Abstract

Background

Child and adolescent overweight and obesity have increased globally, and are associated with short‐ and long‐term health consequences.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy of diet, physical activity and behavioural interventions delivered to parents only for the treatment of overweight and obesity in children aged 5 to 11 years.

Search methods

We performed a systematic literature search of databases including the Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL and LILACS as well trial registers. We checked references of identified trials and systematic reviews. We applied no language restrictions. The date of the last search was March 2015 for all databases.

Selection criteria

We selected randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of diet, physical activity and behavioural interventions delivered to parents only for treating overweight or obesity in children aged 5 to 11 years.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trials for risk of bias and evaluated overall study quality using the GRADE instrument. Where necessary, we contacted authors for additional information.

Main results

We included 20 RCTs, including 3057 participants. The number of participants ranged per trial between 15 and 645. Follow‐up ranged between 24 weeks and two years. Eighteen trials were parallel RCTs and two were cluster RCTs. Twelve RCTs had two comparisons and eight RCTs had three comparisons. The interventions varied widely; the duration, content, delivery and follow‐up of the interventions were heterogeneous. The comparators also differed. This review categorised the comparisons into four groups: parent‐only versus parent‐child, parent‐only versus waiting list controls, parent‐only versus minimal contact interventions and parent‐only versus other parent‐only interventions.

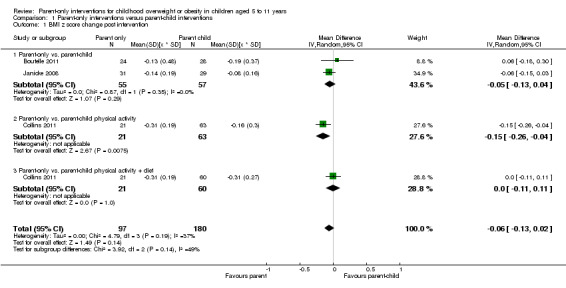

Trial quality was generally low with a large proportion of trials rated as high risk of bias on individual risk of bias criteria.

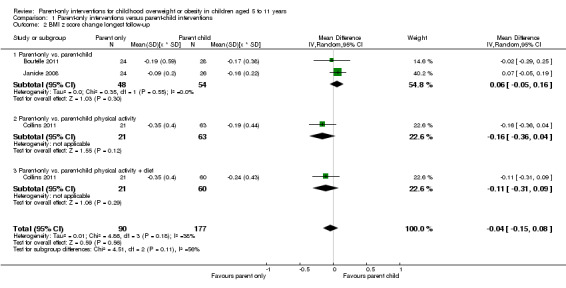

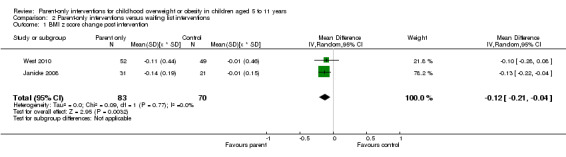

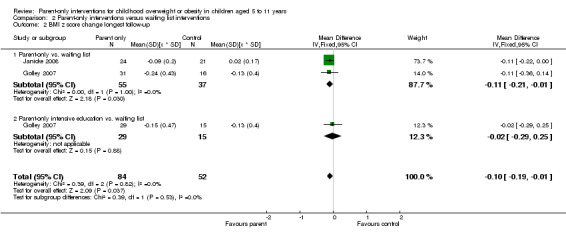

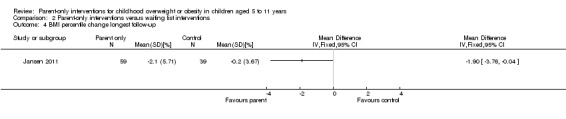

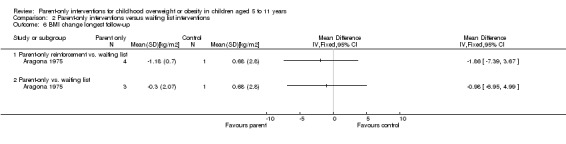

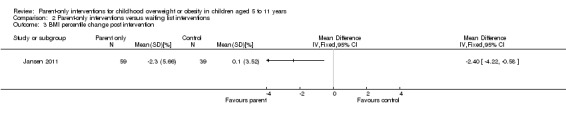

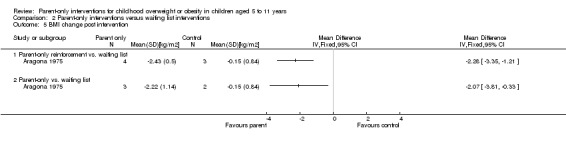

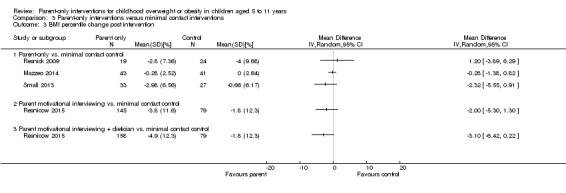

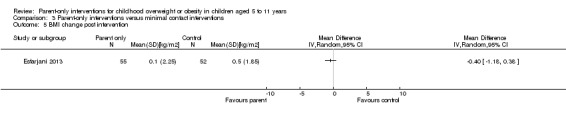

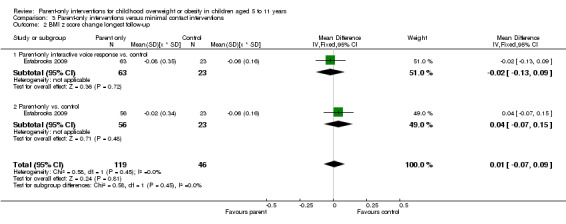

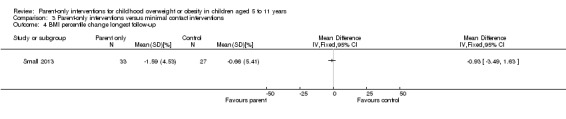

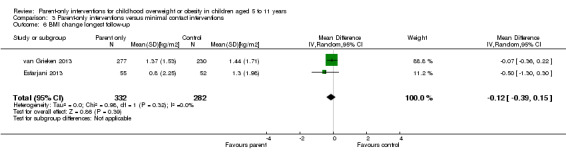

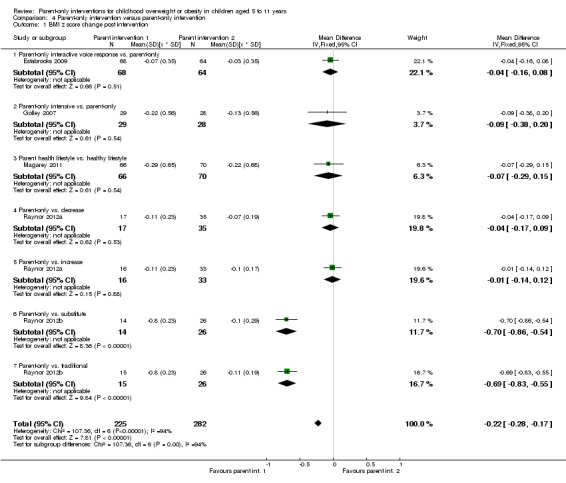

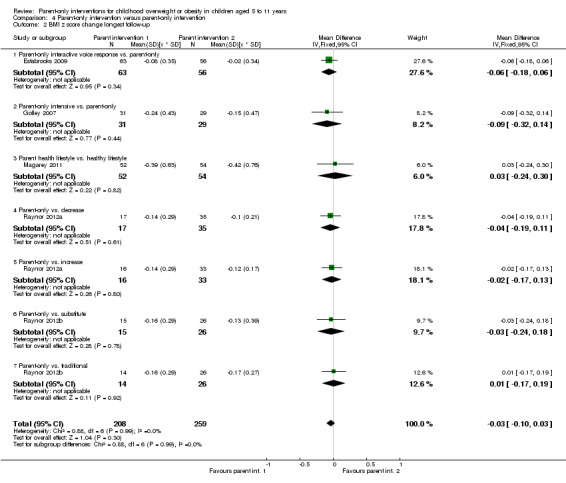

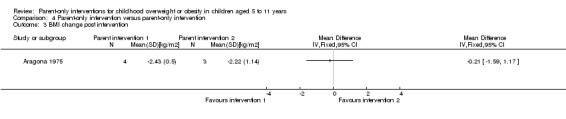

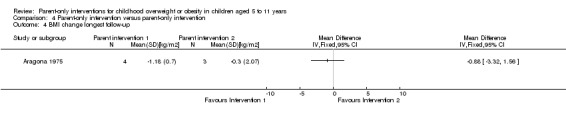

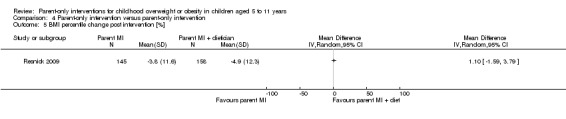

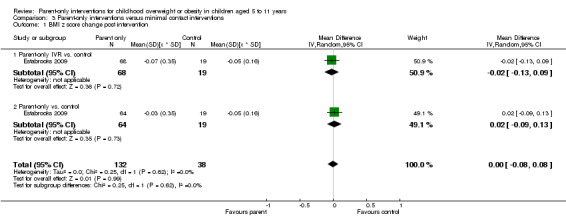

In trials comparing a parent‐only intervention with a parent‐child intervention, the body mass index (BMI) z score change showed a mean difference (MD) at the longest follow‐up period (10 to 24 months) of ‐0.04 (95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.15 to 0.08); P = 0.56; 267 participants; 3 trials; low quality evidence. In trials comparing a parent‐only intervention with a waiting list control, the BMI z score change in favour of the parent‐only intervention at the longest follow‐up period (10‐12 months) had an MD of ‐0.10 (95% CI ‐0.19 to ‐0.01); P = 0.04; 136 participants; 2 trials; low quality evidence. BMI z score change of parent‐only interventions when compared with minimal contact control interventions at the longest follow‐up period (9 to 12 months) showed an MD of 0.01 (95% CI ‐0.07 to 0.09); P = 0.81; 165 participants; 1 trial; low quality evidence. There were few similarities between interventions and comparators across the included trials in the parent‐only intervention versus other parent‐only interventions and we did not pool these data. Generally, these trials did not show substantial differences between their respective parent‐only groups on BMI outcomes.

Other outcomes such as behavioural measures, parent‐child relationships and health‐related quality of life were reported inconsistently. Adverse effects of the interventions were generally not reported, two trials stated that there were no serious adverse effects. No trials reported on all‐cause mortality, morbidity or socioeconomic effects.

All results need to be interpreted cautiously because of their low quality, the heterogeneous interventions and comparators, and the high rates of non‐completion.

Authors' conclusions

Parent‐only interventions may be an effective treatment option for overweight or obese children aged 5 to 11 years when compared with waiting list controls. Parent‐only interventions had similar effects compared with parent‐child interventions and compared with those with minimal contact controls. However, the evidence is at present limited; some of the trials had a high risk of bias with loss to follow‐up being a particular issue and there was a lack of evidence for several important outcomes. The systematic review has identified 10 ongoing trials that have a parent‐only arm, which will contribute to future updates. These trials will improve the robustness of the analyses by type of comparator, and may permit subgroup analysis by intervention component and the setting. Trial reports should provide adequate details about the interventions to be replicated by others. There is a need to conduct and report cost‐effectiveness analyses in future trials in order to establish whether parent‐only interventions are more cost‐effective than parent‐child interventions.

Plain language summary

Parent‐only interventions for childhood overweight or obesity in children aged 5 to 11 years

Review question

How effective are diet, physical activity and behavioural interventions delivered to parents only in reducing the weight of overweight and obese children?

Background

Across the world more children are becoming overweight and obese. These children are more likely to suffer from health problems as children and in later life. Parents can play an important role in determining what their children eat. More information is needed about whether helping parents to make changes to their family's diet and lifestyle will treat this problem.

Study characteristics

We found 20 randomised controlled trials (clinical studies where people are randomly put into one of two or more treatment groups) comparing diet, physical activity and behavioural (where habits are changed or improved) treatments (interventions) to a variety of control groups (who did not receive treatment) delivered to parents only of 3057 children aged 5 to 11 years. There were few similarities between the trials in the nature and types of interventions used. We grouped the trials by the type of comparisons. Our systematic review reported on the effects of the parent‐only interventions compared with parent and child interventions, waiting list controls (where the intervention was delayed until the end of the trial), other interventions with only minimal information or contact and other types of parent‐only interventions. The children in the included trials were monitored (called follow‐up) for between six months and two years. This evidence is up to date as of March 2015.

Key results

The most reported outcome was the body mass index (BMI). This is a measure of body fat and is calculated by dividing weight (in kilograms) by the square of the body height measured in metres (kg/m2). The studies measured BMI in ways that took account of gender, weight and height as the children grew older (such as the BMI z score and the BMI percentile).

When compared with a waiting list control, there was limited evidence that parental interventions helped to reduce BMI. In looking at the longest follow‐up periods of the included trials, we did not find firm evidence of an advantage or disadvantage of parent‐only interventions when compared with either parent and child interventions, or when compared with limited information. Our review found very little information about how different types of parental interventions compared. No trial reported on death from any cause, illness or socioeconomic effects (such as whether parent‐only interventions are lower in costs compared with parent and child interventions). Two trials reported no serious side effects and the rest of the trials did not report whether side effects occurred or not. Information on parent‐child relationships and health‐related quality of life was rarely reported.

Quality of the evidence

The overall quality of the evidence was low, mainly because there were just a few trials per measurement or the number of the included children was small. In addition, many children left the trials before they had finished.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Parent‐only interventions versus parent‐child interventions for childhood overweight or obesity.

| Parent‐only interventions vs. parent‐child interventions for childhood overweight or obesity | ||||||

|

Population: children with overweight or obesity Settings: outpatients; community/university Intervention: parent‐only interventions Comparison: parent‐child interventions | ||||||

| Outcomes | Parent‐child | Parent‐only | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (trials) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

|

BMI z score change (x * SD) Follow‐up: 40‐104 weeks |

The mean BMI z score change ranged across control groups from ‐0.16 to ‐0.24 | The mean BMI z score change in the intervention groups was 0.04 lower (0.15 lower to 0.08 higher) | ‐ | 267 (3) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | Lower scores indicate improved weight loss |

| Adverse events | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | No trials reported adverse events |

| Health‐related quality of life | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | No trials reported health‐related quality of life |

| All‐cause mortality | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | No trials reported all‐cause mortality |

| Morbidity | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | No trials reported morbidity |

| Parent‐child relationship or assessment of parenting | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | No trials reported outcomes assessing parent‐child relationships or an assessment of parenting |

| Socioeconomic effects | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | No trials reported socioeconomic effects |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across trials) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).

BMI: body mass index; CI: confidence interval; SD: standard deviation. GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

"A BMI z score or standard deviation score indicates how many units (of the standard deviation) a child's BMI is above or below the average BMI value for their age group and sex. For instance, a z score of 1.5 indicates that a child' is 1.5 standard deviations above the average value, and a z score of ‐1.5 indicates a child is 1.5 standard deviations below the average value" (Noo NHS 2011).

aDowngraded by one level because of serious risk of attrition bias and one level for serious imprecision (see Appendix 9).

Summary of findings 2. Parent‐only interventions versus waiting list control for childhood overweight or obesity.

| Parent‐only interventions vs. waiting list control for childhood overweight or obesity | ||||||

|

Population: children with overweight or obesity Settings: outpatients; community Intervention: parent‐only interventions Comparison: waiting list control | ||||||

| Outcomes | Waiting list | Parent‐only | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (trials) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

|

BMI z score change (x * SD) Follow‐up: 40‐48 weeks |

The mean BMI z score change ranged across control groups from ‐0.13 to 0.02 | The mean BMI z score change in the intervention groups was 0.1 lower (0.19 lower to 0.01 lower) | ‐ | 136 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | Lower scores indicate improved weight loss |

| Adverse events | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | No trials reported adverse events |

| Health‐related quality of life | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | No trials reported health‐related quality of life |

| All‐cause mortality | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | No trials reported all‐cause mortality |

| Morbidity | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | No trials reported morbidity |

|

Parent‐child relationship or assessment of parenting (parenting scale (PS), 30 items, scored from 1 to 7; lower scores indicate more effective parental discipline practices) Follow‐up: 12 weeks |

The mean PS score for the control group was 3.4 | The mean PS score in the intervention group was 0.6 points lower | ‐ | 101 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | ‐ |

| Socioeconomic effects | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | No trials reported socioeconomic effects |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across trials) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).

BMI: body mass index; CI: confidence interval; PS: parenting scale; SD: standard deviation. GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

"A BMI z score or standard deviation score indicates how many units (of the standard deviation) a child's BMI is above or below the average BMI value for their age group and sex. For instance, a z score of 1.5 indicates that a child' is 1.5 standard deviations above the average value, and a z score of ‐1.5 indicates a child is 1.5 standard deviations below the average value" (Noo NHS 2011).

aDowngraded by one level because of serious risk of attrition bias and one level for serious imprecision (see Appendix 9).

Summary of findings 3. Parent‐only interventions versus minimal contact control for childhood overweight or obesity.

| Parent‐only interventions vs. minimal contact control for childhood overweight or obesity | ||||||

|

Population: children with overweight or obesity Settings: outpatients Intervention: parent‐only interventions Comparison: minimal contact control | ||||||

| Outcomes | Minimal contact | Parent‐only | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (trials) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

|

BMI z score change (x * SD) Follow‐up: 52 weeks |

The mean BMI z score change ranged across control groups from ‐0.06 to ‐0.06 | The mean BMI z score change in the intervention group was 0.01 lower (‐0.07 lower to 0.09 higher) | ‐ | 165 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | Lower scores indicate improved weight loss |

| Adverse events | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | No trials reported adverse events |

|

Health‐related quality of life (Pediatric Health‐Related Quality of Life, scale from 0 to 100; higher scores indicate better HRQoL) Follow‐up: 24 weeks) |

See comment | See comment | See comment | 93 (1) | See comment | No data were presented ('"no improvements in health‐related quality of life") |

| All‐cause mortality | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | No trials reported all‐cause mortality |

| Morbidity | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | No trials reported morbidity |

|

Parent‐child relationship or assessment of parenting (Child Feeding Questionnaire subscale parental concern (total of 7 subscales), score range 3‐15; higher scores indicate greater parental concern) Follow‐up: 12 weeks |

The mean parent concern score was 4.7 in the control group | The mean parent concern score in the intervention group was 0.1 lower. | ‐ | 93 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | ‐ |

| Socioeconomic effects | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | No trials reported socioeconomic effects |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across trials) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).

BMI: body mass index; CI: confidence interval; HRQoL: health‐related quality of life; SD: standard deviation. GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

"A BMI z score or standard deviation score indicates how many units (of the standard deviation) a child's BMI is above or below the average BMI value for their age group and sex. For instance, a z score of 1.5 indicates that a child' is 1.5 standard deviations above the average value, and a z score of ‐1.5 indicates a child is 1.5 standard deviations below the average value" (Noo NHS 2011).

aDowngraded by one level because of serious risk of attrition bias and one level for serious imprecision (see Appendix 9).

Summary of findings 4. Parent‐only interventions versus parent‐only interventions for childhood overweight or obesity.

| Parent‐only interventions vs. parent‐only interventions for childhood overweight or obesity | ||||||

|

Population: children with overweight or obesity Settings: outpatients; university + primary care Intervention: parent‐only interventions Comparison: parent‐only interventions | ||||||

| Outcomes | Parent‐only | Parent‐only | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (trials) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

|

BMI z score change (x * SD) Follow‐up: 12‐24 months |

See comment | See comment | See comment | 467 (5) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | No meta‐analysis because of little consistency between trial interventions and comparators; there were no substantial differences between different parent‐only interventions |

| Adverse events | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | Two trials reported that there were no serious adverse events (Raynor 2012a; Raynor 2012b) |

| Health‐related quality of life | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | No trials reported health‐related quality of life |

| All‐cause mortality | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | No trials reported all‐cause mortality |

| Morbidity | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | No trials reported morbidity |

|

Parent‐child relationship or assessment of parenting (Alabama Parenting Questionnaire, 35 items; higher scores indicate improvement) Follow‐up: 24 months |

See comment | See comment | See comment | 106 (1) | See comment | 1 study assessed parent‐child relationship or assessment of parenting but there were no data for comparisons between intervention groups provided |

| Socioeconomic effects | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | No trials reported socioeconomic effects |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across trials) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).

BMI: body mass index; CI: confidence interval; SD: standard deviation. GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

"A BMI z score or standard deviation score indicates how many units (of the standard deviation) a child's BMI is above or below the average BMI value for their age group and sex. For instance, a z score of 1.5 indicates that a child' is 1.5 standard deviations above the average value, and a z score of ‐1.5 indicates a child is 1.5 standard deviations below the average value" (Noo NHS 2011).

aDowngraded by one level because of serious risk of attrition bias and one level for serious imprecision (see Appendix 9)

Background

The prevalence of overweight and obese children and adolescents has increased throughout the world, presenting a global public health crisis (Ng 2014; WHO 2015a). Although once considered to be a condition affecting only developed countries, rates of paediatric overweight and obesity have started to rise dramatically in some developing countries (Wang 2012). Using the International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) standard definition, the age‐standardised prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents has increased in both developed and developing countries since the mid‐1980s (Cole 2000). In 2013, the prevalence of overweight and obese children and adolescents in developed countries was estimated at 23.8% (95% confidence interval (CI) 22.9 to 24.7)) for boys and 22.6% (95% CI 21.7 to 23.6) for girls. In developing countries, the prevalence was estimated as 12.9% (95% CI 12.3 to 13.5) for boys and 13.4% (95% CI 13.0 to 13.9) for girls (Ng 2014). Very young children are also affected. In 2010, de Onis 2010 used the World Health Organization (WHO) growth standards (WHO 2015b) to estimate that over 42 million children under five years of age were overweight or obese, with approximately 35 million of these children living in developing countries.

Inequalities in overweight and obesity prevalence have also been documented. Generally, socioeconomically disadvantaged children in developed countries (Knai 2012; Shrewsbury 2008), and children of higher socioeconomic status in developing countries (Lobstein 2004; Wang 2012), are at greater risk of becoming overweight. However, this relationship may vary by population demographics (e.g. age, gender, ethnicity), and environment (e.g. country, urbanisation) (Wang 2012). The prevalence of obesity varies by ethnicity, with large data sets showing substantial ethnic variation in English (HSCIC 2015), American (Freedman 2006; Skinner 2014), and New Zealand (Rajput 2014) child populations.

While there is some evidence that the rate of increase in paediatric obesity may be slowing in some developed countries, current levels remain too high, and continue to rise in many developing countries (Olds 2011; Rokholm 2010). However, an additional concern in some developed countries such as the USA (Kelly 2013; Skinner 2014), and England (CMO 2012; Ells 2015), is the rise in severe paediatric obesity. While the IOTF published an international definition for severe paediatric (morbid) obesity in 2012 (Cole 2012), often severe obesity prevalence is reported using country‐specific cut‐off points making international comparisons difficult. However, data from the USA (Skinner 2014), and England (Ells 2015), have shown that the prevalence of severe paediatric obesity varies by socioeconomic status and ethnicity, and may result in a greater risk of adverse cardio‐metabolic events and severe obesity in adulthood (Kelly 2013).

Description of the condition

Childhood overweight and obesity results from an accumulation of excess body fat, and can increase the risk of both short‐ and longer‐term health consequences. Numerous obesity‐related co‐morbidities can develop during childhood, which include muscular skeletal complaints (Paulis 2014); cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, insulin resistance and hyperlipidaemia (Reilly 2003), even in very young children (Bocca 2013); and conditions such as such as sleep apnoea (Narang 2012), asthma (Egan 2013), liver disease, and type 2 diabetes (Daniels 2009; Lobstein 2004). The condition can also affect psychosocial well‐being, with obese young people susceptible to reduced self esteem and health‐related quality of life (Griffiths 2010), and stigmatisation (Puhl 2007; Tang‐Peronard 2008). Evidence also shows that childhood obesity can track into adulthood (Parsons 1999; Singh 2008; Whitaker 1997), and is therefore associated with an increased risk of ill health later in life (Reilly 2011).

Description of the intervention

Given the serious implications associated with childhood and adolescent obesity, effective treatment is imperative. While the fundamental principles of weight management in children and adolescents are the same as adults (i.e. reduced energy intake and increased energy expenditure), the primary aim of treatment (i.e. weight reduction or deceleration of weight gain) and the most suitable intervention approach varies, and is dependent on the child's age and degree of excess weight, among other considerations.

Family‐based interventions combining dietary, physical activity and behavioural components are effective and are considered as the current best practice in the treatment of childhood obesity in children under 12 years of age (Oude Luttikhuis 2009). However, interventions that involve the whole family can be costly, especially with parents and children in separate groups and when not running at full capacity (Upton 2012). Therefore, increased attention is being paid to the possibility of parent‐focused interventions.

Parents have been defined as the 'agents of change' for intervening with children under 12 years of age who are obese (Golan 2004). Several interventions have been developed where parents are targeted solely for the treatment of their child's obesity, thereafter referred to as 'parent‐only' interventions, in which the child is not involved directly with the intervention. Parent‐only interventions vary both by type (e.g. based on parenting courses, cognitive behavioural therapy, behaviour change) and by setting (e.g. community, clinic based).

Adverse effects of the intervention

It is not anticipated that parent‐only interventions will lead to adverse outcomes. However, as with all obesity treatment interventions in children and young people, potential adverse effects should be considered, including effects on linear growth, eating disorders and psychological well‐being.

How the intervention might work

The home environment is important in the aetiology of childhood obesity, with parents playing a large role in food choice and physical activity for their children. In surveys in the US, Wansink estimated that the 'nutritional gatekeeper' (who buys and cooks the food) controls 72% of the food eaten by children, both within and outside the home (Wansink 2006). One systematic review by Clark et al. showed that a high level of parental restriction of snack foods is associated with increased energy intake and weight gain in children (Clark 2007). In contrast, 'covert' control of children's food intake by controlling the home eating environment to limit exposure to unhealthy foods (i.e. not buying unhealthy foods) lows the intake of unhealthy snacks when compared with 'overt' control (i.e. buying the snacks but not allowing access) (Ogden 2006). In terms of physical activity, one systematic review showed that parental support is strongly associated with physical activity levels in children, albeit the influence of parental modelling by being physically active themselves was inconsistent (Gustafson 2006).

Poor family functioning, such as poor communication and high levels of conflict, is also associated with higher risk of obesity in children (Halliday 2014). Authoritative parenting style is associated with lower risk of obesity in children, when compared with other parenting styles (Sleddens 2011).

Due to the importance of the role of parents in the home environment and the importance of parenting styles and skills, parents have been defined as the 'agents of change' in the family for intervening with children under 12 years of age who are obese (Golan 2004). The importance of parents in the change process has led to a questioning of whether children need to be at the intervention. Parent‐only interventions aim to work by giving parents the responsibility for their family's eating and physical activity environment and by increasing parental capacity to implement the lifestyle changes. Trials have assessed whether parent‐only interventions are superior to or equivalent to parent‐child interventions, as well as comparisons with waiting list control.

Why it is important to do this review

The first version of this systematic review was published in 2003 and included analysis of childhood obesity treatment trials published up to July 2001 (Summerbell 2003). The second version was published in 2009 providing an update to the 2003 review (Oude Luttikhuis 2009).

To reflect the rapid growth in this field, the third update to this review has been split across six reviews focusing on the following treatment approaches: surgery; drugs; parent‐only interventions; diet, physical activity and behavioural interventions for young children aged 0 to 4 years; school children aged 5 to 11 years and adolescents aged 12 to 17 years.

The current review examined the effectiveness of interventions in which parents were targeted solely for the treatment of childhood obesity. This review built on two reviews in this area in which parent‐only interventions appeared to be as effective as interventions that adopted the traditional model where the parent and child were both involved in the intervention (Ewald 2014; Jull 2013). Faith 2012 revealed inconsistent evidence that greater parent and adult carer involvement was associated with better child outcomes. This review extended the evidence of effectiveness by including trials that compared parent‐only interventions with parent‐child interventions, waiting list controls, other interventions with only minimal information or contact and other types of parent‐only interventions. These trials were brought together to examine the effectiveness of parent‐only interventions for the treatment of childhood obesity. The review also intended to explore the impact of the type of parent‐only intervention (e.g. focusing on parenting, cognitive behavioural therapy, behaviour change) and the setting (e.g. community, clinic‐based, internet), to determine if any specific approach was more effective for the treatment of childhood obesity.

The results of this current review and other systematic reviews in this series provided information on which to underpin clinical guidelines and health policy on the treatment of childhood overweight or obesity.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy of diet, physical activity and behavioural interventions delivered to parents only for the treatment of overweight and obesity in children aged 5 to 11 years.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Types of participants

Study groups consisted of children with a mean study age of 5 to 11 years at the commencement of the intervention.

Diagnostic criteria

We included overweight or obese children by any classification.

Types of interventions

We planned to investigate the following comparisons of intervention versus control/comparator.

Intervention

Any form of lifestyle intervention with a primary aim to treat overweight or obesity in children (any form of dietary, physical activity, behavioural therapy, or a combination of these delivered as single or multi‐component interventions) directed at the parents as the agents of change (i.e. interventions did not include their children).

Comparator

Usual care, a parent‐child intervention, child only intervention or an alternative concomitant therapy providing it was delivered in the intervention arm.

Concomitant interventions had to be the same in the intervention and comparator groups to establish fair comparisons.

Minimum duration of intervention/follow‐up

Duration of intervention/follow‐up had to be at least six months.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded critically ill children or children with a syndromic cause for their obesity (e.g. Prader‐Willi).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Changes in body mass index (BMI) and body weight.

Adverse events.

Secondary outcomes

Health‐related quality of life and self esteem.

All‐cause mortality.

Morbidity.

Measures of body fat distribution.

Behaviour change.

Participants' views of the intervention.

Parent‐child relationship or assessment of parenting.

Socioeconomic effects by validated measures.

Method and timing of outcome measurement

Changes in BMI (kg/m2) and body weight (kg) measured at baseline, and at least at 6, 12 and 24 months.

Adverse events: defined as an adverse outcome that occurred during or after the intervention but was not necessarily caused by it, and measured at baseline, and at least at 6, 12 and 24 months.

Health‐related quality of life: evaluated by a validated instruments such as the Paediatric Quality of Life Inventory and measured at baseline, and at least at 6, 12 and 24 months.

All‐cause mortality: defined as any death that occurred during or after the intervention and measured at baseline, and at least at 6, 12 and 24 months

Morbidity: defined as illness or harm associated with the intervention and measured at baseline, and at least at 6, 12 and 24 months.

Measures of body fat distribution: defined using validated tools such as dual‐energy X‐ray absorptiometry (DXA), waist circumference, skin‐fold thickness, waist‐to‐hip ratio or bioelectrical impedance analysis and measured at baseline, and at least at 6, 12 and 24 months.

Behaviour change: defined as validated measures of diet and physical activity and measured at baseline, and at least at 6, 12 and 24 months.

Participants' views of the intervention: defined as documents accounts from participant feedback and measured at baseline, and at least at 6, 12 and 24 months.

Parent‐child relationship or assessment of parenting: evaluated by a validated instrument and measured at baseline, and at least at 6, 12 and 24 months.

Socioeconomic effects defined as a validated measure of socioeconomic status such as parental income or educational status and measured at baseline, and at least at 6, 12 and 24 months.

Summary of findings

We present a 'Summary of findings' table to report the following outcomes, listed according to priority.

Changes in BMI and body weight.

Adverse events.

Health‐related quality of life

All‐cause mortality.

Mobidity.

Parent‐dhild relationship or assessment of parenting.

Socioeconomic effects.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following sources from inception of each database to the specified date and placed no restrictions on the language of publication.

-

Cochrane Library:

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) (Issue 3, 10 March 2015).

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (Issue 3, 10 March 2015).

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (Issue 1, 10 March 2015).

Health Technology Assessment (HTA) (Issue 1, 10 March 2015).

MEDLINE and MEDLINE In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, 1946 to 10 March 2015.

EMBASE, 1974 to 10 March 2015.

PsycINFO, 1806 to 10 March 2015.

CINAHL (10 March 2015).

LILACS (10 March 2015).

ClinicalTrials.gov (10 March 2015).

-

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) Search Portal (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/), which is a meta‐register of trials with links to several trial registers, that includes

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (2 March 2015).

Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (2 March 2015).

ClinicalTrials.gov (2 March 2015).

EU Clinical Trials Register (EU‐CTR) (2 March 2015).

ISRCTN (International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number) Register (2 March 2015).

The Netherlands National Trial Register (2 March 2015).

Brazilian Clinical Trials Registry (2 February 2015).

Clinical Trials Registry ‐ India (2 March 2015).

Clinical Research Information Service ‐ Republic of Korea (3 March 2015).

Cuban Public Registry of Clinical Trials (3 March 2015).

German Clinical Trials Register (3 March 2015).

Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (3 March 2015).

Japan Primary Registries Network (3 March 2015).

Pan African Clinical Trial Registry (3 March 2015).

Sri Lanka Clinical Trials Registry (2 March 2015).

Thai Clinical Trials Register (3 March 2015).

We continuously applied a MEDLINE (via Ovid) email alert service established by the Cochrane Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders (CMED) Group to identify newly published trials using the same search strategy as described for MEDLINE (for details on search strategies see Appendix 1). Should we have identified new trials for inclusion, we would have evaluated these, incorporated findings in our review and re‐submitted another review draft (Beller 2013).

Searching other resources

We tried to identify other potentially eligible trials or ancillary publications by searching the reference lists of retrieved included trials, (systematic) reviews, meta‐analyses and HTA reports.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (two of RJ, LA, KR, EL, JC, WR, EM) independently scanned the abstract, title, or both, of every record retrieved, to determine which trials should be assessed further. We investigated all potentially relevant articles as full text. We resolved any discrepancies through consensus or recourse to a third review author (KR, EL, LA). Where resolution of a disagreement was not possible, we added the article to those 'awaiting assessment' and contacted study authors for clarification. We presented an adapted PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses) flow diagram showing the process of study selection (Liberati 2009).

Data extraction and management

For trials that fulfilled inclusion criteria, two review authors (two of RJ, LA, EL, JC, WR) independently abstracted key participant and intervention characteristics and reported data on efficacy outcomes and adverse events using standard data extraction templates as supplied by the CMED group, with any disagreements resolved by discussion, or, if required, by consultation with a third review author (KR) (for details see Table 5; Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4; Appendix 5; Appendix 6; Appendix 7; Appendix 8; Appendix 9).

1. Overview of study populations.

| Intervention(s) and comparator(s) | Sample sizea | Screened/eligible [N] | Randomised [N] | ITT [N] | Analysed [N] | Finishing trial [N] | Randomised finishing trial [%] | Follow‐up (extended follow‐up)a | |

| (20) Resnicow 2015 | I1: parent‐only PCP motivational interviewing | The study was powered to detect a 3‐point difference in BMI percentile between any pair of study groups at 2‐year follow‐up, with an assumed SD for BMI percentile between 4 and 6: power of 0.80 and 2‐tailed a of 0.05. Sample size was inflated to account for practice‐level clustering, assuming an intraclass correlation between 0.01 and 0.05. On this basis and a projected 25‐30% attrition at 2‐year follow‐up, 10‐12 practices per arm (30‐36 total) and a mean of 15‐20 children per practice at baseline were required | ‐ | 16 practices 212 participants |

145 | 145 | 145 | 68 | 2 years (2 years) |

| I2: parent‐only PCP + dietician motivational interviewing | 15 practices 235 participants |

154 | 154 | 154 | 66 | ||||

| C: usual care | 11 practices 198 participants |

158 | 158 | 158 | 80 | ||||

| total: | 645 | 457 | 457 | 457 | 71 | ||||

| (19) Mazzeo 2014 | I: parent NOURISH | ‐ | 235 | 48 | ‐ | 46 | 10 | 21 | 12 weeks post 12‐week intervention (24 weeks) |

| C: parent control | 45 | ‐ | 45 | 16 | 36 | ||||

| total: | 93 | 91 | 26 | 28 | |||||

| (18) Van Grieken 2013 | I: parent‐only | Sample size was calculated taking into account the intracluster correlation coefficient (ρ = 0.1), the number of clusters (44), the expected prevalence of overweight children in the study population, the SD, expected effect (a difference in mean), and the power of the study (80%). With a participation of 50%, an expected prevalence of overweight children of 9% and a loss‐to‐follow‐up of 30%, at least 11,301 children (and their parents) should be invited by the YHC teams to participate in the study to have a final sample of about 356 overweight children (178 in both the intervention and control group). Assuming a SD of BMI to be 1.0 kg/m2, a difference in mean BMI of 0.35 kg/m2 between the children in the intervention group and the children in the control group can be established under the assumptions mentioned above | 22 clusters 7004 participants |

349 | ‐ | 21 clusters 277 participants |

277 | 79 | 2 years post up to 12‐month intervention |

| C: usual care | 22 clusters 7004 participants |

288 | ‐ | 21 clusters 230 participants |

230 | 80 | |||

| total | 637 | ‐ | 42 (507) | 507 | 80 | ||||

| (17) Small 2013 | I: parent‐only | ‐ | ‐ | 34 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 97 | 24 weeks post 16‐week intervention (41 weeks) |

| C: parent control | 33 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 82 | ||||

| total: | 67 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 90 | ||||

| (16) Esfarjani 2013 | I: parent‐only | ‐ | 550/156 | 70 | ‐ | 55 | 58 | 83 | Intervention 6 months (not reported) |

| C: parent control | 86 | ‐ | 52 | 59 | 69 | ||||

| total: | 156 | ‐ | 107 | 117 | 75 | ||||

| (15) Moens 2012 | I: parent‐only | ‐ | 80/75 | 31 | ‐ | ‐ | 31 | 100 | Immediately following 6‐month intervention |

| C: waiting list control | 19 | ‐ | ‐ | 15 | 79 | ||||

| total: | 50 | ‐ | ‐ | 46 | 92 | ||||

| (14) Raynor 2012a | I1: parent‐only | Sample size calculations presumed 2‐sided hypothesis testing at 6‐month assessment, with type 1 error rate = 0.05. To reject with 80% power the null hypothesis of no pre‐ to post‐treatment difference between intervention conditions vs. the alternative that the pre‐ to post‐treatment difference was 0.6 or greater (effect size), 24 participants per group were needed | 549 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 29 | 88 | 24 weeks post 24‐week intervention (reported as '12 months') |

| I2: parent ‐ diet decrease | 33 | 33 | 33 | 29 | 88 | ||||

| I3: parent ‐ diet increase | 35 | 35 | 35 | 32 | 91 | ||||

| total: | 101 | 101 | 101 | 90 | 89 | ||||

| (13) Raynor 2012b | I1: parent‐only | Sample size calculations presumed 2‐sided hypothesis testing at 6‐month assessment, with type 1 error rate = 0.05. To reject with 80% power the null hypothesis of no pre‐ to post‐treatment difference between intervention conditions vs. the alternative that the pre‐ to post‐treatment difference is 0.6 or greater (effect size), 24 participants per group were needed | 549 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 26 | 90 | 24 weeks post 24‐week intervention (reported as '12 months') |

| I2: parent ‐ diet and activity traditional | 26 | 26 | 26 | 24 | 92 | ||||

| I3: parent ‐ diet and activity substitute | 26 | 26 | 26 | 24 | 92 | ||||

| total: | 81 | 81 | 81 | 74 | 91 | ||||

| (12) Margarey 2011 | I: parent healthy lifestyle | Sample size calculation was based on a reduction in BMI z score of 0.26 (SD 0.49) over 12 months (power 80%, alpha = 0.05, and drop‐out rate of 30%). This represents a 50% reduction in weight velocity over 12 months and no change in height velocity. We sought 42 children per group per site (168 children) | 398 | 85 | 85 | 85 | 52 | 61 | 80 weeks post 24‐week intervention (104 weeks) |

| C: healthy lifestyle | 84 | 84 | 84 | 54 | 64 | ||||

| total: | 169 | 169 | 169 | 106 | 63 | ||||

| (11) Jansen 2011 | I: parent CBT | ‐ | 161 | 59 | ‐ | 54 | 54 | 92 | 12 weeks post 12‐week intervention (24 weeks) |

| C: waiting list control | 39 | ‐ | 34 | 34 | 87 | ||||

| total: | 98 | 88 | 88 | 90 | |||||

| (10) Collins 2011 | I: parent‐only ‐ diet | Power: 80% chance of detecting significance (2‐sided 5% level), with a 0.26 BMI z score difference from baseline to 12 months as the initial end point, with an anticipated loss to follow‐up of 20% | 505/319 | 63 | ‐ | 42 | 22 | 35 | 80 weeks post 24‐week intervention (104 weeks) |

| C1: parent‐child (physical activity) | 73 | ‐ | 63 | 35 | 48 | ||||

| C2: parent‐child (physical activity + diet) | 70 | ‐ | 60 | 36 | 51 | ||||

| total: | 206 | ‐ | 165 | 93 | 45 | ||||

| (9) Boutelle 2011 | I: parent‐only | Sample size was determined by pragmatic factors, including budget and investigator time commitments. No interim analyses were done. The hypotheses tested related to non‐inferiority of the parent treatment to the parent‐child treatment on child and parent weight loss and child daily caloric intake and physical activity. The bound for non‐inferiority hypotheses related to BMI percentile was set to 1. This is the maximum value the parent‐child group could do better than parent‐only, below which non‐inferiority would be concluded. This bound could correspond to an mean‐aged child in this sample having a BMI of 26 in the parent‐child group and 28.5 in the parent‐only group at post‐treatment/follow‐up, assuming equivalence at baseline. For a non‐inferiority bound for child BMI, which was selected post hoc, we considered choosing a BMI that would correspond to the BMI percentile non‐inferiority bound (BMI = 2.5), but instead chose a more rigorous value of BMI = 1 | 157 | 40 | ‐ | 24 | 24 | 60 | 24 weeks post 20‐week intervention (week 44) |

| C: parent‐child | 40 | ‐ | 28 | 28 | 70 | ||||

| total: | 80 | 52 | 52 | 65 | |||||

| (8) West 2010 | I: parent‐only | ‐ | 205 | 52 | 52 | 52 | 34 | 65 | 40 weeks post 12‐week intervention (52 weeks) |

| C: waiting list control | 49 | 49 | 49 | 46 | 94 | ||||

| total: | 101 | 101 | 101 | 80 | 79 | ||||

| (7) Resnick 2009 | I: educational material + personal encounters | ‐ | 84/46 | 22 | ‐ | 18 | 18 | 82 | Unclear (41 weeks between start and last mail out) |

| C: educational material | 24 | ‐ | 24 | 24 | 100 | ||||

| total: | 46 | 42 | 42 | 91 | |||||

| (6) Estabrooks 2009 | I1: parent group + IVR | Sample size calculations were completed, varying the detectable effect sizes from small to medium with a power of 0.8. The result was a need for 42 participants per intervention to detect a medium effect and 64 participants to detect a small effect | 1487/656 | 85 | ‐ | 63 | 63 | 74 | 28‐40 weeks post 12‐ to 24‐week intervention (52 weeks) |

| I2: parent group | 85 | ‐ | 56 | 56 | 66 | ||||

| C: parent workbook | 50 | ‐ | 36 | 36 | 72 | ||||

| total: | 220 | 155 | 155 | 70 | |||||

| (5) Munsch 2008 | I: mother‐only CBT | Trial authors did not reach the necessary sample size of 68 families with obese children within the given time span (the target sample size of 68 was based on a repeated‐measures analysis with alpha = 0.05, 1 ‐ beta = 0.8, and a medium effect size for the linear term of the interaction between treatment and time, assuming a drop‐out rate of 20% | 181/60 | 25 | ‐ | 7 | 7 | 28 | 24 weeks post 10‐week intervention (34 weeks) |

| C: mother‐child CBT | 31 | ‐ | 20 | 20 | 65 | ||||

| total: | 56 | 27 | 27 | 48 | |||||

| (4) Janicke 2008 | I: parent‐only | Post hoc power analyses were used to determine the detectable change in BMI z score from 0 to 10 months for the family based and parent‐only interventions relative to the waiting list control condition. Effect sizes (standardised BMI index) detectable with 80% power and 2‐sided level 0.05 tests were used. Standard deviations and sample sizes were set equal to their observed values. For comparing the family‐based and waiting list control conditions, trial authors reported 80% power to detect a shift from 0.022 to ‐0.145. For comparing the parent‐only and waiting list control conditions, trial authors reported 80% power to detect a shift from 0.022 to ‐0.135 | 111 | 34 | ‐ | 26 | 26 | 76 | 14 weeks post 16‐week intervention (40 weeks) |

| C1: parent‐child | 33 | ‐ | 24 | 24 | 73 | ||||

| C2: waiting list control | 26 | ‐ | 21 | 21 | 81 | ||||

| total: | 93 | 71 | 71 | 76 | |||||

| (3) Golley 2007 | I: parent intervention + lifestyle education | Sample size calculation was based on a fall in BMI z score reflecting a weight gain of only 50% of that expected over 12 months with normal growth. A sample size of 28 per group was estimated to have 80% power to detect a 12‐month fall in mean BMI z score from a baseline of 0.26 (SD 0.49), assuming no change in the control group, at a 2‐sided significance level of 0.05. To account for a drop‐out rate of up to one‐third (commonly 20‐50% in child weight‐management studies), 42 children per study group were sought (126 children) | 262/115 | 38 | ‐ | 31 | 31 | 82 | 24 weeks post 24‐week intervention (48 weeks) |

| C1: parent intervention | 37 | ‐ | 29 | 29 | 78 | ||||

| C2: waiting list control | 36 | ‐ | 31 | 31 | 86 | ||||

| total: | 111 | 101 | 101 | ‐ | |||||

| (2) Golan 2006 | I: parent‐only | The study was designed to detect differences of 10% weight loss with a power of 90% and a significance level of 0.05, given a drop‐out rate of 10% with a sample of 12 in each group | 102 | 14 | ‐ | 10 | 10 | 71 | 1 year post 26‐week intervention (18 months) |

| C: parent‐child | 18 | ‐ | 17 | 17 | 94 | ||||

| total: | 32 | 27 | 27 | 84 | |||||

| (1) Aragona 1975 | I1: parent‐only with reinforcement | ‐ | ‐ | 5 | ‐ | 4 | 4 | 80 | 12 weeks (51 weeks' follow‐up) |

| I2: parent‐only | 5 | ‐ | 3 | 3 | 60 | ||||

| C: waiting list control | 5 | ‐ | 5 | 2 | 40 | ||||

| total: | 15 | 12 | 9 | 60 | |||||

| Grand total | All interventions | ‐ | 1773c | 1276 | |||||

| All comparators | 1284c | 942 | |||||||

| All interventions and comparators | 3057c | 2218 | |||||||

aAccording to power calculation in trial publication or report bDuration of intervention or follow‐up (or both) under randomised conditions until end of trial cSome trials had more than one intervention/comparator group

"‐" denotes not reported

BMI: body mass index; C: comparator; CBT: cognitive behavioural therapy; I: intervention; ITT: intention‐to‐treat; IVR: interactive voice response; n: number of participants; NOURISH: nourishing our understanding of role modelling to improve support and health; PCP: primary care providers; SD: standard deviation; YHC: Youth Health Care

We provided information including trial identifier about potentially relevant ongoing trials in the Characteristics of ongoing studies table and in the 'Matrix of study endpoints (publications and trial documents)' where available. We tried to find the protocol of each included study in trial registers or publications of study designs, or both, and reported primary, secondary and other outcomes in comparison with data in publications in Appendix 5.

We emailed all authors of included trials to enquire whether they were willing to answer questions regarding their trials. Appendix 10 shows the results of this survey. Thereafter, we sought relevant missing information on the trial from the primary author(s) of the article, if required.

Dealing with duplicate and companion publications

In the event of duplicate publications, companion documents or multiple reports of a primary study, we tried to maximise yield of information by collating all available data and use the most complete data set aggregated across all known publications. In case of doubt, we gave priority to the publication reporting the longest follow‐up associated with our primary or secondary outcomes.

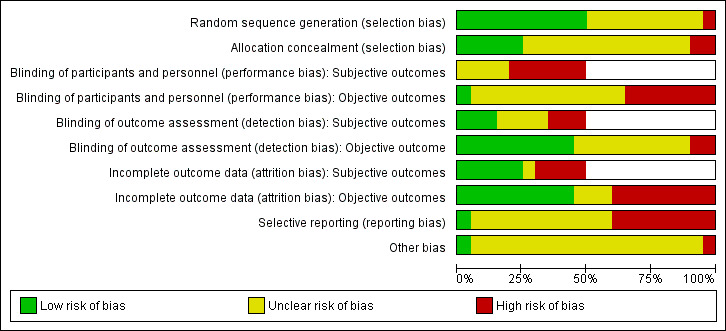

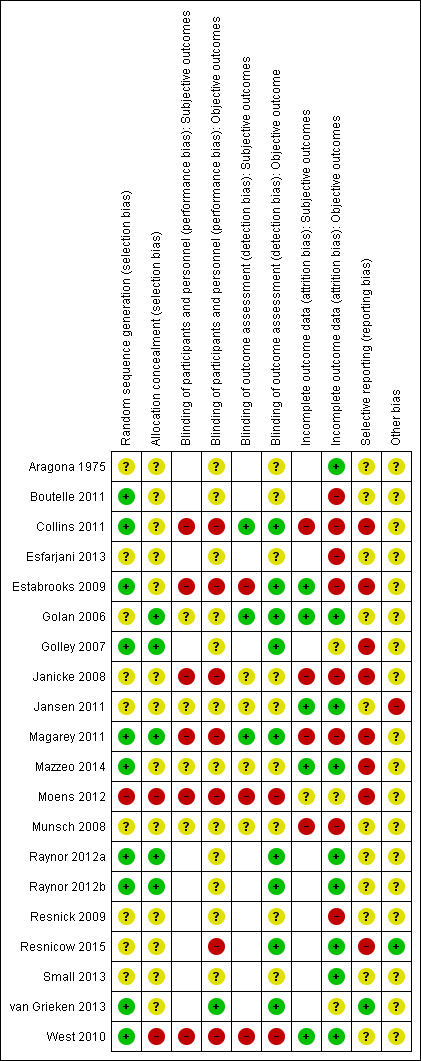

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (two of RJ, LA, EL, JC) assessed the risk of bias of each included study independently. We resolved possible disagreements by consensus, or with consultation with a third review author (KR).

We used Cochrane's tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011a; Higgins 2011b), and evaluated the following criteria.

Random sequence generation (selection bias).

Allocation concealment (selection bias).

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias).

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias).

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).

Selective reporting (reporting bias).

Other potential sources of bias.

We judged the above risk of bias criteria as 'low risk', 'high risk' or 'unclear risk' and evaluated individual bias items as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). We presented a 'Risk of bias' graph and a 'Risk of bias' summary. We assessed the impact of individual bias domains on study results at endpoint and study levels. In case of high risk of selection bias, we marked all endpoints investigated in the associated study as high risk.

We evaluated whether imbalances in baseline characteristics existed and how these were addressed (Egbewale 2014).

For performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel) and detection bias (blinding of outcome assessors), we evaluated the risk of bias separately for each outcome type (objective and subjective) (Hróbjartsson 2013).

We considered the implications of missing outcome data from individual participants per outcome such as high drop‐out rates (e.g. above 15%) or disparate attrition rates (e.g. difference of 10% or more between study arms).

We assessed outcome reporting bias by integrating the results of 'Examination of outcome reporting bias' (Appendix 6) and the 'Matrix of study endpoints (publications and trial documents)' (Appendix 5) (Kirkham 2010). This analysis formed the basis for the judgement of selective reporting (reporting bias).

We defined the following as self reported outcomes ('subjective outcomes').

Adverse events.

Health‐related quality of life and self esteem.

Parent‐child relationship or assessment of parenting.

Participants' views of the intervention.

We defined the following as investigator‐assessed outcomes ('objective outcomes').

Changes in BMI measures and body weight.

Measures of body fat distribution.

Adverse events.

All‐cause mortality.

Morbidity.

Behaviour change.

Socioeconomic effects.

Measures of treatment effect

We expressed dichotomous data as odds ratios (ORs) or risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We expressed continuous data as mean differences (MD) with 95% CI. We planned to express time‐to‐event data as hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CIs.

Unit of analysis issues

We took into account the level at which randomisation occurred, such as cross‐over trials, cluster‐randomised trials and multiple observations for the same outcome. For cluster‐randomised trials, we used the adjusted data reported in the original studies. Where studies had multiple control groups, we used data from the control group for each comparison by reducing the weight assigned to the control group by dividing the number of participants in the control group by the number of intervention groups.

Dealing with missing data

We obtained relevant missing data from authors, if possible, and evaluated important numerical data such as screened, eligible, randomised participants as well as intention‐to‐treat (ITT), as‐treated and per‐protocol (PP) populations where possible. We investigated attrition rates, for example drop‐outs, losses to follow‐up and withdrawals, and critically appraise issues of missing data and imputation methods (e.g. last‐observation‐carried‐forward (LOCF)).

Where standard deviations (SD) for outcomes were not reported, and we did not receive information from study authors, we calculated these following the methods presented in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). Where papers did not report results as change from baseline, we calculated this and for the SD differences followed the methods presented in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions for imputing these (Section 16.1.3.2 Imputing standard deviations for changes from baseline; Higgins 2011a), and assumed a correlation of 0.5 between baseline and follow‐up measures as suggested by Follman 1992.

Assessment of heterogeneity

In the event of substantial clinical or methodological heterogeneity, we did not report study results as meta‐analytically pooled effect estimates. We identified heterogeneity by visual inspection of the forest plots and by using a standard Chi2 test with a significance level of α = 0.1, in view of the low power of this test. We examined heterogeneity using the I2 statistic, which quantifies inconsistency across trials to assess the impact of heterogeneity on the meta‐analysis (Higgins 2002; Higgins 2003), where an I2 statistic of 75% or more indicates a considerable level of inconsistency (Higgins 2011a).

When we found heterogeneity, we attempted to determine potential reasons for it by examining individual study and subgroup characteristics.

Assessment of reporting biases

If we had included 10 trials or more for a given outcome, we would have used funnel plots to assess small‐study effects. Due to several explanations for funnel plot asymmetry, we would have interpreted results carefully (Sterne 2011).

Data synthesis

Unless there was good evidence for homogeneous effects across trials, we primarily summarised data by means of a random‐effects model (Wood 2008). We had planned to interpret random‐effects meta‐analyses with due consideration of the whole distribution of effects, ideally by presenting a prediction interval; however, there were relatively few trials included in each category, of low methodological quality and so theses analyses were not conducted (Higgins 2009). A prediction interval specifies a predicted range for the true treatment effect in an individual study (Riley 2011). We performed statistical analyses according to the statistical guidelines referenced in the latest version of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a).

Quality of evidence

We present the overall quality of the evidence for each outcome according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach, which takes into account issues not only related to internal validity (risk of bias, inconsistency, imprecision, publication bias) but also to external validity such as directness of results. Two review authors (EL, KR) rated the quality for each outcome. We presented a summaries of the evidence in a 'Summary of findings' tables, which provide key information about the best estimate of the magnitude of the effect, in relative terms and absolute differences for each relevant comparison of alternative management strategies, numbers of participants and trials addressing each important outcome, and the rating of the overall confidence in effect estimates for each outcome. We created the 'Summary of findings' tables based on the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). We presented results on the outcomes as described in Types of outcome measures.

In addition, we established an appendix 'Checklist to aid consistency and reproducibility of GRADE assessments' (Meader 2014) to help with standardisation of 'Summary of findings' tables (Appendix 9).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We expected the following characteristics to introduce clinical heterogeneity, and aimed to carry out subgroup analyses with investigation of interactions where data permitted.

Differences in BMI at baseline.

Length of follow‐up.

The impact of comparator/control: whether concomitant therapy or no treatment (true control).

The setting in which the intervention was conducted.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform sensitivity analyses to explore the influence of the following factors on effect size.

Restricting the analysis to published trials.

Restricting the analysis taking into account risk of bias, as specified in the 'Assessment of risk of bias in included studies' section.

Restricting the analysis to very long or large trials to establish how much they dominated the results.

Restricting the analysis to trials using the following filters: diagnostic criteria, language of publication, source of funding (industry versus other), country.

We tested the robustness of the results by repeating the analysis using different statistical models (fixed‐effect and random‐effects models).

Results

Description of studies

For a detailed description of trials, see the Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies and Characteristics of ongoing studies tables.

Results of the search

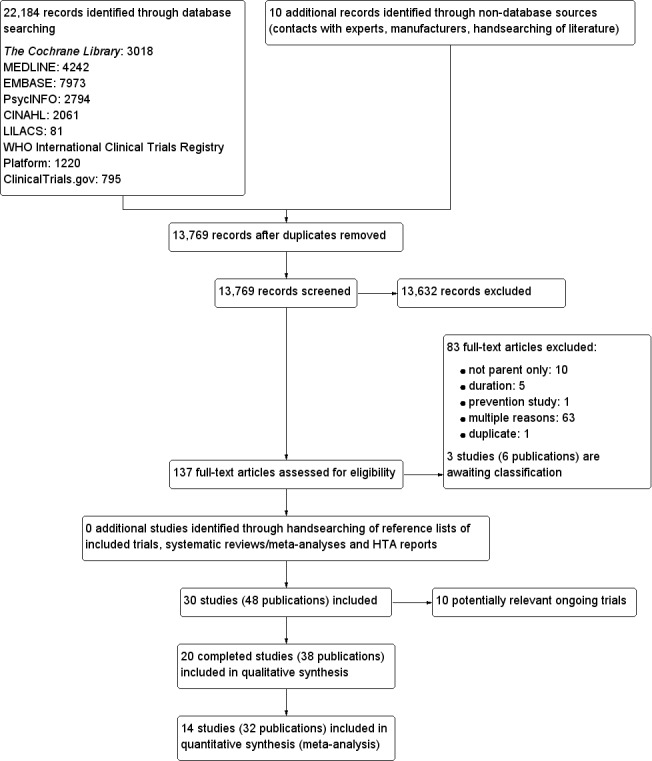

The searches generated 13,759 hits after duplicates were removed. Screening of titles and abstracts identified 137 papers to go forward for formal inclusion and exclusion. Twenty completed RCTs fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in the review. For a detailed description of the included trials, see the Characteristics of included studies table. The search identified 10 ongoing trials, which are reported in the Characteristics of ongoing studies table. The flow of trials through the review is presented in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

A detailed description of the characteristics of included trials is presented elsewhere (see Characteristics of included studies table and Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4; Appendix 5; Appendix 6; Appendix 7; Appendix 8; Appendix 9). The following is a succinct overview.

Source of data

The majority of data presented in the review was obtained from published literature, including supplementary published data where available. For five trials, trial authors provided data (Appendix 10).

Study details

We included 20 RCTs in 19 main publications (Aragona 1975; Boutelle 2011; Collins 2011; Esfarjani 2013; Estabrooks 2009; Golan 2006; Golley 2007; Janicke 2008; Jansen 2011; Magarey 2011; Mazzeo 2014; Munsch 2008; Raynor 2012a; Raynor 2012b; Resnick 2009; Resnicow 2015; Small 2013; van Grieken 2013; West 2010). Eighteen RCTs were parallel comparisons with individual randomisation. In most trials, the unit of randomisation was the family (parent and child); however, study authors analysed the children and parents for respective outcomes separately. Two RCTs were cluster RCTs, where the Primary Care Provider (PCP) (Resnicow 2015) or Youth Health Care (YHC) (van Grieken 2013) team were the unit of randomisation. Eighteen RCTs were superiority trials, one had a non‐inferiority study design (Boutelle 2011), and one an equivalence study design (Munsch 2008). Eight RCTs had three comparisons (Aragona 1975; Collins 2011; Estabrooks 2009; Golley 2007; Janicke 2008; Raynor 2012a; Raynor 2012b; Resnicow 2015); the remaining trials had two comparison groups.

Ten trials were undertaken in the USA (Aragona 1975; Boutelle 2011; Estabrooks 2009; Janicke 2008; Mazzeo 2014; Raynor 2012a; Raynor 2012b; Resnick 2009; Resnicow 2015; Small 2013); four in Australia (Collins 2011; Golley 2007; Magarey 2011; West 2010), and two in the Netherlands (Jansen 2011; van Grieken 2013). There was one trial each from Israel (Golan 2006), Switzerland (Munsch 2008), Iran (Esfarjani 2013), and Belgium (Moens 2012). Five trials were single‐centre trials (Aragona 1975; Boutelle 2011; Esfarjani 2013; Golan 2006; Moens 2012); the remaining trials were either multi‐centre trials (with two centres: Golley 2007; Munsch 2008; Resnick 2009; three centres: Jansen 2011; Magarey 2011; and six centres: West 2010), or the numbers of centres were not reported (Collins 2011; Estabrooks 2009; Janicke 2008; Mazzeo 2014; Raynor 2012a; Raynor 2012b; Small 2013). The cluster RCT by van Grieken 2013 was undertaken in nine study centres, across 44 healthcare teams. The cluster RCT by Resnicow 2015 was undertaken in 42 primary care practices.

Overview of study populations

All trials included parents of overweight or obese children. The diagnostic criteria differed between trials, in 10 trials this was based on the BMI 85th percentile (Boutelle 2011; Estabrooks 2009; Golan 2006; Janicke 2008; Mazzeo 2014; Munsch 2008; Raynor 2012a; Raynor 2012b; Resnick 2009; Resnicow 2015), and in one trial the BMI 95th percentile (Esfarjani 2013). In other trials, this was based on the parent or physician describing their child as overweight (Aragona 1975; Moens 2012; Small 2013; West 2010); the IOTF definition (Golley 2007; Magarey 2011), or stated as international cut‐off points that were not specified (van Grieken 2013); a specified BMI cut‐off (Collins 2011); or the proportion of BMI above expected BMI (at least 30% greater in Jansen 2011).

All trials included parents of children aged between 4 and 13 years, the majority of which did not include children above 11 years of age. The mean ages of participants were reported in 16 trials. In six trials, the mean ages were between 5 and 7 years (Esfarjani 2013; Raynor 2012a; Raynor 2012b; Resnicow 2015; Small 2013; van Grieken 2013); in seven trials, the mean ages were between 8 and 9 years (Aragona 1975; Collins 2011; Golan 2006; Magarey 2011; Moens 2012; West 2010); and in four trials, the mean ages of the children was between 10 and 11 years (Boutelle 2011; Estabrooks 2009; Janicke 2008; Munsch 2008). The proportion of girls in the trials typically ranged from 40% to 70% where reported (four trials did not report this: Esfarjani 2013; Janicke 2008; Mazzeo 2014; Resnick 2009), although was 100% in one study (Aragona 1975). Only eight trials reported ethnicity of the children and in all trials there was a high proportion of children categorised as white (between 60% and 100% across all trials: Estabrooks 2009; Janicke 2008; Moens 2012; Raynor 2012a; Raynor 2012b; Resnicow 2015; Small 2013; West 2010). Only eight trials reported socioeconomic indices of the parents (Boutelle 2011; Esfarjani 2013; Janicke 2008; Moens 2012; Resnicow 2015; Small 2013; van Grieken 2013; West 2010). Each used a different indicator of socioeconomic status (see Appendix 4).

The number of participants included in the 19 trials ranged between 15 and 645. Five trials had fewer than 30 participants per study arm (Aragona 1975; Moens 2012; Munsch 2008; Raynor 2012b; Resnick 2009), whereas four trials had greater than 60 participants per study arm (Collins 2011; Esfarjani 2013; Estabrooks 2009; Magarey 2011). In the cluster RCT by van Grieken 2013, there were 22 clusters in each arm (total 637 participants), in the Resnicow 2015 cluster RCT, there were 42 clusters (total 645 participants).

Seven trials reported the BMI z score, which ranged from 2.0 to 2.8 at baseline (Boutelle 2011; Collins 2011; Estabrooks 2009; Golley 2007; Janicke 2008; Magarey 2011; West 2010). Five trials reported the BMI percentile, which ranged from 92% to 98.5% at baseline (Jansen 2011; Mazzeo 2014; Resnick 2009; Resnicow 2015; Small 2013). Five trials reported BMI (Esfarjani 2013; Mazzeo 2014; Munsch 2008; Raynor 2012a; Raynor 2012b), and could be calculated from individual participant data in one other study (Aragona 1975). The BMI in these trials ranged from 22 to 33.6 at baseline. Eleven trials reported parental BMI. In eight trials, the mean parental BMI ranged between 26 and 36; with four trials including parents with BMIs between 26 and 30 (Jansen 2011; Munsch 2008; Resnick 2009; Resnicow 2015), and four trials including parents with BMIs above 30 (Boutelle 2011; Janicke 2008; Mazzeo 2014; Small 2013). One study reported the proportions of parents in three categories (healthy, overweight, obese); these were approximately 37% (healthy), 23% (overweight) and 40% (obese) (West 2010). Another study reported the proportions of 'normal' (about 56%) and 'overweight' (about 44%) (van Grieken 2013). One study reported the weight of the parents (for mothers and fathers for each group respectively) (Golan 2006).

For details of baseline characteristics of participants in the included trials, see Appendix 4 and Appendix 5. There were no substantial differences in baseline characteristics between the intervention and comparator groups in the included trials.

Interventions

Seventeen trials reported the settings for the interventions. In four trials, the intervention was in an outpatient setting (Collins 2011; Estabrooks 2009; Golley 2007; Magarey 2011), and in four trials it was a community setting (Janicke 2008; Mazzeo 2014; Resnick 2009; van Grieken 2013). Two trials were undertaken in a university setting (Boutelle 2011; Moens 2012); two in a primary care setting (Resnicow 2015; Small 2013), and five trials win a mixture of settings including outpatient, university, primary care or a combination of these settings (Jansen 2011; Munsch 2008; Raynor 2012a; Raynor 2012b; West 2010).

The interventions in the included trials predominantly focused on nutritional, physical activity and behavioural components; see Characteristics of included studies table and Appendix 2 for specific details for each included study.

Five trials compared a parent‐only intervention to a parent‐child intervention (two also had a third comparison of a waiting list control, Janicke 2008 or a second parent‐child intervention, Collins 2011) (Boutelle 2011; Collins 2011; Golan 2006; Janicke 2008; Munsch 2008). In one study, the duration of the intervention was 10 weeks (Munsch 2008); and four trials had interventions of 16 to 24 weeks' duration (Boutelle 2011; Collins 2011; Golan 2006; Janicke 2008). Session lengths ranged from one to two hours in all five trials. All trials followed participants beyond the timing of the end of the intervention. This was 14 weeks' post intervention in one study (Janicke 2008), 24 to 26 weeks' post intervention in two trials (Boutelle 2011; Munsch 2008), one year post intervention in one trial (Golan 2006), and 80 weeks' post intervention in one study (Collins 2011).

Six trials compared a parent‐only intervention to a waiting list control (Aragona 1975; Golley 2007; Janicke 2008; Jansen 2011; Moens 2012; West 2010) and two of these trials had two different parent‐only interventions (Aragona 1975; Golley 2007). The duration of the intervention ranged from 12 to 24 weeks in these trials and sessions ranged between 90 minutes and two hours (one study did not provide details, Aragona 1975). In two trials, there were additional sessions via telephone contact between interventionists and the parents, which were approximately 20 minutes long (Golley 2007; West 2010). All but one study followed participants up beyond the timing of the end of the intervention (Moens 2012). This was 12 to 14 weeks post intervention in one trial (Jansen 2011), 24 weeks post intervention in two trials (Golley 2007; Janicke 2008), 39 weeks post intervention in one trial (Aragona 1975) and 40 weeks post intervention in one trial West 2010).

Seven trials compared a parent‐only intervention with a minimal contact parenting advice control (mailed information or a workbook or minimal sessions) (Esfarjani 2013; Estabrooks 2009; Mazzeo 2014; Resnick 2009; Resnicow 2015; Small 2013; van Grieken 2013); two trials had two different parent‐only interventions (Estabrooks 2009; Resnicow 2015). The duration of the interventions ranged from 12 to 26 weeks in five trials (in the Resnick 2009 study the interventions ranged from 30 to 41 weeks but the study reports a mean of 18 weeks). In one study, the duration of the intervention differed for each participants, but was up to 12 months (van Grieken 2013). In one trial, the intervention continued to 24 months (Resnicow 2015). In three trials, the number of sessions provided to parents was lower than reported in the other parent‐only interventions, being three or four sessions (Resnick 2009; Small 2013; van Grieken 2013). In two trials, the intervention was delivered across 12 sessions (Esfarjani 2013; Mazzeo 2014); in the study by Estabrooks 2009, there were two parent‐only treatment arms, which were either 12 or 24 weeks in duration and in the study by Resnicow 2015, there were also two parent‐only treatment arms, which were either four or 10 sessions. Six trials reported the duration of follow‐up in relation to the completion of the intervention. In the study by Mazzeo 2014, this was 12 weeks post intervention completion, in Small 2013, this was 24 weeks post completion of the intervention, in Estabrooks 2009, this was between 28 and 40 weeks post completion of the intervention and in Aragona 1975, this was 39 weeks post completion of the intervention. In the van Grieken 2013 RCT, follow‐up was 24 months after baseline (the duration of the intervention was "up to 12 months") and in the Resnicow 2015 trial, follow‐up was at completion of the intervention at 24 months.

Seven trials compared different types of parent‐only interventions (Aragona 1975; Estabrooks 2009; Golley 2007; Magarey 2011; Raynor 2012a; Raynor 2012b; Resnicow 2015), two also had a parent‐only versus waiting list control comparison (Aragona 1975; Golley 2007), and two trials also had a parent‐only versus minimal contact intervention (Estabrooks 2009; Resnicow 2015). In the first, by Estabrooks 2009, there were three treatment arms. In one treatment group, the parents received a self help workbook, attended two group sessions and these were followed up with 10 interactive voice response (IVR) counselling sessions over a 10‐week period. In the second arm, the parents received the work book and attended the same two group sessions but did not have the IVR follow‐up sessions. In the third group, parents received the workbook only. In the study by Resnicow 2015, participants either received motivational interviewing over four sessions in the primary care practice, or received the four motivational interviewing sessions and six sessions with a dietician (the third arm received usual care information). In the study by Magarey 2011, parents were randomised into two arms, one received a four‐session parenting programme that was followed by eight group sessions about healthy lifestyles. The second group received the eight sessions about healthy lifestyles only. Both the trials by Estabrooks 2009 and Magarey 2011 followed participants up beyond the timing of the end of the intervention. In the study by Estabrooks 2009, this was between 28 and 40 weeks post completion of the intervention and in the study by Magarey 2011, this was 80 weeks post completion of the intervention. In the study by Resnicow 2015, follow‐up was at the point of completing the intervention (24 weeks) although in the second 12‐month period of the intervention there were fewer sessions held.

Two trials in one publication also compared different parent‐only interventions (Raynor 2012a; Raynor 2012b). There were many shared attributes of the two trials. The first trial compared a parent‐only intervention that focused on growth monitoring to a parent intervention that focused on decreasing sugary foods in the diet and a parent intervention that focused on increasing healthy food consumption (Raynor 2012a). Parents randomised to the two comparison groups also received the parent‐only intervention (growth monitoring). The second study compared the parent‐only intervention to a parent intervention that focused on decreasing sugary foods and increasing physical activity, and to a parent intervention that focused on increasing low‐fat milk intake and decreasing television watching (Raynor 2012b). Parents randomised to the two comparison groups also received the parent‐only 'growth monitoring' intervention. The duration of the interventions in these two trials was six months, and there were eight sessions of 45 minutes' duration. These trials followed participants up 24 weeks after the timing of the end of the intervention. Golley 2007 compared parenting skills training with the addition of intensive lifestyle education with the parenting skills training without the additional intensive lifestyle education. The duration of the interventions are as described above. Aragona 1975 compared a parenting response‐cost and training in reinforcement skills with the response‐cost training only. Parents were required to enter a contract with the interventionists and pay a deposit relating to a goal of weight loss in their child, which could be returned for attendance at the sessions and when the goal was achieved. The duration of the interventions is as described above.