| Key structures |

The government very quickly scaled-up testing for COVID-19 within the public health system. Early studies alluded to the presymptomatic and asymptomatic spread.109 110 The test, trace and isolate system managed by the public health system which received major financial and personal support for its activities. Federal governments supported generation of evidence through funding, such as the assessment of infection-fatality rate after a superspreading event.105

|

|

Testing, originally planned to be managed by the public system, was suspended in March 2020, and only provided to those being admitted to hospitals due to capacity problems. Since April 2020, tracing and testing is done primarily by private firms. Some local authorities developed their own test and trace system in response to this.50 During the first wave local authorities had no access to data.111 Directors of Public Health started to receive postcode-level data on infections in their area only from 24 June 2020.

|

| Laboratory surveillance of identified infections |

|

|

|

| Deaths |

|

|

|

| Surveys of infection in the community |

RKI-SOEP study a longitudinal design including 30 000 people/15 000 households. Several smaller and larger studies, for example, the Kupferzell study is investigating one of the early hotspots. In addition, there are several studies independently from RKI on schools and preschools, etc.

|

|

COVID-19 Infection Survey (ONS), established in April 2020, repeated cross-sectional (once-a-month) population-based survey intervals.112 REACT, repeated cross-sectional survey (5+ years) in samples of 100 000 participants.113 114

|

| Messaging |

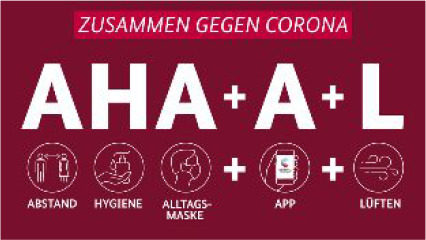

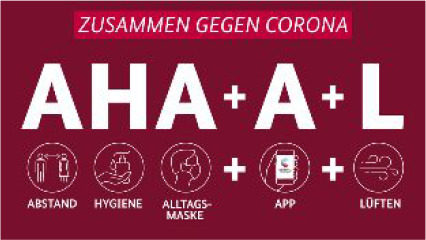

The key messages in the pandemic were not changed but complemented throughout the pandemic.

To support the national curfew in March and April, the slogan ‘We stay home’ was circulated since 18 March.115

First messages included distance and hygiene. Wearing a non-medical mask was added in May.

With the launch of the CoronaApp 16 June and the evolving evidence that the disease is transmitted by small droplets (aerosols) the logan was further expanded to encompass the opening of windows for air circulation.

Translation: A Abstand (distance), H Hygiene, A Alltagsmaske (non-medical masks)+A App (Corona-App)+L Lueften (air circulation). |

The main messages remained unchanged throughout 2020.

The key message of ‘stay home when you are sick’116 was complemented by ‘wash your hands and the rule of 2-metre distance’.

Asymptomatic/presymptomatic transmission was little recognised.117

Masks were recommended only in 2021 and only in limited settings such as health facilities. |

Messages and slogans changed throughout 2020, which was perceived as confusing by the population.71

-

Stay at home, protect the NHS, save lives (March 2020).

Stay alert, control the virus, save lives (May 2020). -

Hands, face, space—wash hands, cover face, make space (July 2020).

Rule of six (September 2020). ‘V-Day’ (December 2020).

|

| Communicating goals |

(i) Reducing morbidity and mortality in the population, (ii) caring for sick people, (iii) maintaining essential public services and (iv) providing reliable and timely information for political decision-makers, specialists, public and the media.118

|

(i) Protect senior and/or vulnerable citizens and (ii) slow down the spread of the virus so. The strategy was communicated as lowering the epidemic curve.53 119 It remains unclear (and debated) if reaching herd immunity was an underlying goal.61 Emails released under the public transparency law and public talks and written comments by Giesecke, a key advisor to the PHA, suggested that allowing the infection to spread slowly to establish immunity may have been an underlying philosophy.120 121

|

Pandemic action plan listed 3 phases—contain phase; the delay phase; the research phase and the mitigate phase—phased response.122 This plan has not been updated. Specific plans have complemented this initial plan including, for example, the UK COVID-19 vaccines delivery plan and the Test and Trace Business Plan.

|

| Communicating goals and data |

R0 below 1 as well as a cut-off value of 50 infections in a week per 100 000 population. The RKI informed the public throughout the epidemic on the homepage (German and English), regular (typically biweekly) press-conferences on figures of infection, transmission and deaths. Sex and age distribution. Regular reporting on infections in home for elderly and in educational institutions.

|

No clear goal or target formulated. Daily press conferences, with a focus on mortality data (testing particular at the beginning at the pandemic restricted to severely ill patients for diagnostic in hospitals). Sex and age distribution, at times also subgroups.

|

No clear goal or target formulated, instead phases are defined and an overall goal of protecting the NHS. The 3-tier, and since December 2020, the 4-tier approach clearly outlines what can be done and what is not allowed if a region or a town which goes into a certain tier. From 3 March daily press conferences aimed at explaining the government response to the COVID-19 outbreak which was interrupted on 23 June 2020 and resumed to some extent after 20 October 2020. Press conference involve the prime minister or a minister, the CMO or CSA, and most of the time an NHS representative.

|

| Communication of uncertainty |

Government included a strong narrative of uncertainty throughout the communication. The Minister of Health, Jens Spahn in a speech in the German parliament on 22 April summarised that there was a very steep joint learning curve, and that in view of all the uncertainty around the COVID-19 pandemic he foresees that we will need to apologise each other for wrong decisions.123

|

Communication of uncertainty was perceived as contra productive in view that this would lower the trust in the society.53 Several recommendations of the WHO and also ECDC were questioned, among them (i) contract tracing and isolating of contacts, (ii) spread of the disease by those with no symptoms (presymptomatic and asymptomatic spread), (iii) use of face-masks, (iv) border control.

|

Communication of uncertainty was often lacking especially in the first phase of the pandemic. Communication presented decision making as ‘following the science’, but imperfect data and uncertainty were not always communicated clearly (on personal protection equipment supply, transmission level, school transmission). Initial lack of transparency of information, including restricted SAGE meetings minutes and SAGE membership which feeds uncertainty and secrecy in decision making process.124

|