs) have become important materials in various medical applications including drug or gene delivery, imaging, diagnosis, and treatment of disease. In addition, NPs can be specifically designed or engineered for application to the identification of novel molecular targets associated with disease onset or progression (Figure 2) (Hossen, Elechalawar et al. 2021). In a biological system, NPs interact with the phospholipid bilayer cellular membrane and internalized by endocytosis (i.e. RME or macropinocytosis). Distinct proteins drive NP intracellular transport through particular endocytosis mechanisms; these mechanisms can be different depending on cellular status (e.g. healthy vs disease- associated cells) (Commisso, Davidson et al. 2013). Within 30 seconds of NP administration, proteins from the blood will be adsorbed onto the NP surface, resulting in a NP-protein complex called the NP- Protein corona (NP-PC), the NP-PC can affect the endocytosis uptake pathway of the NP (Elechalawar, Hossen et al. 2020). In general, many FDA-approved drugs, including doxorubicin and gemcitabine, are taken up by cells via passive diffusion and this uptake pattern may not be beneficial to identify or discover new malignant endocytosis machinery proteins associated with disease progression. In this review, we focus on macropinocytosis, a lesser studied endocytosis mechanism than the RME mechanisms. Additionally, we also review NP endocytosis (including macropinocytosis), and how the physicochemical properties of the NP (size, charge, and surface coating) affect endocytosis. Teasing apart how NPs interact with the various endocytosis pathways (including macropinocytosis) may lead to their use in the discovery of larger proteins relevant to disease progression with significant advantages over using simple therapeutic molecules.

Figure 2:

Schematic illustration of work-flow for the preparation, characterization, analysis and identification of new molecular target proteins in the protein corona around gold nanoparticles using cell lysates (RIPA or urea lysis) and low-abundance proteins enriched by immunocentrifugation of serum/plasma. Reprinted from “Experimental conditions influence the formation and composition of the corona around gold nanoparticles.” by Hossen, Elechalawar et al., Cancer Nanotechnology. This figure is included in the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License: To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

2. A Brief History of Macropinocytosis

Macropinocytosis was first described by Warren Lewis in the 1930s as a nutrient uptake mechanism in mammalian macrophages (Lewis 1931, Lewis 1937, Bloomfield and Kay 2016). In both mouse macrophages and sarcoma cells, Lewis used time-lapse microcinematography to observe the ruffling and fluid engulfment that are considered the keystones of macropinocytosis research (Swanson and King 2019). As Lewis proposed, macropinocytosis is likely an innate function of macrophages, since they are essential for removal of cellular debris produced by injuries, infections or other damage. When not participating in the innate immune response, it is probable that macrophages are actively engaging in macropinocytosis, allowing the cell to take in tissue fluids, digest the contents, and diffuse the remaining fluid back into the extracellular space (Lewis 1931, Lewis 1937). To establish that macropinocytosis is a function of macrophages, Lewis, citing Vera Koehring, demonstrated in a series of experiments utilizing a neutral red dye (an indicator of digestive enzyme activity) that fluids, and their contents, taken up by macrophages via macropinocytosis are digested by the cells (Koehring 1930, Lewis 1937). In the same era as Lewis, others showed that micropinocytosis is a feeding mechanism in several branches of Amoebozoa (e.g. Amoeba proteus and Dictyostelium discoideum) (Schaeffer 1916, Edwards 1925, Mast and Doyle 1933, King and Kay 2019). Eventually, various strains of Dictyostelium discoideum were able to be isolated and cultured in liquid medium due to their high rates of macropinocytosis; these laboratory strains have been the focus in many subsequent studies on macropinocytosis (Sussman and Sussman 1967, Watts and Ashworth 1970). In time, macropinocytosis would be used to distinguish large, fluid-filled vesicles from other, smaller-scaled pinocytosis mechanisms (Palm 2019). Today, macropinocytosis has been found in numerous cell types and is recognized as an evolutionarily conserved form of endocytosis. Most of what is known about macropinocytosis comes from studies focused on amoebae, intracellular pathogens, immune cells, and various cancers (Sallusto 1995, Bondy-Denomy, Pawluk et al. 2013, Liu and Roche 2015, Canton 2018, Lee, Mohamed Hussain et al. 2019, Lee, Pasquarella et al. 2019). Intracellular pathogens, such as viruses, utilize the cell’s uptake of extracellular fluid to access the cytoplasm, where they hijack the host-cell cellular machineries (e.g. Herpes simplex virus and Human Immunodeficiency Virus) (Mercer and Helenius 2009, Mercer, Schelhaas et al. 2010, Lee, Mohamed Hussain et al. 2019, Lee, Pasquarella et al. 2019). Dendritic cells and macrophages are able to undergo constitutive macropinocytosis, allowing the cells to better sample the environment for potential antigens for antigen presentation and cell migration (Sallusto 1995, Swanson and Watts 1995, Aderem and Underhill 1999, West 2004, Swanson 2008, Bohdanowicz, Schlam et al. 2013, Liu and Roche 2015, Yoshida, Pacitto et al. 2018, Charpentier, Chen et al. 2020, de Winde, Munday et al. 2020) (Figure 3). In cancers, macropinocytosis is associated with broad aspects of tumorigenesis, including cell proliferation, growth, survival, and metastasis (Mack, Whalley et al. 2011, Ha, Bidlingmaier et al. 2016). Cancer cells exploit macropinocytosis as an efficient method to internalize various components on the plasma membrane and downregulate apoptosis events.(Chen, Bozza et al. 2014, Ha, Bidlingmaier et al. 2016). Prostate and breast cancer cells can translocate growth factor receptors from the membrane to the cytoplasm, allowing the cell to be re-sensitized to the growth factor stimulation (Koumakpayi, Le Page et al. 2011, Schmees, Villaseñor et al. 2012, Reif, Adawy et al. 2016). Macropinocytosis is often used by cancer cells to replenish scarce nutrients for sustained propagation within the tumor microenvironment (TME). Ras-transformed pancreatic cancer cells can upregulate macropinocytosis to internalize and degrade albumin as a source of glutamine, one of the most limited nutrients in the TME (Commisso, Davidson et al. 2013, Kamphorst, Nofal et al. 2015). After nearly a century, macropinocytosis, now colloquially termed “cell-drinking”, has become a widely recognized endocytosis mechanism alongside the RME mechanisms.

Figure 3: Regulation and Utility of Macropinocytosis.

The Regulation of Macropinocytosis (Left General Side): Macropinocytosis is typically initiated through some stimulation factor, either growth factor stimulation, or cell starvation, leading to the activation of Ras proteins. Ras activity can be modulated by proteins (e.g. UBAP2) or oncogenically activated (KRAS G12V) to initiate a signaling cascade of CDC42, Rac1 and Pak1 activation. This signaling cascade leads to actin polymerization and membrane ruffling. Simultaneously, PI3K depletes PI(3,4)P2 while PI(3,4,5)P3 is generated in the membrane ruffles promoting macropinosome formation and closure. Utility of Macropinocytosis in Various Cell Types (Right General Side): Macropinocytosis can be blocked through pH modifications of the cell (e.g. EIPA) preventing macropinosome closure. Oncogenically activated KRAS can promote V-ATPase translocation to the plasma membrane. Viruses can exploit and/or stimulate macropinocytosis of cells to promote cell uptake and, in some cases, genomic integration via bypassing typical cellular sensors. Alternatively, macropinocytosis is a predominant environmental sampling mechanism of macrophages and immature dendritic cells, leading to antigen presentation. Nanoparticle-covered proteins can utilize macropinocytosis uptake into cells to discover macropinocytosis or disease-related protein identification.

3. What is Macropinocytosis?

Macropinocytosis is defined as the nonspecific uptake of extracellular fluid, and its contents, into large vacuoles into the cell (Lewis 1931, Mercer and Helenius 2009, Bloomfield and Kay 2016), and has an intensely studied signaling pathway that results in macropinosome formation. Ultimately the fate of the macropinosome can vary based on the protein contents of the fluid, as well as the proteins in the membrane of the macropinosome itself (Figure 3). Macropinocytosis is intricately linked with actin polymerization, and, consequently, is disrupted by actin polymerization inhibitors, such as cytochalasin D (Gold, Monaghan et al. 2010, Recouvreux and Commisso 2017). Actin strands polymerize against the plasma membrane to form protrusions, called membrane ruffles (Welliver, Chang et al. 2011, Hoon, Wong et al. 2012, Bernitt, Koh et al. 2015, Valdivia, Goicoechea et al. 2017). When membrane ruffling is profound, ruffles will occasionally fold inwards towards the basal membrane, fuse, and form the large vesicle structure or macropinosome (Johannes and Lamaze 2002, de Carvalho, Barrias et al. 2015, Buckley and King 2017). Two types of ruffle have been reported that lead to macropinosome formation: planar ruffles and circular dorsal ruffles (Hoon, Wong et al. 2012, Bernitt, Koh et al. 2015, Valdivia, Goicoechea et al. 2017). Generally, both ruffle types fold back on themselves into the basal membrane, but, in rarer cases, de novo actin rings can form on the plasma membrane (Swanson 2008, Bohdanowicz, Schlam et al. 2013, Swanson and King 2019) (Figure 3). While both types of ruffle have described molecular players, the regulation from ruffle to macropinosome is not fully described. Macropinosomes are most often distinguished from other RME-mediated endosomes based on their large diameters ranging from 0.2μm-10μm (Welliver, Chang et al. 2011, Buckley and King 2017). Experimentally, macropinosomes can be labeled using high molecular weight dextran molecules, which are too large to enter the cell through other endocytosis mechanisms (Wang, Kerr et al. 2010, Commisso, Flinn et al. 2014, Wang, Teasdale et al. 2014) (Figure 3). The currently available inhibitors of macropinocytosis include the previously mentioned actin polymerization inhibitors (e.g. cytochalasin D) (Gold, Monaghan et al. 2010, Recouvreux and Commisso 2017), PI3K blockers (e.g. wortmannin) (Ivanov 2008) and sodium/hydrogen exchange inhibitors (ethyl-isopropyl amiloride [EIPA])(Ivanov 2008, Koivusalo, Welch et al. 2010).

4. Macropinocytosis Regulation

Key regulators of actin polymerization, such as members of the Ras gene superfamily (e.g. Ras and Rac) are associated with macropinocytosis activity (Fujii, Kawai et al. 2013, Hodakoski, Hopkins et al. 2019, Williams, Paschke et al. 2019, Buckley, Pots et al. 2020, Hobbs and Der 2020). Proteins in the Ras superfamily encode for small guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases) that serve as molecular ON- OFF switches for various signaling pathways. Additional molecules known to play a role in macropinocytosis regulation include Cdc42, Arf6, and Rab5, among others (Garrett, Chen et al. 2000, Nobes and Marsh 2000, Feliciano, Yoshida et al. 2011, Humphreys, Davidson et al. 2013, Schulz, Stutte et al. 2015, Tang, Tam et al. 2015, Williamson and Donaldson 2019, Maxson, Sarantis et al. 2020) (Figure 3). During early macropinosome formation and maturation, evidence suggests that expression of Ras and phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3) predominate in those regions of the ruffles in the plasma membrane. These molecules are critical to the early development of macropinosomes, as their ablation (either genetically or chemically) results in the inhibition of macropinosome formation (Araki, Egami et al. 2007, Hoeller, Bolourani et al. 2013, Williams, Paschke et al. 2019). Activation of Ras proteins leads to a cascade of downstream effector signaling pathways, including, but not limited to, Rac, Cdc42, PI3K and Raf activation with a range of consequences in the cell. Downstream of Ras activation, Rac and Cdc42 are activated to stimulate actin polymerization through p21-activated kinase 1 (Pak1) or ARP2/3, resulting in an increase in ruffling along the plasma membrane (Dharmawardhane, Sanders et al. 1997, Dharmawardhane, Schurmann et al. 2000, Donaldson 2019). In mammalian cells, PIP3 is lost from the macropinosomes shortly after closure, resulting in the generation of phosphatidylinositol (3,4)-bisphosphate [PI(3,4)P2] which is utilized as the macropinosome progresses through the endocytic pathway (Araki, Egami et al. 2007, Hoeller, Bolourani et al. 2013, Egami, Taguchi et al. 2014). Similarly, members of the Rab family of small GTPases (e.g. Rab5 and Rab7) play a role in macropinosome formation and maturation. Rab5 is associated with areas in the plasma membrane where ruffles predominate and stays associated with the macropinosome through its maturation into a more conventional early endosome (Morishita, Wada et al. 2019). Rab7 expression predominates in the macropinosome once it has been processed into the late multi-vesicular endosomes (Morishita, Wada et al. 2019). While Ras, Rac, and Cdc42 signaling are critical for the early steps of macropinocytosis (i.e., membrane ruffling and formation of macropinocytic cups), PI3K activity seems to be specifically required for macropinosome closure (Amyere, Payrastre et al. 2000, Araki, Egami et al. 2007). As macropinosomes close, PI(3,4)P2 is depleted while PI(3,4,5)P3 is generated by PI3K, allowing for a coordinated actin remodeling to allow for membrane fusion and macropinosome closure. Closure and fission of the macropinocytic cup results in the formation of a large, aqueous-filled vesicle that must be processed by the cell (Egami, Taguchi et al. 2014, Swanson and King 2019). Unlike other endocytosis mechanisms, macropinocytosis is not dependent on a specific cargo to stimulate its activity. However, macropinocytosis seems to be acutely related to growth factor stimulation, as many of the molecules that regulate macropinosome formation and maturation are themselves sensitive to growth factor stimulation (Schmees, Villaseñor et al. 2012, Salloum, Jakubik et al. 2019, Weerasekara, Patra et al. 2019). Macropinocytosis induction has been reported by several growth factors, including epidermal growth factor (EGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (West, Bretscher et al. 1989, Racoosin and Swanson 1992, Bryant, Kerr et al. 2007, Schmees, Villaseñor et al. 2012, Lou, Low-Nam et al. 2014, Nakase, Kobayashi et al. 2015, Hagiwara and Nakase 2018, Redka, Gütschow et al. 2018, Yoshida, Pacitto et al. 2018). In many of these cases, the growth factor stimulates membrane ruffling through the activation of Ras, Rac, and Cdc42.

5. Macropinocytosis in cell biology:

5.1. Viruses:

A variety of extracellular organisms and particles, including bacteria and viruses, can induce ruffling of the cell, independent of growth factor stimulation, to promote their internalization by the cell (Francis, Ryan et al. 1993, Zenni, Giardina et al. 2000, Mercer, Schelhaas et al. 2010, García-Pérez, De la Cruz-López et al. 2012). In the late 2000s, Mercer et. al reported that one form of infectious Vaccinia virus (intracellular mature virus [MV]) was able to induce blebbing in the cellular membrane, many of which contained regulators of macropinocytosis, including Rac1, Ezrin, and Pak1 (Mercer and Helenius 2008). When MVs incubated with cells, Pak1 activation occurred, signaling an activation in the macropinocytosis pathways, and MVs could be inhibited with macropinocytosis inhibitors, such as EIPA (Mercer and Helenius 2008). Various viruses are able to exploit macropinocytosis to enter the cell. Mature virus particles are able to either mimic cellular components or bind directly to the plasma membrane to promote membrane ruffling events and macropinocytosis (Meier, Boucke et al. 2002, Mercer and Helenius 2008, Mercer and Helenius 2009, Kalin, Amstutz et al. 2010, Mercer, Knébel et al. 2010, Rizopoulos, Balistreri et al. 2015). In 2010, Kälin et.al showed that human adenovirus serotype 35 (Ad35) utilized macropinocytosis as an infectious entry pathway into human epithelial and kidney cells. Ad35 requires CD46 and integrins for infection, but incorporation of Ad35 into the cell was macropinocytosis-dependent while being RME independent (Kälin, Amstutz et al. 2010). Kälin later compared Ad35 is to other adenoviruses (namely Ad2/5), and showed differences in their cell entry methods. Internalization of HIV-1 is also facilitated by micropinocytosis (Liu, Lossinsky et al. 2002, Yasen, Herrera et al. 2018). In 2018, Yasen et. al. investigated HIV-1 internalization by various epithelial cells, and showed that HIV-1 utilizes multiple methods of endocytosis, both RME and macropinocytosis, to facilitate viral penetration; viral internalization was inhibited by endocytosis inhibitors (~50% and ~60% for RME and macropinocytosis respectively) (Yasen, Herrera et al. 2018).

5.2. Immune-relevant cells

Among the immune relevant cell types, dendritic cells and macrophages have been most studied in the context of macropinocytosis. Given their function in the immune response as antigen presenting cells (APCs), it makes sense that these cells have the ability to undergo constitutive macropinocytosis. Along with oncogenic cells, dendritic cells and macrophages are part of a select group of known cells with this capability, at the time of writing. Constitutive macropinocytosis allows for greater uptake of extracellular fluid, in a nonspecific manner, allowing the cell to process potential antigenic peptides and translocate to the thymus to educate lymphocytes (Sallusto 1995, West 2004, Swanson 2008, Yoshida, Pacitto et al. 2018, Swanson and King 2019). This characteristic seems to be, for the most part, limited to these APCs. B cells and, to a lesser extent, macrophages typically utilize phagocytosis and antigen-specific B cell receptors (B cells only) as their main antigen processing mechanism (Lanzavecchia 1990, Aderem and Underhill 1999). Currently, the ability of B cells to undergo macropinocytosis is largely unknown. In one of the few studies of macropinocytosis in B cells, Garcia-Perez et. al. showed that while uninfected B cells have a low capacity for macropinocytosis, infection with live bacteria (e.g. S. typhimurium) stimulated macropinocytosis. Similarly, the relevance macropinocytosis to T cells remains largely unknown. In 2020, Charpentier et. al. demonstrated that primary mouse and human T cells engage in constitutive macropinocytosis that is enhanced in response to CD3/CD28 antibody stimulation and is essential for the growth of these antibody stimulated T cells in harsh conditions (Charpentier, Chen et al. 2020) (Figure 4); they used a combination of flow cytometry, scanning electron microscopy, and dextran uptake to illustrate T-cell macropinocytosis (Figure 4). Furthermore, T-cell mTORC1 signaling activation and sustainment was dependent on macropinocytosis based on the role of micropinocytosis in bringing essential amino acids into the cell, providing a link between macropinocytosis and T-cell growth (Charpentier, Chen et al. 2020).

Figure 4: The discovery of macropinocytosis in T-cells.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) images of murine CD4+ T cells, unstimulated or stimulated with CD3/28 mAb for 16 h. Macropinocytic cups at different stages of development are indicated (arrows) Reprinted from “Macropinocytosis drives T cell growth by sustaining the activation of mTORC1” by Charpentier, Chen et al., 2020. Nature Communications. Volume 11. This figure is included in the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License: To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. (Figure 2, Panel B).

5.3. Cancer Contexts

Cancer cells typically exploit any advantage they can acquire in order to promote cell growth and proliferation. In pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), as well as other cancer types, the contributions of oncogenic mutations in small GTPases, such as KRAS, to disease pathogenesis and prognosis are well known (Almoguera, Shibata et al. 1988, Wolfgang, Herman et al. 2013, Siegel, Ma et al. 2014, Commisso and Debnath 2018, Aier, Semwal et al. 2019). Recently, macropinocytosis was shown to correlate with the proliferation/survival of Ras-transformed (typically KRAS) tumor cells under harsh environmental conditions; extracellular amino acid availability is restricted in more developed tumor masses (Palm, Park et al. 2015, Nofal, Zhang et al. 2017, Michalopoulou, Auciello et al. 2020). Due to their high nutrient requirements, KRAS-driven cancerous cells utilize numerous nutrient acquisition pathways, notably micropinocytosis (White 2013, Cao, Wang et al. 2019, Pupo, Avanzato et al. 2019). Changes in cell metabolism in Ras-driven cancers is a burgeoning research field; it is clear that the altered behavior of tumor cells bestows critical advantages for cell proliferation and survival (Commisso, Davidson et al. 2013). Since, to date, no therapy directly targeting Ras proteins has been successful, the link between Ras and macropinocytosis raises the possibility that macropinocytosis could be a viable therapeutic target for Ras-driven cancers. The Ras genes (KRAS, HRAS, and NRAS) are among the most frequently mutated genes in all cancers (~27%), with most of the mutations resulting in gene activation (Tate, Bamford et al. 2018, Waters and Der 2018). In a 2019 article Zhang and Commisso state that “Oncogenic Ras mutations are very common in a variety of tumor types, including most cases of PDAC, 25–30% of non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLCs), approximately 13% of bladder cancers, and about 40% of colorectal cancers” (Zhang and Commisso 2019). While Ras mutations are less common in bladder cancer than in PDAC, oncogenic HRAS mutations lead to an increase in macropinocytosis activity (Commisso 2019). In cases of superficial bladder carcinoma, Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) is used as an effective treatment; in bladder carcinoma cases with KRAS and HRAS mutations (G12V), the cancer cells internalized more BCG than control cells through activation of Pak1 (Redelman-Sidi, Iyer et al. 2013). In lung cancer, some tumors are dependent on oncogenic Ras expression, with KRAS being the predominant oncogene. Studies with KRAS and macropinocytosis in NSCLCs showed recycling of cell surface receptor integrin αvβ3, and its modulator galectin-3, to control tumor growth and metastasis (Singh, Greninger et al. 2009, Commisso 2019). Certain cases of NSCLC have been shown to utilize macropinocytosis to gain higher levels of ATP to support their greater energy requirements in the harsh TME (Pellegatti, Raffaghello et al. 2008, Qian, Wang et al. 2014). Consequently, KRAS is considered to be a predominant oncogene in PDAC and numerous other cancer types. KRAS functions in either a bound guanosine-triphosphate (GTP) active state (ON) or a bound guanosine-diphosphate (GDP) state (OFF). In normal cells, KRAS is predominately found in its GDP-bound form, but is stimulated by particular cell surface receptors, quickly switching to its GTP-bound form to engage with its effector proteins. Activated KRAS mutations in cancers typically encode for single amino acid mutations that are “primarily (98%) at one of three mutational hotspots: glycine-12 (G12), glycine-13 (G13), or glutamine-61 (Q61)” (Waters and Der 2018). These activation mutations allow for KRAS to be persistently active, resulting in constitutive activation of various cell growth/proliferation pathways, including micropinocytosis (Waters and Der 2018). To date, there is no clinical therapeutic that directly targets any of the Ras family of proteins (Tate, Bamford et al. 2018, Waters and Der 2018), although efforts now center on indirect strategies to target Ras signaling. NSCLC human A549 cells (KRAS G12S) and PANC1 PDAC cells (KRAS G12D) exhibited high levels of micropinocytosis (Finicle, Jayashankar et al. 2018). While it is not known whether the same mutation of KRAS results in different effects on macropinocytosis, KRAS-driven macropinocytosis has been demonstrated to be relevant in both in vitro and in vivo (Finicle, Jayashankar et al. 2018). Similarly, our group has demonstrated high levels of macropinocytosis in various PDAC cell lines (highlighted by AsPC1, PANC1, and BxPC3 cells) with both wild-type KRAS and oncogenic KRAS mutations (Xiong, Rao et al. 2020).

6. Importance of nanoparticle endocytosis

Depending on their surface and physicochemical properties NPs interact differently with biological systems. These interactions are also dependent on the nature of the biological systems, e.g extracellular fluids vs. body fluids, cells cultured in vitro vs interaction with tissues in vivo. The nature of these interactions dictates intracellular uptake or endocytosis of the NPs. Importantly, cellular uptake mechanisms of NPs are dependent on their surface physicochemical properties (size, charge, shape and their surface coating) (Lammel, Mackevica et al. 2019). For example, Zhao et. al. reported on silica nanocapsules (SNC) of 150 nm and with Young’s modulus ranging from 560 kPa to 1.18 GPa, and studied their interactions with the cellular membrane of macrophages or cancer cells to demonstrate effects of mechanical properties on rates of endocytosis. They found that the stiff SNCs remained in an intact, spherical shape and exhibited a good rate of uptake into the cells. In contrast, soft SNCs were deformed after their interactions with the cellular membrane, decreasing their uptake by the cell (Lammel, Mackevica et al. 2019). These studies illustrate the importance of NP design or engineering for their interactions with cell membranes that dictate endocytosis.

7. Factors influencing nanoparticle endocytosis pathways

NPs can be tailored to alter intracellular signaling events. (Figure 5). For example, Hossen et. al., reported that incorporation of gold NPs in traditional liposomal formulations of siRNA enhanced the gene silencing efficacy of the resulting hybrid nanosystem. This enhanced gene silencing efficacy of auroliposomal-siRNA formulation was attributed to switching of the endocytosis pathways from a combination of clathrin and caveolar uptake pathways to mostly caveolar uptake. They further demonstrated that switching of this uptake pathway resulted in reduced fusion of caveosome with lysosome, thereby preventing degradation of the encapsulated siRNA (Hossen, Wang et al. 2020). Thus, engineering of NPs can be critical, not only for their intracellular fate but in regulating intracellular events.

Figure 5: Overview of how nanoparticles can be utilized to identify novel molecular protein targets in various endocytosis pathways.

The cellular uptake process of nanoparticles is regulated by several known and unknown endocytosis machinery proteins. Each type of nanoparticle has a particular endocytosis process for their cellular entry. Nanoparticle clusters (> 200nm size) are generally taken up by cells by micropinocytosis, and the surface coating of nanoparticles decides their clathrin- or caveolae-mediated endocytosis process pattern. Several known and unknown molecular players are involved in regulating these processes. Discovery of these unknown malignant proteins (denoted in red) will lead to development of new drugs or inhibitors. [CME-clathrin mediated endocytosis, CME- Caveolae mediated endocytosis]

7.1. Size and shape

The size and shape of NPs have tremendous influence on endocytosis pathway which results in changes in their uptake efficiency (Chithrani, Ghazani et al. 2006). For example, spherical gold NPs have higher cellular uptake profile than rod-shapes gold Nps of similar size (Foroozandeh and Aziz 2018). This possibly results from interactions with cellular membranes and different endocytosis patterns. NPs with sizes of 100–200 nm enter cells via clathrin- or caveolae-mediated pathways and those of 250 nm to 3–5 μm via phagocytosis or macropinocytosis. For example, bare gold NPs are taken up by cells using macropinocytosis due to their partial aggregation resulting in large particles. In contrast, the corresponding PEGylated gold NPs were taken up by cells using clathrin- or caveolae- mediated endocytosis due to their smaller size (Brandenberger, Muhlfeld et al. 2010). Based on size, NPs are taken up by the cells via different endocytosis mechanisms, and this determines the ultimate functionalization of the NPs (Sabourian, Yazdani et al. 2020). Among gold NPs of different sizes, 50nm particles showed more extensive cellular uptake patterns than other sizes (Chithrani, Ghazani et al. 2006). In another study, Lammel et. al., reported a study on endocytosis of TiO2 NPs and demonstrated intracellular trafficking and fate of TiO2 NPs in fish liver parenchymal cells (RTL-W1) (Lammel, Mackevica et al. 2019). Only the 30–100nm agglomerates underwent caveolae mediated endocytosis and were internalized whereas the larger size agglomerates remained in the medium (Lammel, Mackevica et al. 2019). Thus, NP size is a primary determinant of the endocytosis pathway triggered by endocytosis machinery proteins, and further determines their cellular uptake efficiency (Frohlich 2012, Lammel, Mackevica et al. 2019). The size of NPs is less of a factor in macropinocytosis due to its non-specific nature. The uptake of extracellular fluid into the cell allows for NPs of sizes from a few to several hundred nanometers to come into the cell with little extra effort by the cell (Foroozandeh and Aziz 2018).

7.2. Surface Charge

In addition to NP size, NP surface charge has a large influence on endocytosis. Generally, the negative charge on the phospholipid head group (which predominately makes up the cellular membrane) has a greater affinity for positive charged NPs than either negatively charged or neutral NPs. However, negatively charged NPs have a higher uptake rate than do neutral NPs, indicating a role for charge overall in uptake (Goodman, McCusker et al. 2004, Lovric, Bazzi et al. 2005). Jiang and co-workers demonstrated that pristine polystyrene NPs (PS-NPs) internalize via clathrin-mediated endocytosis, but after amine functionalized modification resulted in positively charged NPs they show clathrin- independent endocytosis with increased uptake profile compared to unmodified PS-NPs (Jiang, Dausend et al. 2010). Together, these results demonstrate the role of charge in NP endocytosis patterns (Frohlich 2012), possibly due to the involvement of the various endocytosis machinery. In the case of charged NPs, the mode of endocytosis largely depends on their surface functionalization (Zaki, Nasti et al. 2011). In general, NPs which undergo caveolae-mediated endocytosis tend to bypass lysosomal association yielding greater cellular internalization; this will be beneficial in nanomedicine for improved NP engineering (Conner and Schmid 2003, Hossen, Wang et al. 2020). Using the micropinocytosis inhibitor EIPA, Dausend et. al. demonstrated positively charged NPs are mainly internalized by macropinocytosis whereas clathrin-/caveolae-dependent endocytosis is the mechanism for the uptake of negatively charged NPs (Dausend, Musyanovych et al. 2008, Foroozandeh and Aziz 2018).

7.3. Electrostatic forces or Van der Waal’s forces

It is believed that aggregated (strongly bonded) NPs or agglomerated (weekly bonded) NPs behave differently compared to individual NPs because of stronger or weaker electrostatic forces between the particles. If electrostatic repulsive forces between the NPs are weaker than Van der Waal’s forces, it results in aggregation or agglomeration of NPs and, as a result, the NPs show a different cellular uptake pattern.

7.4. Application of NPs to identify endocytosis mechanisms

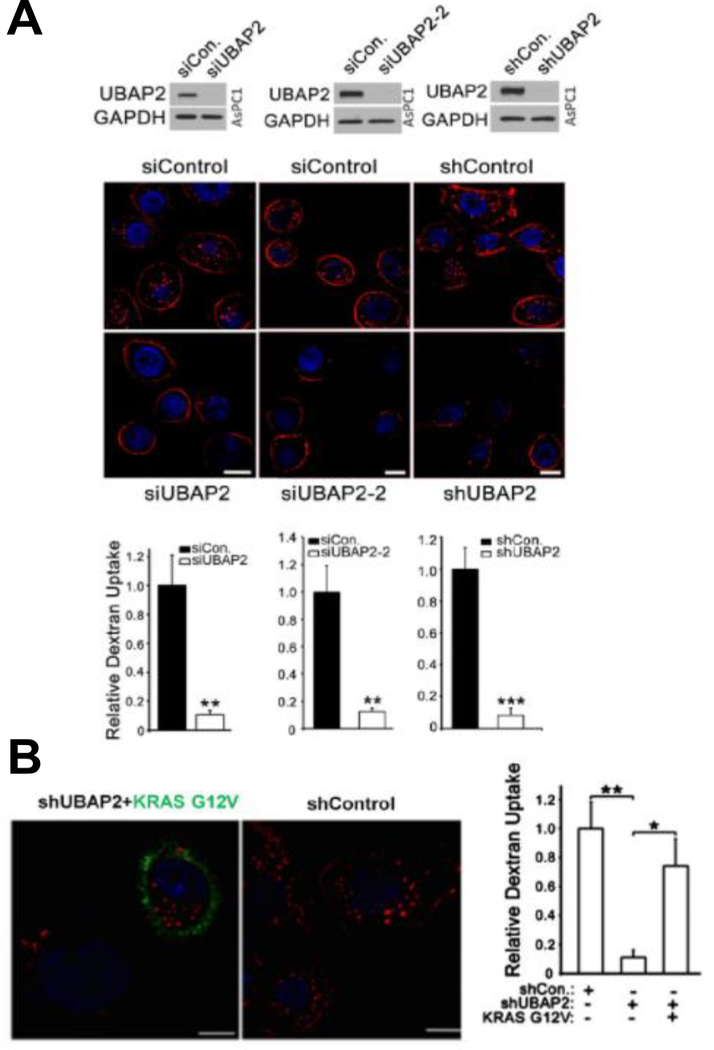

Bhattacharya et.al, reported the difference in cellular internalization patterns of 5nm gold NPs either partially or fully coated with the anti-EGFR antibody cetuximab (Au-C225-P and Au-C225-C, respectively). They showed that naked and fully covered NPs required clustering in glycosphingolipid (GSL) and exhibited dynamine-2 dependent caveolar-mediated endocytosis. However, partially coated NPs exhibited dynamin-independent but Cdc-42-dependent pinocytosis/phagocytosis along with actin polymerization (Bhattacharyya, Singh et al. 2012). Experimentally, Bhattacharya et. al. inhibited Au- C225-P and Au-C225-C uptake at different levels when treated with cytochalasin D and β- methylcyclodextrin to demonstrate the roles of macropinocytosis in lipid raft-dependent endocytosis respectively (Bhattacharyya, Singh et al. 2012). To visualize endocytosis of C225 and its various conjugates, they performed Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) on PANC-1 cells after treatment with the NPs. Figure 6A shows their confirmation of caveolar architectures in PANC-1 cells while Figure 6B shows the proximity of the NPs to the formation of a macropinosome via a large membrane ruffle event(Bhattacharyya, Singh et al. 2012). Utilizing NP characteristics, Xiong et. al, were able to identify UBAP2 as a relevant protein target in pancreatic cancer cells, demonstrating the potential application of NPs for target discovery when designed appropriately for a system (Xiong, Rao et al. 2020). Utilizing the techniques from Bhattacharya et.al, Xiong et. al. were able to utilize Au-C225-P to identify 243 uniquely associated proteins, including UBAP2. When examining UBAP2 further, they found that UBAP2 affected macropinocytosis but not other methods of endocytosis by examining changes in the uptake of transferrin (endocytosis) and dextran (macropinocytosis) under UBAP2 knockdown conditions in AsP1 cells (Xiong, Rao et al. 2020). Furthermore, Xiong demonstrated that UBAP2 promotes macropinocytosis by activating KRAS, a known player in many cancers, including PDAC (Figure 7A–B). By knocking down UBAP2 (both by silencing RNA and short-hairpin RNA techniques), macropinocytosis was reduced (Figure 7A) as shown through dextran uptake in AsPC1 cells; but introducing an activated KRAS vector (G12V) was able to rescue approximately 80% of the original phenotype (Figure 7B).

Figure 6: Comparison between nanoparticle uptake methods as seen through Transmission Electron Microscopy.

(A) TEM images of the arrest of the caveolar invagination of PANC-1 cells triggered by treatment with C225 or Au–C225-C (scale bar: 100 nm). (B) TEM image analysis shows the arrest of membrane invagination of fluid phase/micropinocytosis pathways as triggered by the treatment with Au-C225-P to PANC-1 cell at 4°C for 2h (Scale bar 500 nm). Adapted from “Switching the Targeting Pathways of a Therapeutic Antibody by Nanodesign” by Bhattacharyya, Singh, Pagano, et al. 2011, Angewandte Chemie International Edition. Volume 51, Issue 7. Copyright (2011) by John Wiley and Sons. Adapted with permission.

Figure 7: UBAP2 regulates macropinocytosis via KRAS activity in AsPC1 cells.

(A) UBAP2 silencing decreased TMR-Dextran uptake (red) in pancreatic cancer. Nuclei (blue) were stained by DAPI. Top: Silencing UBAP2 by siRNA or shRNA in pancreatic cancer cells (AsPC1). Two siRNAs are represented. Bottom: Corresponding quantifications of dextran uptake. Scale bar, 10μm. Mean ± SD; **P <.01; *P < .05. (B) Activated KRAS rescued the dextran uptake upon UBAP2 silencing (shUBAP2). KRAS G12V (green) and dextran (red) were visualized by IF. Scale bar, 10μm. (C) Quantification of dextran uptake. Mean ± SD; **P < .01; *P < .05. Adapted from “Ubiquitin-binding associated protein 2 regulates KRAS activation and macropinocytosis in pancreatic cancer” by Xiong, Rao, et al. 2020, The FASEB Journal. Volume 34, Issue 9. Copyright (2020) by John Wiley and Sons. Adapted with permission.

8. Future Directions and Discussion

Since its discovery, macropinocytosis research has predominately focused on the characterization of signaling mechanisms and the involved molecular players. This is critical to the continuing development of the macropinocytosis field as it branches into its unique niche of cell-environment interactions. Consequently, more studies are being performed on the applications of macropinocytosis. One such application is the exploitation of macropinocytosis-mediated NP uptake for molecular discovery of diagnostic and therapeutic targets. This review highlights the potential for more NP design considerations and how macropinocytosis functions from a cellular perspective in an effort to provoke new insights into NPs and macropinocytosis. Currently available LCMS/MS/MALDI-MS based spectrometric analysis methods can help to identify proteins from analysis of these samples but the low abundance of many malignant proteins may lead to incomplete results. To address this challenge, nanoproteomic-based LCMS/MS or MALDI analysis of NP-protein corona complex of the sample will yield more complete information for such malignant proteins. Subsequent assessment of their biological activity will elucidate novel endocytosis machinery proteins and their role in disease progression (Giri, Shameer et al. 2014). The field has advanced quickly; there are 113 publications retrievable from Pubmed using “macropinocytosis” as a key term and setting the year limits as 1975–2000. From 2000– 2020, there have been 1866 publications involving the term macropinocytosis as of the time of this review. In 2020, the relevance of UBAP2 to macropinocytosis and PDAC, were discovered utilizing NP technology, representing one of the first applications of NP design to identifying particular uptake methods, isolating proteins relevant to the uptake, and selecting one of these proteins for further study. Furthermore, there are many known and unknown endocytosis associated proteins identified through these two Au-C225 nanoparticle designs; there are many avenues to explore with this design, and the applications of adaptations to this design are brimming with potential.

Highlights.

Macropinocytosis relevance and signaling

Nanoparticle design and factors affecting nanoparticle delivery

Nanoparticle -driven discovery of novel proteins associated with macropinocytosis and endocytosis

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by 1R01CA253391-01A1, CA213278, 2CA136494, and P30 CA225500 Team Science grants. In addition, this work is also supported by the Peggy and Charles Stephenson Endowed Chair fund and TSET Scholar fund to PM. This work was also supported in part by the National Cancer Institute (R01CA205348), the Oklahoma Center for the Advancement of Science and Technology (HR16-085 and HF20-019), and the Peggy and Charles Stephenson Endowed Chair fund to WRC.

Biography

Nicolas Means

Nicolas Means is a graduate student in the lab of Dr. Priyabrata Mukherjee at the University of Oklahoma-Health Sciences Center. Nicolas’ work focuses on macropinocytosis and its role in cancer development.

Chandra Kumar Elechalawar, PhD

Dr. Chandra Kumar Elechalawar received his Ph.D from CSIR-Indian Institute of Chemical Technology (CSIR-IICT), India in 2018. Currently, he is working as postdoctoral fellow in Dr. Priyabrata Mukherjee lab at the Stephenson Cancer Center, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center (OUHSC), Oklahoma City, United States. His research topics are including developing EGFR-targeted gold nanoparticles for gemcitabine delivery to pancreatic cancer cells and immuno-liposomal gene/drug delivery systems for ovarian cancer and to discover new oncogenic targets using protein corona approach.

Wei R. Chen, PhD

Wei R. Chen is Professor and Stephenson Chair in the Stephenson School of Biomedical Engineering at the University of Oklahoma. Dr. Chen focuses on novel cancer therapies. His group developed localized ablative immunotherapy for metastatic cancers with promising outcomes in pre-clinical studies and preliminary clinical trials. He also focuses on immunologically modified nanoplatform for cancer treatment using nano-photo-immuno effects. He has published 170+ peer-reviewed articles and 180+ conference proceeding papers. He has been awarded 9 US patents and multiple international patents. He was elected as a SPIE (International Society of Optics and Photonics) Fellow in 2007.

Resham Bhattacharya, PhD

Resham Bhattacharya received her Ph.D., (2002) from the Bowling Green State University, Ohio. She is a tenured Associate Professor in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology and adjunct faculty in the Department of Cell Biology and a full-member of the Stephenson Cancer Center at the University of Oklahoma Health Science Center. Her research interests include investigating the basic and clinical translational aspects of molecular signaling in vascular pathologies and in gynecologic cancers, primarily ovarian and uterine cancer and have also reported several seminal observations on the nanomaterial-cellular interface pertaining to mechanisms of cellular uptake, drug delivery, nanodesign and novel signaling.

Priyabrata Mukherjee, PhD

Dr. Mukherjee’s research is centered at the interface between biology and materials science to address unmet challenges in human diseases. He is a tenured professor within the Department of Pathology at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center (OUHSC). He also serves as the Associate Director for Translational Research at the Stephenson Cancer Center and Co-Director for the Nanomedicine Program. He is an elected fellow of the Royal Society of Chemistry, UK (FRSC), American Institute of Medical and Biological Engineering (FAIMBE) and an elected Fellow of National Academy of Inventors (FNAI). Dr. Mukherjee is also a recipient of Presbyterian Health Foundation Presidential Professorship and Fred G. Silva Award at OUHSC.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest: All authors do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Aderem A and Underhill DM (1999). “MECHANISMS OF PHAGOCYTOSIS IN MACROPHAGES.” Annual Review of Immunology 17(1): 593–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aier I, Semwal R, Sharma A and Varadwaj PK (2019). “A systematic assessment of statistics, risk factors, and underlying features involved in pancreatic cancer.” Cancer Epidemiology 58: 104–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Almoguera C, Shibata D, Forrester K, Martin J, Arnheim N and Perucho M (1988). “Most human carcinomas of the exocrine pancreas contain mutant c-K-ras genes.” Cell 53(4): 549–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amyere M, Payrastre B, Krause U, Smissen PVD, Veithen A and Courtoy PJ (2000). “Constitutive Macropinocytosis in Oncogene-transformed Fibroblasts Depends on Sequential Permanent Activation of Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase and Phospholipase C.” Molecular Biology of the Cell 11(10): 3453–3467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Araki N, Egami Y, Watanabe Y and Hatae T (2007). “Phosphoinositide metabolism during membrane ruffling and macropinosome formation in EGF-stimulated A431 cells.” Experimental Cell Research 313(7): 1496–1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernitt E, Koh CG, Gov N and Dobereiner H-G (2015). “Dynamics of Actin Waves on Patterned Substrates: A Quantitative Analysis of Circular Dorsal Ruffles.” PLOS ONE 10(1): e0115857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhattacharyya S, Singh RD, Pagano R, Robertson JD, Bhattacharya R and Mukherjee P (2012). “Switching the targeting pathways of a therapeutic antibody by nanodesign.” Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 51(7): 1563–1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bloomfield G and Kay RR (2016). “Uses and abuses of macropinocytosis.” Journal of Cell Science 129(14): 2697–2705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bohdanowicz M, Schlam D, Hermansson M, Rizzuti D, Fairn GD, Ueyama T, Somerharju P, Du G and Grinstein S (2013). “Phosphatidic acid is required for the constitutive ruffling and macropinocytosis of phagocytes.” 24(11): 1700–1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bondy-Denomy J, Pawluk A, Maxwell KL and Davidson AR (2013). “Bacteriophage genes that inactivate the CRISPR/Cas bacterial immune system.” Nature 493(7432): 429–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brandenberger C, Muhlfeld C, Ali Z, Lenz AG, Schmid O, Parak WJ, Gehr P and Rothen-Rutishauser B (2010). “Quantitative evaluation of cellular uptake and trafficking of plain and polyethylene glycol-coated gold nanoparticles.” Small 6(15): 1669–1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bryant DM, Kerr MC, Hammond LA, Joseph SR, Mostov KE, Teasdale RD and Stow JL (2007). “EGF induces macropinocytosis and SNX1-modulated recycling of E-cadherin.” Journal of Cell Science 120(10): 1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buckley CM and King JS (2017). “Drinking problems: mechanisms of macropinosome formation and maturation.” The FEBS Journal 284(22): 3778–3790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buckley CM, Pots H, Gueho A, Vines JH, Munn CJ, Phillips BA, Gilsbach B, Traynor D, Nikolaev A, Soldati T, Parnell AJ, Kortholt A and King JS (2020). “Coordinated Ras and Rac Activity Shapes Macropinocytic Cups and Enables Phagocytosis of Geometrically Diverse Bacteria.” Curr Biol 30(15): 2912–2926.e2915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Canton J (2018). “Macropinocytosis: New Insights Into Its Underappreciated Role in Innate Immune Cell Surveillance.” Frontiers in Immunology 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cao Y, Wang X, Li Y, Evers M, Zhang H and Chen X (2019). “Extracellular and macropinocytosis internalized ATP work together to induce epithelial–mesenchymal transition and other early metastatic activities in lung cancer.” Cancer Cell International 19(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charpentier JC, Chen D, Lapinski PE, Turner J, Grigorova I, Swanson JA and King PD (2020). “Macropinocytosis drives T cell growth by sustaining the activation of mTORC1.” Nature Communications 11(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen J-J, Bozza WP, Di X, Zhang Y, Hallett W and Zhang B (2014). “H-Ras regulation of TRAIL death receptor mediated apoptosis.” 5(13): 5125–5137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chithrani BD, Ghazani AA and Chan WC (2006). “Determining the size and shape dependence of gold nanoparticle uptake into mammalian cells.” Nano Lett 6(4): 662–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Commisso C (2019). “The pervasiveness of macropinocytosis in oncological malignancies.” Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences 374(1765): 20180153–20180153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Commisso C, Davidson SM, Soydaner-Azeloglu RG, Parker SJ, Kamphorst JJ, Hackett S, Grabocka E, Nofal M, Drebin JA, Thompson CB, Rabinowitz JD, Metallo CM, Vander Heiden MG and Bar-Sagi D (2013). “Macropinocytosis of protein is an amino acid supply route in Ras-transformed cells.” 497(7451): 633–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Commisso C and Debnath J (2018). “Macropinocytosis Fuels Prostate Cancer.” Cancer Discovery 8(7): 800–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Commisso C, Flinn RJ and Bar-Sagi D (2014). “Determining the macropinocytic index of cells through a quantitative image-based assay.” 9(1): 182–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Conner SD and Schmid SL (2003). “Regulated portals of entry into the cell.” Nature 422(6927): 37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dausend J, Musyanovych A, Dass M, Walther P, Schrezenmeier H, Landfester K and Mailänder V (2008). “Uptake mechanism of oppositely charged fluorescent nanoparticles in HeLa cells.” Macromol Biosci 8(12): 1135–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Carvalho TMU, Barrias ES and de Souza W (2015). “Macropinocytosis: a pathway to protozoan infection.” Frontiers in Physiology 6(106). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Winde CM, Munday C and Acton SE (2020). “Molecular mechanisms of dendritic cell migration in immunity and cancer.” Medical Microbiology and Immunology 209(4): 515–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dharmawardhane S, Sanders LC, Martin SS, Daniels RH and Bokoch GM (1997). “Localization of p21- Activated Kinase 1 (PAK1) to Pinocytic Vesicles and Cortical Actin Structures in Stimulated Cells.” Journal of Cell Biology 138(6): 1265–1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dharmawardhane S, Schürmann A, Sells MA, Chernoff J, Schmid SL and Bokoch GM (2000). “Regulation of Macropinocytosis by p21-activated Kinase-1.” Molecular Biology of the Cell 11(10): 3341–3352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doherty GJ and McMahon HT (2009). “Mechanisms of Endocytosis.” Annual Review of Biochemistry 78(1): 857–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Donaldson JG (2019). “Macropinosome formation, maturation and membrane recycling: lessons from clathrin- independent endosomal membrane systems.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 374(1765): 20180148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edwards JG (1925). “Formation of Food-Cups in Amoeba Induced by Chemicals.” 48(4): 236. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Egami Y, Taguchi T, Maekawa M, Arai H and Araki N (2014). “Small GTPases and phosphoinositides in the regulatory mechanisms of macropinosome formation and maturation.” Frontiers in Physiology 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elechalawar CK, Hossen MN, McNally L, Bhattacharya R and Mukherjee P (2020). “Analysing the nanoparticle-protein corona for potential molecular target identification.” J Control Release 322: 122–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feliciano WD, Yoshida S, Straight SW and Swanson JA (2011). “Coordination of the Rab5 cycle on macropinosomes.” Traffic (Copenhagen, Denmark) 12(12): 1911–1922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Finicle BT, Jayashankar V and Edinger AL (2018). “Nutrient scavenging in cancer.” Nature Reviews Cancer 18(10): 619–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Foroozandeh P and Aziz AA (2018). “Insight into Cellular Uptake and Intracellular Trafficking of Nanoparticles.” Nanoscale Res Lett 13(1): 339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Francis CL, Ryan TA, Jones BD, Smith SJ and Falkow S (1993). “Ruffles induced by Salmonella and other stimuli direct macropinocytosis of bacteria.” Nature 364(6438): 639–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frohlich E (2012). “The role of surface charge in cellular uptake and cytotoxicity of medical nanoparticles.” Int J Nanomedicine 7: 5577–5591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fujii M, Kawai K, Egami Y and Araki N (2013). “Dissecting the roles of Rac1 activation and deactivation in macropinocytosis using microscopic photo-manipulation.” Scientific Reports 3(1): 2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.García-Pérez BE, De la Cruz-López JJ, Castañeda-Sánchez JI, Muñóz-Duarte AR, Hernández-Pérez AD, Villegas-Castrejón H, García-Latorre E, Caamal-Ley A and Luna-Herrera J (2012). “Macropinocytosis is responsible for the uptake of pathogenic and non-pathogenic mycobacteria by B lymphocytes (Raji cells).” BMC microbiology 12: 246–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garrett WS, Chen L-M, Kroschewski R, Ebersold M, Turley S, Trombetta S, Galán JE and Mellman I (2000). “Developmental Control of Endocytosis in Dendritic Cells by Cdc42.” Cell 102(3): 325–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Giri K, Shameer K, Zimmermann MT, Saha S, Chakraborty PK, Sharma A, Arvizo RR, Madden BJ, McCormick DJ, Kocher JP, Bhattacharya R and Mukherjee P (2014). “Understanding protein-nanoparticle interaction: a new gateway to disease therapeutics.” Bioconjug Chem 25(6): 1078–1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gold S, Monaghan P, Mertens P and Jackson T (2010). “A clathrin independent macropinocytosis-like entry mechanism used by bluetongue virus-1 during infection of BHK cells.” PLoS One 5(6): e11360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goodman CM, McCusker CD, Yilmaz T and Rotello VM (2004). “Toxicity of gold nanoparticles functionalized with cationic and anionic side chains.” Bioconjug Chem 15(4): 897–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ha KD, Bidlingmaier SM and Liu B (2016). “Macropinocytosis Exploitation by Cancers and Cancer Therapeutics.” Frontiers in Physiology 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hagiwara M and Nakase I (2018). “Epidermal growth factor induced macropinocytosis directs branch formation of lung epithelial cells.” Biochem Biophys Res Commun 507(1–4): 297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hobbs GA and Der CJ (2020). “Binge Drinking: Macropinocytosis Promotes Tumorigenic Growth of RASMutant Cancers.” Trends Biochem Sci 45(6): 459–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hodakoski C, Hopkins BD, Zhang G, Su T, Cheng Z, Morris R, Rhee KY, Goncalves MD and Cantley LC (2019). “Rac-Mediated Macropinocytosis of Extracellular Protein Promotes Glucose Independence in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer.” Cancers 11(1): 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hoeller O, Bolourani P, Clark J, Stephens LR, Hawkins PT, Weiner OD, Weeks G and Kay RR (2013). “Two distinct functions for PI3-kinases in macropinocytosis.” Journal of Cell Science 126(18): 4296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hoon J-L, Wong W-K and Koh C-G (2012). “Functions and Regulation of Circular Dorsal Ruffles.” Molecular and Cellular Biology 32(21): 4246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hossen MN, Elechalawar CK, Sjoelund V, Moore K, Mannel R, Bhattacharya R and Mukherjee P (2021). “Experimental conditions influence the formation and composition of the corona around gold nanoparticles.” Cancer Nanotechnology 12(1): 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hossen MN, Wang L, Chinthalapally HR, Robertson JD, Fung KM, Wilhelm S, Bieniasz M, Bhattacharya R and Mukherjee P (2020). “Switching the intracellular pathway and enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of small interfering RNA by auroliposome.” Sci Adv 6(30): eaba5379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Humphreys D, Davidson AC, Hume PJ, Makin LE and Koronakis V (2013). “Arf6 coordinates actin assembly through the WAVE complex, a mechanism usurped by Salmonella to invade host cells.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110(42): 16880–16885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ivanov AI (2008). Pharmacological Inhibition of Endocytic Pathways: Is It Specific Enough to Be Useful? Exocytosis and Endocytosis. A. I. Ivanov. Totowa, NJ, Humana Press: 15–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jiang X, Dausend J, Hafner M, Musyanovych A, Rocker C, Landfester K, Mailander V and Nienhaus GU (2010). “Specific effects of surface amines on polystyrene nanoparticles in their interactions with mesenchymal stem cells.” Biomacromolecules 11(3): 748–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Johannes L and Lamaze C (2002). “Clathrin-Dependent or Not: Is It Still the Question?” Traffic 3(7): 443–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kälin S, Amstutz B, Gastaldelli M, Wolfrum N, Boucke K, Havenga M, DiGennaro F, Liska N, Hemmi S and Greber UF (2010). “Macropinocytotic Uptake and Infection of Human Epithelial Cells with Species B2 Adenovirus Type 35.” Journal of Virology 84(10): 5336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kamphorst JJ, Nofal M, Commisso C, Hackett SR, Lu W, Grabocka E, Vander Heiden MG, Miller G, Drebin JA, Bar-Sagi D, Thompson CB and Rabinowitz JD (2015). “Human Pancreatic Cancer Tumors Are Nutrient Poor and Tumor Cells Actively Scavenge Extracellular Protein.” Cancer Research 75(3): 544–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.King JS and Kay RR (2019). “The origins and evolution of macropinocytosis.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 374(1765): 20180158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kirchhausen T (2000). “Clathrin.” Annual Review of Biochemistry 69(1): 699–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Koehring V (1930). “The neutral-red reaction.” Journal of Morphology 49(1): 45–137. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Koivusalo M, Welch C, Hayashi H, Scott CC, Kim M, Alexander T, Touret N, Hahn KM and Grinstein S (2010). “Amiloride inhibits macropinocytosis by lowering submembranous pH and preventing Rac1 and Cdc42 signaling.” The Journal of cell biology 188(4): 547–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Koumakpayi IH, Le Page C, Delvoye N, Saad F and Mes-Masson A-M (2011). “Macropinocytosis inhibitors and Arf6 regulate ErbB3 nuclear localization in prostate cancer cells.” 50(11): 901–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lammel T, Mackevica A, Johansson BR and Sturve J (2019). “Endocytosis, intracellular fate, accumulation, and agglomeration of titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles in the rainbow trout liver cell line RTL-W1.” Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 26(15): 15354–15372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lanzavecchia A (1990). “Receptor-Mediated Antigen Uptake and its Effect on Antigen Presentation to Class II- Restricted T Lymphocytes.” Annual Review of Immunology 8(1): 773–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lee CHR, Mohamed Hussain K and Chu JJH (2019). “Macropinocytosis dependent entry of Chikungunya virus into human muscle cells.” PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 13(8): e0007610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lee J-H, Pasquarella JR and Kalejta RF (2019). “Cell Line Models for Human Cytomegalovirus Latency Faithfully Mimic Viral Entry by Macropinocytosis and Endocytosis.” Journal of Virology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lewis WH (1931). “Pinocytosis.” Bulletin of the Johns Hopkins Hospital 49: 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lewis WH (1937). “Pinocytosis by Malignant Cells.” The American Journal of Cancer 29(4): 666. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu NQ, Lossinsky AS, Popik W, Li X, Gujuluva C, Kriederman B, Roberts J, Pushkarsky T, Bukrinsky M, Witte M, Weinand M and Fiala M (2002). “Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 enters brain microvascular endothelia by macropinocytosis dependent on lipid rafts and the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway.” J Virol 76(13): 6689–6700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu Z and Roche PA (2015). “Macropinocytosis in phagocytes: regulation of MHC class-II-restricted antigen presentation in dendritic cells.” 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lou J, Low-Nam ST, Kerkvliet JG and Hoppe AD (2014). “Delivery of CSF-1R to the lumen of macropinosomes promotes its destruction in macrophages.” Journal of cell science 127(Pt 24): 5228–5239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lovric J, Bazzi HS, Cuie Y, Fortin GR, Winnik FM and Maysinger D (2005). “Differences in subcellular distribution and toxicity of green and red emitting CdTe quantum dots.” J Mol Med (Berl) 83(5): 377–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mack NA, Whalley HJ, Castillo-Lluva S and Malliri A (2011). “The diverse roles of Rac signaling in tumorigenesis.” 10(10): 1571–1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Marsh M (1999). “The Structural Era of Endocytosis.” 285(5425): 215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mast SO and Doyle WL (1933). “Ingestion of fluid by Amoeba.” 20(1): 555–560. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Maxson ME, Sarantis H, Volchuk A, Brumell JH and Grinstein S (2020). “Rab5 regulates macropinosome closure through recruitment of the inositol 5-phosphatases OCRL/Inpp5b and the hydrolysis of PtdIns(4,5)P<sub>2</sub>.” bioRxiv: 2020.2006.2008.139436. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Meier O, Boucke K, Hammer SV, Keller S, Stidwill RP, Hemmi S and Greber UF (2002). “Adenovirus triggers macropinocytosis and endosomal leakage together with its clathrin-mediated uptake.” J Cell Biol 158(6): 1119–1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mercer J and Helenius A (2008). “Vaccinia Virus Uses Macropinocytosis and Apoptotic Mimicry to Enter Host Cells.” Science 320(5875): 531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mercer J and Helenius A (2009). “Virus entry by macropinocytosis.” Nature Cell Biology 11(5): 510–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mercer J, Knebel S, Schmidt FI, Crouse J, Burkard C and Helenius A (2010). “Vaccinia virus strains use distinct forms of macropinocytosis for host-cell entry.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107(20): 9346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mercer J, Schelhaas M and Helenius A (2010). “Virus Entry by Endocytosis.” Annual Review of Biochemistry 79(1): 803–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Michalopoulou E, Auciello FR, Bulusu V, Strachan D, Campbell AD, Tait-Mulder J, Karim SA, Morton JP, Sansom OJ and Kamphorst JJ (2020). “Macropinocytosis Renders a Subset of Pancreatic Tumor Cells Resistant to mTOR Inhibition.” Cell reports 30(8): 2729–2742.e2724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Morishita S, Wada N, Fukuda M and Nakamura T (2019). “Rab5 activation on macropinosomes requires ALS2, and subsequent Rab5 inactivation through ALS2 detachment requires active Rab7.” FEBS Letters 593(2): 230–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mosesson Y, Mills GB and Yarden Y (2008). “Derailed endocytosis: an emerging feature of cancer.” Nat Rev Cancer 8(11): 835–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nakase I, Kobayashi NB, Takatani-Nakase T and Yoshida T (2015). “Active macropinocytosis induction by stimulation of epidermal growth factor receptor and oncogenic Ras expression potentiates cellular uptake efficacy of exosomes.” Scientific Reports 5(1): 10300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nobes C and Marsh M (2000). “Dendritic cells: new roles for Cdc42 and Rac in antigen uptake?” Curr Biol 10(20): R739–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nofal M, Zhang K, Han S and Rabinowitz JD (2017). “mTOR Inhibition Restores Amino Acid Balance in Cells Dependent on Catabolism of Extracellular Protein.” Molecular Cell 67(6): 936–946.e935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Palm W (2019). “Metabolic functions of macropinocytosis.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 374(1765): 20180285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Palm W, Park Y, Wright K, Pavlova NN, Tuveson DA and Thompson CB (2015). “The Utilization of Extracellular Proteins as Nutrients Is Suppressed by mTORC1.” Cell 162(2): 259–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pellegatti P, Raffaghello L, Bianchi G, Piccardi F, Pistoia V and Di Virgilio F (2008). “Increased level of extracellular ATP at tumor sites: in vivo imaging with plasma membrane luciferase.” PloS one 3(7): e2599–e2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pupo E, Avanzato D, Middonti E, Bussolino F and Lanzetti L (2019). “KRAS-Driven Metabolic Rewiring Reveals Novel Actionable Targets in Cancer.” Frontiers in Oncology 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Qian Y, Wang X, Liu Y, Li Y, Colvin RA, Tong L, Wu S and Chen X (2014). “Extracellular ATP is internalized by macropinocytosis and induces intracellular ATP increase and drug resistance in cancer cells.” Cancer Lett 351(2): 242–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Racoosin EL and Swanson JA (1992). “M-CSF-induced macropinocytosis increases solute endocytosis but not receptor-mediated endocytosis in mouse macrophages.” J Cell Sci 102 ( Pt 4): 867–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Recouvreux MV and Commisso C (2017). “Macropinocytosis: A Metabolic Adaptation to Nutrient Stress in Cancer.” Frontiers in Endocrinology 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Redelman-Sidi G, Iyer G, Solit DB and Glickman MS (2013). “Oncogenic activation of Pak1-dependent pathway of macropinocytosis determines BCG entry into bladder cancer cells.” Cancer research 73(3): 1156–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Redka D. y. S., Gütschow M, Grinstein S and Canton J (2018). “Differential ability of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory macrophages to perform macropinocytosis.” Molecular Biology of the Cell 29(1): 53–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Reif R, Adawy A, Vartak N, Schröder J, Günther G, Ghallab A, Schmidt M, Schormann W and Hengstler JG (2016). “Activated ErbB3 Translocates to the Nucleus via Clathrin-independent Endocytosis, Which Is Associated with Proliferating Cells.” 291(8): 3837–3847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rizopoulos Z, Balistreri G, Kilcher S, Martin CK, Syedbasha M, Helenius A and Mercer J (2015). “Vaccinia Virus Infection Requires Maturation of Macropinosomes.” Traffic (Copenhagen, Denmark) 16(8): 814–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Rosales C and Uribe-Querol E (2017). “Phagocytosis: A Fundamental Process in Immunity.” BioMed Research International 2017: 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sabourian P, Yazdani G, Ashraf SS, Frounchi M, Mashayekhan S, Kiani S and Kakkar A (2020). “Effect of Physico-Chemical Properties of Nanoparticles on Their Intracellular Uptake.” Int J Mol Sci 21(21). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Salloum G, Jakubik CT, Erami Z, Heitz SD, Bresnick AR and Backer JM (2019). “PI3Kβ is selectively required for growth factor-stimulated macropinocytosis.” Journal of Cell Science 132(16): jcs231639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sallusto F (1995). “Dendritic cells use macropinocytosis and the mannose receptor to concentrate macromolecules in the major histocompatibility complex class II compartment: downregulation by cytokines and bacterial products.” Journal of Experimental Medicine 182(2): 389–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Schaeffer AA (1916). “CONCERNING THE SPECIES AMOEligBA PROTEUS.” Science 44(1135): 468–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Schmees C, Villaseñor R, Zheng W, Ma H, Zerial M, Heldin CH and Hellberg C (2012). “Macropinocytosis of the PDGF β-receptor promotes fibroblast transformation by H-RasG12V.” Molecular Biology of the Cell 23(13): 2571–2582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Schmid EM and McMahon HT (2007). “Integrating molecular and network biology to decode endocytosis.” 448(7156): 883–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Schulz AM, Stutte S, Hogl S, Luckashenak N, Dudziak D, Leroy C, Forné I, Imhof A, Müller SA, Brakebusch CH, Lichtenthaler SF and Brocker T (2015). “Cdc42-dependent actin dynamics controls maturation and secretory activity of dendritic cells.” Journal of Cell Biology 211(3): 553–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z and Jemal A (2014). “Cancer statistics, 2014.” CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 64(1): 9–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Singh A, Greninger P, Rhodes D, Koopman L, Violette S, Bardeesy N and Settleman J (2009). “A gene expression signature associated with “K-Ras addiction” reveals regulators of EMT and tumor cell survival.” Cancer cell 15(6): 489–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sussman R and Sussman M (1967). “Cultivation of Dictyostelium discoideum in axenic medium.” Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 29(1): 53–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Swanson JA (2008). “Shaping cups into phagosomes and macropinosomes.” Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 9(8): 639–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Swanson JA and King JS (2019). “The breadth of macropinocytosis research.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 374(1765): 20180146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Swanson JA and Watts C (1995). “Macropinocytosis.” Trends in Cell Biology 5(11): 424–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Tang W, Tam JHK, Seah C, Chiu J, Tyrer A, Cregan SP, Meakin SO and Pasternak SH (2015). “Arf6 controls beta-amyloid production by regulating macropinocytosis of the Amyloid Precursor Protein to lysosomes.” Molecular Brain 8(1): 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Tate JG, Bamford S, Jubb HC, Sondka Z, Beare DM, Bindal N, Boutselakis H, Cole CG, Creatore C, Dawson E, Fish P, Harsha B, Hathaway C, Jupe SC, Kok CY, Noble K, Ponting L, Ramshaw CC, Rye CE, Speedy HE, Stefancsik R, Thompson SL, Wang S, Ward S, Campbell PJ and Forbes SA (2018). “COSMIC: the Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer.” Nucleic Acids Research 47(D1): D941–D947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Valdivia A, Goicoechea SM, Awadia S, Zinn A and Garcia-Mata R (2017). “Regulation of circular dorsal ruffles, macropinocytosis, and cell migration by RhoG and its exchange factor, Trio.” Molecular biology of the cell 28(13): 1768–1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wang JTH, Kerr MC, Karunaratne S, Jeanes A, Yap AS and Teasdale RD (2010). “The SNX-PX-BAR family in macropinocytosis: the regulation of macropinosome formation by SNX-PX-BAR proteins.” PloS one 5(10): e13763–e13763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wang JTH, Teasdale RD and Liebl D (2014). “Macropinosome quantitation assay.” MethodsX 1: 36–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Waters AM and Der CJ (2018). “KRAS: The Critical Driver and Therapeutic Target for Pancreatic Cancer.” Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine 8(9): a031435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Watts DJ and Ashworth JM (1970). “Growth of myxamoebae of the cellular slime mould Dictyostelium discoideum in axenic culture.” Biochemical Journal 119(2): 171–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Weerasekara VK, Patra KC and Bardeesy N (2019). “EGFR Pathway Links Amino Acid Levels and Induction of Macropinocytosis.” Developmental Cell 50(3): 261–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Welliver TP, Chang SL, Linderman JJ and Swanson JA (2011). “Ruffles limit diffusion in the plasma membrane during macropinosome formation.” Journal of Cell Science 124(23): 4106–4114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.West MA (2004). “Enhanced Dendritic Cell Antigen Capture via Toll-Like Receptor-Induced Actin Remodeling.” Science 305(5687): 1153–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.West MA, Bretscher MS and Watts C (1989). “Distinct endocytotic pathways in epidermal growth factor- stimulated human carcinoma A431 cells.” Journal of Cell Biology 109(6): 2731–2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.White E (2013). “Exploiting the bad eating habits of Ras-driven cancers.” Genes Dev 27(19): 2065–2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Williams TD, Paschke PI and Kay RR (2019). “Function of small GTPases in Dictyostelium macropinocytosis.” Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences 374(1765): 20180150–20180150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Williamson CD and Donaldson JG (2019). “Arf6, JIP3, and dynein shape and mediate macropinocytosis.” Molecular Biology of the Cell 30(12): 1477–1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Wolfgang CL, Herman JM, Laheru DA, Klein AP, Erdek MA, Fishman EK and Hruban RH (2013). “Recent progress in pancreatic cancer.” CA Cancer J Clin 63(5): 318–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Xiong X, Rao G, Roy RV, Zhang Y, Means N, Dey A, Tsaliki M, Saha S, Bhattacharyya S, Dhar Dwivedi SK, Rao CV, McCormick DJ, Dhanasekaran D, Ding K, Gillies E, Zhang M, Yang D, Bhattacharya R and Mukherjee P (2020). “Ubiquitin-binding associated protein 2 regulates KRAS activation and macropinocytosis in pancreatic cancer.” The FASEB Journal 34(9): 12024–12039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Yasen A, Herrera R, Rosbe K, Lien K and Tugizov SM (2018). “HIV internalization into oral and genital epithelial cells by endocytosis and macropinocytosis leads to viral sequestration in the vesicles.” Virology 515: 92–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Yoshida S, Pacitto R, Inoki K and Swanson J (2018). “Macropinocytosis, mTORC1 and cellular growth control.” Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 75(7): 1227–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Yoshida S, Pacitto R, Sesi C, Kotula L and Swanson JA (2018). “Dorsal Ruffles Enhance Activation of Akt by Growth Factors.” bioRxiv: 324434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Zaki NM, Nasti A and Tirelli N (2011). “Nanocarriers for cytoplasmic delivery: cellular uptake and intracellular fate of chitosan and hyaluronic acid-coated chitosan nanoparticles in a phagocytic cell model.” Macromol Biosci 11(12): 1747–1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]