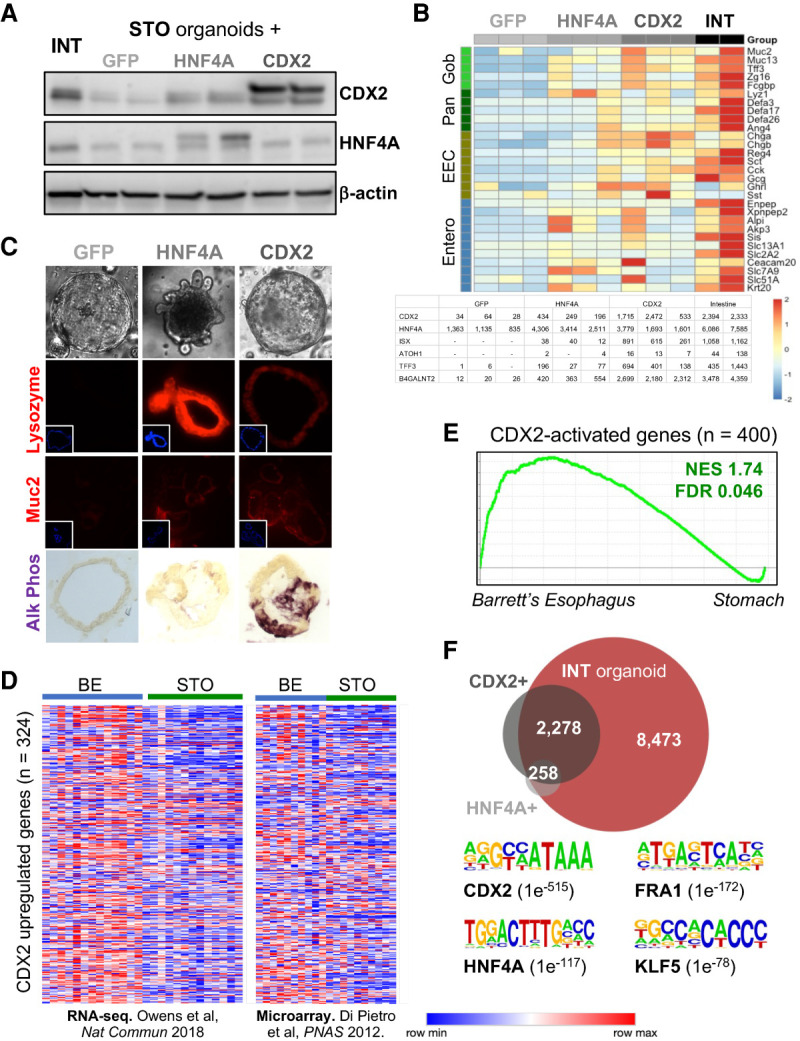

Figure 1.

Intestinal TFs induce an intestinal program in mouse stomach organoids. (A) Immunoblots of forced GFP (control), HNF4A, or CDX2 expression in gastric organoids. Each lane represents a distinct organoid line. (B) Expression of intestinal genes representing goblet, enterocyte, enteroendocrine, and Paneth cells in stomach organoids that express GFP, HNF4A, or CDX2, and in intestinal organoids (INT). A table of normalized RNA-seq counts from each organoid line shows CDX2 and HNF4A overexpression and up-regulation of canonical intestinal transcripts. (C, top) Bright-field microscopy of representative stomach organoids, including some with buds that resemble intestinal crypt-like outpouchings. (Bottom) Histochemistry (lysozyme and Muc2 immunostain and alkaline phosphatase) showing intestinal features. (D) Two independent human BE data sets (di Pietro et al. 2012; Owen et al. 2018) show that genes responsive to CDX2 in mouse stomach organoids are up-regulated in BE compared with native stomach epithelium. (E) Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of 400 genes induced in CDX2+ gastric organoids (log2 fold increase >1, q < 0.05, DESeq2), showing resemblance to human BE (data from clinical samples) (Owen et al. 2018). (NES) Normalized enrichment score, (FDR) false discovery rate. (F) Enhancers with increased chromatin access (log2 fold change >1, q < 0.05, DESeq2) in CDX2+ and HNF4A+ stomach organoids overlap significantly with sites selectively accessible in intestinal compared with stomach organoids. Representation factors 7344 (CDX2) and 7748 (HNF4A); P = 0. Motifs for intestinal TFs are highly enriched at enhancers rendered accessible in the presence of CDX2.