Abstract

Background

Enhancing health equity is endorsed in the Sustainable Development Goals. The failure of systematic reviews to consider potential differences in effects across equity factors is cited by decision‐makers as a limitation to their ability to inform policy and program decisions.

Objectives

To explore what methods systematic reviewers use to consider health equity in systematic reviews of effectiveness.

Search methods

We searched the following databases up to 26 February 2021: MEDLINE, PsycINFO, the Cochrane Methodology Register, CINAHL, Education Resources Information Center, Education Abstracts, Criminal Justice Abstracts, Hein Index to Foreign Legal Periodicals, PAIS International, Social Services Abstracts, Sociological Abstracts, Digital Dissertations and the Health Technology Assessment Database. We searched SCOPUS to identify articles that cited any of the included studies on 10 June 10 2021. We contacted authors and searched the reference lists of included studies to identify additional potentially relevant studies.

Selection criteria

We included empirical studies of cohorts of systematic reviews that assessed methods for measuring effects on health inequalities. We define health inequalities as unfair and avoidable differences across socially stratifying factors that limit opportunities for health. We operationalised this by assessing studies which evaluated differences in health across any component of the PROGRESS‐Plus acronym, which stands for Place of residence, Race/ethnicity/culture/language, Occupation, Gender or sex, Religion, Education, Socioeconomic status, Social capital. "Plus" stands for other factors associated with discrimination, exclusion, marginalisation or vulnerability such as personal characteristics (e.g. age, disability), relationships that limit opportunities for health (e.g. children in a household with parents who smoke) or environmental situations which provide limited control of opportunities for health (e.g. school food environment).

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted data using a pre‐tested form. Risk of bias was appraised for included studies according to the potential for bias in selection and detection of systematic reviews.

Main results

In total, 48,814 studies were identified and the titles and abstracts were screened in duplicate. In this updated review, we identified an additional 124 methodological studies published in the 10 years since the first version of this review, which included 34 studies. Thus, 158 methodological studies met our criteria for inclusion. The methods used by these studies focused on evidence relevant to populations experiencing health inequity (108 out of 158 studies), assess subgroup analysis across PROGRESS‐Plus (26 out of 158 studies), assess analysis of a gradient in effect across PROGRESS‐Plus (2 out of 158 studies) or use a combination of subgroup analysis and focused approaches (20 out of 158 studies). The most common PROGRESS‐Plus factors assessed were age (43 studies), socioeconomic status in 35 studies, low‐ and middle‐income countries in 24 studies, gender or sex in 22 studies, race or ethnicity in 17 studies, and four studies assessed multiple factors across which health inequity may exist.

Only 16 studies provided a definition of health inequity. Five methodological approaches to consider health equity in systematic reviews of effectiveness were identified: 1) descriptive assessment of reporting and analysis in systematic reviews (140 of 158 studies used a type of descriptive method); 2) descriptive assessment of reporting and analysis in original trials (50 studies); 3) analytic approaches which assessed differential effects across one or more PROGRESS‐Plus factors (16 studies); 4) applicability assessment (25 studies) and 5) stakeholder engagement (28 studies), which is a new finding in this update and examines the appraisal of whether relevant stakeholders with lived experience of health inequity were included in the design of systematic reviews or design and delivery of interventions. Reporting for both approaches (analytic and applicability) lacked transparency and was insufficiently detailed to enable the assessment of credibility.

Authors' conclusions

There is a need for improvement in conceptual clarity about the definition of health equity, describing sufficient detail about analytic approaches (including subgroup analyses) and transparent reporting of judgments required for applicability assessments in order to consider health equity in systematic reviews of effectiveness.

Plain language summary

How effects on health equity are assessed in systematic reviews of effectiveness

Key message

We found five methodological approaches to consider health equity in systematic reviews of effectiveness but the most appropriate way to address any of these approaches is unclear.

Review question

We reviewed the methods that systematic reviewers use to consider health equity in systematic reviews of effectiveness.

Background

Reducing health inequities, avoidable and unfair differences in health, has achieved international political importance and global endorsement. Decision‐makers have cited a lack of equity considerations in systematic reviews, creating a need for guidance on the advantages and disadvantages of methods to assess effects on health equity in systematic reviews.

Study characteristics

We included empirical studies of collections of systematic reviews that assessed methods for measuring effects on health inequalities. We define health inequalities as unfair and avoidable differences across socially stratifying factors that limit opportunities for health. We evaluated differences in health across any component of the PROGRESS‐Plus acronym, which stands for Place of residence, Race/ethnicity/culture/language, Occupation, Gender or sex, Religion, Education, Socioeconomic status, Social capital. "Plus" stands for other factors associated with discrimination, exclusion, marginalisation or vulnerability such as personal characteristics (e.g. age, disability), relationships that limit opportunities for health (e.g. children in a household with smoking parents) or environmental situations which provide limited control of opportunities for health (e.g. school, food, environment).

Key results

This updated review includes 158 collections of systematic reviews: 108 focused on evidence relevant to populations experiencing inequity, 26 assessed subgroup analysis across PROGRESS‐Plus, two assessed analysis of a gradient in effect across PROGRESS‐Plus and 20 used a combination of subgroup analysis and focused approaches. The most common PROGRESS‐Plus factors assessed were age (43 studies), socioeconomic status (35 studies), low‐ and middle‐income countries (24 studies). Four studies assessed multiple factors across which health inequity may exist.

We identified five methodological approaches to consider health equity in systematic reviews of effectiveness: 1) descriptive assessment in the reviews, 2) descriptive assessment of the studies included in the reviews, 3) analytic approaches, 4) applicability assessment, and 5) stakeholder engagement. However, the most appropriate way to address any of these approaches is unclear. Analysis of effects for specific populations need to be justified and reported appropriately to allow assessment of their credibility. Transparency of judgments about applicability and relevance to disadvantaged populations needs to be improved. Guidance on equity and specific populations is available in the Cochrane Handbook.

Search date

The evidence is up to date to February 2021.

Background

Health differences between groups may be due to inequalities in factors such as socioeconomic characteristics. Health inequalities that are unfair and avoidable are classed as health inequities. Health inequities persist, and are worsening, across almost all health problems, both within and between countries. For example, people living in the poorest countries have a life expectancy that is at least 30 years shorter than for people living in the richest countries. Within low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMIC), the mortality rate of children younger than five years is 64.6 deaths per 1000 births among the poor and 31.3 per 1000 among the rich (Chao 2018). In an update on global trends on child mortality, inequality in under‐five mortality between high‐ and low‐income regions is increasing as it is estimated that sub‐Saharan Africa will bear 60% of the global burden of under‐five deaths by 2050 (UN IGME 2018).

The World Health Organization (WHO) convened the Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) in 2006 and released its final report in 2008 to assess the evidence on taking action on reducing health inequity (Marmot 2008). The CSDH defined health inequity as "the poor health of poor people" both within countries and between countries as due to an "unequal distribution of power, income, goods, and services, globally and nationally, the consequent unfairness in the immediate, visible circumstances of people’s lives—their access to health care and education, their conditions of work and leisure, their homes, communities, towns, or cities—and their chances of leading a flourishing life" (Marmot 2008).

Such health inequalities need to be addressed, not only for moral and ethical reasons, but also for economic reasons (Sachs 2001). There is an increasing evidence base on the effectiveness of interventions for reducing health inequities, both within and between countries, as well as methods to evaluate health equity in systematic reviews, such as the Cochrane Handbook chapter on equity and specific populations (Welch 2021), and other guidance focused on considering inequalities in health (Maden 2018).

There is increasing acceptance that systematic reviews of the best available evidence are the foremost source of information on which to base evidence‐informed policy and practice (Lavis 2009,Kayabu 2013, White 2019). This view has been endorsed by a World Health Assembly resolution, which was based on the Mexico Ministerial Statement on Health Research (58th World Health Assembly Resolution). A similar recommendation emerged during the Role of Science in the Information Society health conference (European Organization for Nuclear Research 2003) that was held as part of the World Summit of the Information Society in December 2003. The recommendation stressed the need for reliable evidence delivered in a timely manner and in the right format. Systematic reviews are a useful basis for decision‐making because they reduce the chance of being misled, increase confidence in results, and are an efficient use of time (Lavis 2006).

Studies of policy maker perceptions found that policy makers increasingly consider systematic reviews as a useful source of knowledge to support decision‐making (Pope 2006,Kayabu 2013). However, decision‐makers are interested not only in what works, but also in the costs and resources involved in implementation and ensuring continuity, the potential harms or adverse effects, and the distribution of benefit across sociodemographic factors (Lavis 2005). The lack of evidence on the distribution of effects and impact on health equity has been highlighted by policy makers as a major barrier to the use of systematic reviews as a basis for decision‐making (Petticrew 2004, Vogel 2013). Unequal benefits or harms across different socioeconomic or demographic population groups could contribute to worsening health equity (Tugwell 2006). In the context of reducing health inequities, decision‐makers from diverse organisations may be interested in evidence of effects of interventions on reducing health inequity such as non‐governmental organisations and human rights organisations, as well as government decision‐makers in ministries of health and other departments (e.g. financial and agricultural) (Marmot 2008).

Health inequities are defined by Margaret Whitehead as “differences in health which are not only unnecessary and avoidable but, in addition, are considered unfair and unjust” (Whitehead 1992). Assessing the effects of interventions on health equity is difficult because it requires a subjective judgment about both the avoidability and the fairness of the distribution of effects (Kawachi 1999). Hence, assessments of the distribution of effects of interventions across groups of people who may experience health inequities in both clinical trials and systematic reviews focus on differences in health effects that can be measured (Arblaster 1996; Gepkens 1996).

The Campbell and Cochrane Equity Methods Group has adopted the acronym PROGRESS‐Plus to identify dimensions across which health inequities may exist: place of residence (e.g. urban/rural), race/ethnicity/culture/language, occupation, gender and sex, religion, education, socioeconomic status (SES), and social capital (Evans 2003; O'Neil 2014; Tugwell 2006). The "Plus" in PROGRESS‐Plus refers to any additional factors across which health inequalities may exist such as age, disability, and sexual orientation (Kavanagh 2008). The "Plus" could also include factors such as the experience of sexual or physical abuse as a child, which may shape the experience of health inequity later in life.

Despite the demand for equity assessment by policy makers, these assessments are rare in systematic reviews. The first version of this systematic review of methods to assess health equity, published in 2010, found that systematic reviews described the population by PROGRESS factors for only 0% to 57% of reviews, with sex distribution of the population being the most commonly reported factor. For the methodology studies with approaches to analyse or judge applicability of findings across PROGRESS‐Plus, there was insufficient detail to judge the credibility of these analyses or judgments (Welch 2010N).

Description of the methods being investigated

In this review, we investigated the different methods used to describe and assess effects on health inequalities in systematic reviews. Because health equity requires a subjective judgment about whether differences in health outcomes are unfair, we focused on the assessment of health inequalities across PROGRESS‐Plus factors (O'Neil 2014). We chose PROGRESS‐Plus as an organising framework to assess dimensions across which health inequities exist since it is endorsed by the Campbell and Cochrane Equity Methods Group and also encompasses the factors suggested by the World Health Organization Commission on Social Determinants of Health (Tugwell 2010). We also assessed whether the authors of the included studies described inequalities in health outcomes as unfair and unjust.

There are a number of ways to measure health inequalities. For example, health inequalities can be expressed as the difference between the most and least advantaged groups in relative or absolute terms (Keppel 2005), or they can be expressed using more complicated indices such as the Gini index, concentration index (Koolman 2004), or benefit‐incidence estimate (Wagstaff 2005). The choice of method and comparator or reference group influences both the magnitude of the result and its interpretation (Keppel 2005). See Table 1 for selected methods of assessing effects on health inequalities.

1. Selected methods of assessing effects on health inequalities.

| Method | Calculation |

| Targeted approach | Evaluation of effect size in the disadvantaged population only (e.g. Cochrane Review on community animal health services for improving household wealth and health status of low income farmers by Curran 2006). |

| Relative difference (gap approach) | (advantaged ‐ disadvantaged)/advantaged |

| Absolute difference (gap approach) | advantaged ‐ disadvantaged |

| Gradient‐approach regression | Regression‐based index of relative effect across incremental categories of disadvantage. |

| Gradient‐concentration index | Twice the area between the concentration curve and the line of equality (45 degrees line), defined with reference to the concentration curve, which graphs health status on the y‐axis against categories of disadvantage on the x‐axis (World Bank). |

| Gradient or gap‐benefit incidence | Computes the distribution of public expenditure across different PROGRESS‐Plus groups according to actual utilization of services. |

| Gradient approach ‐ Gini index | Measure of inequality of income distribution, defined as the area between the line of equality and the Lorenz curve, with categories of PROGRESS on the x‐axis and percentage of total income on the y‐axis (Gastwirth 1972). |

PROGRESS‐Plus: Place of residence (urban/rural), Race/ethnicity, Occupation, Gender, Religion, Education, Socioeconomic status, and Social capital. "Plus" includes any other factors that are associated with decreased opportunities for good health such as age, disability, disease status or sexual preference.

How these methods might work

Relative or absolute differences for health inequalities measured over time can demonstrate either an increase or decrease in health inequalities for the same data, because relative measures are affected by the underlying rate of the reference group. A detailed example of this can be found in Table C of Keppel 2005. Economic measures of health inequalities, such as the Gini index, concentration index, and the benefit‐incidence ratio, may be too complex to interpret and require too many data points to be useful in the context of systematic reviews (Tugwell 2006). This methodology review sought to assess whether these methods have been used to assess health inequalities in empirical studies analysing systematic reviews, and to explore the advantages and disadvantages of each method.

Why it is important to do this review

Despite the demand for health equity assessment in systematic reviews by policy makers and practitioners, there remains little empirical evidence on which of the different methods available for assessing health inequalities are have been used in the context of systematic reviews of effectiveness, and their advantages and disadvantages.

With the development of the PRISMA‐Equity extension in 2012 (Welch 2012a), there are now reporting guidelines for systematic reviews that are focused on equity. Furthermore, the discourse of equity is now more prominent than it was in 2010. In 2016, the United Nations Development Program adopted a list of 17 Sustainable Development Goals in order to reduce poverty and improve equality worldwide. All 17 goals are related to social determinants of health and the following 10 are strongly relevant to PROGRESS‐Plus and how equity issues affect healthcare outcomes (United Nations Development Programme 2015):

Goal 1: End extreme poverty

Goal 2: End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture

Goal 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well‐being for all ages

Goal 4: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education

Goal 5: Gender equality

Goal 6: Ensure clean water and sanitation for all

Goal 8: Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all

Goal 10: Reduce inequality within and among countries

Goal 13: Combat climate change

Goal 16: Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels

Objectives

To explore what methods are used by systematic reviewers to consider health equity in systematic reviews of effectiveness, and to assess advantages, disadvantages and feasibility of these methods.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included empirical studies of a cohort (more than one) of systematic reviews of health or non‐health interventions that assess effects on health across one or more socioeconomic and demographic factors defined by PROGRESS‐Plus. The empirical studies needed to assess whether authors of the included systematic reviews presented or discussed results on the effects of interventions for groups of people who could be classified as suffering from health inequity, across one or more of the factors of PROGRESS‐Plus. Empirical studies using qualitative or quantitative approaches were eligible.

Empirical studies could assess the effects of interventions that aim to decrease the category of health inequity experienced by a group of people, such as interventions which aim to improve education opportunities or reduce poverty, if they measured effects on health outcomes of these interventions (Gakidou 2010). An example of an eligible study is an empirical study which assessed the health effects of community‐based tobacco control interventions for groups of people who could be defined as experiencing health inequity across sex, race/ethnicity or socioeconomic status (SES) in six Cochrane Reviews (Ogilvie 2004).

We excluded individual systematic reviews assessing health inequalities as we aimed to assess methods for comparing health inequalities across different systematic reviews, rather than within an individual systematic review. Furthermore, including individual systematic reviews might introduce bias because they are less likely to report health inequalities analyses when no substantive differences are found (Chan 2004).

Overviews of systematic reviews synthesise evidence from multiple systematic reviews of interventions into one document (Higgins 2021). Overviews of systematic reviews were eligible if they assessed effects of interventions for groups of people who could be classified as experiencing health inequity.

Types of data

We assessed data from published or unpublished empirical studies of a cohort of systematic reviews on the advantages, disadvantages and feasibility of methods used to assess effects of interventions in groups of people who could be defined as experiencing health inequity. We extracted data on the advantages and disadvantages (or strengths and limitations) of each of the methods as described by the authors of the empirical studies. We used PROGRESS‐Plus to categorise groups of people who might experience health inequity. The place of residence of high‐income country compared to low‐ and middle‐income country was also considered as a factor across which health inequity may exist. We used the classification of the World Bank for high‐, middle‐ and low‐income countries. Since the political climate of a country interacts with the income level of the country in relation to the existence of health inequities, we considered differences in political stability and climate in the "Plus" factor of PROGRESS‐Plus. For example, although Saudi Arabia is a high‐income country, the experience of health inequity by religious groups and women is different than in a Western industrialised country.

For the health inequalities to be judged inequitable, unfairness and avoidability (or remediability) need to be assessed. Therefore, we assessed whether the empirical studies of cohorts of systematic reviews included a judgment about the fairness and avoidability of health differences. If the studies made no judgment about health equity, we used the Whitehead criteria of avoidability and unfairness to make a judgment about whether health differences across these factors for the particular intervention and setting could be considered health inequities (Whitehead 1992). Judgments made using these criteria were documented, including whether sufficient information was available to make such a decision. For example, sex differences that are due to unavoidable underlying differences in biology would not meet the criteria for a health inequity, such as differences in rates of breast cancer across sex, or manifestations of haemophilia in males (Whitehead 1992). We expected substantial heterogeneity in definitions of equity. Therefore, we documented the variety of existing definitions to help inform the development of universally accepted definitions.

Empirical studies of cohorts of systematic reviews were included if they focused on the following.

Targeted approaches: evaluating effects (benefits or harms) in disadvantaged populations only (i.e. populations who suffer from health inequity across socially stratifying characteristics defined by one or more of the PROGRESS‐Plus factors).

Gap approaches: evaluating differences in effects (benefits or harms) between the most and least advantaged groups (see Table 1).

Gradient approaches: evaluating effects (benefits or harms) on the gradient from the most disadvantaged to the least disadvantaged groups (Table 1).

We use the term "disadvantaged" to indicate people and groups of people who are denied opportunities for health due to structural and systemic maldistribution of power and resources in society. We recognise that different groups of people may use different terms to define their situation such as under‐served, marginalised, socially excluded or stigmatised.

Types of methods

We compared different methods used by the empirical studies for considering health equity in terms of: the expertise required to implement the strategy at the level of the overview/empirical study; the availability of data from the systematic reviews as assessed by the authors of the empirical study; their advantages and disadvantages; and whether and how judgments about health equity were made (e.g. judgments about fairness and avoidability of differences in benefits or harms).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Advantages and disadvantages of the methods used for assessing health inequalities, based on descriptions of the authors of the empirical studies and a judgment by the data extractors assessed from the perspective of a user of the empirical study. This judgment was made by asking the data extractors to consider a decision‐maker's perspective. These judgments were compared and agreed to. We also discussed these judgments with other authors who were not responsible for the data extraction.

Whether the analyses of effects on health inequalities across PROGRESS‐Plus factors met the following criteria for credible subgroup analyses, as recommended by the Cochrane Handbook (Oxman 1992, Higgins 2021).

Clinically important difference.

Statistically significant difference.

A priori hypothesis.

Subgroup analysis is one of a small number of hypotheses tested.

Difference suggested by comparisons within primary studies of meta‐analyses.

Difference consistent across primary studies of meta‐analyses.

Indirect evidence that supports hypothesised difference.

Four additional criteria for credibility of subgroup analyses were proposed since the protocol for this review (Welch 2009) was written for assessing the credibility of subgroup analyses: 1) consideration of baseline characteristics; 2) independence of the subgroup effect (i.e. the subgroup effect is not confounded by association with another factor); 3) a priori specification of the direction of effect; and 4) consistency across related outcomes (Sun 2010). These four criteria are included in this updated review.

Secondary outcomes

Whether and how health inequity was defined and measured (e.g. whether proxy measures, such as nutritional status, were used).

Information on the availability of data from primary trials or meta‐analyses to conduct analyses across PROGRESS‐Plus factors.

What factors are associated with health inequalities (e.g. implementation factors, such as the degree to which flexibility was allowed in the implementation).

Implications for practice, policy, and research based on analysis of effects on health inequalities.

Search methods for identification of studies

The search strategy was developed by one review author (VW) using a systematic scoping exercise to assess the effects of different MeSH terms and the use of limits on publication type (i.e. limited to meta‐analyses or systematic reviews) and type of studies (i.e. intervention studies). The terms developed for equity were based on the elements of PROGRESS‐Plus, and testing that our group has done on the use of filters for health equity (McGowan 2003). We tested the inclusion of a term related to geographic disparities (including terms such as resource‐poor settings and low and middle‐income countries) because the search was very broad without using restrictions. We tested this strategy to ensure that known relevant studies were retrieved, including one study of the assessment of low‐ and middle‐income country concerns in systematic reviews (Nasser 2007). The final search strategy does not include limitations on publication type as these were found to be too restrictive. An information scientist (JM) reviewed the search strategy, as recommended by the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) guidelines (Sampson 2008).

The search strategy was not limited by publication type or study design as there is no indexing term for studies that assess cohorts of systematic reviews. We included published and unpublished articles, as well as abstracts.

Electronic searches

We searched:

the Cochrane Methodology Register (to 31 May 2012, after which it was discontinued)

MEDLINE (January 1950 to 26 February 2021) using the Ovid interface

Embase (1980 to 26 February 2021) using the OVID interface

PsycINFO (1806 to February, Week 4, 2021) using the OVID interface

CINAHL (1998 to 2 March 2021)

See Appendix 1 for the MEDLINE search strategy.This search strategy was adapted for the other electronic databases (Appendix 2).

To identify systematic reviews of social, legal, and educational interventions, we searched non‐health literature databases using the Scholars Portal interface including the Education Resources Information Center (ERIC, 1965 to January 2021), Education Abstracts (1983 to 2 July 2010. Note: this database was discontinued since the first version of this review so it was not included in the update search), Criminal Justice Abstracts (1968 to 2 March 2021), Index to Foreign Legal Periodicals (1994 to 2 March 2021), PAIS International (public affairs, public and social policies, international relations ‐ 1972 to 4 March 2021), Social Services Abstracts (1979 to 4 March 2021), Sociological Abstracts (1952 to 4 March 2021), and Digital Dissertations (1997 to 2 July 2010. Note: this database was discontinued since the original review thus was not updated). We also searched the reports of national health technology assessment organisations using the Health Technology Assessment Database (available on the Cochrane Library) to 10 May 2017 (note: it was discontinued after this date).

Through our search process, we discovered that the Digital Disserations and Educational Abstracts databases no longer existed. The original search strategies were used for all databases except for ERIC, which migrated to the OVID interface since the original review. The original ERIC search strategy was altered to fit the OVID interface and can be found in Appendix 2.

Searching other resources

We also handsearched abstracts from Cochrane and Campbell Collaboration Colloquia (2007 to June 2021).

We used SCOPUS to identify citations of potentially included studies. SCOPUS is a citation tracking database of over 18,000 titles across scientific, technical, medical and social sciences fields as well as arts and humanities. We conducted a search of SCOPUS for all included studies on 10 June 2021. This identified any articles which had cited one or more of the included studies.

We checked the reference lists of included studies using an automated method (https://www.lens.org/) to identify other potentially relevant studies.

We also asked the editorial board members of the Cochrane and Campbell Equity Methods Group whether they were aware of other potentially relevant studies.

Unpublished studies and abstracts were identified through the above methods of contacting experts, authors and searching conference proceedings of the Cochrane and Campbell Colloquia.

We contacted all authors of studies identified from 2010 onwards to ask whether they were aware of any potentially relevant methodology studies. We received 27 responses and a total of 31 suggested reviews.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (chosen from EU, JdM, MB, BD, VW, KM, WM, JT, CM, AR, WM, AA, SA, AAM, VB, OD, KK, MTM, HAP, and EG) independently screened the titles and abstracts of all references retrieved by the search strategy to exclude those that were obviously irrelevant. They were not blinded to the authorship of the titles and abstracts because this is difficult to achieve and may not affect the screening process (Berlin 1997).

Potentially relevant articles were retrieved and screened independently by two review authors (chosen from EU, JdM, BD, MB, VW, WM, KM, JT, CM, AR, WM, AA, SA, AAM, VB, OD, KK, MTM, HAP, and EG) using an eligibility checklist. Disagreements were resolved by consensus in consultation with another review author (MP, PT, VW, OD, EG or AR). We documented all reasons for exclusion at both stages of screening for entry into a PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta‐Analyses) flowchart (Moher 2009).

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (chosen from EU, JdM, MB, VW, CM, WM, KM, JT, CM, AR, WM, AA, SA, AAM, VB, OD, KK, MTM, HAP, and EG) extracted data independently from the included empirical studies using a pre‐tested data extraction form designed in an Excel spreadsheet (see Appendix 3), which was used to manage and summarise data. For consistency, VW or JT extracted data from each study. The assignment of articles to the other data extractors was based on their time available to contribute. We compared the data extracted by both review authors for each study. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. Another author (MP, PT, VW, OD, EG, or AR) mediated when consensus could not be reached.

We extracted data on:

how the sample of systematic reviews was selected;

the characteristics of the systematic reviews (population, intervention, comparison, outcomes, study designs included, quality assessment, year of publication);

characteristics of the interventions being studied (e.g. pharmacologic, implementation, health services);

the method used to consider health equity in systematic reviews of effectiveness (how and whether equity is defined; which elements of PROGRESS‐Plus were compared; whether other factors, such as the study design of primary studies, setting, or context, were assessed that might explain differences in effects across PROGRESS‐Plus factors);

how effects were compared (e.g. relative or absolute differences, or gradient approaches such as the Gini coefficient);

the size of the difference in effects across different populations defined by PROGRESS‐Plus.

We also assessed whether data on PROGRESS‐Plus were available from the systematic reviews, as reported by the authors of the empirical studies. We did not verify these data availability by consulting the systematic reviews.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two of the four possible reasons for systematic error or bias were addressed: selection bias and detection bias (Boutron 2021). For each of these possible sources of bias, we assessed the transparency of the methods described by the authors and the potential for bias in the methods used to select and analyse the systematic reviews included in the cohort. We did not assess performance bias as this is related to exposure to the intervention in randomised controlled trials and does not apply to empirical studies of cohorts of systematic reviews. In the context of empirical studies designed to assess health inequalities in cohorts of systematic reviews, selection and detection bias were defined as follows.

Selection bias: potential for bias in the selection of the systematic reviews to be included or excluded. We extracted details on the inclusion and exclusion criteria used to select systematic reviews.

Detection bias: potential for bias in the assessment of analytic methods and outcomes in cohorts of systematic reviews. We extracted information on how the details of how health equity was considered were extracted from the systematic reviews.

We did not assess attrition bias because in the context of this review, attrition bias (defined as systematic differences between groups in withdrawals) refers to the same concept as selection bias.

Measures of the effect of the methods

We conducted a comparative analysis of the methods used to assess effects on health inequalities by comparing the advantages and disadvantages of each of the methods, as judged by the data extractors, based on the description by the authors of the empirical studies and considering the perspective of the reader or user of the empirical study.

We extracted details reported by the authors of the empirical studies on the availability of data from the systematic reviews and their included studies, as well as on the methods used to compare differences in disadvantaged populations to the overall pooled effect.

We also compared any subgroup analyses against 11 criteria for credible subgroup analyses (Oxman 1992, Sun 2010). Two additional criteria for subgroup analyses for clinical trials and meta‐analyses were also considered for this comparison of a test for subgroup by treatment interaction and whether trials stratified by subgroup (Rothwell 2005; Thompson 2005).

Unit of analysis issues

.

Dealing with missing data

We planned to contact authors of the included studies if insufficient information was available regarding sample generation, methods, and outcomes. We only contacted one author for additional information, to request the criteria used to assess applicability and equity (Althabe 2008). These authors provided their checklists.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Results were not pooled. Results for each outcome (e.g. data availability, advantages, disadvantages, and credibility of subgroup analyses) were presented across each factor of PROGRESS‐Plus for each included study.

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting bias occurs when dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results (Boutron 2021). Positive studies, in the context of this review, include studies that are able to show statistically significant and substantive differences in effects across one or more PROGRESS‐Plus categories. We attempted to minimise the identification of only studies with positive results by using a comprehensive search strategy in diverse electronic databases, assessing relevant conference proceedings, reviewing citations, and contacting the authors of eligible empirical studies and other experts.

Data synthesis

Results were synthesised in tables. Where data were available on subgroup analyses, we summarised the methods used to compare effects in different populations across PROGRESS‐Plus categories. For subgroup analyses, we assessed the first criteria of clinical importance of the difference in effects by assessing whether the authors of the empirical study described the clinical importance. If the authors did not judge the clinical importance, we indicated that this was not assessed.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

As this is a descriptive methodology review, the results were not pooled and subgroup analyses were not conducted.

Sensitivity analysis

As this is a descriptive methodology review, the results were not pooled and sensitivity analyses were not conducted.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

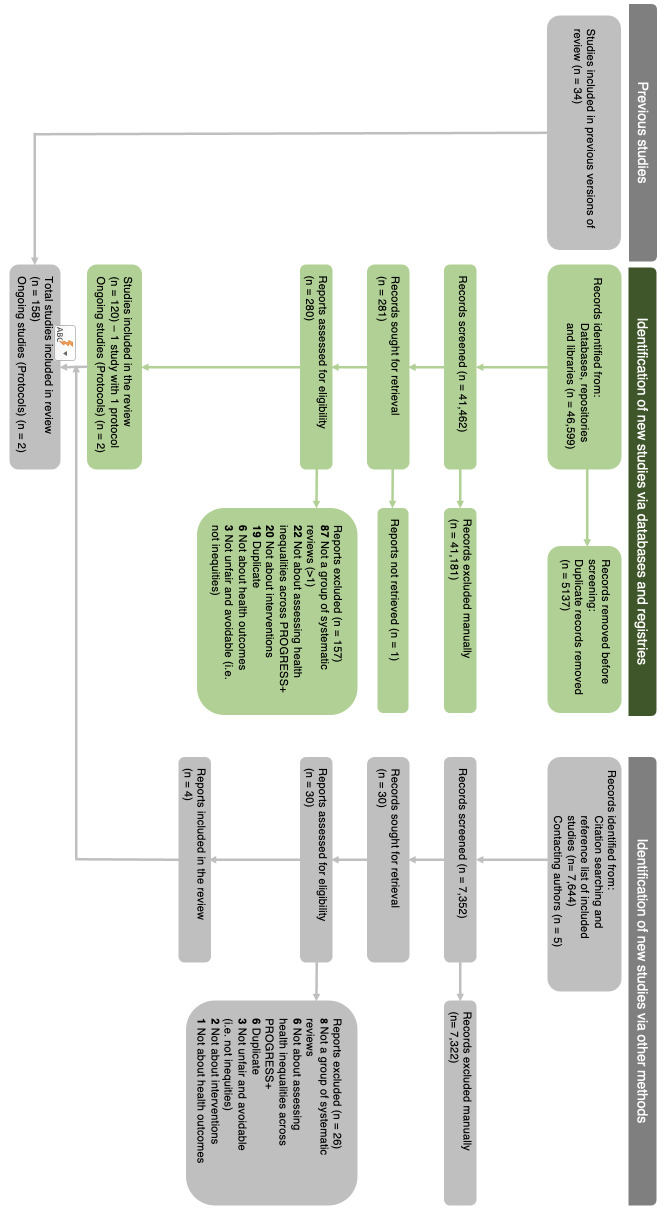

In total 10,058 potential articles were screened for inclusion up to 2 July 2010 for the first version of this review (Welch 2010). An additional 48,814 records were identified in the updated searches for screening (Figure 1). Of these, 310 potentially eligible studies were retrieved in full text.

1.

PRISMA flow chart

Included studies

We included 158 methodology studies in this review (Table 2). Thirty‐four were identified in the previous version of this review (Welch 2010). The included studies in this update were overviews (122 studies), methodology (25 studies), scoping reviews (eight studies) and evidence and gap maps (three studies). The median number of systematic reviews per study was 17 (range 2 to 1598). The studies were identified by searching electronic databases (123 studies), reference checking (15 studies), SCOPUS checking (nine studies), contacting authors (eight studies), and handsearching (three studies). Of the 158 included studies, 153 were published as full papers, and five were published only as abstracts. We identified two protocols for methodology studies which we have classified as ongoing studies.

2. Summary table of 158 methods study characteristics.

| Study Characteristics | 2010 review | 2021 update | total | |

| Type of Methodology study | Overview | 29 | 93 | 122 |

| Methodology | 7 | 18 | 25 | |

| Scoping review | 0 | 8 | 8 | |

| Evidence and Gap map | 0 | 3 | 3 | |

| Number of systematic reviews | Median and range | 21 (4 to 420) |

15 (2 to 1598) |

17 (2 to 1598) |

| Identified | Electronic databases | 19 | 104 | 123 |

| Reference checking | 3 | 12 | 15 | |

| SCOPUS search for citations | 9 | 0 | 9 | |

| Contacting authors | 2 | 6 | 8 | |

| Method of assessing equity | Gap | 12 | 14 | 26 |

| Gradient | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Targeted | 23 | 85 | 108 | |

| Targeted and gap | 0 | 22 | 22 |

The methods for evaluating health equity were classified as gap approaches which evaluated differences between groups across PROGRESS (26 studies), gradient approaches which assessed the relationship of effects to PROGRESS characteristics (two studies), studies which focused their search on specific populations defined across PROGRESS‐Plus (108 studies) and studies which used both a gap analysis and a focused approach (22 studies).

The dimensions of equity assessed are summarised in Table 3. The most commonly assessed dimension was age (either vulnerability of young or older people) in 30% of studies (47 studies), followed by gender or sex (37 studies, 23%), socioeconomic status (SES) (36 studies, 23%) and place of residence in a low‐ and middle‐income country (27 studies, 17%). In comparing the dimensions assessed in the 34 studies included in the previous version of this review and this update, there were relatively more studies assessing age (33% versus 18%) or health condition (18% versus 6%) as factors across which inequities are experienced, and fewer studies focused on LMIC settings (9% versus 47%).

3. PROGRESS Dimensions assessed in 158 methodology studies, separated by prior review (2010) and current update to 2021.

| PROGRESS dimensions assessed | Studies identified in the update (n=124) |

2010 review (n=34 studies) |

Total (n=158) |

||

| Focus | With other PROGRESS dimensions | Focus | With other PROGRESS dimensions | ||

| Place of residence(LMIC) | 4 (3%) |

7 (6%) |

13 (38%) |

3 (9%) |

27 (17%) |

| Place of residence (urban/rural or housing) | 0 | 12 (10%) |

0 | 1 (3%) |

13 (8%) |

| Race/ethnicity/culture/language | 2 (2%) |

7 (6%) |

1 (3%) |

6 (18%) |

16 |

| Occupation | 2 (2%) |

3 (2%) |

0 | 0 | 5 (3%) |

| Gender or sex | 9 (7%) |

17 (14%) |

3 (9%) |

8 (24%) |

37 (23%) |

| Religion | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Education | 0 | 2 (2%) |

0 | 3 (9%) |

5 (3%) |

| Socioeconomic status | 7 (6%) |

19 (15%) |

1 (3%) |

9 (26%) |

36 (23%) |

| Social capital | 0 | 2 (2%) |

0 | 0 | 2 (1%) |

| All of PROGRESS‐Plus | 12 (10%) |

‐ | 3 (9%) |

‐ | 15 (9%) |

| Plus‐Indigenous | 3 (2%) |

0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (2%) |

| Plus‐Age (either older or younger people) | 17 (14%) |

24 (19%) |

2 (6%) |

4 (12%) |

47 (30%) |

| Plus‐Health condition associated with inequities (e.g. disability, HIV, mental health, obesity) | 15 (12%) |

7 (6%) |

2 (6%) |

0 | 24 (15%) |

| Plus‐Features of relationships (e.g. children in school environment) | 6 (5%) |

0 | 0 | 0 | 6 (4%) |

Excluded studies

In the updated search, 183 out of 310 studies that were retrieved in full text were excluded. In total 240 studies were excluded since they clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria because they were not cohorts of systematic reviews (n = 133), or because they did not assess health inequalities across one or more PROGRESS‐Plus factor (n = 47), or were not about interventions (n = 22), duplicates (25), not about health outcomes (n = 7), not about inequities (3) and protocols (3). Eighteen studies which appeared to meet all inclusion criteria, but on closer examination failed, are described in the Characteristics of excluded studies.

Seven studies were excluded because they did not describe a focus on health equity (Barlow 2004; Craig 2003; Espinosa‐Aguilar 2007; Gaes 1999; Gulmezoglu 1997; Maden 2018, Proper 2019) (See Characteristics of excluded studies). These studies assessed health effects of interventions in specific populations that could be considered as socially disadvantaged across one or more PROGRESS‐Plus factor (e.g. sexual offenders, elderly, children with chronic disease,health promotion interventions at the workplace), but the study authors did not describe a focus on vulnerability or social disadvantage. Five studies of cohorts of systematic reviews were excluded because they did not assess health inequalities (Ahmad 2010, AHRQ 2010, Newman 2020, Nguyen 2020, Skelton 2020). Three studies that assessed health inequalities were excluded because they were a single systematic review of multiple interventions, not a cohort of systematic reviews (Thomas 2008, Lee 2016, Huntley 2017). One study was excluded because it was not possible to determine if it was a cohort of systematic reviews (Prabhakaran 2018). One study of equity in health technology assessment (HTA) identified as ongoing in the original review was excluded because, although HTA reports often include systematic reviews, it was not possible to assess the systematic reviews in this study (Panteli 2015). One systematic review of reviews assessed health effects of interventions to prevent HIV but mapped the evidence from included primary studies rather than the reviews (Krishnaratne 2016).

Risk of bias in included studies

From the reporting of each cohort, we assessed the risk of selection bias to be low for 128 out of the 158 included studies (Figure 2). These 128 studies reported using an explicit search method, and a prespecified criteria was used in screening titles for inclusion to identify relevant systematic reviews. Selection bias was assessed to be high in eight of the 158 included studies because of the absence of a systematic search or predetermined inclusion criteria. The remaining 22 studies have an unclear risk of bias as the methods for a systematic search and screening of studies are not fully reported.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Detection bias was low for 107 out of the 158 included studies which reported explicit methods of data extraction, using forms and data verification. Conversely, detection bias was assessed to be high in three of the 158 included studies. The remaining 48 studies have an unclear risk of bias as the methods for data extraction and verification are not fully reported, so these studies may be subject to a higher risk of bias due to missing relevant information.

Allocation

.

Blinding

.

Incomplete outcome data

.

Selective reporting

.

Other potential sources of bias

.

Effect of methods

Definition of health equity

Equity was defined in 16 studies, as unfair and avoidable inequalities in health across socioeconomic, demographic, or geographic strata (Bambra 2009; Bosch‐Capblanch 2017; Cairns 2014; Evans 2020; Halas 2020; Humphreys 2013; Lopez‐Alcalde 2019; Maden 2017; Nittas 2020; Odierna 2009; Tsikata 2003; Tugwell 2008; Welch 2013; O'Neil 2014; Welch 2012; Welch 2016). Seven other studies did not define equity but instead described a group of people that are disadvantaged or a condition that is unavoidable or unfair, for example population groups that are socioeconomically disadvantaged (Craike 2018), people living with HIV, mental illness, and physical disabilities (Jackson‐Best 2018), residents in long‐term care (McArthur 2017), violence against women and girls (Arango 2014), youth violence (Matjasko 2012), loneliness and social isolation (Boulton 2021), and in one case, described a condition which is necessary for health equity i.e. food security (Visser 2018). None of the studies described making a judgment about the fairness of differences in health. Thirteen studies describe higher burden of disease in disadvantaged populations as avoidable or preventable, with several other studies explicitly describing the preventability of age‐related inequities (Evans 2020; Mukamana 2016; Pundir 2020; Soler 2019), without making a statement about fairness or justice. Two studies described using an “equity lens” (Macintyre 2020; Main 2008) to assess whether systematic reviews could be used to answer questions about reducing health inequalities across SES, ethnicity or education. Three studies used the “SUPPORT equity checklist” (Althabe 2008; Chopra 2008; Lewin 2008) which assesses access to health care across LMIC, gender, age, ethnicity or socioeconomic status (SES) (Appendix 4). One study used an “equity focus” (Phillips 2017) which defines the extent to which an intervention focuses on particular disadvantaged populations. Six studies focused on assessing differences across gender or sex by conducting a gender analysis (Fitzgerald 2016; Johnson 2003; Sherr 2009) or gender and sex based analysis (Doull 2010; Lopez‐Alcalde 2019; Petkovic 2018). In one study, the rationale for conducting a gender analysis was due to differences in biological susceptibility to HIV/AIDS as well as the social susceptibility through gender roles and discrimination (Sherr 2009). Twenty‐four studies focused on assessing relevance of systematic reviews for decisions about health care in low and middle income countries (LMIC)(Barbosa Fihlo 2016; Bhutta 2009; Chopra 2008; Ciapponi 2017; Darmstadt 2009; Durao 2015; English 2017; Evans 2019; Evans 2020; Foss 2019; Haws 2009; Heidkamp 2017; Menezes 2009; Nasser 2007; Pantoja 2017; Phillips 2017; Pundir 2020; Questa 2020; Tsikata 2003; Tugwell 2008; Visser 2018; Witten 2017; Yakoob 2009; Yount 2017). Two of these studies described differences in access to health care across geography and SES in LMIC as inequitable (Chopra 2008; Lewin 2008).

Methods identified to assess consideration of effects on health inequalities or health inequities

We identified five categories of methods used to assess whether systematic reviews considered effects of interventions on health equity: 1) descriptive assessment of systematic reviews; 2) descriptive assessment of primary studies included in the systematic reviews; 3) analytic approaches, 4) judgment of applicability to disadvantaged populations or settings and 5) engagement of relevant stakeholders with lived experience of inequities to inform the design of systematic reviews or the intervention studies. See Table 4.

4. Methods used to assess whether health equity was considered in systematic reviews.

| Methods used to assess health equity effects | How many studies used this method | Data availability | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| 1a. Descriptive‐ SRs mention PROGRESS‐Plus | 18/158 Studies reporting data availability: 12 studies |

Place of residence LMIC (15/193 SRs); race/ethnicity (34/283 SRs); occupation (1/95 SRs); gender/sex (129/368 SRs); religion (1/95 SRs); education (0/95 SRs); SES (40/260 SRs); social capital (0/95 SRs), | Indicates whether authors of systematic reviews have considered health equity | Does not assess potential for differences across PROGRESS‐Plus factors or health inequalities |

| 1b. Descriptive‐ SRs describe population across PROGRESS‐Plus factor(s) | 110/158 61 Focused on specific population thus all SRs included that population |

Targeted to specific PROGRESS‐Plus factor: 61 studies SRs with mixed populations: Place of residence (213/723 SRs; 29%); race/ethnicity (94/1294 SRs; 7%); occupation (22/411 SRs; 5%); gender/sex (239/795 SRs;30%); religion (3/392 SRs; 1%); education (8/411 SRs; 2%); SES (99/580 SRs; 17%); social capital (9/398 SRs; 2%), Age (155/432 SRs, 36%); health condition and equity, 18/297 SRs; 6%) |

Provides direct data on whether different populations included in SRs which is useful for judging applicability | Does not analyse influence of population characteristics or setting on effects on health inequalities Data available for age in 36% of SRs, sex or gender in 30% of SRs, place of residence in 29% of SRs, others are available in less than 25% of SRs |

| 1c. Descriptive‐ SR describes if intervention is given only to disadvantaged populations across PROGRESS‐Plus | 118/158 | 65 studies were focused on a specific populations across one or more PROGRESS‐Plus characteristics 53 studies evaluated whether SRs included studies focused at specific populations across PROGRESS‐Plus |

Assesses if interventions have been tested in specific disadvantaged populations | Does not assess effects of intervention Can be misleading since SRs with no studies conducted in disadvantaged populations may still be relevant and applicable |

| 1d. Descriptive‐ Outcomes of SR related to equity of access | 25/158 SRs | Equity of access or coverage measured in 118/346 SRs. | Provides data on access to health care, a determinant of health inequalities | Data on access to care does not measure effects on health inequalities Measuring access to health care is dependent on the question and availability of data depends on selection criteria of methodology review |

| 1e. Descriptive‐ describe if SRs conduct or plan subgroup analyses across PROGRESS‐Plus | 58/158 | Analysis by PROGRESS‐Plus in SRs: Place of residence; 5/297 SRs (2%); Race/ethnicity (35/1104 SRs; 3%); Occupation (10/262 SRs; 4%); Sex or Gender (145/1365 SRs; 11%); Religion (1/243 SRs, 0%); Education (8/255 SRs; 3%); SES (90/729 SRs; 12%);Social capital (4/243 SRs; 2%), PROGRESS subgroup: 10/87 SRs, 11%) ; Age (36/381 SRs; 9%), Health condition (4/243 SRs; 2%), sexual orientation (1/19 SRs, 5%) |

Subgroup analysis provides direct data needed to answer whether the intervention works the same or differently in populations of interest | Lack of data: data available by PROGRESS‐Plus subgroups of interest in 10% of SRs (28/247 had data) |

| 2a. Descriptive‐ assess if primary studies describe population across PROGRESS‐Plus | 50/158 | Place of residence (270/1507 studies, 18%), race/ethnicity (150/1390, 11%), occupation (36/399 studies, 9%), gender or sex (883/1369 studies, 64%), religion (0/337, 0%), education (64/422 studies, 15%), SES (246/1026 studies, 24%), Social capital (25/399 studies, 6%), Age (303/963 studies, 31%), health conditions (0/87 studies), sexual orientation (0/87 studies) | Provides evidence on whether sufficient evidence is available from primary studies to conduct subgroup analyses in SRs | Data may not be available stratified by PROGRESS‐Plus factors in the primary studies |

| 2b. Descriptive‐ assess if primary studies stratified analyses by PROGRESS‐Plus | 28/158 studies | 50/158 | Place of residence (270/1507 studies, 18%), race/ethnicity (155/1430, 11%), occupation (36/399 studies, 9%), gender or sex (883/1369 studies, 64%), religion (0/337, 0%), education (64/422 studies, 15%), SES (246/1026 studies, 24%), Social capital (25/399 studies, 6%), Age (303/963 studies, 31%), health conditions (0/87 studies), sexual orientation (0/87 studies) | Time‐consuming to assess all primary studies of included SRs Does not rule out the possibility of spurious statistical significance |

| 3a. Analytic: association | 9/158 studies | Association of PROGRESS factors with effects in 6 studies. [factors included: Place of residence, race/ethnicity/culture/language, Occupation, gender or sex, Education, SES, social capital, age 2 studies used Harvest Plots to assess positive gradient, negative gradient or no gradient across PROGRESS factors |

Indicates whether PROGRESS‐Plus factors are associated with different relative effects Could be used to assess gradients of effect modification according to different levels of PROGRESS‐Plus (e.g. poverty) |

Data availability may be a limitation |

| 3b. Analytic: relative comparison of effect size in two groups using an odds ratio | None | |||

| 3c. Analytic: assess effects in a disadvantaged population | 108/158 focused on specific populations experiencing inequity across PROGRESS‐Plus | Place of residence‐LMIC: 16 Place of residence‐ housing: 1 Race/ethnicity/culture/language: 2 Occupation: 2 Gender or sex: 4 Religion: 0 Education: 0 Socioeconomic status: 4 Social capital: 0 Plus Indigenous: 3 Age: 16 Health conditions: 19 Relationships/environment: 6 Note: 35 studies focused on populations experiencing inequity across two or more determinants |

Directly applicable for decisions about interventions in these specific disadvantaged populations Identifies evidence gaps |

Lack of data in some disadvantaged populations limits the use of this approach for other populations and settings Low methodological quality of SRs may limit applicability Lack of data on process of implementation |

| 4a. Applicability: assess likely impact on disadvantaged populations using checklists for applicability and equity | 17/158 studies | Applicability checklist: 1 study Used absolute risk to extrapolate impact in low income countries: 1 study Biological plausibility, impact and feasibility in LMIC (see Appendix 7): 2 studies Feasibility or applicability in low‐resource settings (no specific tool): 2 studies SUPPORT tools: 1 study SIGN tools: 4 studies GRADE certainty: 4 studies Programme theory to understand differential effects across SES: 2 study |

Useful summary for policy‐makers about likely relevance in specific populations and settings Standardized format makes judgments explicit and transparent Does not require replication of studies in different populations and settings Not subject to statistical power issues of subgroup analyses |

Does not assess the magnitude of effect in different populations Requires content and methodological expertise to make equity and applicability judgments Low availability of data to make judgments (Althabe 2008), (Lewin 2008), (Chopra 2008) |

| 4b. Assess stakeholder engagement with populations experiencing inequity | 28/158 studies | 16 studies reported that stakeholders were engaged in the design of the methods study (e.g. patients, Indigenous people, children with disability) 12 studies evaluated whether systematic reviews reported stakeholder engagement in the primary studies, e.g. in designing or the interventions |

Provides perspectives and priorities of populations experiencing inequity in designing the study and interventions Inclusive process with intended beneficiaries of research is needed for transformative research |

Time‐consuming to build authentic partnerships and ensure equitable and meaningful engagement |

SES: Socioeconomic status; PROGRESS: PROGRESS: Place of residence (urban/rural), Race/ethnicity, Occupation, Gender, Religion, Education, Socioeconomic status and Social Capital

1) Descriptive assessment of systematic reviews

All but 18 studies used at least one of the five descriptive approaches described below to assess whether their sample of systematic reviews had considered effects of interventions on health equity.

1a) Mention of PROGRESS‐Plus in introduction, objectives, discussion, implications

Only 18 methodology studies included in their objectives the assessment of explicit mention of PROGRESS‐Plus in the introduction, objectives or discussion of the included systematic reviews. The dimensions assessed are described in Table 4. This strategy provides information about whether systematic reviews consider health equity in a broad sense, but provides no evidence on potential differences in effects across PROGRESS‐Plus factors..

1b) Methodology study to assess whether systematic reviews describe populations in the primary studies across PROGRESS‐Plus factors

Description of populations across PROGRESS Plus in primary studies was assessed by 110 out of 158 studies. Sixty‐one of these studies were focused on specific populations, thus all systematic reviews described the population characteristic of interest. For the studies which included mixed populations, details on PROGRESS‐Plus for people included in the trials were available for 2% to 36% of systematic reviews across PROGRESS‐Plus factors. Age distribution (reported in 36%, 155 out of 432 systematic reviews) and sex distribution (reported in 30%, 239 out of 795 systematic reviews) of the population were the most well‐reported PROGRESS‐Plus factors. The advantage of this approach is that information about the diversity of populations increases confidence in applying results across different populations and settings. The disadvantages are lack of data, and that description of populations does not assess differences in effects across these populations.

1c) Methodology study to assess whether systematic reviews describes primary research as targeted at disadvantaged populations across PROGRESS‐Plus

One hundred and eighteen (75%) methodology studies assessed whether systematic reviews described interventions as being evaluated in specific disadvantaged populations. Of these, seven restricted their focus to those systematic reviews examining disadvantaged populations (targeted).

Sixty‐five methodology studies selected systematic reviews which focused only on disadvantaged populations. The populations in these methodology studies included low‐ and middle‐income country settings (Nasser 2007, Heidkamp 2017), ethnicity, occupation (healthcare workers), elderly with mental health problems (Adamek 2008; Bartels 2003, Legere 2018), youth with disabilities (Stewart 2006, Bailey 2015), socially disadvantaged mothers (D'Souza 2004), women at risk for low birth weight children (Ball 2002), and minority populations, injection drug users and people with HIV (Vergidis 2009). Dimensions of inequity that were identified in this update included methodology studies focused on Indigenous people (Chamberlain 2017, Gomersall 2016), older people with long‐term conditions or their caregivers (Duan‐Porter 2016, Boulton 2021, Jarvis 2020), people in relationships leading to inequities such as children in low‐income neighbourhoods or school environments (Flay 2009), or temporary situations such as discharge from hospital (Strasßner 2020). These methodology studies described these populations as disadvantaged because of avoidable and unfair poorer health outcomes than other people due to lack of evidence, lack of guidelines or lack of resources to access and use preventive and curative interventions. Fifty‐three methodology studies reported assessing whether the systematic reviews described at least one study conducted in a specific disadvantaged population. While this descriptive method identifies whether interventions have been evaluated in disadvantaged populations, it does not assess the effects on health inequalities. Furthermore, it can be misleading since systematic reviews with no studies in disadvantaged populations may still be relevant and applicable to disadvantaged populations.

1d) Methodology study to assess whether systematic reviews have outcomes related to equity of access

Twenty‐five methodology studies (16%) described whether systematic reviews reported outcomes related to access to care or coverage of health services. For the studies which reported data availability, access to health care across disadvantaged groups (e.g. rural, low SES, LMIC, ethnicity) was reported in 118 out of 346 systematic reviews in these methodology studies. Access to health care is a determinant of both health and health inequalities. This strategy does not measure potential differences in effects across PROGRESS‐Plus factors. Evidence on access to care may be affected by the eligibility criteria of the methodology studies. For example, one methodology study required that systematic reviews contain information about access to care in LMICs by the focus of the review (Lewin 2008).

1e) Methodology study to assess whether systematic reviews planned or conducted subgroup analyses across one or more PROGRESS‐Plus factors

Fifty‐eight methodology studies (37%) assessed whether subgroup analysis was conducted in groups of systematic reviews. Outcomes were analysed using subgroup analysis across one or more PROGRESS‐Plus factor in only 22 (8%) out of 262 systematic reviews assessed in these methodology studies. For those that reported details of these subgroup analyses, the most commonly assessed subgroup differences were across gender or sex (145 out of 1365 systematic reviews, 11%), age (36 out of 381 systematic reviews, 9%), SES (90 out of 729 systematic reviews, 12%) and race/ethnicity (35 out of 1104 systematic reviews, 3%). Differences in effects across other factors of PROGRESS‐Plus are described in Table 4 (LMIC, place of residence, occupation, religion, social capital, health conditions). The advantage of this strategy is that subgroup analysis summarises the data available in specific populations. However, these subgroup analyses are limited in their ability to detect differences due to statistical issues (e.g. post‐hoc analyses, probability of finding a false association, lack of data in the primary studies, or lack of reporting stratified data in primary studies) (Bambra 2010). Furthermore, subgroup analyses that were conducted were not reported in sufficient detail to judge their credibility (Table 5).

5. Frequency of subgroup analyses meeting credibility criteria.

| Subgroup criteria | n = 58 (%) |

| 1. clinically important difference? | 2 (3%) |

| 2. statistically significant difference? | 13 (22%) |

| 3. a priori hypothesis | 8 (14%) |

| 4. subgroup analysis is one of small number of hypotheses tested? | 3 (5%) |

| 5. differences suggested by within study comparisons | 2 (3%) |

| 6. difference consistent across studies? | 2 (3%) |

| 7. indirect evidence to support hypothesis? | 5 (9%) |

| 8. Rothwell: test by subgroup‐treatment interaction | 1 (2%) |

| 9. Rothwell: trials stratified by subgroup | 0 |

| 10) Consideration of baseline characteristics; | 0 |

| 11) independence of the subgroup effect (i.e. the subgroup effect is not confounded by association with another factor | 0 |

| 12) a priori specification of the direction of effect | 2 (3%) |

| 13) consistency across related outcomes | 1 (2%) |

2) Descriptive assessment of primary studies included in the systematic reviews

2a) Methodology study to assess whether populations in primary studies are described according to PROGRESS‐Plus

Fifty methodology studies (32%) retrieved and evaluated primary studies of included systematic reviews to assess whether data were available from primary studies to conduct subgroup analyses in systematic reviews. Population characteristics were reported in primary studies for sex most frequently (883 out of 1369 studies, 64%), followed by SES (24%), place of residence (18%), education (15%), race/ethnicity (11%),occupation (9%) and social capital (6%). This strategy has the advantage of assessing whether data are available in primary studies, thus assessing whether there is a risk of bias that PROGRESS‐Plus characteristics are under‐reported in systematic reviews (Bambra 2010; Tugwell 2008). However, this strategy does not assess effects on health inequalities, and data may not be available from the primary studies stratified by PROGRESS‐Plus characteristics.

2b) Methodology study to assess whether subgroup analyses conducted in primary studies

Twenty‐eight of the methodology studies of systematic reviews (18%) assessed whether data were available from the primary studies on population characteristics across PROGRESS‐Plus and whether outcomes were analysed using subgroup analysis or another method in the primary studies. In the included primary studies, outcomes were reported separately for sex most commonly (13% of primary studies), followed by age (6%), SES, place of residence, race/ethnicity/culture/language, and education (2% each). Advantages of this approach are that more details are available regarding the methods of subgroup analyses by assessing information in the primary studies than in systematic reviews. Disadvantages of this approach are that it is time‐consuming to locate and assess all primary studies (Bambra 2010; Ogilvie 2004b).

3) Analytic approaches

3a) Methodology study to assess association of PROGRESS‐Plus factors with size of effect

Nine methodology studies (6%) used a method to assess the association of PROGRESS‐Plus factors with the size of effect. Regression analysis was used by one methodology study of systematic reviews on interventions to improve adherence (Morrison 2004). Data were available for age (8 out of 12 systematic reviews), sex (7 out of 12 systematic reviews) and SES (5 out of 12 systematic reviews). One study categorised the effect of gender on outcomes as positive effect, negative effect or no effect (Sherr 2009). Two studies used the harvest plot to assess positive, negative or no gradient in effects across SES, gender and education (Humphreys 2013, Nittas 2020). Five other studies used regression or meta‐regression to assess relationship of one or more PROGRESS factors with the size of effect (Questa 2020, Richardson 2015, Matjasko 2012, Thomson 2018Thomson 2019). Advantages of assessing association of PROGRESS‐Plus factors with size of effect are that it could be used to understand whether some populations do not benefit from or are harmed by interventions and whether there are gradients or dose‐response differences (e.g. across SES). The disadvantage of this approach is that data may be unavailable (e.g. in Morrison 2004, one third of systematic reviews lacked data to conduct this analysis) and missing data may bias the findings. While these approaches were applied at the level of systematic reviews in these methodology studies, they could equally be applied at the level of an individual systematic review, for example harvest plots are a tool developed for systematic reviews (Ogilvie 2008).

3b) Methodology study to compare effect size using an odds ratio, relative risk or risk difference between two groups across PROGRESS‐Plus (e.g. men versus women)

This analysis corresponds to the relative difference approach in Table 1 where the effect size is assessed in two population groups then the relative difference in size of effect is compared using a difference in mean effects or a relative risk or odds ratio. None of the 158 methodology studies reported this analysis.

3c) Methodology studies to assess effects of interventions targeted at a specific population which is disadvantaged (e.g. older people with depression, youth with disabilities)

One hundred and eight methodology studies (68%) searched for systematic reviews of the effects of interventions targeted at populations which were described by the authors as disadvantaged by unequal opportunities for optimal health or high‐quality health care. The focus of these focused methodology studies was most frequently health conditions associated with stigma, discrimination or limited opportunities for health (e.g. HIV, obesity, disability, multiple long‐term conditions); these were assessed as the focus of 19 methodology studies. The next most common focus was place of residence (16 studies), then relationships or environments (six studies) and gender or sex (four studies). Of note, 35 of these methodology studies focused on populations experiencing inequities across more than one PROGRESS‐Plus factor (e.g. children with disability).

The advantage of evaluating interventions focused on specific groups of people is that evidence on effectiveness can be directly used to inform decisions about interventions aimed at specific disadvantaged populations (e.g. older people with depression) (Adamek 2008), and to identify gaps in the evidence‐base. However, this approach may not be possible for some disadvantaged groups where systematic reviews or primary trials have not been conducted. Furthermore, this approach is limited by the methodological quality of the systematic reviews and whether sufficient details about the process of implementation are reported to replicate the interventions. Also, the gap or gradient between these disadvantaged populations and others is not assessed, so the extent to which interventions generate health inequalities is not assessable (Adams 2005).

4) Judgment of applicability to disadvantaged populations or settings

4a) Methodology studies to assess applicability to different populations across PROGRESS‐Plus

Seventeen methodology studies (11%) assessed the applicability and relevance of systematic reviews to improve health of people who experience inequity; eight of these focused on applicability to LMIC settings (Althabe 2008; Bhutta 2009; Chopra 2008; Darmstadt 2009; Lewin 2008; Menezes 2009; Yakoob 2009). Two methodology studies (Althabe 2008, Chopra 2008) used the SUPPORT Collaboration checklists for equity, applicability and scaling up to make judgments about whether the results from systematic reviews could be transferred to LMIC settings and could be expected to confer health benefits (details of SUPPORT checklists available in Appendix 4, and at: http://www.support‐collaboration.org/summaries/methods.htm). Four studies (Yakoob 2009, Darmstadt 2009, Menezes 2009, Bhutta 2009) used the SIGN tools to assess quality and strength of the evidence, including the directness of evidence to LMIC settings (see Appendix 5 and Appendix 6 for details about how applicability and generalisability are assessed using considered judgment). One study used absolute risk to extrapolate the impact in low‐resource settings (Shannon 2014). Two studies appraised feasibility and relevance to LMIC (Pantoja 2017, Haws 2009). The PRISMA‐Equity 2012 reporting guideline provided an example of judging applicability to LMIC settings (Welch 2012). Four studies used the GRADE tools to assess quality of evidence for each outcome. The GRADE assessment also includes an assessment of directness of evidence to the population of interest, which was people in LMIC in three studies (Lewin 2008, Bhutta 2008, Barros 2010) and preventing obesity in adolescents in one methodology study (Flodgren 2020). These studies do not report how this judgment was made, or when the difference between people in the trials included in the systematic reviews would be large enough to downgrade the quality of evidence for indirectness. Two studies used criteria of biological plausibility and feasibility of implementation in LMIC to select interventions. These criteria were judged by a panel of experts using Delphi consensus methods (Jones 2003, Darmstadt 2005). These authors do not report how these judgments were made, nor whether there was discrepancy in opinion in making these judgments. One study reported the use of programme theory or logic models to assess applicability to specific populations, and found that 29 out of 37 systematic reviews on health inequities used programme theory in some way (Maden 2017). Studies which assessed applicability described difficulty in making judgments about applicability of interventions in different settings than the settings where the primary studies were conducted (for example, Althabe 2008 describes difficulty in assessing applicability because the context and setting is different in Argentina than in other low‐ and middle‐income countries). For judging the relevance and applicability to LMIC, there was limited evidence on real‐world effectiveness in LMIC, thus the authors relied on efficacy data from systematic reviews as well as expert opinion (Darmstadt 2005). For example, some interventions require access to highly‐skilled professionals, equipment or emergency transportation which may not be available in LMIC (Darmstadt 2009). For example, smoking cessation trials have almost all been conducted in high‐income countries, and their applicability to low‐ and middle‐income country settings is questioned because risk factors may be different for women in LMIC (Yakoob 2009).

Advantages of judging applicability to disadvantaged populations and/or settings are that it makes use of the best available evidence to make judgments that can be used to inform policies. Disadvantages are that the judgment of applicability and equity are extremely challenging and requires content expertise, knowledge of LMIC settings and methodological knowledge (Althabe 2008). Furthermore, assessing applicability does not assess the likely magnitude of effects and, since LMIC settings are extremely heterogeneous, the judgments required for these checklists need to be framed for specific settings.

5) Stakeholder engagement in methodology studies and systematic reviews to assess health equity questions